Abstract

The plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Plague bacteria are thought to inject effector Yop proteins into host cells via the type III pathway. The identity of the host cells targeted for injection during plague infection is unknown. We found, using Yop β-lactamase hybrids and fluorescent staining of live cells from plague-infected animals, that Y. pestis selected immune cells for injection. In vivo, dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils were injected most frequently, whereas B and T lymphocytes were rarely selected. Thus, it appears that Y. pestis disables these cell populations to annihilate host immune responses during plague.

Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague or black death, harbors a virulence plasmid that encodes a type III secretion machine and its Yop protein substrates (1, 2). The essential contribution of type III secretion to the pathogenesis of plague was revealed by comparing lethal infectious doses of wild-type and mutant strains (3). Yersinia type III injection of Yop proteins into tissue culture cells has been detected with fluorescent microscopy, adenylate cyclase or Elk tag fusions, and fractionation techniques (4–7). These technologies, however, have not been useful for measuring the selection of host cells as targets of type III injection during infection.

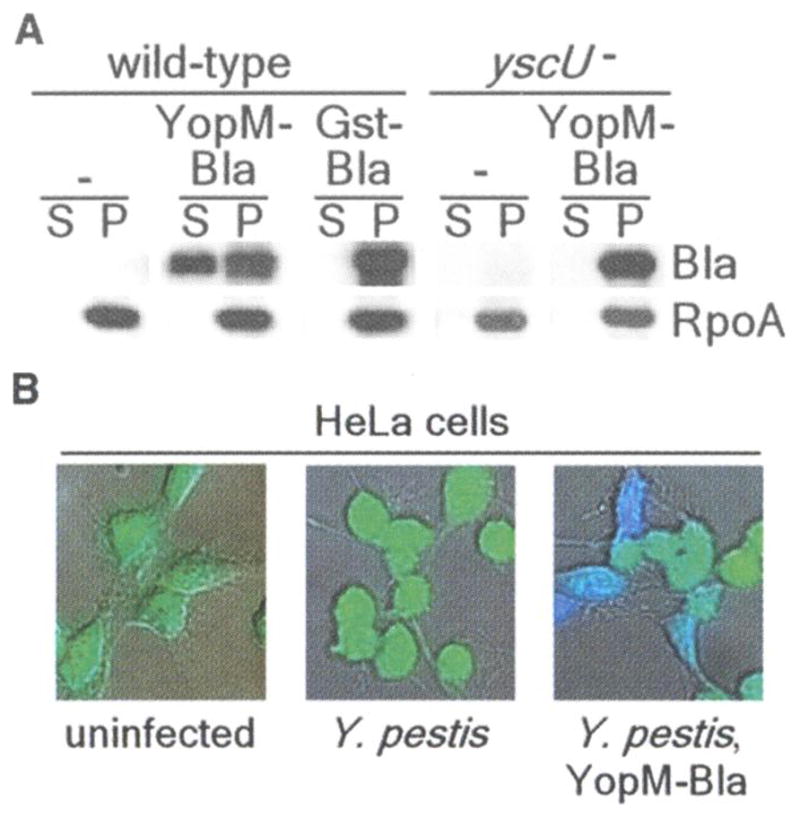

CCF2-AM, a β-lactamase substrate, has been used to detect bacterial type HI reporter injection into tissue culture cells(8). CCF2-AM is a membrane-permeant ester with two fluorophores attached to cephalosporin that exhibit fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). Excitation of coumarin (409 nm) results in green fluorescence emission from fluorescein (520 nm) in intact CCF2-AM (9). β-Lactamase cleaves CCF2-AM, thereby disrupting FRET and establishing blue fluorescence emission. To investigate the usefulness of β-lactamase as a reporter for in vivo target cell selection by Y. pestis, we transformed plasmids carrying translational fusions between YopM or glutathione S-transferase (GST) and the mature domain of TEM-1 β-lactamase (YopM-Bla and GST-Bla, respectively) into Y. pestis strain KIM D27(10) Bacterial cultures were induced for type III secretion via the depletion of calcium at 37°C and then centrifuged to separate the extracellular medium from bacterial cells (11). Immunoblotting of cell-associated and secreted proteins identified YopM-Bla in the extracellular medium of KIM D27 cultures (Fig. 1A). In contrast, GST-Bla or RpoA, the α subunit of RNA polymerase, were not secreted. Disruption of yscU, which encodes a secretion machine component, abrogates all type III secretion (12). Reporter plasmids transformed into Y. pestis strain CHI30, carrying a stable insertion of MuAphP1 in yscU, revealed YopM-Bla only in bacterial cells (Fig. 1A) (13). Infection of tissue cultures with Y. pestis KIM D27 did not affect CCF2-AM-mediated green fluorescence, even though the HeLa cells rounded after 2 to 3 hours of infection as a result of the injection of Yop effectors (Fig. IB). After infection of tissue culture cells with Y. pestis KIM D27 (pMM83, expressing YopM-Bla), cells fluoresced blue, revealing cleavage of the CCF2-AM cephalosporin moiety by the hybrid (β-lactamase (Fig. IB). GST-Bla was not injected into HeLa cells, as tissue cultures infected with KIM D27 (pMM91, expressing GST-Bla) generated only green fluorescence. YopM-Bla was not injected and blue fluorescence was not observed for HeLa cells infected with yscU, yopD, or lcrV mutants, because each of the disrupted genes is required for type III injection (fig. S1) (14–16). Thus, TEM-1 β-lactamase serves as a reporter for transport of hybrids by the Y. pestis type III secretion system.

Fig. 1.

(A) Y. pestis secretes YopM-Bla, but not GST-Bla, into the medium in a type III machinery (yscU)-dependent manner during in vitro secretion assays. Cultures were separated into supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions, and proteins were visualized by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and immunoblotting with antisera to β-lactamase (Bla) and RNA polymerase A (RpoA). (B) HeLa cells were infected with Y. pestis carrying either empty vector (center) or YopM-Bla (right), followed by staining with CCF2-AM and visualization of live cells by fluorescence microscopy. Blue and green fluorescence and differential interference contrast images were overlaid to obtain composite images.

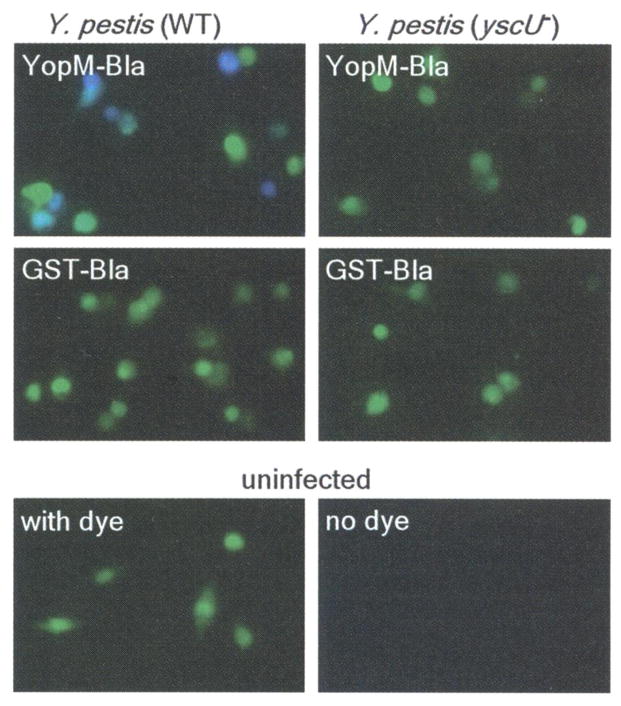

To measure type III injection of primary cells, we isolated macrophages from the peritoneal cavity of mice, infected them with Y. pestis, and stained them with CCF2-AM. Infections with KIM D27 strains carrying pMM83 (YopM-Bla), but not pMM91 (GST-Bla), caused blue fluorescence of CCF2-AM-stained cells (Fig. 2). As observed with HeLa cells, blue fluorescence required functional yscU (Fig. 2) as well as lcrV and yopD. Thus, YopM-Bla and CCF2-AM staining can be used to measure selection of murine target cells by the Yersinia type III secretion system.

Fig. 2.

Type III injection of peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages were harvested from C57BL/6 mice and infected with Y. pestis strains (wild type or yscU−) carrying either YopM-Bla or GST-Bla. Live cells were stained with CCF2-AM and visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

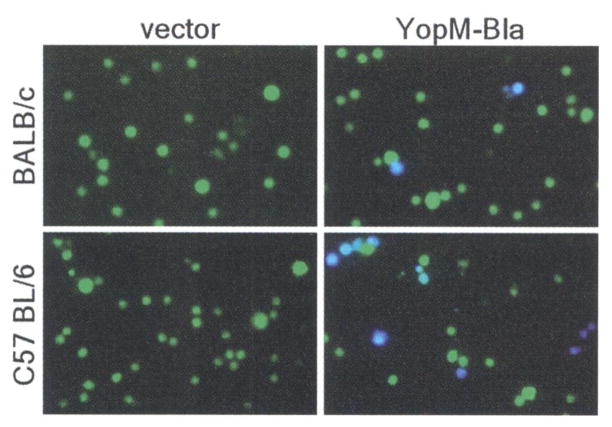

Y. pestis replicates within lymphoid tissues of experimental animals—that is, in the lymph nodes, bone marrow, liver, and spleen (17, 18). These organs are quickly filled with plague bacilli and are depleted of immune cells; they then undergo tissue necrosis, and the death of the infected animal follows (19). To test whether type III injection can be detected during plague infection, we infected mice intravenously with Y. pestis KIM D27 (pMM83) or Y pestis KIM D27 (pHSG576, the vector control). All infections caused lethal plague disease within 4 days. At 2 days after infection, moribund mice were killed and spleens were removed. The tissue was homogenized, and cells were stained with CCF2-AM and viewed by fluorescence microscopy. Blue and green cells were present in spleens of BALB/c or C75BL/6 mice infected with KIM D27 (pMM83), whereas splenocytes from mice infected with KIM D27 (pHSG576) stained homogeneously green (Fig. 3). Both plasmids were stably maintained during infection and did not affect virulence (13).

Fig. 3.

Mice were infected with 105 CFU (BALB/c) or 103 CFU (C57BL/6) of Y. pestis carrying either pHSG576 (vector) or pMM83 (YopM-Bla). After 2 days, infected spleens were removed, homogenized, and incubated with CCF2-AM; live cells were observed by fluorescence microscopy.

We sought to determine the identity of cells targeted by the Yersinia type III pathway. Spleens of naïve C57BL/6 mice were homogenized and infected with Y. pestis KIM D27 carrying pMM83 (YopM-Bla), pMM85 (YopE-Bla), or pHSG576. After 3 hours, cells were stained with CCF2-AM and viewed by fluorescence microscopy. Some cells (e.g., erythrocytes) were not stained with CCF2-AM and displayed no fluorescence. However, most splenocytes, either uninfected or infected with KIM D27 (pHSG576), fluoresced green. Splenocytes infected with plague strains KIM D27 (pMM83) and KIM D27 (pMM85) generated uniform blue fluorescence, signifying that these splenocytes had been injected with YopM-Bla or YopE-Bla (fig. S2). Y pestis type III injection of splenocytes was not affected by treatment with cytochalasin D, which indicates that extracellular, but not phagocytosed, microbes generate blue fluorescent signals (fig. S3). To determine whether Y. pestis selected specific immune cells in vitro for type III injection, we isolated splenocytes and infected individual cell populations with Y. pestis strains KIM D27 carrying pMM83, pMM85, or pHSG576; some splenocytes were left uninfected. Y. pestis injected B cells, CD4+ T helper cells, CD8+ T killer cells, dendritic cells, or macrophages with YopM-Bla and YopE-Bla but not with GST-Bla (fig. S4).

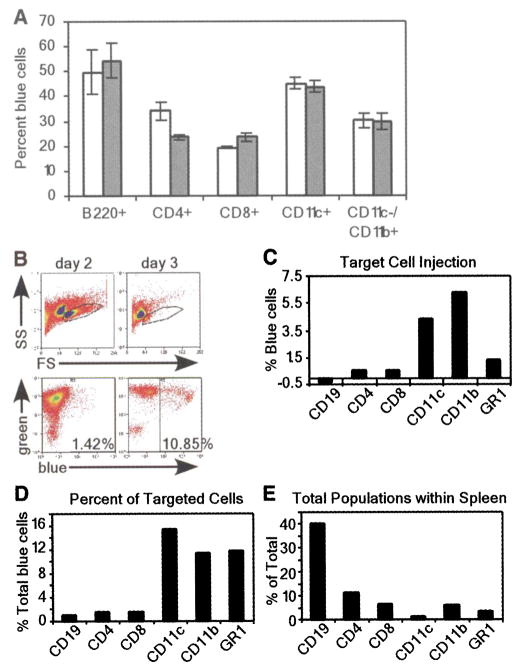

To quantify injected cells, we analyzed CCF2-AM-stained cell populations by flow cytometry for the percentage of blue fluorescent cells. Y. pestis injected all five cell types with YopM-Bla or YopE-Bla (Fig. 4A). After in vitro infection, injection of YopM-Bla and YopE-Bla occurred more frequently in B cells and dendritic cells, whereas CD8+ T cells and macrophages were injected less frequently. Surprisingly, YopM-Bla was injected more frequently than YopE-Bla into CD4+ T cells, whereas all other cell types were injected with both type III effectors at similar rates. Thus, there appear to be differences in the in vitro selection of immune cells for type III injection by Y. pestis, and not all effectors may be injected with similar efficiency into specific cell types.

Fig. 4.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of in vitro infections of purified cell populations with Y. pestis carrying pMM83 (YopM-Bla, white bars) or pMM85 (YopE-Bla, gray bars). The percentage of live blue cells for each cell type was plotted (data are means ± SEM of triplicate samples). (B) Mice were infected with 103 CFU of Y pestis carrying either pHSG576 (vector) or pMM83 (YopM-Bla). Splenocytes were harvested and stained with CCF2-AM as well as cell-specific surface markers. The R1 gate was set by forward scatter (FS) versus side scatter (SS) and exclusion of propidium iodide–positive cells (top panel). R1-gated cells were analyzed for blue and green fluorescence (bottom panel). (C) APC-conjugated antibodies to cell-specific markers were used to determine percentages of blue cells for each population. (D) The percentage of each cell type in the total population of blue cells was determined by gating on each cell-specific marker. (E) Total population of each cell type in infected spleens.

Although Y. pestis displays a preference for B cells and dendritic cells in vitro, true target cell selection cannot be measured under these conditions because microbes are not presented with a choice between different host cells. To address this problem, we examined target cell selection in vivo by infecting C57BL/6 mice with 103 colony-forming units (CFU) of Y. pestis strain KIM D27 carrying pMM83 or pHSG576. Moribund animals were killed 2 or 3 days after infection; spleens were removed, homogenized, and then stained with CCF2-AM. Stained splenocytes were subjected to flow cytometry, revealing a precipitous decline in live cells on the third day after infection (Fig. 4B). The number of KIM D27 (pMM83)-injected blue cells increased from 1.42% on day 2 to 10.85% on day 3. In contrast, KIM D27 (pHSG576) infection generated only background staining of blue cells (0.80% and 1.76% on days 2 and 3, respectively). The 10-fold increase in blue cells between days 2 and 3 can be accounted for by an increase in bacterial load as well as a decrease in immune cells from the spleen (20).

To further analyze target cell injection, we labeled splenocytes with allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated antibodies specific for CD19+/CD11c− (B cells), CD4+ (T helper cells), CD8+ (T killer cells), GR-1+ (granulocytes/ neutrophils), and CD11c+/CD11b− (dendritic cells) as well as CD11b+/CD11c− (macrophages), and we quantified the number of cells positive for both the antibody and blue fluorescence (Fig. 4C). At 2 days after infection, significant amounts of macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils fluoresced blue, indicating that these cells had been injected by Y. pestis with YopM-Bla. However, no significant type III injection was observed for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells or B cells (CD19+). When compared with the total amount of YopM-Bla-injected (blue) cells, target selection occurred most frequently for dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils, whereas B and T cells were not selected for type III injection (Fig. 4D). Blue staining of phagocytic cells during infection with Y. pestis KIM D27 (pMM83, expressing YopM-Bla) is most likely due to type III injection and not caused by phagocytosis of β-lactamase containing bacteria, because control infections with Y pestis KIM D27 (pMM91, expressing Gst-Bla) resulted only in background fluorescence of splenocytes (fig. S5). To obtain additional proof for this hypothesis, future studies will need to test its predictions on multiple levels of experimental specificity. Because of the marked decline in live cells isolated 3 days after infection, it was not possible to make a statistically valid analysis of type III–injected cell types. However, it seemed that the percentage of blue cells was similar for all cell types, which suggests that all immune cells eventually became injected. Because B cells and T cells—which constitute the overwhelming majority of splenic immune cells (Fig. 4E)—were not injected on day 2, selection mechanisms must exist for bacterial type III injection of target cells. Macrophages, dendritic cells, and granulocytes/ neutrophils are early targets for injection. Thus, Y. pestis appears to make use of the type III secretion system to destroy cells with innate immune functions that represent the first line of defense, thereby preventing adaptive responses and precipitating the fatal outcome of plague.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Bindokas for assistance with fluorescence microscopy, J. Marvin for help with flow cytometry, W. Williams and N. Green for isolating primary immune cells, Z. Haga for the statistical analysis, and M. Casadaban for providing strains. We acknowledge membership in and support from the Great Lakes Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Consortium (GLRCE) (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases award 1-U54-AI-057153).

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Cornelis GR, et al. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1315. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1315-1352.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornelis GR. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry RD, Harmon PA, Bowmer WS, Straley SC. Infect Immun. 1986;54:428. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.2.428-434.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosqvist R, Magnusson KE, Wolf-Watz H. EMBO J. 1994;13:964. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sory MP, Boland A, Lambermont I, Cornelis GR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.11998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day JB, Ferracci F, Plano GV. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:807. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee VT, Anderson DM, Schneewind O. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:593. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charpentier X, Oswald E. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5486. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5486-5495.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zlokarnik G, et al. Science. 1998;279:84. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brubaker RR. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:1404. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.3.1404-1406.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng LW, Anderson DM, Schneewind O. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:757. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3831750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allaoui A, Woestyn S, Sluiters C, Cornelis G. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4534. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4534-4542.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.See supporting data on Science Online.

- 14.Håkansson S, Bergman T, Vanooteghem JC, Cornelis G, Wolf-Watz H. Infect Immun. 1993;61:71. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.71-80.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Håkansson S, et al. EMBO J. 1996;15:5812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee VT, Tarn C, Schneewind O. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Une T, Brubaker RR. J Immunol. 1984;133:2226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson GW, Jr, et al. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4580. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4580-4585.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sebbane F, Gardner D, Long D, Gowen BB, Hinnebusch BJ. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1427. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62360-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philipovskiy AV, et al. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1532. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1532-1542.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.