Abstract

GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio B syndrome, both arising from beta-galactosidase (GLB1) deficiency, are very rare lysosomal storage diseases with an incidence of about 1:100,000– 1:200,000 live births worldwide. Here we report the beta-galactosidase gene (GLB1) mutation analysis of 21 unrelated GM1 gangliosidosis patients, and of 4 Morquio B patients, of whom two are brothers. Clinical features of the patients were collected and compared with those in literature. In silico analyses were performed by standard alignments tools and by an improved version of GLB1 three-dimensional models. The analysed cohort includes remarkable cases. One patient with GM1 gangliosidosis had a triple X syndrome. One patient with juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis was homozygous for a mutation previously identified in Morquio type B. A patient with infantile GM1 gangliosidosis carried a complex GLB1 allele harbouring two genetic variants leading to p.R68W and p.R109W amino acid changes, in trans with the known p.R148C mutation.

Molecular analysis showed 27 mutations, 9 of which are new: 5 missense, 3 microdeletions and a nonsense mutation. We also identified four new genetic variants with a predicted polymorphic nature that was further investigated by in silico analyses.

Three-dimensional structural analysis of GLB1 homology models including the new missense mutations and the p.R68W and p.R109W amino acid changes, showed that all the amino acids replacements affected the resulting protein structures in different ways, from changes in polarity to folding alterations. Genetic and clinical associations led us to undertake a critical review of the classifications of late-onset GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio B disease.

Keywords: beta-galactosidase, GM1- gangliosidosis, Morquio B, mutation update, homology modelling

INTRODUCTION

GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio B are autosomal recessive storage disorders caused by the deficiency of β-galactosidase (GLB1), a lysosomal hydrolase that may be defective with respect to keratan sulfate (in Morquio B disease) or to gangliosides, lactosylceramide, asialofetuin, oligosaccharides carrying terminal β-linked galactose and keratan sulfate (in GM1 gangliosidosis) [1, 2].

GM1 gangliosidosis is a neurodegenerative condition for which three main clinical forms have been identified: type I (infantile), type II (late infantile/juvenile), and type III (adult) [1]. The severe infantile phenotype (type I) is characterised by psychomotor regression by the age of 6 months, visceromegaly, cherry-red spot, and facial and skeletal abnormalities [1]. The type II form usually starts between 7 months and 3 years of age with slowly progressive neurological signs including early locomotor problems, strabismus, muscle weakness, seizures, lethargy, and terminal bronchopneumonia [1]. Dysmorphisms and skeletal changes are less severe than seen in Type I. The adult form (type III), the mildest phenotype of the disease, with onset between 3 and 30 years, is characterised by cerebellar dysfunction, dystonia, slurred speech, short stature and mild vertebral deformities [1]. The estimated incidence of GM1 gangliosidosis is 1:100,000–200,000 live births [3].

Morquio B disease is a mucopolysaccharidosis (also called MPS IVB) characterised by typical and massive skeletal changes, corneal clouding and impaired cardiac function. A primary central nervous system involvement is not proven [1]. The estimated incidence of Morquio B covers a wide range, from 1 case per 75,000 births in Northern Ireland [4], to 1 case per 640,000 in Western Australia [5].

A problematic partition between Morquio B and juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis phenotypes has been discussed [2]. An intermediate phenotype between GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio B disease was also recently proposed in a patient homozygous for the p.R333H mutation [6]. Likewise, a patient with an intermediate phenotype between infantile and juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis has been reported and associated with a complex allele carrying the common p.R201H amino acid substitution in cis with the p.L436F polymorphism [7].

At present only symptomatic treatments are available for GM1 gangliosidosis or Morquio B diseases. Substrate Reduction Therapy mediated by N-butyldeoxynojirimycin (NB-DNJ, Miglustat) has been used with encouraging results for the treatment of patients with mild to moderate type 1 Gaucher disease, Niemann-Pick disease type C and chronic GM2 gangliosidosis type Sandhoff [8–11]. Interesting results have also been reported in a mouse model of GM1 gangliosidosis [12].

The GLB1 protein is encoded by the GLB1 gene (E.C.3.2.1.23; MIM 230500), mapping on the 3p21.33 chromosome. It gives rise to two alternately spliced mRNAs: a transcript of 2.5 kb, encoding the lysosomal enzyme and a transcript of 2.0 kb encoding the Elastin Binding Protein (EBP), which is located in the endosomal compartment [13, 14]. It has been demonstrated that a depletion of EBP in arterial smooth muscle, fibroblasts and chondroblasts interferes with elastic-fiber assembly [15, 16].

To date more than 130 genetic lesions have been described [3, 17]. The tertiary structure of human GLB1 has not been resolved, although the Glu268 and the Asp332 residues, conserved between species, appear to be part of the catalytic sites [18–20]. A previous homology model of human GLB1 was derived from the structure of the Bacteroides Thetaiotaomicron GLB1 protein [21].

Here we report the molecular analysis of 21 GM1 gangliosidosis patients and 4 Morquio B patients, as well as the in silico and structural characterisation of the new amino acid variants identified, including mutations and polymorphisms. Our purpose for undertaking this study was to clarify the role of the mutated alleles in determining patients’ phenotypes and improve the molecular diagnostic yield in differentiating GM1 forms and/or Morquio B disease. On the basis of the clinical evidence reported herein and of a literature review, we discuss the appropriateness of the classification of GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio B forms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

GM1 gangliosidosis patients

The main clinical features are summarised in Table 1- part I and II (GM1 gangliosidosis), and in Table 2 (Morquio B).

Table 1.

Main clinical features of GM1 gangliosidosis patients here reported, part I

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic Origin | Caucasian | Italian | n.r | Caucasian | Caucasian | Indian | Romanian | Turkish | Lybian | Caucasian |

| Phenotype | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Onset | 4m | 4m | neonatal | fetal | − | fetal | 4m | neonatal | 5m | 2m |

| Presentation | edema | hypotonia | − | hydrops fetalis | − | microcephaly, cardiomegaly | psychomotor delay, hypotonia | psychomotor delay | pneumonia, respiratory insufficiency | psychomotor delay, hypotonia |

| Age at diagnosis | 10m | 7m | neonatal | 2m | − | 19m | 7m | 7m | 6m | 9m |

| Psychomotor delay | mild | no active posturing | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Nervous and muscle systems | hypotonia, gelastic seizures | − | − | hypotonia, spasticity | − | hypotonia, seizures, myoclonic jerks | hypotonia | hypotonia | − | tetraparesis, drug-resistant epilepsy, dysphagia |

| Coarse facies | mild | + | − | + | − | no | + | − | no | + |

| Eyes * | − | no | − | c.r.s | − | nystagmus | c.r.s | c.r.s | c.r.s | c.r.s |

| Spleen/ liver megaly | mild | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | mild | − |

| Cardio myopathy | no | no | − | + | − | + | no | − | RBBB | no |

| Respiratory involvement | + | no | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | + |

| Brain MRI | dysmielinisation | − | − | − | − | t.c.c (13m) | supra and sub tentorial w.m hyperintensity | − | − | basal ganglia, thalami and w.m hyperintensity |

| GLB1 (nmol/mg/h) | 2,0 F(n.v……….) | absent | absent | absent | − | absent | absent | 2,0 S (n.v. 50–1025) | absent | 0,6 L (n.v. 90–160) |

| Other | gibbous, scoliosis, bone demineralization, PEG (14m), macrocephaly | − | − | + | − | absence of type 2A, atrophy of type 2B and 2C fibres | umbilical hernia, vertebral hypoplasia | − | − | − |

| Exitus | Alive (16m) | 22 m | 2m | 26m | − | 19m | 20m | Alive (7m) | − | 17m |

List of abbreviations: I= infantile; J= juvenile; A= adult; + = presence of the symptom; − = not reported data; no = normal; y= year; d=days; m=months. F= on fibroblasts; L= on leukocytes; S= on serum. PFO= patent foramen ovale; RBBB= right bundle branch block; PEG= percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; w.m= white matter; t.c.c= thin corpus callosum.

c.r.s =cherry red spot; v.l. = visual loss; o.a.= optic atrophy.

Table 2.

Main clinical features of GM1 gangliosidosis patients here reported, part II

| Patient | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic Origin | Indian | Caucasian | Caucasian | Sri Lanka | Caucasian | Caucasian | Caucasian | Italian | Italian | Caucasian | Caucasian |

| Phenotype | I | I | I | I | I/J | J | J | J | J | A | A |

| SEX | |||||||||||

| Onset | 3m | 1m | neonatal | 2m | 1y | 5y | 1y | − | 4y | 2y | 4y |

| Presentation | PFO | hypotonia, respiratory insufficiency, PFO | hypotonia, deafness, psychomotor delay, hydrocele | psychomotor delay, hypotonia | psychomotor delay | speech impairment | psychomotor delay, hypotonia | − | speech impairment | choreic dystonic and atetoid movements, dysarthria | dysarthria, tremors, ataxia |

| Age at diagnosis | 14m | 9m | − | 14m | 14m | 10y | 3y | − | 11y | 11y | 9y |

| Psychomotor delay | + | + | + | + | + | mild | + | − | + | no | borderline IQ |

| Nervous and muscle systems | hypotonia, myoclonic seizures | hypotonia | tetraparesis | tetraparesis, drug-resistant epilepsy, dysphagia, dystonia | seizures | dysarthria | dysarthria, dystonia | − | Severe dysarthria, dystonia Perkinsonism | spastic tetraparesis, dystonia | dystonia, stiffness |

| Coarse facies | + | no | no | + | − | + | no | − | + | no | no |

| Eyes * | c.r.s, o.a | v.l | no | c.r.s | − | − | no | − | Corneal dystrophy | no | no |

| Spleen/ liver megaly | + | + | + | + | − | − | no | − | − | no | no |

| Cardio myopathy | no | − | + | +, aortic valve insufficiency | − | no | no | − | − | no | no |

| Respiratory involvement | + | + | + | + | + | − | no | − | − | no | no |

| Brain MRI | altered signal intensity of putamen | supra and sub tentorial w.m hyperintensity, t.c.c | altered signal of white matter, hydrocephalus | − | w.m alterations | t.c.c, mild cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, posterior dysmielinisation | brain atrophy | − | Cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, basal ganglia altered signal, posterior dysmielinisation | basal ganglia altered signal | − |

| GLB1 (nmol/mg/h) | absent | absent | 2,5 (n.v………) | absent | 15 F (n.v. 400–1100) | 5,8 L (v.n. 84–292) | 63 F (n.v. 117–408) | − | 4.4 (v.n. 84–292) | 6,2 L (n.v. 90–250); 138 F (n.v. 400–1100) | 5,8 L (n.v. 90–250); 56 F (n.v. 400–1100) |

| Other | − | macrocephaly | − | PEG (10m), umbilical hernia, microcephaly | dysphagia | − | flattened vertebral bodies with hook shaped deformities | − | flattened vertebral bodies femoral head deformity | − | − |

| Exitus | 20m | alive (13m) | − | 2y | alive (3y½) | alive (11y) | alive (22y½) | − | alive (15y) | alive (15y) | alive (10y) |

List of abbreviations: I= infantile; J= juvenile; A= adult; + = presence of the symptom; − = not reported data; no = normal; y= year; d=days; m=months. F= on fibroblasts; L= on leukocytes; S= on serum. PFO= patent foramen ovale; RBBB= right bundle branch block; PEG= percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; w.m= white matter; t.c.c= thin corpus callosum.

c.r.s =cherry red spot; v.l. = visual loss; o.a.= optic atrophy.

The GM1 gangliosidosis patients here reported are affected by infantile or juvenile forms. Clinical assessment of this cohort uncovers three remarkable cases who are described in detail below.

Patient 1, (see Table 1- part I)

This patient is the second child of unrelated parents; the brother is healthy but the patient’s mother showed a history of multiple miscarriages (four foetuses in the first trimester and two during the second trimester of pregnancy). Kariotyping on parents and on one of the miscarried foetuses resulted normal. The patient’s father is of Irish/ Italian descent and the maternal branch is Irish/ Scandinavian.

The patient presented at 4 months with edema in the limbs and increased alkaline phosphatase, referred as the result of a clavicular fracture at birth. No cardiac dysfunction or structural abnormalities as cardiomyopathy or valve defects were found at this period and in the further examinations. X-ray showed some demineralization of the bone and early rachitic changes. Psychomotor and relational development and feeding skills were referred as normal until 1year of age, although mild coarseness of the face and slight hepatosplenomegaly were observed. At 1 year and four months the main clinical findings included moderately severe hearing loss, bilateral inguinal hernia, marked macrocephaly and plagiocephaly, axial hypotonia, and suspected gelastic seizures due to recurrent laughing spells. Gastrostomy tube was introduced due to gastroesophageal reflux, on one occasion complicated by pneumonia. Bone MRI showed gibbous deformity and scoliosis, and brain MRI revealed diffuse dysmyelination. The patient was treated briefly with Miglustat. However due to the severe progressive neurological involvement as well as diarrhoea and weight loss, the treatment was discontinued.

Patient 15 (see Table 1- part II)

The patient is a 3 years 6 months old female who presented with psychomotor regression at 1 year of age. At 16 months she exhibited limb hypotonia and mild psychomotor delay. The biochemical GLB1 enzyme activity measured in cultured fibroblasts was 15nmol/mg/h (n.v. 400–1100), thus resulting in about 2% of control GLB1 activity. She also had a 47, XXX karyotype, and brain MRI revealed aspecific white matter alterations (particularly periventricular).

Due to the age of onset of clinical manifestation the patient was diagnosed with late-infantile/juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis. However, the course of the disease was relatively rapid according to the detection of very low residual GLB1 enzyme activity (about 2% of control values) with psychomotor regression and loss of motor abilities. Currently she also presents severe dysphagia, quadriparesis, frequent respiratory infections and focal seizures.

Patient 20 (see Table 1- part II)

The patient is the second- born female of consanguineous Romanian parents. She had a normal psychomotor development until the age of 2 years when she presented with an episode of diarrhoea and coma followed by motor regression. Six months later she recovered motor abilities and was clinically stable for several years but at age 12 years dyskinetic athetoid movements appeared. Physical examination showed grimaces, dystonic movements in the extremities, dysarthria and ataxia. Mild facial dysmorphism, short-trunk dwarfism, and sternal protrusion were also present. GLB1 measured on leukocytes was 5,5 nM/mg/h (n.v. 90–250) and she was given the diagnosis of juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis. Since the age of 12 years and 6 months, after the Review Board approval, she started treatment with Miglustat with a dosage of 100mg three times a day. After few weeks, due to persistent diarrhoea, the dosage was changed to 100mg two times a day. After 11 months, on her parents’ initiative, the treatment was discontinued for 3 months. Then a maintenance treatment with 100 mg three times a day was reintroduced and it is well tolerated. At present, the patient is 14 years and 6 months old and, despite treatment, clinical worsening has ensued with anarthria, spasticity and loss of autonomous walking.

Genomic DNA analyses and informed consents

Genomic DNA was obtained from patients’ lymphocytes and/or fibroblasts using a commercial DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Oligonucleotides and PCR amplifying conditions were described previously [7, 22]. Sequencing reactions were performed using the ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, U.S.A.) as recommended by the manufacturer. The nomenclature of the new GLB1 gene genetic lesions is as designed previously [23]. The GLB1 mutations were confirmed in patients' and their relatives’ DNA. Informed consent for genetic tests was obtained for all analysed patients included in the study.

Screening of new mutations and in silico analyses

The GLB1 gene of 60 normal control DNA samples was analysed by sequencing analysis of the fragments containing the new missense mutations identified. The PCR fragments were amplified by the genomic primers reported earlier [7, 22]. In addition, alignments of GLB1 related proteins was performed by ClustalW multiple sequence alignment (http://align.genome.jp/) and the single amino acid substitutions were also analysed by PolyPhen tool (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/).

Mapping mutations onto structure of GLB-1 homology model

The structural effect of novel missense mutations on resulting GLB1 enzymes was predicted by modelling the mutations onto the three-dimensional structure of GLB1 based upon two crystal structures, one from Penicillium and one from Bacteroides (PDB codes 1XC6 and 3D3A respectively). Amino acid substitutions corresponding to mutant proteins were introduced into the predicted wild type structure in the molecular graphics program O. Amino acid side chain rotamers for the substitutions were chosen to minimise steric clashes. The resulting three dimensional model of the mutant proteins were energy minimised in the program CNS. Molecular figures were prepared with the program Molscript (http://www.avatar.se/molscript/doc/index.html).

RESULTS

Phenotype- genotype correlations

The study includes 21 GM1 gangliosidosis patients of whom 14 presented with the infantile form of the disease and 6 patients can be classified as juvenile (Tables 1 and 2). Due to her ambivalent manifestations, Patient 15 was assigned as suffering from an infantile/ juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis phenotype (Table 1- part II). In addition, 4 Morquio B patients are described (Table 2). The lysosomal neuraminidase (NEU1) enzyme activity, assayed in leukocytes, was within the normal range in all patients.

Psychomotor delay and hypotonia are the main symptoms presented at the onset of the infantile and juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis forms. Dysostosis multiplex and white matter alterations were also detected in most patients. GM1 gangliosidosis infantile patients also frequently showed macrocephaly, but microcephaly can also be present at birth (see Patient 6, Table 1- part I). The clinical pictures of the 4 Morquio type B patients here reported, summarised in Table 2, showed the classic phenotypes of the disease. It is worth to point out that, in Patient 25, the progressive outcome of severe aortic valve insufficiency (heavily calcified valve with reduced orifice and systolic turbulent flow) resulted in valve replacement (Table 2). Before surgery he also presented mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation. Pulmonary valve was normal.

The clinical assessments of three relevant cases (Patient 1, 15 and 20, Table 1- part I and II) are given in more detail (material and method section) due to the complex correlation between their phenotypes and molecular analyses.

Remarkably, Patient 1 presented with mild neurological involvement and no feeding problems until 1 year, that is atypical for an infantile GM1 gangliosidosis patient. Patient 15 and 20 showed late onset GM1 gangliosidosis manifestations (the onset of symptoms and the relatively old age of Patient 15 at present, and the neurological involvement of Patient 20) coupled with GLB1 mutations previously correlated to the infantile GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio B phenotypes, respectively [24, 25].

Two prenatal diagnoses were performed based on the biochemical and molecular characterisation of Patient 5 and her parents. The foetuses were both not affected, but the first one was miscarried after the prenatal sampling.

Molecular characterisation and in silico analyses

The patients’ GLB1 gene coding regions and the correspondent exon/intron boundaries were amplified and directly sequenced on both strands. The mutations identified were confirmed in the parents’ genomic DNA. The p.K578R mutation, identified in Patient 15, was previously associated with the infantile phenotype [24]. In Patient 20, the p.G438E mutation, previously described in Morquio B patients and type III GM1 gangliosidosis, both at a homozygous level [25, 26], was found. In Patient 1, the new complex allele pR68W/p.R109W, in combination with the known c.442C>T (p.R148C) [27] was found (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Main clinical features of Morquio B patients here reported

| Patient | 22 R.T. | 23 M.T. | 24 R. | 25 E.S. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38 | 42 | 24 | 36 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 32 | 36 | 13yrs and 9 m | 10 |

| SEX | male | female | male | male |

| GLB1 (nmol/17hour/mg protein) | 14.4 (n.v. 28,6–748) | |||

| Parental Consanguinity | yes (sister of 23) | yes (brother of 22) | no | no |

| Height (cm) at present | 151 | 140 | 156,5 | |

| Weight (Kg) at present | 56 | 47 | 53 | 45 |

| Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia | Yes | Yes | Yes | yes |

| Chest Deformity | Yes | Yes | Yes | yes |

| Hearing loss | No | No | No | |

| Corneal Clouding | very mild | very mild | + | |

| Coxa Valga | very mild | Yes | No (right hip replacement april 2009) bilateral hip dysplasia | |

| Odontoid Hypoplasia | No | No | No | |

| Hepato- splenomegaly | No | No | No | |

| Cardiac Involvement (Left ventricular hypertrophy/ valvar disease) | mild aortic reflux | mild aortic reflux | minimal aortic insufficiency | aortic valve insufficiency, mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation |

| Urinary GAGs | 46.10 mg GAG/g CREATININA (n.v 3–40) Ks: 2.5 mg/cret (n.v 0-0-17) | |||

A summary of the 27 mutations identified (18 known and 9 new) in the GLB1 enzyme of the 25 patients here reported is shown in Table 3. New genetic lesions include five amino acid substitutions, p.I51N, p.L69P, p.R148H, p.W161G, and p.S191N, three small deletions c.424_427 del4, c.1069_70_71delT, c.1303delC and one nonsense mutation, p.W92X.

A possible benign polymorphic nature of each new nucleotide variants above mentioned was excluded by sequencing analysis of the GLB1 exons containing the aforementioned mutated nucleotides in 120 control alleles. The presence of these amino acid substitutions in less than 1% of normal alleles screened, suggested that they are not benign substitutions. In addition, sequence alignments of GLB1 related proteins (glycosyl hydrolase family 35), indicated that the p.I51, p.L69, and p.W161 amino acids are highly conserved across species, the p.R148 is quite conserved, while the p.S191 amino acid is dispersed among species (Fig. 1). Polyphen analysis confirmed the data of Clustal W alignments (data not shown). However, a careful observation of the p.S191 Clustal W output showed a total conservation of this amino acid in Mammalian (Mouse), Fungi (Aspergillus), Proteobacteria (the Gram – Xanthomonas manihotis) and in the Gram+ Bacillus circulans, while the complete loss of homology resulted from alignments with the Gram+ Actinobacterium (Arthrobacter) and with Plants (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. GLB1 sequence alignments between species.

Family 35 glycosyl hydrolases and related proteins were aligned in the regions surrounding the new amino acid changes (p.I51N, p.L69P, p.R109W, p.R148H, p.W161G, and p.S191N) identified in GM1 gangliosidosis patients. Both aligned amino acids are indicated by squares. * Total sequence homology; : Very high homology;. High homology. A. p.I51 and p.L69 amino acids; B. p.R109 amino acid; C. p.R148 and p.W161 amino acids; D. p.S191 amino acid.

In addition we identified four new nucleotide variants [c.325C>T (p.R109W), c.1824G>C, c.858C>T, and IVS7 +10g>t] with a predicted polymorphic nature due to their presence in combination with two known mutations or with here confirmed to be pathogenetic alterations detected in the correspondent patients’ GLB1 genes. The p.R109W amino acid substitution, the only one involved in a missense change, was not found in 180 control alleles. In contrast, in silico analyses (both Polyphen and Clustal W alignments) predicted a polymorphic nature with confident assignment (see Fig. 1). In addition Patients 5 and 17 (Table 1-part I and II) also presented this amino acid substitution, and from genetic analysis on their families the p.R109W was proven to be in association (in cis) with the known p.R351X stop mutation in both cases.

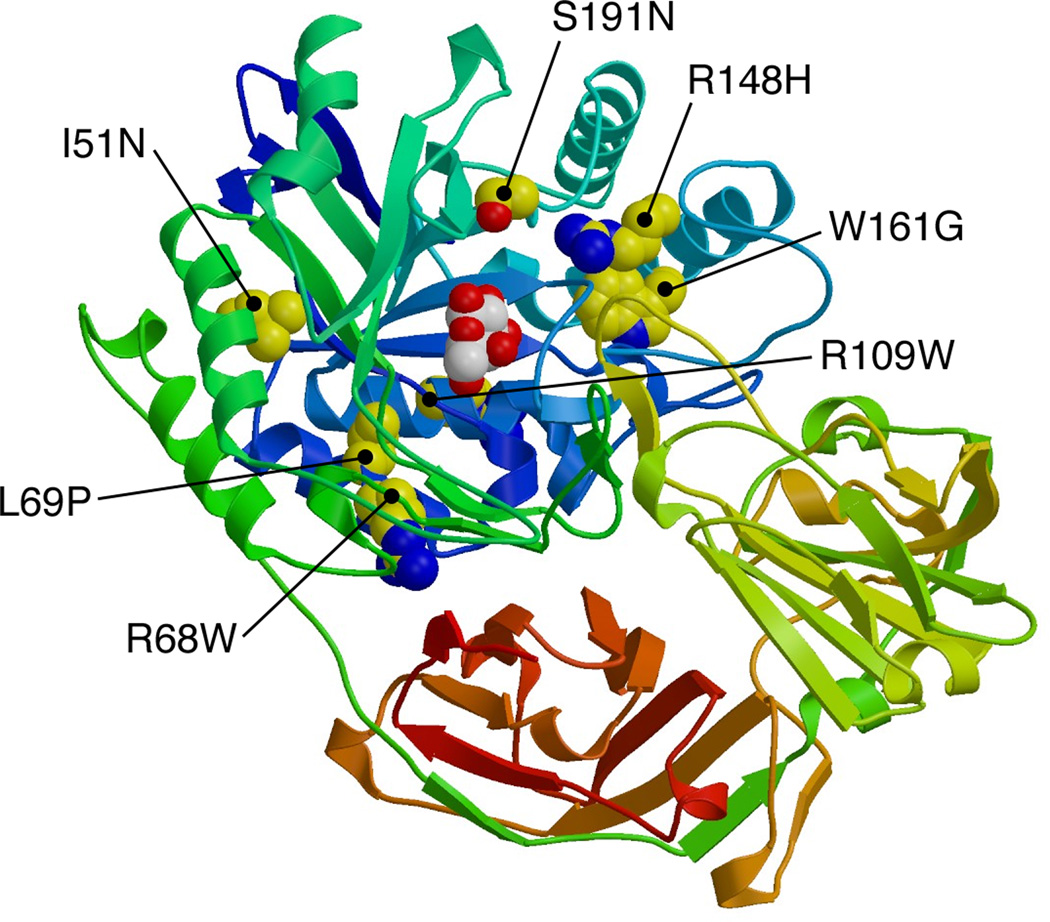

Three-dimensional analyses

To further explain the effects of the new amino acid changes, we looked at the protein structure on the molecular predicted graphic of human GLB1 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Structural model of representatitive human GLB1 three- dimensional protein.

Homology model of human GLB1 based upon two crystal structures, one from Penicillium and one from Bacteriodes, is presented. The structure was plotted and the amino acid substitutions p.I51N, p.R68W, p.L69P, p.R109W, p.R148H, p.W161G, and p.S191N were highlighted in the molecular graphic. The selected amino acids are in yellow and the galactose ligand in white, with the protein painted from NH2- starting to COOH- terminal with blue to red colours.

As shown in Table 4, each mutation is predicted to influence the protein structure in different ways, from changes in polarity to packing defects and changes in aggregation proneness.

Table 4.

Molecular analyses of the 25 patients here reported

| Patient | Phenotype | Nucleotide change |

Amino acid substitution |

Other genetic alterations |

Mutation Ref. | Polymorphism Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Infantile GM1 | c.442C>T/c.202C>T | p.R148C/p.R68W | c.325C>T (R109W) (+/−) | Caciotti et al. 2007/Caciotti et al. 2003 | This work |

| 2 | Infantile GM1 | c.1736G>A/c.1736G>A | p.G579D/p.G579D | Morrone et al.2000 | ||

| 3 | Infantile GM1 | c.1736G>A/c.1736G>A | p.G579D/p.G579D | Morrone et al.2000 | ||

| 4 | Infantile GM1 | c.443G>A/c.1480 -2a>g | p.R148H/frameshift | This work/ Morrone et al.2000 | ||

| 5 | Infantile GM1 | c.1051C>T/c.1051C>T | p.R351X/p.R351X | c.325C>T (R109W)/(+/+) | Hinek et al. 2000 | This work |

| 6 | Infantile GM1 | c.1069del3/c.1309_1310 delA | frameshifts | This work/Caciotti hum mut 2005 | ||

| 7 | Infantile GM1 | c.481T>G/c.841C>T | p.W161G/pH281Y | c.29C>T (p.L10P) (+/−), c.858C>T (p.T286T) (+/−) | This work/ Paschke et al. 2001 | Silva et al. 1999, This work |

| 8 | Infantile GM1 | c.1040A>G/c.1040A>G | p.Y347C/p.Y347C | c.792+10g>t (+/−) | Santamaria et al. 2006 | This work |

| 9 | Infantile GM1 | c.994G>A/c.994G>A p.D332N/p.D332N | p.D332N/p.D332N | Zhang et al. 2000 | ||

| 10 | Infantile GM1 | c.1321A>G/c.1445G>A | p. D441N/p.R482H | Santamaria et al. 2006/ Oshima et al. 1991 | ||

| 11 | Infantile GM1 | c.275G>A/c.75+2dupT | p.W92X /frame shift | Chakraborty et al. 1994 | ||

| 12 | Infantile GM1 | c.424_428 del4/c.841C>T | frame shift/(p.H281Y) | c.29C>T (p.L10P) (+/−), c.34C>T (p.L12L) (+/−), c.858C>T (p.T286T) (+/−) | This work/ Paschke et al. 2001 | Silva et al. 1999, This work |

| 13 | Infantile GM1 | c.206T>C /c.1728G>A | p.L69P/W576X | c.1233+8T>C | This work/ Santamaria et al. 2007 | Caciotti et al. 2007 |

| 14 | Infantile GM1 | c.1303 del c | frameshift | This work | ||

| 15 | Infantile/Juvenile GM1 | c.1733 A>G/c.1733 A>G | p.K578R/p.K578R | Boustany et al. 1993 | ||

| 16 | Juvenile GM1 | c.152T>A/c.602G>A/ | p.I51N/p. R201H | This work/ Kaye et al. 1997 | ||

| 17 | Juvenile GM1 | c.572 G>A/c.1051 C>T | p.S191N/p.R351X | c.325C>T-(R109W) (+/−) | This work/ Hinek et al. 2000 | This work |

| 18 | Juvenile GM1 | c.602G>A/c.1728G>A | p.R201H/p.W576X | Kaye et al. 1997/Santamaria et al. 2007 | ||

| 19 | Juvenile GM1 | c.152T>A/c.602G>A/ | p.I51N/p.R201H | This work /Kaye et al 1997 | ||

| 20 | Adult GM1 | c.1313G>A/c.1313G>A | p.G438E/p.G438E | c.29C>T (p.L10P) | Bagshaw et al. 2002 | Silva et al. 1999 |

| 21 | Adult GM1 | c.275G>A/c.1325G>A | p.W92X/R442Q | c.1233+8T>C (+/−), c.1594A>G (p.S532G) (+/−) | This work / Caciotti et al. Am J Pathol, 2005 | Caciotti et al. 2007, Zhang et al. 2000 |

| 22 | MorquioB | c.851–852TG>CT/c.851–852TG>CT | p.W273L/p.W273L | Oshima et al. 1991 | ||

| 23 | MorquioB | c.851–852TG>CT/c.851–852TG>CT | p.W273L/p.W273L | Oshima et al.1991 | ||

| 24 | MorquioB | c.851–852TG>CT/c.1480 -2a>g | p.W273L/frame shift | Oshima et al.1991/ Morrone et al. 2000 | ||

| 25 | MorquioB | c.1321A>G/c.851–852TG>CT | p.D441N/p.W273L | Santamaria et al. 2007/ Oshima et al. 1991 |

Abbreviation. (+/−)= heterozygous level; (+/+)= homozygous level. Ref.= References

DISCUSSION

The molecular bases of the diseases can be related to (i) the kinetic and processing of mutated GLB1, (ii) to the role of both GLB1 gene products, GLB1 and EBP, and (iii) to the interactions of these proteins within their complexes inside lysosomes and on the cell surface, respectively [19, 20].

Of the 27 different genetic lesions identified in our patients’ cohort nine were new, confirming the high genetic heterogeneity of GLB1 gene.

The common mutation p.R201H, was identified in 3 Juvenile patients, and the p.W273L in at least one allele of Morquio B patients (see Table 3). The p.G579D was found in 2 unrelated patients and previously reported in Italian infantile patients [22, 27]. Otherwise, the five new missense genetic lesions [c.152T>A (p.I51N), c.206T>C (p.L69P), c.443G>A (p.R148H), c.481T>G (p.W161G), c.572 G>A (p.S191N)], and the three microdeletions (c.424_428 del4, c.1069delT, c.1303delC) are private mutations.

The p.I51N was detected in two juvenile patients in combination with the p. R201H. These patients, although consanguinity was not referred, are both from a small village in Southern Italy.

The new nonsense mutation p.W92X was identified in two unrelated patients with different phenotype (see Table 3).

The discussion of the cases at a clinical and genetic level underlines that univocal genotype phenotype correlations are difficult to be drawn. In particular, Patient 21 is a compound heterozygous for the p.W92X and p.R442Q mutations with about 5% of residual GLB1 activity. The p.R442Q change was previously detected in a compound heterozygous Italian patient with an adult phenotype [28]. Expression studies demonstrated that the p.R442Q showed residual GLB1 enzyme activity in contrast with a total absence of GLB1 activity in the in vitro expression system of the p.T329A mutation. In this adult patient no additional genetic variants predicted to have a modulating effects were detected [28, personal data]. Patient 21 (10 years old) recently showed a severe CNS neurological worsening, thus being classified as affected by the juvenile form. Her clinical outcome is quite different from the reported adult patient [28], who shares with her the p.R442Q mutant allele but who presents a very mild CNS involvement at the age of 27 years (last referred examination before starting therapy with Miglustat). A known polymorphic variant (p.S532G) [29], that leads to a complex allele carrying the p.R442Q and p.S532G variants, was identified in the GLB1 gene of Patient 21. An influence of this combination in determining residual enzyme activity and thus phenotype, might be hypothesised. We would like to point out the importance of reporting all polymorphisms, since they could play a role in determining phenotypes, especially when considering otherwise ambivalent genotype/phenotype correlations.

Patient 1 showed a noteworthy genetic assessment, consisting of a complex GLB1 allele carrying two genetic variants leading to p.R68W and p.R109W amino acid changes, in combination with the known c.442C>T (p.R148C) mutation on the other allele. The p.R68W and p.R148C mutations were previously shown to result in an absence of GLB1 enzyme activity [7, 27], thus correlating with the infantile phenotype. However, this patient was not referred to show psychomotor delay until 1 year of age. Genotype/phenotype correlations were investigated further by Polyphen and ClustalW tools and by structure analysis. All in silico analyses indicated that the p.R68W is a severe mutation located in an extremely conserved GLB1 region, affecting the packing of the core of the molecule. The amino acid change p.R109W, that is positioned in cis with the p.R68W mutation, resulted polymorphic from both performed alignments (Clustal W output is shown in Fig. 1). However, mutation screening by sequencing analyses failed to find the correspondent genetic lesion in about 90 control DNAs (180 alleles).

Mutation of a surface exposed residue from arginine to tryptophan would result in much more hydrophobic surface on the molecule, which may lead to aggregation of the protein. Protein interfaces are enriched in aromatic residues like tryptophan, 21% vs. 8% in non-interface surface residues [30]. The most common pairing of residues in protein–protein interfaces involves interactions between hydrophobic residues, especially the bulky aromatic residues [31]. The amino acids Trp, Met, and Phe are important for protein–protein interactions [32]. Thus, the introduction of a large aromatic residue like a tryptophan makes the protein more likely to interact with other proteins and make it more likely to aggregate.

To assess the possibility that this amino acid change (p.R109W) has a modulating role, the maturation of the GLB1 precursor may be considered. Such maturation requires the association of GLB1 with protective protein/cathepsin A (PPCA) [29]. The GLB1-PPCA complex (680Kda), made up of four GLB1 and eight PPCA, is the major oligomeric form of GLB1 inside lysosomes [20]. The GLB1 enzyme, can also form a lysosomal complex with PPCA, NEU1, and N-acetylaminogalacto-6-sulfate sulfatase [20, 33]. Thus, considering the relatively mild phenotype of Patient 1 and his particular genetic assessment, a hypothetic role in assisting the aggregative processes of deficient GLB1 could be considered for the p.R109W amino acid change.

Also, at least in the patients with Italian origin (Patients 5 and 17), the relatively high occurrence of the p.R109W in the GM1 gangliosidosis patients can be linked to the p.R351X allele; thus a founder effect that gave rise to the spread of the two combined amino acid changes in Southern Italy can be proposed.

Sequence and structural data and in silico analyses also shed light on the p.S191N mutation. In silico analyses suggest the p.S191 amino acid to be positioned in a non fully conserved GLB1 region. Such a mutation, detected in combination with a stop change, was detected in a juvenile patient showing relatively high GLB1 residual activity (63 nmol/mg/h n.v. 117– 408 nmol/mg/h) (Patient 17, Tables 1-part II and 3). The patient’s late onset phenotype, the high residual enzyme activity and the absence of the mutation in 110 alleles from the normal population, indicate that such genetic alteration is a mutation and that it can be linked to late onset phenotypes.

Among all the reported mutations, the p.K578R, detected at a homozygous level in an alive 3 and 1/2 year female (Patient 15, Table 1-part I and 3), was previously described in the infantile phenotype [24]. GLB1 assay showed partial residual enzyme activity, but the course of the disease in this patient was rapid, with psychomotor regression by 1 year of age. However, the disease onset and the relatively prolonged survival do not meet the criteria of the infantile phenotype. The Patient’s phenotype is less severe than previously described for a GLB1 genotype, and although we cannot experimentally exclude a possible contribution of the associated triple X syndrome, her clinical course do not seem to be further worsened.

Patient 20 was homozygous for the c.1313G>A (p.G438E) mutation, previously described at a homozygous level both in Morquio B and in GM1 gangliosidosis type III patients [25, 26]. Our patient shows some features of skeletal dysplasia typical of Morquio syndrome i.e, thoracic deformity and short stature but no ligamentous laxity. Indeed, she showed neurological involvement including dystonia and anarthria. Miglustat treatment, undertaken in this patient for about 24 months, didn’t stop the general clinical worsening although we underline the short period of therapy.

The clinical, biochemical and genetic analyses of Patient 15 and 20 firmly suggest the complexity in determining genotype/phenotype correlations and in predicting the clinical course of late onset GM1 gangliosidosis/ Morquio B patients. Indeed, mutations such as the p.G438E, p.R201H, and p.S191N may be associated with late onset phenotypes (Morquio B, juvenile or adult GM1 gangliosidosis).

Clinical assessment of our cohort also suggests that some symptoms such as severe skeletal dysplasia and facial dysmorphims, strictly related to Morquio B syndrome and infantile GM1 gangliosidosis [34], can be present in late onset GM1 gangliosidosis.

Complicating eventual genotype phenotype correlations, the same genetic assessment (p.I51N/ p.R201H) was present in two patients (16 and 19), who exhibit quite different symptoms. In particular, Patient 19 presents severe skeletal involvement and corneal opacity, that are not shared by Patient 16.

Patients here reported with the Morquio B phenotype showed classical features of the disease, i.e. skeletal involvement, normal neurological development and keratan sulphate urinary excretion [17]. It is known that cell lines from patients with Morquio B also show a reduced capacity to assemble elastic fibers, linked to alterations in EBP [20, 35]. Thus, impaired elastogenesis with skeletal-connective tissue alterations, typical of Morquio syndrome, and cardiac involvement, can be related to both GLB1 and EBP alterations [22]. Patient 25’s clinical picture resembled that of Morquio B, particularly in view of the severe impairment of cardiac function that necessitated surgery with aortic valve replacement.

CONCLUSIONS

The tertiary structure of human GLB1 has not been resolved and only a previous homology model of human GLB1 was derived from the structure of the Bacteroides Thetaiotaomicron GLB1 protein has been reported [21]. Here we have used two structures of GLB1 from Penicillium and Bacteroides to produce an improved homology model of human GLB1.

Three-dimensional analysis and in silico outputs of mutated GLB1 proteins are helpful tools in defining patients’ phenotypes. However, a clear-cut phenotype classification between GM1 types I, II, III and Morquio B can be difficult. The considerations raised from the clinical and genetic assessment of our patients’ cohort together with the description of a neurological Morquio type B form [6], and with previous evaluations on the convergence between the different forms of GM1 gangliosidosis and between GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio B [7,22,25,34,36], warn physicians about the complications of defining disease severity in each case, and therefore of recommending any treatment that may be available. Polymorphisms could also play interesting roles on resulting enzyme activities and/or phenotypes.

At a glance, a continuum of phenotypes can be remarked in all carefully examined patients in whom GLB1 enzyme activity is deficient.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Italia, fondi ateneo (MURST ex 60% and Prin). We gratefully acknowledge the support of Associazione Italiana MPS e malattie affini. (AIMPS) and the Associazione Malattie Metaboliche Congenite Ereditarie (AMMEC). S.C.G acknowledges the support of the NIH (R01 DK76877).

Some samples were obtained from the “Cell Line and DNA Biobank from Patients Affected by Genetic Diseases” (G. Gaslini Institute) – Telethon Genetic Biobank Netwprk (Project No. GTB07001A).

Abbreviations

- GLB1

beta-galactosidase

- NB-DNJ, Miglustat, Zavesca

N-butyldeoxynojirimycin

- EBP

Elastin Binding Protein

- PPCA

protective protein/cathepsin A

- NEU1

lysosomal neuraminidase

REFERENCES

- 1.Suzuki Y, Oshima A, Namba E. β-Galactosidase deficiency (β-galactosidosis) GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio B disease. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 3775–3809. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caciotti A, Donati MA, Bardelli T, d'Azzo A, Massai G, Luciani L, Zammarchi E, Morrone A. Primary and Secondary Elastin-Binding Protein Defect Leads to Impaired Elastogenesis in Fibroblasts from GM1-Gangliosidosis Patients. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;167:1689–1698. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61251-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunetti-Pierri N, Scaglia F. GM1 gangliosidosis, review of clinical, molecular, and therapeutic aspects. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008;94:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson J. Incidence of the mucopolysaccharidoses in Northern Ireland. Hum. Genet. 1997;101:355–358. doi: 10.1007/s004390050641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson J, Crowhurst J, Carey B, Greed L. Incidence of the mucopolysaccharidoses in Western Australia. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2003;123A:310–313. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer FQ, Pereira Fdos S, Fensom AH, Slade C, Matte U, Giugliani R. New GLB1mutation in siblings with Morquio type B disease presenting with mental regression. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2009;96:148. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.11.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caciotti A, Bardelli T, Cunningham J, d'Azzo A, Zammarchi E, Morrone A. Modulating action of the new polymorphism L436F detected in the GLB1 gene of a type-II GM1 gangliosidosis patient. Hum. Genet. 2003;113:44–50. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0930-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giraldo P, Alfonso P, Atutxa K, Fernández-Galán MA, Barez A, Franco R, Alonso D, Martin A, Latre P, Pocovi M. Real-world clinical experience with long-term miglustat maintenance therapy in type 1 Gaucher disease: the ZAGAL project. Haematologica. 2009;94:1771–1775. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.008078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pineda M, Perez-Poyato MS, O'Callaghan M, Vilaseca MA, Pocovi M, Domingo R, Portal LR, Pérez AV, Temudo T, Gaspar A, Peñas JJ, Roldán S, Fumero LM, de la Barca OB, Silva MT, Macías-Vidal J, Coll MJ. Clinical experience with miglustat therapy in pediatric patients with Niemann-Pick disease type C: a case series. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;99:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wraith JE, Vecchio D, Jacklin E, Abel L, Chadha-Boreham H, Luzy C, Giorgino R, Patterson MC. Miglustat in adult and juvenile patients with Niemann-Pick disease type C: long-term data from a clinical trial. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;99:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masciullo M, Santoro M, Modoni A, Ricci E, Guitton J, Tonali P, Silvestri G. Substrate reduction therapy with miglustat in chronic GM2 gangliosidosis type Sandhoff: results of a 3-year follow-up. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010 Sep 4; doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliot-Smith E, Speak AO, Lloyd-Evans E, Smith DA, van der Spoel AC, Jeyakumar M, Butters TD, Dwek RA, d'Azzo A, Platt FM. Beneficial effects of substrate reduction therapy in a mouse model of GM1 gangliosidosis. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008;94:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinek A. Biological roles of the non-integrin elastin/laminin receptor. Biol. Chem. 1996;377:471–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Privitera S, Prody CA, Callhan JW, Hinek A. The 67kDa enzymatically inactive alternatively spliced variant of β-galactosidase is identical to the elastin/laminin-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6319–6326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinek A, Rabinovitch M. 67-kD elastin-binding protein is a protective "companion" of extracellular insoluble elastin and intracellular tropoelastin. J. Cell Biol. 1994;126:563–574. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.2.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mochizuki S, Brassart B, Hinek A. Signaling pathways transduced through the elastin receptor facilitate proliferation of arterial smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44854–44863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofer D, Paul K, Fantur K, Beck M, Roubergue A, Vellodi A, Poorthuis BJ, Michelakakis H, Plecko B, Paschke E. Phenotype determining alleles in GM1 gangliosidosis patients bearing novel GLB1 mutations. Clin. Genet. 2010;78:236–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarter JD, Burgoyne DL, Miao S, Zhang S, Callahan JW, Withers SG. Identification of Glu-268 as the catalytic nucleophile of human lysosomal beta-galactosidase precursor by mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:396–400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callahan JW. Molecular basis of GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio disease, type B Structure-function studies of lysosomal beta-galactosidase and the non-lysosomal beta-galactosidase-like protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1455:85–103. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(99)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pshezhetsky AV, Ashmarina M. Lysosomal multienzyme complex: biochemistry, genetics, and molecular pathophysiology. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2001;69:81–114. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(01)69045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morita M, Saito S, Ikeda K, Ohno K, Sugawara K, Suzuki T, Togawa T, Sakuraba H. Structural bases of GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio B disease. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;54:510–515. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrone A, Bardelli T, Donati MA, Giorgi M, Di Rocco M, Gatti R, Parini R, Ricci R, Taddeucci G, d'Azzo A, Zammarchi E. beta-galactosidase gene mutations affecting the lysosomal enzyme and the elastin-binding protein in GM1-gangliosidosis patients with cardiac involvement. Hum. Mutat. 2000;15:354–366. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200004)15:4<354::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE. Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion. Hum. Mutat. 2000;15:7–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boustany RM, Qian WH, Suzuki K. Mutations in acid beta-galactosidase cause GM1-gangliosidosis in American patients. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993;53:881–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bagshaw RD, Zhang S, Hinek A, Skomorowski MA, Whelan D, Clarke JT, Callahan JW. Novel mutations (Asn 484 Lys, Thr 500 Ala, Gly 438 Glu) in Morquio B disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1588:247–253. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(02)00172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paschke E, Lopez N, Eck T, Yoshida K, Maurel-Ollivier A, Doummar D, Caillaud C, Galanaud D, Billette de Villemeur T, Vidailhet M, Roubergue A. Dystonia and parkinsonism in GM1 type 3 gangliosidosis. Mov. Disord. 2005;20:1366–1369. doi: 10.1002/mds.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caciotti A, Donati MA, Procopio E, Filocamo M, Kleijer W, Wuyts W, Blaumeiser B, d'Azzo A, Simi L, Orlando C, McKenzie F, Fiumara A, Zammarchi E, Morrone A. GM1 gangliosidosis: molecular analysis of nine patients and development of an RT-PCR assay for GLB1 gene expression profiling. Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:204. doi: 10.1002/humu.9475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caciotti A, Donati MA, d'Azzo A, Salvioli R, Guerrini R, Zammarchi E, Morrone A. The potential action of galactose as a "chemical chaperone": increase of beta galactosidase activity in fibroblasts from an adult GM1-gangliosidosis patient. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2009;13:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang S, Bagshaw R, Hilson W, Oho Y, Hinek A, Clarke JT, Callahan JW. Characterization of beta-galactosidase mutations Asp332-->Asn and Arg148-->Ser, and a polymorphism, Ser532-->Gly, in a case of GM1 gangliosidosis. Biochem. J. 2000;348:621–632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo Conte L, Chothia C, Janin J. The atomic structure of protein–protein recognition sites. J. Molec. Biology. 1999;285:2177–2198. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glaser F, Steinberg DM, Vakser IA, Ben-Tal N. Residue frequencies and pairing preferences at protein–protein interfaces. Proteins. 2001;43:89–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma B, Nussinov R. Trp/Met/Phe hot spots in protein–protein interactions: potential targets in drug design. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007;7:999–1005. doi: 10.2174/156802607780906717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van der Spoel A, Bonten E, d’Azzo A. Processing of Lysosomal β-galactosidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:10035–100040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muthane U, Chickabasaviah Y, Kaneski C, Shankar SK, Narayanappa G, Christopher R, Govindappa SS. Clinical features of adult GM1 gangliosidosis: report of three Indian patients and review of 40 cases. Mov. Disord. 2004;19:1334–1341. doi: 10.1002/mds.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinek A, Zhang S, Smith AC, Callahan JW. Impaired elastic-fiber assembly by fibroblasts with either Morquio B disease or infantile GM1-gangliosidosis is linked to deficiency in the 67 kD spliced variant of β-galactosidase. Am. J. Hum. Gene.t. 2000;67:23–36. doi: 10.1086/302968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Grandis E, Di Rocco M, Pessagno A, Veneselli E, Rossi A. MR imaging findings in 2 cases of late infantile GM1 gangliosidosis. AJNR. 2009;30:1325–1327. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paschke E, Milos I, Kreimer-Erlacher H, Hoefler G, Beck M, Hoeltzenbein M, Kleijer W, Levade T, Michelakakis H, Radeva B. Mutation analyses in 17 patients with deficiency in acid beta-galactosidase: three novel point mutations and high correlation of mutation W273L with Morquio disease type B. Hum. Genet. 2001;109:159–166. doi: 10.1007/s004390100570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva CM, Severini MH, Sopelsa A, Coelho JC, Zaha A, d'Azzo A, Giugliani R. Six novel beta-galactosidase gene mutations in Brazilian patients with GM1-gangliosidosis. Hum. Mutat. 1999;13:401–409. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:5<401::AID-HUMU9>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santamaria R, Chabs A, Coll MJ, Miranda CS, Vilageliu L, Grinberg D. Twenty-one novel mutations in the GLB1 gene identified in a large group of GM1-gangliosidosis and Morquio B patients: possible common origin for the prevalent p.R59H mutation among gypsies. Hum. Mutat. 2006;27:1060. doi: 10.1002/humu.9451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oshima A, Yoshida K, Shimmoto M, Fukuhara Y, Sakuraba H, Suzuki Y. Human beta-galactosidase gene mutations in morquio B disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1991;49:1091–1093. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chakraborty S, Rafi MA, Wenger DA. Mutations in the lysosomal beta-galactosidase gene that cause the adult form of GM1 gangliosidosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1994;54:1004–1013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santamaria R, Blanco M, Chabs A, Grinberg D, Vilageliu L. Identification of 14 novel GLB1 mutations, including five deletions, in 19 patients with GM1 gangliosidosis from South America. Clin. Genet. 2007;71:273–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaye EM, Shalish C, Livermore J, Taylor HA, Stevenson RE, Breakefield XO. beta-Galactosidase gene mutations in patients with slowly progressive GM1 gangliosidosis. J. Child. Neurol. 1997;12:242–247. doi: 10.1177/088307389701200404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santamaria R, Chabs A, Callahan JW, Grinberg D, Vilageliu L. Expression and characterization of 14 GLB1 mutant alleles found in GM1-gangliosidosis and Morquio B patients. J. Lipid. Res. 2007;48:2275–2282. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700308-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]