Abstract

Background

Operative treatment of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures reportedly decreases the risk of symptomatic malunion, nonunion, and residual shoulder disability. Plating these fractures, however, may trade these complications for hardware-related problems. Low-profile anatomically precontoured plates may reduce the rates of plate prominence and hardware removal.

Questions/purposes

We compared the outcomes after precontoured and noncontoured superior plating of acute displaced midshaft clavicle fractures. Primary outcomes were rate of plate prominence, rate of hardware removal, and rate of complications. Secondary outcomes were ROM and pain and function scores.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 52 patients with 52 acute, displaced midshaft clavicle fractures treated with either noncontoured or precontoured superior clavicle plate fixation. Fourteen patients with noncontoured plates and 28 with precontoured plates were available for followup at a minimum of 1 year postoperatively. Postoperative assessment included ROM, radiographs, and subjective scores including visual analog scale for pain, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons questionnaire, and Simple Shoulder Test.

Results

Patients complained of prominent hardware in nine of 14 in the noncontoured group and nine of 28 in the precontoured group. Hardware removal rates were three of 14 in the noncontoured group and three of 28 in the precontoured group. Postoperative ROM and postoperative subjective scores were similar in the two groups.

Conclusions

Precontoured plating versus noncontoured plating of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures results in a lower rate of plate prominence in patients who do not undergo hardware removal.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Fractures of the clavicle account for 5% to 10% of all fractures, with injuries of the middle third of the clavicle accounting for 80% of these cases [22]. Even when substantially displaced, midshaft clavicle fractures were traditionally treated nonoperatively based on early studies suggesting nonunion rates of less than 1% [17, 25]. Many of these studies, however, failed to assess patient-oriented outcome measures that may have revealed residual functional deficits and dissatisfaction in those treated without surgery. More recent literature has suggested the incidence of nonunion with nonoperative treatment of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures approaches 15% or higher [10, 18, 24, 31]. Furthermore, patients with malunion or nonunion are at risk for substantial residual disability of the injured extremity [10, 14, 15, 18, 20, 29].

In recent literature, the operative treatment of clavicle fractures reportedly shows lower rates of long-term sequelae related to these injuries, specifically lowering the incidence of symptomatic malunion and nonunion and improving functional outcomes [2]. The optimal implant for clavicle fixation remains controversial. Intramedullary fixation of clavicle fractures is one surgical option supported in the literature [13, 27]. However, most intramedullary devices are smooth and lack compression at the fracture site with potential for pin migration. Newer-generation devices designed with a differential pitch may minimize these complications [27]. A recent meta-analysis reported operative management with compression plating reduced the clavicle nonunion rate from 15.1% to 2.2% [31]. Given this evidence of improved outcome with operative treatment, plate fixation of the clavicle is now widely accepted and used as a treatment modality, with a low rate of fixation failure [8, 31]. Plate fixation of the clavicle, however, presents several unique demands, including its complex bony architecture and its immediate subcutaneous location [16].

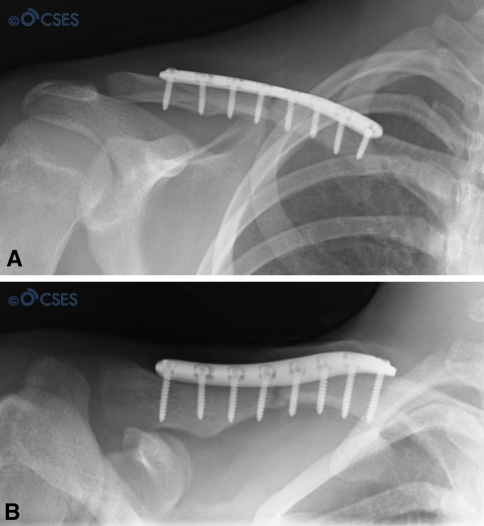

Precontoured clavicle plates have been introduced to address the challenges of clavicle fixation, with several proposed benefits (Fig. 1A). The plates are designed to fit the anatomic shape of the natural clavicle, eliminating the need for plate contouring at the time of surgery, which decreases operative time and potentially lessens the risk of plate fatigue fracture (Fig. 1B) [11]. In a study of 200 cadaveric clavicles, precontoured anatomic clavicular plates fit the curvature of the superior surface of the clavicle in a majority of patients; the plates were less conforming in white females and when placed more laterally along the clavicle [11]. In comminuted injuries, the plates may even act as a template for fracture reduction. The low profile and beveled edges of the plates are thought to reduce the incidence of postoperative hardware prominence and potentially decrease the need for reoperation and hardware removal. Finally, while strong enough to allow for early rehabilitation, the titanium composition of most precontoured plates is thought to diminish stress shielding, as its modulus of elasticity is closer to that of native bone than traditional stainless steel [30]. Biomechanically, the properties of the precontoured titanium plate are at least equivalent to those of a noncontoured plate. In a cadaveric osteotomy model, no postplating difference in axial tension, axial compression, torsional tension, and torsional compression was observed between precontoured titanium clavicle plates and 3.5-mm noncontoured plates [9]. The stiffness of the plates was also similar, leading the authors to conclude the two plates are biomechanically equivalent. In spite of anatomic and biomechanical data demonstrating precontoured plates are at least equivalent to noncontoured plates [9, 11], it is unclear whether the proposed benefits of precontoured plates are realized in a clinical setting.

Fig. 1A–B.

(A) A lateral view and (B) a superior view of the clavicle plate show precontoured plates fit the anatomic shape of the natural clavicle and are low profile with beveled edges.

We compared the outcomes after precontoured and noncontoured superior plating of acute displaced midshaft clavicle fractures. Primary outcomes were rate of plate prominence, rate of hardware removal, and rate of complications. Secondary outcomes were ROM and pain and function scores.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed all 52 patients with acutely displaced (1.5-cm shortening or greater with at least 100% cranial-caudal displacement) midshaft clavicle fractures treated with plate fixation from January 2000 to January 2009. The indications for surgery included: fractures with greater than 1.5 cm of clavicle shortening with substantially displaced fracture fragments lacking cortical apposition or impending skin compromise secondary to displaced fracture fragments. The contraindications for included: closed fractures with less than 1.5 cm of shortening with apposing fracture fragments and no evidence of impending skin compromise. None of the 52 patients sustained an open fracture nor had concomitant coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction at the time of surgery. Five patients were unwilling to participate, all of whom underwent precontoured plating, and an additional five patients, two with noncontoured and three with precontoured plates, could not be contacted. The study group therefore comprised 42 of the 52 patients (81%). The minimum followup for inclusion was 1 year. Data were obtained from medical records, radiographs, and outcome questionnaires completed at followup.

Fourteen of the study patients had noncontoured plating of the clavicle, and 28 had precontoured plating. The two groups were similar for all demographic variables (Table 1). There were no major medical comorbidities identified in the patients of either group. With the exception of one patient in the noncontoured group, all patients were nonsmokers. Two Workers Compensation patients were identified, both in the precontoured group. Mean followup was higher (p < 0.01) in the noncontoured group (7.1 years; range, 5.2–9.9 years) than in the precontoured group (3.3 years; range, 1.1–6.5 years).

Table 1.

Demographic variables

| Variable | Noncontoured | Precontoured | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 14 | 28 | |

| Age at time of surgery (years)* | 28.9 ± 8.1 (19–50) | 36.0 ± 14.6 (13–68) | 0.10 |

| Sex (male/female) | 10/4 | 22/6 | 0.61 |

| % dominant arm injury | 40% | 50% | 0.32 |

| Body mass index* | 24.0 ± 4.2 (16.7–31.6) | 24.6 ± 3.4 (18.8–33.3) | 0.63 |

* Values are expressed as mean ± SD, with range in parentheses.

An a priori power analysis to determine sample size was performed for the primary outcomes of interest including rates of plate prominence and hardware removal. Based on published studies and our clinical experience, we expected a large effect size, as classified by Cohen [5]. Chandrasenan et al. [3] reported a 60% removal of hardware rate with noncontoured plating versus 0% with precontoured plates. Reported rates of clavicle plate removal range from 0% to 76.7%, depending on the type of plate [3, 4]. We expected a 50% reduction in rate of hardware removal with precontoured plates. With an average rate of hardware removal of 45% for noncontoured plates, a 50% reduction in hardware removal with precontoured plates would result in an effect size of 0.452. For an effect size of 0.452 with p < 0.05, we determined a sample size of approximately 39 patients would provide adequate power (α > 0.80). Power analysis was performed with PASS software (NCSS, Kaysville, UT).

The mean (± SD) time from injury to surgery was 8.2 ± 6.7 days in the noncontoured group and 12.5 ± 8.8 days in the contoured group (p = 0.12). The most common mechanisms of injury were fall (19), sports-related injury (17), and motor vehicle trauma (six). All fractures were at the midshaft of the clavicle, with the majority either comminuted (25) and/or with a displaced or butterfly fragment present (20).

Plates used in the noncontoured group included a 3.5-mm Dynamic Compression Plate (DCP) (Synthes, Inc, West Chester, PA) in four patients, the 3.5-mm Locking Compression Plate (LCP) (Synthes) in two, a 3.5-mm Limited Contact Dynamic Compression Plate (LC-DCP) (Synthes) in four, and a 3.5-mm reconstruction plate in four. In the precontoured group, the Locking Clavicle Plate (Acumed, Hillsboro, OR) was used in all 28 cases. All plates were placed in a superior position on the clavicle. No intraoperative complications were reported in any patient.

Postoperatively, the affected extremity was immobilized in a sling for 2 weeks. During this time, the sling was removed at least four times a day for active ROM of the elbow and pendulum exercises of the shoulder. At 2 weeks, the patient was evaluated by the treating physician, the wound assessed, and new clavicle radiographs evaluated. Between Weeks 2 and 6, the patient received supervised physical therapy limited to passive ROM of the shoulder and active ROM of the elbow. Patients returned for repeat radiographs, wound inspection, and shoulder ROM assessment at 6 weeks. Active ROM and active assisted ROM of the shoulder occurred between Weeks 6 and 12 postoperatively. At 12 weeks, wound healing, shoulder ROM, and radiographic evidence of fracture healing were again documented by the treating physician. Progressive strengthening exercises were started at 12 weeks if the patient achieved full ROM and there was clinical and radiographic evidence of healing. The patient was evaluated again at 1 year or earlier if any issues arose.

We retrospectively reviewed the charts of the 42 study group patients for demographic and injury information. Preoperative radiographs were analyzed to determine the fracture pattern (including comminution and cranial-caudal displacement) and amount of preoperative fracture shortening. Postoperative ROM was assessed by the performing surgeon at the last office visit. Additionally, radiographic fracture healing and complications (plate prominence, wound infection, adhesive capsulitis, fracture nonunion, refracture after hardware removal) were recorded. A complication was further defined as hardware-related when it was hardware prominence or failure. Patients were contacted by mail and by telephone at the time of the study to complete outcome questionnaires including visual analog scale (VAS) pain score [28], American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) questionnaire [23], and Simple Shoulder Test (SST) [7]. The date of questionnaire completion was documented as the date of followup. Thorough review of patient records enabled complete data collection, resulting in no missing data.

Descriptive statistics, including measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables and frequency counts for categorical variables, were calculated for all variables. Comparisons between the two study groups (noncontoured versus precontoured plating) for the primary outcomes (rate of plate prominence, rate of hardware removal, and rate of complications) were performed using Fisher’s exact test. Comparisons between the two groups for the SF-36, ASES, SST, and VAS scores and ROM were performed using a two-tailed unpaired t test. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS® software (Version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Prominent hardware was reported postoperatively in nine of 14 patients (64.3%) of the noncontoured group and nine of 28 patients (32.1%) of the precontoured group (p = 0.05) (Table 2). Three of 14 (21.4%) of the noncontoured patients and three of 28 (10.7%) of the precontoured patients ultimately underwent elective removal of hardware for plate prominence (p = 0.22). The noncontoured plates removed included one DCP, one LC-DCP, and one 3.5-mm reconstruction plate. The mean time to hardware removal was similar (p = 0.18) in the noncontoured group (23.8 ± 5.0 months; range, 20.6–29.7 months) and precontoured group (17.2 ± 5.1 months; range, 11.4–21.3 months).

Table 2.

Hardware-related complications

| Complication | Noncontoured | Precontoured | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prominent hardware | 64.3% | 32.1% | 0.05 |

| Removal of hardware | 21.4% | 10.7% | 0.22 |

| Time to removal (months)* | 23.8 ± 5.0 | 17.2 ± 5.1 | 0.18 |

* Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

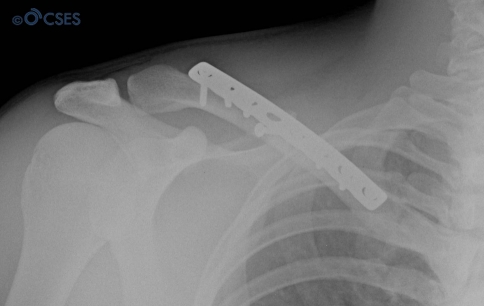

Overall complication rates (including plate prominence) were similar (p = 0.13) in the noncontoured (nine of 14, 64.3%) and precontoured groups (11 of 28, 39.3%) (Fig. 2). Excluding plate prominence, these rates similarly decreased to 0% (none of 14) and 14.3% (four of 28), respectively (p = 0.28). In the noncontoured group, plate prominence was the only postoperative complication reported (Fig. 3). In the precontoured group, there were four additional complications, including one patient with adhesive capsulitis successfully managed nonoperatively, one wound infection requiring operative débridement, and one nonunion requiring revision internal fixation with bone grafting. There was also one case of clavicle refracture in a patient after hardware removal; the plate had been removed at 11.4 months after the initial surgery. Excluding patients who underwent removal of hardware, the overall revision rate was not different (p = 0.53) for the two groups, at 0% in the noncontoured group and 10.7% (three of 28) in the precontoured group.

Fig. 2.

Plate prominence after clavicle fixation with a noncontoured plate is evident in this patient.

Fig. 3.

A noncontoured clavicle plate fixed to the superior clavicle in a subcutaneous location is shown.

In the study group as a whole, there was no difference (p = 0.72) in the mean body mass index (BMI) between patients with prominent hardware (24.2) and those without prominent hardware (24.6). Within the noncontoured group alone, there was no difference (p = 0.88) in BMI between those patients with (23.9) and without (24.2) prominent hardware. This was also true in the precontoured group, with a mean BMI of 24.4 and 24.7 in those with and without prominent hardware, respectively (p = 0.86). In the study group as a whole, sex did not influence the likelihood of postoperative plate prominence. Five of 10 female patients (50%) and 13 of 32 male patients (40.6%) complained of plate prominence (p = 0.27).

There was no difference in any parameter for postoperative ROM between the two groups (Table 3). There was also no difference between groups in postoperative VAS, ASES, or SST scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Postoperative ROM and outcome scores

| Parameter | Noncontoured | Precontoured | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active ROM | |||

| Forward elevation* | 179.6° ± 1.3° | 177.7° ± 6.9° | 0.30 |

| External rotation* | 63.6° ± 7.4° | 66.3° ± 11.0° | 0.42 |

| Internal rotation | T9 | T9 | 0.38 |

| Functional scores | |||

| VAS | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.23 |

| ASES | 98.3 | 94.0 | 0.14 |

| SST | 11.6 | 11.2 | 0.28 |

* Values are expressed as mean ± SD; VAS = visual analog scale for pain; ASES = American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons questionnaire; SST = Simple Shoulder Test.

Discussion

Although many patients can still be successfully managed nonoperatively [18], the current literature has highlighted specific clavicle fracture types that may benefit from operative intervention to avoid malunion or nonunion and their potential long-term sequelae [10, 14, 15, 19, 20, 29]. A prospective randomized study of nonoperative treatment versus plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures demonstrated better functional outcomes, a lower incidence of symptomatic malunion, and a lower rate of nonunion after plate fixation [2]. Low-profile precontoured plates that anatomically fit the superior clavicle may reduce the rate of hardware prominence and hardware removal. Anatomic and biomechanical studies demonstrated precontoured plates are at least equivalent to noncontoured plates [9, 11]. However, few published data exist determining the clinical utility of the precontoured clavicle plate or comparing clinical outcomes after precontoured and noncontoured plating [9, 11]. We therefore compared the complications, especially hardware-related problems, and patient ROM, pain, and function after precontoured and noncontoured plating of the clavicle.

There are several limitations to our study. First, it is retrospective in nature. We relied on patient records in collecting the data for the study variables. Although records for each patient were complete, there is a possibility that minor complications may have been missed at widely separated followup visits. Second, our mean followup was higher in the noncontoured group (7.1 years) than in the precontoured group (3.3 years). This is expected given that the precontoured plates were more recently introduced. Third, the size of our study was also limited because of the low frequency of noncontoured clavicle plating at our institution over the past 10 years. Because of the small numbers, our study may have lacked the statistical power necessary to detect differences in certain variables between the two groups, committing a Type II error. Fourth, all plates were placed superiorly on the clavicle. Complications related to plate prominence become less relevant when discussing anteroinferior plating that places the hardware in a less subcutaneous location [6]. Thus, our findings cannot be generalized to clavicle plating in other locations. Fifth, the heterogeneity of the plates in the noncontoured group and the low frequency of their individual utilization make it impossible to determine superiority of a specific type of noncontoured plate when compared to the others and to precontoured plates.

Whether noncontoured or precontoured plates are selected for use in internal fixation, the rate of hardware-related complications remains high [2, 21, 26]. Few published data exist on the clinical efficacy of the precontoured clavicle plate (Table 4). A recent abstract retrospectively analyzed 30 patients with plating for displaced midshaft clavicle fractures, 15 with noncontoured plating and 15 with precontoured plating [3]. At a mean of 18 months postoperatively, no patients in the precontoured group had undergone removal of hardware. In the noncontoured group, nine patients (60%) had removal of their plate: two for plate breakage, five for soft tissue irritation, and two for painful nonunion. The authors concluded there were fewer complications and a lower need for plate removal in the precontoured group. Our results demonstrate a high rate (64.3%) of hardware prominence in the noncontoured group, but a lower rate of hardware removal (21.4%) than that reported in the published abstract. The abstract authors did, however, include acute fractures, as well as nonunions and malunions, in their analysis, which may have biased their results toward a less favorable outcome; in contrast, our study only included acute midshaft fractures of the clavicle.

Table 4.

Comparison of clinical outcomes reported for plating of midshaft clavicle fractures

| Study | Plate(s) used* | Fracture type | Rate of plate prominence | Removal of hardware rate | Reoperation rate (%) | Overall complication rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kabak et al. [12] | DCP (16) LC-DCP (17) |

Nonunions | 8/16 (50%) 1/17 (5.9%) |

|||

| Chandrasenan et al. [3] | Precontoured (15) DCP or Recon (15) |

Acute, nonunions, malunions | 0/15 9/15 (60%)† |

16.7 | ||

| Bostman et al. [1] | DCP (55) One-third tubular (2) Recon (46) |

Acute | 14 | 23 | ||

| Chen et al. [4] | Semitubular (111) | Acute | 82/107 (76.7%) | |||

| VanBeek et al. | Precontoured (28) Noncontoured (14) DCP (4) LCP (2) LC-DCP (4) Recon (4) |

Acute | 9/28 (32.1%) 9/14 (64.3%) |

3/28 (10.7%) 3/14 (21.4%) |

10.7‡ 0‡ |

14.3 0 |

* Plates included: Dynamic Compression Plate (DCP) (Synthes, Inc, West Chester, PA); Limited Contact Dynamic Compression Plate (LC-DCP) (Synthes); Locking Compression Plate (LCP) (Synthes); Recon = reconstruction plate; †removal of hardware for plate breakage (two), soft tissue irritation (five), painful nonunion (two); ‡excluding hardware removal.

In our series, prominent hardware was reported in nine of 14 (64.3%) noncontoured patients and nine of 28 (32.1%) precontoured patients, suggesting double the rate of hardware-related complications may be expected with noncontoured plating. Although lower than the rates in some previously published studies [4, 12], our overall reoperation rate for hardware removal also remained relatively high (21.4% and 10.7% in the noncontoured and precontoured groups, respectively).

Our overall complication rates were consistent with or lower than rates previously published in the literature [1, 2, 21]. In an analysis of postoperative complications after clavicle fixation, Bostman et al. [1] reported an overall 23% rate of postoperative complications, with a 14% rate of reoperation. Higher complication rates were noted in severely comminuted injuries. The Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society [2] recently reported an overall complication rate of 17.7% with operative fixation in their prospective randomized clinical trial of nonoperative versus operative intervention. Excluding hardware removal, the reoperation rate in our series was 0% in the noncontoured group and 10.7% in the precontoured group. We demonstrated an overall 0% and 14.3% rate of postoperative complications in the noncontoured and precontoured groups, respectively. Given the smaller number of patients in the noncontoured group, statistically we are unable to determine from the present study whether an actual increased rate of complications is experienced in patients with precontoured plating.

In conclusion, the treatment of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures with either noncontoured or precontoured plating offers a return to baseline shoulder function, a high fracture union rate, and a low complication rate. Although future investigation will be needed to determine the cost-effectiveness of the precontoured plate, our data suggest a decrease in hardware-related complications can be expected with the use of this device in the management of displaced clavicle fractures. Specifically, precontoured plating decreases postoperative hardware prominence.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Bostman O, Manninen M, Pihlajamaki H. Complications of plate fixation in fresh displaced midclavicular fractures. J Trauma. 1997;43:778–783. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199711000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society Nonoperative treatment compared with plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1–10. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandrasenan J, Espag M, Dias R, Clark DI. The use of anatomic pre-contoured plates in the treatment of mid-shaft clavicle fractures. Injury Extra. 2008;39:171. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.11.326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CH, Chen JC, Wang C, Tien YC, Chang JK, Hung SH. Semitubular plates for acutely displaced midclavicular fractures: a retrospective study of 111 patients followed for 2.5 to 6 years. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:463–466. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31817996fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collinge C, Devinney S, Herscovici D, DiPasquale T, Sanders R. Anterior-inferior plate fixation of middle-third fractures and nonunions of the clavicle. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:680–686. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000249434.57571.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godfrey J, Hamman R, Lowenstein S, Briggs K, Kocher M. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Simple Shoulder Test: psychometric properties by age and injury type. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golish SR, Oliviero JA, Francke EI, Miller MD. A biomechanical study of plate versus intramedullary devices for midshaft clavicle fixation. J Orthop Surg Res. 2008;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goswami T, Markert RJ, Anderson CG, Sundaram SS, Crosby LA. Biomechanical evaluation of a pre-contoured clavicle plate. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:815–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill JM, McGuire MH, Crosby LA. Closed treatment of displaced middle-third fractures of the clavicle gives poor results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:537–539. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B4.7529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang JI, Toogood P, Chen MR, Wilber JH, Cooperman DR. Clavicular anatomy and the applicability of precontoured plates. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2260–2265. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabak S, Halici M, Tuncel M, Avsarogullari L, Karaoglu S. Treatment of midclavicular nonunion: comparison of dynamic compression plating and low-contact dynamic compression plating techniques. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HG. Treatment of fracture of the clavicle by internal nail fixation. N Engl J Med. 1946;234:222–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194602142340703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKee MD, Pedersen EM, Jones C, Stephen DJ, Kreder HJ, Schemitsch EH, Wild LM, Potter J. Deficits following nonoperative treatment of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:35–40. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKee MD, Wild LM, Schemitsch EH. Midshaft malunions of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:790–797. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullaji AB, Jupiter JB. Low-contact dynamic compression plating of the clavicle. Injury. 1994;25:41–45. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(94)90183-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neer CS., 2nd Nonunion of the clavicle. J Am Med Assoc. 1960;172:1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020100014003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nordqvist A, Petersson CJ, Redlund-Johnell I. Mid-clavicle fractures in adults: end result study after conservative treatment. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:572–576. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199811000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowak J, Holgersson M, Larsson S. Can we predict long-term sequelae after fractures of the clavicle based on initial findings? A prospective study with nine to ten years of follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowak J, Holgersson M, Larsson S. Sequelae from clavicular fractures are common: a prospective study of 222 patients. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:496–502. doi: 10.1080/17453670510041475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poigenfurst J, Rappold G, Fischer W. Plating of fresh clavicular fractures: results of 122 operations. Injury. 1992;23:237–241. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(05)80006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Postacchini F, Gumina S, Santis P, Albo F. Epidemiology of clavicle fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:452–456. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.126613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards RR, An KN, Bigliani LU, Friedman RJ, Gartsman GM, Gristina AG, Iannotti JP, Mow VC, Sidles JA, Zuckerman JD. A standardized method for the assessment of shoulder function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3:347–352. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Wakefield AE. Estimating the risk of nonunion following nonoperative treatment of a clavicular fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1359–1365. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowe CR. An atlas of anatomy and treatment of midclavicular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;58:29–42. doi: 10.1097/00003086-196805000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen WJ, Liu TJ, Shen YS. Plate fixation of fresh displaced midshaft clavicle fractures. Injury. 1999;30:497–500. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(99)00140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thyagarajan D, Day M, Dent C, Williams R, Evans R. Treatment of mid-shaft clavicle fractures: a comparative study. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2009;3:23–27. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.57895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wewers ME, Lowe NK. A critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13:227–236. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wick M, Muller EJ, Kollig E, Muhr G. Midshaft fractures of the clavicle with a shortening of more than 2 cm predispose to nonunion. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:207–211. doi: 10.1007/s004020000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woo SL, Lothringer KS, Akeson WH, Coutts RD, Woo YK, Simon BR, Gomez MA. Less rigid internal fixation plates: historical perspectives and new concepts. J Orthop Res. 1984;1:431–449. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100010412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zlowodzki M, Zelle BA, Cole PA, Jeray K, McKee MD. Treatment of acute midshaft clavicle fractures: systematic review of 2144 fractures: on behalf of the Evidence-Based Orthopaedic Trauma Working Group. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:504–507. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000172287.44278.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]