Abstract

The purpose of this study was to describe the reported perceptions of six midwife participants at different stages of their engagement in a multiphase process of adopting a new model of prenatal care. Midwives were interviewed at five different stages during the process of implementing CenteringPregnancy, a model of group prenatal care. The research methodology used in this study was phenomenology. The conceptual framework for exploring the participants’ perceptions was based on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s patient-centered model and on the International Institute for Restorative Practices’ empowerment model. The five themes that emerged from the midwives’ experiences mirrored the stages of change health education model. Suggestions for the implementation and sustainability of the CenteringPregnancy model of care are provided based on the five themes that emerged from this study’s findings.

Keywords: CenteringPregnancy, pregnancy, prenatal care, qualitative research

CenteringPregnancy (CP), a model of group prenatal care, is being used as an alternative to traditional prenatal care by midwives and other providers in many different locations. Research and evaluation studies of CP have found many positive outcomes for pregnant women and their babies; however, few studies have explored midwives’ perceptions of the CP model or the process of implementing it.

For more information about CenteringPregnancy, visit http://www.centeringhealthcare.org/pages/centering-model/pregnancy-overview.php

The CP model of prenatal care has been implemented and used in more than 300 sites in the United States and in several foreign countries (S. Rising, personal communication, July 14, 2009). This model of group prenatal care as envisioned by Rising in 1994 incorporates the three components of care—education, health assessment, and supportive care—into one entity, with the goal of empowering women to take responsibility for their care (Baldwin, 2006; Rising, 1998; Rising, Kennedy, & Klima, 2004). CP takes women out of traditional exam rooms and brings them into a group setting for education, support, and care (Rising, 1998; Rising et al., 2004). In CP, standard risk assessment—including a physical examination to determine fundal height, fetal heart tones, and a review of interim history—is conducted individually but within a group setting. Following the completion of each group member’s physical examination at the beginning of each visit, group discussion is facilitated by the health-care provider. Each session of the 8–10 meetings of CP, which last approximately 90–120 minutes each, have a general educational component, combining all elements of prenatal care and childbirth education into one setting (Baldwin, 2006; Walker & Worrell, 2008). CP offers pregnant women many hours of contact and support from their health-care provider as opposed to the usual 10 or 15 minutes in the exam room (Walker & Worrell, 2008). Studies have shown that CP contributes to greater client knowledge (Baldwin, 2006; Ickovics et al., 2007; Rising et al., 2004), social support (Baldwin, 2006; Kennedy et al., 2009; Rising, 1998; Rising et al., 2004), and satisfaction when compared with traditional care (Grady & Bloom, 2004; Ickovics et al., 2007; Klima, Norr, Vonderheid, & Handler, 2009; Novick, 2004; Robertson, Aycock, & Darnell, 2009; Teate, Leap, Rising, & Homer, 2011). Although limited in numbers, the research outcomes of CP include reduced preterm birth rates (Ickovics et al., 2003; Ickovics et al., 2007; Novick, 2004; Skelton et al., 2009), increased weight of preterm infants (Ickovics et al., 2003; Ickovics et al., 2007), greater initiation of breastfeeding (Klima et al., 2009; Skelton et al., 2009; Westdahl, Kershaw, Rising, & Ickovics, 2008), perception of better preparation for labor and birth (Ickovics et al., 2003), better weight gain in pregnancy (Klima et al., 2009; Novick, 2004), more prenatal visits (Ickovics et al., 2003; Klima et al., 2009; Novick, 2004), and cost-neutrality of the model (Cox, Obichere, Knoll, & Baruwa, 2006).

CenteringPregnancy takes women out of traditional exam rooms and brings them into a group setting for education, support, and care.

The purpose of our qualitative explorative study was to examine midwives’ thoughts, feelings, and perceptions as they first contemplated attempting the CP model of care, as they continued with attendance at educational training workshops, and as they completed work with their first CP group. We were also interested in the sustainability of the CP model of prenatal care; we believed that by following midwives from initial exploration of the model through training and professional development to the completion of their first series of implementing CP, issues would be addressed that would improve outcomes of the model.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

We based the conceptual framework for our study on evidence that the CP model of group prenatal care is patient-centered and empowering to both patient and provider. The models that substantiate these concepts are the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s patient-centered model and the International Institute for Restorative Practices’ (IIRP) empowerment model.

The CP model of group prenatal care embodies the definition of patient-centered care as evidenced by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (2010) criteria, which include meeting the needs and preferences of patients, allowing shared decision making, and viewing patients and their families as partners in health-care design.

The Institute of Medicine’s (2001) report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” identifies patient-centered care as an essential foundation for quality in health care. The way care is delivered is considered as important as the care itself. In its seminal report, the Institute of Medicine identifies the concept of patient-centered care as one of the six aims for health-care reform.

According to Bodenheimer and Grumbach (2007), patient-centered care is, in essence, about partnerships and is supported by the leaders of the New Quality Movement in health care whose objectives include the following: encouraging patients to be more participatory, allowing shared power and responsibility, supporting patient autonomy and individuality, and attending to clinician–patient relationships. The purposes of patient-centered care are improving outcomes, creating higher employee satisfaction, offering mutual respect, and meeting the needs and preferences of patients. Patient-centered care, as a partnership, also involves providers in ways that can be transformative. The IIRP uses the framework of patient-centered care as a “restorative practice” in health-care redesign. Patient-centered care engages practitioners in support of autonomy. The word “restorative” speaks to the concept of power, specifically to restoring power. In the context of the health-care delivery system, it refers to restoring the balance of power between patient and clinician. Empowerment is a process that encourages and creates an environment where individuals regain control over their health-care decisions. In health care, empowerment is a journey that encourages patients to take responsibility for their own health behaviors; in a group setting, empowerment gives the necessary support to change behaviors. Thus, restorative and empowerment are synonymous (Wachtel & McCold, 2001).

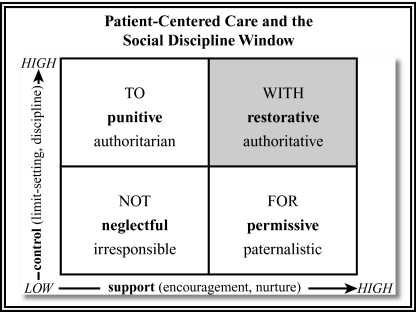

According to the IIRP, the fundamental unifying hypothesis of restorative practices is simple: Human beings are happier, more cooperative and productive, and more likely to make positive changes in their behavior when individuals in positions of authority do things with them rather than to them or for them. The IIRP’s concept of the “Social Discipline Window” is both a map and a vehicle for change (Wachtel & McCold, 2001).

When the health-care delivery system and health-care providers operate within the “with” window, both patients and providers become mutually respected partners, and empowerment is allowed to happen (Wachtel & McCold, 2001). Because the CP model is both a facilitated group and a patient-centered model, it operates within the “with” social discipline window (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient-centered care and the Social Discipline Window. Adapted from “Restorative Justice in Everyday Life” by T. Wachtel and P. McCold, 2001, in H. Strang and J. Braithwaite (Eds.), Restorative Justice in Civil Society (pp. 114–129), New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted with permission from Paul McCold, PhD.

When the health-care delivery system and health-care providers operate within the “with” window, both patients and providers become mutually respected partners and empowerment is allowed to happen.

Our study was based on the idea that midwives participate in a paradigm shift from traditional one-on-one care to group care, and as a result, the midwives become empowered themselves as they empower their clients.

METHODS

We obtained permission to conduct our study from two institutional review boards: one where one of us is employed, and another from a hospital in the Midwest, where two of the midwives who participated in the study were working. We also obtained permission letters from the chief executive officers of the other midwifery practices located in the southern and northeast regions of the United States. The six midwives who participated in our study were recruited from CP educational workshops, and they signed informed consent forms indicating their understanding of the study and their willingness to participate.

Using a qualitative approach in obtaining information from the midwives allowed us to listen to the midwives’ voices concerning their thoughts, feelings, and perceptions as they implemented CP. Interviews were conducted at five separate times during the process and in the following sequence:

-

1

Before and during the educational training for CP,

-

2

During the month prior to the first CP group session,

-

3

After the first CP group session,

-

4

After the fifth CP group session or halfway through the CP group sessions, and

-

5

After the final CP group session.

Questions were asked in a semistructured way to allow the midwives to freely verbalize their ideas and concerns about the CP process. As the two primary investigators, each of us interviewed three midwives. Some interviews were conducted face-to-face and others were conducted by telephone because of geographic distance. Interviews were transcribed verbatim.

The focus of our study was to capture the lived experience of the midwives as they used the CP model. The use of a qualitative approach is based on phenomenology, “a qualitative research tradition, with roots in philosophy and psychology, that focuses on the lived experience of humans,” as a way to explore and comprehend people’s perceptions of certain aspects of their lives (Polit & Beck, 2009b, p. 761). We carefully analyzed all of the interviews using Colazzi’s method for extraction and exactness of significant statements (Polit & Beck, 2009a). We organized clusters of data into themes, which formed descriptive pictures of the lived experiences of the midwives as they implemented CP into their practices. Each theme was validated for accuracy by the six midwives who participated in the study.

RESULTS

Six midwives from five different midwifery practices participated in our study. The midwifery practices were located in the U.S. regions of the Midwest, Northeast, and South. Participants were all female, ranged in age from 32 to 56 years old and had varying years of midwifery experience, ranging from 5 to 14 years. Patient populations also varied from a private practice model to community health centers and community hospitals.

With data collection and analysis, it became apparent that the findings along each step of the process of implementing CP mirrored Prochaska and DiClemente’s (1983) stages of change, also referred to as the transtheoretical health education model. This model was first introduced in 1983 to describe steps in the smoking-cessation process and has been used in a plethora of studies to describe the process that individuals move through as they change a behavior. Briefly, this model discusses the stages of change that individuals used as they participate in a change of behavior in their lives. First, no change is anticipated, followed by contemplation of a change, then active participation occurs to change the behavior, engagement in the new behavior is accepted, and lastly, maintenance of the change of behavior is sustained/attempted (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983). Table 1 lists the assessment questions we asked, along with the corresponding stage within the stages of change process, the five themes that emerged, and the implications for practice.

TABLE 1. Questions, Themes, and Implications for Practice.

| Assessment Questions | Themes | Implications for Practice |

| 1. How do you perceive the current prenatal experience for you and your clients? (Precontemplation stage) | My current practice is just fine: No intention of changing | Change is difficult for all |

| Important to look at ways to improve prenatal care | ||

| 2. What worked and did not work in your process of planning and implementing CP into your midwifery practice? (Contemplation stage) | Thinking about giving CP a try: Considering changing | The CP educational process is essential |

| 3. What worked and did not work during your first CP group session? (Active Participation stage) | Anxiety and stress about a new model of care: Engaged in the paradigm shift from traditional to group care | Engaged in the paradigm shift from individual to group care |

| 4. You have now completed five CP group sessions. How are the sessions going? (Action stage) | Confidence and empowerment with the group: Actively engaged in new behavior | Repetition of group facilitation process is easier over time |

| 5. You have now completed your first full CP group. How do you feel about this? (Maintenance stage) | Looking to the future: Committed to the CP model and wanting to sustain change | Desire to sustain the CP model over time |

| Difficult to return to traditional care |

Note. CP = CenteringPregnancy model of group prenatal care.

Assessment Questions

We asked the midwives the following questions at five different periods during the process:

-

1

Before and during the educational training for CP (Precontemplation stage): How do you perceive the current prenatal care experience for you and your clients?

-

2

During the month prior to the first CP group session (Contemplation stage): What worked and did not work in your process of planning and implementing CP into your midwifery practice? How did these issues relate to the information that you received during the formal training process for CP? What was the most challenging and why? How was it resolved? What worked and did not work?

-

3

After the first CP group session (Active Participation stage): What worked and did not work during your first CP group session? What did you feel good about and what would you have done differently? What are your thoughts and feelings about your group facilitation experience? What would have been helpful for your first group to be more successful? How many women were recruited and how many showed up?

-

4

After the fifth CP group session or halfway through the CP group sessions (Action stage): You have now completed five CP group sessions. How are the sessions going? How is group facilitation going? How do you feel about your role in this? Are you comfortable with this?

-

5

After the final CP group session—group session number 10 (Maintenance stage): You have now completed your first full CP group. How do you feel about this? What worked and did not work for you? What would you do differently with your next group? What advice would you give to others contemplating beginning CP groups? Did the experience meet your expectations? What concerns remain? How would you resolve issues as you move forward with more groups?

Emergent Themes

Five themes emerged from the data and corresponded with the particular period of the interview process. Each of the themes is presented in the subsequent texts and is illustrated by statements from the midwives in response to the interview questions.

Theme 1—My current practice is just fine: No intention of changing (Precontemplation stage).

The midwives described their practices, explaining that things seemed to be going fine and that they were not considering a change in the way they were delivering care. Some of their comments included, “I am very happy with the way I provide care right now” and “I don’t think the system is broken.” Only one of the midwives had actually been exposed to CP in midwifery school, and she was not sure that the CP model would work in her new setting. She said, “I’ve heard a little about this [CP], and don’t think I would be very good at it [facilitation].” Similarly, some of the midwives stated that they were very skeptical of the facilitation process in the CP model, as demonstrated in the following statements:

I am afraid that I would not be a good group leader.

The facilitation thing is scary.

Facilitation. Whoa, that is not for me.

Theme 2—Thinking about giving CP a try: Considering changing (Contemplation stage).

All six midwives were at least somewhat familiar with the CP method. Some had read an article about CP and/or had attended meetings where midwives discussed the CP model. During and after attending our study’s CP educational training workshop, the midwives embraced the CP model for its empowerment of themselves, staff, and patients. The following comments from some of the midwives during the second interview reflected their eagerness to adopt the CP model of care in their practice:

I am committed to this model of care.

I believe that this model is hopeful and transformative.

I want to get away from the politics in the office.

I want to invigorate myself and the staff.

I really want to help women help themselves.

I believe that this group model will help my patients develop more positive health behaviors.

It became obvious to the midwives that the CP model might be a very satisfying approach to providing prenatal care. For example, some of the midwives voiced the following statements:

As a provider, I can’t give the kind of care that I want to give with traditional care.

The group will give me more time with my patients.

I want to give more support to my clients and their families.

I say the same thing over and over to each of my patients.

I would like to connect with women/families in a different way.

Theme 3—Anxiety and stress about a new model of care: Engaged in the paradigm shift from traditional to group care (Active Participation stage).

Initially, the midwives were apprehensive about attempting the CP model of care. They described feeling stressed, discouraged at times, and anxious about their ability to facilitate the CP model, as illustrated in the following comments:

In the beginning, it created more work and the atmosphere was chaotic and stressful.

I fumbled through my first few groups and thought I didn’t give my best to my patients.

Only two patients showed up the first time when I expected eight. I had called everyone and expected more patients.

I was scared about leading the group and would have liked an apprenticeship. I feel like a beginner again and feel out of my comfort zone. And [I] don’t think I did a good job at facilitation.

After the first few CP sessions, however, the midwives felt more confident in conducting group sessions. They were genuinely impressed with their skills and with the responses of their patients, as reflected in the following statements:

It was somewhat freeing as I did not feel responsible for every question or concern.

Patients were really involved in their care, and I saw how the group process began to normalize as commonalities were shared.

It was a refreshing change of pace from individual visits.

Theme 4—Confidence and empowerment with the group: Actively engaged in new behavior (Action stage).

As the group sessions continued, the midwives truly began to understand the group process and their facilitation skills improved. The midwives’ confidence and empowerment with implementing the CP model of care is illustrated in the following comments:

The group is coming together and really nurturing themselves.

I am surprised at the level of personal sharing that goes on.

The energy and stability of the group is powerful.

I feel, at times, like I really do not have to be there.

Facilitation is getting better, and I feel that I am being less didactic.

I am learning to go with the flow.

This is not about me, it is about the group.

I still have some trouble with organization, as this model is so out-of-the-box.

Theme 5—Looking to the future: Committed to the CP model and wanting to sustain change (Maintenance stage).

After the last CP group sessions, the midwives expressed various positive perceptions regarding the whole experience of facilitating their first full CP group. For example, some of the midwives voiced the following statements:

I truly understand patient-centered care now, and I got to know my patients so much better in group than in individual care.

This was such a meaningful and positive experience for me, and I really had fun.

It met all my expectations, intentions, and more.

The midwives were very happy with the CP model of care and their satisfaction scores were 10/10. All of the midwives said that their facilitation skills improved throughout the course of the CP sessions and that they wanted to continue to improve their skills with the facilitation process. For example, some of the midwives said,

I have increased confidence in my facilitation skills, and I went from teaching to facilitation.

I was able to see the group bond and work together as my skills grew.

I am relaxing and letting the group happen.

I do need more experience with silence.

Looking forward to the future and to the sustainability of the CP model in their practices, the midwives expressed their commitment to the CP model of care, as evident in the following statements:

This is a great model for my population, and I want to increase patient access to CP.

I want to start a new group every month.

I want to include family members in the groups and figure out childcare.

It will be difficult for me to return to traditional care.

I am thinking about improvement.

I will do things differently the next time and I have learned from my mistakes.

Structurally, I will refine the process within the organization.

This is the midwifery model of care.

I can’t wait to start another group.

DISCUSSION

The findings from our study suggest that midwives who are given the opportunity for change in their practice are challenged by, and eventually satisfied with, the process of using the CP model of group patient-centered care. The midwives in our study seemed to feel a significant sense of accomplishment and empowerment with the process of facilitating and completing CP group sessions. The improved sense of providing safe, sensitive, and satisfying comprehensive prenatal care was fun and energizing for the midwives and for their support staff. The midwives also described how the CP model of group prenatal care was empowering and transformative not only to the patients but also to the midwives. The midwives’ initial intention for choosing the CP model, which was self-identified at CP educational trainings, was accomplished, and provider satisfaction with the CP model was evident in the findings from our study.

Implementing changes in the mode of health-care birth is difficult, especially when patients and providers have been entrenched in traditional approaches to prenatal care. Based on the findings from our study, the most profound challenges associated with implementing the CP model of group prenatal care are recruitment of patients, provider participation (including learning about and feeling comfortable with facilitation skills), adequate site funding, evaluation of the model, administrative support, and system redesign for the sustainability of the CP model.

Provider satisfaction and empowerment that are derived through the CP model of prenatal care are essential to overcoming the challenges of implementing CP and ensuring the sustainability of the CP model. Midwives’ satisfaction with the CP model will entice more midwives to consider adopting the CP model in their practice. For provider satisfaction, the motivation to redesign the practice setting could be accomplished through “opt-out” methods of recruitment. This system redesign occurs when CP is marketed to women and their families as the primary model of prenatal care, unless women clearly chose not to participate in group care.

Study Limitations

A major limitation of our study is the small sample size. However, repetitive themes clearly emerged from the six midwives’ input. Because our investigation is one of the first qualitative studies that examined midwives’ perceptions of implementing the CP model of group prenatal care, more research is warranted to ascertain and confirm the motivation, challenges, acceptance, and sustainability of CP’s important contribution to obstetrical health care and childbirth education.

Implications for Practice

Based on our study’s findings, we recommend that more individual providers and professional organizations embrace the CP model of group prenatal care and that more midwifery, nursing, and medical schools integrate CP into their obstetrical/maternity curricula. We also recommend further research to investigate why health-care educational programs currently do not include CP in their curricula. Incorporating the CP model into maternity care not only provides greater midwifery/provider satisfaction but also may assist families with increased knowledge and empowerment to better navigate the complicated health-care system.

The CP model combines the elements of prenatal care and childbirth education into one entity (Baldwin, 2006; Rising, 1998; Walker & Worrell, 2008). There are many similarities between the two approaches, but some would argue that CP alone does not replace childbirth education classes, especially for first-time parents (Walker & Worrell, 2008). Certainly, the goals of CP and childbirth education classes share common goals of increasing expectant parents’ knowledge of pregnancy, preparation for birth, and social support, as well as empowering women and promoting health (Walker & Worrell, 2008). CP may reach a more diverse population of women and families and, therefore, provide much needed preparation for birth combined with prenatal care for individuals who cannot or will not attend additional childbirth education classes. Many additional contact hours with midwives and other health-care providers during the CP group sessions compared with traditional exam room care provide evidence that CP produces more beneficial outcomes for mothers and their babies.

The goals of CenteringPregnancy and childbirth education classes share common goals of increasing expectant parents’ knowledge of pregnancy, preparation for birth, and social support, as well as empowering women and promoting health.

As we move forward toward effective health-care reform, it is necessary to understand models of prenatal care that motivate providers, provide outstanding health outcomes for both mother and baby, increase knowledge for mothers, and provide higher satisfaction for both midwives and clients. The CP model of group prenatal care certainly fits that mold and, as King (2009) stated, shows “great promise” for the future of prenatal care everywhere (p. 167).

Biography

KAREN BALDWIN is an associate professor of nursing and the coordinator of the graduate nurse practitioner program at Mount Saint Mary College in Newburgh, New York. In 2003, she completed her doctoral work in health education at Columbia University Teachers’ College in New York, with a dissertation on CenteringPregnancy. GAIL PHILLIPS has been a faculty member with The Centering Health Institute since 2003. As a certified nurse–midwife, she remains passionate about the innovative CenteringPregnancy model of prenatal care, which has empowered her clients, their families, and her practice.

REFERENCES

- Baldwin K. A. (2006). Comparison of selected outcomes of CenteringPregnancy versus traditional prenatal care. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 51(4), 266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T., & Grumbach K. (Eds.). (2007). Patient-centered care: Finding the balance In Improving primary care: Strategies and tools for a better practice (pp. 37–50). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. R., Obichere R., Knoll F., & Baruwa E. M. (2006). A study to compare productivity and cost of the CenteringPregnancy model of prenatal care with a traditional prenatal care model. Final Report to March of Dimes.

- Grady M. A., & Bloom K. C. (2004). Pregnancy outcomes of adolescents enrolled in a CenteringPregnancy program. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 49(5), 412–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics J. R., Kershaw T. S., Westdahl C., Magriples U., Massey Z., Reynolds H., & Rising S. S. (2007). Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 110(2Pt. 1), 330–339 doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics J. R., Kershaw T. S., Westdahl C., Rising S. S., Klima C., Reynolds H., & Magriples U. (2003). Group prenatal care and preterm birth weight: Results from a matched cohort study at public clinics. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 102(5Pt. 1), 1051–1057 doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(03)00765-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2010). Emerging content: Patient-centered care. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/PatientCentered

- Institute of Medicine (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy H. P., Farrell T., Paden R., Hill S., Jolivet R., Willetts J., & Rising S. S. (2009). “I wasn’t alone”—A study of group prenatal care in the military. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 54(3), 176–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King T. L. (2009). Prenatal care for the 21st century: Outside the 20th century box. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 54(3), 167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klima C., Norr K., Vonderheid S., & Handler A. (2009). Introduction of CenteringPregnancy in a public health clinic. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 54(1), 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick G. (2004). CenteringPregnancy and the current state of prenatal care. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 49(5), 405–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit D., & Beck C. T. (Eds.). (2009a). Analyzing qualitative data In Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (8th ed., pp. 507–535). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins [Google Scholar]

- Polit D., & Beck C. T. (Eds.). (2009b). Definition of phenomenology In Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (8th ed., pp. 761). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J. O., & DiClemente C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rising S. S. (1998). Centering pregnancy. An interdisciplinary model of empowerment. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery, 43(1), 46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rising S. S., Kennedy H. P., & Klima C. C. (2004). Redesigning prenatal care through CenteringPregnancy. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 49(5), 398–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson B., Aycock D. M., & Darnell L. A. (2009). Comparison of centering pregnancy to traditional care in Hispanic mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13(3), 407–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelton J., Mullins R., Langston L. T., Womack S., Ebersole J. L., Rising S. S., & Kovarik R. (2009). CenteringPregnancySmiles: Implementation of a small group prenatal care model with oral health. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 20(2), 545–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teate A., Leap N., Rising S. S., & Homer C. S. (2011). Women’s experiences of group antenatal care in Australia—The CenteringPregnancy pilot study. Midwifery, 27(2), 138–145 doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachtel T., & McCold P. (2001). Restorative justice in everyday life In Strang H. & Braithwaite J. (Eds.), Restorative justice and civil society (pp. 114–129). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. S., & Worrell R. (2008). Promoting healthy pregnancies through perinatal groups: A comparison of CenteringPregnancy® group prenatal care and childbirth education classes. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 17(1), 27–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westdahl C., Kershaw T. S., Rising S. S., & Ickovics J. R. (2008). ILCA abstracts—Group prenatal care improves breastfeeding initiation and duration: Results from a two-site randomized controlled trial. Journal of Human Lactation, 24(1), 94–110 [Google Scholar]