Abstract

Context

We compared the prevalence of alcohol use and other psychiatric disorders in offenders 15 years after a first conviction for driving while impaired with a general population sample.

Objective

To determine whether high rates of addictive and other psychiatric disorders previously demonstrated in this sample remain disproportionately higher compared with a matched general population sample.

Design

Point-in-time cohort study.

Setting

Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Participants

We interviewed convicted first offenders using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview 15 years after referral to a screening program in Bernalillo County, New Mexico. We calculated rates of diagnoses for non-Hispanic white and Hispanic women (n=362) and men (n=220) adjusting for missing data using multiple imputation and compared psychiatric diagnoses with findings from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication by sex and Hispanic ethnicity.

Results

Eleven percent of non-Hispanic white women and 12.8% of Hispanic women in the driving while impaired sample reported 12-month alcohol abuse or dependence, compared with 1.0% and 1.8%, respectively, in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (comparison) sample. Almost 12% of non-Hispanic white men and 17.5% of Hispanic men in the driving while impaired sample reported 12-month alcohol abuse or dependence, compared with to 2.0% and 1.8%, respectively, in the comparison sample. These differences were statistically significant. Rates of drug use disorders and nicotine dependence were also elevated compared with the general population sample, while rates of major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder were similar.

Conclusion

In this sample, high rates of addictive disorders persisted over 10 years among first offenders and greatly exceeded those found in a general population sample.

Keywords: DWI, drunk drivers, psychiatric disorder, mental health, comorbidity

INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades there has been a major decline in the percentage of traffic fatalities attributed to alcohol. Despite this, driving while under the influence or driving while impaired (DWI) continues to be a significant public health problem.1; 2 Nationally, alcohol-related crashes still remain at the unacceptably high rate of 32% of all fatal crashes. In 2008, an alcohol-related fatal crash occurred approximately every 45 minutes, totaling 11,773 deaths.3 Internationally, due to a variety of risk factors, including impaired driving, motor vehicle crashes will be the third most serious threat to human health in the world by 2020.4 How many lives are lost due to DWI by other drugs, alone or in combination with alcohol, is unknown.5; 6 In addition to the considerable emotional and physical pain caused by these crashes, the estimated economic cost of alcohol-related crashes in 2000 was $51 billion.7 As a society, we must do more to reduce the toll that impaired driving takes on our citizens.

Driving while impaired is a common crime. More Americans are arrested for DWI than for any other crime except drug possession.8 This is an arrest rate of one for every 139 licensed drivers in the U.S., constituting in 2008 over 1.48 million drivers.9 A DWI conviction is a significant event, for it identifies people who are at high risk of having or developing substance use disorders. However, the criminal justice system alone cannot prevent these offenders from repeating the offense. Most states mandate that offenders undergo screening to determine their need for treatment services,10 but offenders often underreport their substance use and related problems, leading to a substantial under-identification of those with alcohol and drug use disorders.11; 12 A high percentage of these offenders continue to drive after drinking, with 20 to 50% rearrested for DWI.13 These high rearrest rates are alarming; yet arrests are the tip of the iceberg. One study estimated that for every arrest, an impaired driver makes 50 to 200 trips that go undetected.14 As a result, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration places a special emphasis on reaching high-risk populations, including repeat offenders and drivers with high blood alcohol concentrations.15

Information on the longitudinal progression of alcohol use disorders among convicted DWI offenders has important implications, but we know little regarding the long-term course of addictive disorders among convicted DWI offenders. Cavaiola and colleagues evaluated factors associated with repeat offenses at 12-year follow-up among 77 first offenders, but they did not ascertain alcohol use or other psychiatric disorders.16 McCord followed 466 males from childhood to adulthood and examined factors associated with having a DWI conviction.17 She found that such men were more likely than those not convicted to be alcoholic and to have a conviction for other serious crimes. Our previous study interviewed a sample of 1,396 offenders 5 years after conviction for a first DWI offense with a court mandate to undergo screening.18 Among participants, 85% of women and 91% of men met diagnostic criteria for lifetime alcohol dependence or abuse. Thirty-three percent of women and 40% of men reported a 12-month alcohol abuse or dependence disorder. These rates and rates of drug use disorders far exceed the rates of substance use disorders in a matched general community sample, wherein fewer than 3.5% reported a lifetime alcohol or drug use disorder.18

We conducted the current study to provide information on the extent to which the high rates of addictive disorders found 5 years after screening persist, and how the prevalence of these disorders compares with their prevalence in the general community. To this end, we attempted to locate and interview this cohort 15 years after a screening referral. The objectives were to determine the rates of current alcohol and drug use disorders and other psychiatric disorders in this population, and to compare these rates with those obtained from a comparable sample surveyed from the general community.

METHODS

Design Overview

We selected the study population from a database of convicted DWI offenders referred to the Lovelace Comprehensive Screening Program (Screening Program) between April 1989 and March 1992. We interviewed 1,396 offenders 5 years after this referral (initial study), then located and reinterviewed this cohort 15 years after the initial screening referral (follow-up study). This is a point-in-time cohort study of a subgroup of individuals who were first-time offenders 15 years earlier. The primary analyses compared the DWI sample with participants in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) conducted between 2001 and 2003.19

Setting and Participants

The Screening Program had a contract with the Bernalillo County Metropolitan Court, New Mexico, to provide a comprehensive evaluation of first offenders to determine whether they had an alcohol- or drug-related disorder. The Court referred those deemed to have these disorders to community-based treatment options, and they were followed to determine whether they completed the treatment process. Traffic records and self-reported information indicated that about 80% were truly first offenders.20 This offender population was similar in age and marital status to other convicted DWI offender populations, but had a higher proportion of Hispanics and American Indians, compared to other U.S. studies. The mean blood alcohol concentration for DWI offenders in the Screening Program was 16%, around the middle of the range for mean blood alcohol concentrations of arrested drunk drivers elsewhere in the U.S.21

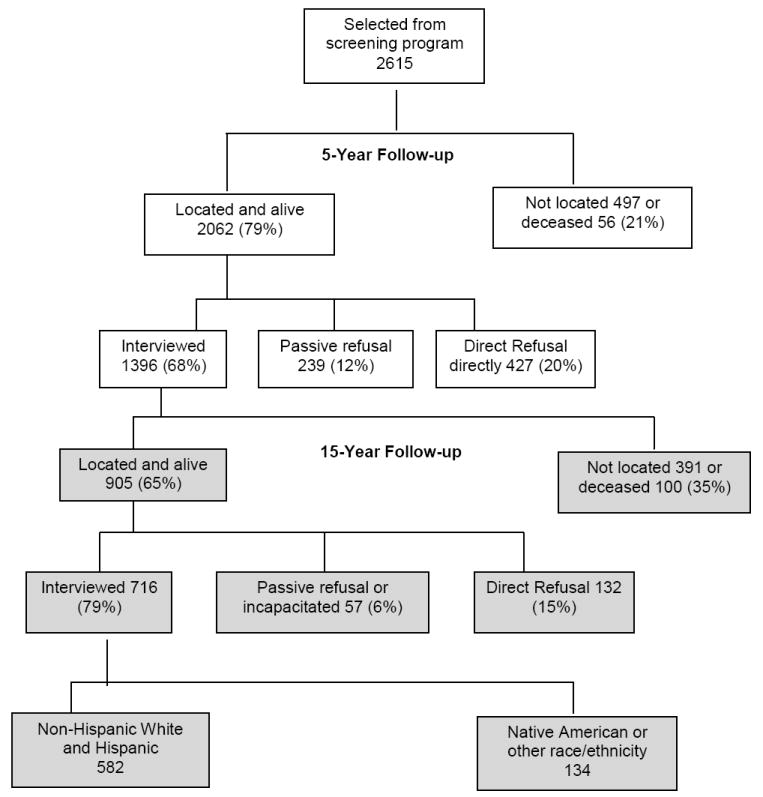

For the initial study we selected 1,208 consecutive female and 1,407 male referrals. We contacted subjects between June 1994 and June 1997 to determine the prevalence of psychiatric disorders. This was a community-based sample, since these offenders were selected regardless of whether they completed screening or the Court referred them to treatment. We have published the details regarding selection, location, and tracking of the study sample.22 We sent information about the nonlocated subjects to the National Death Index to match against death certificates. Of 2,615 selected subjects, 56 had died, and we could not locate 497 of the 2,615; we located 2,062 who were alive and interviewed 1,396 of them (Figure 1). Approximately 10 years later, we tried to locate and reinterview the 1,396 participants interviewed for the initial study. We submitted a list of identifiers for all subjects who, during the tracking process, had either died or we could not locate to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in January 2008, and staff there matched this list to the National Death Index. Of 1,396 subjects, 100 participants had died, and staff located 905 living subjects. We interviewed 716 subjects; 57 refused passively or were incapacitated, and 132 refused to be interviewed. Comparisons of those interviewed at 15-year follow-up to those originally selected and not known to be deceased (N=2,459) revealed that males, Mexican nationals, those with an arrest warrant, those without telephones, and those who did not complete screening were underrepresented in the 15-year follow-up sample (supplementary materials).

Figure 1.

DWI Study Flow Diagram

For the follow-up study the primary data source for locating clients was Screening Program record data; we used other databases as well. Bilingual (English and Spanish) staff used a comprehensive location protocol that the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation institutional review board approved. Protocols included a letter sequence, telephone calls, and home visits. Once located, willing participants provided written informed consent, and we gave them $100 to complete the interview. We trained our interviewers in administering the diagnostic instrument. We interviewed by telephone the out-of-town individuals (about 18% of those interviewed), and about 10% of those residing in-state, who lived far from the research site and/or were unable to visit the research site. We reviewed all interviews to monitor consistency and discussed discrepancies to standardize coding.

The diagnostic interview included demographic information and a computerized version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI).23; 24 The World Health Organization and the U.S. Mental Health Administration initially requested this interview to estimate prevalence rates of specific psychiatric disorders. CIDI questions are fully scripted, close-ended, highly structured, and appropriate for nonclinician interviewers to use. The version used, the 10th revision, provides DSM-IV diagnoses based on an individual’s responses. Disorders assessed for the present study included rates of 12-month alcohol and drug abuse and dependence, nicotine dependence, major depressive disorder (MDD), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We limited nonsubstance use-related diagnoses to MDD and PTSD because they were the two most prevalent disorders in the DWI offender population. Twelve-month prevalence is the percentage of subjects who, having met the diagnostic criteria once for a lifetime disorder, experienced symptoms of that disorder within the 12 months prior to the interview. We also asked subjects, “How often did you drive when you thought you might be over the legal blood alcohol limit [here designated as driving over the limit] for drunk driving in the past 3 months?” We compared the self-reported rates of driving over the limit among those with no alcohol diagnosis, alcohol abuse, and those with lifetime alcohol dependence.

Statistical Analysis

The NCS-R is a nationally representative sample of 9,282 English-speaking adults, conducted approximately contemporaneously with the final DWI interviews. It provides a suitable benchmark against which we could compare the DWI offender data. Both studies used the same diagnostic interview. We used SAS version 9.1.3 for all analyses.25 Means, standard deviations, and frequencies were the descriptive statistics.

We restricted the primary sample chosen for these comparisons to those who self-identified as being of non-Hispanic white or Hispanic ethnicity. The DWI sample comprised 134 individuals whose ethnicity we could not match with comparable individuals from the Comparison sample. The majority of them (96) were Native American. In the Comparison sample, we included Native Americans under “all other,” and they constituted 17.6% of that sample. Removing the 134 from the DWI sample resulted in a final matched sample of 582 individuals.

To address known gender differences in the prevalences of psychiatric comorbidity between males and females,26 we weighted the sample by age, adjusted the analysis by education, and conducted separate analyses by ethnicity and gender. This yielded four separate gender-ethnicity groups: gender crossed with non-Hispanic white vs. Hispanic ethnicity. In both the NCS-R and DWI studies we used a single item to assess ethnicity. We computed age in the year 2003 for all DWI subjects. For the DWI-NCS-R comparisons, we applied weights, calculated separately for each stratum, to the DWI sample to equate the two samples by age categories. The primary analyses were weighted logistic regressions. To adjust for years of education, we entered this variable into the analyses as a covariate. We accounted for multiple comparisons across strata and diagnoses by using a partial Bonferroni alpha level of 0.005 to determine statistical significance.

We used multiple imputation in our primary analyses because of missing data in the DWI sample. Multiple imputation for missing data has multiple advantages over earlier approaches to missing data, such as listwise deletion 27; it allows the inclusion of cases with one or more missing values, while taking into account the uncertainty introduced into the analysis by the imputation process. We did not impute for the minimal missing data in the Comparison sample. The variables included in the imputation model were an indicator variable for which cases had died: age; sex; education; blood alcohol concentration reading at the initial DWI arrest; ethnicity; three binary variables to indicate whether the participants at the initial interview were married, divorced, or single; and the status at the time of the initial interview of diagnoses for alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse or dependence, nicotine dependence, MMD, and/or PTSD. We generated 10 multiply imputed samples using Markov Chain Monte Carlo to accommodate non-monotone missing data patterns.

To determine whether inaccuracies in the imputation might affect our results, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. There, we made the extreme assumption that all missing observations would be contrary to results obtained from the imputations; namely, that all missing cases would have no alcohol, drug, or other diagnoses. We also conducted simple comparisons of the study participants in the DWI and Comparison samples whom we could not include in the stratified, weighted analyses described above. We treated all these participants as a single group and compared raw frequencies of disorders.

RESULTS

As found in the original study,18 the DWI sample exhibited age-adjusted rates of alcohol and drug use disorders, as well as nicotine dependence, which greatly exceeded those in the Comparison sample (Table 1). Unlike those in the original study, rates of MDD and PTSD were comparable to the Comparison sample. Rates of alcohol abuse or dependence among DWI offenders were significantly higher than those found in respective Comparison samples (Table 2). Rates of current drug use disorders were more than six times higher in the DWI population, compared with a general population (Table 1). The overall rate of self-reported driving over the limit in the 90 days before the last interview was 10%. Of 11 subjects with no lifetime alcohol diagnosis, no one reported driving over the limit; of 286 subjects with a lifetime alcohol abuse diagnosis, 7% reported driving over the alcohol limit; and among 279 with lifetime alcohol dependence, 14% reported this condition (Fisher’s exact p = 0.01). For drug abuse or dependence and for nicotine dependence, we found statistically significant differences among both ethnic groups of female offenders and females in the respective Comparison samples. Hosmer-Lemeshow tests indicated an adequate fit for the statistical models.

Table 1.

Estimated Rates of Self-Reported 12-Month Recency Diagnoses, DWI Offenders, and NCS* Samples, Equated for Age.**

| Diagnosis | Females | Males | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | Hispanic | |||||

| DWI Sample | Comp | DWI Sample | Comp | DWI Sample | Comp | DWI Sample | Comp | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Alcohol abuse | 18 (6.4) | 24 (0.9) | 25 (7.3) | 4 (1.4) | 13 (5.5) | 41 (1.8) | 19 (7.2) | 3 (1.4) |

|

| ||||||||

| Alcohol dependence | 9 (3.1) | 13 (0.5) | 15 (4.4) | 2 (0.7) | 8 (3.4) | 21 (0.9) | 10 (3.7) | 2 (0.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 18 (11.2) | 26 (1.0) | 26 (12.8) | 5 (1.8) | 12 (11.8) | 45 (2.0) | 20 (17.5) | 4 (1.8) |

|

| ||||||||

| Drug abuse or dependence | 9 (3.2) | 5 (0.2) | 21 (6.2) | 1 (0.4) | 8 (3.4) | 16 (0.7) | 11 (4.2) | 2 (0.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| Nicotine dependence | 38 (23.9) | 84 (3.2) | 28 (13.7) | 9 (3.3) | 12 (11.6) | 66 (2.9) | 8 (7.3) | 8 (3.6) |

|

| ||||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 36 (12.6) | 271 (10.2) | 36 (10.4) | 17 (6.2) | 16 (6.5) | 137 (6.0) | 17 (6.2) | 19 (8.6) |

|

| ||||||||

| PTSD*** | 24 (8.1) | 123 (4.6) | 35 (9.9) | 19 (6.9) | 60 (2.4) | 45 (2.0) | 6 (2.4) | 3 (1.4) |

NCS National Comorbidity Study-Replication (Comparison (Comp) group)

DSM-IV Diagnoses obtained from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) for the New Mexico sample. New Mexico percentages are multiple imputation estimates.

PTSD Posttraumatic stress disorder

Table 2.

| Psychiatric Disorder | Non-Hispanic White Females | Hispanic Females | Non-Hispanic White Males | Hispanic Males | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95%CL***) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95%CL) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95%CL) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95%CL) | p-value | |

| Alcohol abuse | 6.81 (3.19-14.51) | <.001 | 5.31 (1.72-16.5) | .004 | 3.09 (1.25-7.64) | .02 | 5.71 (1.54-21.3) | .01 |

|

| ||||||||

| Alcohol dependence | 8.01 (2.27-28.2) | .002 | 6.66 (1.39-31.9) | .01 | 4.25 (1.36-13.3) | .01 | 4.37 (.823-23.2) | .08 |

|

| ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 12.9 (6.89-24.0) | <.001 | 7.85 (2.95-20.9) | <.001 | 6.71 (3.46-13.0) | <.001 | 12.2 (3.95-37.5) | <.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Drug abuse or dependence | 26.5 (4.71-148.7) | .001 | 22.3 (2.65-187) | .004 | 7.24 (1.76-29.7) | .008 | 6.70 (1.07-41.9) | .04 |

|

| ||||||||

| Nicotine dependence | 6.03 (3.25-11.2) | <.001 | 3.58 (1.51-8.52) | .004 | 3.19 (1.45-7.01) | .005 | 1.68 (.523-5.42) | .38 |

|

| ||||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 1.44 (.641-3.20) | .34 | 1.91 (.840-4.34) | .12 | 1.31 (.425-4.05) | .62 | 0.781 (.195-3.13) | .71 |

|

| ||||||||

| PTSD**** | 1.98 (.762-5.14) | .15 | 1.60 (.742-3.46) | .22 | 1.63 (.344-7.78) | .52 | 2.43 (.357-16.6) | .36 |

National Comorbidity Survey (Comparison (Comp) Group)

We used multiple imputation parameter estimates to adjust for missing data for those not interviewed at time 2. Samples (DWI sample only) were weighted by age and covaried for education and blood alcohol concentration at the time of initial arrest

CL Confidence Limits arrest.

PTSD Posttraumatic stress disorder

Results of the sensitivity analysis paralleled those in the stratified analyses, with strong differences for alcohol, drugs, and nicotine, but no significant difference for psychiatric disorders. When we performed an analysis in which we assumed that none of the missing DWI cases would have an alcohol or drug diagnosis, we discovered that where the multiple imputation analyses differed significantly, the sensitivity analyses confirmed the direction of results in all instances. As expected, p-values from the sensitivity analysis were weaker, but seven tests still met the 0.005 alpha level: four were between 0.005 and 0.05, and one was greater than 0.05. Results from participants who had other ethnicities also paralleled our primary analyses.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to follow a large cohort of DWI offenders for an extended time period. Our findings show that in this sample a DWI conviction, even in the distant past, identifies a subgroup of people with high rates of current substance use disorders. Rates of alcohol abuse or dependence in the DWI population are more than five times higher than in the comparable general population sample. This has important public health implications, for those in our study with lifetime alcohol dependence reported twice the rate of driving over the limit, compared with subjects reporting no diagnosis or alcohol abuse. The first-offender population in our study also was at high risk for crash involvement. Of the 1,396 offenders in the initial study, 588 (42%) were subsequently involved in a crash, with 347 (24.9%) involved in one crash, 158 (11.3%) in two crashes, and 83 (5.9%) three or more crashes.28

Based on these findings, we recommend enlisting health and mental health care providers to address DWI issues in clinical contexts to help identify and intervene with those at risk for chronic impaired-driving behavior. We suggest asking directly about a patient’s DWI history. Clinical practice guidelines for those with chronic addictions recommend intensive addiction treatment followed by outpatient treatment for a period of time.29 These individuals also may benefit from ongoing monitoring and early reintervention, following treatment discharge.30 Such practices promote abstinence and reduce the likelihood of re-arrest.30 Medication-assisted treatment is another promising, if underutilized, treatment modality.31 One preliminary study revealed that an extended-release form of injectable naltrexone reduced drinking in a small sample of chronic DWI offenders.32 Moreover, a post-hoc analysis showed an association between this medication, combined with psychosocial support among alcohol-dependent patients who had maintained at least 4 days of continuous abstinence before starting treatment, and a significant reduction in alcohol consumption during holiday periods, when alcohol-related crashes peak.33 Excessive alcohol intake during major holidays contributes to about 40% of all traffic fatalities.34 These studies suggest that treatment including medication and monitoring of sobriety may be an effective means for reducing chronic recidivism.

This study is the first to determine the persistence of addictive disorders in a nontreatment DWI sample having a high prevalence of addictive and other psychiatric disorders. Alcohol and drug use disorders are chronic relapsing conditions.35 Thus, we anticipated that rates of alcohol and drug use disorders among DWI offenders with a demonstrated high prevalence of addictive disorders might continue to exceed those found in a community sample. Several longitudinal studies have followed patients treated for alcohol dependence for 10 years or more to determine long-term outcomes.36-40 Remission rates vary tremendously in these samples, and methodological differences make it difficult to compare recovery rates.41 Findings for treatment samples do not generalize to DWI offenders, as treated populations are more likely than community samples to have severe dependence and other comorbid psychiatric disorders.42 We found that rates of current substance use disorders decreased substantially from those ascertained at the initial interview. This is consistent with findings that prevalence rates of substance use disorders decline with age.43 Subjects with substance use disorders in the original sample were also more likely to be deceased at the 15-year follow-up interview than those interviewed initially.28

Rates of alcohol use disorders found in the DWI sample exceeded prevalence rates from other national surveys that did not use the CIDI to determine diagnoses. Two nationally representative surveys—the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions and the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 1991–1992 National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey—ascertained prevalence rates of 12-month DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in 2001–2002 using face-to-face interviews. In the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions and the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey, the prevalences were 6.93% for males and 2.55% for females.44

The NCS-R, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, and National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey studies all found that alcohol use disorders are much more prevalent among males than females. It is noteworthy that the discrepancy between rates of addictive disorders in the DWI and Comparison groups in our study was much higher for females than for males, with both genders in the DWI sample having nearly equal rates of alcohol and drug use disorders. Rates of nicotine dependence were particularly elevated in the female offender subgroups. These findings are consistent with other studies in which the percentage of DWI offenders meeting lifetime criteria for alcohol dependence is similar to, or higher, among women than men.45-47

In contrast to findings in the initial study,18 rates of MDD and PTSD in this study were comparable to those found in the community sample. For the analysis we used a multiple imputation procedure that accounted for deaths and other possible biases, and the sample sizes were adequate. Therefore, the lack of significance probably is not due to selective attrition, though we cannot rule that out entirely.

A major limitation of this study is the low participation rate, a problem inherent to longitudinal studies of criminal justice populations.48-51 Those with a good reason to avoid detection (those with arrest warrants or who were in the country illegally), as well as hard-to-reach subjects with no telephones, were either not located or were more likely to refuse participation. Although we attempted to adjust for biases introduced due to loss to follow-up, rates of psychiatric disorders in this population may not be representative of the general U.S. population of DWI offenders. The sensitivity analysis confirmed the direction of results in all instances, however. Another study limitation is that the interview used for both studies, the NCS-R version of the CIDI, may have underestimated the prevalence of substance dependence symptoms unless the respondents were positive for abuse. DWI offenders may be more likely to qualify for a diagnosis of abuse, as repeated driving under the influence of alcohol is one criterion for alcohol abuse.52 Other study limitations are the limited number of psychiatric diagnoses compared, sampling from a single locale, the use of self-report measures to ascertain psychiatric diagnoses using structured interviews for both the DWI and NCS-R studies, and no clinical confirmation of psychiatric disorders. We had to eliminate Native Americans and those of other races from the primary analysis because of insufficient sample sizes.

In conclusion, compared with a matched community sample, this longitudinal study found extremely high rates of addictive disorders among convicted first DWI offenders, particularly among women, 15 years after a screening referral, and similar rates of MDD and PTSD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Alroy, Michael Lackey, Vivian Fernandez, and Catherine Cummins for conducting the interviews, Elizabeth Wozniak for manuscript preparation, and all the study participants for completing the interviews.

Funding The authors disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research and authorship of this article: The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Grant #R01 AA014750.

The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Sandra C. Lapham, Email: slapham@bhrcs.org.

Robert Stout, Email: stout@pire.org.

Georgia Laxton, Email: glaxton@cox.net.

Betty J. Skipper, Email: skipperbetty@yahoo.com.

Reference List

- 1.Kelley-Baker T, Lacey J, Brainard K, Kirk H, Taylor E. DOT HS 810 647. Washington, D.C.: National Hightway Traffic Safety Administration; 2006. Citizen Reporting of DUI-Extra Eyes to Identify Impaired Driving. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. DOT HS 811 175. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation; 2009. Traffic safety facts research note: Results of the 2007 National Roadside Survey of Alcohol and Drug Use by Drivers. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Impaired Driving. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; [April 4, 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. DOT HS 811 155. Washington, DC: National Center for Statistics and Analysis; 2009. Traffic Safety Facts 2008 Data: Alcohol-impaired Driving. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global Road Safety. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [April 4, 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogden EJ, Moskowitz H. Effects of alcohol and other drugs on driver performance. Traffic Inj Prev. 2004;5:185–198. doi: 10.1080/15389580490465201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kay GG, Logan BK. DOT HS 811 438. Washington, D.C.: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2011. Drugged Driving Expert Panel Report: A Consensus Protocol for Assessing the Potential of Drugs to Impair Driving. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blincoe L, Seay A, Zaloshnja E, Miller T, Romano E, Luchter S. DOT HS 809 446. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 30 1, 2002. The Economic Impact of Motor Vehicle Crashes, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S.Department of Justice. 2008 Crime in the United States, Table 29: Estimated number of arrests. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division; 2011. [March 23, 2010]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. DOT 810 809. Washington DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2008. Traffic Safety Facts 2006: Overview. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beirness DJ, Simpson HM, Mayhew DR. Report to Transport Canada TP11549E. Ottawa: Transport Canada, Road Safety and Motor Vehicle Regulation; 1991. Diagnostic Assessment of Problem Drivers: Review of Factors Associated with Risky and Problem Driving. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lapham SC, C’de Baca J, McMillan GP, Hunt WC. Accuracy of alcohol diagnosis among DWI offenders referred for screening. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lapham SC, C’de Baca J, Chang I, Hunt WC, Berger LR. Are drunk-driving offenders referred for screening accurately reporting their drug use? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:243–253. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fell JC. Repeat DWI Offenders in the United States. Vol. 85. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic Tech:Technology Transfer Series; 1995. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beitel GA, Sharp MC, Glauz WD. Probability of arrest while driving under the influence of alcohol. Inj Prev. 2000;6:158–161. doi: 10.1136/ip.6.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavaiola AA, Strohmetz DB, Abreo SD. Characteristics of DUI recidivists: a 12-year follow-up study of first time DUI offenders. Addict Behav. 2007;32:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCord J. Drunken drivers in longitudinal perspective. J Stud Alcohol. 1984;45:316–320. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1984.45.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapham SC, Smith E, C’de Baca J, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among persons convicted of driving while impaired. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:943–949. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity or 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lapham SC, Skipper BJ, Simpson GL. A prospective study of the utility of standardized instruments in predicting recidivism among first DWI offenders. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:524–530. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perrine MW, Peck RC, Fell JC. Epidemiologic Perspectives on Drunk Driving. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 1989. pp. 35–76. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lapham S, Baum G, Skipper B, Chang I. Attrition in a follow-up study of driving while impaired offenders: Who is lost? Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35:464–470. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Ratcliff KS, Seyfried W. Validity of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version II: DSM-III diagnoses. Psychol Med. 1982;12:855–870. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI): A critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.SAS Institute I. SAS 9.1.3 Language Reference: Concepts. Third Edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. Second edition. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lapham SC, Skipper B. Current drinking and driving over the limit 15 years after a first DWI conviction. 2011 In review. [Google Scholar]

- 29.APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am Psychol. 2006;61:271–285. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dennis M, Scott CK. Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2007;4:45–55. doi: 10.1151/ascp074145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, Roman PM. Adoption and implementation of medications in addiction treatment programs. J Addict Med. 2011;5:21–27. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d41ddb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lapham SC, McMillan GP. Open-label pilot study of extended-release naltrexone to reduce drinking and driving among repeat offenders. J Addict Med. 2010;4 doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181eb3b89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lapham S, Forman R, Alexander M, Illeperuma A, Bohn MJ. The effects of extended-release naltrexone on holiday drinking in alcohol-dependent patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S.Department of Transportation NHTSA. Traffic Safety Facts: Fatalities Related to Alcohol-impaired Driving During the Christmas and New Year’s Day Holiday Periods. NHTSA’s National Center for Statistics and Analysis; 2007. [October 30, 2009]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLellan TA, Lewis D, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Is drug dependence a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance and outcome evaluation. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards G, Taylor C. Drinking problems, the matching hypothesis and a conclusion revised. Addiction. 1994;89:609–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards G, Taylor C. A test of the matching hypothesis: alcohol dependence, intensity of treatment, and 12-month outcome. Addiction. 1994;89:553–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moos RH, Finney JW. Alcoholism Treatment: Context, Process, and Outcome. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mann K, Schafer DR, Langle G, Ackermann K, Croissant B. The long-term course of alcoholism, 5, 10 and 16 years after treatment. Addiction. 2005;100:797–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller L. Predicting relapse and recovery in alcoholism and addiction: Neuropsychology, personality,and cognitive style. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1991;8:277–291. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(91)90051-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKay JR, Weiss RV. A review of temporal effects and outcome predictors in substance abuse treatment studies with long-term follow-ups. Preliminary results and methodological issues. Eval Rev. 2001;25:113–161. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grant BF. DSM-IV, DSM-III-R, and ICD-10 alcohol and drug abuse/harmful use and dependence, United States, 1992: A nosological comparison. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1481–1488. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Day E, Best D. Natural history of substance-related problems. Psychiatry. 2007;6:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lapham SC, C’de Baca J, Kapitula LR, McMillan GP, Skipper BJ, Lapidus J. Psychiatric disorders in a sample of repeat impaired-driving offenders. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;64:707–713. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.LaPlante DA, Nelson SE, Odegaard SS, LaBrie RA, Shaffer HJ. Substance and psychiatric disorders among men and women repeat driving under the influence offenders who accept a treatment-sentencing option. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:209–217. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCutcheon VV, Heath AC, Edenberg HJ, et al. Alcohol criteria endorsement and psychiatric and drug use disorders among DUI offenders: greater severity among women and multiple offenders. Addict Behav. 2009;34:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cotter RB, Burke JD, Loeber R, Mutchka J. Predictors of contact difficulty and refusal in a longitudinal study. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2005;15:126–137. doi: 10.1002/cbm.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jamieson E, Taylor PJ. Follow-up of serious offender patients in the community: multiple methods of tracing. Int J Meth Psychiatr Res. 2002;11:112–124. doi: 10.1002/mpr.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farrington DP. Longitudinal research strategies: advantages, problems, and prospects. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:369–374. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brame R, Piquero Ar. Selective attrition and the age-crime relationship. J Quant Criminol. 2003;19:107–127. [Google Scholar]

- 52.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. pp. 175–391. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.