Abstract

Background

Surgical navigation in TKA facilitates better alignment; however, it is unclear whether improved alignment alters clinical evolution and midterm and long-term complication rates.

Questions/purposes

We determined the alignment differences between patients with standard, manual, jig-based TKAs and patients with navigation-based TKAs, and whether any differences would modify function, implant survival, and/or complications.

Patients and Materials

We retrospectively reviewed 97 patients (100 TKAs) undergoing TKAs for minimal preoperative deformities. Fifty TKAs were performed with an image-free surgical navigation system and the other 50 with a standard technique. We compared femoral angle (FA), tibial angle (TA), and femorotibial angle (FTA) and determined whether any differences altered clinical or functional scores, as measured by the Knee Society Score (KSS), or complications. Seventy-three patients (75 TKAs) had a minimum followup of 8 years (mean, 8.3 years; range, 8–9.1 years).

Results

All patients included in the surgical navigation group had a FTA between 177° and 182º. We found no differences in the KSS or implant survival between the two groups and no differences in complication rates, although more complications occurred in the standard technique group (seven compared with two in the surgical navigation group).

Conclusions

In the midterm, we found no difference in functional and clinical scores or implant survival between TKAs performed with and without the assistance of a navigation system.

Level of Evidence

Level II, therapeutic study. See the Guidelines online for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Two studies [5, 14] confirm that prosthetic component alignment in TKAs following a neutral mechanical axis (180º ± 3º) is crucial to achieve the best long-term survival. Despite the use of new tools and equipment, 10% of tibial cuts have a deviation greater than 4° [11] compared with the preplanned goal. Deviations in final prosthesis alignment are common, even when the TKAs are performed by experienced surgeons, and two articles suggest only 75% of patients achieve a neutral (180° ± 3°) femorotibial alignment [16, 18]. Computer-assisted surgery (CAS) is a potentially cost-effective addition to TKA [19]. Although it has been reported that CAS successfully reduces the number of alignment outliers, navigation requires more surgery time [13, 15], is more expensive, has a learning curve, and there is the possibility of complications and adverse effects owing to tracker fixing [8]. In a prospective study of 40 patients having TKAs, 20 were randomized to a standard, manual, jig-based technique and the other 20 were treated with CAS [9]. We found an ideal FTA (180° ± 3°) was achieved for all patients in the CAS group, but this angle was achieved in only nine patients in the standard technique group.

Advocates of CAS suggest improved placement of the implants will lead to better midterm and long-term functional and survival [23], although the literature lacks studies that confirm whether the improved radiographic alignment achieved by navigation improves patient function or the durability of TKA. Furthermore, available comparative studies of the two techniques have short followup periods (5 years at the most) and use different assessment scales. The clinical benefits thus are unclear and require definition on a larger scale.

The aims of our study were to compare (1) alignment between two groups of patients without preoperative deformities undergoing TKAs with and without surgical navigation; (2) the KSS (knee and functional scores) and implant survival; and (3) complications in the two groups.

Patients and Materials

In a randomized prospective study, we performed 100 TKAs in 97 patients (three patients had bilateral TKAs) between August 2001 and October 2002. Seventy-one TKAs were performed on 69 women and 29 were performed on 28 men. The patients had an average weight of 81 kg (range, 57–107 kg). The indications for surgery for all patients were osteoarthritis with no varus or valgus deformities greater than 10º and a body mass index (BMI) less than 30 kg/m2. In 49 patients (50 TKAs), we used the standard technique with manual alignment; in the other 48 (50 TKAs), we used a wireless image-free navigation system (Stryker Image Free Computer Navigation System, versions 1.2 and 1.3; Stryker-Leibinger, Freiburg, Germany). Patients were chosen from the surgery waiting lists and were randomly assigned (closed envelope) to one of two groups immediately preoperatively. The first 40 of these TKAs have been reported [9]. The minimum followup was 8 years (mean, 8.3 years; range, 8–9.1 years) in 73 patients with 75 TKAs. Twelve patients (12 TKAs) were excluded from the navigation group: 10 did not return for scheduled followups for unknown reasons, one patient had a periprosthetic femoral fracture at 5 years postoperative, and the other had a metastatic tibial fracture. The fractures were not related to tracker placement in these patients. In the standard technique group, 12 patients (13 TKAs) were excluded: 11 who did not return for followups for unknown reasons and one with an infection requiring two-step revision surgery. At 8 years, 73 patients (75 TKAs) were available for analysis: 36 patients (38 TKAs) from the navigated TKA group and 37 patients (37 TKAs) from the standard group. The mean BMI of these patients was 27.4 kg/m2 (range, 23.2–29.7 kg/m2), their average age was 69.6 years (range, 47–85 years; SD, 7.771), and the mean preoperative KSS, including the knee score and functional score [10] was 72 (range, 48–112). No patients were recalled specifically for this study; all data were obtained from medical records and radiographs. Our institution’s ethics committee approved this study, and all patients signed an informed consent form for participation in the study.

There were no differences between the navigation or standard technique groups regarding age, gender, weight, leg mechanical axis, and KSS (Table 1). We found no differences between groups regarding preoperative radiographic alignment. The mean preoperative FA was 89.99º (range, 79º–96º; SD, 3.844º); the mean preoperative TA was 89.97º (range, 80º–96º; SD, 3.529º); and the mean FTA was 181.11º (range, 170º–189º; SD, 5.203º). We found differences between mean operating times: 80 minutes (range, 60–91 minutes; SD, 5.16) for the standard technique group and 96 minutes (range, 85–105 minutes; SD, 3.33) for the navigation group (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Preoperative data for the patients

| Parameter | Total | Standard | Computer-assisted | p values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.6 (SD, 7.8) | 68.8 (SD, 8.5) | 70.4 (SD, 6.9) | 0.283* |

| Weight (kg) | 80.6 (SD, 15.2) | 78.4 (SD, 19.2) | 80.8 (SD, 14.9) | 0.734* |

| KSS (points) | 72.6 (SD, 7.9) | 71.34 (SD, 8.2) | 73.81 (SD, 7.6) | 0.115* |

| Preoperative FTA (degrees) | 181.1 (SD, 5.2) | 181.9 (SD, 4.5) | 180.3 (SD, 5.7) | 0.111* |

| Gender (female) | 71 | 34 | 37 | 0.508** |

* Student’s t test; **chi square test.

To achieve a power of 80% to detect differences using a bilateral Student’s t-test for two independent samples (taking into account that the significance level is 5% and assuming that the difference of KSS means between the two groups is 10 and the SD is 17.5), 50 experimental units were required for the control group and another 50 for the experimental group, for a total of 100 units in the study.

The same two surgeons (DHV, ASV) performed all operations. The implants (Interax; Stryker/Howmedica, Limerick, Ireland) and navigation system were the same for every patient. In all patients, surgeons cemented the arthroplasties and implanted prosthetic patellar implants. The surgical technique (excluding the use of navigation) and postoperative guidelines were similar. Surgeons assigned patients to either group randomly, not knowing which technique had been assigned to which patient until the time the operation started. For the group of patients undergoing the standard procedure, surgeons used intramedullary femoral and extramedullary tibial alignment guiding rods. In this group, the surgeons systematically performed attachment of the femoral component with 3º external rotation with respect to the posterior condyle line, and all femoral, tibial, and patellar cuts were made following the technical recommendations provided by the implant designers.

Postoperative guidelines were the same for both groups. Patients started knee mobilization the first day after surgery, and mobility using a cane at 2 days; suction drains were left in place for 48 hours. A standard radiograph of the knee (frontal and lateral planes) was taken the same day surgery was performed. Patients were discharged after 6 days with a previously assigned protocol and received physiotherapy at home.

During the first followup 1 month after surgery, a clinical examination was performed, knee movement was assessed, and walking without assistive devices was allowed. Patients were clinically examined again after 12 months and then annually. A standard radiograph of the knee was performed each year and at 3, 5, and 8 years. During each visit, a KSS questionnaire was filled out. This scoring system [10] combines a relatively objective knee score that is based on the clinical parameters and a functional score based on how the patient perceives that the knee functions with specific activities. The maximum knee score is 100 points and the maximum functional score is 100 points.

We obtained frontal plane CT scans of the entire limb, including the femoral head and the ankle, and long-leg films in the sagittal plane for all patients preoperatively, at 1 month after surgery, and at 8 years to verify the FA, TA, and FTA mechanical axes. The position of the implant in the sagittal plane was checked with a lateral radiograph (with the knee flexed) and the FA and TA mechanical axes were measured. In our radiographic study, we analyzed three axes: the FA (perpendicular between the articular distal femoral condyles [preoperatively] or femoral component [postoperatively] and the mechanical axis of the femur); the TA (perpendicular between the articular proximal tibia [preoperatively] or tibial platform [postoperatively] and the tibial axis); and the FTA (formed by the mechanical axes of the femur and tibia). The FA and TA revealed the quality of component frontal positioning, which, theoretically, should have formed a 90º angle with the mechanical axis of the bone segment. The FTA was the final index for placement of the implant and should have been as close to 180º as possible. Two of the authors (DHV, SIF) measured angulation in the coronal and sagittal planes. Each observer conducted three measurements of each angle preoperatively and postoperatively. These measurements then were averaged to obtain the final angulation. To facilitate gathering the data and statistical analysis, we considered varus angulation as negative and valgus angulation as positive (in this way, the angulation data were included in the information provided by the navigation system).

Complications were divided into minor and major, the latter being defined as those requiring revision surgery owing to infections or aseptic component loosening. The date of each such occurrence was recorded.

We computed descriptive statistics for all variables. To compare the mean angulation between the studied groups, we used a Student’s t-test (data were normally distributed, homogeneity of variances between groups was checked by Levene’s test). To compare the percentage of patients with neutral mechanical axis (180º ± 3º) between the two groups, a chi square test was used. We determined survival with revision surgery as the endpoint using the Kaplan-Meier method; we compared survival between groups with the log-rank test. Data were stored in a Microsoft Access database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and analyzed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA)

Results

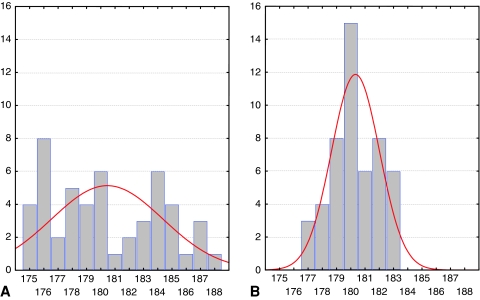

The patients in the navigated group had more ideally positioned implants (p < 0.001) than those in the standard group based on the mean coronal FA and TA (Table 2). The average immediate postoperative coronal FA of the overall series was 90.69º (SD, 1.983º), average coronal TA was 90.96º (SD, 2.449º), and average coronal FTA was 180.36º (SD, 2.980º). Mean coronal FTA differences were similar, although data scattering in the standard technique group was remarkable. The mean sagittal FA was similar in the two groups: 2º (range, 1.56º–2.54º), and the mean sagittal TA was similar: 3.5º (range, 2.81º–4.62º). All patients in the navigation group had an ideal coronal FTA (180º ± 3º) compared with 23 patients in the standard group (Fig. 1). No changes of alignment were observed during followup. At the 8-year followup, the mean coronal FA of the patients was 90.60º (SD, 1.980º), mean coronal TA was 90.83º (SD, 2.622), and mean coronal FTA was 180.13º (SD, 3.138º). At 8 years, we found no differences in the measurements for the coronal or sagittal FAs between both groups (p = 0.001), although there were differences between the coronal TA (p = 0.072) and the coronal FTA (p = 0.888).

Table 2.

Postoperative radiographic results

| Angle | Mean (º) | SD | Minimum (º) | Maximum (º) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronal FA | |||||

| Standard | 91.52 | 1.66 | 88 | 95 | <0.001 |

| Navigation | 89.86 | 1.95 | 85 | 94 | |

| Total | 90.69 | 1.98 | 85 | 95 | |

| Coronal TA | |||||

| Standard | 91.62 | 2.45 | 84 | 95 | 0.006 |

| Navigation | 90.3 | 2.29 | 84 | 99 | |

| Total | 90.96 | 2.45 | 84 | 99 | |

| Coronal FTA | |||||

| Standard | 180.42 | 3.89 | 175 | 188 | 0.842 |

| Navigation | 180.3 | 1.68 | 177 | 182 | |

| Total | 180.36 | 2.98 | 175 | 188 | |

| Sagittal FA | |||||

| Standard | 2.07 | 0.25 | 1.56 | 2.54 | 0.339 |

| Navigation | 2.02 | 0.27 | 1.51 | 2.49 | |

| Total | 2.05 | 0.26 | 1.51 | 2.54 | |

| Sagittal TA | |||||

| Standard | 3.51 | 0.56 | 2.81 | 4.57 | 0.71 |

| Navigation | 3.56 | 0.78 | 2.86 | 4.62 | |

| Total | 3.53 | 0.62 | 2.81 | 4.62 | |

* Student’s t-test; FA = femoral angle; TA = tibial angle; FTA = femorotibial angle.

Fig. 1A–B.

Case distribution by femorotibial angle (FTA) is shown for the (A) standard technique and (B) navigation technique.

We observed no differences in clinical and functional evaluation or in survival rates at 8 years. No differences (p = 0.290) were found in the KSS (knee and functional scores) between the navigation and standard groups. The mean KSS for all 73 patients (75 TKAs) at 8 years was 168 (range, 92–186). The mean was 169 points for the navigation group and 173 points for the standard group. Survival rates at 8 years were similar (p = 0.068) for the two groups: 94.74% for the navigation group and 81.08% for the standard group.

Major complications (those requiring revision surgery) were similar between groups (Table 3). In three patients in the navigation group we performed a manipulation under anesthesia 4 weeks after surgery because 90° flexion had not been attained. Another three patients in this group had mild discomfort at the tracker cut, especially in the tibia. A patient from the standard group had a deep infection 2½ years after surgery that required two-stage revision surgery.

Table 3.

Major complications in both groups

| Type of complication | Standard | Navigation | p Value (*) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infections | 2.70% | 0.00% | 0.4933 |

| Aseptic complications | 18.92% | 5.56% | 0.0824 |

| Polyethylene wear | 5.41% | 0.00% | 0.2400 |

| Tibial loosening | 5.41% | 5.56% | 0.6823 |

| Femoral loosening | 8.11% | 0.00% | 0.1150 |

* Fisher`s exact test.

Discussion

CAS allows for a higher degree of accuracy in knee arthroplasty alignment, even in knees with previous deformities [10]. Nevertheless, there literature contains no documentation on whether the radiographic improvement leads to an improvement of clinical and functional scores or implant survival in the midterm and long-term. Studies comparing TKAs performed with the standard technique and navigated TKAs have short followups (5 years at the most), and use different assessment scales (Table 4) [4, 12, 20, 21]. We made three assessments: (1) we studied the final implant alignment of both techniques by analyzing the FA, TA, and FTA by CT and standard radiographs; (2) we made an assessment based on clinical and functional scales and the survival rates; and (3) we compared the presence of complications during a minimum 8-year followup.

Table 4.

Results of comparative studies of standard technique and computer-assisted surgery

| Study | Followup (years) | Number of arthroplasties | Computer-assisted | Standard | Scores | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spencer et al. [21] | 2 | 62 | 32 | 30 | KSS | No differences |

| Oxford | ||||||

| WOMAC | ||||||

| Kamat et al. [12] | 3 | 151 | 67 | 84 | KSS | No differences |

| Oxford | ||||||

| Choong et al. [4] | 1 | 115 | 60 | 55 | IKS | Better navigation |

| SF-12 | ||||||

| Seon et al. [20] | 2 | 85 | 43 | 42 | HSS | No differences |

| WOMAC | ||||||

| Current study | 8 | 75 | 38 | 37 | KSS | No differences |

KSS = Knee Society Score; IKS = International Knee Score; HSS = Hospital for Special Surgery score; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index; SF-12 = Short Form-12.

Our study has some limitations. First, we lost some patients before the minimum 8-year followup, although the percentage is similar to those in other studies with comparable followups. To determine whether these lost patients could influence our findings and mean angulations of the remaining series, we assessed the leg axis of the remaining patients at 8 years and found similar values to those observed during the immediate postoperative study of the overall series. Second, we used an implant commonly used in Central and Southern Europe, but which is no longer commercially available. Nevertheless, as the same devices were used in both groups, this fact does not modify the comparative data found. Third, the radiographic and CT measurements were performed by two observers. Surgeons were blinded to radiographic alignment and measurements were made at three different times and the averages used; we did not compute intraobserver or interobserver variability.

Several meta-analyses review comparative studies of radiographic alignment between computer-assisted and standard TKAs. Mason et al. [17] examined 29 studies of CAS versus standard TKA. Mechanical axis malalignment greater than 3° occurred in 9.0% of CAS, compared with 31.8% of standard TKAs. Brin et al. [3] reported surgery performed with CAS reduced the rate of outliers in limb mechanical axis by approximately 80%. Bathis et al. [1] reviewed 13 studies: in the group of patients who underwent the standard technique, surgeons implanted 75% of prostheses in the safe zone (180° ± 3°), whereas in the CAS group, they implanted almost 94% of the prostheses in the safe zone. Patients who had navigated surgery had a lower risk of malalignment at critical thresholds greater than 3°, according to another meta-analysis of the findings of 11 randomized trials [2]. Novicoff et al. [19] examined 22 randomized controlled studies comparing manual and CAS techniques in TKA and showed a clear advantage of CAS over manual surgery in terms of alignment. However, they concluded there is a need for studies that examine function at more than 1 year postoperatively using standardized assessment tools, especially because malalignment is an intermediate outcome measure not causally linked in all patients with eventual implant failure. Weng et al. [23] prospectively compared CAS with standard TKAs by using a bilateral knee study model. They reported that computer navigation was associated with a much higher rate of knees in a 3º-range of the neutral mechanical axis. Choong et al. [4] also performed a randomized prospective study comparing CAS with standard surgery. CAS TKAs again were associated with a higher number of knees within a 3°-range of the neutral mechanical alignment. Thus, even though many of these CAS versus standard technique comparative studies show statistical heterogeneity, navigation contributes to a higher degree of accuracy in implant alignment. We found acceptable alignment was achieved in 46% of the patients treated with the standard technique. This figure is lower than the 50% reported by Weng et al. [23] and 61% reported by Choong et al. [4]. According to these data, the standard technique does not yield consistent alignment since it varies depending on each study. An ideal alignment was possible in all patients in whom we used CAS. Postoperative FA and TA means were better in the navigation group, although we found no differences in FTA, possibly because of the sample size. Nevertheless, it is apparent that FTA distribution was markedly different between both groups (Fig. 1).

Some studies report advantages regarding function and implant survival after TKAs with a neutral mechanical axis. Longstaff et al. [14] reported that function after TKA is better in patients with neutral mechanical alignment. It seems that a functional advantage over outliers actually exists when implants are placed within 3º of a neutral mechanical axis [4]. Few studies compare the clinical and functional evolution of TKAs with and without navigation, even in the short term [12, 20, 21], and no differences have been found. However, Choong et al. [4] observed that patients with coronal alignment within 3º of neutral alignment had higher KSS and Short-Form 12 physical scores after surgery in a randomized prospective controlled trial which compared alignment, function, and patient quality of life outcomes between patients undergoing standard and CAS TKAs. They concluded that navigated knee arthroplasties achieved greater accuracy in implant alignment, and that the difference correlated with better knee function and improved quality of life. We found similar KSS scores (knee and functional scores) in both groups at 8 years. The absence of severe alignment errors in the standard technique group may explain these findings.

In a study of more than 6000 TKAs, Fang et al. [6] reported that for overall mechanical alignment, outliers had a higher failure rate. Knees that are implanted at 3º to 7º of the coronal anatomic alignment have the lowest failure rates, whereas knees outside this range have a greater than three times higher risk of failure [6]. We also found differences in complication incidence, although, whereas in the CAS group two patients had tibial metal plateau subsidence, in the standard technique group two patients had asymmetric polyethylene wear and five had tibial and femoral component loosening. In a recent comparative study [7], revisions attributable to malalignment and instability also were more frequent in the standard group, but this was not statistically significant. Survival at 8 years was similar in both groups. Patients in our series who experienced component loosening or wear of the polyethylene plateau had FTA with varus angulation, although never greater than 4º. However, this suggests varus malalignment constitutes a threat for the arthroplasty with time. The high aseptic complication rates in our series might be related to the prosthetic model we used, which has been discontinued in favor of newer models. We cannot compare our findings with this implant owing to the limited literature available regarding this prosthesis. Premature failure of the polyethylene insert has been documented for this model; in some series, the failure rate was greater than 24% during the first 3 years postoperatively [22]. We found no differences between the groups regarding other types of complications, although three patients in the navigation group had knee stiffness. It is possible that this complication is related to the percutaneous placement of a femoral tracker and the muscular wear it entails.

The benefit of computer-assisted devices probably is the reduction in the outliers defined by postoperative malalignment greater than 3º in the tibial or femoral components, or the mechanical leg axis [5]; it also allows for a more homogeneous technique, which, at the same time, can be customized for each patient. We found no differences in functional and clinical scores or complication rates between the two groups. Although CAS allows for radiographic enhancement of arthroplasty component placement, it was not associated with functional improvement or complication rate reduction in patients with a minimum 8-year followup. Thus, CAS does not provide better functional or clinical findings in TKAs in knees without deformities in the midterm.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. M. Fernández-Carreira MD for the statistical analysis and Marino Santirso for linguistic review of the document.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Hospital St Agustin, Aviles, Spain.

References

- 1.Bäthis H, Shafizadeh S, Paffrath T, Simanski C, Grifka J, Lüring C. Are computer assisted total knee replacements more accurately placed? A meta-analysis of comparative studies [in German] Orthopade. 2006;35:1056–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00132-006-1001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauwens K, Matthes G, Wich M, Gebhard F, Hanson B, Ekkernkamp A, Stengel D. Navigated total knee replacement: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:261–269. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brin YS, Nikolaou VS, Joseph L, Zukor DJ, Antoniou J. Imageless computer assisted versus conventional total knee replacement: a Bayesian meta-analysis of 23 comparative studies. Int Orthop. 2011;35:331–339. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1008-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choong PF, Dowsey MM, Stoney JD. Does accurate anatomical alignment result in better function and quality of life? Comparing conventional and computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dattani R, Patnaik S, Kantak A, Tselentakis G. Navigation knee replacement. Int Orthop. 2009;33:7–10. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0671-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang DM, Ritter MA, Davis KE. Coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty: just how important is it? J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 suppl):39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gøthesen O, Espehaug B, Havelin L, Petursson G, Furnes O. Short-term outcome of 1,465 computer-navigated primary total knee replacements 2005–2008. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:293–300. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.575743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernández-Vaquero D, Suárez-Vázquez A. Complications of fixed infrared emitters in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasties. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernández-Vaquero D, Suárez-Vázquez A, Sandoval-García MA, Noriega-Fernández A. Computer assistance increases precision of component placement in total knee arthroplasty with articular deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1237–1241. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1175-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of The Knee Society Clinical Rating System. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;248:13–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Insall JN, Scuderi GR, Komistek RD, Math K, Dennis DA, Anderson DT. Correlation between condylar lift-off and femoral component alignment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;403:143–152. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200210000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamat YD, Aurakzai KM, Adikari AR, Matthews D, Kalairajah Y, Field RE. Does computer navigation in total knee arthroplasty improve patient outcome at midterm follow-up? Int Orthop. 2009;33:1567–1570. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0690-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YH, Kim JS, Choi Y, Kwon OR. Computer-assisted surgical navigation does not improve the alignment and orientation of the components in total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:14–19. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longstaff LM, Sloan K, Stamp N, Scaddan M, Beaver R. Good alignment after total knee arthroplasty leads to faster rehabilitation and better function. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macule-Beneyto F, Hernández-Vaquero D, Segur-Vilalta JM, Colomina-Rodríguez R, Hinarejos-Gómez P, García-Forcada I, Seral-García B. Navigation in total knee arthroplasty: a multicenter study. Int Orthop. 2006;30:536–540. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0126-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahaluxmivala J, Bankes MJ, Nicolai P, Aldam CH, Allen PW. The effect of surgeon experience on component positioning in 673 Press Fit Condylar posterior cruciate-sacrificing total knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:635–640. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.23569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason JB, Fehring TK, Estok R, Banel D, Fahrbach K. Meta-analysis of alignment outcomes in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihalko WM, Boyle J, Clark LD, Krackow KA. The variability of intramedullary alignment of the femoral component during total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novicoff WM, Saleh KJ, Mihalko WM, Wang XQ, Knaebel HP. Primary total knee arthroplasty: a comparison of computer-assisted and manual techniques. Instr Course Lect. 2010;59:109–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seon JK, Park SJ, Lee KB, Li G, Kozanek M, Song EK. Functional comparison of total knee arthroplasty performed with and without a navigation system. Int Orthop. 2009;33:987–990. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0594-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer JM, Chauhan SK, Sloan K, Taylor A, Beaver RJ. Computer navigation versus conventional total knee replacement: no difference in functional results at two years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:477–480. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B4.18094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugimoto K, Iwai M, Okahashi K, Kaneko K, Tanaka M, Takakura Y. Premature failure of the polyethylene tibial bearing surface of the Interax knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:658–663. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weng YJ, Hsu RW, Hsu WH. Comparison of computer-assisted navigation and conventional instrumentation for bilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:668–673. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]