Abstract

Fathers may feel dissatisfied with their ability to form a close attachment with their infants in the early postpartum period, which, in turn, may increase their parent-related stress. Our study sought to determine if an infant massage intervention assisted fathers with decreasing stress and increasing bonding with their infants during this time. To address the complex father–infant relationship, we conducted a pilot study using a mixed methodology approach. Twelve infant–father dyads participated in the intervention, and 12 infant–father dyads populated a wait-list control group. Paternal stress was measured using the Parenting Stress Index at baseline and at postintervention. We found infant massage instruction significantly decreased paternal stress. Our findings were also supported by the qualitative data and suggest fathers may benefit from applied postnatal education.

Keywords: fathers, infant massage, mixed-methods

Increasingly, today’s fathers want to be emotionally bonded with their babies. However, men often feel dissatisfied with their ability to form this meaningful relationship (Anderson, 1996b; Palkovitz & Palm, 2009; Pardew & Bunse, 2005). Fathers often worry they may be disadvantaged in developing this special relationship because women appear to have more opportunities and to be better equipped through various anatomical, physiological, and psychological adaptations (e.g., breastfeeding and greater responsiveness to infant cues; Anderson, 1996b; Salmon & Shackelford, 2007; Volk, Lukjanczuk, & Quinsey, 2005). However, although men generally lack these predisposing parental mechanisms, they are equally capable of potentially developing a successful parental relationship (Lamb, 2010). Fathers need to know that although their relationship with the child develops through different means, it can be equally as valid as the mother’s relationship. One proposed suggestion for helping fathers develop a relationship with their very young child is using the power of touch to help foster infant–father relationships (Field, 2001; Field et al., 2004; Field, Hernandez-Reif, Diego, Schanberg, & Kuhn, 2005).

Touch is our most primal sense and is associated with the largest organ in the human body—our skin. Of all the senses to develop, touch is the first and begins before the baby is born (Field, 2001). In the first few months of life, touch is used more often than hearing, sight, or smell as a way to learn about the physical world and to develop close, meaningful relationships (Field, 2001). Touch is a powerful communicator because it often mirrors our own feelings toward another individual (Hertenstein, Keltner, App, Bulleit, & Jaskolka, 2006). Ultimately, infants are able to sense how their parents feel about them by the manner in which they are touched (Field, 2001).

Touch is our most primal sense and is associated with the largest organ in the human body—our skin.

When humans are deprived of comforting touch, they are often at risk for a myriad of developmental issues such as small body stature, altered brain function, and the reproduction of stereotypic movements such as rocking or arm flapping (Carlson & Earls, 1997). In situations where infants are separated from their parents, such as war or famine, the detrimental effects of touch deprivation are evident. Blackwell (2000) states that at the beginning of the 20th century, in war-torn Germany, infant mortality in residential care was as high as 71.5%. The reported cause of death was termed hospitalism, which is described as a lack of stimulation by an adult caregiver rather than death by poor nutrition or insufficient medical care. A more modern example where touch deprivation occurs is in the neonatal intensive care unit. Infant massage has been employed in both of these kinds of environments and has successfully mediated the potentially negative consequences (Field, 2001).

With noted benefits of infant massage in clinical populations, Lorenz, Moyse, and Surguy (2005) provide a review of some of the important studies on the benefits of infant massage for healthy babies. In terms of physical health, infants who are massaged have fewer sleep problems in both quality and quantity of sleep (Field & Hernandez-Reif, 2001). One study reported that massage on the lower limbs improves cognitive development (Cigales, Field, Lundy, Cuadra, & Hart, 1997). In addition, symptoms of “colic” are often reduced for massaged infants, including discomfort in bowel movements and excessive crying. In terms of psychological benefits, most come from the reciprocal relationship formed between the massaged infant and the mother (Fogel-Schneider & Patterson, 2010), where massage provides a “special medium for relaxed communication” (Lorenz et al., 2005, p. 16). When mothers are able to understand their infants’ needs, they are able to respond in a more appropriate way, thus supporting synchrony and reciprocity in their developing relationship (Lorenz et al., 2005). Although these studies highlight the benefit of infant massage for both mothers and infants, much less is known about fathers.

Scholz and Samuels (1992) suggest that providing caregiving education, such as infant massage, for new fathers can greatly impact the quality of the infant–father relationship. In their study, participating fathers appeared to thrive on the emotional and motivational or attitudinal benefits of the increased opportunity to touch their infants. Similarly, Cullen, Field, Escalona, and Hartshorn (2000) found fathers who massaged their infants were more expressive, warm, and accepting in their interactions with their infants. Considering the potential benefits of infant massage for fathers, measuring perceived paternal stress is an area of research that appears to be underinvestigated.

STRESS AND PARENTING

The transition to parenthood is a developmental milestone that many men and women undertake in their lifespan. Although this transition is considered normal, it is also regarded as stressful (Sanders, Dittman, Keown, Farruggia, & Rose, 2010; Willinger, Diendorfer-Radner, Willnauer, Jörgl, & Hager, 2005). This transition is often characterized by a change in self and relationship perceptions. Research has found that most couples experience some decline in their marital satisfaction with the new parenting role (Johns & Belsky, 2007). This transition may be even more stressful for fathers as they often do not have the same physical, emotional, and social resources women have to cope with the new role (Johns & Belsky, 2007; Sanders et al., 2010).

Stress can lead to dysfunctional parenting (Bronte-Tinkew, Horowitz, & Carrano, 2010; Sanders et al., 2010). Parents who feel stressed by their parental role may react to their infants’ behavior, characteristics, and cues in an unfavorable way, which may negatively affect attachment (Neander & Engström, 2009; Parke, 2002). Most research in this area has focused on parents who have children with special needs, were born prematurely, or were in other crisis situations. Much less research has been conducted with parents in low-risk populations, even though we know parenting on its own can be very stressful (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2010).

Abidin’s (1992) research suggests parenting stress and attachment do not have a linear relationship. In most cases, high levels of stress lead to low levels of attachment; however, in cases of very low stress, parents may be disengaged in the process, which may also negatively impact their attachment quality (Willinger et al., 2005). Although it is generally accepted that higher levels of perceived stress will yield less secure attachments, both coping style and social supports act as mediators to attachment (Green, Furrer, & McAllister, 2007).

Fathers, in particular, may feel more perceived stress than mothers because they often feel unprepared to assume a parenting role (McBride, 1989; Sanders et al., 2010). Generally, fathers show less knowledge in the areas of normal child development, parenting skills, and sensitivity to infants’ needs (Doherty, Erickson, & LaRossa, 2006). McBride, Dyer, and Rane (2008) suggest fathers’ low level of parenting knowledge may be caused by a lack of a paternal role model in their own life, few social opportunities, and a lack of institutional support (McBride, 1989; McBride & Lutz, 2004). Because fathers experience a greater desire and social shift in their involvement in infant care, they may experience even greater stress in the transition to parenthood.

CURRENT STUDY

McBride (1989) found decreased perceived stress increases perceived parental competence. Infant massage may be the link between increased paternal competence (perceived or actual), lower levels of stress, and greater father involvement. To explore this idea further, we developed a quasi-experimental mixed-method study. Although the mixed-method approach has gained considerable interest in the research community over the last decade (Bergman, 2010; Sale, Lohfeld, & Brazil, 2002), this technique seems to be underused in research that examines fatherhood. The complex interplay of fathering and stress deserves to be investigated in a tradition that values depth in understanding while achieving cross-validation in a single study (Bergman, 2010; Sale et al., 2002). We predicted that fathers who experience the infant massage intervention will show decreased levels of parent and child domain related stress. No predictions were made regarding the qualitative data because the tradition of phenomenology expects that the participant’s experience will be presented free from the researcher’s bias (Groenewald, 2004). However, we did assume that qualitative data would provide a rich context for the efficacy of the intervention.

METHOD

Participants

A priori power analysis suggested a sample size of approximately 20 participants per group (see D’Amico, Neilands, & Zambarano, 2001; Osborne, 2006). Twenty-four infant–father dyads (12 dyads per group) were recruited for our study. The difference between the expected and actual number of participants was caused by the limitations of time and participant availability. To avoid potential bias, the decision to limit our sample size to 12 dyads per group was made prior to performing any statistical analyses.

The experimental group and the control group each had five male infants and seven female infants. The infants ranged in age from 5 to 14 months old, with a mean age of 8.08 months old. Caldera (2004) suggests that this is the age that most infants are able to form a secure attachment with both parents. The fathers ranged in age from 24 to 50 years old, with a mean age of 33.6 years old. Although we did not collect complete demographic data on the fathers, we observed from anecdotal observations during the study that they appeared to come from similar neighborhoods and places of work. For instance, most fathers in both groups had a postsecondary educational degree or higher (92% in the experimental group, 84% in the control group); considered themselves middle class (75% in the experimental group, 83% in the control group); and had no previous experience with infant massage (75% in the experimental group, 83% in the control group). All participating fathers lived with their infants, and 83.3% (in both groups) were married to the infants’ biological mothers. The participants were predominantly Caucasian.

Recruitment

To populate the experimental group, we recruited fathers through local advertising in the southwest region of Ontario, Canada. Three series of infant massage classes were conducted to fulfill requirements for study participation. The control group was populated using a snowball sampling technique. Eventually, 12 fathers were similarly recruited for the control group.

Measures

The Parenting Stress Index.

The Parenting Stress Index is a commercially available tool designed to measure parental stress in the parent–child relationship (Abidin, 1995). The test measures parental stress according to scores in three domains of stressors. The first domain of stressors represents the child’s characteristics: distractibility/hyperactivity, adaptability, reinforcement of the parent, demandingness, mood, and acceptability. The second domain of stressors represents the parent’s characteristics: competence, social isolation, attachment to the child, health, role restriction, depression, and spouse support. The total stress score is the sum of scores from both the child domain and the parent domain. The third domain of stressors is called “situational/demographic life stress” and includes, for example, marriage, pregnancy, or the death of a family member. The life stress score presents an overall view of stress in the parent–child unit. However, the life stress score should not be considered an outcome variable; instead, it should be considered a possible moderator of the parent and child domain stress scores.

Qualitative Interview.

The interview was conducted in a semistructured format, consisting of nine open-ended questions such as “How did your child respond to being massaged?” Only the fathers in the experimental group participated in the interview because the purpose of this qualitative technique was to understand fathers’ perceptions of infant massage participation. We analyzed the interview data according to Hycner’s (1999) five steps: (a) initial evaluation, bracketing, and reduction; (b) identifying units of meaning; (c) creating themes; (d) validating the data; and (e) weaving together the themes.

Intervention.

Instruction for infant massage was governed by guidelines from the International Association of Infant Massage (IAIM, 2005). The IAIM uses a combination of Indian massage, Swedish massage, yoga, and reflexology to create a comprehensive education program. The IAIM instructor never touches the infant; rather, the instructor demonstrates the strokes on a doll for the parents to mimic with their own child (Simpson, 2001).

Procedure

Fathers were recruited from the community to participate in either the 4-week infant massage class or the 4-week wait-list control group. Groups were populated based on the father’s availability to participate in the scheduled infant massage class. Fathers in both groups were asked to fill out the Parenting Stress Index and demographic information sheet at baseline. Postcondition, all fathers completed the Parenting Stress Index for the second time. The fathers in the experimental group were asked to participate in a qualitative interview. At the completion of the study, all participants received an honorarium, and participants in the control group were offered optional infant massage instruction.

RESULTS

We conducted a 2 (groups) × 4 (measures) × 2 (times) repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance. The measures were entered into the SPSS data analysis computer program as Child Domain, Parent Domain, Life Stress, and Total Stress. Prescores and postscores were entered as two levels. No significant violations of assumptions were observed. There was no significant main effect of group or time (p < .05); however, there was a significant time × group interaction (Pillai’s Trace = .38; F[3, 20] = 4.07, p = .02, η2 partial = .38). Two follow-up analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted on the time × group interaction effect.

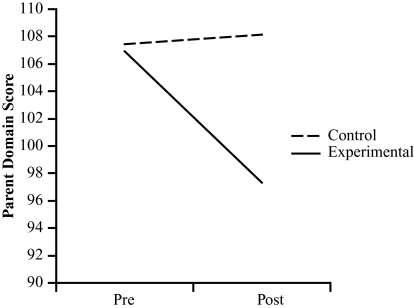

In the first follow-up ANOVA, a significant interaction main effect for the Parent Domain was found (F[1, 22] = 4.52, p = 0.05, η2 partial = .17). As depicted in Figure 1, the fathers in the control group scored slightly higher at time two than their baseline score. In addition, as illustrated in Table 1, the fathers in the experimental group reported a noticeable decline in stress scores after infant massage intervention. Thus, there was a significant interaction as well as a main effect for parental stress. In a second follow-up ANOVA, no significant effect was found in the Child Domain for group × time. In addition, no significant main effect was found for Life Stress. However, there was a nonsignificant trend (p = .07, η2 partial = .13) for the control group to experience lower life stress in the postphase, whereas the opposite appeared to be true for the experimental group (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Graph depicting prevalues and postvalues for control and experimental groups’ Parent Domain scores.

TABLE 1. Main and Interaction Effects for Parental Stress and Life Stress.

| Pre Mean (SD) | Post Mean (SD) | F | df | p | η2part | |

| Parental Stress | ||||||

| Experimental group | 106.83 (15.52) | 97.33 (13.88) | ||||

| Main effect | 4.52 | 1, 22 | .05 | .17 | ||

| Control group | 107.50 (22.62) | 108.08 (18.43) | ||||

| Time × condition interaction | 5.72 | 1, 22 | .03 | .21 | ||

| Life Stress | ||||||

| Experimental group | 5.67 ( 7.61) | 8.17 ( 8.82) | ||||

| Main effect | .01 | 1, 22 | .92 | .00 | ||

| Control group | 8.25 (5.88) | 6.00 ( 6.03) | ||||

| Time × condition interaction | 3.42 | 1, 22 | .07 | .13 |

Qualitative Interview

The major themes were extracted through qualitative analysis and are briefly reported here. Most fathers (58%) reported mixed feelings about being a father. Their relationships with their infants generally changed over time (67%), although they generally did not attribute such changes directly to infant massage (25%). Fathers were mostly positive about infant massage (58%), even if they felt it was challenging to perform at home (75%). Most infants enjoyed the massage (67%), and most fathers would recommend infant massage to other fathers (75%). Fathers reported a wide range of positive impressions about infant massage (e.g., getting closer to their infants and connecting with other fathers), although the only general complaint about the classes was that the instructor sometimes went too fast (17%). A further summary of the qualitative results are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2. Summary of Qualitative Results.

| Themes | % | |

| Question 1 | How do you experience being a father? | |

| Positive and negative | 58% | |

| Positive only | 25% | |

| Preconceived expectations | 17% | |

| Question 2 | How has your relationship with your child evolved since his or her birth? | |

| Change in child | 67% | |

| Change in self | 17% | |

| Change in both self and child | 8% | |

| Other | 8% | |

| Question 3 | How you felt in infant massage class? | |

| Positive experience | 58% | |

| Difficult, but positive overall | 34% | |

| Neutral | 8% | |

| Question 4 | Change in relationship since coming to class? | |

| Change in relationship, not due to infant massage | 42% | |

| No change in relationship | 33% | |

| Changes in self | 25% | |

| Question 5 | What was it like using this skill at home? | |

| Challenging | 75% | |

| Positive | 17% | |

| Other | 8% | |

| Question 6 | How did child respond to massage? | |

| Sometimes yes, sometimes no | 67% | |

| Tolerance | 33% | |

| Question 7 | Recommend infant massage class? | |

| Definitely | 75% | |

| Case-by-case | 25% | |

| Question 8 | Best part of experience? | |

| Babies and dads | 33% | |

| Learning something new | 25% | |

| Hanging out | 25% | |

| Other | 17% | |

| Question 9 | Comments | |

| No new comments | 50% | |

| No comment | 33% | |

| Functional (i.e., slow down instruction) | 17% |

DISCUSSION

The aim of our study was to understand the effectiveness of an infant massage intervention on fathers’ perceived level of stress and to understand fathers’ experience with the infant massage class. We determined that a mixed-method study was the most appropriate way to investigate this complex human relationship (see Bergman, 2010; Morgan, 2007). Overall, we found that infant massage classes significantly decreased paternal stress levels and that fathers reported a wide range of feelings and experiences from their participation in the class.

Quantitative Data

A significant interaction was found in the Parent Domain of the Parenting Stress Index. Fathers who experienced infant massage instruction considerably decreased their reported Parent Domain stress scores, postintervention. For fathers in the control group, Parent Domain stress scores actually increased slightly at time two. This suggests infant massage may be an effective way to decrease stress related to feelings of competence, isolation, attachment, personal health, feelings of depression, spousal support, and role restriction. Similarly, McBride (1991) found fathers reported higher levels of child care involvement, improved feelings of parental competence, and an overall greater involvement in their child’s development, postintervention. Doherty and colleagues (2006) found a similar benefit to fathers, reporting an increase in parenting skills and involvement during work days, postintervention. Teaching infant massage to fathers appears to improve their feelings of efficacy toward being a parent.

After applying the intervention, we found no difference between groups for stress in the Child Domain. It is possible that the Child Domain subscales of adaptability, acceptability, demandingness, mood, distractibility, and reinforcing the parent were too subjective to measure actual changes in the child, particularly physiological changes. It is also possible that change actually did occur, but the Parenting Stress Index was not sensitive enough to pick up on these changes. Somewhat related, it is also possible that fathers attributed the change in their infants to a change in themselves or in their relationship. Regardless, the fathers did not perceive much change in their infants, which may explain some of their qualitative responses.

Abidin (1995) claims the Life Stress scale of the Parenting Stress Index can act as an indicator of actual stressors on the family unit, such as divorce, pregnancy, and legal problems. In our study, fathers in the experimental group reported experiencing greater external life stress, postintervention; however, their scores in the Parent Domain declined. The fathers in the control group reported experiencing greater life stress preintervention, and their Parent Domain scores also slightly decreased. Although both groups lowered their Parent Domain stress scores, fathers in the infant massage group experienced a noticeably greater, and statistically significant, reduction in their parent domain stress. It is possible that the intervention may have acted as an extra safeguard for the experimental group, considering their Life Stress scores increased postintervention. As noted, these results should be described as statistical trends because they only approach significant levels (they might have reached significance with a larger sample size).

Qualitative Data

When asked how the fathers felt in the infant massage class, 92% described an overall positive experience. However, 34% of the fathers’ responses also included some descriptions of difficulty. For example, one father reported that he initially felt awkward in the class because he had never considered infant massage before. This described difficulty may be a reflection of what some researchers are reporting in the literature: Men’s participation in baby massage classes is still limited (Adamson, 1996; Mackereth, 2000, 2003). It is possible that some of this initial difficulty could have been resolved had the class focused more time on deconstructing the notion that fathers are on the periphery of nurturing touch.

Two notable themes emerged from the data on changes in the father–infant relationship since the start of the infant massage class. The first theme is characterized by the fathers’ perception of a change in the baby. Forty-two percent of fathers reported a change and noted the baby getting older and being able to do more things as a reason for their evolving relationship. The notion of increased age playing a role in increased bonding is not new and is deeply entrenched in the messages fathers receive about fatherhood (Grossmann et al., 2002). Interestingly, none of these fathers in our study indicated learning infant massage as a factor in their new relationship. It is possible that this prevailing notion of delayed bonding is the catalyst behind no perceived change in the child on the Parenting Stress Index.

The fathers who perceived changes in themselves as a reason for an overall change in their relationship with the infant did, however, mention infant massage as playing a significant role. This finding is supported by the quantitative data collected from our study. Twenty-five percent of fathers reported a change in self after attending. One father reported:

[I]f my wife had asked me to take [my daughter] out for forty-five minutes I would say, “Are you crazy? She is still breast-fead [sic], Im [sic] not going to do that,” but now I am a lot more willing to keep her for an hour.

Considering only 25% of fathers saw themselves as a reason for change supports the quantitative data and further suggests that the fathers might not have always been aware of the changes that were happening in themselves and their child.

The fathers were asked what it was like using the skill of infant massage at home. Seventy-five percent of responses included the perception of infant massage at home being challenging. Some fathers described not wanting to disrupt the established bedtime routine or already having set “daddy” activities; therefore, finding the time to schedule a daily infant massage was not realistic. It is possible that the fathers in the experimental group were already set in their routines and were less willing to incorporate a new activity into their schedule.

When asked how their baby responded to being massaged, most fathers’ answers were characterized by both enjoyment and disinterest. Most of the fathers said it depended on the time of day, the body part being massaged, and whatever else was going on. The remaining 33% said the infant “tolerated it,” meaning the infant acted neutral to the massage and continued doing whatever he or she was doing. This perceived indifference may have come as a surprise to some of the fathers because many noted they thought the child would enjoy it more than they appeared to. These findings do not seem to be supported in the literature, which seems to only report on the more positive responses (Adamson, 1996; Clark, Gibb, Hart, & Davidson, 2002; Mackereth, 2003). From an infant massage instructor’s point of view, these findings are encouraging because they show the fathers were paying attention to engagement and disengagement cues and learning about personal preferences (IAIM, 2005). This viewpoint is plausable and supported by the decrease in Parent Domain stress scores on the Parenting Stress Index.

Matthey and Barnett (1999) indicate a need for father participation in postpartum baby classes; however, they claim much less is known about how fathers view their educational needs. In our study, we discovered that 75% of participating fathers said they would highly recommend infant massage class to other fathers. Similar to Mackereth’s (2003) findings, the data in our study revealed fathers perceived the infant massage instruction as a great bonding tool and a gateway to becoming more comfortable with their baby. This finding may be an important benefit to father–infant massage, and an increase bonding with other fathers could be part of the reason why fathers felt less paternal stress (e.g., feeling less isolated).

The fathers’ report of feeling less isolated is reinforced by the interview’s question regarding the best part of the experience of attending an infant massage class: Thirty-three percent of the fathers said the class offered the chance to meet other dads and babies. Many of the fathers reported that they felt isolated in their fatherhood role because they did not know other fathers or children and they had few father-focused opportunities—a finding that is supported in the current literature (Deave & Johnson, 2008; Doherty et al., 2006). Twenty-five percent of the fathers in our study reported that they enjoyed learning something new. Clark et al. (2002) found that group massage instruction also helps enrich parenting experiences because parents are able to learn through shared discussions. The remaining 25% of fathers in our study said the best part of the class experience was spending one-on-one time with their child. The fathers appreciated the dedicated time they had on their own with their infants, a time that was not set aside just to “give mommy a break.” This finding suggests baby massage is an activity fathers can participate in that may give them the connection they desire to be more comfortable in their parenting role.

Study Limitations

A few logistical and feasibility issues are associated with our study. A potential limitation is the short timespan between premeasures and postmeasures. A lengthier longitudinal study may strengthen any statements about the lasting effects of the infant massage intervention and how it ultimately impacts the relationship between fathers and their infants. The second limitation is nonrandomization. Randomization of participants to control and experimental groups was not possible in our study because of slow recruitment. Thus, a quasi-experimental design was considered to be the most feasible way to move the project forward. The third logistical issue is that one primary person was responsible for designing the research, collecting the data, interviewing the participants, and providing the intervention. To improve rigor, the individual providing the intervention and administering the measures should be “blind” to the study’s purpose so as not to bias the participants’ responses in any way. Finally, the relatively small sample size warrants caution in how generalizable our results are. The fact that repeated measures designs reduce variability and, thus, improve power (Howell, 2010) gives us greater confidence in the validity of our study’s small sample, quasi-experimental design. In fact, power was not a direct issue because we found significant results (that, by definition, are unlikely to be caused by random chance given their low p values). Nevertheless, some caution about the validity of our study’s results beyond the sample is warranted until the results are replicated with a larger and more diverse sample of fathers and infants, particularly participants representing different cultural groups.

Conclusions and Recommendations for Further Research

The father–infant relationship has gained considerable attention in the past few decades. Research has uncovered the need to investigate the father–infant relationship in its own framework rather than as an alternative to mother–infant theory. The relationship between father and infant is complex. Although a new culture of fatherhood appears to be emerging, the practice of fatherhood has not caught up to the idea of men as involved participants (Lamb, 2010; Rustica & Abbott, 1993). Men need to know more about the transition to fatherhood and skill development that will assist in forming positive relationships with their infants (Anderson, 1996a; Parke, 2002).

Infant massage appears to be a viable option for teaching fathers caregiving sensitivity. This study, while reporting on a brief intervention, suggests that participating fathers were helped by increasing their feelings of competence, role acceptance, spousal support, attachment, and health and by decreasing feelings of isolation and depression. Although not all fathers saw the direct benefit of infant massage instruction, they did note they enjoyed participating in an activity that gave them special time with their infants and appreciated the opportunity to meet other fathers. The results of our study have clear implications for fathers and for professionals and policy makers who work with fathers. First, fathers are clearly quite capable of being engaged parents, and father–infant massage may represent a valuable tool to assist fathers in that regard. Second, infant massage appears to be an effective way to engage fathers and improve their parenting experiences, even in the face of potential increases in general life stresses. Finally, infant massage classes appear to offer fathers the positive experience of meeting other fathers and enjoying the opportunity to share their fathering experiences.

Infant massage classes appear to offer fathers the positive experience of meeting other fathers and enjoying the opportunity to share their fathering experiences.

Biography

CAROLYNN DARRELL CHENG is a research coordinator at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada. Her master’s degree is complimented by certifications in child life and infant massage instruction. ANTHONY A. VOLK is a developmental psychologist interested in the area of parenting and child development. A strong believer in multidisciplinary studies, Dr. Volk’s overall interest is to gain an evolutionary, neurological, medical, cultural, social, and historical understanding of why parents and children do what they do. ZOPITO A. MARINI is a developmental and educational psychologist. Using a biopsychosocial perspective, Dr. Marini is interested in investigating the cognitive mechanisms and social processes underlying the development of sociocognitive abilities by examining the mediating and moderating impact of psychosocial factors, such as anxiety, antisocial beliefs, temperament, evolutionary adaptations, friendship quality, and parenting practices on children’s adjustment.

REFERENCES

- Abidin R. R. (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21(4), 407–412 doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2104_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abidin R. R. (1995). Parenting Stress Index: Professional manual (3rd ed.). Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources [Google Scholar]

- Adamson S. (1996). Teaching baby massage to new parents. Complementary Therapies in Nursing & Midwifery, 2(6), 151–159 doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A. M. (1996a). Factors influencing the father–infant relationship. Journal of Family Nursing, 2(3), 306–324 doi: 10.1177/107484079600200306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A. M. (1996b). The father–infant relationship: Becoming connected. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses, 1(2), 83–92 doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.1996.tb00005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman M. M. (2010). On concepts and paradigms in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(3), 171–175 doi: 10.1177/1558689810376950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell P. (2000). The influence of touch on child development: Implications for intervention. Infants and Young Children, 13(1), 25–39 [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J., Horowitz A., & Carrano J. (2010). Aggravation and stress in parenting: Associations with coparenting and father engagement among resident fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 31(4), 525–555 doi: 10.1177/0192513X09340147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caldera Y. M. (2004). Parental involvement and infant–father attachment: A Q-set study. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice about Men as Fathers, 2(2), 191–210 doi: 10.3149/fth.0202.191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M., & Earls F. (1997). Psychological and neuroendocrinological sequelae of early social deprivation in institutionalized children in Romania In Carter C. S., Lederhendler I. I., & Kirkpatrick B. (Eds.), The integrative neurobiology of affiliation (pp. 419–428). New York, NY: New York Academy of Sciences; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigales M., Field T., Lundy B., Cuadra A., & Hart S. (1997). Massage enhances recovery from habituation in normal infants. Infant Behavior and Development, 20(1), 29–34 doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(97)90058-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C., Gibb C., Hart J., & Davidson A. (2002). Infant massage: Developing an evidence base for health visiting practice. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing, 6(3–4), 121–128 doi: 10.1016/S1361-9004(02)00089-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen C., Field T., Escalona A., & Hartshorn K. (2000). Father–infant interactions are enhanced by massage therapy. Early Child Development and Care, 164(1), 41–47 doi: 10.1080/0300443001640104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E. J., Neilands T. B., & Zambarano R. (2001). Power analysis for multivariate and repeated measures designs: A flexible approach using SPSS MANOVA procedure. Behavior Research Methods, 33(4), 479–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deave T., & Johnson D. (2008). The transition to parenthood: What does it mean for fathers? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 63(6), 626–633 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty W. J., Erickson M. F., & LaRossa R. (2006). An intervention to increase father involvement and skills with infants during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(3), 438–447 doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T. (2001). Touch. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- Field T., & Hernandez-Reif M. (2001). Sleep problems in infants decrease following massage therapy. Early Child Development and Care, 168, 95–104 doi: 10.1080/0300443011680106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field T., Hernandez-Reif M., Diego M., Feijo L., Vera Y., & Gil K. (2004). Massage therapy by parents improves early growth and development. Infant Behavior & Development, 27(4), 435–442 doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2004.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field T., Hernandez-Reif M., Diego M., Schanberg S., & Kuhn C. (2005). Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. International Journal of Neuroscience, 115(10), 1397–1413 doi: 10.1080/00207450590956459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel-Schneider E., & Patterson P. P. (2010). You’ve got that magic touch: Integrating the sense of touch into early childhood services. Young Exceptional Children, 13(5), 17–27 doi: 10.1177/1096250610384706 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green B. L., Furrer C., & McAllister C. (2007). How do relationships support parenting? Effects of attachment style and social support on parenting behavior in an at-risk population. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40(1–2), 96–108 doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9127-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald T. (2004). A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 1–26 Retrieved from http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/3_1/html/groenewald.html [Google Scholar]

- Grossman K., Grossman E. K., Fremmer-Bombik E., Kingler H., Scheuerer-Englisch H., & Zimmermann P. (2002). The uniqueness of the child–father attachment relationship: Fathers’ sensitive and challenging play as a pivotal variable in a 16-year longitudinal study. Social Development, 11(3), 301–337 doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hertenstein M. J., Keltner D., App B., Bulleit B. A., & Jaskolka A. R. (2006). Touch communicates distinct emotions. Emotion, 6(3), 528–533 doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell D. C. (2010). Statistical methods for psychology (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning [Google Scholar]

- Hycner R. H. (1999). Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data In Bryman A. & Burgess R. G. (Eds.), Qualitative research (Vol. 3, pp. 143–164). London, UK: Sage [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Infant Massage (2005). Certified infant massage instructor teaching guide. Ventura, CA [Google Scholar]

- Johns S. E., & Belsky J. (2007). Life transitions: Becoming a parent In Salmon C. A. & Shackelford T. K. (Eds.), Family relationships: An evolutionary perspective (pp. 71–90). New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Lamb M. E. (2010). The role of the father in child development (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz L., Moyse K., & Surguy H. (2005). The benefits of baby massage. Pediatric Nursing, 17(2), 15–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackereth P. A. (2000). Tough places to be tender: Contracting for happy or ‘good enough’ endings in therapeutic massage/bodywork? Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery, 6(3), 111–115 doi: 10.1054/ctnm.2000.0489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackereth P. A. (2003). A minority report: Teaching fathers baby massage. Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery, 9(3), 147–154 doi: 10.1016/S1353-6117(03)00037-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthey S., & Barnett B. (1999). Parent–infant classes in the early postpartum period: Need and participation by fathers and mothers. Infant Mental Health Journal, 20(3), 278–290 doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McBride B. A. (1989). Stress and fathers’ parental competence: Implications for family life and parent educators. Family Relations, 38(4), 385–389 Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/585742 [Google Scholar]

- McBride B. A. (1991). Parent education and support programs for fathers: Outcome effects on paternal involvement. Early Child Development and Care, 67, 73–85 doi: 10.1080/0300443910670107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McBride B. A., Dyer W. J., & Rane T. R. (2008). Family–school partnerships in early childhood programs: Don’t forget fathers/men In Cornish M. (Ed.), Promising practices for partnering with families in the early years (pp. 41–57). Greenwich, CT: Information Age [Google Scholar]

- McBride B. A., & Lutz M. M. (2004). Intervention: Changing the nature and extent of father involvement In Lamb M. E. (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (4th ed., pp. 446–475). New York, NY: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. L. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: Methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 48–76 doi: 10.1177/2345678906292462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neander K., & Engström I. (2009). Parents’ assessment of parent–child interaction interventions—A longitudinal study in 101 families. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 3(1), 8 doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-3-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne J. W. (2006). Power analysis for multivariate and repeated measurements designs via SPSS: Correction and extension of D’Amico, Neilands, and Zambarano (2001) Behavior Research Methods, 38(2), 353–354 doi: 10.3758/BF03192787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovitz R., & Palm G. (2009). Transitions within fathering. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, & Practice about Men as Fathers, 7(1), 3–22 doi: 10.3149/fth.0701.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pardew E. M., & Bunse C. (2005). Enhancing interaction through positive touch. Young Exceptional Children, 8(2), 21–29 doi: 10.1177/109625060500800203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parke R. D. (2002). Fathers and families In Bornstein M. H. (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Being and becoming a parent (Vol. 3, pp. 27–73). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates [Google Scholar]

- Rustica J. G., & Abbott D. (1993). Father involvement in infant care: Two longitudinal studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 30(6), 467–476 doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(93)90018-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sale J. E., Lohfeld L. H., & Brazil K. (2002). Revisiting the quantitative–qualitative debate: Implications for mixed-methods research. Quality & Quantity, 36(1), 43–53 doi: 10.1023/A:1014301607592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon C. A., & Shackelford T. K. (2007). Toward an evolutionary psychology of the family In Salmon C. A. & Shackelford T. K. (Eds.), Family relationships: An evolutionary perspective (pp. 3–15). New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Sanders M. R., Dittman C. K., Keown L. J., Farruggia S., & Rose D. (2010). What are the parenting experiences of fathers? The use of household survey data to inform decisions about the delivery of evidence-based parenting interventions to fathers. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41(5), 562–581 doi: 10.1007/s10578-010-0188-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz K., & Samuels C. (1992). Neonatal bathing and massage intervention with fathers, behavioral effects 12 weeks after birth of the first baby: The Sunraysia Australia intervention project. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 15(1), 67–81 [Google Scholar]

- Simpson R. (2001). Baby massage classes and the work of the International Association of Infant Massage. Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery, 7(1), 25–33 doi: 10.1054/ctnm.2000.0510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk A. A., Lukjanczuk J. M., & Quinsey V. L. (2005). Influence of infant and child facial cues of low body weight on adults’ ratings of adoption preference, cuteness, and health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26(5), 459–469 doi: 10.1002/imhj.20064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willinger U., Diendorfer-Radner G., Willnauer R., Jörgl G., & Hager V. (2005). Parenting stress and parental bonding. Behavioral Medicine, 31(2), 63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]