Abstract

There is increasing evidence that reactive oxygen species (ROS), a group of unstable and highly reactive chemical molecules, play a key role in regulating and maintaining life-history trade-offs. Upregulation of ROS in association with immune activation is costly because it may result in an imbalance between pro- and antioxidants and, hence, oxidative damage. Previous research aimed at quantifying this cost has mostly focused on changes in the pro-/antioxidant balance subsequent to an immune response. Here, we test the hypothesis that systemic ROS may constrain immune activation. We show that systemic, pre-challenge superoxide (SO) levels are negatively related to the strength of the subsequent immune response towards the mitogen phytohaemagglutinin in male, but not female painted dragon lizards (Ctenophorus pictus). We therefore suggest that systemic SO constrains immune activation in painted dragon males. We speculate that this may be due to sex-specific selection pressures on immune investment.

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, immunity, Ctenophorus pictus, phytohaemagglutinin

1. Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), a group of unstable and highly reactive chemical molecules, have recently become an important focus in evolutionary ecology research. There is increasing evidence that ROS are involved in physiological processes which link life-history traits, such as reproduction and ageing and, hence, play a key role in regulating and maintaining life-history trade-offs (e.g. [1,2] for comprehensive reviews).

While respiration, i.e. the reduction of molecular oxygen to form water by the electron transport chain in the mitochondria, is the major source of ROS production in aerobic organisms [3], ROS-producing enzymes and enzyme complexes involved in immune defence constitute other important sources of ROS production [1,2]. Among those, the NADPH oxidase enzyme complex, which is located in the membranes of professional phagocytes (e.g. macrophages) as well as B and T lymphocytes, is thought to play a major role in this type of ROS production [4]. Oxidative burst, the rapid production of high cellular ROS levels through NADPH oxidase, is an integrated part of the innate immune system with the function to kill invading bacteria and other microbes [4].

Although ROS fulfill important functions in cellular signalling (e.g. as modifiers of signalling pathways that control the proper development and proliferation of cells [5]) as well as in killing foreign pathogens (see above), overproduction of ROS can inflict oxidative damage on cell components. To minimize such cellular damage by ROS, aerobic organisms possess a sophisticated system of endogenous antioxidant defences, which scavenge unwanted ROS [4]. The depletion of antioxidant reserves by immune system generated ROS is thought to represent a significant cost of immune activation with potentially important fitness consequences (e.g. [6,7]).

However, the cost of immune activation in terms of immune-generated ROS is unlikely to depend solely on the availability of antioxidant defences. Here, we explore the possibility that systemic ROS levels may act as constraints for immune function. Studies to date have mainly considered changes in the pro-/antioxidant balance subsequent to an immune challenge (e.g. [7] and references therein). However, because immune activation is associated with an increase in ROS levels, we hypothesize that individuals with high inherent ROS profiles may be limited in their capacity to mount an immune response as they may be more prone to the risk of oxidative damage. We tested this hypothesis in wild-caught painted dragon lizards (Ctenophorus pictus) by measuring cellular ROS levels and relating them to the subsequent immune response to the mitogen phytohaemagglutinin-A (PHA). We predicted that if systemic ROS levels compromise immune function then the strength of the immune response should be negatively related to ROS levels.

2. Material and methods

(a). Animal husbandry

The lizards were caught at Yathong Nature Reserve, New South Wales (145°35′; 32°35′) at the beginning of the mating season (September 2008) and brought back to holding facilities at Wollongong University. All lizards were kept individually in cages (60 × 60 × 50 cm), on a 12 L : 12 D regime, with a spotlight at one end of the cage to allow thermoregulation to the preferred body temperature and fed crickets and meal worms every second day. The experiment as described below was conducted after one month in captivity. Sample sizes were n = 20 for males and n = 25 for females.

(b). Quantifying reactive oxygen species levels

All lizards were blood-sampled prior to immunization with PHA (see below). Blood was collected with a glass capillary from vena angularis (in the corner of the mouth). Systemic ROS levels were quantified according to previously specified protocols [8]. Briefly, we used flow cytometry in combination with two probes (MitoSOX Red (MR) and dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR), Invitrogen) that freely diffuse into cells, accumulate within the mitochondria and become fluorescent when oxidized by specific ROS (MR measures specifically superoxide (SO); DHR identifies various ROS species, including singlet oxygen, SO, H2O2 and peroxynitrite, hereafter, referred to as ‘unspecific ROS’). Details of flow cytometry methods are included in the electronic supplementary material.

(c). Phytohaemagglutinin challenge

To assess whether circulating ROS levels constrain immunity, we used a PHA assay. After blood-sampling, lizards were injected with 30 µg PHA (Sigma L-8754) dissolved in 30 µl sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) into the left hindfoot pad. PHA injection produces local inflammation and swelling and can therefore be used a simple immune measure to assess an individuals' ability to mount an inflammatory response [9]. The same volume of PBS only was injected into the right hindfoot pad as a control. The thickness of each foot pad was measured three times to the nearest 0.01 mm with digital calipers immediately before and 24 h (±0.5) after injection. The mean of the three measures was used in analyses. The strength of the immune response was assessed as the difference in swelling between the PHA-injected and the control foot pads. Concomitant with the measures of foot pad thickness, lizards were weighed to the nearest 0.01 g and their snout–vent–length (SVL) measured to the nearest 0.5 mm.

(d). Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in SAS System v. 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We used general linear models (PROC GLM) with immune response or body mass change as dependent variable, sex as a fixed factor, and ROS levels (basal SO (bSO) and unspecific ROS) and SVL as covariates. SVL was included in the analysis because painted dragons are sexually dimorphic (with males being larger than females) and because SVL is a proxy of age (being ectotherms, painted dragons grow throughout life). Two-way interactions between factors and covariates were initially included in the models, but removed at α > 0.25 [10]. Residuals of the models were tested for normality. All tests were two-tailed with a significance level set at α < 0.05.

3. Results

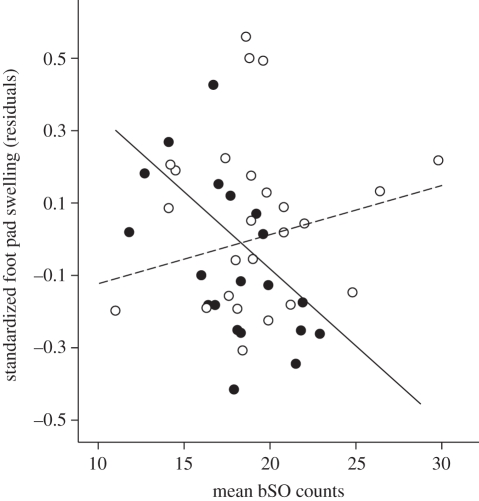

There was no sex difference in bSO or unspecific ROS levels (p > 0.25). bSO levels were negatively related to SVL (F1,43 = 5.21, p = 0.028), but not those for unspecific ROS (F1,43 = 0.10, p = 0.76). Males had on average lower immune responses than females (least-squares means; 0.27 ± 0.06 mm versus 0.57 ± 0.05 mm, (mean ± s.e.)) and larger individuals mounted stronger immune responses than smaller ones (table 1). The strength of the PHA response was significantly predicted by bSO levels at the time of immunization, but in a sex-dependent manner (sex by bSO interaction; table 1). The strength of the immune response was negatively related to bSO levels in males, but not in females (figure 1). Unspecific ROS were not related to the strength of the immune response (p > 0.39 for main effect and its interaction with sex).

Table 1.

Effects of sex, body size (snout–vent–length = SVL) and basal superoxide (bSO) on PHA-induced swelling in the hindfoot of painted dragon lizards (see §2 for details).

| source | d.f. | SS | MS | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| response variable: PHA-induced swelling (model F4,40 = 4.53, p = 0.004, r2 = 0.31) | |||||

| sex | 1 | 0.233746 | 0.233746 | 5.45 | 0.025 |

| bSO | 1 | 0.076642 | 0.076642 | 1.79 | 0.189 |

| bSO × sex | 1 | 0.391690 | 0.391690 | 9.14 | 0.004 |

| SVL | 1 | 0.460213 | 0.460213 | 10.74 | 0.002 |

Figure 1.

Scattergram illustrating the significant interaction term between sex and basal superoxide (bSO) levels for the immune response towards PHA (standardized for body size; residuals from a foot pad swelling—SVL regression). Males, filled circles and solid line (n = 20; b: −0.043 ± 0.014; F1,18 = 9.10, p = 0.007); females, open circles and dashed line (n = 25; b: 0.014 ± 0.012; F1,23 = 1.37, p = 0.25).

Body mass change within 24 h after PHA injection was not affected by bSO or unspecific ROS levels (p > 0.25 for main effects and interactions with sex). Sex also did not affect body mass change (F1,41 = 0.24, p = 0.63). Moreover, body mass change was not related to the strength of the immune response (body mass change: F1,36 = 1.36, p = 0.25; body mass change by sex interaction: F1,41 = 0.05, p = 0.82). There was, however, a significant negative relationship between SVL and change in body mass (b: –0.02 ± 0.01, F1,43 = 4.09, p = 0.049). Larger individuals lost weight 24 h post immunization whereas smaller ones gained weight.

4. Discussion

As predicted, we found a negative relationship between systemic ROS levels and the strength of the immune response. The relationship was specific to bSO, but not unspecific ROS and was restricted to males only. We have previously shown that bSO levels, but not unspecific ROS levels, are heritable [11] suggesting that individual variation in lizard SO levels may be less plastic in response to environmental variation. This is corroborated by a previous study in which we show that bSO, but not unspecific ROS, are negatively correlated with colour change in male painted dragons [9]. Furthermore, our results are in line with recent studies on mutant mice which exhibit reduced/elevated mitochondrial SO production and associated enhancement/impairment of immune function [12,13].

Why was the negative relationship between SO and immunity restricted to males? Female painted dragons showed on average a stronger immune response towards PHA than males, which is consistent with higher female immuno-competence in many vertebrate species (e.g. [14] for a recent review). Bateman's principle predicts that males maximize fitness through an increase in mating rate whereas females maximize fitness through investment in longevity [15], and therefore, selection should favour enhanced immunity in females [16]. Moreover, a recent study on tarantula spiders (Brachypelma albipilosa) suggests that sex-specific differences in longevity are associated with differences in several ROS parameters, one of them being mitochondrial SO production [17]. Male and female painted dragons differ in many behavioural and reproductive characteristics. Males engage in overt aggressive behaviour with rising testosterone levels and open exposure to rivals and predators during territory patrolling and mate acquisition throughout the day [18,19]. Females have a more cryptic lifestyle and spend considerable time basking to maintain appropriate incubation conditions for developing follicles and eggs [19]. These differences are likely to be reflected in physiological parameters. SO production is linked to metabolic rate and, hence, energetic requirements. It is possible that the negative relationship between bSO and immune responses in males reflects sex-specific energy requirements. However, if the relationship were purely dependent on energetic demands then a negative relationship between the change in body mass and the immune response might be expected. Alternatively, we suggest that different sources of ROS production (i.e. respiration and ‘ROS-producing’ enzyme complexes involved in immune activation) may negatively affect each other and that males with higher systemic SO levels mount smaller immune responses because they may be limited in their ability to mobilize antioxidant defences in response to the immune activation. In accordance with Bateman's principle, we speculate that higher immune responses in painted dragon females, and the lack of a negative relationship between ROS and the strength of the immune response, in particular, may be owing to sex-specific selection pressures on immune investment.

Acknowledgements

This research was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee, Wollongong University (permit no. AE04/03-05).

We thank E. Snaith and G. Snaith for logistic support and the Australian Research Council (M.O.), the Lars Hierta Memorial Foundation (M.T.), the Helge Ax:son Johnsons Foundation (M.T.) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (PBSKA-119056, M.T.) for funding support. Three anonymous reviewers provided constructive criticism on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Dowling D. K., Simmons L. W. 2009. Reactive oxygen species as universal constraints in life-history evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 1737–1745 10.1098/rspb.2008.1791 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1791) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monaghan P., Metcalfe B., Torres R. 2009. Oxidative stress as a mediator of life history trade-offs: mechanisms, measurements and interpretation. Ecol. Lett. 12, 75–92 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01258.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01258.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barja G. 2007. Mitochondrial oxygen consumption and reactive oxygen species production are independently modulated: implications for aging studies. Rejuvenation Res. 10, 215–223 10.1089/rej.2006.0516 (doi:10.1089/rej.2006.0516) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. 2007. Free radicals in biology and medicine. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartosz G. 2009. Reactive oxygen species: destroyers or messengers? Biochem. Pharmacol. 77, 1303–1315 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.11.009 (doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2008.11.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres R., Velando A. 2007. Male reproductive senescence: the price of immune-induced oxidative damage on sexual attractiveness in the blue-footed booby. J. Anim. Ecol. 76, 1161–1168 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01282.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01282.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costantini D., Moller A. P. 2009. Does immune response cause oxidative stress in birds? A meta-analysis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 153, 339–344 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.03.010 (doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.03.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsson M., Wilson M., Isaksson C., Uller T., Mott B. 2008. Carotenoid intake does not mediate a relationship between reactive oxygen species and bright colouration: experimental test in a lizard. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 1257–1261 10.1242/jeb.015065 (doi:10.1242/jeb.015065) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinkler M., Bainová H., Albrecht T. 2010. Functional analysis of the skin-swelling response to phytohaemagglutinin. Func. Ecol. 24, 1081–1086 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01711.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01711.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinn G. P., Keough M. J. 2002. Experimental design and data analysis for biologists. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsson M., Wilson M., Uller T., Mott B., Isaksson C., Healey M., Wanger T. 2008. Free radicals run in lizard families. Biol. Lett. 4, 186–188 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0611 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0611) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang D., Malo D., Hekimi S. 2010. Elevated mitochondrial oxygen species generation affects the immune response via hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in long-lived Mclk1+/− mouse mutants. J. Immunol. 184, 582–590 10.4049/jimmunol.0902352 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0902352) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Case A. J., McGill J. L., Tygrett L. T., Shirasawa T., Spitz D. R., Waldschmidt T. J., Legge K. L., Domann F. E. 2011. Elevated mitochondrial superoxide disrupts normal T cell development, impairing adaptive immune responses to an influenza challenge. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 50, 448–458 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.11.025 (doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.11.025) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nunn C. L., Lindenfors P., Pursall E. R., Rolff J. 2009. On sexual dimorphism in immune function. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 61–69 10.1098/rstb.2008.0148 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0148) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bateman A. J. 1948. Intra-sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity 2, 349–368 10.1038/hdy.1948.21 (doi:10.1038/hdy.1948.21) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rolff J. 2002. Bateman's principle and immunity. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 867–872 10.1098/rspb.2002.1959 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1959) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Criscuolo F., Font-Sala C., Bouillaud F., Poulin N., Trabalon M. 2010. Increased ROS production: a component of the longevity equation in the male mygalomorph, Brachypelma albopilosa. PLoS ONE 5, e13104. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013104 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsson M., Healey M., Astheimer L. B. 2007. Afternoon T: testosterone level is higher in red than yellow male polychromatic lizards. Physiol. Behav. 91, 531–534 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.025 (doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsson M., Healey M., Wapstra E., Schwartz T., Lebas N., Uller T. 2008. Mating system variation and morph fluctuations in a polymorphic lizard. Mol. Ecol. 16, 5307–5317 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03578.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03578.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]