Abstract

Recent results from several laboratories have confirmed that human and yeast leucyl- and valyl-tRNA synthetases can rescue the respiratory defects due to mutations in mitochondrial tRNA genes. In this report we show that this effect cannot be ascribed to the catalytic activity per se and that isolated domains of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and even short peptides thereof have suppressing effects.

Abbreviations: aaRS, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase(s); bp, base-pair; MELAS, Mitochondrial Encephalomyophathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Stroke-like episodes; mt, mitochondrial; nt, nucleotide; rho+, mt DNA wild-type; WT, wild-type

Keywords: Mitochondrial diseases, tRNAs, mt mutations

Highlights

► We studied the rescuing of human equivalent yeast mutants in mttRNALeu, Val and Ile. ► Thecarboxy-terminal of human and yeast mtleuRShas full suppressing activity. ► The overexpressed human C-terminal domain isfound to be localizedin mitochondria. ► Smaller peptides from C-terminal maintain rescuing capability. ► Suppression of defective phenotypes could be due to an RNA stabilizing capability.

1. Introduction

Human mitochondrial (mt) diseases are a group of disorders due to mutations in nuclear or mt genes affecting mitochondrial functions.

A large proportion of these diseases is due to mutations in mt tRNA genes, resulting in the inhibition of mt protein synthesis and consequent OXPHOS defects, which can have variable severity, and for which at present no treatments exist. This absence is partly due to the scarcity of suitable models and to the fact that it is generally impossible to obtain site specific mitochondrial mutations. This difficulty has been overcome in yeast, in which biolistic mitochondrial transformation is possible (Bonnefoy and Fox, 2007; Fox et al., 1991).

Some years ago, we have established a yeast model of mitochondrial defects by introducing into yeast mt tRNA genes several base substitutions equivalent to those causing diseases in humans, and have observed that the consequent respiratory defects could be alleviated by overexpression of nuclearly encoded protein synthesis factors such as the mt protein elongation factor EF-Tu and the mt aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRS) (De Luca et al., 2006; De Luca et al., 2009; Feuermann et al., 2003; Montanari et al., 2008; Montanari et al., 2010).

Furthermore, we found that the same suppression of yeast defects could be obtained by the overexpression of the orthologous human factors (Montanari et al., 2010).

Moreover, nuclear factors orthologous to those we had identified in yeast were found to have suppressing activity in patient cell lines and cybrids (Li and Guan, 2010; Park et al., 2008; Rorbach et al., 2008; Sasarman et al., 2008).

AaRS are evolutionarily important enzymes on which the fidelity of protein synthesis is based; to distinguish similar aminoacids some of them have editing domains which allow misacylation to be avoided; these and the other domains involved in aminoacylation and aminoacyl-adenylate formation have been extensively studied (Hsu et al., 2006; Hsu and Martinis, 2008; Tukalo et al., 2005). In fungi, some aaRS domains also have a splicing function on mt introns (Herbert et al., 1988; Paukstelis and Lambowitz, 2008).

Another important observation was that a point mutation in mt LeuRS strongly reducing the catalytic activity did not impair the suppression capability (De Luca et al., 2009). Therefore we hypothesized that the suppressing function of aaRS might be exerted by protein regions involved in the interaction with tRNA, which might restore the correct structure of tRNA altered by the mutation in a sort of chaperon-like effect.

Isolated aaRS domains were subcloned in multicopy yeast vectors which were introduced into yeast mt tRNA mutants and examined for suppression capability.

We report here that the carboxy-terminal (C-terminal) region of human and yeast mt LeuRS has full suppressing activity. This domain is 66 (yeast) or 67 (human) aminoacids in length, so we investigated whether reduced peptides could maintain suppressing activities and hence possible therapeutic applications may be envisaged.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains, media and growth conditions

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used are the WT MCC123 (MAT a, ade2, ura3-52, Δleu, kar1-1, KanR, rho+) (Mulero and Fox, 1993) and the isogenic syn− mt mutants LeuC25T, ValC25T (bearing the same substitution in tRNALeu and tRNAVal respectively), IleT32C and IleT33C (Feuermann et al., 2003; De Luca et al., 2009; Montanari et al., 2010, and unpublished results). The IleT33C mutant showed no defective phenotype when mutated mitochondria were associated with the MCC123 nuclear context. Therefore we utilized a spore derivative showing a thermosensitive glycerol growth defect and the experiments were performed at the non permissive temperature.

The mutant strains were named with a three-letter code name of the aminoacid indicating the tRNA gene and the position of the base substitution referring to yeast cytoplasmic tRNAPhe (Sprinzl and Vassilenko, 2005). The mutants were obtained by biolistic transformation: the required mutations in tRNA genes were created by site-directed mutagenesis following the procedure described in Rohou et al. (2000) and details can be found in Feuermann et al. (2003) supplementary information.

Standard protocols (Sambrook et al., 1989) were used for E. coli and yeast transformations as well as plasmid preparations (see Supplementary material for details).

Strains were grown in YP complete medium (1% yeast extract and 1% peptone from Difco) containing 3% glycerol or glucose (2% or 0.25%). To induce the Gal1 promoter in the suppression experiments, 0.1% galactose was added to YP 3% glycerol plates. Minimal medium was 0.7% yeast nitrogen base (Difco), 5% ammonium sulphate and 2% glucose, supplemented with the necessary auxotrophic requirements. For solid plates, 1.5% agar (Difco) was added to the aforementioned media.

2.2. Microscopy

GFP plasmids were used to observe the specific cellular localization of mt LeuRS and its variants. After transformation, the selected GFP clones were grown in 2% galactose supplemented with adenine (45 µg/ml). The late exponential culture was washed in YP liquid complete medium and the pellet suspended in growth media. One aliquot was fixed on glass slide and observed by fluorescent microscopy; another aliquot was treated with 1% formaldehyde for DAPI staining to control colocalization.

3. Results and discussion

We have previously used the biolistical methodology to introduce several human equivalent base substitutions into yeast mt tRNA genes. In particular we introduced mutations into tRNALeu UUR at positions: 14, 25, 60 (MELAS equivalent), 20 (MM/CPEO equivalent) and 29 (MMC equivalent). Mutations were also introduced into tRNAVal at position 25, equivalent to the homoplasmic m. 1624 human mutation causing a syndrome with variable penetrance in the members of the same family (McFarland et al., 2002) and in tRNAIle at positions 32 and 33 equivalent to human homoplasmic mutations m. 4090 and m. 4091 reported by Limongelli et al., 2004 and by Wilson et al., 2004 respectively.

In all these mutants we have found respiratory defects mirrored by the inability to grow on respiratory carbon sources. In most cases, the severity of defects paralleled that of the corresponding human diseases. The extent of respiratory defects was also studied by oxygen consumption and by northern blot analysis of charged and uncharged tRNAs; mt protein synthesis products were also analyzed by gel electrophoresis (Montanari et al., 2010).

From the whole of these results a rather clear picture emerged concerning the defects of the various mutants; we also could demonstrate that the nuclear genetic context strongly influenced the phenotypes.

The severity of defects was relieved by the overexpression of EF-Tu (Feuermann et al., 2003) and of the cognate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (De Luca et al., 2006). Recently, we have demonstrated that suppression also took place when non-cognate aaRS as well as orthologous human enzymes were overexpressed (Montanari et al., 2010). Until now, we have limited our observations to the three mt aaRS, specific for the similar aminoacids leucine, valine and isoleucine, because we are interested in maximizing the similarities which could shed light on the conserved domains that might be involved in suppression.

Yeast mt leucyl-RS (coded by the NAM2 gene) has been the object of extensive structural studies (Hsu et al., 2006; Tukalo et al., 2005) and the specific function of each domain has been thoroughly analyzed. We could therefore examine the suppressing effect of the multicopy plasmids bearing sequences encoding isolated domains or deleted versions of yeast or human mt LeuRS. Suppression experiments were always performed with all the mentioned mutants and we obtained similar results.

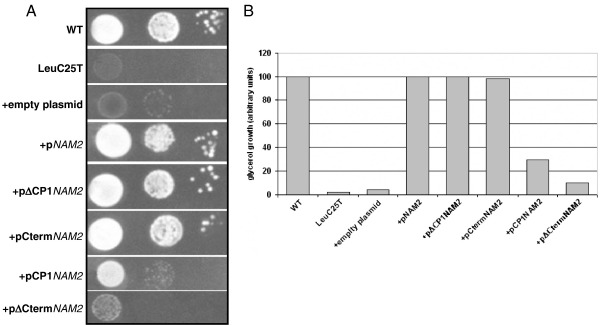

Fig. 1 shows that for mutant LeuC25T the best suppressing activity, similar to that obtained with the complete sequence of the LeuRS gene, is obtained with plasmids containing the carboxy-terminal domain (pΔCP1NAM2 and CtermNAM2).

Fig. 1.

Suppressive effect of the overexpression of NAM2 and its variants. (A) Serial dilutions of WT (MCC123), of the isogenic LeuC25T mutant and of the same mutant transformed with multicopy empty plasmid and multicopy plasmids bearing the WT NAM2 gene (coding for Sc mt leucyl-tRNA synthetase) or its different variants obtained by deletion or isolation of individual domains as indicated. The tested domains are the CP1 (Connecting Peptide 1 having editing function) and the C-terminal domains. All strains were spotted on YP plate containing 3% glycerol and incubated at 28 °C. The same results were obtained at 37 °C. (B) Graphic representation of the results shown in panel A. Values obtained by Phoretix analysis are calculated as percentage of the WT.

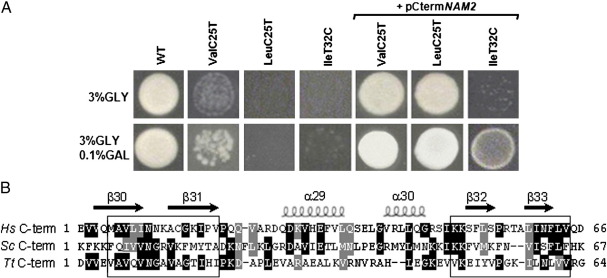

Moreover Fig. 2 (panel A) shows that the C-terminal domain of mt LeuRS can suppress the respiratory defects of some other yeast mutants in tRNAVal and tRNAIle. For the IleT32C mutant having the most defective phenotype, the suppression was only obtained when overexpression of the C-terminal domain was induced by galactose.

Fig. 2.

Suppressive effect of the CtermNAM2 domain. (A) Growth phenotype of the WT (MCC123), of isogenic mt tRNA mutants (Val, Leu and Ile), and of the same mutants transformed with the C-terminal domain of LeuRS sequence cloned into the multicopy vector (pCtermNAM2) under the inducible GAL1 promoter. The strains were plated on YP 3% glycerol and YP 3% glycerol with addition of 0.1% galactose containing media and grown for three days at 28 °C. (B) Multiple sequence alignment of the C-terminal domain of mt LeuRS (H. sapiens, Hs, S. cerevisiae, Sc, and T. thermophilus, Tt). Identical aminoacids are highlighted in black; the aminoacids with similar charge are highlighted in gray. The secondary structure elements are indicated by helices (α-helices) and arrows (β-strands). Subcloned sequences contacting the tRNA elbow (http://www.expasy.org/spbdv/) are boxed.

We then tried to reduce the size of the C-terminal sequence to test whether shorter sequences could maintain the suppressing effect. Fig. 2, panel B, shows the alignment of human and S. cerevisiae mt LeuRS together with the orthologous Thermus thermophilus sequence (used for structural studies). Boxes indicate the human LeuRS β-strand sequences contacting the tRNA elbow (www.expasy.org/spbdv/) which we have subcloned in multicopy plasmids.

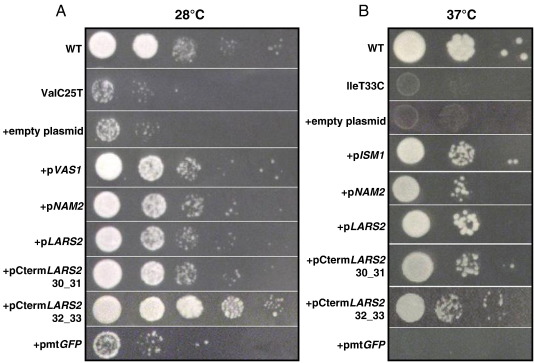

As indicated in Fig. 3, the 30_31 and 32_33 fragments from human mt LeuRS had suppressing activity similar to that obtained with the three entire synthetases (Leu-, Val- and IleRS) in relieving the glycerol growth defects of tRNAVal (panel A). The same results were obtained for LeuT25C mutant (not shown) and at 37 °C for the thermosensitive IleT33C mutant (panel B).

Fig. 3.

Suppressive effect of aaRS and parts thereof. (A) Serial dilutions of WT (MCC123), of the isogenic ValC25T mutant, of the mutant transformed with multicopy empty plasmid and multicopy plasmids bearing the VAS1 gene (coding for Sc mt ValRS), the NAM2 gene (coding for Sc mt LeuRS), the LARS2 gene (coding for Hs mt LeuRS), two CtermLARS2 variants (30_31 and 32_33) and the GFP gene fused to the mt pre-sequence of ATPase subunit 9 of Neurospora crassa (pmtGFP), as control. The strains are spotted on a YP plate containing 3% glycerol and incubated at 28 °C for three days. The same results were obtained at 37 °C. (B) Serial dilutions of the WT (MCC123), of the thermosensitive IleT33C mutant, of the same mutant transformed with multicopy empty plasmid or multicopy plasmids bearing ISM1 gene (coding for the Sc mt Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase), and other sequences as in panel A were spotted on YP plate containing 3% glycerol and incubated at 37 °C for three days.

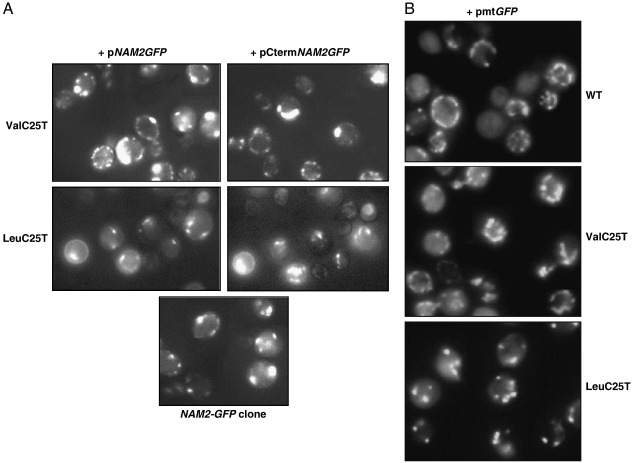

The mt localization of proteins encoded in plasmids was controlled by adding the sequence coding for green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the 3′ end of the suppressing sequence and examining cells by fluorescence microscopy. The mt localization of the isolated C-terminal domain shown in Fig. 4 (panel A), might be considered somewhat surprising due to the absence of an mt pre-sequence. However about one half of the over thousand mt nuclearly encoded proteins have been reported to lack a classical import mt pre-sequence (Bolender et al., 2008). On the other side the result of fluorescence microscopy reported in Fig. 4 B shows that similar images can be obtained with the plasmid containing the GFP protein targeted with an mt pre-sequence (Westermann and Neupert, 2000).

Fig. 4.

Cellular localization of LeuRS and its variants. (A) Fluorescence microscopy of ValC25T (upper panels) and LeuC25T (lower panels) mutants transformed with pNAM2GFP and pCtermNAM2GFP. The GFP gene sequence was cloned in frame at the 3′-end of NAM2 sequences. As control (bottom panel) the GFP YEAST CLONE (Invitrogen) with the endogenous NAM2-GFP fusion. (B) Fluorescence microscopy of WT (MCC123), ValC25T and LeuC25T transformed with a multicopy plasmid bearing the GFP gene with the mt pre-sequence of ATPase subunit 9 of N. crassa fused at 5′-end (pmtGFP).

In order to rule out the possibility that any high amount of imported protein might have suppressing effect, the aforementioned transformed mutants were also controlled for the glycerol growth phenotype. Results, shown in Fig. 3 (+ pmtGFP) clearly demonstrate that the defective growth phenotypes of mutants ValC25T and IleT33C are not rescued.

The suppression effects obtained with the isolated C-terminal domain of LeuRS and with the 30_31 and 32_33 peptides compellingly demonstrate that catalytic function is not necessary for suppression.

Therefore the increased aminoacylation of tRNALeu in cybrids containing the 3243 MELAS mutation recently observed by Li and Guan (2010) in the presence of the entire mt Lars2 is probably related to the facilitation and stabilization of the correct tRNA folding rather than to increased catalytic activity. By the way this possibility has been proposed by these authors as an alternative explanation.

Analysis of LeuRS (Hsu and Martinis, 2008) had already suggested the hypothesis that the C-terminal domain may function as a general RNA binding domain that enhances interactions with the tRNA substrate. Even, Guo et al. (2010) while examining the evolution of synthetases, have suggested that during the transition from the RNA to the protein world, aaRS might have had a chaperone function to protect the tRNA substrate from destruction by nucleases. These hypotheses might be consistent with our results showing that a short sequence might be responsible for this interaction and explain the suppressing effects we observe.

While the reduced size of suppressing peptides might open the way towards a treatment of mt diseases, several very important problems remain open. Further experiments are obviously necessary to define the extent of cross-suppressing activities (in particular as far as other aaRS and other mutated tRNAs are concerned) and the structural details of the suppressing molecules should be investigated.

At the same time to verify the possible effect of suppressive peptides on cultured cells from patients is obviously an essential step.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply indebted to M. Bolotin-Fukuhara, to S. Martinis and to C. Herbert for very helpful discussions and for the generous gift of several strains and plasmids. This work was supported by Telethon (GGP07164).

A.M. was a recipient of a Pasteur Institute-Cenci Bolognetti Foundation “Teresa Ariaudo” fellowship.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.mito.2011.08.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material.

References

- Bolender N., Sickmann A., Wagner R., Meisinger C., Pfanner N. Multiple pathways for sorting mitochondrial precursor proteins. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:42–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401126. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefoy N., Fox T.D. Directed alteration of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial DNA by biolistic transformation and homologous recombination. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;372:153–166. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-365-3_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca C., Besagni C., Frontali L., Bolotin-Fukuhara M., Francisci S. Mutations in yeast mt tRNAs: Specific and general suppression by nuclear encoded tRNA interactors. Gene. 2006;377:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca C., Zhou Y.F., Montanari A., Morea V., Oliva R., Besagni C., Bolotin-Fukuhara M., Frontali L., Francisci S. Can yeast be used to study mitochondrial diseases? Biolistic tRNA mutants for the analysis of mechanisms and suppressors. Mitochondrion. 2009;9:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuermann M., Francisci S., Rinaldi T., De Luca C., Rohou H., Frontali L., Bolotin-Fukuhara M. The yeast counterparts of human ‘MELAS’ mutations cause mitochondrial dysfunction that can be rescued by overexpression of the mitochondrial translation factor EF-Tu. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:53–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox T.D., Folley L.S., Mulero J.J. Analysis and manipulation of yeast mitochondrial genes. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:149–165. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M., Yang X.L., Schimmel P. New functions of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases beyond translation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:668–674. doi: 10.1038/nrm2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert C.J., Labouesse M., Dujardin G., Slonimski P.P. The NAM2 proteins from S. cerevisiae and S. douglasii are mitochondrial leucyl-tRNA synthetases, and are involved in mRNA splicing. EMBO J. 1988;7:473–483. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02835.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu J.L., Martinis S.A. A Flexible peptide tether controls accessibility of a unique C-terminal RNA-binding domain in leucyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;376:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu J.L., Rho S.B., Vannella K.M., Martinis S.A. Functional divergence of a unique C-terminal domain of leucyl-tRNA synthetase to accommodate its splicing and aminoacylation roles. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:23075–23082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Guan M. Human Mitochondrial Leucyl-tRNA synthetase corrects Mitochondrial dysfunctions due to the tRNALeu(UUR) A3243G Mutation, associated with Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Lactic Acidosis and Stroke-Like Symptoms and Diabetes. Mol. and Cellular Biol. 2010;30:2147–2154. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01614-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limongelli A., Schaefer J., Jackson S., Invernizzi F., Kirino Y., Suzuki T., Reichmann H., Zeviani M. Variable penetrance of a familial progressive necrotising encephalopathy due to a novel tRNA(Ile) homoplasmic mutation in the mitochondrial genome. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:342–349. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.016048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland R., Clark K., Morris A.A., Taylor R.W., Macphail S., Lightowlers R.N., Turnbull D.M. Multiple neonatal deaths due to a homoplasmic mitochondrial DNA mutation. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:145–146. doi: 10.1038/ng819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanari A., Besagni C., De Luca C., Morea V., Oliva R., Tramontano A., Bolotin-Fukuhara M., Frontali L., Francisci S. Yeast as a model of human mitochondrial tRNA base substitutions: investigation of the molecular basis of respiratory defects. RNA. 2008;14:275–283. doi: 10.1261/rna.740108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanari A., De Luca C., Frontali L., Francisci S. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are multivalent suppressors of defects due to human equivalent mutations in yeast mt tRNA genes. BBA-MCR. 2010;1803:1050–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulero J.J., Fox T.D. Alteration of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae COX2 mRNA 5'-untranslated leader by mitochondrial gene replacement and functional interaction with the translational activator protein PET111. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1993;4:1327–1335. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.12.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H., Davison E., King M. Overexpressed mitochondrial leucyl-tRNA synthetase suppresses the A3243G mutation in the mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) gene. RNA. 2008;14:2407–2416. doi: 10.1261/rna.1208808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paukstelis P.J., Lambowitz A.M. Identification and evolution of fungal mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases with group I intron splicing activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:6010–6015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801722105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohou H., Francisci S., Rinaldi T., Frontali L., Bolotin-Fukuhara M. Reintroduction of a characterized mit tRNA glycine mutation into yeast mitochondrial provides a new tool for the study of human neurodegenerative diseases. Yeast. 2000;18:219–227. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(200102)18:3<219::AID-YEA651>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorbach J., Yusoff A.A., Tuppen H., Abg-Kamaludin D.P., Chrzanowska-Lightowlers Z.M., Taylor R.W., Turnbull D.M., McFarland R., Lightowlers R.N. Overexpression of human mitochondrial valyl tRNAsynthetase can partially restore levels of cognate mt-tRNAVal carrying the pathogenic C25U mutation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3065–3074. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E.F., Maniatis T. ColdSpring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. [Google Scholar]

- Sasarman F., Antonicka H., Shoubridge E.A. The A3243G tRNALeu(UUR) MELAS mutation causes amino acid misincorporation and a combined respiratory chain assembly defect that is partially suppressed by overexpression of the translation elongation factors EFTu and EFG2. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:3697–3707. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinzl M., Vassilenko K.S. Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D139–D140. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukalo M., Yaremchuk A., Fukunaga R., Yokoyama S., Cusack S. The crystal structure of leucyl-tRNA synthetase complexed with tRNALeu in the post-transfer-editing conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:923–930. doi: 10.1038/nsmb986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann B., Neupert W. Mitochondria-targeted green fluorescent proteins: convenient tools for the study of organelle biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2000;16:1421–1427. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(200011)16:15<1421::AID-YEA624>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson F.H., Hariri A., Farhi A., Zhao H., Petersen K.F., Toka H.R., Nelson-Williams C., Raja K.M., Kashgarian M., Shulman G.I., Scheinman S.J., Lifton R.P. A cluster of metabolic defects caused by mutation in a mitochondrial tRNA. Science. 2004;306:1190–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1102521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.