Abstract

The sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter-2 (SVCT2) is the only ascorbic acid (ASC) transporter significantly expressed in brain. It is required for life and critical during brain development to supply adequate levels of ASC. To assess SVCT2 function in the developing brain, we studied time-dependent SVCT2 mRNA and protein expression in mouse brain, using liver as a comparison tissue because it is the site of ASC synthesis. We found that SVCT2 expression followed an inverse relationship with ASC levels in the developing brain. In cortex and cerebellum, ASC levels were high throughout late embryonic stages and early post-natal stages and decreased with age, whereas SVCT2 mRNA and protein levels were low in embryos and increased with age. A different response was observed for liver, in which ASC levels and SVCT2 expression were both low throughout embryogenesis and increased post-natally. To determine whether low intracellular ASC might be capable of driving SVCT2 expression, we depleted ASC by diet in adult mice unable to synthesize ASC. We observed that SVCT2 mRNA and protein were not affected by ASC depletion in brain cortex, but SVCT2 protein expression was increased by ASC depletion in the cerebellum and liver. The results suggest that expression of the SVCT2 is differentially regulated during embryonic development and in adulthood.

Keywords: Ascorbic acid, sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter, brain, liver, development

1. INTRODUCTION

Ascorbic acid (ASC) is critical for brain function and formation, especially during development. It is transported into cells against a gradient via two isoforms of the sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter (SVCT1 and SVCT2) [1]. SVCT1 is expressed mainly in epithelial tissues and is responsible for intestinal absorption and kidney reabsorption of ASC. SVCT2 is expressed in most tissues, with the highest expression levels in adrenal glands and brain. Both the SVCT1 and SVCT2 are expressed in liver. However, the SVCT2 is the only ASC transporter substantially expressed in brain, where it concentrates ASC via a two-step SVCT2-dependent mechanism. ASC is first transported from blood (30–60μM) across the epithelial cells of the choroid plexus into cerebrospinal fluid where concentrations reach 200–400μM and is then taken up into neurons where concentrations reach 3–10mM [2,3]. Brain ASC content is highest at birth and decreases during post-natal development [4]. The need for ASC throughout development is most likely for its antioxidant role to combat the increased oxidative stress that occurs during these early stages of development resulting from organogenesis and neuronal maturation. ASC also mediates several other functions in brain, including acting as a cofactor in dopamine and collagen synthesis [2]. Significantly, mice that lack the SVCT2 die at birth, despite the ability to synthesize their own ASC by embryonic day 15 [5]. These mice exhibit very low ASC levels and severe hemorrhage and cell death in the brain, demonstrating a requirement of this transporter for survival [6,7,8]. These findings highlight the critical importance of ASC in the brain during development.

In mammals that can make their own ASC, synthesis can be up-regulated when ASC requirements are increased, such as during pregnancy, when there is a drain on maternal supply by the fetus [9,10]. Humans and primates have lost the ability to synthesize ASC due to a loss-of-function mutation in the gulonolactone oxidase (Gulo) gene and thus must ensure optimal levels through dietary intake. However, many studies have shown different populations such as pregnant women, smokers, and people with diabetes have lower levels of circulating ASC [11,12,13]. Protective mechanisms exist to preserve ASC in critical organs, including preferential retention in brain and ASC recycling [14], but the regulation of these is not yet understood.

The present experiments were performed to better understand SVCT2 regulation. Previous studies have shown that SVCT2 expression is determined by the ASC level in C2C12 myotubes [15], osteoblasts [16], astrocytes [17], and brain endothelial cells [18]. However, the regulation of SVCT2 by a range of ASC levels has not been studied in vivo. In Experiment 1, we determined the expression pattern of SVCT2 through a critical period of brain development from embryonic day 15 to post-natal day 32. In Experiment 2, using gulo(−/−) mice that are unable to synthesize ASC [19], we determined whether changes in tissue ASC level can regulate SVCT2 mRNA and protein in vivo.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Animals

Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J mice were originally obtained from Jackson laboratories (stock #000664; Jackson laboratories, USA) and maintained as a colony by in-house breeding. Gulo(−/−) mice were acquired by breeding heterozygous gulo(+/−) mice, obtained from Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Centers (http://www.mmrrc.org, #000015-UCD) and maintained on a C57BL/6J background. Mice were housed in breeding pairs (Experiment 1) or in single sex groups of 3–5 mice (Experiment 2) in tub cages in a temperature-and humidity-controlled vivarium. Mice were kept on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle, with lights on at 6 AM. They had free access to food and water for the duration of the experiment. All procedures were approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.1.1 Experiment 1

WT pregnancies were determined by the presence of a vaginal plug. Pregnant dams were sacrificed by anesthetization from inhaled isofluorane and decapitation at embryonic day 15 and 18. Fetuses were delivered by cesarean section and placed on a petri dish on ice to induce hypothermia. Fetuses were then quickly decapitated. Post-natal pups were sacrificed by decapitation at post-natal day 1 (P1, day of birth), P10, P18, and P32 after inhalation of isofluorane. Cortex, cerebellum, and liver were removed from each animal and tissues were quickly frozen and stored at −80 °C until needed.

2.1.2 Experiment 2

Four-week old gulo(−/−) mice were supplemented with varying levels of ASC in the drinking water. Prior to the experiment, all gulo(−/−) mice were maintained on deionized water containing 0.33 g/L ASC (standard, STD) (Sigma, USA) with 20μl/L EDTA to increase stability of ASC in solution. This is the standard supplement level that provides adult gulo(−/−) mice with approximately WT levels of ASC in tissues [19,20]. At four weeks of age, gulo(−/−) mice were placed on their respective ASC supplements (HIGH 3.33g/L, STD 0.33g/L, LOW 0.033g/L, or WATER (WTR) 0.00g/L) for 4 weeks. Four weeks is enough time for tissue ASC levels to adjust to a steady-state level [10]. More than 4 weeks without ASC supplementation can cause scurvy in gulo(−/−) mice. Signs of scurvy were monitored in these mice, including weight loss, loss of hair, and changes in gait and posture. Removal of ASC supplementation can lead to weight loss in gulo(−/−) mice, so the WTR group remained on STD supplementation until 5 weeks of age to allow for additional weight gain before removal of supplements.

2.2 ASC Determination

To measure intracellular ASC, tissues were homogenized in a lysis buffer containing 0.1 ml of 25% (w/v) metaphosphoric acid and 0.35 ml of 0.1 M Na2HPO4 and 0.05 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. The tissue homogenate was centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min at 13,000×g, and the supernatant was taken for assay of ASC. Assay of ASC was performed in duplicate by high performance liquid chromatography as previously described [10,21]. Data were expressed per gram wet tissue weight.

2.3 Malondialdehyde (MDA) determination

MDA, a product of lipid peroxidation, was measured to detect any differences in oxidative stress among the genotypes. MDA was measured as thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) as previously described [10]. Briefly, tissue samples were homogenized in 5% trichloroacetic acid, centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min at 13,000×g, and supernatants collected. Equal volume of 0.5M thiobarbituric acid was added to the supernatant. Samples were incubated in a 95°C water bath for 35 minutes. Fluorescence was read on a spectrophotometric plate reader with an excitation wavelength of 515 nm and emission wavelength of 553 nm. Data were determined per gram tissue (wet weight).

2.4 Extraction of total RNA and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted by using GenElute™ Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Tissue samples were homogenized with an electric homogenizer, and total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentrations were determined and confirmed as free from protein contamination by measuring absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. Equal amounts of RNA were used to synthesize cDNA using TaqMan® Reverse Transcriptase (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was stored at 80 °C until used.

2.5 Quantitative RT-PCR

RT-PCR reactions were performed in duplicate by using the iQ SYB® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The forward and reverse primers for SVCT2 were AAGGATGGACGGCATACAAG and TCTGTGCGTGCATAGTAGCC, respectively, and for β-actin, GTTTGAGACCTTCAACACCCC and GTGGCCATCTCCTGCTCGAAGTC. Reactions were performed on an iCycler iQ Multicolor real-time PCR machine (Bio-Rad). SVCT2 mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to E15.5 (Experiment 1) or to WT (Experiment 2).

2.6 Western Blotting

SVCT2 immunoblotting was performed as previously described [18]. Solubilized protein (15μg) was subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (7.5% gel) according to the method of Laemmli [22]. The SVCT2 was probed with an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:200) that was specific for the SVCT2 transporter (sc-30114, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). β-actin (1:400) served as a control for the amount of sample loaded (sc-1616, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Following appropriate secondary incubations, bands were illuminated using ECL Plus Western blotting reagents (RPN 2132, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Densitometry was determined using ImageJ and SVCT2 was normalized to expression of beta;;-actin and expressed relative to E15.5 (Experiment 1) or WT (Experiment 2).

2.7 Statistics

Data were analyzed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows. A univariate ANOVA was conducted for each dependent variable with age or ASC supplementation as the between-groups variable. After significant omnibus ANOVA, follow-up comparisons were conducted using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc test. Data are expressed as ±SEM.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Experiment 1

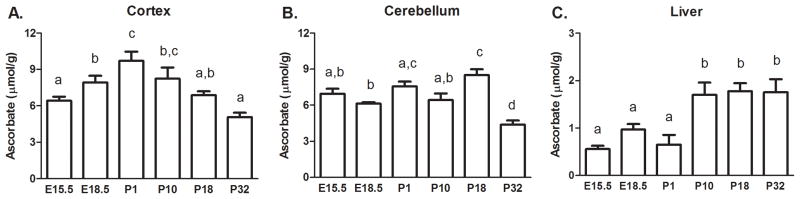

3.1.1 Ascorbate content in brain during development

Cortex ASC levels varied significantly depending on age (p<0.001, Fig. 1A). ASC content was highest at post-natal day 1 (P1) and then decreased significantly, reaching average adult cortex ASC levels by P32. ASC also increased between embryonic day 15.5 (E15.5) and P1. The cerebellum had similarly high levels of ASC throughout development and ASC content was significantly decreased by P32 (p<0.001, Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the liver exhibited an opposite pattern of ASC content, which was to increase with age (p<0.001, Fig. 1C). ASC levels were significantly lower in liver during embryogenesis and increased to a steady level during post-natal development (P1-P32).

Figure 1.

ASC content in brain and liver during development. (A) Cortex (B) Cerebellum (C) Liver, n=4–6 samples per group for all tissues. Groups that do not share the same letter are different, p<0.05.

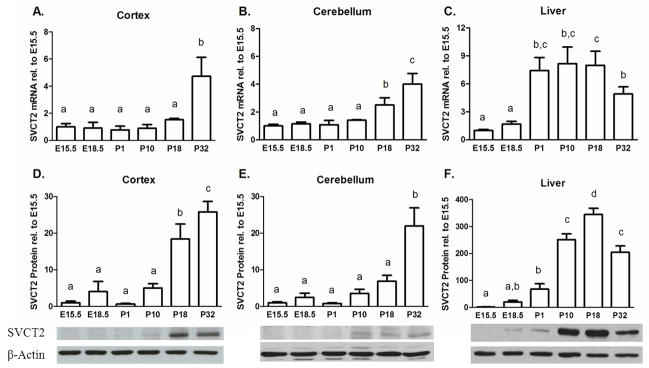

3.1.2 SVCT2 expression during Development

Brain SVCT2 mRNA levels were low and varied inversely with brain ASC content throughout embryogenesis and post-natal development. In the cortex, SVCT2 mRNA increased 5-fold by P32 (p<0.01, Fig. 2A). A similar pattern in SVCT2 mRNA expression was seen in the cerebellum except that increased expression began earlier with a 3-fold change by P18, and a further increase at P32 (p<0.001, Fig. 2B). The same developmental pattern of SVCT2 expression occurred in liver, where SVCT2 mRNA was low during embryogenesis and then dramatically increased post-natally (p<0.001, Fig. 2C). However, this pattern in liver mirrored ASC content instead of being inversely proportional, as occurred in brain. SVCT2 protein levels measured by Western blots changed similarly to mRNA levels in the cortex, cerebellum, and liver (Fig. 2D-F). SVCT2 protein increased with age by about 30-fold in cortex (p<0.001, Fig. 2D) and cerebellum (p<0.001, Fig. 2E) and almost 400-fold in liver (p<0.001, Fig. 2F). Representative blots are shown for each tissue type.

Figure 2.

SVCT2 mRNA (A–C) and protein (D–F) levels throughout development. (A) Cortex mRNA, n=3 samples per group (B) Cerebellum, n=3 samples per group (C) Liver, n=4–6 samples per group (D) Cortex protein, n=6 samples per group (E) Cerebellum, n=6 samples per group, (F) Liver, n=6 samples per group. Immunoblots are representative of quantification. Groups that do not share the same letter are different, p<0.05.

3.2 Experiment 2

In Experiment 1, SVCT2 expression followed an inverse relationship with ASC content in the brain but not liver. In order to further explore the regulation of SVCT2 in vivo by its own substrate, separate from any specific developmental processes, adult gulo(−/−) mice were maintained on different levels of ASC supplementation for 4 weeks prior to tissue acquisition.

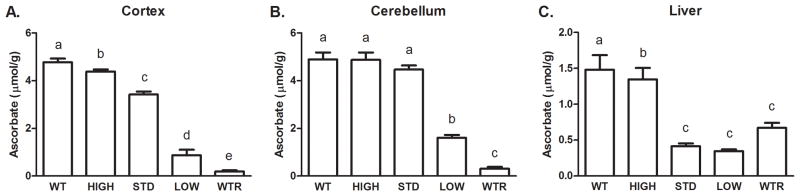

3.2.1 ASC content in different ASC supplementation groups

As expected, tissue ASC content was directly related to the level of ASC supplementation in the drinking water. In cortex and cerebellum, ASC levels in each supplementation group were significantly different from each other (p<0.001, Fig. 3A). In cerebellum, ASC levels were similar in the WT, HIGH, and STD groups, with a 5-fold decrease in the LOW group and negligible levels in the WTR group (p<0.001, Fig. 3B). In the liver, the STD, LOW, and WTR groups each had significantly lower ASC than the WT and HIGH groups (p<0.001, Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

ASC content in mice unable to synthesize their own ASC on different supplements for four weeks. (A) Cortex, n=5–7 samples per group (B) Cerebellum, n=5–7 samples per group (C) Liver, n=4–7 samples per group. Groups that do not share the same letter are different, p<0.05.

3.2.2 Oxidative stress in the tissues of gulo(−/−) mice with varying ASC

There was a small increase in oxidative stress (OxS) in the cortex in the LOW and WTR groups as measured by MDA (data not shown), although only the WTR group had significantly greater MDA than the WT, HIGH, and STD groups (p<0.05). There was no difference in lipid peroxidation among supplementation groups in the cerebellum (p=0.37) or liver (p=0.29).

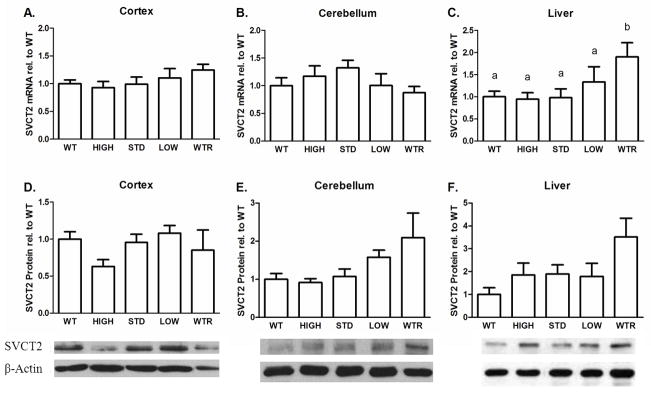

3.2.3 SVCT2 expression

There were no significant differences among the groups in either of the brain areas in SVCT2 mRNA levels (p’s>0.34 Fig. 4A, B). In the liver, SVCT2 mRNA expression was greater in the lower ASC groups (p<0.05, Fig. 4C) with the greatest increase in the WTR group compared to WT.

Figure 4.

SVCT2 mRNA (A–C) and protein (D–F) levels in mice on different ASC supplementations. (A,D) Cortex (B,E) Cerebellum (C,F) Liver, n=5–7 samples per group for all tissues. Immunoblots are representative of quantification. Groups that do not share the same letter are different, p<0.05.

There were no significant differences in SVCT2 protein in cortex (p=0.243, Fig. 4D). Although, there was a strong trend toward elevated SVCT2 protein levels in the cerebellum of the WTR group compared to the WT, HIGH, and STD groups (p=0.06, Fig. 4E), the omnibus ANOVA was not significant. Similarly, although the liver exhibited a 3-fold increase in the amount of SVCT2 protein in the WTR group compared to WT, the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.056, Fig. 4F). Representative blots are also shown.

4. DISCUSSION

The SVCT2 is thought to determine ASC content in brain and therefore the finding of an inverse relationship between ASC content in the cortex and cerebellum and the pattern of SVCT2 expression in developing mice was unexpected. ASC levels were high throughout embryogenesis and decreased post-natally similar to previous reports [4,23]. However, the relative SVCT2 mRNA and protein expressions were lower than expected in brain at early stages in development, raising the question of how ASC becomes concentrated in embryonic brain tissues. ASC accumulation is unlikely to be via SVCT1, which is not substantially expressed in brain [1]. It is also unlikely that an unknown ASC transporter is present or that uptake of ASC occurs as its oxidized form dehydroascorbate on glucose transporters, since mice that lack SVCT2 have negligible levels of ASC in the brain [7,10]. ASC levels may reflect changing cellular distribution in the brain with relatively higher ASC during periods of neurogenesis in the embryo compared to early post-natal life when gliogenesis occurs at a greater rate [4], since glial cells have been shown to lack the SVCT2 in vivo [24] and thus have lower ASC levels than SVCT2-expressing neurons [25]. Although this distinction does not help determine the mechanism behind disproportionate ASC accumulation, it is apparent that even the relatively low levels of SVCT2 are adequate to maintain the high ASC levels in cortex and cerebellum during embryogenesis.

The increase in post-natal SVCT2 expression mirrors that seen with the brain glucose transporters 1 & 3, which are low throughout embryogenesis and increase during post-natal development, reaching adult levels by post-natal day 30, in conjunction with neuronal maturation [26,27], suggesting a developmental regulation of the SVCT2. The increase in SVCT2 mRNA and protein during post-natal development could thus be due to the increase in neurogenesis; however, the increase in SVCT2 is exponential after post-natal day 18, after the majority of neurogenesis has occurred. There is also substantial growth of the brain vasculature after birth, but increased expression of the SVCT2 in endothelial cells cannot explain its increased post-natal expression, since endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier do not express the SVCT2 in vivo [28]. Lastly, it is also possible that increased OxS present after birth may decrease ASC content with age and also up-regulate the SVCT2. This possibility formed the basis for Experiment 2, in which we tested directly the possibility that ASC depletion and OxS levels in brain regulate SVCT2 expression in adult gulo(−/−) mice with varying dietary intakes of ASC.

As expected, dietary ASC depletion in the low supplementation (LOW) and unsupplemented (WTR) groups decreased ASC content in both brain regions and liver. These two dietary groups also showed only very minimal increases in lipid peroxidation in cortex, but not in cerebellum or liver. This suggests that ASC depletion to this degree does not cause substantial OxS in brain, at least following the short period of deprivation used here. Previously we showed that even the SVCT2 knockout mouse with very low brain ASC had only modest and localized increases in OxS markers of lipid peroxidation [8].

Our finding that dietary ASC depletion in gulo(−/−) mice did not affect SVCT2 mRNA expression in brain cortex or cerebellum agrees with the results of a recent study of SVCT2 regulation in whole brain by dietary ASC depletion in another mouse model that is similarly unable to synthesize ASC (SMP30/GNL) [29]. This group found that removal of ASC from the diet did not affect SVCT2 mRNA levels in total brain, although SVCT2 protein expression was not measured. In the present study, however, SVCT2 protein (but not mRNA) expression was up-regulated in the most extreme two ASC-depleted groups in cerebellum. These data suggest that the SVCT2 is differentially regulated in the two tissues, although the mechanisms underlying this difference are still not clear.

In contrast to brain, ASC content and SVCT2 expression increased with age in developing liver in normal mice. The increase in liver ASC may thus be explained in part by increased SVCT2 expression, but probably more so by the fact that wild-type fetuses can synthesize their own ASC by embryonic day 15 [5]. In the adult gulo(−/−) mouse, ASC depletion increased both SVCT2 mRNA and protein levels in liver, similar to results observed Amano and colleagues for SVCT2 mRNA [29]. In the liver there are additional considerations that do not apply to brain. The liver also expresses the SVCT1 and the exact contribution of each transporter has not yet been delineated. SVCT1 mRNA was also measured in our study (data not shown) and by the Amano group, with no differences found. SVCT2 is thought to transfer ASC from the blood stream into cells. Accordingly, the increase in SVCT2 in response to decreasing liver ASC levels in adult gulo(−/−) mice seems logical. In contrast, if the same relationship observed in the adult gulo(−/−) mice held true for developing pups it would predict that SVCT2 would be higher during the embryonic stages of development when all ASC for the liver must be obtained from maternal supply across the placenta. Once pups begin to synthesize their own ASC at the later embryonic stages, the contribution of the SVCT2 might become less significant in the liver. The fact that this is not the case, as reported here, is further indication that additional or alternative mechanisms are in place to supply fetal tissues with ASC, presumably reflecting the importance of maintaining high ASC levels during development.

The results of this study highlight three key elements. First, that ASC levels are high throughout embryogenesis in the brain and decrease with age, while in the liver they are lower in utero and increase post-natally. The high level of ASC in the brain during development reinforces the critical importance of the vitamin at this time. Second, that SVCT2 mRNA and protein in the cortex and cerebellum are low throughout the late gestational developmental stage and increase with age. Third, that in the adult gulo(−/−) mice, varying tissue ASC content did not alter SVCT2 mRNA or protein levels in the cortex but SVCT2 protein was increased by low tissue ASC levels in the cerebellum and liver. Liver SVCT2 mRNA was also increased with low ASC. These data suggest an alternate regulation mechanism of SVCT2 mRNA and/or protein expression in different tissues to allow for enhanced ASC transport and prevention of OxS.

Highlights.

SVCT2 expression levels in brain are low during development and increase with age.

In liver, SVCT2 levels are low during embryogenesis and increases post-natally.

In adult mice, ASC does not regulate SVCT2 mRNA in cortex or cerebellum.

Low ASC increases SVCT2 protein in the cerebellum of adult mice.

Low ASC up-regulates SVCT2 mRNA and protein in liver in adult mice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health (NS057674 to James M. May). The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SVCT2

sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2

- ASC

ascorbic acid

- Gulo

gulonolactone oxidase

- OxS

oxidative stress

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

M. Elizabeth Meredith, Email: Elizabeth.meredith@Vanderbilt.edu.

Fiona E. Harrison, Email: Fiona.harrison@Vanderbilt.edu.

James M. May, Email: James.may@Vanderbilt.edu.

REFERNCES

- 1.Tsukaguchi H, Tokui T, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, Chen XZ, Wang Y, Brubaker RF, Hediger MA. A family of mammalian Na+-dependent L-ascorbic acid transporters. Nature. 1999;399:70–75. doi: 10.1038/19986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison FE, May JM. Vitamin C function in the brain: vital role of the ascorbate transporter SVCT2. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2009;46:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spector R, Lorenzo AV. Ascorbic acid homeostasis in the central nervous system. Am J Physiol. 1973;225:757–763. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.4.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rice ME. Ascorbate regulation and its neuroprotective role in the brain. Trends in Neurosciences. 2000;23:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01543-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kratzing CC, Kelly JD. Tissue levels of ascorbic acid during rat gestation. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1982;52:326–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savini I, Rossi A, Pierro C, Avigliano L, Catani MV. SVCT1 and SVCT2: key proteins for vitamin C uptake. Amino Acids. 2008;34:347–355. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0555-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sotiriou S, Gispert S, Cheng J, Wang Y, Chen A, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Miller GF, Kwon O, Levine M, Guttentag SH, Nussbaum RL. Ascorbic-acid transporter Slc23a1 is essential for vitamin C transport into the brain and for perinatal survival. Nat Med. 2002;8:514–517. doi: 10.1038/0502-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison FE, Dawes SM, Meredith ME, Babaev VR, Li L, May JM. Low vitamin C and increased oxidative stress and cell death in mice that lack the sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter SVCT2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:821–829. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corpe CP, Tu H, Eck P, Wang J, Faulhaber-Walter R, Schnermann J, Margolis S, Padayatty S, Sun H, Wang Y, Nussbaum RL, Espey MG, Levine M. Vitamin C transporter Slc23a1 links renal reabsorption, vitamin C tissue accumulation, and perinatal survival in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1069–1083. doi: 10.1172/JCI39191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison FE, Meredith ME, Dawes SM, Saskowski JL, May JM. Low ascorbic acid and increased oxidative stress in gulo(−/−) mice during development. Brain Res. 2010;1349:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston CS, Thompson LL. Vitamin C status of an outpatient population. J Am Coll Nutr. 1998;17:366–370. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1998.10718777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madruga de Oliveira A, Rondo PH, Barros SB. Concentrations of ascorbic acid in the plasma of pregnant smokers and nonsmokers and their newborns. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2004;74:193–198. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.74.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stankova L, Riddle M, Larned J, Burry K, Menashe D, Hart J, Bigley R. Plasma ascorbate concentrations and blood cell dehydroascorbate transport in patients with diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 1984;33:347–353. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(84)90197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linster CL, Van Schaftingen E. Vitamin C. Biosynthesis, recycling and degradation in mammals. FEBS J. 2007;274:1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savini I, Rossi A, Catani MV, Ceci R, Avigliano L. Redox regulation of vitamin C transporter SVCT2 in C2C12 myotubes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon SJ, Wilson JX. Adaptive regulation of ascorbate transport in osteoblastic cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:675–681. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson JX, Jaworski EM, Kulaga A, Dixon SJ. Substrate regulation of ascorbate transport activity in astrocytes. Neurochem Res. 1990;15:1037–1043. doi: 10.1007/BF00965751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiao H, May JM. Development of ascorbate transporters in brain cortical capillary endothelial cells in culture. Brain Res. 2008;1208:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.02.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maeda N, Hagihara H, Nakata Y, Hiller S, Wilder J, Reddick R. Aortic wall damage in mice unable to synthesize ascorbic acid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:841–846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison FE, Yu SS, Van Den Bossche KL, Li L, May JM, McDonald MP. Elevated oxidative stress and sensorimotor deficits but normal cognition in mice that cannot synthesize ascorbic acid. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1198–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pachla LA, Kissinger PT. Analysis of ascorbic acid by liquid chromatography with amperometric detection. Methods Enzymol. 1979;62:15–24. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)62183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kratzing CC, Kelly JD, Kratzing JE. Ascorbic acid in fetal rat brain. J Neurochem. 1985;44:1623–1624. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb08804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berger UV, Hediger MA. The vitamin C transporter SVCT2 is expressed by astrocytes in culture but not in situ. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1395–1399. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200005150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice ME, Russo-Menna I. Differential compartmentalization of brain ascorbate and glutathione between neurons and glia. Neuroscience. 1998;82:1213–1223. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vannucci SJ, Clark RR, Koehler-Stec E, Li K, Smith CB, Davies P, Maher F, Simpson IA. Glucose transporter expression in brain: relationship to cerebral glucose utilization. Dev Neurosci. 1998;20:369–379. doi: 10.1159/000017333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagamatsu S, Sawa H, Nakamichi Y, Katahira H, Inoue N. Developmental expression of GLUT3 glucose transporter in the rat brain. FEBS Lett. 1994;346:161–164. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00455-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mun GH, Kim MJ, Lee JH, Kim HJ, Chung YH, Chung YB, Kang JS, Hwang YI, Oh SH, Kim JG, Hwang DH, Shin DH, Lee WJ. Immunohistochemical study of the distribution of sodium-dependent vitamin C transporters in adult rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:919–928. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amano A, Aigaki T, Maruyama N, Ishigami A. Ascorbic acid depletion enhances expression of the sodium-dependent vitamin C transporters, SVCT1 and SVCT2, and uptake of ascorbic acid in livers of SMP30/GNL knockout mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;496:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]