Abstract

GIV/Girdin is a multidomain signaling molecule that enhances PI3K-Akt signals downstream of both G protein-coupled and growth factor receptors. We previously reported that GIV triggers cell migration via its C-terminal guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) motif that activates Gαi. Recently we discovered that GIV's C-terminus directly interacts with the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and when its GEF function is intact, a Gαi-GIV-EGFR signaling complex assembles. By coupling G proteins to growth factor receptors, GIV is uniquely poised to intercept the incoming receptor-initiated signals and modulate them via G protein intermediates. Subsequent work has revealed that expression of the highly specialized C-terminus of GIV undergoes a bipartite dysregulation during oncogenesis—full-length GIV with an intact C-terminus is expressed at levels ∼20–50-fold above normal in highly invasive cancer cells and metastatic tumors, but its C-terminus is truncated by alternative splicing in poorly invasive cancer cells and non-invasive tumors. The consequences of such dysregulation on graded signal transduction and cellular phenotypes in the normal epithelium and its implication during tumor progression are discussed herein. Based on the fact that GIV grades incoming signals initiated by ligand-activated receptors by linking them to cyclical activation of G proteins, we propose that GIV is a molecular rheostat for signal transduction.

Key words: G proteins, girdin, guanine nucleotide exchange factor, epidermal growth factor-receptor, G protein coupled receptors, metastasis, migration-proliferation dichotomy, growth factors, alternative splicing, PI3-kinase, Akt, rheostat, actin cytoskeleton

Introduction

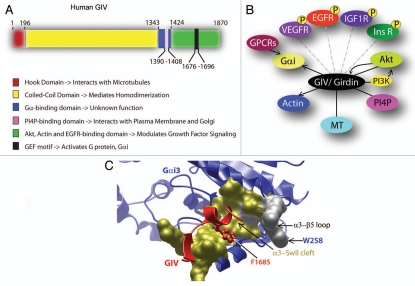

GIV (a.k.a, Gα Interacting, Vesicle-associated protein; Girdin) is a large, multidomain protein (Fig. 1A) that was independently discovered by 4 different groups: based on GIV's ability to bind Gαi3 and localize to COPI transport vesicles, we proposed that GIV may link G protein signaling to trafficking events at the Golgi;1 based on GIV's ability to bind microtubules, Simpson et al. proposed that GIV participates in growth factor receptor endocytosis,2 and based on GIV's ability to interact with Akt, actin and phosphatidylinositol 4′-monophosphate (PI4P), Anai et al. and Enomoto et al. proposed that GIV enhances Akt signals3 and couples them to actin remodeling at the leading edge of migrating cells.4,5 From subsequent work GIV has emerged as a protein that is indispensable for both signal transduction and cell migration during a variety of physiologic and pathologic processes, i.e., wound healing,4,6 macrophage chemotaxis,6 tumor cell migration,4,6–8 and endothelial cell migration during angiogenesis.9 A key finding we made was that activation of Gi is required for GIV to perform its functions during cell migration:6 activation of Gαi triggered redistribution of GIV from its major intracellular pool in the Golgi region to the cell periphery. Consistent with its role in such diverse cell types and biological processes, GIV's ability to trigger cell migration or amplify Akt signals is not restricted to a single set of stimuli, receptor or class of receptors. We6,7,10 and others4,5,8,9 have demonstrated that multiple members of two large and distinct classes of receptors—G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs, e.g., fMLPR and LPAR) and growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs, e.g., EGFR, VEGFR, IGF1R, InsR) require GIV to enhance Akt signals and trigger cell migration. Thus, GIV serves as a common platform where incoming signals (primarily Akt and other signals) initiated by multiple activated receptors at the leading edge are amplified by activation of G proteins and coupled with actin within pseudopods in migrating cells (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

GIV is a multidomain signaling molecule with key interacting partners. (A) Functional domains of GIV. The N-terminal Hook domain (red) interacts with microtubules,2 the coiled-coil domain (yellow) mediates homodimerization,4 the Gα-binding domain (GBD, blue) interacts with α-subunits of Gαi,1 a lipid (PI4P)-binding domain (pink) mediates interaction with the Golgi and the plasma membranes,4,5 and the extreme C-terminus (green) interacts with EGFR,14 Akt kinase and actin.3,4 The key regulatory component of GIV, i.e., the GEF domain (black) with which GIV interacts and activates Gαi, is located within the C-terminus.7 (B) GIV interacts with multiple signaling molecules and cytoskeletal proteins. GIV/Girdin triggers migration and enhances PI3K-Akt signals downstream of a variety of growth factor receptors (VEGFR,9 EGFR,4,14 IGFR8 and InsR7,41). GIV is also required for enhancement of PI3K-Akt signals downstream of GPCRs.6,7,10 GIV's C-terminal GEF domain activates Gαi7 and couples G proteins to multiple ligand-activated receptors.14 GIV is both an enhancer of Akt kinase and a substrate of the kinase,4 perhaps providing a feedback loop within the ‘receptor-GIV-PI3K-Akt’ signaling axis. GIV also interacts with 3 key structural components—actin, microtubules (MT) and PI4P-enriched membranes (Golgi and the PM) which serve to further compartmentalize and target GIV-dependent signaling pathways. (C) The Gαi-GIV interface is a unique therapeutic target. GIV is the first non-receptor GEF for heterotrimeric G proteins that works via a novel, evolutionarily conserved motif. The structure of GIV's GEF motif in complex with Gαi3 was initially modeled based on its homology with the synthetic KB-752 peptide in complex with Gαi1 and subsequently validated by site directed mutagenesis.7 GIV's GEF motif (red) docks on the hydrophobic cleft formed between Gαi3's α3 helix and the switch II (gold surface) via F1685.7 In addition, W258 in the α3/β5 loop of Gαi3 is an essential structural determinant that renders the G protein sensitive to activation by GIV. Importantly, the conservative substitution of W258 for F disrupts Gαi's ability to bind GIV, but it does not perturb its interaction with other binding partner such as Gβγ, GDIs, GAPs or GPCRs,10 which demonstrates that the Gαi-GIV interaction can be selectively targeted without compromising other functions of Gαi subunits. The uniqueness of the Gαi-GIV molecular interface, the selectivity of the structural determinants required to assemble it and its critical role in promoting the prometastatic functions associated with GIV expression in tumor cells make it a novel and attractive pharmacological target in cancer therapeutics.

Although the molecular basis for how GIV may serve within the signaling cascades of such diverse receptors remained unknown, clues pointing to its importance in disease, in particular during tumor invasion, emerged early.4,5 We reported that among colon cancer cell lines full-length GIV (mRNA and protein) was expressed exclusively in those with high metastatic potential,6 and others demonstrated that some but not all tumors express GIV.9 Subsequently, Jiang et al. demonstrated that breast cancer cell lines depleted of GIV were unable to metastasize efficiently in murine models of tumor invasion.8 In addition, using an in vivo murine Matrigel plug assay Kitamura et al. demonstrated the role of endothelial GIV-fl in VEGF-mediated neoangiogenesis, a prerequisite for tumor progression. While investigating the molecular basis for these “pro-metastatic” functions of GIV (i.e., Akt signal enhancement and actin cytoskeleton remodeling during tumor cell migration) we discovered that GIV is a non-receptor Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor (GEF) for Gαi.7 GIV binds selectively and specifically to the Gαi1/2/3 subunits and activates them via an evolutionarily conserved, C-terminal GEF motif (amino acids 1,676–1,696). We demonstrated that activation of Gαi by GIV promotes the release of ‘free’ Gβγ subunits, which subsequently enhance PI3K-Akt signals via the previously characterized11,12 Gβγ-PI3K pathway. Using structure homology modeling, bioinformatics and mutagenesis approaches we determined that GIV and Gαi3 interact through a unique molecular interface7,10 (Fig. 1C). Disruption of this interface in vivo either by changing a single, key amino-acid in GIV (Phenylalanine, F1685↑Alanine, A7) or in Gαi3 (Tryptophan, W258↑F10) virtually abolishes all the pro-metastatic phenotypes that are associated with expression of GIV—i.e., Akt enhancement and actin remodeling during tumor cell migration. We envision that the uniqueness of the GIV-Gαi interface, its sensitivity to disruption and its specificity within a clinically-relevant signaling pathway, all indicate that it could be exploited as a novel pharmacological target. We proposed7 that small molecular inhibitors that specifically disrupt the GIV-Gαi interface are likely to have anti-metastatic action.

Despite the breadth of information available on the molecular and biological functions of GIV-fl during cancer invasion and angiogenesis,3–10 the molecular basis for many observations remained unanswered. Of these, two questions challenged us the most. First, given that the Gαi-GIV axis of signal transduction is utilized efficiently by both GPCRs and RTKs, we wondered how do multiple growth factor RTKs utilize Gαi and GIV to amplify Akt signals that they initiate? Although it is conceivable that G proteins serve as the linker allowing GPCRs to access Gαi-GIV-dependent signaling, we wondered if GIV might serve as a linker between RTKs and a G protein pathway. The second question that intrigued us was, how and why do some tumors and tumor cells overexpress GIV,6,8,13 whereas others silence this protein? Given that all tumor cells have proliferative, invasive and survival advantage over normal epithelial cells, does both the absence and overexpression of GIV provide the tumor cells with a distinct set of phenotypic advantages? How would such phenotypic advantages enable tumor progression? Our recent work, in reference 14, provides some answers to both these questions. Here we dissect the implications of our latest findings on GIV, with a particular focus on its unique ability to link G proteins to ligand-activated RTKs and thereby amplify incoming signals via dual pathways during tumor progression. Other functions of GIV, namely its ability to bind Akt and remodel the cytoskeleton in physiology and disease has been reviewed in-depth by others.5,15

GIV Directly Links G Proteins to Activated EGF Receptors and Modulates EGF Signaling

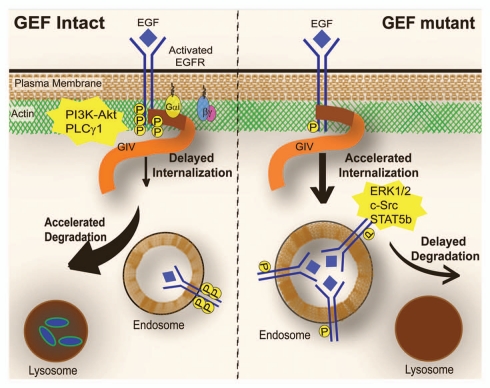

Using epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), the prototype member of the growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase family, we demonstrated14 that GIV's C-terminus directly binds the autophosphorylated cytoplasmic tail of EGFR, most likely at the plasma membrane (PM) where they colocalize and thereby links G protein to ligand-activated receptors. We found that formation of such a Gαi-GIV-EGFR ternary complex at the receptor tail, dictates several closely intertwined spatial and temporal aspects of post-receptor EGF-signaling, e.g., extent of receptor autophosphorylation, recruitment of Srchomology 2 (SH2)-domain containing adaptors, downstream signaling via such SH2 adaptors, trafficking and endolysosomal degradation of the receptors (Fig. 2). When GIV's C-terminus and its GEF motif are intact, a Gαi-GIV-EGFR ternary complex is successfully assembled, EGFR autophosphorylation is enhanced, and the receptor's association with the PM is prolonged. Accordingly, PM-based motogenic signals (i.e., PI3K-Akt and PLCγ1 signals that are known to preferentially trigger motility) are amplified, actin is remodeled and cell migration is triggered. Thus, GIV's C-terminus serves as a common platform which links ligand-activated receptors14 at the leading edge to actin,4 Akt3–5 and Gαi,7 three components whose interplay is essential for cell migration. By contrast, in cells expressing a mutant GIV lacking its entire C-terminus or specifically, the GEF motif, the GIV-Gαi-EGFR signaling complex is not assembled. As a consequence EGFR autophosphorylation is reduced, the receptor's association with endosomes is prolonged, mitogenic (i.e., ERK1/2 and Src-STAT5 signals that are known to preferentially trigger mitosis) signals are amplified and cell proliferation is triggered. Thus, we defined a novel role for GIV's GEF domain and G protein activation in modulating EGF signaling.

Figure 2.

GIV links G protein to ligand activated EGFR and regulates EGFR localization, EGFR degradation and EGF signaling. Schematic illustration of the EGFR itinerary and signaling profiles in cells expressing wild-type GIV with an intact GEF motif (left) and those expressing a GEF-deficient mutant of GIV (right). When GIV's GEF motif is intact, activation of Gαi is coupled to the ligand-activated EGFR via GIV, the duration and extent of receptor autophosphorylation and receptor association with the PM is enhanced, and the rate of receptor internalization is delayed. However, once internalized, the receptor rapidly transits through the endolysosomal compartments and receptor degradation is accelerated in lysosomes. By contrast, when GIV's GEF motif is disabled, Gαi is not activated in the vicinity of the receptor, receptor autophosphorylation is reduced, and it is rapidly internalized within endosomes where it stays for longer duration due to delayed receptor degradation. As a direct consequence of differential receptor association with the PM-actin bed, PM-based motogenic (PI3K-Akt and PLCγ1) signals are enhanced only when GIV's GEF motif is intact, whereas when GIV's GEF domain is disabled, mitogenic (c-Src, STAT5b and ERK1/2) signals are sustained from intracellular membranes.

These differences in receptor localization and contrasting profiles of EGFR-initiated signals we observe in the presence or absence of GIV's GEF motif are in keeping with prior reports that the signaling profile of activated receptors is largely determined by the compartment in which they are located16–19 (Fig. 2). For example, motogenic signals are initiated and coupled to actin remodeling exclusively by receptors at the PM to preferentially trigger motility whereas internalized receptors preferentially propagate mitogenic signals, presumably from endosomes.20 These differences in EGFR signaling have been attributed to the levels of PI4,5P2, a critical and common substrate of the two key motogenic enzymes, PI3K and PLCγ1, which are enriched at the PM but depleted at endosomes.16 Based on these considerations we proposed14 that motogenic PI3K and PLCγ1 signals are enhanced in the presence of an intact GEF motif, most likely due to the persistence of activated receptor at the PI4,5P2-enriched PM, and inhibited in the absence of a GEF motif, most likely due to accumulation of activated receptor in the PI4,5P2-depleted endosomes.

Taken together, we demonstrated that the presence or absence of GIV's GEF function determines whether G proteins are coupled to ligand-activated EGFR and affect activation of G protein intermediates near the vicinity of such activated receptors, which in turn regulates spatial and temporal aspects of EGFR signaling. The molecular mechanisms by which GIV's GEF function helps govern EGFR distribution and regulate its fate remain to be elucidated.

Divergent EGF-Signaling Programs Orchestrate Migration-Proliferation Dichotomy

Although previous work predicted a central role for EGFR in migration-proliferation dichotomy21 and demonstrated that the distinct sets of signaling pathways that lead to motility or cell proliferation diverge at the immediate post-receptor phase,22 the exact molecular mechanism had remained elusive. We have defined the point of divergence as the receptor tail, where GIV binds by showing that the presence or absence of GIV's GEF function regulates Gαi recruitment to receptor tail and fine tunes divergent EGFR signaling programs through G protein pathways such that cells are biased to migrate or proliferate. Our finding that G protein activation via GIV's GEF motif plays a key role in orchestrating this migration-proliferation dichotomy is also consistent with previous work demonstrating that migration is triggered by active Gαi3,6 but mitosis is enhanced in the absence of Gαi activation.23 Based on our findings we concluded that both G protein and growth factor signaling operate through GIV and participate in establishing migration-proliferation dichotomy and that the presence or absence of GIV-dependent Gαi activation is crucial for this phenotypic dichotomy to take place.

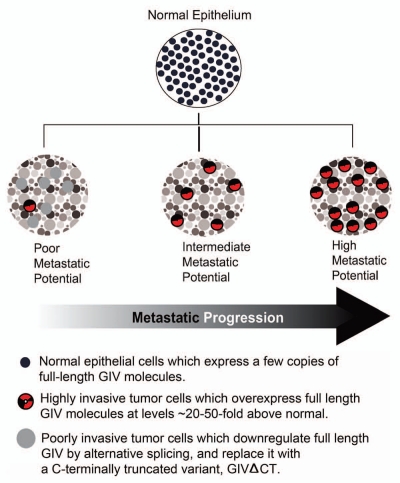

Migration-Proliferation Dichotomy in Tumor Cells Stems from Dysregulated Expression of GIV

Our findings shed light on the enigmatic origin of migration-proliferation dichotomy that is observed not only in cancer progression,24,25 but also during epithelial wound healing26–28 and development.29,30 In the context of cancer progression, migration-proliferation dichotomy during tumor invasion has been attributed to differential signaling downstream of EGFR.21 We found that in rapidly growing, poorly motile breast and colon cancer cells and in non-invasive colorectal carcinomas in situ, in which EGFR signaling favors mitosis over motility, full-length GIV is alternatively spliced to generate GIVΔCT, a C-terminally truncated, GEF-deficient, splice variant that endows cells with a proliferative advantage. Introduction of increasing copies of full-length GIV (with an intact GEF motif) into these cells was accompanied by a proportionate increase in Akt phosphorylation and efficiency of cell migration in a gradient fashion,7 much like the intensity of light is increased in a continuous gradient due to the presence of a rheostat within the circuit. As the tumor progresses and gets populated by highly motile but slow-growing cancer cells in late invasive carcinomas, the pattern of GIV expression among tumor cells shifts such that full-length GIV is highly expressed at levels ∼20–50 fold above normal and has an intact GEF motif which endows tumor cells with an invasive advantage (Fig. 3). This shift in tumor composition is in keeping with studies demonstrating that phenotypic heterogeneity exists among cells within the same tumor.24,25 Phenotypic heterogeneity has remained a challenge in treatment of carcinomas because only the actively proliferating cells are the most vulnerable to chemotherapy, whereas the nonproliferating cells that are actively invading are resistant to anti-cancer drugs.31 Our findings indicate that alternative splicing of GIV's C-terminus regulates the total copies of full-length GIV expressed in tumor cells, which helps grade receptor initiated signaling pathways, in particular, the PI3K-Akt signals over a broad range like a rheostat. This type of graded signaling is key to balancing tumor cell proliferation and migration, which most likely contributes to phenotypic heterogeneity within a tumor and thereby influences early tumor growth as well as late metastatic invasion. We have subsequently demonstrated13 that tumors comprised of highly proliferative, poorly invasive cells expressing GIVΔCT have increased DNA microsatellite instability and tend to grow larger in size but metastasize poorly and carry a good prognosis, whereas those comprised of highly invasive cells expressing full-length GIV tend to metastasize early and are associated with poor survival. Thus, inclusion or exclusion of GIV's C-terminus, which contains the critical GEF motif that activates Gi and the EGFR-binding domain that presumably modulates receptor signaling, is one of the mechanisms that may drive cancer progression by enhancing both early tumor growth and late tumor invasion.

Figure 3.

Expression of GIV is dysregulated during cancer progression. Schematic illustration of changes in GIV expression in epithelial cells during transition from normal to cancer and during metastatic progression is displayed. While a non-invasive tumor with poor metastatic potential is largely comprised of poorly invasive tumor cells that express GIVΔCT, invasive tumors with high metastatic potential are populated by highly invasive tumor cells that overexpress full-length GIV.

New Perspectives and Future Directions

GIV is a novel phosphotyrosine binding protein that directly binds growth factor receptors and grades the signals they initiate.

By demonstrating that GIV's C-terminus directly binds autophosphorylated cytoplasmic tails of ligand-activated growth factor receptors our work has shed some light on the nature of the anatomical link between GIV and RTKs. Because GIV's C-terminus exclusively binds the tyrosine phosphorylated cytoplasmic tail of EGFR, this feature qualifies GIV as a novel phosphotyrosine binding protein. Although traditional domain-prediction programs have failed to identify a canonical domain for phosphotyrosine recognition, it is possible that GIV contains non-canonical Phospho-Tyrosine-Binding (PTB) or SH2 domains that are not predicted by conventional domain search programs. Because GIV enhances signals downstream of multiple growth factors (EGF, VEGF, Insulin, IGF), it is tempting to speculate that such a common structural mechanism may allow GIV to also couple with their respective receptors. Existence of such a common mechanism may explain the diverse biological functions GIV regulates, i.e., migration, proliferation, autophagy, angiogenesis and neurodevelopment. Competitive binding of GIV to phosphotyrosines on the EGFR tail is likely to affect the recruitment and downstream functions of other SH2/PTB domain-containing adaptors,32 thereby accounting for the altered kinetics of receptor internalization, dephosphorylation and degradation we observed within the endolysosomal system.14 Because GIV has an actin binding domain4 and EGFR-actin association is known to increase the longevity of activated receptor at the PM during cell migration,33,34 GIV may alternatively enhance receptor signaling simply via stabilization of EGFR-actin associations at the PM. A complete understanding of the structural basis for GIV's ability to recognize and bind ligand-activated RTKs would go a long way toward clarifying the precise molecular mechanism by which GIV affects RTK signaling. Efforts are underway to not only identify the precise amino-acids/domains that mediate the interaction between GIV and EGFR, but also to test whether identical aminoacids/domains mediate the interactions between GIV and other RTKs that also signal via GIV (Fig. 1B). If a common structural basis underlies the formation of any GIV-RTK interface, that interface can serve as yet another target to simultaneously modulate signaling pathways triggered by multiple receptors, all of which converge upon GIV.

Regulatory networks that target GIV and its highly specialized C-terminus in health and disease.

The transformation of a normal cell into a cancer cell has been correlated with dysregulated expression of a myriad of genes/proteins;35–37 while some are upregulated, others are downregulated. We found that expression of GIV, and more specifically its C-terminus, is dysregulated in a bipartite manner during tumor progression, i.e., downregulated by alternative splicing early during tumor growth and upregulated later during tumor invasion. This bipartite pattern of dysregulation functions much like a double-edged sword, in that up and downregulation of GIV's C-terminus confer distinct advantageous phenotypes to tumor cells. To the best of our knowledge, there is no other protein that is similarly dysregulated during cancer progression. Despite the insights gained, many questions remain unanswered.

Although we identified a tumor-specific GIVΔCT variant that triggers mitosis, the splicing factor whose deficiency might trigger such a missplicing event remains unknown. Unlike poorly invasive tumor cells, in normal epithelial cells and in highly invasive tumor cells GIV is constitutively and efficiently spliced, and no mutations were found at or near the splice site that could account for aberrant pre-mRNA splicing. Based on these findings we speculated14 that extrinsic factors, e.g., differential expression of splicing factors during cancer progression,38 may restrict GIVΔCT expression to poorly invasive cells. Because the level of GIV mRNA is downregulated early during tumorigenesis by alternative splicing, it is likely that the splicing factor that normally maintains the fidelity of GIV pre-mRNA processing is also downregulated during early tumor growth. Further studies are warranted to identify the candidate splicing factor. Finally, it is also possible that GIV is downregulated in poorly invasive cells by microRNAs (miRNAs). miRNAs are small RNA molecules that provide a major and key layer of post-transcriptional control within the networks of gene regulation,39 and one such microRNA, miR-451, has been implicated in migration-proliferation dichotomy during cancer progression.40 While it is known that miRNAs are globally downregulated during cancer progression,39 it remains to be seen if GIV is a target of miR-451 early during tumor growth. The mechanism(s) by which highly invasive cancer cells upregulate GIV (both, mRNA and protein) is also poorly understood. In this regard, it would be important to distinguish if increased mRNA levels are a consequence of increased transcription or post-transcriptional mRNA stabilization or both, and whether increased protein levels are due to enhanced folding and stabilization of the newly synthesized GIV molecules. Whatever the mechanism might be, it is clear that while transient increases in GIV expression may occur in physiology (for example, during early phases of epithelial wound healing) and might be required for temporary upregulation of PI3K-akt signals to trigger efficient cell migration, sustained increases in GIV aberrantly grade PI3K-Akt signals, which in turn bears deleterious consequences for normal epithelial cells.

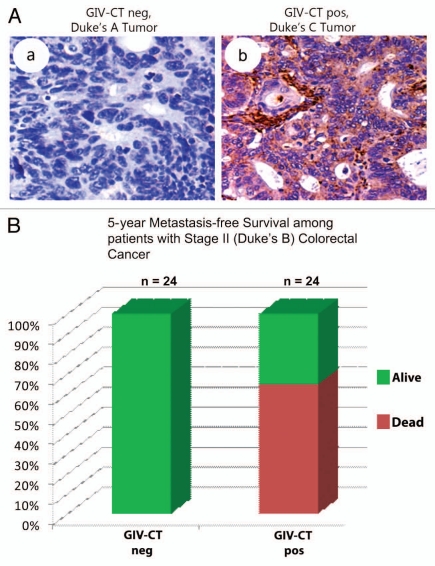

With regard to the clinical importance of the bipartite dysregulation of GIV, in a follow-up study13 we showed that the presence of the critical C-terminus can distinguish highly metastatic from poorly metastatic cancers and thereby prognosticate survival among cancer patients. We defined full-length GIV (GIV-fl) as a metastasis-related protein whose expression effectively identifies those cancers that carry “high-invasion-poor-prognosis” signature. Because the presence of GIV's C-terminus distinguishes tumor cells with highest invasiveness/metastatic potential from others, we concluded that alternative splicing of GIV's C-terminus is one of the key mechanisms that impart ‘metastasis-related’ properties to the GIV-fl gene. We further demonstrated that expression of GIV-fl increases during metastatic progression and effectively prognosticates survival in a cohort of patients in whom the tumor is of an intermediate stage where prognostication is extremely challenging (Fig. 4). Thus, detection of GIV's C-terminus can serve as an attractive, conserved and convenient target for use as a mechanistically identified, metastasis biomarker for carcinomas. Together with the fact that we recently identified GIV's C-terminal GEF motif as a potential therapeutic target in our armamentarium against cancer metastasis,7,10 these recent findings promise an opportunity for the practice of personalized medicine. Patients with poor prognosis-bearing, GIV-fl-positive tumors could qualify for an adjuvant therapy in the form of inhibitors of this critical GIV-dependent signaling pathway. Finally, our recently completed work41 investigating the role of GIV in regulating the PI3K-mTOR pathway downstream of yet another growth factor RTK, the insulin receptor, has revealed that cellular autophagy, a major catabolic pathway in physiology and in disease,42 is tightly regulated by GIV's GEF motif. Since “grow vs. go” behavior of tumor cells has previously been linked also to cellular energy and availability of nutrition,43 it is possible that GIV may impact metabolic (anabolic or catabolic) pathways in tumor cells.

Figure 4.

Expression of full-length GIV increases correlation with metastatic progression and prognosticates metastasis-free survival in cancer patients. (A) Cells expressing a C-terminally truncated GIV (GIV-CT neg) dominate non-invasive tumors (a), whereas those with increased fulllength GIV (GIV-CT pos) are found in invasive tumors (b). Paraffin embedded human colon cancer samples were analyzed for full-length GIV by immunohistochemistry using GIV-CT Ab. Upper parts display representative fields from a non-invasive (Duke's A) tumor of early clinical stage (a) and invasive (Duke's C) tumors of late clinical stages (b). Non-invasive Duke's A tumor cells (a) stain negatively for GIV CT whereas invasive Duke's C tumors (b) are strongly positive. The percent of GIV-CT-positive tumors increases with increasing clinical stage of colorectal carcinoma-0% for Dukes A (early-staged tumor localized to mucosa), ∼48% for B (intermediate-staged tumor limited to muscularis propria) and 100% for C (advanced tumor spreads to local lymph nodes) and D (tumors with distant metastases). Parts reproduced with permission from Ghosh et al. MBoC, 2010.14 (B) Expression of full-length GIV prognosticates 5-year metastasis-free survival among patients with Stage II (Intermediate, Duke's B) colorectal carcinoma. Paraffin embedded human colon cancer samples of Duke's clinical stage B2 were analyzed for full-length GIV as in (A). Staining was scored as negative or positive by three independent observers blinded to patient outcome and stage with >95% congruency. At the 5-year mark, survival was 100% in the GIV-CT-negative group and 62 ± 9% (mean ± SE, p = 6 × 10−5) in the GIV-CT-positive group. Unpaired t-test revealed that the GIV-fl-negative and GIV-fl-positive subgroups were otherwise similar with respect to mean age at diagnosis and gender ratio.13

Although downregulation of GIV's GEF function by alternative splicing appears to be an effective mechanism by which mitosis is preferentially triggered and cell migration is suppressed in tumor cells, it remains unclear how this phenotypic balance is achieved during wound healing or development. Because the alternatively spliced GIVΔCT variant could not be detected in normal epithelial cells,14 it is possible that GIV expression is regulated by other dynamic changes at transcriptional, translational or posttranslational steps that specifically affect the integrity and function of the critical C-terminal domain of GIV without affecting its N-terminus. In fact, a phylogenetic analysis of mammalian GIV provides valuable insights into the origin of its C-terminal specialized region as an independent and autonomous entity (Fig. 5). While GIV's N-terminus evolved early (homologs found in worms and flies), its C-terminus evolved much later (first seen in fish) as a separate protein. Of note, the fish protein corresponding to GIV's C-terminus contains sequence homology to the GEF motif, suggesting that the need for G protein activation via non-receptor proteins might have risen at this stage of evolution. The separate N- and C-termini in fish were coupled to each other as a part of one GIV molecule in birds. Thus, mammalian GIV evolved fairly recently with the evolution of endothems (birds and mammals) from the fusion of two different proteins that evolved and independently. Consistent with this unique pattern of evolution, GIV's N- and C-termini appear to have distinct sets of functions, supported by distinct sets of domains, regulated perhaps by autonomous transcriptional/translational and even covalent modifications at a posttranslational level. These two independently evolved domains already demonstrate a distinct array of interacting partners which could account for the striking heterogeneity in intracellular distribution and functions we observe for GIV. Noteworthy, when GIV's sequence is compared to its two closest homologs, Daple/KIAA1509 and GIPIE/FLJ00354, significant sequence similarity is found only in the N-terminal region containing the microtubule-binding HOOK domain and the long coiled-coil domain (Fig. 1), whereas the C-terminal region is highly divergent. This suggests that the C-terminal domains of these proteins have evolved independently to interact with a different set of proteins and develop unique biological functions that differentiate the members of this family from each other. In fact, the C-terminal domain of Daple/KIAA1509 was found to be involved in the regulation of Wnt signaling by interacting with Dishevelled via its C-terminal PDZ motif.44 Similarly, GIPIE/FLJ00354 has been recently reported to regulate the ER stress response by interacting with GPR78 also via its C-terminal domain.45 These findings support the view of the C-terminal domain of proteins of this family as a critical determinant of their specific functions.

Figure 5.

The C-terminus of GIV which contains the EGFR/Akt/Actin-binding and GEF domains is evolutionarily young and evolved independently from the N-terminus. The various domains of mammalian GIV are color-coded as in Figure 1A. The various domains present in GIV orthologs in different species are displayed. The N-terminus of GIV (comprised of the hook, coiled-coil and G-binding domains) evolved early and is present in worms and flies. Although unicellular organisms (yeast and amoeba) do not have a clear ortholog of GIV, two proteins (Uso1 and interaptin) share some degree of similarity. The C-terminus of GIV evolved as part of a separate protein for the first time in fish. The N- and C-termini fused together as one GIV molecule in birds. Thus, birds and mammals express full-length GIV with the highly specialized C-terminus.

GIV is a ‘molecular rheostat’ that fine-tunes signals initiated by multiple receptors via common G protein pathways.

Heterotrimeric G proteins are recognized as the major gate keepers of signal transduction between GPCRs and their intracellular effectors. When activated by GPCRs, the natural GEFs for trimeric G proteins, Gα-GTP and Gβγ in turn interact with different effectors to initiate a variety of signaling pathways (e.g., cAMP, PLC, PKC, PI3K-Akt)46 until GAPs terminate this signaling. A growing body of work by us6,7,10,14,41 and others47–51 has now established that trimeric G proteins can also transduce signaling downstream of the growth factor RTKs and that G proteins can also be activated by non canonical pathways, namely, by non-receptor/cytosolic GEFs.7,52–55 We have demonstrated that GIV grades PI3K-Akt signals initiated by both GPCRs and RTKs,6,7,10,14,41 and that this gradation of signals helps dictate key cellular phenotypes.6,7,14,41 While the combination of suppressed PI3K/Akt and enhanced c-Src and MAPK/ERK signals drive mitosis in the fed state14 or initiate autophagy when starved,41 enhancement of PI3K/Akt signals and suppression of c-Src and MAPK/ERK activities triggers migration and reversal of autophagy. Unifying themes that underlie these discoveries is that GIV can grade signals in distinct pathways irrespective of their receptor of origin and thereby dictate complex cellular phenotypes and decisions which are most often driven by multiple receptors. Our findings are in keeping with others' predictions using systems biology that it is the unique mix of variable grades of signals initiated by multiple receptors, but not their absolute intensities that determines cell fate.21 Based on our observations we propose that GIV functions as a “molecular rheostat” that fine tunes incoming signals from different classes of receptors to dictate cellular phenotype. This is specially relevant in the context of cancer, a disease of multi-receptor etiology, because dysregulation of GIV expression in epithelia gives rise to abnormal signaling programs downstream of multiple receptors, that can drive both tumor growth and invasion such that tumors which express the highest levels of this PI3K-Akt enhancer, carry the poorest prognosis and have the greatest likelihood of progressing to metastasis.13

Our definition of GIV as a rheostat is in keeping with recent advances in the understanding of signal transduction. Signaling cascades have been traditionally described as inherently switch-like: A myriad of receptors activate an overlapping set of enzyme/kinase molecules in the immediate post-receptor tier, which in turn activate other molecules in subsequent tiers like a triangular cascade of dominoes so that signals are either transduced in full or completely shut off. Such a cascade involving covalent modifications of proteins in each tier may amplify a weak signal, accelerate the speed of signaling, steepen the profile of a graded input as it is propagated, filter out noise in signal reception, introduce time delay and allow alternative entry points for differential regulation.56–60 In contrast to this view of signaling as discrete modes of all-or-none signaling via molecular switches, recent studies have uncovered two additional sources of complexity in this process. The first complexity concerns the fact that most cellular processes like migration, proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis or survival can be driven by more than one receptor or one class of receptors and most of the time requires synergistic signaling of diverse classes of receptors simultaneously in response to a single trigger.61–68 For example, both growth factor and GPCRs can trigger cell migration.69 This phenomenon by which receptors can transactivate each other at the cell-surface is referred to as receptor-crosstalk.61–68 Unrestricted signaling due to recruitment of multiple receptors via cross-talk is felt to be critical in driving many pathological processes, e.g., cancer invasion,67,70–79 fibrogenesi80–83 and inflammation.62,84–87 Thus, it appears that there might be decisive points in the cascade of signaling dominos where incoming signals from diverse groups of receptors are integrated to efficiently drive a given cellular process. The second layer of complexity stems from the fact that switch-like ‘on-and-off’ signaling undergoes further refinement into ‘graded’-signaling in a timed manner.88–95 Existence of molecules within the signal transduction cascade that introduce fine-tuned grades to receptor-initiated signals has only recently been described in yeast, the MAPK/ERK modulator, Ste5,96–100 from whence the concept of “molecular rheostats” has emerged. Ste5 can grade MAPK signaling from low to high levels, much like variable resistors regulate current flowing within an electronic circuit do to the intensity of a light bulb. Thus, unlike all-or-none mode of signaling via “switches,” rheostats enable transduction of current in a timely manner and over a certain range of intensities without any interruption. However, the identification of such rheostats in mammals, their mode of action and possible implication in disease has remained elusive to date.

Our recent work not only sheds light on the molecular mechanism that enables GIV to function as a molecular rheostat but also pinpoints its role in physiology and disease. We have unraveled that GIV's GEF function couples G protein activation to multiple ligand-activated receptors and thereby, simultaneously modulates their signaling and dictates the resultant cellular phenotype. While direct binding to ligand-activated receptors allows GIV to intercept signals at an immediate post-receptor tier, GIV's GEF motif couples cyclical activation of the G proteins in the immediate vicinity of a ligand-activated receptor. We propose that localized activation of G proteins in this niche allows for further gradation (step-wise amplification or attenuation) of incoming receptor-initiated signals in a timed manner by intermediates within the G protein pathway. Cells may additionally fine-tune such signaling via G proteins by changing the number of copies of GIV-GEF (as demonstrated in cancer cells and tumors in situ13,14), or by dynamically changing its ability to bind or activate Gi (e.g., by phosphoregulation, ubiquitination, and/or other covalent modifications, unpublished work). Such low, intermediate, or rapid-cycling states of G proteins in the vicinity of activated receptors in turn allows GIV to grade signal intensities over a broad and continuous range (much like a rheostat; Fig. 6), irrespective of the class of receptor that initiates it. Previous work has indicated that receptor-initiated signals are decisively graded at the immediate post-receptor level by mechanisms that are poorly understood to dictate cellular phenotypes.22 By demonstrating that in the absence of GIV's GEF function, gradation of receptor-initiated signals through G protein pathways does not occur,14,41 we have now defined that the GIV-rheostat performs such integration at the level of the receptor tail. Outstanding questions remain concerning whether there are other molecular rheostats that similarly grade incoming signals irrespective of the receptor of origin and whether all these rheostats have a unified modus operandi (i.e., ability to couple various Gα-proteins to different classes of receptors).

Figure 6.

Working model for how GIV serves as a molecular rheostat during tumor progression. Schematic representation (from top to bottom) of how alterations in GIV expression balances mitosis and migration during tumor progression via intermediate steps of altered activation of G proteins and modulation of signals initiated by growth factor receptors. The molecular mechanism(s) that govern each step are listed on the right. Multiple mechanisms at transcriptional, translational and post-translational levels contribute to changes in the expression of GIV, or selectively it's C-terminus in the tumor epithelium, thereby directly affecting the number (#) of functionally intact copies of GIV's GEF motif (top). As a direct consequence of this, the rate-limiting step in cyclical activation of G proteins is proportionately altered over a broad range, in-continuum, from slow-cycling state in which the G protein spends longer duration in the GDP-bound inactive state to rapid-cycling state in which the G protein spends longer duration in the GTP-bound active state. This translates into graded enhancement of PI3K activity via G protein intermediates (Gβγ) and modulation of a variety of other motogenic and mitogenic signals by coupling of G protein activation to ligand-activated EGFR. Presence or absence of GIV's GEF function results in amplification of different sets of signaling programs and thereby, triggers migration-proliferation dichotomy—In the presence of an intact GEF motif, G proteins are activated, motogenic signals are enhanced and cell migration is triggered, whereas in the absence of a functional GEF motif, G proteins remain inactive, mitogenic signals are enhanced and mitosis is triggered. Expression of full-length GIV, and thereby the number of copies of functional GEF motifs is decreased early during tumor growth and increased later during tumor invasion, influencing both tumor size and metastasis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by awards from Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and American Gastroenterology Associate to P.G., by NIH grants CA100768 and DKI7780 to M.G.F. and by a Susan G. Komen Postdoctoral fellowship KG080079 to M.G-M.

References

- 1.Le-Niculescu H, Niesman I, Fischer T, DeVries L, Farquhar MG. Identification and characterization of GIV, a novel Galpha i/s-interacting protein found on COPI, endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi transport vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22012–22020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson F, Martin S, Evans TM, Kerr M, James DE, Parton RG, et al. A novel hook-related protein family and the characterization of hook-related protein 1. Traffic. 2005;6:442–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anai M, Shojima N, Katagiri H, Ogihara T, Sakoda H, Onishi Y, et al. A novel protein kinase B (PKB)/AKT-binding protein enhances PKB kinase activity and regulates DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18525–18535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enomoto A, Murakami H, Asai N, Morone N, Watanabe T, Kawai K, et al. Akt/PKB regulates actin organization and cell motility via Girdin/APE. Dev Cell. 2005;9:389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enomoto A, Ping J, Takahashi M. Girdin, a novel actin-binding protein, and its family of proteins possess versatile functions in the Akt and Wnt signaling pathways. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1086:169–184. doi: 10.1196/annals.1377.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh P, Garcia-Marcos M, Bornheimer SJ, Farquhar MG. Activation of Galphai3 triggers cell migration via regulation of GIV. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:381–393. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Marcos M, Ghosh P, Farquhar MG. GIV is a nonreceptor GEF for Galphai with a unique motif that regulates Akt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3178–3183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900294106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang P, Enomoto A, Jijiwa M, Kato T, Hasegawa T, Ishida M, et al. An actin-binding protein Girdin regulates the motility of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1310–1318. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitamura T, Asai N, Enomoto A, Maeda K, Kato T, Ishida M, et al. Regulation of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis by the Akt/PKB substrate Girdin. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:329–337. doi: 10.1038/ncb1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Marcos M, Ghosh P, Ear J, Farquhar MG. A structural determinant that renders G alpha(i) sensitive to activation by GIV/girdin is required to promote cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12765–12777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maier U, Babich A, Nurnberg B. Roles of non-catalytic subunits in gbetagamma-induced activation of class I phosphoinositide-3-kinase isoforms beta and gamma. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29311–29317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephens L, Smrcka A, Cooke FT, Jackson TR, Sternweis PC, Hawkins PT. A novel phosphoinositide-3-kinase activity in myeloid-derived cells is activated by G protein beta gamma subunits. Cell. 1994;77:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Marcos M, Jung BH, Ear J, Cabrera B, Carethers JM, Ghosh P. Expression of GIV/Girdin, a metastasis-related protein, predicts patient survival in colon cancer. FASEB J. 2011;25:590–599. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-167304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh P, Beas AO, Bornheimer SJ, Garcia-Marcos M, Forry EP, Johannson C, et al. A Gi-GIV molecular complex binds epidermal growth factor receptor and determines whether cells migrate or proliferate. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2338–2354. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weng L, Enomoto A, Ishida-Takagishi M, Asai N, Takahashi M. Girding for migratory cues: roles of the Akt substrate Girdin in cancer progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haugh JM. Localization of receptor-mediated signal transduction pathways: the inside story. Mol Interv. 2002;2:292–307. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.5.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rijken PJ, Hage WJ, van Bergen en Henegouwen PM, Verkleij AJ, Boonstra J. Epidermal growth factor induces rapid reorganization of the actin microfilament system in human A431 cells. J Cell Sci. 1991;100:491–499. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyer AK, Tran KT, Griffith L, Wells A. Cell surface restriction of EGFR by a tenascin cytotactin-encoded EGF-like repeat is preferential for motility-related signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214:504–512. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howlin J, Rosenkvist J, Andersson T. TNK2 preserves epidermal growth factor receptor expression on the cell surface and enhances migration and invasion of human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:36. doi: 10.1186/bcr2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy JE, Padilla BE, Hasdemir B, Cottrell GS, Bunnett NW. Endosomes: a legitimate platform for the signaling train. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17615–17622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906541106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Athale C, Mansury Y, Deisboeck TS. Simulating the impact of a molecular ‘decision-process’ on cellular phenotype and multicellular patterns in brain tumors. J Theor Biol. 2005;233:469–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen P, Xie H, Sekar MC, Gupta K, Wells A. Epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated cell motility: phospholipase C activity is required, but mitogen-activated protein kinase activity is not sufficient for induced cell movement. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:847–857. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho H, Kehrl JH. Localization of Gi alpha proteins in the centrosomes and at the midbody: implication for their role in cell division. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:245–255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fedotov S, Iomin A. Migration and proliferation dichotomy in tumor-cell invasion. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98:118101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.118101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giese A, Loo MA, Tran N, Haskett D, Coons SW, Berens ME. Dichotomy of astrocytoma migration and proliferation. Int J Cancer. 1996;67:275–282. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960717)67:2<275::AID-IJC20>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonneton C, Sibarita JB, Thiery JP. Relationship between cell migration and cell cycle during the initiation of epithelial to fibroblastoid transition. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1999;43:288–295. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1999)43:4<288::AID-CM2>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung EH, Hutcheon AE, Joyce NC, Zieske JD. Synchronization of the G1/S transition in response to corneal debridement. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1952–1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaylarde PM, Sarkany I. Cell migration and DNA synthesis in organ culture of human skin. Br J Dermatol. 1975;92:375–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb03096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ausprunk DH, Folkman J. Migration and proliferation of endothelial cells in preformed and newly formed blood vessels during tumor angiogenesis. Microvasc Res. 1977;14:53–65. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(77)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerhardt H, Golding M, Fruttiger M, Ruhrberg C, Lundkvist A, Abramsson A, et al. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:1163–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandel HG, Rall DP. The present status of cancer chemotherapy—a summary of papers delivered at the Cherry Hill Conference on “a critical evaluation of cancer chemotherapy”. Cancer Res. 1969;29:2478–2485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlessinger J, Lemmon MA. SH2 and PTB domains in tyrosine kinase signaling. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:12. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.191.re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shao H, Wu C, Wells A. Phosphorylation of alpha-actinin 4 upon epidermal growth factor exposure regulates its interaction with actin. J Biol Chem. 285:2591–2600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang J, Gross DJ. Regulated EGF receptor binding to F-actin modulates receptor phosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:930–936. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becker M, Sommer A, Kratzschmar JR, Seidel H, Pohlenz HD, Fichtner I. Distinct gene expression patterns in a tamoxifen-sensitive human mammary carcinoma xenograft and its tamoxifen-resistant subline MaCa 3366/TAM. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:151–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagaraja GM, Othman M, Fox BP, Alsaber R, Pellegrino CM, Zeng Y, et al. Gene expression signatures and biomarkers of noninvasive and invasive breast cancer cells: comprehensive profiles by representational difference analysis, microarrays and proteomics. Oncogene. 2006;25:2328–2338. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stickeler E, Kittrell F, Medina D, Berget SM. Stage-specific changes in SR splicing factors and alternative splicing in mammary tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 1999;18:3574–3582. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sassen S, Miska EA, Caldas C. MicroRNA: implications for cancer. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0532-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Godlewski J, Bronisz A, Nowicki MO, Chiocca EA, Lawler S. microRNA-451: A conditional switch controlling glioma cell proliferation and migration. Cell Cycle. 9:2742–2748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia-Marcos M, Ear J, Farquhar MG, Ghosh P. A GDI (AGS3) and a GEF (GIV) regulate autophagy by balancing G protein activity and growth factor signals. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:673–686. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehrpour M, Esclatine A, Beau I, Codogno P. Autophagy in health and disease. 1. Regulation and significance of autophagy: an overview. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 298:776–785. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00507.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giese A, Bjerkvig R, Berens ME, Westphal M. Cost of migration: invasion of malignant gliomas and implications for treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1624–1636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oshita A, Kishida S, Kobayashi H, Michiue T, Asahara T, Asashima M, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel Dvl-binding protein that suppresses Wnt signalling pathway. Genes Cells. 2003;8:1005–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2003.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsushita E, Asai N, Enomoto A, Kawamoto Y, Kato T, Mii S, et al. Protective role of Gipie, a Girdin family protein, in endoplasmic reticulum stress responses in endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 22:736–747. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilman AG. G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:615–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao C, Huang X, Han Y, Wan Y, Birnbaumer L, Feng GS, et al. Galpha(i1) and Galpha(i3) are required for epidermal growth factor-mediated activation of the Akt-mTORC1 pathway. Sci Signal. 2009;2:17. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dhanasekaran DN. Transducing the signals: a G protein takes a new identity. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:31. doi: 10.1126/stke.3472006pe31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Shewy HM, Johnson KR, Lee MH, Jaffa AA, Obeid LM, Luttrell LM. Insulin-like growth factors mediate heterotrimeric G protein-dependent ERK1/2 activation by transactivating sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31399–31407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lanner MC, Raper M, Pratt WM, Rhoades RA. Heterotrimeric G proteins and the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta contribute to hypoxic proliferation of smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:412–419. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0004OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng H, Zhao D, Yang S, Datta K, Mukhopadhyay D. Heterotrimeric Galphaq/Galpha 11 proteins function upstream of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-2 (KDR) phosphorylation in vascular permeability factor/VEGF signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20738–20745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209712200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang H, Ng KH, Qian H, Siderovski DP, Chia W, Yu F. Ric-8 controls Drosophila neural progenitor asymmetric division by regulating heterotrimeric G proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1091–1098. doi: 10.1038/ncb1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas CJ, Tall GG, Adhikari A, Sprang SR. Ric-8A catalyzes guanine nucleotide exchange on G alphai1 bound to the GPR/GoLoco exchange inhibitor AGS3. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23150–23160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802422200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Afshar K, Willard FS, Colombo K, Johnston CA, McCudden CR, Siderovski DP, et al. RIC-8 is required for GPR-1/2-dependent Galpha function during asymmetric division of C. elegans embryos. Cell. 2004;119:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tall GG, Krumins AM, Gilman AG. Mammalian Ric-8A (synembryn) is a heterotrimeric Galpha protein guanine nucleotide exchange factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8356–8362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bluthgen N, Bruggeman FJ, Legewie S, Herzel H, Westerhoff HV, Kholodenko BN. Effects of sequestration on signal transduction cascades. Febs J. 2006;273:895–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ortega F, Acerenza L, Westerhoff HV, Mas F, Cascante M. Product dependence and bifunctionality compromise the ultrasensitivity of signal transduction cascades. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1170–1175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022267399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thattai M, van Oudenaarden A. Attenuation of noise in ultrasensitive signaling cascades. Biophys J. 2002;82:2943–2950. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75635-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kholodenko BN, Sauro HM. Spatio-temporal dynamics of protein modification cascades. SEB Exp Biol Ser. 2008;61:141–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sauro HM, Kholodenko BN. Quantitative analysis of signaling networks. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004;86:5–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu Z, Kobayashi K, van Dinther M, van Heiningen SH, Valdimarsdottir G, van Laar T, et al. VEGF and inhibitors of TGFbeta type-I receptor kinase synergistically promote blood-vessel formation by inducing alpha5-integrin expression. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3294–3302. doi: 10.1242/jcs.048942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Melnikova VO, Balasubramanian K, Villares GJ, Dobroff AS, Zigler M, Wang H, et al. Crosstalk between protease-activated receptor 1 and platelet-activating factor receptor regulates melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM/MUC18) expression and melanoma metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28845–28855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Godt D, Tepass U. Breaking a temporal barrier: signalling crosstalk regulates the initiation of border cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:536–538. doi: 10.1038/ncb0509-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hartmann TN, Grabovsky V, Pasvolsky R, Shulman Z, Buss EC, Spiegel A, et al. A crosstalk between intracellular CXCR7 and CXCR4 involved in rapid CXCL12-triggered integrin activation but not in chemokine-triggered motility of human T lymphocytes and CD34+ cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:1130–1140. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0208088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qiu L, Zhou C, Sun Y, Di W, Scheffler E, Healey S, et al. Crosstalk between EGFR and TrkB enhances ovarian cancer cell migration and proliferation. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:1003–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang N, Oppenheim JJ. Crosstalk between chemokines and neuronal receptors bridges immune and nervous systems. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1210–1214. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0405224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eliceiri BP. Integrin and growth factor receptor crosstalk. Circ Res. 2001;89:1104–1110. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Szabo I, Rogers TJ. Crosstalk between chemokine and opioid receptors results in downmodulation of cell migration. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;493:75–79. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47611-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Merlot S, Firtel RA. Leading the way: Directional sensing through phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase and other signaling pathways. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3471–3478. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Egloff AM, Rothstein ME, Seethala R, Siegfried JM, Grandis JR, Stabile LP. Cross-talk between estrogen receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6529–6540. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Teodorczyk M, Martin-Villalba A. Sensing invasion: Cell surface receptors driving spreading of glioblastoma. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:1–10. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ricono JM, Huang M, Barnes LA, Lau SK, Weis SM, Schlaepfer DD, et al. Specific cross-talk between epidermal growth factor receptor and integrin alphavbeta5 promotes carcinoma cell invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1383–1391. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saxena NK, Taliaferro-Smith L, Knight BB, Merlin D, Anania FA, O'Regan RM, et al. Bidirectional crosstalk between leptin and insulin-like growth factor-I signaling promotes invasion and migration of breast cancer cells via transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9712–9722. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shida D, Fang X, Kordula T, Takabe K, Lepine S, Alvarez SE, et al. Cross-talk between LPA1 and epidermal growth factor receptors mediates upregulation of sphingosine kinase 1 to promote gastric cancer cell motility and invasion. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6569–6577. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas SM, Bhola NE, Zhang Q, Contrucci SC, Wentzel AL, Freilino ML, et al. Cross-talk between G protein-coupled receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathways contributes to growth and invasion of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11831–11839. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu X, Lazenby AJ, Siegal GP. Signal transduction cross-talk during colorectal tumorigenesis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:270–274. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000213046.61941.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Even-Ram SC, Maoz M, Pokroy E, Reich R, Katz BZ, Gutwein P, et al. Tumor cell invasion is promoted by activation of protease activated receptor-1 in cooperation with the alphavbeta5 integrin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10952–10962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lauwaet T, Oliveira MJ, Mareel M, Leroy A. Molecular mechanisms of invasion by cancer cells, leukocytes and microorganisms. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:923–931. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Matsumoto K, Ziober BL, Yao CC, Kramer RH. Growth factor regulation of integrin-mediated cell motility. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1995;14:205–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00690292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bhogal RK, Stoica CM, McGaha TL, Bona CA. Molecular aspects of regulation of collagen gene expression in fibrosis. J Clin Immunol. 2005;25:592–603. doi: 10.1007/s10875-005-7827-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bissell DM. Hepatic fibrosis as wound repair: a progress report. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:295–302. doi: 10.1007/s005350050087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Novosyadlyy R, Dudas J, Pannem R, Ramadori G, Scharf JG. Crosstalk between PDGF and IGF-I receptors in rat liver myofibroblasts: implication for liver fibrogenesis. Lab Invest. 2006;86:710–723. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Uhal BD, Kim JK, Li X, Molina-Molina M. Angiotensin-TGFbeta1 crosstalk in human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: autocrine mechanisms in myofibroblasts and macrophages. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:1247–1256. doi: 10.2174/138161207780618885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Berasain C, Perugorria MJ, Latasa MU, Castillo J, Goni S, Santamaria M, et al. The epidermal growth factor receptor: a link between inflammation and liver cancer. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:713–725. doi: 10.3181/0901-MR-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McCall-Culbreath KD, Li Z, Zutter MM. Crosstalk between the alpha2beta1 integrin and c-met/HGF-R regulates innate immunity. Blood. 2008;111:3562–3570. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van der Veeken J, Oliveira S, Schiffelers RM, Storm G, van Bergen En Henegouwen PM, Roovers RC. Crosstalk between epidermal growth factor receptor- and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling: implications for cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9:748–760. doi: 10.2174/156800909789271495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vogel CF, Matsumura F. A new cross-talk between the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and RelB, a member of the NFkappaB family. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:734–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Biggar SR, Crabtree GR. Cell signaling can direct either binary or graded transcriptional responses. EMBO J. 2001;20:3167–3176. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.12.3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lachance JFB, Lomas MF, Eleiche A, Kerr PB, Nilson LA. Graded Egfr activity patterns the Drosophila eggshell independently of autocrine feedback. Development. 2009;136:2893–2902. doi: 10.1242/dev.036103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Delfini MC, Dubrulle J, Malapert P, Chal J, Pourquie O. Control of the segmentation process by graded MAPK/ERK activation in the chick embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11343–11348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502933102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Galindo MI, Bishop SA, Couso JP. Dynamic EGFR-Ras signalling in Drosophila leg development. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:1496–1508. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Guner B, Ozacar AT, Thomas JE, Karlstrom RO. Graded hedgehog and fibroblast growth factor signaling independently regulate pituitary cell fates and help establish the pars distalis and pars intermedia of the zebrafish adenohypophysis. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4435–4451. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guzman-Ayala M, Lee KL, Mavrakis KJ, Goggolidou P, Norris DP, Episkopou V. Graded Smad2/3 activation is converted directly into levels of target gene expression in embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:4268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vincent SD, Dunn NR, Hayashi S, Norris DP, Robertson EJ. Cell fate decisions within the mouse organizer are governed by graded Nodal signals. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1646–1662. doi: 10.1101/gad.1100503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xi R, McGregor JR, Harrison DA. A gradient of JAK pathway activity patterns the anterior-posterior axis of the follicular epithelium. Dev Cell. 2003;4:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Andersson J, Simpson DM, Qi M, Wang Y, Elion EA. Differential input by Ste5 scaffold and Msg5 phosphatase route a MAPK cascade to multiple outcomes. EMBO J. 2004;23:2564–2576. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Elion EA. The Ste5p scaffold. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3967–3978. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.22.3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Flatauer LJ, Zadeh SF, Bardwell L. Mitogen-activated protein kinases with distinct requirements for Ste5 scaffolding influence signaling specificity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1793–1803. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1793-1803.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Garrenton LS, Young SL, Thorner J. Function of the MAPK scaffold protein, Ste5, requires a cryptic PH domain. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1946–1958. doi: 10.1101/gad.1413706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pincet F. Membrane recruitment of scaffold proteins drives specific signaling. PLoS One. 2007;2:977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]