Abstract

Fluorescent proteins are convenient tools for measuring protein expression levels in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Co-expression of proteins from distinct vectors has been seen by fluorescence microscopy; however the expression of two fluorescent proteins on the same vector would allow for monitoring of linked events. We engineered constructs to allow dicistronic expression of red and green fluorescent proteins and found that expression levels of the proteins correlate with their order in the DNA sequence, with the protein encoded by the 5'-gene more highly expressed. To increase expression levels of the second gene we tested four regulatory elements inserted between the two genes: the IRES sequences for the YAP1 and p150 genes, and the promoters for the TEF1 gene from both Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Ashbya gossypii. We generated constructs encoding the truncated ADH1 promoter driving expression of the red protein, yeast-enhanced Cherry, followed by a regulatory element driving expression of the green protein, yeast-enhanced GFP. Three of the four regulatory elements successfully enhanced expression of the second gene in our dicistronic construct. We have developed a method to express two genes simultaneously from one vector. Both genes are codon-optimized to produce high protein levels in yeast, and the protein products can be visualized by microscopy or flow cytometry. With this method of regulation the two genes can be driven in a dicistronic manner, with one protein marking cells harboring the vector and the other protein free to mark any event of interest.

Keywords: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, budding yeast, dicistronic regulation, red fluorescent protein, green fluorescent protein

Introduction

Fluorescent proteins are convenient markers for measuring protein expression levels in budding yeast. The green fluorescent protein (GFP) has been widely used in yeast, inspiring a codon-optimized version for enhanced protein expression levels [Cormack et al., 1997]. Through directed evolution, several other fluorescent proteins have been generated to have similar biophysical but distinct photophysical properties as GFP [Shaner et al., 2004] and these complementary fluorescent proteins can be used in conjunction with GFP. Co-expression of two fluorescent proteins has previously been seen by fluorescence microscopy with the codon-optimized version yeast-enhanced GFP (yeGFP) and a red fluorescent protein from the Discosoma coral (DsRed) [Rodriques et al., 2001]. In co-expression studies, the two markers are generally expressed on separate vectors, with each protein's expression signifying the presence of its respective vector. However, expression of both genes from the same vector would allow for monitoring of linked events. In order to accomplish this, the two genes can be driven from a promoter and an additional regulatory element in a dicistronic manner, where one protein designates the cells harboring the vector and the other protein is free to mark any event of interest.

Small molecule inhibitors of protein function can be powerful tools for interrogating biological processes [Schreiber, 2003]. In an effort to generalize this method for regulating protein function for any protein-of-interest expressed in mammalian cells, we developed a technique to regulate the stability of an engineered protein domain using a biologically silent, cell-permeable ligand [Banaszynski, et al., 2006]. The FKBP12 protein was engineered to be unstable and rapidly degraded when expressed in mammalian cells. The instability of these FKBP12 destabilizing domains is conferred to any protein fused to them, and the cell-permeable ligand Shield-1 binds tightly to the domains, stabilizing them and preventing degradation of the protein fusion. This strategy of using our engineered destabilizing domains to confer ligand-dependent stabilization has successfully been used in several different organisms and contexts [Herm-Gotz et al., 2007; Armstrong and Goldberg, 2007; Schoeber et al., 2008; Banaszynski et al., 2008; Chu et al., 2008; Pruett-Miller et al., 2009; Madeira da Silva et al., 2009].

The destabilizing domains that are successful in mammalian cells do not confer instability to fusion proteins expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. During our attempts to engineered effective destabilizing domains to use in yeast we wished to express two distinct genes encoding fluorescent proteins from a single autonomously replicating plasmid. Dicistronic expression of (chimeric) genes would enable us to use FACS to sort a population of yeast cells based on fluorescence levels, allowing us to select for cells that harbor the vector (i.e., red fluorescence) and simultaneously exhibit our desired trait of ligand-dependent protein stability (i.e., green fluorescence in the presence of a ligand and no fluorescence in its absence).

Dicistronic regulation in yeast has not been widely studied, as the majority of eukaryotic genes are monocistronic. Thus, the majority of proteins are synthesized by the ribosome from their start to stop codons, with one mRNA transcript resulting in one protein. Translation can also occur in the presence of an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) sequence, which signals a new ribosome to bind the mRNA [Kozak, 1999]. In this case one transcript could result in two proteins, i.e. dicistronic regulation. Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been used extensively to study translation initiation, but because under normal physiological conditions the yeast translation machinery does not perform internal initiation, the type that leads to expression of more than one protein, mechanisms leading to dicistronic gene expression are still not well understood.

Many viral IRES sequences have been discovered, and although these are regularly used for dicistronic gene expression in mammalian cell culture, they have minimal or no activity in yeast [Evstafieva et al., 1993]. Two viral IRES sequences from crucifer-infecting tobacco mosaic viruses could have translation potential in live yeast; thus far one has been shown to work across other species [Dorokhov et al., 2002; Maekelaeinen and Maekinen, 2007] and the second IRES has been found to direct translation in yeast cell extracts [Altmann et al., 1990]. A cricket paralysis viral IRES also has translation potential in yeast, but until now has been used only in strains with translation-deficient mutations [Thompson et al., 2001].

A few IRES elements have been shown to work in yeast under non-physiological conditions. An IRES from the E. coli lacI gene was shown to initiate translation of a reporter gene in starved yeast cells in stationary phase, but repressed translation in a logarithmically growing culture [Paz et al., 1999]. In an in vitro translation system the leader sequences for three transcription factors (TFIID, HAP4, and YAP1) were examined for their ability to drive the expression of the luciferase reporter gene, and both TFIID and HAP4 promoted luciferase expression [Iizuka et al., 1994]. In another in vitro translation system the leader sequence for the gene TIF4631 (the mRNA is called p150), the yeast homolog of the mammalian translation initiation factor eIF4G, did not direct translation [Verge et al., 2004]. Although no translation occurred in the in vitro studies with the leader sequences for YAP1 [Iizuka et al., 1994] and p150 [Verge et al., 2004], both leader sequences did direct translation of a reporter gene in vivo [Zhou et al., 2001].

To design a dicistronic expression vector we examined the ability of the YAP1 and p150 leader sequences to initiate internal translation. We designed constructs with the gene encoding a red fluorescent protein expressed by the constitutively active ADH1 promoter and a gene encoding a green fluorescent protein driven by either an IRES (i.e., the YAP1 and p150 leader sequences) or by the constitutively active TEF1 promoters from either Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Ashbya gossypii. Dicistronic expression of two genes was achieved using either the p150 leader sequence or an additional TEF1 promoter inserted between the two genes of interest.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Biology

A vector was constructed encoding, from the 5'- to 3'-end, the gene for yeast-enhanced Cherry (yeCherry) followed by yeGFP with the putative regulatory sequence spliced in between the two reporter genes. The vector pGAD-T7 (Clontech) was modified to encode the 700-nt truncated version of the ADH1 promoter (bases 746 to 1472 at the 3’-end) in place of the full-length promoter between the SbfI and KpnI sites. A multiple cloning site with the sites SpeI, SalI, and SacII was engineered into the KpnI site and yeCherry was cloned into SpeI (5’) and SacII (3’). yeGFP was cloned into the KpnI (5’) and BglII (3’) sites of the vector. Both genes for fluorescent proteins encode start (ATG) and stop (TAG) codons. The four regulatory elements were cloned into the intervening SacII site using BsiE1 as the 5’-enzyme and SacII as the 3’-enzyme, as both enzymes leave a 3’-GC overhang. With this strategy the 5’-site is destroyed as a hybrid of BsiE1 and SacII it is resistant to both enzymes, and the 3’-site is retained as SacII. This allows the gene in the 3'-position to be replaced with other genes. The DNAs encoding the pTEF1 (S. cerevisiae), YAP1 and p150 elements were generated by PCR from genomic yeast DNA and the pTEF1 (A. gossypii) DNA was generated by PCR from vector pFA6 (EUROSCARF, Frankfurt, Germany). The sequences encoding these putative regulatory elements are provided in Figure 1. The gene encoding yeast enhanced Cherry (same protein sequence as the mCherry parent) was codon-optimized for expression in yeast by DNA 2.0 (Menlo Park, CA). The four constructs used in Figure 3 have been deposited with Addgene.

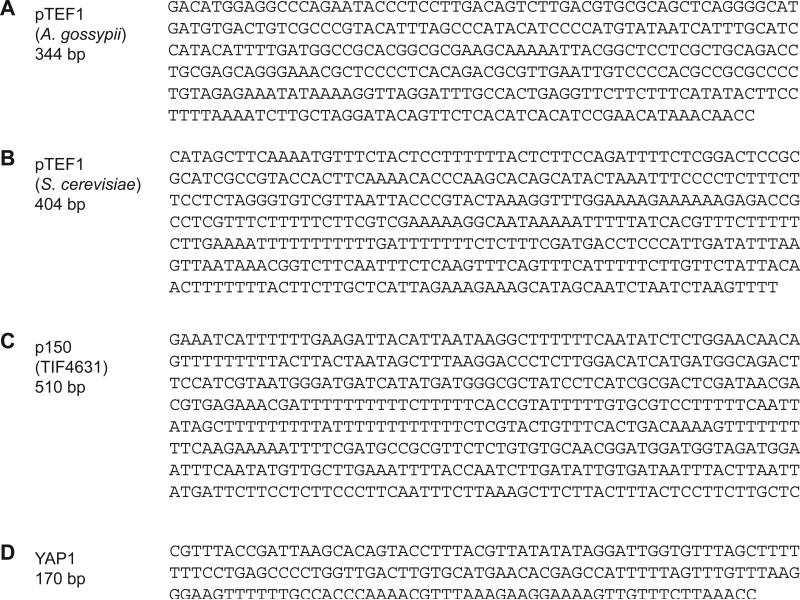

Figure 1.

Sequences of the promoter and IRES regulatory elements. (A) pTEF1 promoter from Ashbya gossypii. (B) pTEF1 promoter from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. (C) p150 leader sequence/IRES; the TIF4631 locus in yeast. (D) YAP1 leader sequence/IRES.

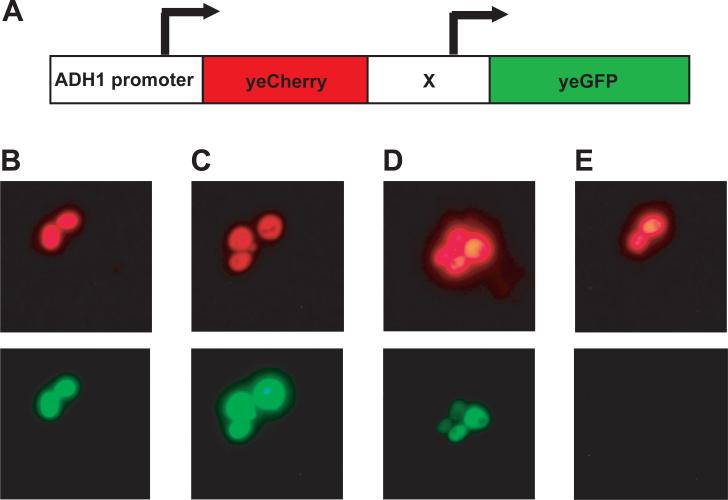

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic of the dicistronic DNA construct. The yeCherry gene is in the 5’-position driven by the 700-nt ADH1 promoter. The “X” represents one of four regulatory elements (see Figure 1) to enhance expression of the 3’-gene yeGFP. The ADH1 termination sequence follows the yeGFP gene. (B)-(E) Fluorescence micrographs of SC252a cells that harbor vectors carrying one of the four dicistronic constructs. In all cases yeCherry is the 5’-gene driven by the 700-nt ADH1 promoter. The yeGFP gene is driven by the (B) pTEF1 promoter from Ashbya gossypii, (C) pTEF1 promoter from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, (D) p150 IRES or (E) YAP1 IRES. All exposures are 0.5 seconds.

Yeast Culture

The yeast strain SC252a (ATCC, catalog number: MYA-5513) was used for all experiments. Yeast transformations were based on the standard protocol using lithium acetate [Gietz et al., 2002]. In general, 100 μL of chemically competent cells were transformed with 0.5-1 μg of vector DNA and plated under auxotrophic selective pressure. For fluorescence experiments, SC252a cells were transformed with vectors and grown for 16 h at 30 °C with shaking, under selection pressure, before fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry experiments were conducted. For fluorescence microscopy a small aliquot of cells was plated onto a glass slide and sealed with a coverslip. For flow cytometry the population of yeast cells was transferred to and analyzed from a small culture tube.

Flow Cytometry

Yeast cells were analyzed at the Stanford Shared FACS Facility on Flasher II with a minimum of 10,000 events collected for analysis. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Stanford, CA). For analysis, all cell populations were gated on healthy cells, which were represented by the oblong proportion in a FSC versus SSC plot and generally ranged from 85-95% of the total population. Cell populations were also gated on size to control for fluorescence intensities. The yeGFP (Exλ = 488 nm, Emλ = 507 nm) was excited with the 488-nm Argon laser and its fluorescence measured in the FITC channel. Cherry (Exλ= 587 nm, Emλ = 610 nm) was excited with the 598-nm laser and its fluorescence measured in the Texas Red channel.

Results and Discussion

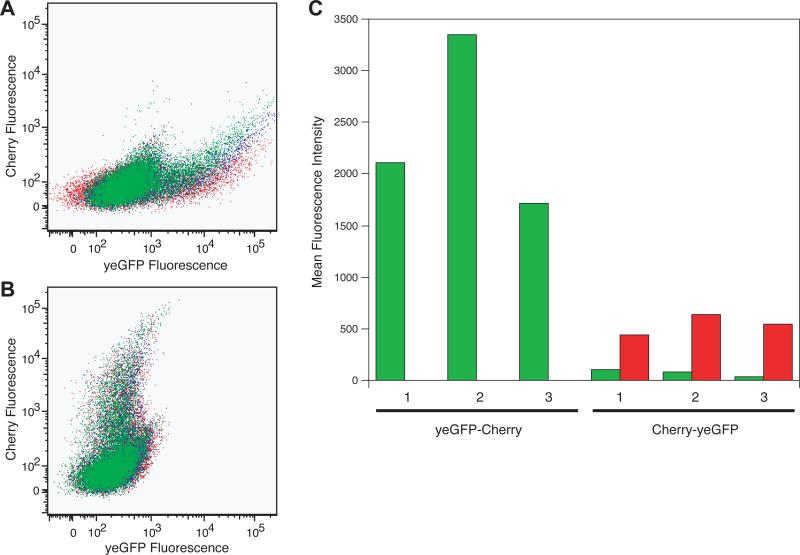

Previous work in the lab has shown that the expression levels of the proteins expressed from a dicistronic construct correlate with the order of the genes encoded by the DNA. The absence of a regulatory element, such as an IRES or an additional promoter, between the two genes results in very low levels of the second protein. Figure 2 shows this data for yeGFP and the Cherry protein (the parent version, before codon-optimizing the gene for expression in yeast). As seen in Figure 2A and 2C, in the absence of an intervening regulatory element, when the yeGFP gene occupies the 5'-position the fluorescence level of yeGFP is high and that for Cherry is undetectable. Changing the orientation of the genes so that Cherry is in the 5'-position results in a reversal of their expression levels. As seen in Figure 2B and 2C, again in the absence of an intervening regulatory element, when Cherry precedes yeGFP the fluorescence level for Cherry is moderately high and that for yeGFP is barely observable. In Figure 2C the measured levels of yeGFP vary slightly. The three experiments shown involve expression of yeGFP alone, a yeGFP-DHFR fusion, and a DHFR-yeGFP fusion in the 5'-position. We were screening for mutations in the DHFR gene that rendered the protein product more or less stable under different conditions, and we were using GFP fluorescence as a surrogate for protein stability. It has previously been observed that one can observe hypo- or hypermorphic effects when expressing a protein such as GFP in the context of a fusion protein [Butt et al, 2005], which is consistent with the modest variance in yeGFP levels that we observed.

Figure 2.

Orientation of the genes affects their expression levels. (A)-(B) show raw flow cytometry data in the form of dot plots. The x-axis displays fluorescence in the green channel and the y-axis displays fluorescence in the red channel. (A) The yeGFP gene the 5'-position and Cherry in the 3'-position. (B) Cherry gene in the 5'-position and yeGFP in the 3'-position. (C) Quantification of the mean fluorescence intensities of yeGFP and Cherry in both orientations, with green bars representing yeGFP and red bars representing Cherry. Note that this Cherry gene is not the yeast-enhanced version. Experiment 1 is yeGFP, experiment 2 is a yeGFP-DHFR fusion, and experiment 3 is the reverse orientation (DHFR-yeGFP) fusion.

To increase expression levels of the second gene we inserted four regulatory elements, two promoters and two IRES sequences, between the two genes of interest. We chose the IRES sequences for the YAP1 and p150 genes, as they were the only leader sequences shown in the literature to have in vivo activity under physiological conditions in wild-type yeast cells. In addition to two IRES elements, we also chose the strong, constitutive promoter for the TEF1 gene, which drives expression of the translation elongation factor 1 in both Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Ashbya gossypii. Some yeast vectors with dual promoters exist, however in these cases the promoters have their own multiple cloning sites and termination sequences, designed to function with separate, monocistronic expression. With our approach two promoters are cloned into the vector only 700 nucleotides apart, both driving expression of the second gene and sharing a termination sequence.

Initial experiments using the mammalian codon-optimized version of Cherry [Shaner, et al., 2004] showed that the Cherry protein is not highly expressed in yeast (Figure 2). To increase the expression of Cherry to yeGFP levels, we designed a version that was codon-optimized for yeast, referred to as yeCherry. We generated constructs with the comparably strong, constitutive 700-nt ADH1 promoter driving yeCherry expression, followed by one of these four regulatory elements driving expression of yeGFP (Figure 3A).

SC252a cells transformed with these vectors were analyzed by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy to evaluate expression levels of yeCherry and yeGFP. The images shown in Figure 3 were taken in the FITC channel for yeGFP fluorescence or the Texas Red channel for yeCherry fluorescence. Figures 3B through 3E show the fluorescence levels of the yeGFP protein driven by each of the four regulatory elements. In panel B the yeGFP fluorescence is driven by pTEF1 (Ashbya gossypii) and the level is of a similar intensity to the yeCherry fluorescence, as driven by pADH1. In panel C the yeGFP fluorescence is driven by pTEF1 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and the yeGFP signal is stronger than the yeCherry fluorescence. In panel D the yeGFP fluorescence is driven by p150 IRES and although expressed, it is of a lower intensity than the yeCherry fluorescence. In panel E the YAP1 IRES does not lead to a detectable yeGFP signal.

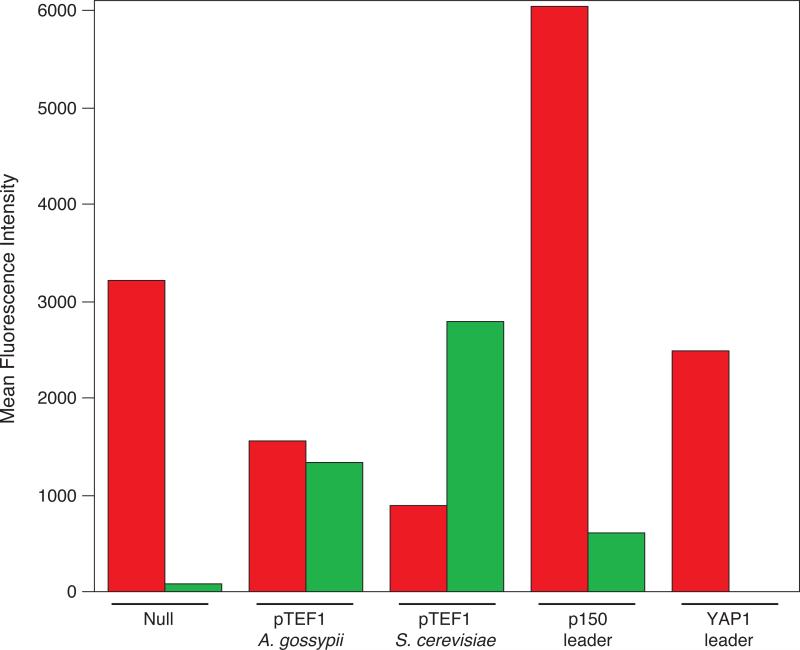

The results by flow cytometry are consistent with those by microscopy (Figure 4). The bar graph displays the mean fluorescence intensities of yeGFP (green bars) and yeCherry (red bars) for the cells harboring vectors with each of the four regulatory elements or the absence of a regulatory element (labeled “null”). In the absence of a regulatory element (the SacII restriction site is left unoccupied), yeCherry is expressed at normal levels but yeGFP is barely expressed above background levels. The YAP1 IRES, here referred to as YAP1 leader, also fails to enhance transcription of yeGFP and results in a similar fluorescence profile as the “null” construct.

Figure 4.

Mean fluorescence intensities measured by flow cytometry. The yeCherry gene is in the 5’-position driven by the 700-nt ADH1 promoter. The 3’-yeGFP gene is driven by: no additional regulatory element, designated “null”, the pTEF1 promoter from Ashbya gossypii, the pTEF1 promoter from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, p150 IRES (or p150 leader) and YAP1 IRES (or YAP1 leader). Red bars show yeCherry levels and the green bars correspond to yeGFP levels. Each bar represents the average of two fluorescence measurements.

The fluorescence levels of yeGFP are enhanced in presence of the TEF1 promoter from Ashbya gossypii, such that both yeGFP and yeCherry are expressed at similar levels (Figure 4). The TEF1 promoter from Saccharomyces cerevisiae also enhances yeGFP fluorescence. In fact, with this latter pTEF1 promoter, yeGFP is expressed 2-3-fold more strongly than yeCherry, indicating that the yeast TEF1 promoter could be even stronger than the widely-used ADH1 promoter. The p150 leader/IRES sequence also enhances yeGFP expression, albeit less strongly than either of the promoters. Both the microscopy and flow cytometry data demonstrate that expression levels of yeGFP, the protein encoded by the 3’ gene, are thus highly dependent on the presence of specific regulatory elements.

While there is the potential for gene repression due to having too much transcriptional machinery in too little space, we discovered that both promoters enhance transcription of the 3’ gene in the constructs. Three of the four regulatory elements successfully enhanced translation of the second protein in our dicistronic construct, pTEF1 (Ashbya gossypii), pTEF1 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and p150 IRES. Because yeGFP and yeCherry are expressed at comparable levels from this construct, we proceeded with the vector containing the 3’ gene driven by the pTEF1 promoter from A. gossypii.

We have developed a method to express the genes encoding two fluorescent proteins simultaneously from one vector. Both genes are codon-optimized for high expression in yeast and can be easily visualized using microscopy or flow cytometry (FACS). With this method of regulation the two genes can be driven in a dicistronic manner, with one protein marking cells harboring the vector and the other protein free to mark any event of interest. This technique should facilitate the systematic analysis of protein function.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Angela Chu (Ron Davis lab) and Ling-chun Chen for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the NIH (GM 068589)

References

- Altmann M, Blum S, Wilson TM, Trachsel H. The 5'-leader sequence of tobacco mosaic virus RNA mediates initiation-factor-4E-independent, but still initiation-factor-4A-dependent translation in yeast extracts. Gene. 1990;91:127–129. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90173-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong CM, Goldberg DE. An FKBP destabilization domain modulates protein levels in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Meth. 2007;4:1007–1009. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banaszynski LA, Wandless TJ. Conditional Control of Protein Function. Chemistry & Biology. 2006;13:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banaszynski LA, Chen L-C, Maynard-Smith LA, Ooi AGL, Wandless TJ. A rapid, reversible and tunable method to regulate protein function in living cells using synthetic small molecules. Cell. 2006;126:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banaszynski LA, Sellmyer MA, Contag CH, Wandless TJ, Thorne SH. Chemical control of protein stability and function in living animals. Nat Med. 2008;14:1123–1127. doi: 10.1038/nm.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt TR, Edavettal SC, Hall JP, Mattern MR. SUMO fusion technology for difficult-to-express proteins. Protein Expression & Purification. 2005;43:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BW, Banaszynski LA, Chen LC, Wandless TJ. Recent progress with FKBP-derived destabilizing domains. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5941–5944. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack BP, Bertram G, Egerton M, Gow NAR, Falkow S, Brown AJP. Yeast-enhanced green fluorescent protein (yEGFP): a reporter of gene expression in Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1997;143:303–311. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorokhov YL, Skulachev MV, Ivanov PA, Zvereva SD, Tjulkina LG, Merits A, Gleba YY, Hohn T, Atabekov JG. Polypurine (A)-rich sequences promote cross-kingdom conservation of internal ribosome entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5301–5306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082107599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SR, Wandless TJ. The rapamycin-binding domain of the protein kinase mammalian target of rapamycin is a destabilizing domain. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13395–13401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700498200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evstafieva AG, Beletsky AV, Borovjagin AV, Bogdanov AA. Internal ribosome entry site of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA is unable to direct translation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1993;335:273–276. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80745-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Woods RA. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herm-Gotz A, Agop-Nersesian C, Munter S, Grimley JS, Wandless TJ, Frischknecht F, Meissner M. Rapid Control of Protein Levels in the Apicomplexan Parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Nat Meth. 2007;4:1003–1005. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka N, Najita L, Franzusoff A, Sarnow P. Cap-dependent and cap-independent translation by internal initiation of mRNAs in cell extracts prepared from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7322–7330. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. Initiation of translation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Gene. 1999;234:187–208. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira da Silva L, Ownes KL, Murta SMF, Beverley SM. Regulated expression of the Leishmania major surface virulence factor lipophosphoglycan using conditionally destabilized fusion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7583–7588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901698106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekelaeinen KJ, Maekinen K. Testing of internal translation initiation via dicistronic constructs in yeast is complicated by production of extraneous transcripts. Gene. 2007;391:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz I, Abramovitz L, Choder M. Starved Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells have the capacity to support internal initiation of translation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21741–21745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett-Miller SM, Reading DW, Porter SN, Porteus MH. Attenuation of zinc finger nuclease toxlcity by small-molecule regulation of protein levels. PLoS Genetics. 2009;5:e1000376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriques F, Van Hemert M, Steensma HY, Corte-Real M, Leao C. Red fluorescent protein (DsRed) as a reporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bact. 2001;183:3791–3794. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.12.3791-3794.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober JPH, van de Graaf SFJ, Lee KP, Wittgen HGM, Hoenderop JGJ, Bindels RJM. Conditional fast expression and function of multimeric TRPV5 channels using Shield-1. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2009;296:F204–F211. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90473.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber SL. The small-molecule approach to biology: chemical genetics and diversity-oriented organic synthesis make possible the systematic exploration of biology. Chem. Eng. News. 2003;81:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BNG, Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Improved monomeric red, orange, and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotech. 2004;22:1567–1572. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SR, Gulyas KD, Sarnow P. Internal initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mediated by an initiator tRNA/eIF2-independent internal ribosome entry site element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12972–12977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241286698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verge V, Vonlanthen M, Masson J-M, Trachsel H, Altmann M. Localization of a promoter in the putative internal ribosome entry site of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae TIF4631 gene. RNA. 2004;10:277–286. doi: 10.1261/rna.5910104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Edelman GM, Mauro VP. Transcript leader regions of two Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNAs contain internal ribosome entry sites that function in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1531–1536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]