Abstract

The damage control concept is an essential component in the management of severely injured patients. The principles in sequence are as follows: (1) abbreviated surgical procedures limited to haemorrhage and contamination control; (2) correction of physiological derangements; (3) definitive surgical procedures. Although originally described in the management of major abdominal injuries, the concept has been extended to include thoracic, vascular, orthopedic, and neurosurgical procedures, as well as anesthesia and resuscitative strategies.

Keywords: Damage control, management, principles, surgery, trauma

INTRODUCTION

“Damage control” has become an essential component of modern trauma care. This fundamental concept has a military origin. The United States Navy considers proficiency in basic damage control skills as part of basic seamanship. The stated objectives of shipboard damage control are as follows:

Take all practicable preliminary measures to prevent damage

Minimize and localize damage as it occurs

Accomplish emergency repairs as quickly as possible, restore equipment to operation, and care for the injured personnel.[1]

These objectives and the overriding principle of performing the minimum repairs necessary to maintain ship worthiness have been adapted to the care of severely injured patients. The most pervasive concept in trauma care over the last 2 decades has been the adoption of damage control principles.[2]

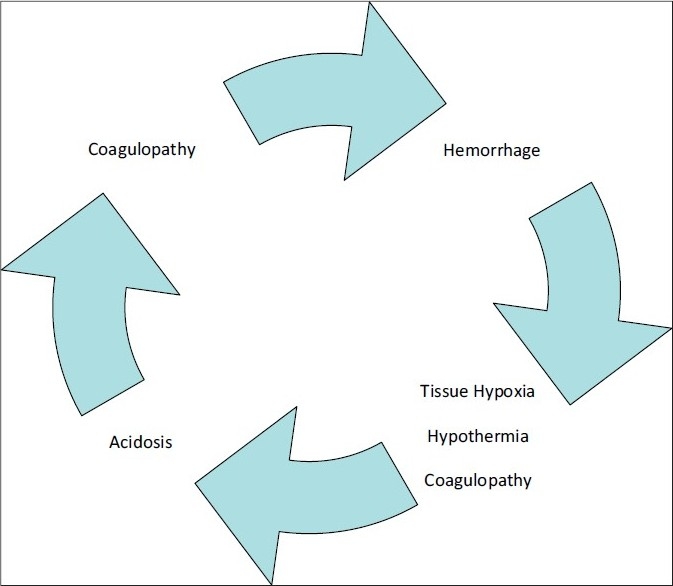

Damage control is a fundamental shift from the traditional surgical focus of anatomical restoration to that of physiological restoration. Pringle perhaps ushered the damage control concept by advocating temporary inflow occlusion and perihepatic packing for liver hemorrhage in 1908.[3] In 1982, Kashuk et al.[4] described the development of the “vicious cycle” of hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis in major abdominal vascular injuries [Figure 1]. Stone et al. described truncating the operative procedure at the first indication of major coagulopathy in the following year.[5] As originally described, the damage control concept consists of 3 separate components.[2] Initially, the patient undergoes resuscitative, abbreviated surgery, where control of hemorrhage and contamination is rapidly obtained and definitive repairs deferred. The patient is then transported to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) where active rewarming, correction of coagulopathy and acidosis occurs. Once normal physiology is restored, definitive surgical management is completed.

Figure 1.

The “Vicious Cycle” from Kashuk et al.[4]

THE LETHAL TRIAD

Independently, hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis have been demonstrated to worsen the outcome of severely injured patients. If not corrected, each component can further perpetuate the vicious cycle, resulting in certain death.

Hypothermia results as an imbalance between heat loss and the body's ability to generate and maintain metabolic energy.[6] Clinically significant hypothermia occurs when the core temperature is <35ºC[7] ; 21% of all severely injured patients and up to 46% of all trauma patients requiring laparotomy are hypothermic.[8,9] In 1987, Jurkovich et al. demonstrated a 100% mortality in those severely injured patients undergoing laparotomy, who had a core temperature of <32ºC.[10] Hypothermia is associated with an increase in sympathetic drive with resulting peripheral vasoconstriction, end-organ hypoperfusion, and metabolic acidosis from anaerobic respiration.[11] In addition, hypothermia may exacerbate coagulopathy by causing dysfunction of the intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways,[12] as well as platelet activity.[13,14]

Coagulopathy occurs due to a variety of mechanisms. Traditionally, the causes of coagulopathy in severely injured patients have been attributed to acidosis, hypothermia, consumption of clotting factors, and hemodilution. However, this theory has been challenged by recent data suggesting that acute coagulopathy in trauma is due to hypoperfusion rather than the aforementioned causes.[15–17] Brohi and colleagues have suggested that hypoperfusion leads to activation of protein C and systemic hyperfibrinolysis.[18,19]

Acidosis is a result of tissue hypoperfusion and subsequent switch from aerobic to anaerobic respiration. The adverse effects of acidosis on cardiac function were documented in physiological studies over 40 years ago.[20,21] In addition, impairment of oxygen utilization and coagulation dysfunction are associated with the acidotic state.[22–24]

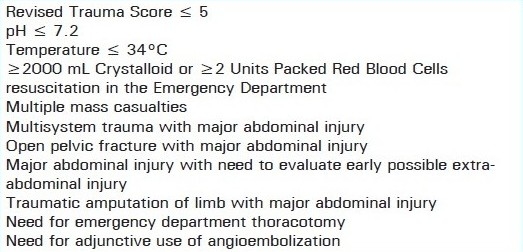

IDENTIFYING THE “DAMAGE CONTROL” PATIENT

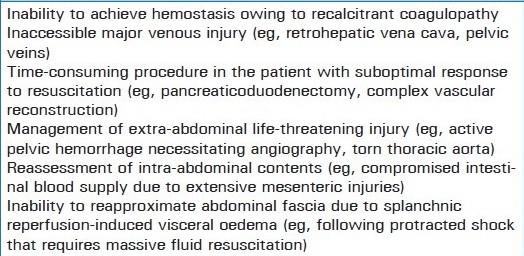

The damage control approach is only suitable for select group of patients. In Rotondo et al's original series, only patients with major vascular injury and 2 or more visceral injuries showed a survival benefit with a damage control approach.[2] Thus, only those with a severe injury pattern, whose physiologic reserve is insufficient to tolerate a prolonged, definitive operative procedure, should be subjected to a damage control approach. Asensio et al.[25] identified pre-operating room characteristics predictive of “exsanguinating syndrome,” in which a damage control approach would be appropriate [Box 1]. There is a 98% probability of developing life-threatening coagulopathy if the Injury Severity Score is >25, systolic blood pressure < 70 mmHg, pH < 7.1, and temperature < 34ºC.[26] Moore et al.[26] outlined indications for abbreviating the laparotomy [Box 2]. If the physiological boundaries have been breached, operative interventions must be abbreviated. Hirshberg and Mattox[27] furthermore recommend that “injury pattern recognition” guide the experienced surgeon toward an abbreviated operation.

Box 1.

Preoperative indications for damage control from Asensio et al.[25]

Box 2.

Indications for abbreviated celiotomy from Moore et al.[26]

Although originally described for those patients requiring abdominal operative interventions, the same criteria for damage control apply for other body regions. Damage control principles have been described for thoracic, vascular, neurosurgical, and orthopedic injuries, as well as trauma anesthesia.[28–41] For example, in orthopedic procedures, severe associated head injury and/or pulmonary contusion have been suggested as indications for damage control surgery.[42–44]

DAMAGE CONTROL SEQUENCE AND INTERVENTIONS

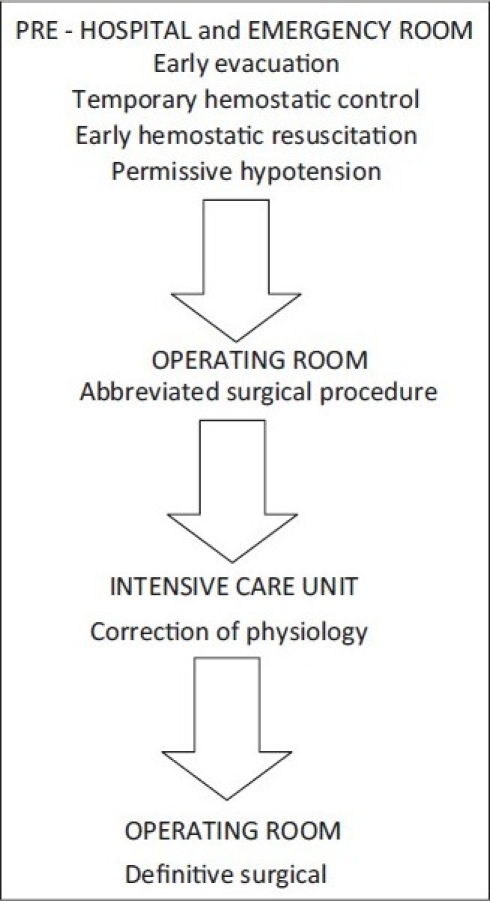

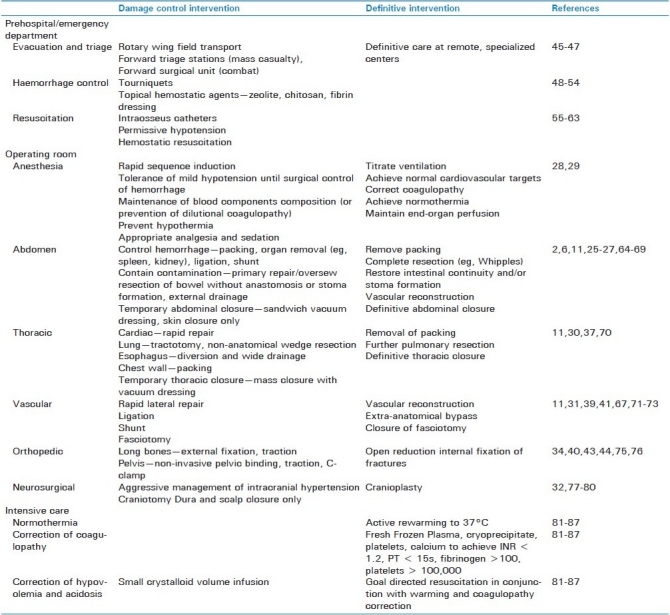

Damage control principles are applicable in all initial phases of care of the severely injured patient [Figure 2]. Temporary and definitive interventions at each phase are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Damage control sequence

Table 1.

Summary of damage control and defi nitive interventions

Prehospital and Emergency Department damage control interventions are aimed toward temporarily stopping hemorrhage and maintaining minimum perfusion until definitive hemorrhage control can be achieved. Rapid transport of the patient from the scene to early surgical care has enabled the survival of many injured patients, who previously had a significant risk of dying in the prehospital phase. Many advancements in prehospital transport have been made during military conflicts. The injury to admission interval was reduced from 12-18 h in World War II to 1.2–5 h for the Vietnam war, with a corresponding decrease in mortality from 9.5% to 2.3%. This was in part due to the improved aeromedical evacuation of injured soldiers.[45,46] The US Army has adopted a staged approach to battlefield treatment, where damage control principles are practiced by Forward Surgical Teams and/or at the Combat Support Hospital.[47]

Most prehospital temporary hemostatic maneuvers also have a military origin. Tourniquet use has been demonstrated to be effective and life-saving during recent military conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.[48–51] Tourniquets must be applied correctly, as inappropriately applied devices cause an increase in bleeding due to occlusion of low-pressure venous outflow and inadequate occlusion of arterial inflow.[52]

Topical hemostatic agents for external bleeding include dry fibrin sealant dressings, chitosan dressings, and mineral zeolite. These agents have been used again in military conflicts with success for mainly large soft tissue injuries with small vessel bleeding.[53,54]

The concept of “permissive hypotension” was originally noted by Cannon et al. [55] and subsequently shown by Bickell et al.[56] to be beneficial in patients with penetrating injuries to the torso. Early hemostatic resuscitation has also been described as “damage control resuscitation.” The concept behind this strategy is that early replacement of blood, plasma, and platelets will prevent spiralling into the vicious cycle due to excessive infusion of crystalloid solution. The military experience in Iraq indicated a physiological improvement in those injured soldiers resuscitated with a 1:1:1 ratio of Packed Red Blood Cells toFresh Frozen Plasma and Platelets, respectively.[57–60] Emerging data suggest that this strategy may likewise improve survival in severely injured civilian trauma patients,[61–63] but awaits confirmation in prospective trials.

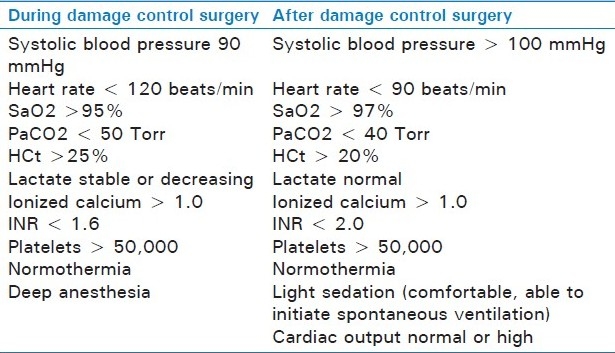

Within the operating room, damage control concepts apply to both anesthesia and surgery. Damage control anesthesia aims to rapidly establish a definitive airway, maintain oxygenation, prevent hypothermia, initiate correction of coagulopathy, and maintain permissive hypotension until definitive hemorrhage control has been obtained[28,29] [Table 2].

Table 2.

Anesthetic resuscitation goals during and after damage control surgery (from Dutton et al.[29])

Abdominal damage control entails rapid celiotomy, control of hemorrhage, limiting contamination, and temporary abdominal closure.[2,6,11] Surgical bleeding may be controlled by a combination of packing, direct arterial ligation, vascular clamping in situ, splenectomy, and nephrectomy, whereas contamination is limited by rapid stapled resections, temporary hollow viscus closures and pancreatic drainage.[2,11,25–27,64–67] Temporary abdominal closure is most commonly achieved with a vacuum-assisted dressing.[68,69] Alternative methods of temporary closure include towel clip or running nylon skin closure, Bogota bag, or silo closure. Removal of packs, thorough re-exploration, complete vascular repair, establishment of gastrointestinal continuity or stoma formation, and fascial closure are carried out in the definitive phase.[25,27]

Thoracic injuries present a unique challenge, as structures within the chest are not easily controlled with temporary maneuvers. Rapid and definitive control of hemorrhage and air leaks is required. Packing is limited to the apices and cardiophrenic angles, but lung injuries can be rapidly controlled with nonanatomic, stapled wedge resections.[30] Pulmonary tractotomy can achieve rapid hemorrhage control in penetrating lung injury.[37,70] Esophageal injuries are best treated by diversion and wide drainage.[30] Temporary closure can be achieved by simple mass closure or vacuum-assisted dressings.[11,30] Definitive procedures at re-operation include removal of packs, thorough exploration for air leaks, and chest wall closure.

Damage control principles for vascular trauma hinges on 2 categories of vascular repairs: simple and complex.[31] Complex repairs include vascular reconstructions, such as patch angioplasty, –end anastomosis and graft interposition, which are time consuming and not ideal in the hypothermic, coagulopathic patient. Simple techniques include lateral repair, ligation,[71] and temporary shunt.[39,41,67,72,73] Fasciotomy is advisable to prevent compartment syndrome.[31,74] Once appropriate physiology has been restored, definitive vascular reconstruction can be achieved before delayed closure of fasciotomy wounds.[11,31]

Since the 1980s, “early total care” has been the standard of care for orthopedic injuries following Bone's landmark paper[75] demonstrating an increase in pulmonary complications with delayed femoral fracture repair. However, an increasing understanding of the inflammatory process and effects of orthopedic intervention, otherwise known as the “second hit,” led to the concept of damage control orthopedics.[43,44] Temporary external fixation or traction for long-bone fractures and minimally invasive pelvic stabilization for pelvic fractures are the initial orthopedic interventions.[34,40] Definitive open reduction internal fixation should take place after resuscitation. Some data suggest that definitive fixation should occur within 24 h of injury or after 5 days to avoid pulmonary complications.[76]

The critical component of head injury management is prevention of secondary brain injury.[77,78] Optimizing the general condition of the patient is essential in optimizing outcomes from head injury. Damage control neurosurgery involves rapid arrest of intracranial bleeding, the evacuation of intracranial hematomas and the early debridement of compound wounds to the skull.[32] Craniectomy may be beneficial for cerebral edema, however, dural closure should be attempted to prevent intracranial infection. The extent of debridement, however, remains a controversial issue, as aggressive debridement of brain tissue, bone and missile fragments, may at times worsen neurologic deficits.[79,80] Bone defects are repaired once the brain swelling subsides.

After the initial damage control surgery, secondary resuscitation takes place in the ICU. The aims as previously stated are to rewarm the patient and correct acidosis and coagulopathy. Rewarming to a temperature of 37°C can be achieved by warming the ICU room, removing any wet sheets or clothing, covering the patient with warm blankets and applying a forced air-warming device.[81,82] Intravenous fluid warmers have improved the resuscitation of major trauma patients.[83,84] Extracorporeal warming techniques are sometimes required for profound hypothermia.[85] Initial coagulation targets should include INR < 1.2, fibrinogen >100 mg/dL, platelets > 100,000/mm3.[81,82] In addition, Vitamin K and calcium should also be administered. Although activated factor VII was a promising adjunct in the arrest of nonsurgical sources of hemorrhage, recent trials failed to show a mortality benefit.[86,87] Acidosis is usually corrected once the patient is adequately warmed and resuscitated. Hemodynamic and invasive monitoring can aid goal-directed resuscitation.[81,82]

OUTCOMES AND COMPLICATIONS FROM DAMAGE CONTROL SURGERY

A review by Rotondo et al.[88] identified an overall 50% mortality and 40% morbidity in 961 damage control patients. The early reports of damage control surgery demonstrated a significant improvement in mortality when comparing patients undergoing abbreviated procedures to those patients undergoing conventional surgery.[2,5] More recent series have confirmed a survival benefit with the damage control approach.[89,90] It is important to note that these comparisons apply to damage control laparotomy; mortality outcomes have not yet been demonstrated in other damage control procedures.

Complications from damage control laparotomy include intra-abdominal abscess formation (0%–83%), enteric fistula (2%–25%), dehiscence (9%–25%), abdominal compartment syndrome (2%–25%), and inability to reapproximate the fascia edges (10–40%).[2,5,26,27,64,66,68,69,89,91,92] Orthopedic external fixation may increase pin-site infection and damage control vascular procedures may increase graft infections.[31,34]

CONCLUSION

It is essential that trauma providers be au-fait with the principles of damage control for they are clearly life-saving in many patients with multisystem trauma. The damage control concept originated over 100 years ago, and has since grown to encompass all phases of the initial care of the severely injured patient. By learning from the accumulated experience, outcomes and complications of damage control, modern surgeons can apply this strategy following a rationalized approach.[93] Nowadays, damage control principles are also applied for non-trauma care, including the treatment of abdominal compartment syndrome and intra-abdominal sepsis.[94,95] Ongoing and future developments will continue to define the most appropriate patients that may benefit from damage control.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Navy US. Surface Ship Survivability. United States: Naval War Publications; 1996. pp. 3–20.31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotondo MF, Schwab CW, McGonigal MD, Phillips GR, 3rd, Fruchterman TM, Kauder DR, et al. ‘Damage control’: An approach for improved survival in exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J Trauma. 1993;35:375–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pringle JH. Notes on the arrest of hepatic hemorrhage due to trauma. Ann Surg. 1908;48:541–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-190810000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kashuk JL, Moore EE, Millikan JS, Moore JB. Major abdominal vascular trauma--a unified approach. J Trauma. 1982;22:672–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone HH, Strom PR, Mullins RJ. Management of the major coagulopathy with onset during laparotomy. Ann Surg. 1983;197:532–5. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198305000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro MB, Jenkins DH, Schwab CW, Rotondo MF. Damage control: Collective review. J Trauma. 2000;49:969–78. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200011000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luna GK, Maier RV, Pavlin EG, Anardi D, Copass MK, Oreskovich MR. Incidence and effect of hypothermia in seriously injured patients. J Trauma. 1987;27:1014–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198709000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregory JS, Flancbaum L, Townsend MC, Cloutier CT, Jonasson O. Incidence and timing of hypothermia in trauma patients undergoing operations. J Trauma. 1991;31:795–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199106000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinemann S, Shackford SR, Davis JW. Implications of admission hypothermia in trauma patients. J Trauma. 1990;30:200–2. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jurkovich GJ, Greiser WB, Luterman A, Curreri PW. Hypothermia in trauma victims: An ominous predictor of survival. J Trauma. 1987;27:1019–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loveland JA, Boffard KD. Damage control in the abdomen and beyond. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1095–101. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gubler KD, Gentilello LM, Hassantash SA, Maier RV. The impact of hypothermia on dilutional coagulopathy. J Trauma. 1994;36:847–51. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199406000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrara A, MacArthur JD, Wright HK, Modlin IM, McMillen MA. Hypothermia and acidosis worsen coagulopathy in the patient requiring massive transfusion. Am J Surg. 1990;160:515–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valeri CR, Feingold H, Cassidy G, Ragno G, Khuri S, Altschule MD. Hypothermia-induced reversible platelet dysfunction. Ann Surg. 1987;205:175–81. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198702000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Davenport RA. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: Mechanism, identification and effect. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13:680–5. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f1e78f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacLeod JB, Lynn M, McKenney MG, Cohn SM, Murtha M. Early coagulopathy predicts mortality in trauma. J Trauma. 2003;55:39–44. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000075338.21177.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maegele M, Lefering R, Yucel N, Tjardes T, Rixen D, Paffrath T, et al. Early coagulopathy in multiple injury: An analysis from the German Trauma Registry on 8724 patients. Injury. 2007;38:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, Matthay MA, Mackersie RC, Pittet JF. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: Initiated by hypoperfusion: Modulated through the protein C pathway? Ann Surg. 2007;245:812–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000256862.79374.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, Schultz MJ, Levi M, Mackersie RC, et al. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: Hypoperfusion induces systemic anticoagulation and hyperfibrinolysis. J Trauma. 2008;64:1211–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318169cd3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downing SE, Talner NS, Gardner TH. Influences of hypoxemia and acidemia on left ventricular function. Am J Physiol. 1966;210:1327–34. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.210.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wildenthal K, Mierzwiak DS, Myers RW, Mitchell JH. Effects of acute lactic acidosis on left ventricular performance. Am J Physiol. 1968;214:1352–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1968.214.6.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn EL, Moore EE, Breslich DJ, Galloway WB. Acidosis-induced coagulopathy. Surg Forum. 1979;30:471–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manger WM, Nahas GG, Hassam D, Habif DV, Papper EM. Effect of pH control and increased O2 delivery on the course of hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg. 1962;156:503–10. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196209000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore EE, Dunn EL, Breslich DJ, Galloway WB. Platelet abnormalities associated with massive autotransfusion. J Trauma. 1980;20:1052–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198012000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asensio JA, McDuffie L, Petrone P, Roldań G, Forno W, Gambaro E, et al. Reliable variables in the exsanguinated patient which indicate damage control and predict outcome. Am J Surg. 2001;182:743–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00809-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore EE, Burch JM, Franciose RJ, Offner PJ, Biffl WL. Staged physiologic restoration and damage control surgery. World J Surg. 1998;22:1184–90. doi: 10.1007/s002689900542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirshberg A, Wall MJ, Jr, Mattox KL. Planned reoperation for trauma: A two year experience with 124 consecutive patients. J Trauma. 1994;37:365–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ham AA, Coveler LA. Anesthetic considerations in damage control surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:909–20. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70593-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dutton R. Damage control anesthesia. TraumaCare. 2005;15:197–201. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wall MJ, Jr, Soltero E. Damage control for thoracic injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:863–78. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aucar JA, Hirshberg A. Damage control for vascular injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:853–62. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70589-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenfeld JV. Damage control neurosurgery. Injury. 2004;35:655–60. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giannoudis PV, Pape HC. Damage control orthopaedics in unstable pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 2004;35:671–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts CS, Pape HC, Jones AL, Malkani AL, Rodriguez JL, Giannoudis PV. Damage control orthopaedics: Evolving concepts in the treatment of patients who have sustained orthopaedic trauma. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:447–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rotondo MF, Bard MR. Damage control surgery for thoracic injuries. Injury. 2004;35:649–54. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hildebrand F, Giannoudis P, Kretteck C, Pape HC. Damage control: Extremities. Injury. 2004;35:678–89. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wall MJ, Jr, Villavicencio RT, Miller CC, 3rd, Aucar JA, Granchi TA, Liscum KR, et al. Pulmonary tractotomy as an abbreviated thoracotomy technique. J Trauma. 1998;45:1015–23. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199812000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grotz MR, Gummerson NW, Gänsslen A, Petrowsky H, Keel M, Allami MK, et al. Staged management and outcome of combined pelvic and liver trauma.An international experience of the deadly duo. Injury. 2006;37:642–51. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scalea TM, Mann R, Austin R, Hirschowitz M. Staged procedures for exsanguinating lower extremity trauma: An extension of a technique--case report. J Trauma. 1994;36:291–3. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199402000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pape HC, Tornetta P, 3rd, Tarkin I, Tzioupis C, Sabeson V, Olson SA. Timing of fracture fixation in multitrauma patients: The role of early total care and damage control surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:541–9. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ball CG, Feliciano DV. Damage control techniques for common and external iliac artery injuries: Have temporary intravascular shunts replaced the need for ligation? J Trauma. 2010;68:1117–20. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d865c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaicks RR, Cohn SM, Moller BA. Early fracture fixation may be deleterious after head injury. J Trauma. 1997;42:1–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pape HC, Auf‘m’Kolk M, Paffrath T, Regel G, Sturm JA, Tscherne H. Primary intramedullary femur fixation in multiple trauma patients with associated lung contusion--a cause of posttraumatic ARDS? J Trauma. 1993;34:540–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199304000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pape HC, Hildebrand F, Pertschy S, Zelle B, Garapati R, Grimme K, et al. Changes in the management of femoral shaft fractures in polytrauma patients: From early total care to damage control orthopedic surgery. J Trauma. 2002;53:452–61. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCaughey BG, Garrick J, Carey LC, Kelley JB. Naval Support Activity Hospital, Danang, Combat casualty study. Mil Med. 1988;153:109–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNamara JJ, Stremple JF. Causes of death following combat injury in an evacuation hospital in Vietnam. J Trauma. 1972;12:1010–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blackbourne LH. Combat damage control surgery. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S304–10. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817e2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kragh JF, Jr, Littrel ML, Jones JA, Walters TJ, Baer DG, Wade CE, et al. Battle Casualty Survival with Emergency Tourniquet Use to Stop Limb Bleeding 2009. J Emerg Med. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.07.022. [In press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kragh JF, Jr, Walters TJ, Baer DG, Fox CJ, Wade CE, Salinas J, et al. Practical use of emergency tourniquets to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. J Trauma. 2008;64:S38–49. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31816086b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kragh JF, Jr, Walters TJ, Baer DG, Fox CJ, Wade CE, Salinas J, et al. Survival with emergency tourniquet use to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. Ann Surg. 2009;249:1–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818842ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lakstein D, Blumenfeld A, Sokolov T, Lin G, Bssorai R, Lynn M, et al. Tourniquets for hemorrhage control on the battlefield: A 4-year accumulated experience. J Trauma. 2003;54:S221–5. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000047227.33395.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Starnes BW, Beekley AC, Sebesta JA, Andersen CA, Rush RM., Jr Extremity vascular injuries on the battlefield: Tips for surgeons deploying to war. J Trauma. 2006;60:432–42. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197628.55757.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Achneck HE, Sileshi B, Jamiolkowski RM, Albala DM, Shapiro ML, Lawson JH. A comprehensive review of topical hemostatic agents: Efficacy and recommendations for use. Ann Surg. 2010;251:217–28. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c3bcca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cox ED, Schreiber MA, McManus J, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. New hemostatic agents in the combat setting. Transfusion. 2009;49:248S–55S. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cannon W, Fraser J, Cowell E. The preventative treatment of wound shock. JAMA. 1918;70:618. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bickell WH, Wall MJ, Jr, Pepe PE, Martin RR, Ginger VF, Allen MK, et al. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1105–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410273311701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fox CJ, Gillespie DL, Cox ED, Kragh JF, Jr, Mehta SG, Salinas J, et al. Damage control resuscitation for vascular surgery in a combat support hospital. J Trauma. 2008;65:1–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318176c533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fox CJ, Gillespie DL, Cox ED, Mehta SG, Kragh JF, Jr, Salinas J, et al. The effectiveness of a damage control resuscitation strategy for vascular injury in a combat support hospital: Results of a case control study. J Trauma. 2008;64:S99–106. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181608c4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holcomb JB. Damage control resuscitation. J Trauma. 2007;62:S36–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3180654134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holcomb JB, Jenkins D, Rhee P, Johannigman J, Mahoney P, Mehta S, et al. Damage control resuscitation: Directly addressing the early coagulopathy of trauma. J Trauma. 2007;62:307–10. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3180324124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duchesne JC, Islam TM, Stuke L, Timmer JR, Barbeau JM, Marr AB, et al. Hemostatic resuscitation during surgery improves survival in patients with traumatic-induced coagulopathy. J Trauma. 2009;67:33–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819adb8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duchesne JC, Kimonis K, Marr AB, Rennie KV, Wahl G, Wells JE, et al. Damage control resuscitation in combination with damage control laparotomy: A survival advantage. J Trauma. 2010;69:46–52. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181df91fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holcomb JB, Wade CE, Michalek JE, Chisholm GB, Zarzabal LA, Schreiber MA, et al. Increased plasma and platelet to red blood cell ratios improves outcome in 466 massively transfused civilian trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2008;248:447–58. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185a9ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burch JM, Ortiz VB, Richardson RJ, Martin RR, Mattox KL, Jordan GL., Jr Abbreviated laparotomy and planned reoperation for critically injured patients. Ann Surg. 1992;215:476–83. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199205000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carrillo EH, Bergamini TM, Miller FB, Richardson JD. Abdominal vascular injuries. J Trauma. 1997;43:164–71. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199707000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, Burch JM, Bitondo CG, Jordan GL., Jr Packing for control of hepatic hemorrhage. J Trauma. 1986;26:738–43. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198608000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reilly PM, Rotondo MF, Carpenter JP, Sherr SA, Schwab CW. Temporary vascular continuity during damage control: Intraluminal shunting for proximal superior mesenteric artery injury. J Trauma. 1995;39:757–60. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199510000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barker DE, Green JM, Maxwell RA, Smith PW, Mejia VA, Dart BW, et al. Experience with vacuum-pack temporary abdominal wound closure in 258 trauma and general and vascular surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:784–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garner GB, Ware DN, Cocanour CS, Duke JH, McKinley BA, Kozar RA, et al. Vacuum-assisted wound closure provides early fascial reapproximation in trauma patients with open abdomens. Am J Surg. 2001;182:630–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00786-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Asensio JA, Demetriades D, Berne JD, Velmahos G, Cornwell EE, 3rd, Murray J, et al. Stapled pulmonary tractotomy: A rapid way to control hemorrhage in penetrating pulmonary injuries. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:486–7. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pourmoghadam KK, Fogler RJ, Shaftan GW. Ligation: An alternative for control of exsanguination in major vascular injuries. J Trauma. 1997;43:126–30. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199707000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eger M, Golcman L, Goldstein A, Hirsch M. The use of a temporary shunt in the management of arterial vascular injuries. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1971;132:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sriussadaporn S, Pak-art R. Temporary intravascular shunt in complex extremity vascular injuries. J Trauma. 2002;52:1129–33. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200206000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jacob JE. Compartment syndrome. A potential cause of amputation in battlefield vascular injuries. Int Surg. 1974;59:542–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bone LB, Johnson KD, Weigelt J, Scheinberg R. Early versus delayed stabilization of femoral fractures. A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:336–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brundage SI, McGhan R, Jurkovich GJ, Mack CD, Maier RV. Timing of femur fracture fixation: Effect on outcome in patients with thoracic and head injuries. J Trauma. 2002;52:299–307. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200202000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dan NG, Berry G, Kwok B, Mandryk JA, Ring IT, Sewell MF, et al. Experience with extradural haematomas in New South Wales. Aust N Z J Surg. 1986;56:535–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1986.tb07096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stening WA, Berry G, Dan NG, Kwok B, Mandryk JA, Ring I, et al. Experience with acute subdural haematomas in New South Wales. Aust N Z J Surg. 1986;56:549–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1986.tb07098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brandvold B, Levi L, Feinsod M, George ED. Penetrating craniocerebral injuries in the Israeli involvement in the Lebanese conflict, 1982-1985. Analysis of a less aggressive surgical approach. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:15–21. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.1.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Taha JM, Saba MI, Brown JA. Missile injuries to the brain treated by simple wound closure: Results of a protocol during the Lebanese conflict. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:380–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Parr MJ, Alabdi T. Damage control surgery and intensive care. Injury. 2004;35:713–22. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sagraves SG, Toschlog EA, Rotondo MF. Damage control surgery--the intensivist's role. J Intensive Care Med. 2006;21:5–16. doi: 10.1177/0885066605282790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Booke M, Sielenkämper A. [Massive transfusion with the rapid infusion system. Its effect on core body temperature] Anaesthesist. 2001;50:926–9. doi: 10.1007/s00101-001-0244-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dunham CM, Belzberg H, Lyles R, Weireter L, Skurdal D, Sullivan G, et al. The rapid infusion system: A superior method for the resuscitation of hypovolemic trauma patients. Resuscitation. 1991;21:207–27. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(91)90047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gentilello LM, Cobean RA, Offner PJ, Soderberg RW, Jurkovich GJ. Continuous arteriovenous rewarming: Rapid reversal of hypothermia in critically ill patients. J Trauma. 1992;32:316–25. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Boffard KD, Riou B, Warren B, Choong PI, Rizoli S, Rossaint R, et al. Recombinant factor VIIa as adjunctive therapy for bleeding control in severely injured trauma patients: Two parallel randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials. J Trauma. 2005;59:8–15. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000171453.37949.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dutton RP, Hess JR, Scalea TM. Recombinant factor VIIa for control of hemorrhage: Early experience in critically ill trauma patients. J Clin Anesth. 2003;15:184–8. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rotondo MF, Zonies DH. The damage control sequence and underlying logic. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:761–77. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70582-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Finlay IG, Edwards TJ, Lambert AW. Damage control laparotomy. Br J Surg. 2004;91:83–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nicholas JM, Rix EP, Easley KA, Feliciano DV, Cava RA, Ingram WL, et al. Changing patterns in the management of penetrating abdominal trauma: The more things change, the more they stay the same. J Trauma. 2003;55:1095–108. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000101067.52018.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abikhaled JA, Granchi TS, Wall MJ, Hirshberg A, Mattox KL. Prolonged abdominal packing for trauma is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Am Surg. 1997;63:1109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ekeh AP, McCarthy MC, Woods RJ, Walusimbi M, Saxe JM, Patterson LA. Delayed closure of ventral abdominal hernias after severe trauma. Am J Surg. 2006;191:391–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Higa G, Friese R, O’Keeffe T, Wynne J, Bowlby P, Ziemba M, et al. Damage control laparotomy: A vital tool once overused. J Trauma. 2010;69:53–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e293b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stawicki SP, Brooks A, Bilski T, Scaff D, Gupta R, Schwab CW, et al. The concept of damage control: Extending the paradigm to emergency general surgery. Injury. 2008;39:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Van Ruler O, Mahler CW, Boer KR, Reuland EA, Gooszen HG, Opmeer BC, et al. Comparison of on-demand vs planned relaparotomy strategy in patients with severe peritonitis: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;298:865–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.8.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]