Abstract

Background and Purpose

Oxalobacter formigenes (OF) may play a protective role in preventing calcium oxalate stones. This is the first prospective study to evaluate the effect of antibiotics on OF colonization. Intestinal colonization by OF is associated with reduced urinary oxalate excretion. Exposure to antibiotics may be an important factor determining rates of colonization.

Materials and Methods

The effect of antibiotics on OF colonization was compared in two groups: A group receiving antibiotics for gastric infection with Helicobacter pylori (HP) and a group without HP whose members were not receiving antibiotics. OF colonization in stool was detected by oxalate degradation at baseline and after 1 and 6 months.

Results

The prevalence at baseline of intestinal colonization with OF was 43.1% among all patients screened. Among the 12 patients who were positive for OF who did not receive antibiotics, 11 (92%) had OF on stool tests at 1 month and 6 months. Of the 19 participants who were positive for OF and who received antibiotics for HP, only 7 (36.8%) continued to be colonized by OF on follow-up stool testing at 1 and 6 months (P=0.003 by Fisher exact test). Amoxicillin and clarithromycin caused 62.5% of subjects to become negative for OF at 1 month; 56.2% remained negative for OF at 6 months.

Conclusions

Antibiotics for HP infection effectively reduced colonization with OF, an effect present at 1 and 6 months after treatment. The lasting elimination of OF could be associated with hyperoxaluria and be a factor in recurrent kidney stone disease.

Introduction

Oxalobacter formigenes (OF) is a commensal bacterium that colonizes the human colon.1 These bacteria metabolize oxalate as their sole energy source and may play a protective role in preventing calcium oxalate kidney stones by reducing intestinal absorption of dietary oxalate,2 thereby decreasing the risk of hyperoxaluria. They may also stimulate oxalate secretion across the intestinal epithelium to further limit urinary oxalate excretion.3 Lack of colonization with OF is associated with hyperoxaluria4–6 and increased prevalence of kidney stones.7,8

A large proportion of the normal adult population is colonized with OF. A wide range of OF colonization rates is reported, varying from 38% to 60% in adults in the United States5,7 to 70% to 80% in adults elsewhere.9–11 The factors that contribute to such variable rates of colonization are unclear, although one potential risk factor is exposure to antibiotics. In one study, stool samples were collected for OF detection in patients who were consuming antibiotics; compared with controls, these patients were 70% less likely to have detectable stool OF.4 Prospective studies demonstrating that antibiotics eliminate OF colonization have not been performed.

OF strains are susceptible to quinolones, macrolides, tetracyclines, and metronidazole.12 Obtaining stool swabs from patients before antibiotic administration would be difficult because initiation of therapy is often indicated immediately and cannot be delayed. Treatment of endoscopically suspected gastric infection with Helicobacter pylori (HP), however, usually does not begin immediately, but is initiated days after the organism's presence is confirmed histologically. Because treatment regimens for HP usually include either clarithromycin or metronidazole, we chose to study patients who were being evaluated for HP infection to prospectively monitor intestinal OF colonization status.

This is the first controlled study to prospectively evaluate the influence of antibiotic administration on intestinal OF colonization.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective, unblinded controlled study in which patients who were undergoing upper endoscopy were recruited to participate. The indications for endoscopy and biopsy were determined by gastroenterologists, independent of this study. The prevalence of OF colonization was compared between an HP-positive group who were treated with antibiotics and an HP-negative control group who did not receive antibiotics.

Subjects were recruited from two gastroenterology practices: One at the New York Harbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VA), and the other at Bellevue Hospital (BH), the largest public hospital in New York City. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at VA and BH. Inclusion criteria required that participants were 18 years and older, and undergoing an upper endoscopy and determination of HP status for clinically indicated reasons.

Patients were excluded from endoscopy if they had coagulopathy, gastric varices, or gastric surgery. Those who had taken antibiotics within the past 2 years were excluded. Participants were asked to report any antibiotics other than those for HP during the study. If the first stool swabs at baseline did not demonstrate colonization with OF, patients were excluded from further participation.

Participation in the study did not affect the treatment regimen. Patients were treated for HP with standard effective regimens. The antibiotic regimen used was 10 to 14 days of either (a) amoxicillin 1 g twice a day, clarithromycin 500 mg twice a day, or (b) metronidazole 250 mg four times a day, bismuth 525 mg four times a day, and tetracycline 500 mg four times a day. A few patients received a different regimen than the others based on a history of penicillin allergy or intolerance of macrolides. All HP-positive participants were also treated with a proton pump inhibitor in accordance with established eradication regimens. Participants were compensated for their time and effort when the study was completed.

After upper endoscopy, stool swabs were obtained in all patients at baseline and before the initiation of antibiotics for HP eradication. Follow-up stool swabs were obtained in all participants at 1 and 6 months after the first set. The presence or absence of OF colonization was determined by an oxalate degradation assay.7 A collection kit was provided to participants at each sampling period to obtain four swabs from a single sample of stool. The swabs were collected at home, placed in transport tubes, and sent initially overnight to Ixion Biotechnology (Alachua, FL), and subsequently to Dr. Ross Holmes' laboratory at Wake Forest University (Winston-Salem, NC) when Ixion ceased business. The laboratories used identical procedures, obtained similar prevalence rates for OF colonization, and were blinded to treatment assignment.

Stool was cultured in selective liquid oxalate-containing medium for 10 days as reported elsewhere.7 Oxalate content of the medium was tested by adding CaCl2. Oxalate that is not metabolized, in the absence of OF, precipitates with added calcium and can be quantified by the OD600. This culture technique does not identify the organism directly but demonstrates stool oxalate degradation in a culture medium selective for OF.13

We planned a sample size of 25 participants in each study arm. The size was calculated to have an 80% probability of detecting a 35% reduction in OF colonization with antibiotic treatment compared with the untreated control group. The comparison was made by Fisher exact test with an alpha set at 0.05. A significant dropout rate led us to fall short of the planned sample size. Our significant result, however, led us to cease further enrollment.

Results

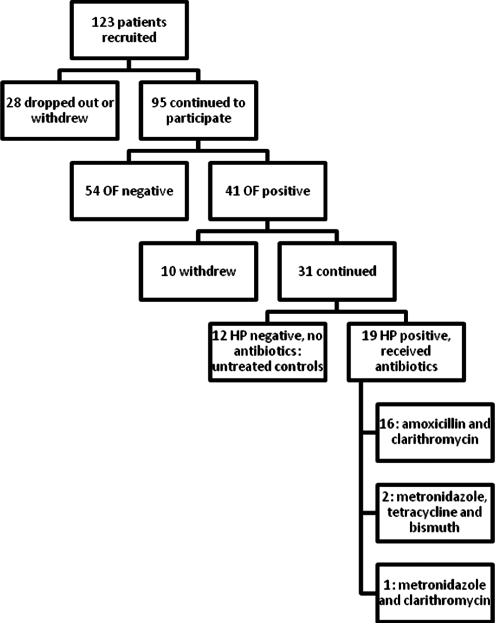

Figure 1 shows the flow of persons from enrollment through initial stool testing for OF, then HP testing with gastric biopsy, and subsequent antibiotic treatment, if indicated. Of 123 patients who were recruited to participate in the study, 28 dropped out before initial stool testing for OF. Dropouts from BH were mostly women.

FIG. 1.

Study participant flowchart.

Of the 95 remaining participants, 41(43.1%) had initial stool testing that was positive for OF. The prevalence at baseline of intestinal colonization with OF was 43.1% among all patients screened, 48% among participants recruited from the VA, and 31% among the participants from BH. Racial makeup of the subjects from the VA was 50% white, 34% black, 5% Asian, 11% undeclared or other. All participants from the VA were men. Among BH participants, there were 12 women and 14 men; the prevalence of intestinal colonization with OF was 25% among women and 36% among men. Participants from BH were 65% Latino, 19% black, 12% white, and 4% Asian; 59% men and 46% women. Of the participants who tested positive for OF on initial stool testing, 10 withdrew or were lost to follow-up.

Thirty men and 1 woman with intestinal colonization by OF on initial stool testing formed the study group who were followed prospectively and completed the study. Mean age was 64 years (range 40–84 y). Nineteen of these patients had a diagnosis of HP infection on gastric biopsy and needed antibiotic treatment as reported in Figure 1. The other 12 HP-negative patients did not need antibiotic therapy and served as untreated controls.

The results of initial and follow-up stool testing for OF are shown in Table 1. Among the control group of 12 patients who were positive for OF on initial stool testing and who were negative for HP and did not need antibiotic therapy, 11 (92%) continued to harbor OF on stool tests at 1 month and 6 months. In comparison, of the 19 participants who were positive for OF and who were administered antibiotic therapy for HP, only 7 (36.8%) continued to harbor OF on follow-up stool testing at 1 month and 6 months (P=0.003 by Fisher exact test at both time points). Six of these participants were consistently positive for OF in the stool at both follow-up time points. While one participant was positive for OF on stool testing at 1 month but cleared OF at 6 months, another participant who became negative for OF at 1 month was then positive for OF at 6 months.

Table 1.

Results of Stool Test for Oxalobacter Formigenes in Helicobacter Pylori Positive and Helicobacter Pylori Negative Participants at Baseline and Follow-up

| HP(+) treated with antibiotics+/total, (%) | HP(−) no antibiotic treatment+/total, (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 19/19 | 12/12 | |

| 1 Month | 7/19 (36.8) | 11/12 (91.7) | 0.003 |

| 6 Months | 7/19 (36.8) | 11/12 (91.7) | 0.003 |

One-tailed Fisher exact test.

HP=Helicobacter pylori.

Table 2 contains the results of testing broken down by antibiotic regimen, although most antibiotic-treated participants received amoxicillin and clarithromycin. Among participants who were treated with amoxicillin and clarithromycin, 62.5% became negative for OF at 1 month and 56.2% remained stool-negative for OF at 6 months. In the subset of two participants who were treated with tetracycline, metronidazole, and bismuth, 50% became stool-negative for OF at 6 months. The single participant who was treated with metronidazole and clarithromycin became negative for OF at 6 months.

Table 2.

Oxalobacter Formigenes Colonization According to Antibiotic Treatment Regimen

| Antibiotic regimen | Baseline % (+/total) | 1 Month % (+/total) | 6 Months % (+/total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin/clarithromycin | 100% (16/16) | 37.5% (6/16) | 43.8% (7/16) |

| Metronidazole/tetracycline/bismuth | 100% (2/2) | 50.0% (1/2) | 0% (0/2) |

| Metronidazole/clarithromycin | 100% (1/1) | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) |

Discussion

The importance of OF as a protective factor against stone disease is suggested but not proven by previous retrospective data. Studies performed to date have consistently suggested that OF colonization is less prevalent in participants with kidney stones.4,7,14 Elimination of OF colonization could lead to increased intestinal absorption of oxalate, resulting in hyperoxaluria and kidney stones. The ability of OF to stimulate enteral oxalate secretion is also suggested as a mechanism of its putative protective effect.3

No previous study has prospectively shown elimination of OF colonization after a course of antibiotics. Previous cross-sectional studies have shown that persons with a history of antibiotic use have lower colonization rates.4 Because longitudinal studies of OF colonization were lacking, it was possible that lower rates of colonization with OF were associated with higher rates of stones for reasons other than the organism's direct, causative effect on urine oxalate excretion.15 In this study, we have demonstrated for the first time that a course of antibiotics for a condition not related to nephrolithiasis is prospectively associated with a significant and persistent reduction in OF colonization. We chose HP eradication as a model because the initiation of a therapeutic antibiotic regimen is nonurgent and usually delayed, pending histologic evaluation of endoscopic specimens. This interval provided an opportunity for participants to be informed about the study, give consent, and provide a stool specimen before the administration of antibiotics. Such a protocol would not be possible if treating acute infectious processes, such as pneumonia, in which a delay in antibiotic administration would be undesirable, and the collection of a stool sample from an untreated study participant unlikely.

We demonstrated that treatment with a 2-week course of antibiotics for HP colonization was associated with a 63% elimination of colonization with OF 1 month after treatment with antibiotics; this elimination was persistent and still evident at 6 months. One participant who was positive for OF at baseline and at 1 month was negative at 6 months, while one of the control participants who was not treated with antibiotics lost OF positivity. At 6 months, only one of the participants whose colonization with OF was eliminated with antibiotics regained OF colonization. This finding supports the possibility that OF elimination after antibiotic exposure may be sustained and provide enough time for kidney stone formation. While it has previously been reported that detection of OF varies within stool collections, among stool collections performed on different days, and among individuals,16 our results were statistically significant while demonstrating consistent results at 1 month and 6 months in the control group whose members did not receive antibiotics.

OF is sensitive to a variety of antibiotics in common use for the treatment of a broad range of infections. These antibiotics include macrolides, such as erythromycin and clarithromycin, metronidazole, and doxycycline.12 In our study, most patients were treated for HP with metronidazole, clarithromycin, and bismuth preparations. Consistent with this finding, the lowest prevalence of OF colonization in one recent cross-sectional study was in patients who had, in the last 5 years, taken antibiotics to which OF was sensitive, including macrolides, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, rifampin, and metronidazole.17

We did not include measurement of urine oxalate in the study design. Serial measurements of oxalate excretion would best be performed in a situation in which diet could be controlled and the amount of oxalate and other nutrients ingested could be replicated. In a recent article by one of our group, there was no difference in urinary oxalate excretion between participants colonized and not colonized with OF unless they ingested a diet with low calcium and high oxalate content.18 Such a diet increases the intestinal luminal concentration of free oxalate, allowing for greater provision of the organism's substrate. In studying persons who were not selected for having hyperoxaluria, after elimination of colonization with OF there was a low likelihood of demonstrating a change in urinary oxalate, a highly variable measure under even well-controlled circumstances.19

We did not achieve our planned sample size in part because we found a lower prevalence of OF colonization than expected and ended the study. Because our interim analysis showed a strong difference between the groups, we terminated enrollment before reaching our planned sample size. Instead of the 70% rate of OF colonization on which we based our projections, we found that only 48% of our patients at the VA and 31% at BH had OF colonization. This result is similar to the rate found in another study in the United States that showed that 38% of nonstone-forming controls were positive for OF7 and there was 38% prevalence in another.17 These rates are lower than those reported elsewhere in the world, albeit in relatively small studies: 60% to 65% in India4,9 and 70% in children in Ukraine.10 Decreased prevalence of OF in American gastrointestinal tracts could contribute to high and rising prevalence rates of kidney stones.20 The increasing prevalence of stones could be related to increases in antibiotic use. In the United States from 1989 to 1999, there was a significant increase in use of extended-spectrum macrolides in comparison with penicillin and erythromycin for the treatment of sore throat by primary care physicians.21 This pattern could cause reductions in OF colonization, because clarithromycin was associated in our study with elimination of OF colonization. Notably, OF is also sensitive to even the more narrow-spectrum macrolide erythromycin.12

Subsequent study of the contribution of OF to stone disease should include longitudinal determination of the presence of colonization, and determination of the variables that contribute to rates of persistent vs transient colonization. The rate at which people become recolonized would be important to determine. Because current evidence suggests that newborns acquire OF through fecal-oral passage from their mothers, the ability of adult humans to be recolonized has not been demonstrated. In a recent article, the longer the interval since antibiotics, the higher the OF colonization rate, suggesting that recolonization occurs in subsequent years.17 One of the participants in our study who became OF negative 1 month after treatment with antibiotics became positive at 6 months. Only one study of two adults has demonstrated that it is possible to colonize an adult by oral administration of OF.12

Our study suggests that monitoring OF colonization after courses of antibiotics for any indication might be a clinically useful strategy, particularly in stone formers at risk for stone recurrence. The utility of testing might rely on a demonstration that administration of an OF preparation has clinical utility. Although effective in an animal model of primary hyperoxaluria, administration of OF has not yet been shown conclusively to be useful in the treatment of hyperoxaluria in humans, with studies ongoing.22,23 The ideal diet to prescribe in patients who are taking OF preparations would have to be defined. Restrictions in dietary calcium intake leads to more durable colonization of OF in rats, because it allows more free, noncomplexed oxalate to be available.6 A similar result has recently been shown in humans.18 Calcium restriction, however, has been repeatedly associated with increased stone prevalence both in epidemiologic studies and in a clinical trial.24,25 Furthermore, restriction of oxalate intake, as usually prescribed for stone formers, could be associated with reduced OF colonization as well. At present, determination of OF colonization status after a course of antibiotics cannot be recommended.

Abbreviations Used

- BH

Bellevue Hospital

- HP

Helicobacter pylori

- OF

Oxalobacter formigenes

- VA

Veterans Affairs

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grant K23CA107123 from the National Cancer Institute, and by grant 1UL1RR029893 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health (FF). Supported by unrestricted research funds from Amgen.

Disclosure Statement

Drs. Goldfarb and Francois are consultants for Takeda. The remaining authors have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Allison MJ. Cook HM. Milne DB, et al. Oxalate degradation by gastrointestinal bacteria from humans. J Nutr. 1986;116:455–460. doi: 10.1093/jn/116.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart CS. Duncan SH. Cave DR. Oxalobacter formigenes and its role in oxalate metabolism in the human gut. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;230:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatch M. Cornelius J. Allison M, et al. Oxalobacter sp. reduces urinary oxalate excretion by promoting enteric oxalate secretion. Kidney Int. 2006;69:691–698. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittal RD. Kumar R. Bid HK. Mittal B. Effect of antibiotics on Oxalobacter formigenes colonization of human gastrointestinal tract. J Endourol. 2005;19:102–106. doi: 10.1089/end.2005.19.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troxel SA. Sidhu H. Kaul P. Low RK. Intestinal Oxalobacter formigenes colonization in calcium oxalate stone formers and its relation to urinary oxalate. J Endourol. 2003;17:173–176. doi: 10.1089/089277903321618743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sidhu H. Schmidt ME. Cornelius JG, et al. Direct correlation between hyperoxaluria/oxalate stone disease and the absence of the gastrointestinal tract-dwelling bacterium Oxalobacter formigenes: Possible prevention by gut recolonization or enzyme replacement therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(suppl 14):S334–S340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufman DW. Kelly JP. Curhan GC, et al. Oxalobacter formigenes may reduce the risk of calcium oxalate kidney stones. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1197–1203. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittal RD. Kumar R. Mittal B, et al. Stone composition, metabolic profile and the presence of the gut-inhabiting bacterium Oxalobacter formigenes as risk factors for renal stone formation. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12:208–213. doi: 10.1159/000072285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar R. Mukherjee M. Bhandari M, et al. Role of Oxalobacter formigenes in calcium oxalate stone disease: A study from North India. Eur Urol. 2002;41:318–322. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidhu H. Enatska L. Ogden S, et al. Evaluating children in the Ukraine for colonization with the intestinal bacterium Oxalobacter formigenes, using a polymerase chain reaction-based detection system. Mol Diagn. 1997;2:89–97. doi: 10.1054/MODI00200089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwak C. Jeong BC. Kim HK, et al. Molecular epidemiology of fecal Oxalobacter formigenes in healthy adults living in Seoul, Korea. J Endourol. 2003;17:239–243. doi: 10.1089/089277903765444384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan SH. Richardson AJ. Kaul P, et al. Oxalobacter formigenes and its potential role in human health. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3841–3847. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.8.3841-3847.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allison MJ. Dawson KA. Mayberry WR. Foss JG. Oxalobacter formigenes gen. nov., sp. nov. Oxalate-degrading anaerobes that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Microbiol. 1985;141:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00446731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidhu H. Hoppe B. Hesse A, et al. Absence of Oxalobacter formigenes in cystic fibrosis patients: A risk factor for hyperoxaluria. Lancet. 1998;352:1026–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldfarb DS. Microorganisms and calcium oxalate stone disease. Nephron Physiol. 2004;98:48–54. doi: 10.1159/000080264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prokopovich S. Knight J. Assimos DG. Holmes RP. Variability of Oxalobacter formigenes and oxalate in stool samples. J Urol. 2007;178:2186–2190. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly JP. Curhan GC. Cave DR, et al. Factors related to colonization with Oxalobacter formigenes in U.S. adults. J Endourol. 2011;25:673–679. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang J. Knight J. Easter LH, et al. Impact of dietary calcium and oxalate, and oxalobacter formigenes colonization on urinary oxalate excretion. J Urol. 2011;186:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown JM. Stratmann G. Cowley DM, et al. The variability and dietary dependence of urinary oxalate excretion in recurrent calcium stone formers. Ann Clin Biochem. 1987;24:385–390. doi: 10.1177/000456328702400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stamatelou KK. Francis ME. Jones CA, et al. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976–1994. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1817–1823. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linder JA. Stafford RS. Antibiotic treatment of adults with sore throat by community primary care physicians: A national survey, 1989–1999. JAMA. 2001;286:1181–1186. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatch M. Gjymishka A. Salido EC, et al. Enteric oxalate elimination is induced and oxalate is normalized in a mouse model of primary hyperoxaluria following intestinal colonization with Oxalobacter. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G461–G469. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00434.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoppe B. Beck B. Gatter N, et al. Oxalobacter formigenes: A potential tool for the treatment of primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1305–1311. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curhan GC. Willett WC. Rimm EB. Stampfer MJ. A prospective study of dietary calcium and other nutrients and the risk of symptomatic kidney stones. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:833–838. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303253281203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borghi L. Schianchi T. Meschi T, et al. Comparison of two diets for the prevention of recurrent stones in idiopathic hypercalciuria. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:77–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]