Abstract

Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium L.) (Asteraceae) is a medicinal plant traditionally used for the treatment of fevers, migraine headaches, rheumatoid arthritis, stomach aches, toothaches, insect bites, infertility, and problems with menstruation and labor during childbirth. The feverfew herb has a long history of use in traditional and folk medicine, especially among Greek and early European herbalists. Feverfew has also been used for psoriasis, allergies, asthma, tinnitus, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. The plant contains a large number of natural products, but the active principles probably include one or more of the sesquiterpene lactones known to be present, including parthenolide. Other potentially active constituents include flavonoid glycosides and pinenes. It has multiple pharmacologic properties, such as anticancer, anti-inflammatory, cardiotonic, antispasmodic, an emmenagogue, and as an enema for worms. In this review, we have explored the various dimensions of the feverfew plant and compiled its vast pharmacologic applications to comprehend and synthesize the subject of its potential image of multipurpose medicinal agent. The plant is widely cultivated to large regions of the world and its importance as a medicinal plant is growing substantially with increasing and stronger reports in support of its multifarious therapeutic uses.

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory, migraine, parthenolide, Tanacetum parthenium

INTRODUCTION

Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium L.) belonging to the family Asteraceae (daisies) is a daisy-like perennial plant found commonly in gardens and along roadsides. The name stems from the Latin word febrifugia, “fever reducer.” The first-century Greek physician Dioscorides prescribed feverfew for “all hot inflammations.” Also known as “featherfew,” because of its feathery leaves.[1–3] It is a short, bushy, aromatic perennial that grows 0.3–1 m in height. Its yellow-green leaves are usually less than 8 cm in length, almost hairless, and pinnate–bipinnate (chrysanthemum-like). Its yellow flowers bloom from July to October, are about 2 cm in diameter. They resemble those of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla), for which they are sometimes confused, and have a single layer of white outer-ray florets.[4–6] This aromatic plant gives off a strong and bitter odor. Its yellow-green leaves are alternate (in other words the leaves grow on both sides of the stem at alternating levels), and turn downward with short hairs. The small, daisy-like yellow flowers are arranged in a dense flat-topped cluster [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium): whole plant (a), flower (b), and feathery leaves (c)

Common name

Chrysanthemum parthenium , Feverfew, featherfew, altamisa, bachelor's button, featherfoil, febrifuge plant, midsummer daisy, nosebleed, Santa Maria, wild chamomile, wild quinine, chamomile grande, chrysanthemum atricaire, federfoy, flirtwort, Leucanthemum parthenium, Matricaria capensis, Matricaria eximia hort, Matricaria parthenium L., MIG-99, mother herb, Parthenium hysterophorus, parthenolide, Pyrenthrum parthenium L, European feverfew, feather-fully, feddygen fenyw, flirtroot, grande chamomile, mutterkraut, and vetter-voo.[1–5]

Botanical classification

Kingdom : Plantae (Plants)

Subkingdom : Trachiobionta (Vascular plants)

Super division : Spermatophyta (Seed plants)

Division : Mangliophyta (Flowering plants)

Class : Magnoliopsida (Dicotyledons)

Subclass : Asteridae

Order : Asterales

Family : Asteraceae (Aster family)

Genus : Tanacetum (tansy)

Species : Tanacetum parthenium (feverfew)

Habitat

Native to the Balkan Peninsula, feverfew is now found in Australia, Europe, China, Japan, and North Africa. In the mid-19th century, feverfew was introduced in the United States. The plant grows along roadsides, fields, waste areas, and along the borders of woods from eastern Canada to Maryland and westward to Missouri.

History

Historically, the plant has been placed into 5 different genera, thus some controversy exists as to which genus the plant belongs. Former botanical names include: Chrysanthemum parthenium (L.) Bernh., Leucanthemum parthenium (L.) Gren and Gordon, Pyrethrum parthenium (L.) Bernh., and Matricaria parthenium (L.). It has been alternately described as a member of the genus Matricaria.[5,7]

The ancient Greeks called the herb “Parthenium,” supposedly because it was used medicinally to save the life of someone who had fallen from the Parthenon during its construction in the 5th century BC. The first-century Greek physician Dioscorides used feverfew as an antipyretic. Feverfew also was known as “medieval aspirin” or the “aspirin” of the 18th century.[5,8]

The plant has been used to treat arthritis, asthma, constipation, dermatitis, earache, fever, headache, inflammatory conditions, insect bites, labor, menstrual disorders, potential miscarriage, psoriasis, spasms, stomach ache, swelling, tinnitus, toothache, vertigo, and worms. Feverfew also has been used as an abortifacient, as an insecticide, and for treating coughs and colds. Traditionally, the herb has been used as an antipyretic, from which its common name is derived.[5–10]

In Central and South America, the plant has been used to treat a variety of disorders. The Kallaway Indians of the Andes mountains value its use for treating colic, kidney pain, morning sickness, and stomach ache. Costa Ricans use a decoction of the herb to aid digestion, as a cardiotonic, an emmenagogue, and as an enema for worms. In Mexico, it is used as an antispasmodic and as a tonic to regulate menstruation. In Venezuela, it is used for treating earaches.[5]

The leaves are ingested fresh or dried, with a typical daily dose of 2–3 leaves. The bitterness is often sweetened before ingestion. Feverfew also has been planted around houses to purify the air because of its strong, lasting odor, and a tincture of its blossoms is used as an insect repellant and balm for bites.[2] It has been used as an antidote for overindulgence in opium.[1]

Chemistry

The chemistry of feverfew is now well defined. The most important biologically active principles are the sesquiterpene lactones, the principal one being parthenolide. Parthenolide is found in the superficial leaf glands (0.2%–0.5%), but not in the stems, and comprises up to 85% of the total sesquiterpene content.[5,7,11]

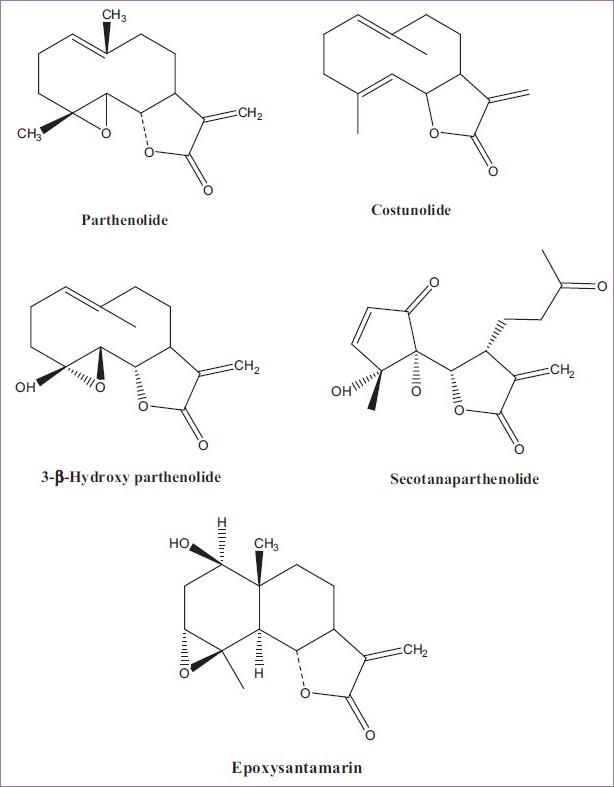

Sesquiterpene lactones

More than 30 sesquiterpene lactones have been identified in feverfew. In general, there are 5 different types of sesquiterpene lactones, which may be classified by chemical ring structures. Feverfew contains eudesmanolides, germacranolides, and guaianolides. Parthenolide is a germacranolide.[5]

Researchers have also isolated the following sesquiterpene lactones: artecanin, artemorin, balchanin, canin, costunolide, 10-epicanin, epoxyartemorin, 1-beta-hydroxyarbusculin, 3-beta-hydroxycostunolide, 8-alpha-hydroxyestagiatin, 8-beta hydroxyreynosinn, 3-beta-hydroxyparthenolide, manolialide, reynosin, santamarine, epoxysantamarine, secotanaparthenolide A, secotanaparthenolide B, tanaparthin-alpha-peroxide, and 3,4-beta-epoxy-8-deoxycumambrin B.[8] Other members of this class have been isolated and possess spasmolytic activity, perhaps through an inhibition of the influx of extracellular calcium into vascular smooth muscle cells[5,12–14] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Sesquiterpene lactones of Tanacetum parthenium

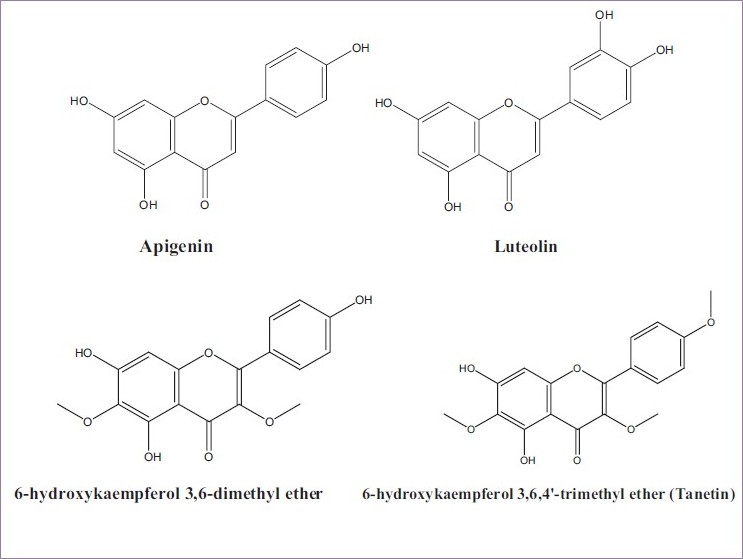

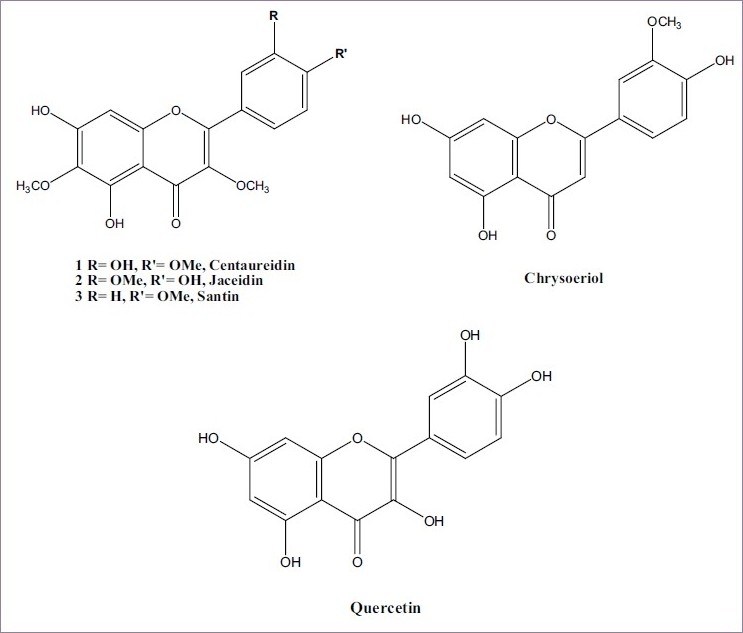

Flavonoids

The following flavonoids have been isolated: 6-hydroxykaempferol 3,6-dimethyl ether, 6-hydroxykaempferol 3,6,4′-trimethyl ether (tanetin), quercetagetin 3,6-dimethyl ether, quercetagetin 3,6,3′-trimethyl ether (accompanied by isomeric 3,6,4′-trimethyl ether), quercetin, apigenin (also apigenin 7-glucuronide), luteolin (also luteolin 7-glucuronide), chrysoeriol, santin, jaceidin, and centaureidin[15–19] [Figures 3 and 4].

Figure 3.

Flavonoids of Tanacetum parthenium

Figure 4.

Flavonoids of Tanacetum parthenium

Volatile oils

Twenty-three compounds, representing 90.1% or more of the volatile oils, have been identified from feverfew. The primary components include camphor (56.9%), camphene (12.7%), p-cymene (5.2%), and bornyl acetate (4.6%). Other components identified include tricylene, α-thujene, α-pinene, β-pinene, α-phellandrene, α-terpinene, γ-terpinene, chrysantheone, pinocarvone, borneol, terpinen-4-ol, ρ-cymen-8-ol, α-terpineol, myrtenal, carvacrol, eugenol, trans-myrtenol acetate, isobornyl 2-methyl butanoate, and caryophyllene oxide.[20]

Other chemical constituents

The coumarin isofraxidin and an isofraxidin drimenyl ether named 9-epipectachol B have been isolated from the roots of the plant; (2-glyceryl)-O-coniferaldehyde also has been isolated.[21,22]

USES AND PHARMACOLOGY

Anti-inflammatory activity

A proposed mechanism of action involves parthenolide specifically binding to and inhibiting IκB kinase complex (IKK)β. IKKβ plays an important role in pro-inflammatory cytokine-mediated signaling.[23]

Feverfew appears to be an inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis. Extracts of the above ground portions of the plant suppress prostaglandin production; leaf extracts inhibit prostaglandin production to a lesser extent. Neither the whole plant nor leaf extracts inhibit cyclooxygenation of arachidonic acid, the first step in prostaglandin synthesis. Chloroform leaf extracts, rich in sesquiterpene lactones, inhibit production of inflammatory prostaglandins in rat and human leukocytes. Inhibition was irreversible and the effect was not caused by cytotoxicity. Studies have shown that lipophilic compounds other than parthenolide may be associated with anti-inflammatory activity, particularly with reducing human neutrophil oxidative burst activity.[10,24,25]

Tanetin, a lipophilic flavonoid found in the leaf, flower, and seed of feverfew, blocks prostaglandin synthesis. Aqueous extracts do not contribute to feverfew's anti-inflammatory activity, but do prevent the release of arachidonic acid and inhibit in vitro aggregation of platelets stimulated by adenosine 5″-diphosphate (ADP) or thrombin. Whether or not these extracts block the synthesis of thromboxane, a prostaglandin involved in platelet aggregation, is controversial. Results suggest that feverfew's inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis differs in mechanism from that of the salicylates.[26–28]

Phospholipase inhibition in platelets has been documented. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthetase also has been documented for parthenolide.[29,30]

The anti-inflammatory effects of feverfew may be caused by a cytotoxic effect. Feverfew extracts were found to inhibit mitogen-induced tritiated thymidine uptake by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, interleukin-2-induced tritiated thymidine uptake by lymphoblasts, and prostaglandin release by interleukin-1-stimulated synovial cells. Parthenolide also blocked tritiated thymidine uptake by mitogen-induced human peripheral blood mononuclear cells.[31]

Effects on vascular smooth muscle

Chloroform leaf extracts of feverfew inhibited the contraction and relaxation of rabbit aorta. The inhibition was concentration and time-dependent, noncompetitive, and irreversible, occurring with or without the presence of endothelium. The leaf extracts inhibited contractions induced by potassium depolarization much less. Only fresh leaf extracts as compared with dried powdered leaves (available commercially) inhibited the effects on smooth muscle, which was likely because of a higher concentration of parthenolide. Experiments in rat and rabbit muscle using chloroform extract from fresh leaves suggest feverfew may inhibit smooth muscle spasm by blocking open potassium channels.[32–34]

Researchers have demonstrated that parthenolide noncompetitively inhibited serotonin (5-HT)-mediated spasmogenic response of indirect-acting 5-HT agonists in isolated rat stomach fundus preparation. Parthenolide noncompetitively antagonized the contractions elicited by the serotonergic drugs fenfluramine and dextroamphetamine on the fundal tissue. The mechanism of action associated with parthenolide does not involve the inhibition of 5-HT2 receptors directly, but rather occurs at the level of 5-HT stored in vesicles of the intramural neurons of fundal tissue.[35]

Effects on platelets

Extracts of feverfew inhibit platelet 5-HT secretion via neutralization of sulfhydryl groups inside or outside the cell. The sesquiterpenes in feverfew contain the alpha-methylenebutyrolactone unit capable of reacting with sulfhydryl groups. Feverfew extracts are not only potent inhibitors of serotonin release from platelets but also of polymorphonuclear leukocyte granules, providing a possible connection between the claimed benefit of feverfew in migraines and arthritis.[5,23,28,36–39]

Inhibition of histamine release

A chloroform extract of feverfew inhibited histamine release from rat peritoneal mast cells in a different manner from established mast cell inhibitors, such as cromoglycate and quercetin. The exact mechanism of action has not been determined but may be mediated by entry of calcium into mast cells.[40]

Chemotherapeutic activity

Parthenolide inhibited the growth of gram-positive bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi.[5] A hydroalcoholic extract of feverfew inhibited the growth of Leishmania amazonesis at an IC50 of 29 μg/mL, whereas a dichloromethane fraction inhibited growth at an IC50 of 3.6 μg/mL. Parthenolide has also inhibited Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium at a minimum inhibitory concentration of 16 and 64 μg/mL, respectively.[41]

Anticancer activity

Mechanisms of action may include cytotoxic action associated with interruption of DNA replication by the highly reactive lactone ring, epoxide, and methylene groups of parthenolide through inhibition of thymidine into DNA; oxidative stress, intracellular thiol depletion, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction.[5,42,43]

Parthenolide and similar lactones displayed anticancer activity against several human cancer cell lines, including human fibroblasts, human laryngeal carcinoma, human cells transformed with simian virus, human epidermoid cancer of the nasopharynx, and anti-Epstein–Barr early antigen activity. One study documents how parthenolide may influence and enhance the effectiveness of paclitaxel.[44–46]

Migraine headache, prophylactic treatment

Feverfew action does not appear to be limited to a single mechanism. Plant extracts affect a wide variety of physiologic pathways. Some of these mechanisms have been discussed previously, including inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, decrease of vascular smooth muscle spasm, and blockage of platelet granule secretion.

Clinical data

A great deal of interest has focused on the activity of feverfew in the treatment and prevention of migraine headaches.[47] The first modern, public account of its use as a preventative for migraine appeared in 1978. The story, reported in the British Health Magazine, Prevention, concerned a patient who suffered from severe migraine since 16 years of age. At 68 years of age, she began using 3 leaves of feverfew daily, and after 10 months her headache ceased completely.

A study in 8 feverfew-treated patients and 9 placebo-control patients found that fewer headaches were reported by patients taking feverfew for up to 6 months of treatment. Patients in both groups self-medicated with feverfew for several years before enrolling in the study. The incidence of headaches remained constant in those patients taking feverfew but increased almost 3-fold in patients who switched to placebo during the trial (P < 0.02).[48] The abrupt discontinuation of feverfew caused incapacitating headaches in some patients. Nausea and vomiting were reduced in patients taking feverfew, but the statistical analysis has been questioned.[49] These results were confirmed in a more recent placebo-controlled study in 72 patients suffering from migraine.[50] On the basis of their research, investigators predicted that feverfew may be useful not only for classical migraine and cluster headaches, but also for premenstrual, menstrual, and other headaches.[51]

However, studies at the London Migraine Clinic found that the experimental observations may not be clinically relevant to migraine patients taking feverfew. Ten patients who had taken extracts of the plant for up to 8 years to control migraine headaches were evaluated for physiologic changes that may have been related to the plant. The platelets of all the treated patients aggregated characteristically to ADP and thrombin similarly to those of control patients. However, aggregation in response to serotonin was greatly attenuated in the feverfew users.[52] The clinical efficacy and safety of 3 dosage regimens of a carbon dioxide (CO2) feverfew extract, each given 3 times daily, were compared with placebo in a double-blind, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. One hundred forty-seven patients suffering from migraine with or without aura according to International Headache Society criteria were treated. The primary end point was the total number of migraine attacks during the last 28 days of treatment compared with the 4-week baseline period. Secondary end points were total and average duration, intensity of migraine attacks, and number of days with accompanying migraine symptoms. There were no statistically significant effects for primary or secondary end points. Furthermore, a dose–response relationship was not observed. Subgroup analysis of 49 patients with at least 4 migraine attacks during the baseline period showed a significant effect with the 6.25 mg dose compared with placebo (P = 0.02).[53] A Cochrane review of evidence from double-blind, randomized, controlled trials was inconclusive in establishing the efficacy of feverfew for preventing migraine headaches. A total of 5 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials (343 patients) met the inclusion criteria. Results from the meta-analysis reported insufficient evidence to conclude whether feverfew was superior to placebo in reducing the frequency and severity of migraine attacks, incidence and severity of nausea and vomiting, and global assessment of efficacy in patients with migraine headaches. The dosage form varied in the trials, and thus may have impacted the results. Three trials administered dried powdered feverfew leaf extract at 50-100 mg/day for 8–24 weeks; 1 trial administered an alcoholic feverfew extract 143 mg/day for 8 weeks; 1 trial administered a CO2 extract (2.08 mg vs 6.25 mg vs 18.75 mg 3 times daily for 12 weeks). The 2 studies with the highest methodologic quality administered the alcoholic and CO2 extract and reported no benefit, whereas the studies with lower methodologic quality administered the dried powdered leaf extract reported a favorable response.[9]

Canada's Health Protection Branch granted a Drug Identification Number (DIN) for a British feverfew (T. parthenium) product, allowing the manufacturer, Herbal Laboratories Ltd, ottawa, Canada, to claim that this nonprescription drug prevents migraine headaches. The agency recommends a daily dosage of 125 mg of a dried feverfew leaf preparation from authenticated T. parthenium containing at least parthenolide 0.2% for the prevention of migraine.[54] Feverfew may produce an antimigraine effect in a manner similar to methysergide maleate (Sansert), a known 5-HT antagonist.[55,56]

Other pharmacologic effects

Monoterpenes in the plant may exert insecticidal activity, and alpha-pinene derivatives may possess sedative and mild tranquilizing effects. Extracts of the plant also inhibit the release of enzymes from white cells found in inflammed joints, and a similar anti-inflammatory effect may occur in the skin, providing a rationale for the traditional use of feverfew in psoriasis.

The effect of feverfew on rheumatoid arthritis has been investigated in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Forty-one women with rheumatoid arthritis were randomized to take placebo or feverfew 70–86 mg for 6 weeks. Of the 15 parameters tested, only grip strength improved significantly (P = 0.04) in the feverfew group compared with the placebo group. Human synovial fibroblasts express an intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) that has been implicated in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Feverfew extracts or purified parthenolide inhibited the increased expression of ICAM-1 on human synovial fibroblasts by cytokines IL-1, TNF-α, and interferon-γ.[8,57,58]

AVAILABLE FORMS

Feverfew supplements are available fresh, freeze-dried, or dried and can be purchased in capsule, tablet, or liquid extract forms. Feverfew supplements with clinical studies contain a standardized dose of parthenolide. Feverfew supplements should be standardized to contain at least 0.2% parthenolide.

DOSAGE

Pediatric

Feverfew should not be used in children younger than 2 years. In older children, adjust the recommended adult dose to account for the child's weight. Most herbal dosages for adults are calculated on the basis of an average of 150 lb (70 kg) adult. Therefore, if the child weighs 50 lb (20–25 kg), the appropriate dose of feverfew for this child would be 1/3 of the adult dosage.

Adult

For migraine headaches: Take 100–300 mg, up to 4 times daily, standardized to contain 0.2–0.4% parthenolides. Feverfew may be used to prevent or to stop a migraine headache. Feverfew supplements may also be CO2 extracted. For these, take 6.25 mg, 3 times daily, for up to 16 weeks.

For inflammatory conditions (such as arthritis): 60-120 drops, 2 times daily of a 1:1 w/v fluid extract, or 60-120 drops twice a day of 1:5 w/v tincture.[57–59]

FEVERFEW INTERACTION

Feverfew may alter the effects of some prescription and non-prescription medications. If you are currently being treated with any of the following medications, you should not use feverfew without first talking to your health care provider.[60]

Blood-thinning medications- Feverfew may inhibit the activity of platelets (a substance that plays a role in blood clotting), so individuals taking blood-thinning medications (such as aspirin and warfarin) should consult a health care provider before taking this herb.[55]

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Adverse effects of patients administered feverfew 50 mg/day (roughly equivalent to 2 leaves) during 6 months of continued treatment were mild and did not result in discontinuation. Four of 8 patients taking the plant had no adverse effects. Heart rate increased dramatically (by up to 26 beats/min) in 2 treated patients. There were no differences between treatment groups in laboratory test results. Patients who switched to placebo after taking feverfew for several years experienced a cluster of nervous system reactions (eg, headaches, insomnia, joint pain, nervousness, poor sleep patterns, stiffness, tension, tiredness) along with muscle and joint stiffness, often referred to as “postfeverfew” syndrome.[48,60]

In a larger series of feverfew users, 18% reported adverse effects, the most serious being mouth ulceration (11%). Feverfew can induce more widespread inflammation of the oral mucosa and tongue, often with lip swelling and loss of taste. Dermatitis has been associated with this plant.[40,47,61]

TOXICOLOGY

No studies of chronic toxicity have been performed on the plant and the safety of long-term use has not been established. Pregnant women should not use the plant because the leaves have been shown to possess potential emmenagogue activity. It is not recommended for lactating mothers or for use in children.[54]

One study evaluated the potential genotoxic effects of chronic feverfew ingestion in 30 migraine sufferers. Analysis of the frequency of chromosomal aberrations and sister chromatid exchanges in circulating lymphocytes from patients who ingested feverfew for 11 months found no unexpected aberrations, suggesting that the plant does not induce chromosomal abnormalities.[62]

CONCLUSION

T. parthenium (L.) contains many sesquiterpene lactones, with higher concentration of parthenolide lipophilic and polar flavonoids in the leaves and the flower heads. The plant also contains high percentage of sterols and triterpenes in the roots. Flowers and leaves and parthenolide showed significant analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activities, which confirmed the folk use of feverfew herb for treatment of migraine headache, fever, common cold, and arthritis, and these effects are attributed to leaves and/or flowers mainly due to the presence of sesquiterpene lactones and flavonoids. Feverfew also use as spasmolytic in colic, colitis and gripping, and as vermifuge and laxative. The uterine stimulant effect of the plant agreed with the folk uses of the plant as abortifacient, emmenagogue, and in certain labor difficulties and also agreed with the warning of the drug producer, which indicates the prevention of using feverfew during pregnancy but not agree with the folk use of the drug in threatened miscarriage. Taking great concern of the useful benefits of the plant, it can be advocated as a safe, highly important, medicinal plant for general mankind.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Duke JA. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1985. CRC Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson B, McDonald RL. Magic and Medicine of Plants. In: Dobelis IN, editor. Pleasantville, NY: Reader's Digest Assoc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer JE. Hammond IN: Hammond Book Co; 1934. The Herbalist. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castleman M. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press; 1991. The Healing Herbs. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chavez M, Chavez P. Feverfew. Hosp Pharm. 1999;34:436–61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain NK, Kulkarni SK. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Tanacetum parthenium L.extract in mice and rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;68:251–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heptinstall S, Awang DW, Dawson BA, Kindack D, Knight DW. Parthenolide Content and Bioactivity of Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Schultz-Bip.). Estimation of Commercial and Authenticated Feverfew Products. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1992;44:391–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1992.tb03631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Setty AR, Sigal AH. Herbal medications commonly used in the practice of rheumatology: Mechanisms of action, efficacy, and side effects. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:773–84. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pittler MH, Ernst E. Feverfew for preventing migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;1:2286. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002286.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumner H, Salan U, Knight DW, Hoult JR. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase and cyclo-oxygenase in leukocytes by feverfew.Involvement of sesquiterpene lactones and other components. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:2313–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohlmann F, Zdero C. Sesquiterpene Lactones and Other Constituents from Tanacetum parthenium. Phytochemistry. 1982;21:2543–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groenewegen WA, Knight DW, Heptinstall S. Compounds extracted from feverfew that have anti-secretory activity contain an alpha-methylene butyrolactone unit. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1986;38:709–12. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1986.tb03118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milbrodt M, Schroder F, Konig W. 3,4--Epoxy-8-deoxycumambrin B, A sesquiterpene lactone from Tanacetum parthenium. Phytochemistry. 1997;44:471–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begley M, Hewlett M, Knight D. Revised structures for guaianolide-methylenebutyro-lactones from feverfew. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:940–3. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams CA, Harborne JB, Eagles J. Variations in lipophilic and polar flavonoids in the genus Tanacetum. Phytochemistry. 1999;52:1301–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams CA, Harborne JB, Geiger H, Hoult JR. The flavonoids of Tanacetum parthenium and T. vulgare and their anti-inflammatory properties. Phytochemistry. 1999;51:417–23. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(99)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams CA, Hoult JR, Harborne JB, Greenham J, Eagles J. A biologically active lipophilic flavonol from Tanacetum parthenium. Phytochemistry. 1995;38:267–70. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(94)00609-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long C, Sauleau P, David B. Bioactive flavonoids of Tanacetum parthenium revisited. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:567–9. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall I, Lee K, Starnes C, Sumida Y, Wu R, Waddell T. Anti-inflammatory activity sesquiterpene lactones and related compounds. J Pharm Sci. 1979;68:537–42. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600680505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akpulat H, Tepe B, Sokmen A, Daferera D, Polissiou M. Composition of the essential oils of Tanacetum argyrophyllum (C. Koch) Tvzel. var. argyrophyllum and Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Schultz Bip. (Asteraceae) from Turkey. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2005;33:511–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kisiel W, Stojakowska A. A sesquiterpene coumarin ether from transformed roots of Tanacetum parthenium. Phytochemistry. 1997;46:515–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laiking S, Brown G. Coniferaldehyde derivatives from tissue culture of Artemisia annua and Tanacetum parthenium. Phytochemistry. 1999;50:781–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwok BH, Koh B, Ndubuisi MI, Elofsson M, Crews CM. The anti-inflammatory natural product parthenolide from the medicinal herb feverfew directly binds to and inhibits IkappaB kinase. Chem Biol. 2001;8:759–66. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collier HO, Butt NM, McDonald WJ, Saeed SA. Extract of feverfew inhibits prostaglandin biosynthesis. Lancet. 1980;2:922–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown AM, Edwards CM, Davey MR, Power JB, Lowe KC. Pharmacological activity of feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium [L.] Schultz-Bip.): Assessment by inhibition of human polymorphonuclear leukocyte chemiluminescence in vitro. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1997;49:558–61. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loecshe EW, Mazurov AV, Voyno-Yasenetskaya TA, Groenewegnen WA, Heptinstall S, Repin VS. Feverfew-an antithrombotic drug.? Folia Haematol Int Mag Klin Morphol Blutforsch. 1988;115:181–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makheja AN, Bailey JM. The active principle in feverfew. Lancet. 1981;2:1054–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)91256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heptinstall S, White A, Williamson L, Mitchell JR. Extracts of feverfew inhibit granule secretion in blood platelets and polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Lancet. 1985;1:1071–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makheja AN, Bailey JM. A platelet phospholipase inhibitor from the medicinal herb feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) Prostaglandins Leukot Med. 1982;8:653–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pugh WJ, Sambo K. Prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors in feverfew. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1988;40:743–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1988.tb07010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neill LA, Barrett ML, Lewis GP. Extracts of feverfew inhibit mitogen-induced human peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferation and cytokine mediated responses: A cytotoxic effect. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;23:81–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barsby RW, Salan U, Knight DW, Hoult JR. Feverfew extracts and parthenolide irreversibly inhibit vascular responses of the rabbit aorta. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1992;44:737–40. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1992.tb05510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barsby RW, Salan U, Knight DW, Hoult JR. Feverfew and vascular smooth muscle: Extracts from fresh and dried plants show opposing pharmacological profiles, dependent upon sesquiterpene lactone content. Planta Med. 1993;59:20–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barsby RW, Knight DW, McFadzean I. A chloroform extract of the herb feverfew blocks voltage-dependent potassium currents recorded from single smooth muscle cells. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1993;45:641–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1993.tb05669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bejar E. Parthenolide inhibits the contractile responses of rat stomach fundus to fenfluramine and dextroamphetamine but not serotonin. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;50:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01319-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heptinstall S, Groenewegen WA, Spangenberg P, Loesche W. Extracts of feverfew may inhibit platelet behavior via neutralization of sulphydryl groups. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1987;39:459–65. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1987.tb03420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yasenetskaya TA, Loesche W, Groenewegen WA, Heptinstall S, Repin VS, Till U. Effects of an extract of feverfew on endothelial cell integrity and on cAMP in rabbit perfused aorta. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1988;40:501–2. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1988.tb05285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heptinstall S, Groenewegen S, Spangenberg P, Losche W. Inhibition of platelet behaviour by feverfew: A mechanism of action involving sulphydryl groups. Folia Haematol Int Mag Klin Morphol Blutforsch. 1988;115:447–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krause S, Arese P, Heptinstall S, Losche W. Influence of substances affecting cell sulfhydryl/disulfide status on adherence of human monocytes. Arzneimittelforschung. 1990;40:689–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayes NA, Foreman JC. The activity of compounds extracted from feverfew on histamine release from rat mast cells. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1987;39:466–70. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1987.tb03421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tiuman TS, Ueda-Nakamura T, Garcia Cortez DA, Dias Filho BP, Morgado-Díaz JA, de Souza W, et al. Antileishmanial activity of parthenolide, a sesquiterpene lactone isolated from Tanacetum parthenium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:176–82. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.176-182.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang S, Ong CN, Shen SM. Critical roles of intracellular thiols and calcium in parthenolide-induced apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2004;208:143–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang S, Ong CN, Shen HM. Involvement of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members in parthenolide-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2004;211:175–88. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross JJ, Arnason JT, Birnboim HC. Low concentrations of the feverfew component parthenolide inhibit in vitro growth of tumor lines in a cytostatic fashion. Planta Med. 1999;65:126–9. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-13972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miglietta A, Bozzo F, Gabriel L, Bocca C. Microtubule-interfering activity of parthenolide. Chem Biol Interact. 2004;149:165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kapadia GJ, Azuine MA, Tokuda H, Hang E, Mukainaka T, Nishino H, et al. Inhibitory effect of herbal remedies on 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-promoted Epstein-Barr virus early antigen activation. Pharmacol Res. 2002;45:213–20. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feverfew-a new drug or an old wives′ remedy? Lancet. 1985;1:1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson ES, Kadam NP, Hylands DM, Hylands PJ. Efficacy of feverfew as prophylactic treatment of migraine. Br Med J. 1985;291:569–73. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6495.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waller PC, Ramsay LE. Efficacy of feverfew as prophylactic treatment of migraine. Br Med J. 1985;291:1128. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6502.1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murphy JJ, Heptinstall S, Mitchell JL. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of feverfew in migraine prevention. Lancet. 1988;2:189–92. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Groenewegen WA, Knight DW, Heptinstall S. Progress in the medicinal chemistry of the 0 herb feverfew. Prog Med Chem. 1992;29:217–38. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6468(08)70009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Biggs MJ, Johnson ES, Persaud NP, Ratcliffe DM. Platelet aggregation in patients using feverfew for migraine. Lancet. 1982;2:776. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90965-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pfaffenrath V, Diener HC, Fischer M, Friede M, Zepelin HH. The efficacy and safety of Tanacetum parthenium (feverfew) in migraine prophylaxis--a double-blind, multicentre, randomized placebo-controlled dose-response study. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:523–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Awang DV. Fever few: A headache for the consumer. HerbalGram. 1993;29:34–5. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Losche W, Mazurov AV, Heptinstall S, Groenewegen WA, Repin VS, Till U. An extract of feverfew inhibits interactions of human platelets with collagen substrates. Thromb Res. 1987;48:511–8. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(87)90383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DeWeerdt C, Bootsma H, Hendriks H. Herbal medicines in migraine prevention.Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial of a feverfew preparation. Phytomedicine. 1996;3:225–30. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(96)80057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pattrick M, Heptinstall S, Doherty M. Feverfew in rheumatoid arthritis: A double blind, placebo controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:547–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.7.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith TH, Liu X. Feverfew extracts and the sesquiterpene lactone parthenolide inhibit intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in human synovial fibroblasts. Cell Immunol. 2001;209:89–96. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palevitch D. Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) as prophylactic treatment for migraine: A double-blind placebo-controlled study. Phytother Res. 1997;11:508–11. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller LG. Herbal medicinals: Selected clinical considerations focusing on known or potential drug-herb interactions. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2200–11. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.20.2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vickers HR. Feverfew and migraine. Br Med J. 1985;291:827. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anderson D, Jenkinson PC, Dewdney RS, Blowers SD, Johnson ES, Kadam NP. Chromosomal aberrations and sister chromatid exchanges in lymphocytes and urine mutagenicity of migraine patients: A comparison of chronic feverfew users and matched non-users. Hum Toxicol. 1988;7:145–52. doi: 10.1177/096032718800700207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]