Abstract

Perceived peer alcohol use is a predictor of consumption in college males; frequent references to alcohol on Facebook may encourage alcohol consumption. Content analysis of college males’ Facebook profiles identified references to alcohol. The average age of 225 identified profiles was 19.9 years. Alcohol references were present on 85.3% of the profiles; the prevalence of alcohol was similar across each undergraduate grade. The average number of alcohol references per profile was 8.5 but increased with undergraduate year (p = .003; confidence interval = 1.5, 7.5). Students who were of legal drinking age referenced alcohol 4.5 times more than underage students, and an increase in number of Facebook friends was associated with an increase in displayed alcohol references (p < .001; confidence interval = 0.009, 0.02). Facebook is widely used in the college population; widespread alcohol displays on Facebook may influence social norms and cause increases in male college students’ alcohol use.

Keywords: alcohol, college student, social networking, Facebook, Internet

Introduction

Alcohol use and abuse in college students has numerous consequences to health, safety, and academic success. Alcohol consumption increases the risk of participating in behaviors which result in morbidity and mortality in the college population, such as engaging in violence or driving over the speed limit and without a seatbelt (Field, Claassen, & O’Keefe, 2001; O’Brien et al., 2006). The vast majority of college students have tried alcohol, with 90% of the students reporting alcohol consumption at least one time during the past year (Kuo et al., 2002). Although most college students have tried alcohol, males consistently report higher rates of alcohol use and associated morbidity and mortality (Knight et al., 2002).

Male college students report significantly higher rates of both alcohol consumption and binge drinking (Goldman, 2002; Svenson, Jarvis, & Campbell, 1994; Wechsler, Dowdall, Davenport, & Castillo, 1995). Male students perceive less risk in consuming large quantities of alcohol and are likely to believe that health problems cannot result from drinking alcohol (Bewick et al., 2008; Spigner, Hawkins, & Loren, 1993; Svenson et al., 1994).

Among male students, there are important differences in drinking patterns between older and younger college students. Male students’ alcohol consumption tends to increase on reaching legal drinking age (Gross, 1993; Kuo et al., 2002; Svenson et al., 1994). Although legal aged male students may drink alcohol more frequently, underage students are more likely to report high-risk drinking behavior and drinking to the point of intoxication; 58% of underage males typically consume more than five drinks in one sitting compared with 41% of legal age males (Wechsler, Lee, Nelson, & Kuo, 2002; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008). College students consume beer or malt beverages the majority of the time and are likely to binge drink and become intoxicated more often when consuming these beverages (Chen & Paschall, 2003).

In addition to heavier drinking patterns seen in male students, fewer opportunities exist to identify and intervene with at-risk male drinkers. Male students are much less likely than female students to seek health care or attend annual check-up appointments (Boynton Health Services, 2009; Dawson, Schneider, Fletcher, & Bryden, 2007). Innovative approaches are needed to complement current efforts to identify problem drinking behaviors on college campuses, especially among students who may not be seen in clinics. One such approach may be via social networking sites (SNSs), such as Facebook. Facebook provides a unique view of college students’ lives and disclosures of alcohol consumption in an accessible online setting. Previous studies have shown that adolescents share a large amount of personal information, references to mental health, and risk behaviors such as alcohol use, sexual behaviors, substance use, and violence (Egan & Moreno, 2010; Hinduja & Patchin, 2008; Moreno, Parks, Zimmerman, Brito, & Christakis, 2009).

The average college student uses Facebook for 30 minutes each day and as many as 98% of college students maintain active Facebook profiles (Compete.com, 2009; Lewis, Kaufman, & Christakis, 2008; Pempek, Yermolayeva, & Calvert, 2009; Zuckerberg, 2010). Because of the ubiquitous use of Facebook and the display of risk behaviors, Facebook has the potential to influence peer behavior and the development of social norms in college students. The majority of male students believe that intoxication of their same-gender peers is socially acceptable, and perceived peer norms are a more significant predictor of alcohol use in males than females (Read, Wood, Davidoff, McLacken, & Campbell, 2002; Svenson et al., 1994).

Facebook is unique in its potential use as a risk-identification tool because it not only allows the viewer to see disclosures of alcohol use but also allows one to see the frequency of alcohol use that the user chooses to display and to observe changes in displays of alcohol references over a period of time without relying on personal recollection. Before the validity of the use of Facebook as a formal indicator of alcohol use can be explored, it is necessary to gain a background of current references to alcohol by college students. The purpose of this study was to perform a content analysis of male undergraduates’ Facebook profiles for references to alcohol use among male college students, including timing and content of alcohol references. It was hypothesized that prevalence of alcohol references and patterns observed on Facebook would be similar to self-reported survey data available on male college students’ alcohol use. In addition, we hypothesized that displays of beer or malt beverages would be more frequent than displays of any other type of alcohol.

Method

Setting

This observational content analysis of profiles on the SNS Facebook (www.Facebook.com) was conducted between June and November 2009. Public Facebook profiles within a large midwestern university’s Facebook network were evaluated. The default privacy setting of Facebook allows profile content to be accessible to anyone within the profile owner’s Facebook networks. This study was determined exempt by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board because it included observation of publicly available information.

Participants

Facebook profiles were identified through a search of profile owners who had chosen to have their profile viewable to their public network. The sample was further defined using the following Facebook search criteria: male students with school status of undergraduate and graduation class of 2010, 2011, or 2012: the rising senior, junior, and sophomore classes. The goal of the sample collection was to assess students who had completed at least one undergraduate year. Three searches were done to complete this phase of the study; one search was completed to identify profiles from each of the three selected graduation classes.

Profiles were included if they met the following criteria: male student with age self-reported as 18 to 23 years and profile showing signs of activity within the past 30 days. Profiles were excluded if one or more sections of the profile were set to private. Additionally, profiles were excluded if more than 10% of the profile was not in English or the profile owner was not in the correct University network. An example of a profile owner, which would appear in the Facebook search, but was not in the right network, may be a student who was planning on transferring from the University but had not yet done so or who no longer attended the University. Profiles of individuals who are Facebook “friends” of the individual viewing the search results are listed first in the results; in our study, these profiles were excluded to eliminate biases and maintain protocols of only coding public information. “Friending” on Facebook involves two individuals who have chosen to link profiles and share all profile information.

Data Collection

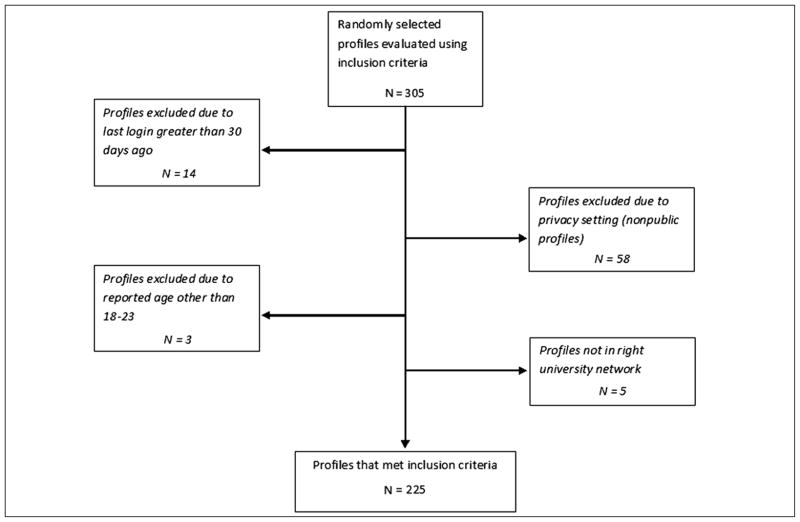

The Facebook search engine provides a sample of up to 500 profiles that meet selected criteria. Profiles that met inclusion criteria were selected for evaluation in the order that they appeared in the search until the sample size goal of 225 profiles was met. Figure 1 depicts our profile selection strategy.

Figure 1.

Inclusion criteria flowchart

Each profile was viewed once for references occurring prior to June 1, 2009, through the date when the profile was formed. Profiles were not archived, printed, or saved. No attempts were made to contact subjects regarding their profiles or to access information that was not publicly available. A goal sample size of 225 profiles was chosen based on previous Facebook data collection analysis (Egan & Moreno, 2010). Content analysis was performed on each profile that met inclusion criteria by reviewing all available profile data in sections designated by the research design (n = 225).

Facebook includes several features that are useful in identifying displayed alcohol references and related risk factors in college students. Facebook users may choose to share personal information with the public, such as hobbies, interests, and activities on their profile. Facebook allows users to share personal photographs and to identify themselves and friends in posted photos. A widely used feature of Facebook is called “status updates,” which allows users to share short text descriptions of their current location, emotion, or activity. An example of a status update might be “Alex is in biology class” or “Sam is happy today.” Facebook includes several optional applications that allow users to display downloaded icons and images. One popular application, called “Bumper Stickers,” allows users to post downloaded icons on their friends’ profiles. To be displayed, the icons must be accepted by the profile owner. Bumper stickers may contain a combination of photographs, text, logos, and graphics.

A code book developed during our previous work was used to review profile content (Moreno et al, 2009). The code book defined key terms that were considered references to alcohol use. Table 1 contains examples of code words used in identifying references on Facebook profiles and examples of references.

Table 1.

Criteria for Alcohol References

| Category | Example Code Words | Example Text References |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol beverages | Beer, wine, liquor, martini, cold one | “Enjoying an ice cold beer or six with the guys tonight.” |

| Missing class or activity due to drinking | Forgetting about something, problems with school, guilt (due to alcohol use) | “Partied it up to the fullest, but missed my first class due to a massive hangover.” |

| Intoxication | Drunk, hung over, blacking out, wasted | “German beer … and drunk by 10 am.” |

| Drinking activity or game | Partying, bars, beer pong, keg stand, flip cup, beer bong | “Keg stand champ last night … 40 seconds strong!” |

The date when alcohol references were displayed on Facebook was recorded. The date of display was coded as occurring either before the profile owner entered college (August 31 of high school graduation year) or as occurring while the profile owner was in college (September 1 of high school graduation year). For example, a profile owner with a college graduation year of 2012 would have references to alcohol occurring on or before August 31, 2008, coded as High School and references occurring on or after September 1, 2008, coded as College.

Variables

Demographic data were recorded from profiles, including age, relationship status, and sexual preference, which are self-reported in the personal information page of Facebook profiles. Facebook use variables included the number of days since last Facebook activity, number of Facebook friends of the profile owner, and date of profile formation. The number of days since last Facebook activity was measured by identifying the last date of status update or other wall post made by the profile owner.

Analysis of profiles for references to alcohol occurred through viewing of profile pictures, personal pictures, group names, status updates, personal information section, and bumper stickers. An example of a picture alcohol reference would be the profile owner holding a beer can or bottle of alcohol. An example of a text reference to alcohol would be a status update by the profile owner stating that they were drunk, hungover, or consuming alcohol. Only pictures that clearly contained a labeled alcoholic beverage and text references, which explicitly mentioned alcohol, consuming alcohol, or a state related to alcohol, were recorded. The alcohol references were further categorized into subcategories of references to beer or other types of alcohol (liquor, wine, mixed drinks) when applicable.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 9.0 (2003; Statacorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were calculated to determine prevalence of references to alcohol. Logistic regression was used to determine associations between alcohol and age, grade level, and Facebook usage variables. Timing of alcohol reference displays was graphed on a timeline based on prevalence of references per month.

Results

A total of 305 profiles were viewed to obtain a target sample size of 225 profiles; 72% of the profiles met inclusion criteria. The predominant reason for exclusion was having one or more sections of the profile set as private (19%). All the 225 profiles that were examined belonged to male undergraduate students by study design. The mean age reported on the profiles was 19.8 years (SD = 1.2). More than 68% of the profiles belonged to students who were under the legal U.S. drinking age of 21 years at the time their profile was coded. The profiles were selected from the graduating classes of 2010, 2011, and 2012, with a third of the sample size belonging to each class (75 profiles) as was planned by study design. Of the subjects who reported relationship status (n = 165), 62% were single and 35% were in a relationship. The majority of subjects (n = 203) reported sexual preference; 97.5% of these reported heterosexual interests.

Study Population Facebook Use

The mean number of days since last activity was 4.6 days (SD = 5.66). The number of Facebook friends was displayed on the majority of profiles (n = 199). There was a large range of the number of Facebook friends, with a minimum of 119 and a maximum of 1,607 friends. The average number of Facebook friends was 507 (SD = 249). There was an increase in the average number of friends by year, from 496 average friends for class of 2012, 509 friends for class of 2011, to 517 friends for class of 2012. The increase was not statistically significant. The majority of profiles were formed 2.6 years prior to evaluation (SD = 0.54), which was consistent with previous data (Egan & Moreno, 2010). Demographic data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic Data from Facebook Profiles (N = 225)

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 225 | 100 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18 | 16 | 7.1 |

| 19 | 75 | 33.5 |

| 20 | 62 | 27.7 |

| 21 | 68 | 30.4 |

| 22 | 3 | 0.9 |

| 23 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Underage (<21 years) | 154 | 68.6 |

| Legal age (≥21 years) | 71 | 31.4 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 102 | 45.3 |

| In a relationship | 63 | 28.0 |

| Not reported | 60 | 26.6 |

| Sexual preference | ||

| Female | 198 | 88.0 |

| Male | 5 | 2.2 |

| Not reported | 22 | 9.8 |

Alcohol

References to alcohol were present on 85.33% of the profiles; this was consistent across the three classes. The average number of alcohol references per profile was 8.5 (SD = 10.6). The range of references to alcohol was 0 to 72 displays. Although the prevalence of alcohol was consistent across each year in college, the number of references displayed increased by year in college, with students who were closer to graduating displaying significantly more references than underclassmen. Students who were of legal drinking age (21 years or older) had an average of 4.5 more references per profile than underage students (p = .003; confidence interval [CI] = 1.5, 7.5).

Of the subjects who displayed alcohol, few (0.65%) displayed references to alcohol only during high school. The majority of the subjects (77.2%) displayed references to alcohol only during college. The remaining profiles (22.1%) displayed references to alcohol both during high school and college. Similar to the absolute prevalence of alcohol, the timing of references was similar throughout each class.

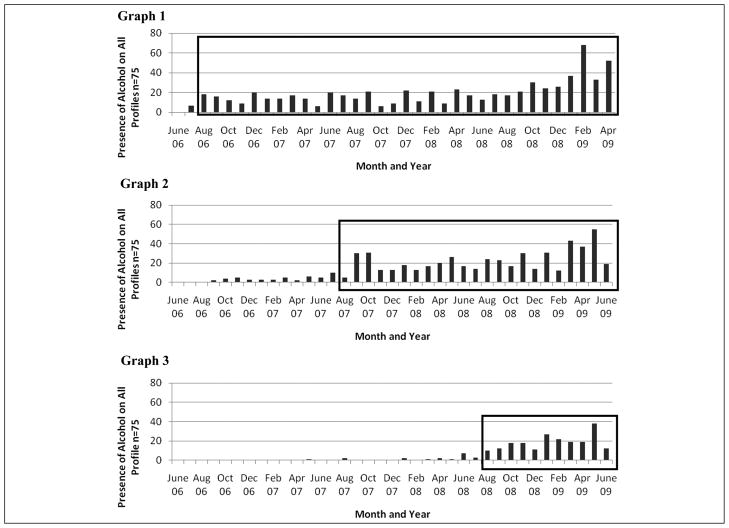

The timing of references, by month of occurrence on Facebook, is shown in Figure 2 for references by class. There was an increase in displays of alcohol references on entering college for class of 2011 and class of 2012, both of which contained data from high school and college. Limited data from high school existed for the class of 2010. Additionally, the display of references to alcohol continued to increase throughout college for each class.

Figure 2.

Graphs depict the total number of alcohol references made by the cohort of profiles in each grade for each month during three year period of June 2006 through June 2009. Bold boxes indicate the references made by the cohort during college. Graph 1: Alcohol references by class of 2010: Freshman through Junior year of college. Graph 2: Alcohol references by class of 2011: Senior year of high school through Sophomore year of college. Graph 3: Alcohol references by class of 2012: Junior year of high school through Freshman year of college.

In addition to quantity and timing of alcohol references, references were coded as containing either beer/malt beverages or liquor. Profiles were more likely to contain references to beer/malt beverages than any other type of alcohol (odds ratio = 3.7; CI = 0.85, 6.55). The average number of references to beer was 3.9 per profile and to other types of alcohol 1.0. The number of references to both beer and other types of alcohol increased with increasing class year.

An increase in the number of friends was associated with a statistically significant increase in the number of displayed alcohol references per profile (p < .001; CI = 0.009, 0.02). The number of alcohol references was not associated with relationship status or sexual preference. Using logistic regression, a model was created for Facebook usage, which incorporated number of friends, date of last activity, and date of profile origin. There was no statistical significance for the number of alcohol references using this model. A summary of all alcohol statistics is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Alcohol Statistics

| Profiles With Alcohol Present | Mean (SD) Alcohol References Per Profile | Range— Alcohol References | Alcohol References—Only High School | Alcohol References— Both High School and College | Alcohol References— Only College | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 85.3% | 8.5 (10.6) | 0–72 | 0.7% | 22.1% | 77.2% |

| Graduating class of 2010 | 85.3% | 10.4 (12.1) | 0–72 | 0.0% | 23.7% | 76.3% |

| Graduating class of 2011 | 88.0% | 8.9 (10.9) | 0–55 | 0.0% | 25.0% | 75.0% |

| Graduating class of 2012 | 82.7% | 6.3 (8.2) | 0–43 | 2.0% | 17.6% | 80.4% |

Conclusion

A previous study by our research team using Facebook to identify displayed alcohol references in college students showed that 73% of students displayed references to alcohol on their Facebook profiles (Egan & Moreno, 2010). This study identified the rate of male college students who display references to alcohol to be higher than this average. This is consistent with the higher prevalence of alcohol consumption seen in male students (Knight et al., 2002).

Although the overall prevalence of alcohol was consistent throughout college in this study, the number of references increased with age. Multiple explanations should be considered for this observed trend. Trends could reflect patterns that are seen in male alcohol use on college campuses, with alcohol consumption increasing throughout college (Kuo et al., 2002). Alternatively, references could accumulate on profiles over time; however, the majority of subjects had 3 years of data existing on profiles. Students may also be prompted to display alcohol after turning the legal age of 21 years because of fewer perceived consequences from references.

Adolescents who view references to alcohol on SNSs have been reported to interpret these displays as either actual behavior or attempts by their peers to appear socially acceptable (Moreno, Briner, Williams, Walker, & Christakis, 2009). This idea is supported by previous research that shows that the strongest influence on alcohol consumption rates among college students is perceived peer use (Perkins, 2002; Perkins, Haines, & Rice, 2005). Given the high prevalence of alcohol use displayed on Facebook and the popularity of SNSs among college students, these displays might serve to influence behavior. The “Super Peer” theory suggests that media may exceed traditional peer influences for forming of peer social norms (Strasburger & Wilson, 2002). Furthermore, college students typically overestimate the rates of alcohol consumption and problem drinking behavior by their peers, and exposure to this new medium may increase misconceptions about alcohol use (Perkins, 2002).

It is interesting to note that there was a large increase in the number of references seen on Facebook profiles when entering college, as well as the fact that male college students who displayed a higher number of references to alcohol also had more Facebook friends. College freshmen often attend alcohol-related events to socialize, and note making friendships and being popular as a main motivator for consuming alcohol (Borsari, Murphy, & Barnett, 2007). Acceptance among freshmen peers is often linked to high levels of alcohol consumption (Maggs, 1997). The role that Facebook alcohol references play in forming relationships is unknown. Displaying alcohol references could be a mechanism used in friendship development and peer acceptance by male students.

Ethical considerations of the use of Facebook or other SNSs to investigate behavior in college students warrant discussion (Moreno, Fost, & Christakis, 2008; Pujazon-Zazik & Park, 2010). This study was observational in nature and can be compared with observing human behavior in a public setting. As with any observational study, subjects may not always be aware that they are research subjects (Boyd, 2008). In contrast to observational study subjects who may not necessarily have chosen to make their conversations or interactions public, Facebook users included in our study have made a conscious decision to make content available to the public. SNSs are emerging as a useful tool for health research as well as in other areas such as screening potential job or college applicants (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008; Farmer, Holt, Cook, & Hearing, 2009; Hinduja & Patchin, 2008; Kluemper & Rosen, 2009).

Limitations

Limitations based on our sample population should be addressed. First, our sample was limited to one university and generalization to other populations is unknown. Further investigation should focus on other college populations. It is known that alcohol consumption rates in college campuses differ by state in the United States, so it is likely that future searches may yield valuable differences (Nelson, Naimi, Brewer, & Wechsler, 2005).

Our study used only one SNS; however, an estimated 97% of undergraduate students use Facebook, so it is likely that these results are representative of students at this university (Lewis et al., 2008). Future studies should investigate alcohol displays on other SNSs. Although we attempted to obtain a random sample in this study, it is unknown how search results appear in Facebook searches; at the time of this study, results were displayed in a non-alphabetical, nonnumerical order. This study involved the observation of public profiles; although only 19% of profiles were excluded due to privacy, the alcohol reference characteristics of students who have private profiles are unknown.

Implications

Because of the widespread use of Facebook among college students, Facebook has the potential to have an impact on perception of peer alcohol use, behavior related to alcohol use, and intent to display references by peers. Male college students, in particular incoming freshmen, may view Facebook alcohol references and consider these in developing perceived peer norms.

In the future, Facebook may present a novel way of assessing intervention needs on a college campus (Pujazon-Zazik & Park, 2010). In addition to current intervention and screening resources currently used on campus, Facebook could be used to screen individuals for alcohol abuse conditions. Further research should examine using Facebook references as a way to predict high-risk alcohol behavior. Facebook may also be a useful tool to disseminate information about alcohol awareness programs, substance abuse counseling, or alternative social activities to college students. The ability to approach college students in their natural online environment may present a nonthreatening way to provide resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express appreciation to Michael Swanson, Lauren Jelenchick, and Libby Brockman for assistance in manuscript editing and preparation.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article:

The project described was supported by Award Number K12HD055894 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and by a Medical Scholars Summer Research Fellowship from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, the National Institutes of Health, or the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

References

- Bewick BM, Mulhern B, Barkham M, Trusler K, Hill AJ, Stiles WB. Changes in undergraduate student alcohol consumption as they progress through university. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Murphy JG, Barnett NP. Predictors of alcohol use during the first year of college: Implications for prevention. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2062–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd D. How can qualitative internet researchers define the boundaries of their projects: A response to Christine Hine. In: Markham A, Baym N, editors. Internet inquiry: Conversations about method. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2008. pp. 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton Health Services, University of Michigan. Health and academic performance, Minnesota postsecondary students. Minneapolis: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Buffardi LE, Campbell WK. Narcissism and social networking web sites. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:1303–1314. doi: 10.1177/0146167208320061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Paschall M. Malt liquor use, heavy/problem drinking and other problem behaviors in a sample of community college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:835–842. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compete.com. Site profile for Facebook.com. 2009 July 15; Retrieved from http://siteanalytics.compete.com/facebook.com.

- Dawson KA, Schneider MA, Fletcher PC, Bryden PJ. Examining gender differences in the health behaviors of Canadian university students. Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 2007;127:38–44. doi: 10.1177/1466424007073205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan K, Moreno MA. Prevalence of stress references on college freshmen. Facebook profiles. 2010 doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3182160663. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AD, Holt C, Cook MJ, Hearing SD. Social networking sites: A novel portal for communication. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2009;85:455–459. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.074674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CA, Claassen CA, O’Keefe G. Association of alcohol use and other high-risk behaviors among trauma patients. Journal of Trauma. 2001;50:13–19. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS. College drinking, what it is, and what to do about it: A review of the state of the science—National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Task Force on College Drinking—Introduction. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement. 2002;(14):5. [Google Scholar]

- Gross WC. Gender and age differences in college students’ alcohol consumption. Psychological Reports. 1993;72:211–216. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Personal information of adolescents on the Internet: A quantitative content analysis of MySpace. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31:125–146. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluemper DH, Rosen PA. Future employment selection methods: Evaluating social networking web sites. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2009;24:567–580. [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo MC, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:263–270. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M, Adlaf EM, Lee H, Gliksman L, Demers A, Wechsler H. More Canadian students drink but American students drink more: Comparing college alcohol use in two countries. Addiction. 2002;97:1583–1592. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K, Kaufman J, Christakis N. The taste for privacy: An analysis of college student privacy settings in an online social network. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2008;14:79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL. Alcohol use and binge drinking as goal-directed action during the transition to post-secondary education. In: Schulendberg J, Maggs JL, Hurrelmann K, editors. Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 345–371. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, Briner LR, Williams A, Walker L, Christakis DA. Real use or “real cool”: Adolescents speak out about displayed alcohol references on social networking websites. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:420–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, Fost NC, Christakis DA. Research ethics in the MySpace era. Pediatrics. 2008;121:157–161. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, Parks MR, Zimmerman FJ, Brito TE, Christakis DA. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and associations. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:27–34. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Wechsler H. The state sets the rate: The relationship among state-specific college binge drinking, state binge drinking rates, and selected state alcohol control policies. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:441–446. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MC, McCoy TP, Champion H, Mitra A, Robbins A, Teuschlser H, DuRant RH. Single question about drunkenness to detect college students at risk for injury. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006;13:629–636. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pempek TA, Yermolayeva YA, Calvert SL. College students’ social networking experiences on Facebook. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30:227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement. 2002;(14):164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Haines MP, Rice R. Misperceiving the college drinking norm and related problems: A nationwide study of exposure to prevention information, perceived norms and student alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:470–478. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujazon-Zazik M, Park MJ. To tweet, or not to tweet: Gender differences and potential positive and negative health outcomes of adolescents’ social Internet use. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2010;4:77–85. doi: 10.1177/1557988309360819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Davidoff OJ, McLacken J, Campbell JF. Making the transition from high school to college: The role of alcohol-related social influence factors in students’ drinking. Substance Abuse. 2002;23:53–65. doi: 10.1080/08897070209511474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spigner C, Hawkins W, Loren W. Gender differences in perception of risk associated with alcohol and drug use among college students. Women & Health. 1993;20:87–97. doi: 10.1300/J013v20n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasburger VC, Wilson BJ. Children, adolescents, and the media. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Svenson LW, Jarvis GK, Campbell RL. Gender and age differences in the drinking behaviors of university students. Psychological Reports. 1994;75(1 Pt 2):395–402. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1994.75.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Davenport A, Castillo S. Correlates of college student binge drinking. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:921–926. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Nelson TF, Kuo M. Underage college students’ drinking behavior, access to alcohol, and the influence of deterrence policies. Findings from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:223–236. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:481–490. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerberg M. Six years of making connections. 2010 February 4; Retrieved from http://blog.facebook.com/blog.php?post=287542162130.