Abstract

Activation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), production of angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7)] and stimulation of the Ang-(1–7) receptor Mas exert beneficial actions in various peripheral cardiovascular diseases, largely through opposition of the deleterious effects of angiotensin II via its type 1 receptor. Here we considered the possibility that Ang-(1–7) may exert beneficial effects against CNS damage and neurological deficits produced by cerebral ischaemic stroke. We determined the effects of central administration of Ang-(1–7) or pharmacological activation of ACE2 on the cerebral damage and behavioural deficits elicited by endothelin-1 (ET-1)-induced middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), a model of cerebral ischaemia. The results of the present study demonstrated that intracerebroventricular infusion of either Ang-(1–7) or an ACE2 activator, diminazine aceturate (DIZE), prior to and following ET-1-induced MCAO significantly attenuated the cerebral infarct size and neurological deficits measured 72 h after the insult. These beneficial actions of Ang-(1–7) and DIZE were reversed by co-intracerebroventricular administration of the Mas receptor inhibitor, A-779. Neither the Ang-(1–7) nor the DIZE treatments altered the reduction in cerebral blood flow elicited by ET-1. Lastly, intracerebroventricular administration of Ang-(1–7) significantly reduced the increase in inducible nitric oxide synthase mRNA expression within the cerebral infarct that occurs following ET-1-induced MCAO. This is the first demonstration of cerebroprotective properties of the ACE2–Ang-(1–7)–Mas axis during ischaemic stroke, and suggests that the mechanism of the Ang-(1–7) protective action includes blunting of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression.

The major renin–angiotensin system (RAS) product, the octapeptide angiotensin II (Ang II), has been shown to have an important causative role in many cardiovascular diseases, including a major deleterious function in the processes that lead to CNS damage following cerebral ischaemia (Saavedra, 2005). The specific intracerebral mechanisms by which Ang II exerts harmful effects following stroke remain elusive, but it is clear that Ang II type 1 receptors (AT1R) are involved. This has been confirmed by numerous studies, which have shown that blockade of AT1R via angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) decreases cerebral cortical/subcortical infarct size and the ensuing neurological deficits in animal models of stroke (Dai et al. 1999; Nishimura et al. 2000; Groth et al. 2003). In addition, ARBs reduce cardiovascular risk and improve stroke prevention in human clinical trials (Thöne-Reineke et al. 2006).

In contrast to the harmful cardiovascular actions of Ang II via AT1R, a growing body of evidence indicates that another product of the RAS, the heptapeptide angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7)], exerts beneficial actions in various cardiovascular diseases (Santos et al. 2008; Ferreira et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2011). Angiotensin-(1–7) is generated predominately from Ang II by angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), and exerts physiological effects in the brain mediated by its receptor, Mas (Santos et al. 2003; Becker et al. 2007; Dupont & Brouwers, 2010). Together, these components make up the ACE2–Ang-(1–7)–Mas axis, which counteracts a number of the physiological and pathophysiological effects of Ang II via the AT1R in the cardiovascular system (Benter et al. 2007; Santos et al. 2008; Feng et al. 2010). Thus, many studies targeting this axis have revealed its broad therapeutic potential for the treatment of hypertension, high blood pressure-related pathology, myocardial infarction and heart failure (Castro-Chaves et al. 2010). Furthermore, the cardiovascular protective effects offered by ARB therapy may also be due in part to ACE2–Ang-(1–7)–Mas axis activation, because multiple human and animal studies have shown that ARB treatment increases ACE2 expression and production of Ang-(1–7) (Ferreira et al. 2010).

Considering that Ang-(1–7) counters many of the harmful contributions of Ang II/AT1R in cardiovascular diseases, we considered the possibility that this peptide may have a beneficial effect against CNS damage and deficits produced by cerebral ischaemic stroke. Indeed, endogenous ACE2 and Mas are present within the brain, including the cerebral cortex (Metzger et al. 1995; Doobay et al. 2007). Based on the above evidence, we developed the general hypothesis that Ang-(1–7) has the ability to exert a Mas-mediated cerebroprotective action during ischaemic stroke. In a previous study, we have validated the endothelin-1 (ET-1)-induced middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model of cerebral ischaemia for examination of the brain RAS in stroke (Mecca et al. 2009). Here, the main aim was to determine whether central administration of Ang-(1–7) or pharmacological activation of ACE2 attenuates the cerebral damage and neurological deficits produced by ET-1-induced ischaemia.

Methods

Ethical approval

For the experiments described here, we used a total of 168 adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–275 g) purchased from Charles River Farms (Wilmington, MA, USA). All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. In addition, the principles governing the care and treatment of animals, as stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (publication no. 85–323, revised 1996) and adopted by the American Physiological Society, were followed at all times during this study. Rats had ad libitum access to water and standard rat chow and were housed in a well-ventilated, specific pathogen-free, temperature-controlled environment (24 ± 1°C; 12 h–12 h light–dark cycle).

Surgical procedures

Implantation of intracranial cannulae

After a 7 day acclimation period, rats were anaesthetized with a mixture of O2 (1.5 L min−1) and 4% isoflurane and placed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame, and anaesthesia was maintained for the duration of surgery using an O2–isoflurane (2%) mixture delivered through a nose-cone attached to the frame. Animals then underwent two intracranial operations essentially as detailed previously (Mecca et al. 2009). Body temperature and the level of anaesthesia were measured throughout these procedures, the latter monitored by assessing hindlimb withdrawal following toe pinch. First, placement of a stainless-steel 21-gauge guide cannula [4 mm long; for ET-1 injections adjacent to the middle cerebral artery (MCA)] into the right cerebral hemisphere, using the following stereotaxic co-ordinates: 1.6 mm anterior and 5.2 mm lateral to bregma. Second, implantation into the left cerebral ventricle (1.3 mm posterior and 1.5 mm lateral to bregma, 4.5 mm below the surface of the cranium) of a stainless-steel cannula (kit 1,; ALZET, Cupertino, CA, USA) coupled via vinyl tubing to a 2 week osmotic pump (model 2002; ALZET; Fleegal & Sumners, 2003; Grobe et al. 2007). Osmotic pumps were implanted subcutaneously between the scapulae and were used to infuse Ang-(1–7), diminazine aceturate (DIZE), (D-Ala7)-angiotensin-(1–7) (A-779) or control solutions [artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) for Ang-(1–7) and A-779 or water for DIZE] into the left lateral cerebral ventricle starting at the time of intracerebroventricular (I.C.V.) cannula placement and lasting until the animals were killed. Following this surgery, the wound was closed and an analgesic agent was administered to the rat (buprenorphine; 0.05 mg kg−1 S.C; Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) before waking.

Endothelin-1-induced middle cerebral artery occlusion

Seven days after placement of intracranial cannulae, rats were anaesthetized as before, placed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame and underwent MCAO via intracranial injection of ET-1 (3 μl of 80 μM solution; 1 μl min−1) through the guide cannula (17.2 mm below the top of the cannula), adjacent to the MCA (Mecca et al. 2009). Body temperature and the level of anaesthesia were measured throughout this procedure. In previous studies, we validated this procedure for investigating the role of the brain RAS in ischaemic stroke (Mecca et al. 2009).

Visualization of MCA branches and analysis of vessel diameter

These procedures were performed as detailed by us previously (Mecca et al. 2009). In brief, rats were anaesthetized as before, after which a temporal craniectomy was performed to visualize the primary and secondary branches of the MCA. An approximately 3–4 mm square piece of bone was removed from the left squamous portion of the temporal bone immediately caudal to the orbit. The dura was left in place, and debris was cleared away using sterile 0.9% saline. Next, ET-1-induced MCAO was performed as described in the previous subsection except that the needle was left in place until all images were captured so that the focal plane would not be disturbed. The cerebral cortex and associated vessels visible through this cranial window were imaged using a Moticam 1000 digital camera (Motic, Richmond, BC, Canada) coupled to a Revelation surgical microscope (Seiler Instrument and Manufacturing, St Louis, MO, USA). Vessel diameter was determined by averaging one primary and two secondary MCA branches per rat window using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) by an individual who had been blinded to the nature of the treatment. A baseline image was captured prior to ET-1 injection, and subsequent images were captured each 1 min interval for 40 min. Vessel diameter at each time point was normalized to the baseline vessel diameter so that comparisons could be made using multiple MCA branches of several rats.

Cerebral blood flow monitoring

Laser Doppler flowmetry was used to measure cerebral blood flow (CBF) prior to and lasting for 1 h after ET-1 injection. Rats were anaesthetized with isoflurane as before and placed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame as described above. Cerebral blood flow measurements were performed using a Standard Pencil Probe and Blood Flow Meter coupled to a Powerlab 4/30 with LabChart 7 (ADInstruments, Inc., Colorado Springs, CO, USA). The probe was placed either just posterior to the MCA guide cannula at the lateral skull ridge (for ischaemic penumbra analyses), or 1.6 mm anterior to bregma and on the lateral skull surface (for ischaemic core recordings). Body temperature and the level of anaesthesia were measured throughout this procedure. Data were recorded in arbitrary blood perfusion units at 1000 Hz. Baseline CBF was calculated by averaging a 1 min interval immediately prior to ET-1 injection. Changes in CBF were calculated as a percentage of baseline by averaging a 10 s interval every 1 min, or a 1 s interval every 1 s.

Indirect blood pressure monitoring

Blood pressure was recorded via an indirect tail-cuff method as described previously (Grobe et al. 2007).

Neurological testing

Rats from each treatment group underwent neurological testing 72 h following the ET-1-induced MCAO (Mecca et al. 2009). Neurological evaluations were performed using two separate scoring scales reported by Bederson et al. (1986) and Garcia et al. (1995), which cumulatively evaluate spontaneous activity, symmetry in limb movement, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, response to vibrissae touch, resistance to lateral push and circling behaviour. Additionally, animals were evaluated for neurological deficits using a sunflower seed-eating test (Gonzalez & Kolb, 2003), which provides an index of fine motor function. In this test, rats are timed while opening five sunflower seeds, and the number of shell pieces is recorded. Rats with less neurological impairment open the five seeds faster and more efficiently by breaking the shell into fewer pieces to accomplish the task.

Intracerebral infarct size

Following neurological testing, all rats were killed by inducing deep anaesthesia with a mixture of O2 (1.5 L min−1) and 4% isoflurane, followed by decapitation. Brains were removed and 2 mm coronal sections cut through the cortical and subcortical infarct zones for the following analyses. Infarct volume was assessed in brain sections by staining with 0.05% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) for 30 min at 37°C (Mecca et al. 2009). Tissue ipsilateral to the occlusion, which was not stained, was assumed to be infarcted. After fixation with 10% formalin, brain sections were scanned on a flatbed scanner (Canon) and analysed using ImageJ software (NIH). To compensate for the effect of brain oedema, the corrected infarct volume was calculated using an indirect method (Kagiyama et al. 2004).

Analyses of mRNA

These were performed using the whole ipsilateral (ET-1 injection side) cerebral hemisphere, or a coronal section immediately caudal to the slice used for TTC staining, containing the infarcted cerebral cortex. Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Isolated RNA underwent DNAse I treatment to remove genomic DNA. Mas, AT1R, ACE2, interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1α (IL-1α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) mRNA was analysed via real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) in a PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as detailed by us previously (Li et al. 2008). Oligonucleotide primers and TaqMan probes specific for the above genes were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Data were normalized to 18S rRNA.

Immunohistochemistry of NeuN

A subset of the experimental rats was used for immunostaining for the neuron-specific marker, NeuN, a DNA binding protein that is present in nuclei, perikarya and some processes. Seventy-two hours following ET-1 or sham injections, rats were killed by induction of deep anaesthesia with a mixture of O2 (1.5 L min−1) and 4% isoflurane, followed by decapitation. Brains were removed and frozen fresh in Optimal Cutting Temperature tissue embedding medium (OCT; Sakura Finetech, Torrance, CA, USA) for NeuN as follows. Brain sections corresponding to the sections used for TTC staining were cut at 5 or 10 μm thickness from fresh-frozen tissue blocks and air dried at room temperature overnight. The OCT was removed in a wash of 1× Tris Buffered Saline (TBS) for 5 min. Slides were drained and wiped, then blocked for 1 h in 2% horse serum diluted in 1× TBS. Slides were wiped, and blocking buffer was replaced with primary mouse anti-NeuN antibody (1:100 dilution), and incubated overnight at 4°C. Following two 5 min washes in TBS, Alexafluor donkey anti-mouse 488 (1:500 dilution) was added to the slides. After a 45 min incubation at room temperature, slides were again double washed in TBS. Sections were then postfixed for 5 min in 10% neutral buffered formalin, washed twice more, then wiped dry before mounting in DAPI Vectashield.

Chemicals

Angiotensin-(1–7) and A-779 were purchased from Bachem Bioscience (Torrance, CA, USA). Diminazine aceturate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Endothelin-1 was from American Peptide Company, Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Mouse anti-NeuN was from Millipore (Bedford, MA, USA). Alexafluor donkey anti-mouse 488 was from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA). All other chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Data analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated, as specified in the figure legends, with the use of a Kruskal–Wallis test, two-way row-matched ANOVA, one-way ANOVA or Student’s unpaired t test, as well as with Dunn’s multiple comparison test, the Bonferroni test, Newman–Keuls test or the Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test for post hoc analyses when appropriate. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. Individual P values are noted in the results and figure legends.

Results

Endothelin-1-induced MCAO and intracerebral damage: attenuation by Ang-(1–7) via a Mas-mediated mechanism

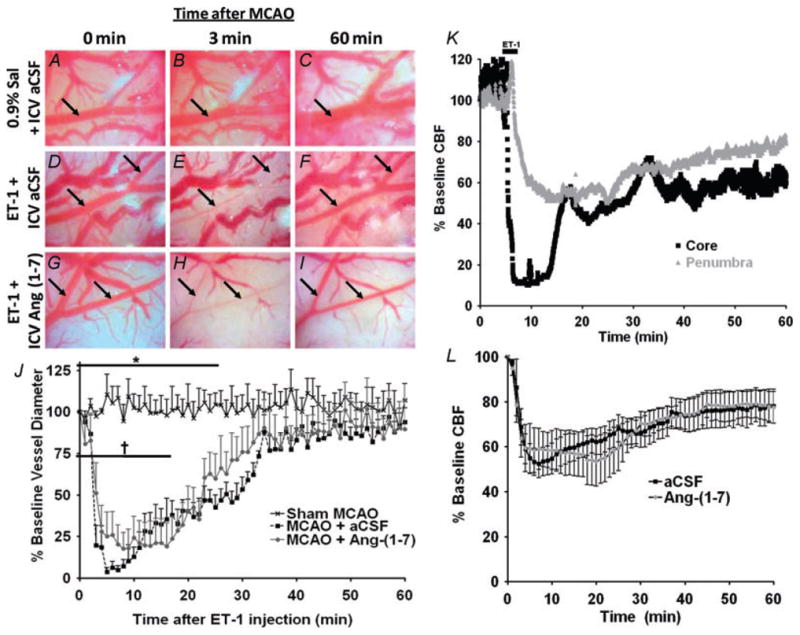

In previous experiments, we demonstrated that injection of ET-1 adjacent to the MCA produces effective constriction of this vessel and significant ischaemic damage to the cerebral cortex and striatum on the injected side of the brain (Cao et al. 2009; Mecca et al. 2009), consistent with other studies (Sharkey et al. 1993). In the present set of experiments, we used an identical approach to elicit MCAO and CNS damage in normal Sprague–Dawley rats, and investigated the potential cerebroprotective actions of Ang-(1–7) applied via the I.C.V. route. In Sprague–Dawley rats that had been infused I.C.V. with aCSF [vehicle for Ang-(1–7); 0.5 μl h−1] for 7 days, injection of 3 μl of 80 μM ET-1 adjacent to the MCA produced a rapid and very significant constriction of this vessel, when compared with rats that underwent sham MCAO (injection of 3 μl of 0.9% saline adjacent to the MCA; Fig. 1A–F and J). The constrictor action of ET-1 was transient, with MCA vessel diameter returning to baseline values within 40–50 min (Fig. 1J). Consistent with the vasoconstrictor action of ET-1, laser Doppler flowmetry analyses using a separate group of rats revealed that similar intracranial application of this peptide produced a dramatic (~90%) reduction of CBF at the ischaemic core, and an ~60% reduction in CBF at the ischaemic penumbra (Fig. 1K and L). The ET-1-induced reduction in CBF began to reverse within 10–20 min, but CBF had not returned to baseline by 60 min after the injection (Fig. 1K and L). As our goal was to test the effects of Ang-(1–7) on ET-1-induced intracerebral damage, it was important first to evaluate whether central administration of this peptide altered the effects of ET-1 on cerebral vasoconstriction and CBF. Pretreatment of rats for 7 days with Ang-(1–7) (1.1 nM; 0.5 μl h−1) via I.C.V. infusion did not alter either the MCA constriction or the reduction in CBF induced by ET-1 (Fig. 1G–J and L). The dose of Ang-(1–7) used was based on the concentration of this peptide that was shown to increase bradykinin and nitric oxide levels in the brain following stroke (Zhang et al. 2008). In addition, I.C.V. infusion of Ang-(1–7) as above did not alter systolic blood pressure during the time course of the experiment. For example, systolic blood pressures were 114 ± 7 and 117 ± 1 mmHg after 7 and 14 days of Ang-(1–7) infusion, respectively, versus 116 ± 3 and 117 ± 3 mmHg, respectively, in the rats infused with aCSF at the same time points (n = 6 rats in each group).

Figure 1. Effects of angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7)] on endothelin-1 (ET-1)-induced middle cerebral artery (MCA) constriction and cerebral blood flow.

A–I are photomicrographs showing the MCA branches (arrows) during 80 μM ET-1-induced vasoconstriction. Primary and secondary branches of the MCA were visualized with a surgical microscope after temporal craniotomy to create a cranial window. Images were captured at a rate of 1 min−1, starting immediately prior to ET-1 injection (0 min), throughout the ET-1 injection (3 min) and for at least 60 min after initiation of the ET-1 injection. Representative images are shown for rats that underwent 7 days of intracerebroventricular (I.C.V.) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) pretreatment (0.5 μl h−1) prior to a sham middle cerebral artery occlusion [MCAO; 3 μl of 0.9% saline (Sal) injection, A–C], 7 days of I.C.V. aCSF pretreatment (0.5 μl h−1) prior to an ET-1-induced MCAO (3 μl of 80 μM ET-1 injection, D–F), or 7 days of I.C.V. Ang-(1–7) (1.1 nM; 0.5 μl h−1) pretreatment prior to an ET-1-induced MCAO (G–I). J shows vasoconstriction of primary or secondary MCA branches quantified as the percentage of baseline vessel diameter. Data are means ± SEM from four rats per treatment condition. Baseline vessel diameter was determined prior to ET-1 or 0.9% saline injection (time 0 min). *P < 0.05 for aCSF versus sham MCAO and †P < 0.05 for Ang-(1–7) versus sham MCAO [two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (P < 0.001) followed by Bonferroni post hoc test]. K shows cerebral blood flow (CBF) in the ischaemic core and penumbra during ET-1-induced (MCAO). Laser Doppler flowmetry was used to investigate the CBF reduction that results in cortical areas both adjacent (ischaemic core) and distal (ischaemic penumbra) to the site of ET-1 (80 μM) injection. Representative traces from one rat are shown for each probe position. The data are presented as a percentage of the baseline signal. L shows the effects of I.C.V. infusion of Ang-(1–7) on CBF in the vascular territory of the MCA distal to the site of ET-1 injection. Data are means ± SEM of the percentage change from baseline CBF. Endothelin-1 injection took place over a period of 3 min starting at 0 min on this graph. No significant differences exist between Ang-(1–7) (n = 6) and aCSF (n = 6) treatment groups at any time point (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA).

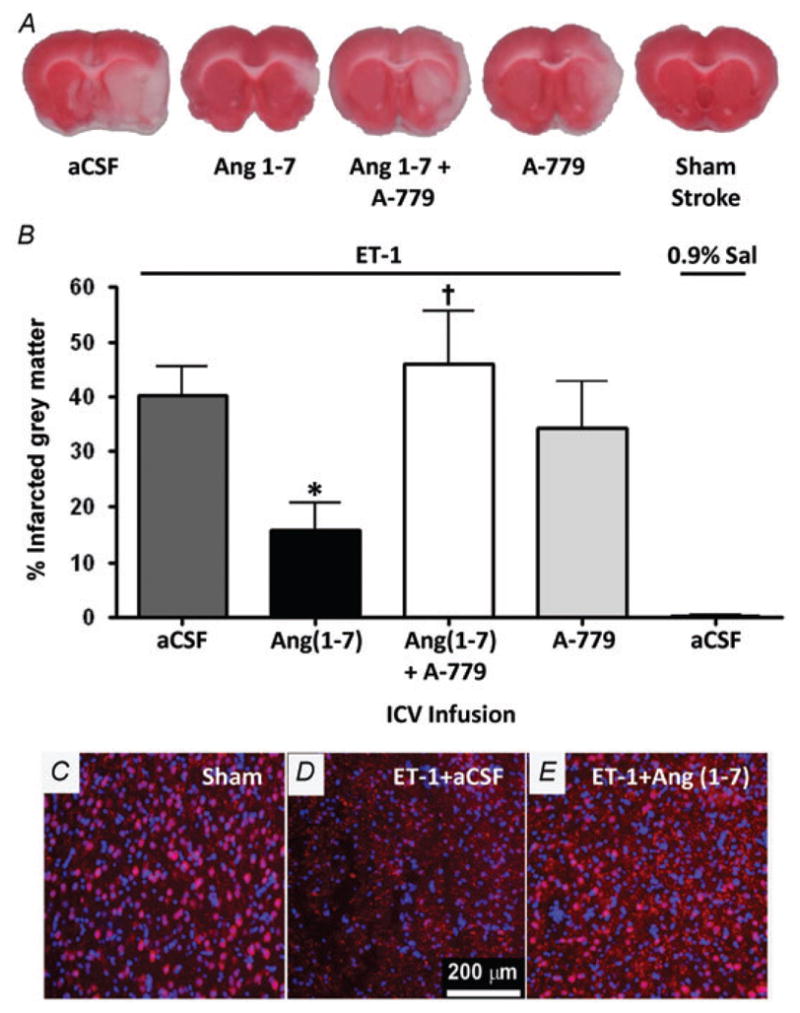

Intracerebroventricular infusion of Ang-(1–7) (1.1 nM; 0.5 μl h−1) into rats for 7 days prior to ET-1-induced MCAO and continuing for 3 days post-MCAO produced a significant decrease in the cerebral infarct size (measured 3 days following ET-1 application) when compared with rats that had received I.C.V. infusion of the control vehicle aCSF. This is illustrated by the representative TTC-stained coronal brain sections in Fig. 2A and the data showing the percentage infarcted grey matter in Fig. 2B. Rats that had received a sham stroke did not exhibit any noticeable cerebral damage according to TTC staining (Fig. 2A and B). The Ang-(1–7)-induced decrease in cerebral infarct size was reversed by co-infusion of the Mas antagonist A-779 (1.14 nM; 0.5 μl h−1, I.C.V.) along with Ang-(1–7). Pretreatment of rats with an I.C.V. infusion of A-779 alone did not significantly modify the ET-1-induced cerebral damage (Fig. 2A and B). The protective action of Ang-(1–7) following ET-1-induced MCAO was also demonstrated qualitatively through immunostaining for the neuron specific marker, NeuN. Rats that had received a sham stroke displayed abundant NeuN-immunopositive (pink) cells in the cerebral cortex, as expected (Fig. 2C). In contrast, there were few intact NeuN-immunopositive cells in the cerebral cortical infarct zone of rats that had undergone ET-1-induced MCAO (Fig. 2D). However, intact NeuN-immunopositive cells were clearly visible in the cerebral cortical infarct zone of rats that had undergone I.C.V. infusion of Ang-(1–7) as above during ET-1-induced MCAO (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2. Intracerebral pretreatment with Ang-(1–7) reduces CNS infarct size after ET-1-induced MCAO.

Rats were pretreated via the I.C.V. route with Ang-(1–7) (1.1 nM; 0.5 μl h−1; n = 9), aCSF (n = 23), Ang-(1–7) + A-779 (1.14 nM; 0.5 μl h−1; n = 9) or A-779 (n = 7) alone for 7 days prior to MCAO induced by intracranial injection of ET-1 as described in the Methods. In addition, two rats received a sham MCAO with 0.9% saline injection in place of ET-1. Brains were removed for TTC staining 72 h after the ET-1-induced MCAO. A, representative brain sections showing infarcted (white) and non-infarcted grey matter (red) in the treatment conditions indicated. B, bar graphs are means + SEM showing the percentage infarcted grey matter in each treatment group. *P < 0.05 versus aCSF; †P < 0.05 versus Ang-(1–7). C, D and E are representative fluorescence micrographs showing NeuN immunoreactivity co-localized with DAPI nuclear stain (pink coloured cells; red NeuN + blue DAPI) in the cerebral cortex of rats that underwent sham stroke surgery, ET-1-induced MCAO + I.C.V. infusion of aCSF (0.5 μl h−1; 7 days) or ET-1-induced MCAO + I.C.V. infusion of Ang-(1–7) (1.1 nM; 0.5 μl h−1; 7 days).

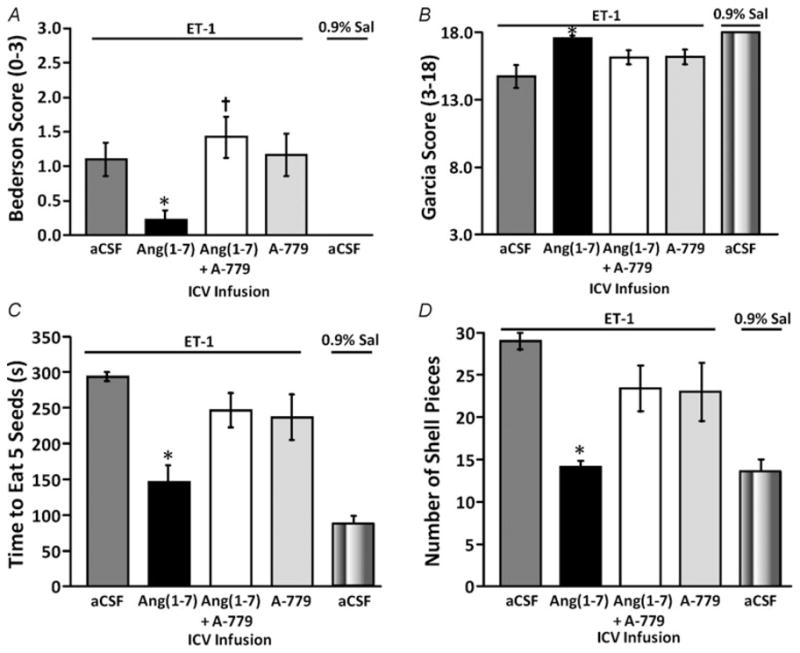

Endothelin-1-induced behavioural deficits: attenuation by central administration of Ang-(1–7) via a Mas-mediated mechanism

In addition to the gross and histological evidence for cerebroprotection, central pretreatment with Ang-(1–7) attenuated the neurological deficits attributable to ET-1-induced MCAO. For example, at 72 h following ET-1 induced MCAO, there were significant behavioural deficits in rats that had been pretreated with aCSF (I.C.V. infusion for 7 days), according to the Bederson examination (score >0) and the Garcia examination (score <18; Fig. 3A and B). No such deficits were observed in rats that underwent sham MCAO (0.9% saline instead of ET-1 injection; Fig. 3A and B). Intracerebroventricular pretreatment of rats for 7 days with Ang-(1–7) (1.1 nM; 0.5 μl h−1) prior to ET-1-induced MCAO significantly reduced the Bederson examination score compared with the aCSF pretreated control group (Fig. 3A). This effect of Ang-(1–7) was reversed by co-infusion of A-779 (1.14 nM; 0.5 μl h−1, I.C.V.; Fig. 3A). This cerebroprotective action of I.C.V.-infused Ang-(1–7) was also observed through a significantly improved Garcia examination score compared with the aCSF-pretreated control group, an effect that was diminished by co-infusion with A-779 (Fig. 3B). Pretreatment with an I.C.V. infusion of A-779 alone resulted in both Bederson and Garcia examination scores that were similar to the score for aCSF pretreatment. Utilization of a sunflower seed-eating task allowed for further evaluation of neurological function and provided strong evidence for the cerebroprotective properties of Ang-(1–7) during focal cerebral ischaemia. Rats were given five whole sunflower seeds and then timed while manipulating and opening the shells to eat the seeds. Those animals with significant neurological deficits display longer latency to remove the shell and break it into many small pieces. Rats that underwent ET-1-induced MCAO during I.C.V. infusion of aCSF exhibited a longer time to eat the five seeds and broke the shell into more pieces when compared with rats that had a sham stroke (Fig. 3C and D), consistent with our previous findings (Mecca et al. 2009). Intracerebroventricular pretreatment of rats for 7 days with Ang-(1–7) prior to ET-1-induced MCAO elicited significant reductions in the time required to eat five sunflower seeds and in the number of shell pieces compared with an aCSF-pretreated control group, effects that were reversed when Ang-(1–7) was co-infused with A-779 (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3. Intracerebral pretreatment with Ang-(1–7) reduces behavioural deficits 72 h after ET-1-induced MCAO.

Rats were pretreated via the I.C.V. route with Ang-(1–7) (1.1 nM; 0.5 μl h−1; n = 9), aCSF (n = 23), Ang-(1–7) + A-779 (1.14 nM; 0.5 μl h−1; n = 9) or A-779 (n = 7) alone for 7 days prior to ET-1-induced MCAO, as described in the Methods. The bar graphs shown here are the means ± SEM of data obtained from the Bederson neurological examination (A) and the Garcia neurological examination (B), as well as the sunflower seed-eating test for the time to eat five seeds (C) and the number of shell pieces (D). Also shown in each panel are data from two rats that underwent I.C.V. infusion of aCSF as above and a sham stroke (0.9% saline injection instead of ET-1). *P < 0.01 versus aCSF/ET-1 group; †P < 0.01 versus Ang-(1–7) group.

Endothelin-1-induced MCAO, intracerebral damage and behavioural deficits: attenuation by central administration of an ACE2 activator

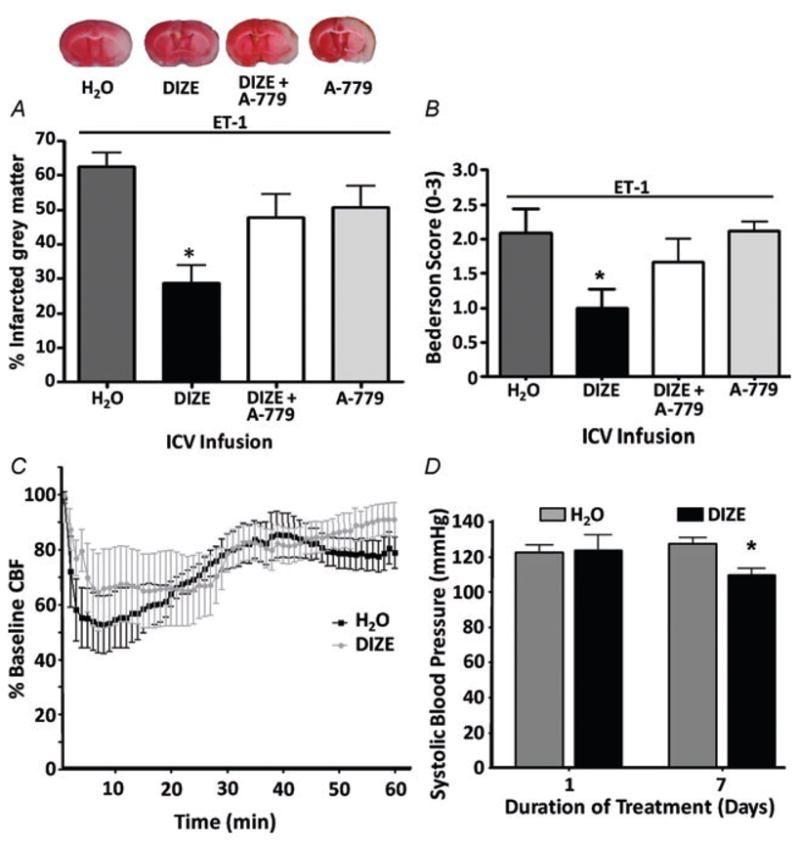

Endogenous Ang-(1–7) is generated predominately from Ang II catalysed by ACE2 (Tipnis et al. 2000). Thus, in the next set of experiments we tested whether pharmacological activation of ACE2 in the brain would elicit cerebroprotective actions following ET-1-induced MCAO, similar to the beneficial effects of Ang-(1–7). For these studies, we used DIZE, a small-molecule antiprotozoal agent (Peregrine & Mamman, 1993) that shares structural similarity with XNT (1-[(2-dimethylamino) ethylamino]-4-(hydroxymethyl)-7-[(4-methylphenyl) sulfonyl oxy]-9H-xanthene-9-one), another ACE2 activator (Hernández Prada et al. Hypertension, 2008) and has recently been described to increase ACE2 activity (Gjymishka et al. 2010). Central pretreatment of rats for 7 days with DIZE (5 μg (0.5 μl)−1 h−1, I.C.V.) prior to ET-1-induced MCAO significantly reduced the intracerebral infarct size compared with a control group that was pretreated with I.C.V. infusion of water (0.5 μl h−1; DIZE solvent; Fig. 4A). The length of treatment was designed to determine the effectiveness of DIZE before, during or after stroke. The DIZE-induced cerebroprotection was reversed by co-infusion of the Mas receptor antagonist, A-779 (1.14 nM; 0.5 μl h−1, I.C.V.), whereas I.C.V. infusion of A-779 alone did not significantly modify the ET-1-induced cerebral damage compared with water pretreatment (Fig. 4A). In addition to the gross histological evidence for cerebroprotection induced by DIZE, central pretreatment with this compound attenuated the neurological deficits attributed to ET-1-induced MCAO. For example, 72 h following ET-1-induced MCAO there were significant behavioural deficits in rats that had been pretreated with water (I.C.V. infusion for 7 days), according to the Bederson examination (score >0). Central pretreatment of rats for 7 days with DIZE (5 μg (0.5 μl)−1 h−1, I.C.V.) prior to ET-1-induced MCAO significantly reduced the Bederson examination score compared with the water-pretreated control group, an effect that was reversed by co-infusion of DIZE with A-779 (1.14 nM; 0.5 μl h−1, I.C.V.; Fig. 4B). Pretreatment with an I.C.V. infusion of A-779 alone resulted in Bederson examination scores which were similar to the score for water pretreatment (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Intracerebral pretreatment with diminazine aceturate (DIZE) reduces CNS infarct size and behavioural deficits after ET-1-induced MCAO.

Rats were pretreated via the I.C.V. route with water (DIZE solvent; n = 15), DIZE (5 μg (0.5 μl)−1 h−1); n = 18), DIZE + A-779 (1.14 nM; 0.5 μl h−1; n = 7) or A-779 (n = 10) alone for 7 days prior to MCAO induced by intracranial injection of ET-1 (80 μM). A, brains were removed for TTC staining 72 h after stroke. Representative brain sections (top) show infarcted (white) and non-infarcted grey matter (red) in the above-described treatment conditions. Bar graphs (bottom) are means + SEM showing the percentage infarcted grey matter in each treatment group. *P < 0.001 versus water. B, bar graphs are means + SEM showing the Bederson examination scores in each treatment condition, 72 h following the ET-1-induced MCAO. *P < 0.05 versus water. C, effects of I.C.V. infusion of DIZE (5 μg (0.5 μl)−1 h−1) on CBF in the vascular territory of the MCA distal to the site of ET-1 injection. Data are means ± SEM of the percentage change from baseline CBF. Endothelin-1 injection took place over a period of 3 min starting at 0 min. No significant differences exist between DIZE (n = 6) and water (n = 6) treatment groups at any time point (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA). D, effects of I.C.V. infusion of DIZE (5 μg (0.5 μl)−1 h−1) on systolic blood pressure. Bar graphs are means + SEM (n = 6 rats per group). *P < 0.01 versus water.

When compared with the rats that were pretreated with water, pretreatment with DIZE via the I.C.V. route did not significantly alter the reduction in CBF induced by ET-1, according to laser Doppler flowmetry (Fig. 4C). This is important because it demonstrates that the beneficial action of DIZE is not simply via offsetting the constrictor action of ET-1. Interestingly, I.C.V. infusion of DIZE produced a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure after 7 days of treatment (Fig. 4D).

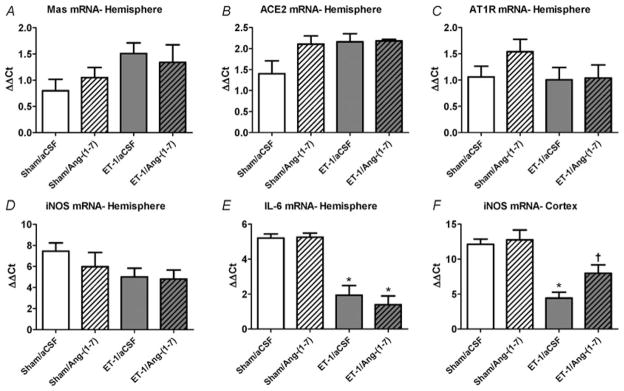

Angiotensin-(1–7)-induced cerebroprotection: role of iNOS

It is known that ACE2 activation or Ang-(1–7) by itself can induce various protective mechanisms, including effects on RAS genes, such as Mas and AT1R (Feng et al. 2010). Furthermore, it is also known that pro-inflammatory cytokines are induced in the cerebral infarct zone following ischaemia and increase inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression, leading to neuronal damage (Rothwell & Relton, 1993; Iadecola & Ross, 1997; Moro et al. 2004; Jin et al. 2010). Thus, in an initial set of experiments we tested the effects of ET-1-induced stroke, in the absence and the presence of I.C.V. Ang-(1–7) infusion, on the expression of various RAS genes, pro-inflammatory cytokines and iNOS. The data presented in Fig. 5A–D indicate that there are no changes in the expression of Mas, AT1R, ACE2 or iNOS mRNAs within the whole ipsilateral brain hemisphere at 24 h following stroke induction. Likewise, there was no effect of stroke on the levels of mRNAs for the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1α and IL-1β within the whole ipsilateral hemisphere (data not shown), but IL-6 mRNA was significantly increased (Fig. 5E). Intracerebroventricular Ang-(1–7) infusion (1.1 nM; 0.5 μl h−1) for 7 days did not elicit any significant changes in expression of the above genes in the stroked rats (Fig. 5A–E). As it is possible that changes in gene expression are ‘diluted out’ when analysing the whole ipsilateral cerebral hemisphere, in further studies we focused on gene expression in the intracerebral infarct zone. Our qRT-PCR analyses 24 h following ET-1-induced MCAO revealed a significant increase in iNOS mRNA levels in the cerebral cortex of rats that had been pretreated with aCSF (I.C.V. infusion for 7 days), when compared with rats that had undergone sham MCAO (Fig. 5F). This increase in cerebral cortical iNOS mRNA in the rats that underwent ET-1-induced MCAO was significantly attenuated in the animals that were infused I.C.V. with Ang-(1–7) (1.1 nM; 0.5 μl h−1; Fig. 5F). Angiotensin-(1–7) infusion did not alter cerebral cortical iNOS mRNA levels in the sham MCAO rats (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5. Intracerebral gene expression elicited by ET-1-induced MCAO: effects of Ang-(1–7).

A–E, rats were pretreated via I.C.V. infusion with either aCSF (0.5 μl h−1) or Ang-(1–7) (1.1 nM; 0.5 μl h−1) for 7 days prior to ET-1-induced MCAO or sham stroke (injection of 0.9% saline instead of ET-1). Twenty-four hours later, rats were killed, after which brains were removed and processed for qRT-PCR as detailed in the Methods. The bar graphs are means + SEM of Mas, AT1R, ACE2 iNOS, and IL-6 mRNA levels from the whole ipsilateral (right) hemisphere of each treatment group. *P < 0.05 versus corresponding sham treatment (n = 5–6 rats per group). F, rats were pretreated exactly as described for A–E. The bar graphs are means + SEM of iNOS mRNA levels from the ipsilateral (right) cerebral cortex stroke zone of each treatment group. *P < 0.05 versus corresponding sham treatment; †P < 0.05 versus corresponding ET-1/aCSF group; (n = 5–8 rats per group). Note that these data are presented as (ΔΔCt) values, thus a lower value represents an increase in mRNA level.

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that Ang-(1–7) is cerebroprotective during ischaemic stroke. This is supported by our findings that central administration of either exogenous Ang-(1–7) or an ACE2 activator (DIZE) limits the cerebral damage and behavioural deficits elicited by ET-1-induced MCAO, effects that are mediated by the Ang-(1–7) receptor, Mas. Thus, the data presented here provide proof of concept that activation of Mas by Ang-(1–7) can exert a cerebroprotective action during ischaemic stroke, opposite to the effects of Ang II via AT1R. Despite the above findings, the present study raises many important questions.

One of the major issues concerns the locus and mechanism of the cerebroprotective action of Ang-(1–7). Our preliminary immunostaining data (Regenhardt et al. 2010), which indicate that Mas is present on neurons, microglia and (to a lesser extent) endothelial cells in normal brain, would suggest that the beneficial actions of this peptide are localized at one or more of those sites. In addition, qRT-PCR analyses of cerebral cortical tissue from the infarct site of rats that underwent ET-1-induced stroke suggest that the protective action of Ang-(1–7) involves inhibition of iNOS (Fig. 5F). The latter finding is particularly relevant because it is established that induction of iNOS in glia and neurons and subsequent generation of toxic levels of NO are amongst the delayed events that contribute to neuronal death following cerebral ischaemia (Nakashima et al. 1995; Iadecola & Ross, 1997; Parmentier et al. 1999; Moro et al. 2004). Thus, based on our findings, inhibition of iNOS and generation of NO may be one locus of the cerebroprotective action of Ang-(1–7). However, it is also well known that there are other potential protective mechanisms that may be influenced by Ang-(1–7), for example, increases in the ratio of Ang II type 2 receptors (AT2R)/AT1R and of Mas/AT1R expression, and early increases in the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and NO (Feng et al. 2010). Nitric oxide exerts an early protective role after brain ischaemia (Moro et al. 2004). Soon after the ischaemic episode, NO generated by eNOS is cerebroprotective by promoting vasodilatation and improving blood flow in the penumbra region of the stroke (Zhang et al. 1994; Salom et al. 2000). Our data show that Mas receptors are also present in low levels on endothelial cells of cerebral vessels (Regenhardt et al. 2010), and Ang-(1–7) has been shown to increase eNOS activity and NO generation in the brain within 3 h (Zhang et al. 2008). Thus, while it is clear that I.C.V. infusion of Ang-(1–7) at the dose used here does not influence the ET-1-induced vasoconstriction and reduction in CBF (Fig. 1), we are not able to exclude the possibility that Ang-(1–7)-induced activation of eNOS, NO production and subsequent vasodilatation constitutes a part of the cerebroprotective action of this peptide. It is also of note that Mas antagonism alone did not significantly increase the cerebral damage that occurred when compared with a control I.C.V. infusion of aCSF. This may be an indication that endogenous Ang-(1–7) does not play a significant protective role in our stroke model. However, stimulation of Mas with endogenous Ang-(1–7) clearly uncovers pre-existing cerebroprotective pathways. In summary, it is likely that there are multiple mechanisms and cell types involved in mediating the cerebroprotective action of Ang-(1–7), and our continuing studies are aimed at further defining the role of different nitric oxide synthase isoforms in the cerebroprotective action of Ang-(1–7). For example, this will include determining the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are induced in the brain following ischaemia and induce iNOS expression in the cerebral infarct zone (Rothwell & Relton, 1993; Jin et al. 2010). Along these lines, our preliminary results indicate that ET-1-induced stroke results in significant increases in IL-1α and IL-1β mRNAs within the cerebral cortical and striatal infarct zones, and the increases in these pro-inflammatory cytokines are attenuated by I.C.V. Ang-(1–7) infusion (Regenhardt et al. 2010). A further approach will be to evaluate the role of activated microglia, derived from the corpus callosum, which are known to potentiate ischaemic injury by increased expression of iNOS (Lee et al. 2005).

The finding that central administration of DIZE, a recently described activator of ACE2 (Gjymishka et al. 2010), exerted a reduction in cerebral infarct size similar to that obtained following administration of exogenous Ang-(1–7) reinforces the idea that activation of the central ACE2–Ang-(1–7)–Mas axis is beneficial in ischaemic stroke. This is because ACE2 is highly effective at converting Ang II to Ang-(1–7) (Tipnis et al. 2000), and because the observed cerebroprotective action of DIZE was attenuated by inhibition of Mas (Fig. 4). Nonetheless, two issues concerning ACE2 activation by DIZE bear discussion. First, that activation of ACE2 will not only increase Ang-(1–7) levels, but will also reduce tissue Ang II levels (Ferreira et al. 2010). As AT1R antagonism is known to provide cerebroprotection during ET-1-induced MCAO (Mecca et al. 2009), decreased levels of Ang II and a lack of AT1R stimulation could contribute to the beneficial action of DIZE. Analysis of Ang II and Ang-(1–7) levels in the cerebrum before and following DIZE treatment are a part of our future aims, and will help to shed light on the relative contributions of these peptides to the protective action of DIZE. A second issue concerns the finding that after 7 days of I.C.V. treatment with DIZE there was a modest decrease (−17 mmHg) in systolic blood pressure (Fig. 4), and whether this change in blood pressure contributes to the DIZE-mediated cerebroprotection. However, this decrease is well within the autoregulatory range of the cerebrovasculature and so is unlikely to decrease cerebrovascular reserve. Finally, the possibility that DIZE may act by an off-target mechanism, indirectly influencing the ACE2–Ang-(1–7)–Mas axis, cannot be ruled out and will have to wait for a detailed kinetic structural–functional analysis of DIZE–ACE2 interactions.

The present findings support the hypothesis that Ang-(1–7), either generated endogenously following activation of ACE2 or directly applied to the CNS, can elicit Mas-mediated cerebroprotective effects during ischaemic stroke. As such, the data provide the first demonstration that the protective and anti-Ang II/AT1R actions of ACE2 and Ang-(1–7), which are well documented in peripheral systems (Ferreira et al. 2010), extend to the brain and are relevant to ischaemic stroke. A further interesting question that arises from these studies is whether there is any relationship between the protective actions of Ang-(1–7)/Mas and other cerebroprotective mechanisms. For example, there is a large amount of data which indicates that the levels of AT2R are increased in the peri-infarct zone following transient cerebral ischaemia and that activation of these receptors exerts a cerebroprotective action (Iwai et al. 2004; Li et al. 2005). This AT2R action is particularly relevant during AT1R blockade, when it is thought that that unopposed activation by Ang II of the AT2R contributes to the beneficial actions of ARBs during ischaemic stroke (Li et al. 2005). Thus, it will be important to determine whether the beneficial actions of Ang-(1–7) via Mas and of Ang II via AT2R during ischaemic stroke share common intracellular mechanisms.

An intriguing aspect of this work is whether activation of Mas by Ang-(1–7) will ultimately provide a new therapeutic avenue for ischaemic stroke. The present study, where Ang-(1–7) was applied prior to and during stroke, certainly proves the concept that this peptide can exert beneficial actions. It shows that activation of the ACE2–Ang-(1–7)–Mas axis may be a viable preventative strategy for individuals who exhibit the well-known risk factors for stroke. Perhaps activating this axis, in combination with other anti-hypertensive therapies, may decrease morbidity and mortality due to stroke. However, it will be essential to demonstrate that Ang-(1–7) is as effective when administered postischaemic insult in reducing cerebral damage and behavioural deficits.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association Greater Southeast Affiliate (09GRNT2060421), the American Medical Association, and from the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Adam Mecca is a NIH/NINDS, NRSA predoctoral fellow (F30 NS-060335). Robert Regenhardt received predoctoral fellowship support from the University of Florida Multidisciplinary Training Program in Hypertension (T32 HL-083810). Timothy O’Connor and Jason Joseph were supported by University of Florida HHMI Science for Life and University Scholars Program undergraduate research fellowships.

References

- Becker LK, Etelvino GM, Walther T, Santos RA, Campagnole-Santos MJ. Immunofluorescence localization of the receptor Mas in cardiovascular-related areas of the rat brain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1416–H1424. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00141.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederson JB, Pitts LH, Tsuji M, Nishimura MC, Davis RL, Bartkowski H. Rat middle cerebral artery occlusion: evaluation of the model and development of a neurologic examination. Stroke. 1986;17:472–476. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benter IF, Yousif MH, Cojocel C, Al-Maghrebi M, Diz DI. Angiotensin-(1–7) prevents diabetes-induced cardiovascular dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H666–H672. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00372.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Shah HP, Glushakov AV, Mecca AP, Shi P, Sumners C, Seubert CN, Martynyuk AE. Efficacy of 3,5-dibromo-L-phenylalanine in rat models of stroke, seizures and sensorimotor gating deficit. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:2005–2013. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Chaves P, Cerqueira R, Pintalhao M, Leite-Moreira AF. New pathways of the renin-angiotensin system: the role of ACE2 in cardiovascular pathophysiology and therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:485–496. doi: 10.1517/14728221003709784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai WJ, Funk A, Herdegen T, Unger T, Culman J. Blockade of central angiotensin AT1 receptors improves neurological outcome and reduces expression of AP-1 transcription factors after focal brain ischemia in rats. Stroke. 1999;30:2391–2398. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2391. discussion 2398–2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doobay MF, Talman LS, Obr TD, Tian X, Davisson RL, Lazartigues E. Differential expression of neuronal ACE2 in transgenic mice with overexpression of the brain renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R373–R381. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00292.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont AG, Brouwers S. Brain angiotensin peptides regulate sympathetic tone and blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1599–1610. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833af3b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Xia H, Cai Y, Halabi CM, Becker LK, Santos RA, Speth RC, Sigmund CD, Lazartigues E. Brain-selective overexpression of human angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 attenuates neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;106:373–382. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira AJ, Santos RA, Bradford CN, Mecca AP, Sumners C, Katovich MJ, Raizada MK. Therapeutic implications of the vasoprotective axis of the renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular diseases. Hypertension. 2010;55:207–213. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleegal MA, Sumners C. Drinking behavior elicited by central injection of angiotensin II: roles for protein kinase C and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R632–R640. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00151.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JH, Wagner S, Liu KF, Hu XJ. Neurological deficit and extent of neuronal necrosis attributable to middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Statistical validation. Stroke. 1995;26:627–634. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez CL, Kolb B. A comparison of different models of stroke on behaviour and brain morphology. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1950–1962. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobe JL, Mecca AP, Lingis M, Shenoy V, Bolton TA, Machado JM, Speth RC, Raizada MK, Katovich MJ. Prevention of angiotensin II-induced cardiac remodeling by angiotensin-(1–7) Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H736–H742. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00937.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth W, Blume A, Gohlke P, Unger T, Culman J. Chronic pretreatment with candesartan improves recovery from focal cerebral ischaemia in rats. J Hypertens. 2003;21:2175–2182. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200311000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjymishka A, Kulemina LV, Shenoy V, Kayovich MJ, Ostrov DA, Raizada MK. Diminazene aceturate is an ACE2 activator and a novel antihypertensive drug. FASEB J. 2010;24:1032.3. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Prada JA, Ferreira AJ, Katovich MJ, Shenoy V, Qi Y, Santos RA, Castellano RK, Lampkins AJ, Gubala V, Ostrov DA, Raizada MK. Structure-based identification of small-molecule angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activators as novel antihypertensive agents. Hypertension. 2008;51:1312–1317. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.108944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, Ross ME. Molecular pathology of cerebral ischemia: delayed gene expression and strategies for neuroprotection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;835:203–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai M, Liu HW, Chen R, Ide A, Okamoto S, Hata R, Sakanaka M, Shiuchi T, Horiuchi M. Possible inhibition of focal cerebral ischemia by angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation. Circulation. 2004;110:843–848. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138848.58269.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: role of inflammatory cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:779–789. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagiyama T, Glushakov AV, Sumners C, Roose B, Dennis DM, Phillips MI, Ozcan MS, Seubert CN, Martynyuk AE. Neuroprotective action of halogenated derivatives of L-phenylalanine. Stroke. 2004;35:1192–1196. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000125722.10606.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Cho GS, Kim HJ, Lim JH, Oh YK, Nam W, Chung JH, Kim WK. Accelerated cerebral ischemic injury by activated macrophages/microglia after lipopolysaccharide microinjection into rat corpus callosum. Glia. 2005;50:168–181. doi: 10.1002/glia.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Gao Y, Qi Y, Katovich MJ, Jiang N, Braseth LN, Scheuer DA, Shi P, Sumners C. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus neurons decreases blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. FASEB J. 2008;22:3175–3185. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-108662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Culman J, Hortnagl H, Zhao Y, Gerova N, Timm M, Blume A, Zimmermann M, Seidel K, Dirnagl U, Unger T. Angiotensin AT2 receptor protects against cerebral ischemia-induced neuronal injury. FASEB J. 2005;19:617–619. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2960fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecca AP, O’Connor TE, Katovich MJ, Sumners C. Candesartan pretreatment is cerebroprotective in a rat model of endothelin-1-induced middle cerebral artery occlusion. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:937–946. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.047936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger R, Bader M, Ludwig T, Berberich C, Bunnemann B, Ganten D. Expression of the mouse and rat mas proto-oncogene in the brain and peripheral tissues. FEBS Lett. 1995;357:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro MA, Cardenas A, Hurtado O, Leza JC, Lizasoain I. Role of nitric oxide after brain ischaemia. Cell Calcium. 2004;36:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima MN, Yamashita K, Kataoka Y, Yamashita YS, Niwa M. Time course of nitric oxide synthase activity in neuronal, glial, and endothelial cells of rat striatum following focal cerebral ischemia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1995;15:341–349. doi: 10.1007/BF02089944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y, Ito T, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin II AT1 blockade normalizes cerebrovascular autoregulation and reduces cerebral ischemia in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke. 2000;31:2478–2486. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier S, Bohme GA, Lerouet D, Damour D, Stutzmann JM, Margaill I, Plotkine M. Selective inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase prevents ischaemic brain injury. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:546–552. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peregrine AS, Mamman M. Pharmacology of diminazene: a review. Acta Trop. 1993;54:185–203. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(93)90092-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regenhardt RW, Mecca AP, Desland F, Ritucci P, Sumners C. Program No. 658.7. 2010 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. San Diego, CA: Society for Neuroscience; 2010. Angiotensin reduces cerebral cortical iNOS expression in ischemic stroke: possible mechanism for cerebroprotection. 2010. Online. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell NJ, Relton JK. Involvement of interleukin-1 and lipocortin-1 in ischaemic brain damage. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1993;5:178–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra JM. Brain angiotensin II: new developments, unanswered questions and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:485–512. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-4011-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salom JB, Orti M, Centeno JM, Torregrosa G, Alborch E. Reduction of infarct size by the NO donors sodium nitroprusside and spermine/NO after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2000;865:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos RA, Ferreira AJ, Simoes E, Silva AC. Recent advances in the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2–angiotensin(1–7)–Mas axis. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:519–527. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.042002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos RA, Simoes e Silva AC, Maric C, Silva DM, Machado RP, de Buhr I, Heringer-Walther S, Pinheiro SV, Lopes MT, Bader M, Mendes EP, Lemos VS, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Schultheiss HP, Speth R, Walther T. Angiotensin-(1–7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8258–8263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432869100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey J, Ritchie IM, Kelly PA. Perivascular microapplication of endothelin-1: a new model of focal cerebral ischaemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:865–871. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thöne-Reineke C, Steckelings UM, Unger T. Angiotensin receptor blockers and cerebral protection in stroke. J Hypertens Suppl. 2006;24:S115–S121. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000220416.07235.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, Karran E, Christie G, Turner AJ. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. cCloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33238–33243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Sriramula S, Lazartigues E. ACE2/ANG-(1–7)/Mas pathway in the brain: the axis of good. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R804–R817. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00222.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, White JG, Iadecola C. Nitric oxide donors increase blood flow and reduce brain damage in focal ischemia: evidence that nitric oxide is beneficial in the early stages of cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994;14:217–226. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lu J, Shi J, Lin X, Dong J, Zhang S, Liu Y, Tong Q. Central administration of angiotensin-(1–7) stimulates nitric oxide release and upregulates the endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression following focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats. Neuropeptides. 2008;42:593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]