Abstract

Objective

To compare the effects of essential vs. long chain omega (n)-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Materials/Methods

In this 6-week, prospective, double-blinded, placebo (soybean oil) controlled study, 51 completers received 3.5 g n-3 PUFA/day (essential from flaxseed oil or long chain from fish oil). Anthropometric variables, cardiovascular risk factors and androgens were measured; oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and frequently sampled intravenous GTT (FSIVGTT) were conducted at the baseline and 6 wks.

Results

Between group comparisons showed significant differences in serum triglyceride response (p = 0.0368), while the changes in disposition index (DI) also tended to differ (p = 0.0621). When within group changes (after vs. before intervention) were considered, fish oil and flaxseed oil lowered serum triglyceride (p = 0.0154 and p = 0.0176, respectively). Fish oil increased glucose at 120 min of OGTT (p = 0.0355); decreased Matsuda index (p= 0.0378); and tended to decrease early insulin response during IVGTT (AIRg; p = 0.0871). Soybean oil increased glucose at 30 min (p = 0.0030) and 60 min (p = 0.0121) and AUC for glucose (p = 0.0122) during OGTT; tended to decrease AIRg during IVGTT (p= 0.0848); reduced testosterone (p = 0.0216) and tended to reduce SHBG (p = 0.0858). Fasting glucose, insulin, adiponectin, leptin or hs-CRP did not change with any intervention.

Conclusions

Long chain vs. essential n-3 PUFA rich oils have distinct metabolic and endocrine effects in PCOS, and therefore they should not be used inter-changeably.

Keywords: Omega-3 fatty acids, polycystic ovary syndrome, insulin resistance

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disease of women in reproductive age. Depending on the ethnic background, one out of ten to sixteen women has PCOS. Disorders related to PCOS can be divided into two categories: reproductive and metabolic. The former includes anovulation, oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea, infertility; and androgen excess manifesting as hirsutism. The latter consists of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and obesity 1. Although inflammation is increased, this seems to relate to obesity, but not directly to PCOS 2. Insulin resistance leads to compensatory increase in circulating insulin (hyperinsulinemia) which in turn stimulates androgen production and contributes to ovarian dysfunction 3. As a testament to the importance of insulin resistance in ovarian dysfunction, treatment of insulin resistance and obesity increases ovulation and improves fertility in PCOS 4.

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA) improve several disorders associated with PCOS. Experimental and clinical research have indicated that n-3 PUFA increase insulin sensitivity, reduce hyperinsulinemia, lower plasma triglyceride and liver fat, decrease inflammation and possibly obesity 5–7. Therefore, PCOS patients are frequently advised to increase n-3 PUFA intake. However, there is an important knowledge gap in this field. Differences between the effects of essential n-3 PUFA (alpha linolenic acid, ALA) vs. long chain n-3 PUFA (eicosapentanoic acid, EPA, and docosahexanoic acid DHA) have not been distinguished. Thus patients and health care providers often use flaxseed oil (a rich source of the essential n-3 PUFA ALA) and fish oil (a rich source of the long chain n-3 PUFA EPA and DHA) inter-changeably. This may not be appropriate because in vivo conversion of the essential to the long chain n-3 PUFA is very inefficient in humans 8. In addition, essential and long chain n-3 PUFA act on different metabolic steps: ALA competes with the essential n-6 PUFA linoleic acid (LA;18:2 n-6) at the Δ6 desaturase enzyme—the rate limiting step for production of long chain PUFA, and inhibits conversion of LA to arachidonic acid (AA; 22:4 n-6) 9. On the other hand, the long chain n-3 PUFA (EPA and DHA) compete directly with AA on the lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase enzymes that regulate production of leukotrienes and prostaglandins, respectively 9.

This study compared the effects of equal amounts of the essential n-3 PUFA (ALA) from flaxseed oil vs. the long chain n-3 PUFA (EPA plus DHA) from the fish oil on anthropometric measures, glucose homeostasis, cardiovascular risk factors and androgen levels in women with PCOS. Soybean oil which is rich in n-6 PUFA linoleic acid was used as the control oil.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Subjects

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of California, Davis and registered with the NIH. The investigators did not have any conflict of interest.

Women between the ages 20–45 y and with a body mass index (BMI) of 25–45 kg/m2 who fulfilled the NIH criteria for PCOS 10 by having ovarian dysfunction, as evidenced by amenorrhea (no periods for >6 mo) or oligomenorrhea (<6 periods/y), clinical (hirsutism) or laboratory evidence for hyperandrogenemia (total testosterone >54 ng/dl or free testosterone >9.2 pg/ml), along with the absence of any confounding clinical pathology (i.e. Cushing’s disease, 21 hydroxylase deficiency or prolactinoma) were recruited. Patients were excluded if they used oral contraceptives, anti-androgenic medications, insulin sensitizers, d-chiro inositol, or any other medications or supplements that affect weight or insulin sensitivity during the preceding two months; had diabetes mellitus, untreated hypothyroidism or thyroid disease, and any other systemic illness such as renal, hepatic, and gastrointestinal disease; smoke; or drink > 2 alcoholic drinks per week.

Consort statement

Two hundred and twenty-six PCOS patients were assessed for eligibility; 159 subjects either failed to meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria (n=96), refused to participate (n=41) and had other reasons that prevented participation (n=22). Remaining 67 patients were allocated to randomization. Five subjects left after the baseline studies, before receiving the interventions; the remaining patients received either fish oil (n = 21), soybean oil (n=18) or flaxseed oil (n=23). Fifty-one patients (17 in each intervention) completed the 6-week study. The ethnic distribution of the completers was: 35 White, 5 African American, 5 Hispanic, 4 Asian, 1 American Indian and 1 Other.

Study design

Fatty acid compositions of the supplements are shown in Table 1. The goal was to supplement approximately 3.5 g of total n-3 PUFA daily. This was accomplished by providing six capsules of each supplement. Each capsule of flaxseed oil contained 545 mg ALA (Barleans Organic Oils, Ferndale, WA) and each capsule of fish oil contained 358 mg EPA plus 242 mg DHA (Nordic Naturals, Watsonville, CA). Soybean oil (Nordic Naturals, Watsonville, CA) was selected as placebo based on the recommendations of the Product Quality Working Group (PQWG) of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Each capsule of soybean oil contained 200 mg of oleic acid, 429 mg of LA acid 57 mg ALA and very small amounts of palmitic and stearic acids. Based on the nutrition intake data obtained in our previous PCOS study 11, flaxseed supplementation was expected to increase ALA intake by approximately 3-folds and fish oil supplementation was expected to increase EPA plus DHA intake by 20 folds. Six weeks of study duration was elected because this length of time is adequate to observe the effects of dietary fatty acids on plasma lipids and glucose homeostasis 12.

Table 1.

Fatty acid composition (%weight) of the supplements

| Fish oil | Flaxseed oil | Soybean oil | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated fats | |||

| Palmitic acid (16:0) | 5.0 | 5.7 | 9.7 |

| Stearic acid (18:0) | 2.1 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| Monounsaturated fats | |||

| Oleic acid (18:1, n-9) | 4.6 | 19.2 | 20.2 |

| Polyunsaturated fats | |||

| Linoleic acid (18:2, n-6) | 0.8 | 16.2 | 42.9 |

| Linolenic acid (18:3, n-3) | 0.6 | 54.5 | 5.7 |

| Eicosapentanoic acid (20:5, n-3) | 39.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Docosahexanoic acid (22:6, n-3) | 27.5 | 0 | 0.1 |

Data collection

Data were obtained at the beginning and at the end of the study at the Clinical and Translational Science Center Clinical Research Center of the University of California, Davis (CCRC). Menstruating women were tested during the follicular phase of the cycle. The OGTT and FS-IVGTT were performed one week apart.

Nutrition data

7-day food records were obtained at the beginning and at the end of the study and were analyzed by the CCRC dietitian using the Food Processor software (esha Research, Salem, OR).

Anthropometric data

Weight was measured in light clothing using the Tanita BWB800-P Digital Medical Scale. Body composition was determined using bioelectrical impedance 13.

OGTT

After an overnight fast, baseline samples were obtained; participants drank 75 g of glucose (Glucola™) and additional blood samples were obtained every 30 min for 2 hours.

FS-IVGTT

Participants were tested between 0600 and 0900, after an overnight fast. An intravenous catheter was placed in their forearm and kept open with normal saline. Heating pads were used in order to maximize blood flow. Three blood samples were obtained at times -15, -10 and -5 minutes. Glucose (0.3u/kg as 25% dextrose) was given intravenously at time 0 min. Intravenous insulin 0.03 u/kg (Humulin Regular: Eli Lilly) was given at time 20 min after the glucose administration. Blood samples were obtained at times 0, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8,10, 12, 14, 16, 19, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 90, 100, 120, 140, 160 and 180 min. Acute insulin response to glucose (AIRGlucose: an index of insulin secretion), β-cell function, sensitivity index (SI) and disposition index (DI) were calculated using MiniMod Millennium software (Dr. Bergman, Los Angeles, CA).

Biochemical measurements

Glucose was measured using YSI 2300 STAT Plus Glucose & Lactate Analyzer (YSI Life Sciences, Yellow Springs, OH), with a coefficient of variation (CV) of 1%. Insulin was measured by RIA (Milipore, St. Charles, MO) with a CV of 8.2%. Triglyceride, cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol were measured using Poly-Chem System Analyzer (Cortlandt Manor, NY) with CVs of 3.5%, 4% and 3.6%, respectively. Leptin and adiponectin were measured using RIA (Millipore, St. Charles, MO) with CVs of 4.3% and 6.5%. hs-CRP was measured using a highly sensitive (hs) latex-enhanced immunonephelometric assay with a CV <5%. Total testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and DHEAS were measured by RIA (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX) with CVs of 8.3%, 4.4% and 9.6%, respectively.

Calculations

Peripheral insulin resistance was assessed by calculating Matsuda’s sensitivity × fasting insulin) × (mean glucose × index (ISIMatsuda: 10,000/square root of [(fasting glucose mean insulin during OGTT)]) and SI by applying the MINIMOD program to FSIVGTT data. Hepatic insulin resistance was assessed by calculating Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA: [(fasting insulin (μU/ml) × fasting glucose (mg/dl))/405. Early insulin secretion was assessed by calculating AIRg from FSIVGTT. Pancreatic function was assessed by calculating the area under the curve (AUC) for insulin during OGTT and calculating β-cell function during FSIVGTT. β-cell compensation for insulin resistance was assessed by calculating DI from AIRg and SI.

Statistical analysis

The SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each outcome in each intervention group of patients, before and after intervention. The data were log-transformed in order to improve the normality of residuals and homoscedasticity of errors where appropriate before analysis. Paired t-test was performed to determine the significance of within-group change in each outcome, for each intervention. Inter-group comparisons were performed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), adjusted for the baseline values. When the overall difference among the groups was significant in ANCOVA, post-hoc pair wise group comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni multiple comparisons procedure to determine which groups significantly differed from each other. The longitudinal trajectories for changes in glucose and insulin during OGTT were estimated by repeated measures analysis of variance. Individual trajectories for changes in glucose and insulin were estimated from linear random-effects models. Each observed level was entered as the dependent variable. Treatment, time, and treatment × time interaction term were entered as independent variables. The coefficients for the interaction term were to estimate the additional changes in glucose and insulin level over time associated with treatment. To account for between-subject heterogeneity in the change of glucose or insulin level, intercept and time were modeled as random effects. Because we studied the differences at 6 weeks after intervention, we only included the subjects (n=51) with the endpoint measurements in the analysis. For those subjects, there were no missing endpoint values. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

There were no significant differences in the baseline data of the three intervention groups.

Diet

Macronutrient intake did not change significantly during the study. Baseline diet contained 1,945±127 kcal, 33.8% fat, 50.4% carbohydrate, 16.4% protein, 15.0±1.2 g fiber, 282±73 mg cholesterol, 4.48±0.59 g n-6 PUFA and 0.43±0.07 g n-3 PUFA. The diet at the end of the study contained 1,735±145 kcal, 34.8% fat, 48.2% carbohydrate, 16.9% protein, 15.7±1.5 g fiber, 214±4 mg cholesterol, 4.16±0.53 g n-6 PUFA and 0.43±0.06 g n-3 PUFA (excluding the PUFA from the supplements).

Anthropometric variables (Table 2)

Table 2.

Changes in anthropometric parameters, glucose homeostasis variables, plasma lipids and androgens during fish oil, flaxseed oil or soybean oil supplementations for six weeks in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

| Fish Oil (n=17) | Flaxseed Oil (n=17) | Soybean Oil (n=17) | ANOVA (Weight adjusted) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| Age (years) | 31.7 ±1.9 | --- | 29.4 ± 1.6 | --- | 28.9 ± 1.0 | --- | |

| Anthropometrics | |||||||

| Weight (kg) | 100.0 ± 5.2 | 100 ± 5 | 94.1± 8.2 | 94.5 ± 8.2 | 90.0 ± 5.9 | 90.5 ± 5.5 | -- |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 36.3 ± 1.9 | 36.6 ± 1.8 | 35.0± 2.5 | 35.1 ± 2.6 | 33.2± 1.8 | 33.3 ± 1.7 | 0.8418 |

| Waist (cm) | 99.3 ± 4.1 | 100.1 ± 3.8 | 95.0 ± 5.1 | 95.0 ± 5.0 | 94.7 ± 3.8 | 95.5 ± 3.8 | 0.5911 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 37.9 ± 3.8 | 38.5 ± 3.7 | 34.7± 4.2 | 34.1 ± 4.7 | 37.0 ± 4.1 | 35.3 ± 2.8 | 0.9471 |

| Fasting parameters | |||||||

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 5.44 ± 0.17 | 5.38 ± 0.11 | 5.16 ± 0.05 | 5.33 ± 0.17 | 4.94 ± 0.11 | 5.05 ± 0.11 | 0.5584 |

| Insulin (pmol/l) | 153 ± 17 | 158 ± 15 | 173 ± 40 | 188 ± 33 | 122 ± 17 | 132 ± 15 | 0.8005 |

| HgBA1 (%) | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1† | 5.5± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 5.4± 0.1 | 5.3± 0.1 | 0.8911 |

| Adiponectin (ng/ml) | 7.5 ± 1.0 | 8.5 ± 1.3 | 8.0±1.2 | 7.6 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 0.1988 |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 29.8 ± 3.5 | 29.4 ± 3.2 | 27.1 ± 3.3 | 28.5 ± 4.0 | 28.1± 3.4 | 30.6± 4.3 | 0.4042 |

| HOMA | 5.46 ± 0.68 | 5.55 ± 0.58 | 5.91 ± 1.47 | 6.78 ± 1.43 | 3.92 ± 0.59 | 4.32 ± 0.53 | 0.4208 |

| Oral Glucose tolerance test | |||||||

| ISIMatsuda | 2.43 ± 0.37 | 1.96 ± 0.25* | 2.46 ± 0.41 | 2.36 ± 0.38 | 3.27 ± 0.42 | 2.86 ± 0.42 | 0.4903 |

| AUCGlucose | 15.65 ± 0.61 | 16.48 ± 0.61 | 15.93 ± 0.44 | 15.71 ± 1.00 | 14.82 ± 0.61 | 16.37 ± 0.72* | 0.6973 |

| AUCInsulin | 1,760 ± 229 | 1,979 ± 236 | 1,924 ± 333 | 1,778 ± 319 | 1,292 ± 194 | 1,458 ± 194 | 0.2311 |

| Intravenous glucose tolerance test | |||||||

| AIRg | 893 ± 171 | 786 ± 129† | 627 ± 81 | 666± 94 | 669 ± 89 | 550 ± 74 | 0.1469 |

| DI | 1212 ± 189 | 1441 ± 239 | 956± 173 | 965 ± 113 | 1,784 ± 436 | 1100 ± 158 | 0.0621 |

| SI | 1.53 ± 0.24 | 1.78 ± 0.40 | 1.60 ± 0.23 | 2.98 ± 1.30 | 3.13 ± 0.76 | 2.45 ± 0.51 | 0.4028 |

| B cell function | 319 ± 63 | 331 ± 50 | 370 ± 51 | 343± 53 | 343 ± 49 | 315 ± 42 | 0.9651 |

| Fasting lipids and CRP | |||||||

| Triglyceride (mmol/l) | 1,47 ± 0.15 | 1.20 ± 0.14* | 1.62 ± 0.24 | 1.31 ± 0.17* | 1.39 ± 0.17 | 1.45 ± 0.19 | 0.0368 |

| Total-C (mmol/l) | 4.95 ± 0.21 | 5.10 ± 0.21 | 4.69 ± 0.23 | 4.69 ±0.23 | 4.92 ± 0.18 | 4.61 ± 0.21 | 0.1625 |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 3.29 ± 0.18 | 3.44 ± 0.21 | 2.77 ± 0.16 | 2.93 ± 0.18 | 2.87 ± 0.21 | 2.56 ± 0.26 | 0.0678 |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 1.06 ± 0.05 | 1.11 ± 0.05 | 1.17 ± 0.08 | 1.17 ± 0.05 | 1.22 ± 0.09 | 1.22 ± 0.08 | 0.7764 |

| ApoB (mg/dl) | 83 ± 5 | 86 ± 5 | 65 ± 12 | 64± 2 | 77 ± 4 | 77 ± 6 | 0.4381 |

| hs-CRP (mg/l) | 3.6±0.8 | 3.2±0.8 | 3.1±0.7 | 3.6±1.0 | 3.5±0.8 | 3.3±0.6 | 0.9575 |

| Androgens | |||||||

| Testosterone (nmol/l) | 2.95± 0.69 | 2.85 ± 1.11 | 2.95 ± 0.18 | 2.78 ± 0.62 | 3.33 ± 0.73 | 3.05 ± 0.76* | 0.7843 |

| SHBG (nmol/l) | 17.2 ± 2.5 | 17.2 ± 2.8 | 17.7± 3.5 | 16.3 ± 3.7 | 18.4 ± 2.4 | 16.2 ± 2.5 | 0.3896 |

| DHEAS (μmol/l) | 392 ± 70 | 392 ± 65 | 491± 75 | 504 ± 55 | 705 ± 57 | 653 ± 68 | 0.4933 |

Within group significance p < 0.05

Within group significance p = 0.0871

Weight, BMI, fat mass and waist circumference did not change during the intervention.

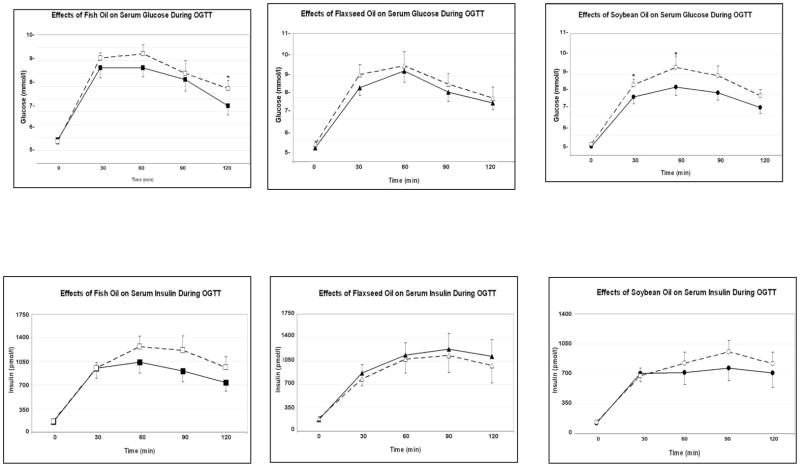

Glucose homeostasis variables (Table 2 and Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Effects of fish, flaxseed and soybean oils on serum glucose and insulin during oral glucose tolerance test (continuous lines: baseline; broken lines: after treatment; *; p < 0.05; Mean ± SEM; n = 17 in each group).

Fasting glucose, insulin, adiponectin, leptin, and HOMA did not change in any of the intervention groups.

When the baseline results were compared to after-study results, within group comparisons showed that fish oil increased serum glucose at 120 min (from 6.9±0.4 to 7.7±0.4, p = 0.0355) and tended to increase insulin at 60 min (from 1,028±159 to 1,201±213 pmol/l, p = 0.0941) while decreasing the Matsuda index (from 2.43±0.37 to 1.96±0.25, p = 0.0378). Fish oil tended to decrease the early insulin response measured by FS-IVGTT (AIRg) (p=0.0871). However, when overall glycemia was considered, fish oil caused a small but significant decrease in HgBA1 from 5.5±0.09% to 5.4±0.09% (p = 0.0030).

During fish oil treatment, the change in adiponectin correlated inversely with the changes in fasting glucose (r = −0.6041, p= 0.0102) and AUCGlucose (r= −0.4334, p = 0.0822). In addition, the change in hs-CRP correlated positively with the changes in fasting insulin (r= 0.6176, p= 0.0245) and triglyceride (r= 0.6348, p= 0.0198), and inversely with the change in Matsuda Index (r= −0.06348, p= 0.0299).

Flaxseed oil tended to increase glucose at 30 min of OGTT (from 8.3±0.4 to 8.9±0.5 mmol/l, p = 0.0883) but did not increase insulin at any time point. The change in hs-CRP was correlated inversely with the changes in HDL-cholesterol (r= −0.5243, p= 0.0448) and Matsuda Index (r= −0.4585, p= 0.0857).

Soybean oil increased glucose levels at 30 min (from 7.7±0.4 to 8.3± 0.3 mmol/l, p = 0.0333) during OGTT with borderline increase in glucose at 90 min (p = 0.0941); AUCGlucose increased significantly (from 14.82±0.61 to 16.37±0.72, p = 0.0122). Soybean oil tended to increase insulin at 90 min (from 757±144 to 949±132 pmol/l, p = 0.0558). During IVGTT, soybean oil tended to decrease early insulin response (AIRg) (p = 0.0848). The change in AUCInsulin correlated with the change in leptin (r= 0.5010, p = 0.0571).

The overall intergroup comparison showed that DI response tended to differ among the three intervention groups (p = 0.0621).

Fasting lipids and hs-CRP

When after intervention levels compared to the baseline, both fish and flaxseed oils decreased serum triglyceride significantly (p = 0.0154 and p = 0.0176, respectively) while soybean oil had no significant change. There was a significant inter group difference in triglyceride response change (p = 0.0368), which was primarily due to the difference between fish oil vs. soybean oil interventions (Bonferroni post-hoc test p = 0.0545). None of the oils altered serum total-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol or apoprotein B. However, there tended to be inter group differences in the LDL-C response (p = 0.0678) as fish and flaxseed oils tended to increase LDL-C while soybean oil tended to decrease it.

Androgens

After intervention, soybean oil reduced testosterone significantly (from 3.33±0.73 to 3.05±0.76 nmol/l, p = 0.0216) and tended to reduce SHBG (from 18.4±2.4 to 16.2±2.5 nmol/l, p = 0.0858), without affecting DHEAS. Fish and flaxseed oils did not affect testosterone, SHBG or DHEAS.

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of the study was to compare the effects of the essential vs. the long chain n-3 PUFA (flaxseed vs. fish oils). The secondary objective was to compare the n-3 vs. n-6 PUFA rich oils (flaxseed and fish oils vs. soybean oil). Fish and soybean tended to have similar effects on glucose homeostasis, which differed from the effects of flaxseed oil. On the other hand, fish and flaxseed oils tended to have similar effects on the lipid metabolism, which differed from the effects of soybean oil.

Changes in glucose homeostasis have two-fold relevance in PCOS. First, PCOS patients have increased insulin resistance and a higher risk of developing impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Second, changes in glucose homeostasis affect lipid metabolism and androgen production 14.

This study demonstrated that, when compared to the baseline, fish oil increased glucose levels during OGTT and tended to increase insulin levels during the second half of OGTT and decreased insulin sensitivity index (Matsuda), without significantly affecting fasting glucose, insulin or HOMA. Although the late insulin response tended to increase, the early insulin response measured by FS-IVGTT (AIRg) tended to decrease. Recent literature indicated that the patterns of change during OGTT point to the site of insulin resistance 15. Increased fasting glucose, insulin and HOMA suggest increased hepatic insulin resistance. On the other hand, increased glucose and insulin levels during the second half of OGTT and decreased Matsuda Index suggest increased peripheral insulin resistance. Accordingly, fish oil appeared to increase peripheral insulin resistance and decrease early insulin secretion. However, the late increase in insulin secretion compensated for the insulin resistance because disposition index tended to increase, and HgBA1c decreased. Notably, flaxseed oil did not change glucose homeostasis significantly, expect for the increase in 30 min-OGTT glucose.

To our knowledge, differential effects of different n-3 PUFA have not been investigated in PCOS patients. In healthy men and women, fish oils have not affected insulin sensitivity or early phase insulin response, regardless of the background fat intake or n-6/n-3 PUFA ratio 16, 17. In diabetic patients, low dose of fish oil supplementation has not affected hepatic or peripheral insulin resistance 18 while a high-dose increased glucose levels and decreased peripheral glucose utilization19. Several earlier studies have demonstrated increased glucose levels during fish oil treatment in diabetic patients 6. A recent population study indicated that fish consumption may be associated with increased risk of diabetes 20. Flaxseed oil has not altered fasting glucose, insulin or HgBA1c in diabetic patients either 21. These findings are in contrast with the data from animal models which have consistently shown that n-3 PUFA increase insulin sensitivity and glucose utilization 6. Studies in human muscle have demonstrated that monounsaturated fatty acid and PUFA contents of the cell membrane correlate directly with the glucose uptake 22. A potential explanation for the failure of n-3 PUFA in increasing insulin sensitivity in PCOS may relate to the underlying mechanism: Glucose uptake requires binding of insulin to its receptor in the cell membrane, followed by serial phosphorylation steps that occur in the insulin receptor (IR) and its substrate (IRS). Phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the IR and IRS-1 advances insulin signaling. In contrast, serine phosphorylation of the IRS-1 reduces insulin signaling and glucose transport. n-3 PUFA overcomes insulin resistance by preventing serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 23. Women with PCOS have intrinsic increase in serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 24. It is conceivable that n-3 PUFA cannot reverse this intrinsic abnormality, and therefore, cannot correct insulin resistance. To test this hypothesis, effects of n-3 PUFA in PCOS vs. healthy control women need to be compared.

During fish oil treatment, the changes in adiponectin levels correlated inversely with the changes in fasting glucose and AUCGlucose. This is consistent with the well recognized role of adiponectin in promoting insulin sensitivity. Experimental data indicate that adiponectin lowers fasting glucose by reducing hepatic glucose output and increases peripheral insulin sensitivity by promoting lipid oxidation 25. Although we have not observed any significant increase in adiponectin during fish oil intervention, studies in animal models and humans have reported significant increase17, 26, 27. In addition, hs-CRP correlated directly with the changes in fasting insulin and triglyceride, and inversely with the change in Matsuda Index. This is consistent with the well established role of inflammation in insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome 28.

Similar to fish oil, soybean oil also decreased early insulin response, increased glucose and insulin levels during the second half of OGTT and tended to decrease Matsuda Index--all pointing to increased insulin resistance and impaired early insulin secretion. The change in AUCInsulin correlated with the change in leptin. This finding can be explained by the strong correlation between serum leptin and obesity 29 as well as the role of insulin in leptin secretion from the adipose tissue 30. The main difference between fish oil vs. soybean oil treatments was that the disposition index tended to increase during fish oil intervention but tended to decrease during soybean oil intervention. These findings suggest that glucose disposal to the peripheral tissues was maintained during fish oil but not during soybean oil intervention. The similarities between the effects of fish and soybean oils were unexpected because the major PUFA in the fish oil belong to the n-3 class whereas in soybean oil to the n-6 class (Table 1). Although there is limited information about the effects of soybean oil on glucose homeostasis, in vitro studies in rat pancreas have shown that soybean oil can decrease 31 or increase 32 insulin secretion.

When the changes in lipid metabolism were considered, both fish and flax seed oils decreased triglyceride and tended to increase LDL-cholesterol. It is well established that long chain n-3 PUFA in fish oil decrease triglyceride and increase LDL-cholesterol 7. Effects of flaxseed oil on triglyceride and LDL-cholesterol have been variable 33. The literature about the effects of soybean oil on plasma lipids is not readily comparable to our study because most published reports have tested the effects of hydrogenated soybean oil or soybean itself.

An important finding was that none of the supplements affected the hs-CRP levels. In PCOS, obesity and central obesity both have been associated with elevated hs-CRP levels 34. We had expected fish oil and flaxseed oil to lower hs-CRP due to their well recognized anti-inflammatory effects 35–37, while soybean oil increases hs-CRP because n-6 PUFA are pro-inflammatory 38. Although population studies in the USA 35, 39 and Greece 40 have shown inverse relationships between hs-CRP and n-3 PUFA intake, a study in Japan also showed inverse correlation between intake of n-6 essential PUFA and hs-CRP 41, suggesting that n-6 PUFA can also be anti-inflammatory. The results obtained from cross-sectional population studies may not be directly applicable to prospective intervention studies because neither our intervention nor a recent report from Gillingham et al 42 found a decrease in hs-CRP during n-3 PUFA supplementation. Changes in hs-CRP correlated with the changes in insulin resistance markers, consistent with the well accepted role of inflammation in increased insulin resistance 43.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that long chain vs. essential n-3 PUFA rich oils from marine vs. plant sources exert specific effects on glucose homeostasis in PCOS patients. The long chain n-3 PUFA rich fish oil and n-6 PUFA rich soybean oil supplements can decrease early insulin secretion, can impair glucose tolerance and increase hyperinsulinemia. On the other hand, the essential n-3TPUFA rich flaxseed oil does not have any adverse effects. It is necessary to monitor blood glucose in PCOS patients after starting any PUFA supplementation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants to Dr. Karakas from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM, Grant number: NCCAM: AT003401) and the ALSAM Foundation, Los Angeles, CA. The clinical studies were partially supported by the UC Davis Clinical and Translational Science Center Grant (RR 024146).

ABBREVIATION LIST

- PCOS

polycystic ovary syndrome

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- FS-IVGTT

frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- IRS

insulin receptor substrate

- AUC

area under the curve

- SHBG

sex hormone binding globulin

- DHEAS

dehydroepiandrostenedione

- HOMA

Homeostasis Model Assessment

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

Institutional approval: The study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the UC Davis and all subjects signed the approved informed consent.

Clinical Trial #: NCT 022715060-1

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ehrmann DA. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1223–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohlig M, Spranger J, Osterhoff M, et al. The polycystic ovary syndrome per se is not associated with increased chronic inflammation. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:525–32. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qin KN, Rosenfield RL. Role of cytochrome P450c17 in polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;145:111–21. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunaif A. Citation for the 2000 Monsanto Clinical Investigator Award Lecture of The Endocrine Society to Dr. William F. Crowley. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:449–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cussons AJ, Watts GF, Mori TA, Stuckey BG. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation decreases liver fat content in polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial employing proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3842–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasim-Karakas S, editor. Omega-3 fish oils and insulin resistance. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasim-Karakas S. Omega-3 fish oils and lipoprotein metabolism. 2. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arterburn LM, Hall EB, Oken H. Distribution, interconversion, and dose response of n-3 fatty acids in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1467S–76S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1467S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall LA, Johnston PV. Modulation of tissue prostaglandin synthesizing capacity by increased ratios of dietary alpha-linolenic acid to linoleic acid. Lipids. 1982;17:905–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02534586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azziz R. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: a reappraisal. Fertility and sterility. 2005;83:1343–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalgaonkar S, Almario RU, Gurusinghe D, et al. Differential effects of walnuts vs almonds on improving metabolic and endocrine parameters in PCOS. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eslick GD, Howe PR, Smith C, Priest R, Bensoussan A. Benefits of fish oil supplementation in hyperlipidemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierson RN, Jr, Wang J, Thornton JC. Measurement of body composition: applications in hormone research. Hormone research. 1997;48 (Suppl 1):56–62. doi: 10.1159/000191271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasquali R, Gambineri A. Targeting insulin sensitivity in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:1205–26. doi: 10.1517/14728220903190699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdul-Ghani MA, Matsuda M, Balas B, DeFronzo RA. Muscle and liver insulin resistance indexes derived from the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:89–94. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giacco R, Cuomo V, Vessby B, et al. Fish oil, insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion and glucose tolerance in healthy people: is there any effect of fish oil supplementation in relation to the type of background diet and habitual dietary intake of n-6 and n-3 fatty acids? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17:572–80. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itoh M, Suganami T, Satoh N, et al. Increased adiponectin secretion by highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid in rodent models of obesity and human obese subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1918–25. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.136853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabir M, Skurnik G, Naour N, et al. Treatment for 2 mo with n 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces adiposity and some atherogenic factors but does not improve insulin sensitivity in women with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1670–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mostad IL, Bjerve KS, Bjorgaas MR, Lydersen S, Grill V. Effects of n-3 fatty acids in subjects with type 2 diabetes: reduction of insulin sensitivity and time-dependent alteration from carbohydrate to fat oxidation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:540–50. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.3.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaushik M, Mozaffarian D, Spiegelman D, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, fish intake, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:613–20. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barre DE, Mizier-Barre KA, Griscti O, Hafez K. High dose flaxseed oil supplementation may affect fasting blood serum glucose management in human type 2 diabetics. J Oleo Sci. 2008;57:269–73. doi: 10.5650/jos.57.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baur LA, O’Connor J, Pan DA, Kriketos AD, Storlien LH. The fatty acid composition of skeletal muscle membrane phospholipid: its relationship with the type of feeding and plasma glucose levels in young children. Metabolism. 1998;47:106–12. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma QL, Yang F, Rosario ER, et al. Beta-amyloid oligomers induce phosphorylation of tau and inactivation of insulin receptor substrate via c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling: suppression by omega-3 fatty acids and curcumin. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9078–89. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1071-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunaif A, Xia J, Book CB, Schenker E, Tang Z. Excessive insulin receptor serine phosphorylation in cultured fibroblasts and in skeletal muscle. A potential mechanism for insulin resistance in the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:801–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI118126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravussin E. Adiponectin enhances insulin action by decreasing ectopic fat deposition. Pharmacogenomics J. 2002;2:4–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lara JJ, Economou M, Wallace AM, et al. Benefits of salmon eating on traditional and novel vascular risk factors in young, non-obese healthy subjects. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193:213–21. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neschen S, Morino K, Rossbacher JC, et al. Fish oil regulates adiponectin secretion by a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-dependent mechanism in mice. Diabetes. 2006;55:924–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-0985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karakas SE, Kim K, Duleba AJ. Determinants of impaired fasting glucose versus glucose intolerance in polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:887–93. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Havel PJ. Role of adipose tissue in body-weight regulation: mechanisms regulating leptin production and energy balance. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59:359–71. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreno-Aliaga MJ, Stanhope KL, Gregoire FM, Warden CH, Havel PJ. Effects of inhibiting transcription and protein synthesis on basal and insulin-stimulated leptin gene expression and leptin secretion in cultured rat adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;307:907–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobbins RL, Szczepaniak LS, Myhill J, et al. The composition of dietary fat directly influences glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in rats. Diabetes. 2002;51:1825–33. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Picinato MC, Curi R, Machado UF, Carpinelli AR. Soybean- and olive-oils-enriched diets increase insulin secretion to glucose stimulus in isolated pancreatic rat islets. Physiol Behav. 1998;65:289–94. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan A, Yu D, Demark-Wahnefried W, Franco OH, Lin X. Meta-analysis of the effects of flaxseed interventions on blood lipids. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:288–97. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puder JJ, Varga S, Kraenzlin M, De Geyter C, Keller U, Muller B. Central fat excess in polycystic ovary syndrome: relation to low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6014–21. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pischon T, Hankinson SE, Hotamisligil GS, Rifai N, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Habitual dietary intake of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in relation to inflammatory markers among US men and women. Circulation. 2003;108:155–60. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000079224.46084.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rallidis LS, Paschos G, Liakos GK, Velissaridou AH, Anastasiadis G, Zampelas A. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid decreases C-reactive protein, serum amyloid A and interleukin-6 in dyslipidaemic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2003;167:237–42. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsitouras PD, Gucciardo F, Salbe AD, Heward C, Harman SM. High omega-3 fat intake improves insulin sensitivity and reduces CRP and IL6, but does not affect other endocrine axes in healthy older adults. Horm Metab Res. 2008;40:199–205. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1046759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calder PC. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and immunity. Lipids. 2001;36:1007–24. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0812-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze MB, Manson JE, et al. Consumption of (n-3) fatty acids is related to plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial activation in women. J Nutr. 2004;134:1806–11. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.7.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalogeropoulos N, Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, et al. Unsaturated fatty acids are inversely associated and n-6/n-3 ratios are positively related to inflammation and coagulation markers in plasma of apparently healthy adults. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:584–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poudel-Tandukar K, Nanri A, Matsushita Y, et al. Dietary intakes of alpha-linolenic and linoleic acids are inversely associated with serum C-reactive protein levels among Japanese men. Nutr Res. 2009;29:363–70. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillingham LG, Gustafson JA, Han SY, Jassal DS, Jones PJ. High-oleic rapeseed (canola) and flaxseed oils modulate serum lipids and inflammatory biomarkers in hypercholesterolaemic subjects. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:417–27. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510003697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dandona P, Aljada A, Bandyopadhyay A. Inflammation: the link between insulin resistance, obesity and diabetes. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]