Abstract

Each year, an increasing number of children are born through surrogacy and thus lack a genetic and/or gestational link with their mother. This study examined the impact of surrogacy on mother-child relationships and children’s psychological adjustment. Assessments of maternal positivity, maternal negativity, mother-child interaction and child adjustment were administered to 32 surrogacy, 32 egg donation and 54 natural conception families with a 7-year-old child. No differences were found for maternal negativity, maternal positivity or child adjustment, although the surrogacy and egg donation families showed less positive mother-child interaction than the natural conception families. The findings suggest that both surrogacy and egg donation families function well in the early school years.

Keywords: surrogacy, egg donation, parent-child relationship, psychological adjustment

Each year an increasing number of children are born who lack a genetic and/or gestational link with their mother. Since the birth in 1983 of the first child conceived using a donated egg (Lutjen et al, 1984; Trounson, Leeton, Besanka, Wood, & Conti, 1983), it has been possible for women to become pregnant with a child to whom they are genetically unrelated. The most recent figures show that the number of assisted reproduction cycles involving egg donation in the United States increased from around 2000 in 1996 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006) to more than 17,000 in 2007 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007), a number that is increasing exponentially each year. Although children conceived by egg donation are genetically unrelated to their mother, they are born to the mother who will raise them. In the case of surrogacy, where one woman bears a child for another woman, the mother who parents the child and the mother who gives birth to the child are not the same.

There are two types of surrogacy: traditional surrogacy, in which the surrogate mother and the commissioning father are the genetic parents of the child, and gestational surrogacy, in which the commissioning mother and father are the genetic parents. Although reports of traditional surrogacy date back to biblical times, there has been a rise in this route to parenthood in recent decades alongside the increasing use of assisted reproductive technologies. With traditional surrogacy, conception usually takes place through the artificial insemination of the surrogate mother with the commissioning father’s sperm. Gestational surrogacy only became possible following the introduction of in vitro fertilization (IVF) in 1978. This involves fertilization of the surrogate mother’s egg with the commissioning father’s sperm in the laboratory and the transfer of the resulting embryo to the surrogate mother’s womb. Thus, children born through gestational surrogacy lack a gestational link with their mother, and children born through traditional surrogacy lack both a gestational and a genetic link. The growth in the practice of surrogacy allows the role of biological ties in parenting and child development to be examined in novel ways.

In the absence of any empirical studies of the functioning of surrogacy families, the present investigation, in which surrogacy families are compared with egg donation and natural conception families, was initiated to address concerns that had been raised regarding the potentially adverse consequences of surrogacy for parents and children, and is the first investigation of surrogacy families in which in-depth data on family functioning and child development have been obtained from infancy onward. The egg donation families were included as a comparison group in addition to the natural conception families to control for the experience of female infertility and the involvement of a third-party in the child’s conception. Phase 1 was conducted when the children were 1 year old (Golombok, Murray, Jadva, MacCallum & Lycett, 2004), Phase 2 was conducted at age 2 (Golombok, MacCallum, Murray, Lycett & Jadva, 2006a) and Phase 3 was conducted at age 3 (Golombok, Murray, Jadva, Lycett, MacCallum & Rust, 2006b).

At the age 1 assessment, standardized interview and questionnaire measures of the psychological well-being of the parents and the quality of parent-child relationships were administered to each family at home. The differences that were identified indicated greater parental psychological well-being and greater adaptation to parenthood by mothers and fathers of children born through surrogacy than by the natural conception parents (MacCallum, Lycett, Murray, Jadva & Golombok, 2003; Golombok et al., 2004).

The families were next assessed at the time of the child’s 2nd birthday. The Parent Development Interview (Slade, Belsky, Aber & Phelps, 1999) was used to provide an in-depth assessment of the nature of the emotional bond between the mother and the child. The Parent Development Interview examines parents’ thoughts and feelings regarding their relationship with their child, and produces variables that specifically relate to the emotional experience of the parent such as joy and anger. The children’s cognitive development and psychological adjustment respectively were assessed using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development 2nd Edition (Bayley, 1993) and the Brief Infant Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Irwin, Wachtel & Cicchetti, 2004). In comparison with the natural conception families, the surrogacy mothers showed more positive parent-child relationships (higher levels of joy and competence, and lower levels of anger and guilt) than mothers with a naturally conceived child, and the surrogacy fathers reported lower levels of parenting stress than their natural conception counterparts (Golombok et al., 2006a). Regarding the children, no group differences were found for either cognitive development or psychological adjustment (Golombok et al., 2006a).

Assessments of family relationships and child development were again conducted when the child reached 3 years of age (Golombok et al, 2006b). The differences found between family types reflected higher levels of warmth and interaction between mothers and children in surrogacy families than in families with a naturally conceived child. Thus the findings from the preschool phases of the study indicated more positive parent-child relationships in surrogacy than in natural conception families. At all three phases, the egg donation families were more similar to the surrogacy than the natural conception families.

No data are available on the functioning of surrogacy families beyond the pre-school years. However, there is a well-established body of research on adoptive families who are similar to surrogacy families in that social motherhood is dissociated from biological motherhood. Although early research on adoptive families indicated increased rates of child psychological problems in comparison with non-adoptive families (Palacios & Brodzinsky, 2010), recent meta-analytic studies have demonstrated that the higher incidence of behavior problems shown by adopted children in comparison with their non-adopted counterparts is small in magnitude, with the large majority functioning within the normal range (Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2005), and that there are no differences between adopted and non-adopted children in self-esteem (Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2007). Moreover, studies that have examined factors associated with adjustment problems indicate that the difficulties shown by adopted children are largely related to factors that pre-date their adoption, such as prenatal exposure to toxins or hazards, the experience of abusive or neglectful parenting, or of multiple caretakers, in the years before the adoption took place (Dozier & Rutter, 2008; Palacios & Brodzinsky, 2010).

With respect to parenting in adoptive families, parents’ openness with adopted children about their origins has been found to be associated with positive parent-child relationships and children’s psychological adjustment (Kirk, 1964; Brodzinsky, 2005 & 2006; Grotevant, Perry & McRoy, 2005; Grotevant, 2007). Whereas Grotevant and colleagues have focused on open adoption arrangements where there is contact between the adoptive family and the birth family (which may range from occasional letters to face-to-face contact), Brodzinsky has emphasized open communication about adoption between the adoptive parents and the child irrespective of whether an open adoption arrangement is in place. Both agree that it is important for children to be given developmentally appropriate information about their adoption and to feel free to discuss issues relating to their adoption with their adoptive parents as they arise (Brodzinsky & Pinderhughes, 2002; Wrobel, Kohler, Grotevant & McRoy, 2003).

Research on non-traditional family forms enables the impact of different family structures, and the relative influence of family structure and family processes, on family functioning and children’s adjustment to be examined (Chan, Raboy, & Patterson, 1998; Dunn, Deater-Deckard, Pickering, O’Connor, Golding, & The ALSPAC Study Team, 1998; Golombok, 2000; Lansford, Ceballo, Abbey, & Stewart, 2001; Biblarz & Stacey, 2010). Whereas studies of adoptive families allow the investigation of the impact of the absence of both a gestational and genetic relationship between the parents and the child, studies of families with children conceived by egg, sperm or embryo donation allow the absence of a genetic relationship only between one or both parents and the child to be explored. Other examples include investigations of families with same-sex parents which shed light on the influence of parental sexual orientation; comparisons between single-mother and single-father families, or between two-parent lesbian mother families and two-parent gay father families, to provide information about the role of parental gender; and comparisons between single-parent and two-parent families with parents of the same gender to increase understanding of the impact of number of parents in the family. Although these “natural experiments” are not free of methodological problems, they do allow the separation of factors that in traditional families occur together (Rutter, Pickles, Murray & Eaves, 2001; Rutter, 2007).

The findings from this growing body of research on non-traditional families suggest that family processes such as warmth, communication and conflict are better predictors of children’s adjustment than is family structure. In relation to adoptive families, Lansford, Ceballo, Abbey, & Stewart (2001) found that family processes were more important than family structure for psychological well-being and the quality of family relationships in a study of adoptive, two-parent biological, single-mother, stepfather and stepmother households. Similarly, in a study of lesbian, gay and heterosexual adoptive families, no differences in parenting or child adjustment were found according to parental sexual orientation whereas family process variables such as parenting stress and parenting behaviors were found to be significantly associated with children’s psychological adjustment (Farr, Forsell, & Patterson, 2010).

In the earlier phases of the present study, the children were too young to be fully aware of the circumstances of their birth. This paper focused on the quality of mother-child relationships and children’s psychological adjustment at Phase 4 when the children were 7 years old, the age by which most adopted children have begun to understand the meaning and implications of adoption (Brodzinsky, Singer & Braff, 1984; Brodzinsky, Schechter & Brodzinsky, 1986; Brodzinsky & Pinderhughes, 2002). From the literature on adoptive families showing that most adopted children function within the normal range, the surrogacy families were not expected to differ from the other family types, especially as children born through surrogacy are less likely than adopted children to be exposed to either prenatal risk factors or adverse early circumstances, and parents in families created through surrogacy are generally open with their children about the nature of their birth. The growing body of research on other non-traditional family forms indicating that family structure in itself does not have an adverse effect on family functioning similarly led to the expectation that the surrogacy families would not differ from the egg donation or natural conception comparison groups. However, findings from the pre-school phases of the study predicted more positive mother-child relationships in surrogacy than in natural conception families.

Methods

Participants

At Phase 3 of the study, parents were asked for permission to contact them again for follow-up (see Golombok et al., 2004 for details of the initial recruitment of families to the study). Those who agreed were approached by telephone or letter as close as possible to the child’s 7th birthday.

The present phase of the study involved 32 families with a child born through surrogacy (21 [66%] by traditional surrogacy and 11 [34%] by gestational surrogacy) and comparison groups of 32 families with a child conceived by egg donation and 54 families with a naturally conceived child, representing 94%, 78% and 81% respectively of the number of surrogacy, egg donation and naturally conceived families seen at Phase III. The majority of those who did not participate at age 7 could not be traced or had moved abroad. Ninety-one percent of parents (n=107) were still married or cohabiting at the time of the study.

As shown in Table 1, there were similar proportions of boys and girls in each family type. A one-way ANOVA showed that the age of the child differed significantly between groups, F (2,115) = 7.25, p < .01, reflecting the slightly older age of the natural conception children (mean = 91.57 months) than the surrogacy (mean = 89.06 months) and egg donation (mean = 88.91 months) children. A significant difference was also found for mother’s age, F (2,115) = 13.35, p < .001, with older egg donation (mean = 47.13 years) and surrogacy (mean = 45.75 years) mothers than natural conception (42.09 years) mothers.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic information by family type

| Natural conception | Egg donation | Surrogacy | F | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age of child (months) | 91.57 | 3.85 | 88.91 | 3.29 | 89.06 | 3.77 | 7.25 | < .01 |

| Age of mother (years) | 42.09 | 3.06 | 47.13 | 6.01 | 45.75 | 5.38 | 13.35 | < .001 |

| Child’s sex | N | % | n | % | n | % | χ 2 | p |

| Boy | 26 | 48% | 20 | 63% | 14 | 44% | 2.54 (2) | ns. |

| Girl | 28 | 52% | 12 | 37% | 18 | 56% | ||

| Social class | ||||||||

| Professional | 28 | 52% | 14 | 44% | 14 | 44% | 11.12 (4) | < .05 |

| Managerial / technical | 25 | 46% | 10 | 31% | 13 | 41% | ||

| Skilled / non-manual | 1 | 2% | 8 | 25% | 5 | 15% | ||

| Number of siblings | ||||||||

| None | 3 | 6% | 14 | 44% | 9 | 28% | 20.22 (4) | < .001 |

| One | 45 | 83% | 13 | 41% | 19 | 59% | ||

| Two | 6 | 11% | 5 | 15% | 4 | 13% | ||

Social class was assessed by the occupation of the parent with the highest ranking position according to a modified version of the United Kingdom Registrar General’s classification (OPCS and Employment Department Group, 1991). Occupational classifications ranged from 1 (professional) through 2 (managerial/technical) to 3 (skilled/non-manual). The family types differed with respect to social class, χ2 (4) = 11.12, p < .05, with a lower proportion of surrogacy and egg donation families than natural conception families in higher ranking occupations. There was also a significant difference between family types for number of siblings, χ2 (4) = 20.22, p < .001, reflecting a lower proportion of surrogacy and egg donation families than natural conception families with siblings.

In the surrogacy families, 13 (41%) of surrogate mothers were known, and 19 (59%) were unknown, by the commissioning parents prior to the surrogacy arrangement. Nineteen (56%) of the families had seen the surrogate mother in the past year, with 9 (28%) of the children having seen the surrogate mother at least once per month. The relationship between the mother and the surrogate mother was reported to be harmonious by all but one of the mothers who remained in contact.

Procedure

One of three psychologists trained in the study techniques (LB, PC & JR) visited the families at home. Written informed consent to participate in the investigation was obtained from the mother and verbal assent was obtained from the child. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the University of Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee. The mother was administered a standardized interview that lasted approximately 1 hour and was digitally recorded. As data were obtained by interview on issues relating to the child’s conception, it was not possible for interviewers to be “blind” to family type. However, the section of the interview on the child’s psychological adjustment was rated by a child psychologist who was unaware of the method of the child’s conception. Mother-child dyads (n=98) also participated in a video recorded observational task that lasted 5-10 minutes. In addition, 108 of the mothers and 87 of the children’s teachers were administered a questionnaire designed to assess the children’s psychological adjustment. Written informed consent was obtained from the teachers.

Measures

Mother-child relationship

Interview with mother

The mothers were interviewed using an adaptation of an investigator-based interview designed to assess quality of parenting (Quinton & Rutter, 1988). Rather than using self-report data which relies on the mother’s understanding of what is being assessed, the interview employs a standardized approach to defining and coding the mother’s responses to the interview questions. This interview has been validated against observational ratings of mother-child relationships in the home, demonstrating a high level of agreement between global ratings of the quality of parenting by interviewers and observers. Detailed accounts were obtained of the child’s behavior and the mother’s response to it, with reference to the child’s progress at school, peer adjustment, and relationships within the family unit. Particular attention was paid to mother-child interactions relating to issues of warmth and control. A relatively flexible style of questioning was used to elicit sufficient information from the mother in order that each variable could be rated by the researcher according to a detailed, standardized coding scheme described in an accompanying manual. The researchers had all been trained in the administration and coding of the interview and regular meetings were held throughout the study to minimize rater discrepancy.

The following variables relating to the quality of the mother-child relationship were coded: (1) warmth was rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (low) through 1 (moderate) to 2 (high) taking account of the mother’s tone of voice and facial expressions when talking about the child in addition to the content of her verbal report of her relationship with her child (2) interaction was rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (low) through 1 (moderate) to 2 (high) and assessed the extent to which the mother and child spent time together, engaged in joint activities and enjoyed each other’s company (3) sensitivity was rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (low) through 1 (moderate) to 2 (high) and represented the mother’s ability to recognize and respond appropriately to her child’s needs (4) aggression was rated on a 3-point scale from 0 (none) through 1 (mild) to 2 (moderate) and measured how the mother reacted to the child in a situation of conflict (5) criticism assessed the degree of maternal criticism of the child on a 3-point scale from 0 (none) through 1 (minor) to 2 (moderate) (6) level of battle assessed the level of mother-child conflict on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (none) through 1 (minor) to 2 (moderate/major), and (7) frequency of battle assessed the frequency of mother-child conflict from 0 (never/rarely) through 1 (occasional) to 2 (frequent). Forty-seven randomly selected interviews were coded by a second interviewer who was unaware of family type and intra-class correlation coefficients for these variables were found to range from 0.50 to 0.80.

Parent-child observation

The Etch-A-Sketch task (Stevenson-Hinde & Shouldice, 1995) was used to obtain an observational assessment of mother-child interaction. This measure was chosen because it was age-appropriate, could be rated “blind” to family type, and could be taken into the family home. The Etch-A-Sketch is a drawing tool with two dials that allow one person to draw vertically and the other to draw horizontally. The mother and child were asked to copy a picture of a house, each using one dial only, with clear instructions not to use the other dial. The session was video recorded and coded using the Parent-Child Interaction System [PARCHISY] (Deater-Deckard & O’Connor, 2000; Deater-Deckard & Petrill, 2004; Deater-Deckard, Pylas & Petrill, 1997) to assess the construct of mutuality, i.e. the extent to which the mother and child engaged in positive dyadic interaction characterized by warmth, mutual responsiveness and cooperation (Kochanska, 1997). The following variables were rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (no instances) to 7 (constant, throughout interaction): (1) Mother’s responsiveness to child assessed the extent to which the mother responded immediately and contingently to the child’s comments, questions or behaviors (2) Child’s responsiveness to mother assessed the extent to which the child responded immediately and contingently to the mother’s comments, questions or behaviors (3) Dyadic reciprocity assessed the degree to which the dyad showed shared positive affect, eye contact and a “turn-taking” (conversation like) quality of interaction, and (4) Dyadic cooperation assessed the degree of agreement about whether and how to proceed with the task. Forty-seven randomly selected interviews were coded by two interviewers who were unaware of family type and intra-class correlation coefficients for these variables were found to range from 0.64 to 0.85.

Child psychological adjustment

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

The presence of child psychological problems was assessed with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [SDQ] (Goodman, 1994 & 1997) administered to the mother. The SDQ produces an overall score of the child’s adjustment with scores of 13 or below classified as within the normal range, scores of 14-16 classified as borderline and scores of 17 or above classified as abnormal, i.e. indicating psychological disorder.

An independent assessment of children’s psychological adjustment was obtained by administering the SDQ to teachers. This questionnaire has been designed for completion by teachers as well as parents. Following permission from the mother, the questionnaire was mailed to the child’s teacher with an enclosed stamped addressed envelope for return to the researcher. Teachers were informed by covering letter that their responses to the questionnaire would not be reported back to the child’s family or school. For teachers’ questionnaires, scores of 11 or below are classified as within the normal range, scores of 12-15 are classified as borderline and scores of 16 or above are classified as abnormal.

The SDQ has been shown to have good inter-rater reliability, with correlations between parent and teacher total scores reported to be 0.62. Evidence for validity comes from the high correlations between the total score of the SDQ and the total score of the Rutter Parent Questionnaire (Rutter, Tizard & Whitmore, 1970) and the Rutter Teacher Questionnaire (Rutter, 1967), which were designed to assess child psychiatric disorder. In addition, the SDQ discriminates well between psychiatric and non-psychiatric samples (Goodman, 1994 & 1997).

Results

Mother-child relationship

Drawing on procedures adopted by Golombok, Readings, Blake, Casey, Mellish, Marks & Jadva (2011), multiple groups CFA was used to establish a model of observational ratings of mother-child mutuality and interview ratings of maternal positivity and maternal negativity in the three groups simultaneously (natural conception, egg donation, surrogacy). This model was used to address two hypotheses. First, that mean differences between groups would be observed in mother-child mutuality and maternal positivity and maternal negativity; specifically, that children who were conceived by surrogacy or egg donation would experience higher levels of mutuality and maternal positivity, and lower levels of maternal negativity, than naturally conceived children. Second, that these group differences would be independent of group differences in child’s age, mothers’ age, occupational status, and number of siblings.

MPlus 5 (Muthen and Muthen, 2007) was used to analyze sample variance-covariance matrices. Using the guidelines proposed by Brown (2006), good model fit was evaluated using the following criteria: chi-square non-significant, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .06, and comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥ .95. In addition, CFI and TLI values in the range .90-.95 indicated adequate model fit.

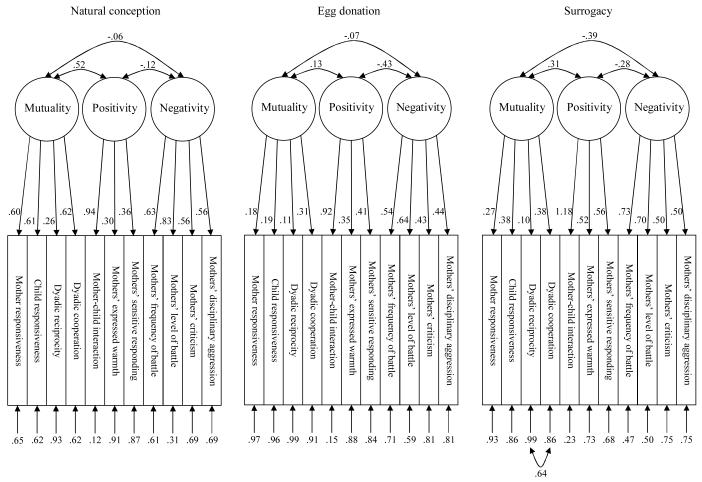

Using multiple-groups CFA, a model was specified in which observed indicators of mother’s and child’s responsiveness, dyadic reciprocity and dyadic cooperation loaded onto a latent variable of mother-child mutuality; mothers’ interview ratings of interaction, warmth and sensitivity loaded onto a latent variable of maternal positivity; and mothers’ interview ratings of frequency of battle, level of battle, criticism and aggression loaded onto a latent variable of maternal negativity. Multiple-groups CFA allowed the examination of whether these three latent variables showed similar measurement properties in all three groups. This was necessary in order to compare group means on the latent variables as these comparisons are only meaningful and interpretable if, at a given level of the latent variable, the values of the indicators are statistically equivalent in each group (i.e. both factor loadings and indicator intercepts are invariant).

The latent variables of mother-child mutuality, maternal positivity and maternal negativity were permitted to be correlated and the measurement model was simultaneously analyzed in three separate input matrices (one for each group). To optimize model fit, the residual variances of dyadic reciprocity and dyadic cooperation were allowed to be correlated within the surrogacy group. Factor loadings and indicator intercepts were constrained to equality across the three groups to examine the equivalence of measurement properties.

The model was over-identified (i.e. had sufficient degrees of freedom) with 154 df and fitted the data well: χ2 = 157.81, p = .40, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .97, TLI = .97. Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for the indicators and Figure 1 shows standardized parameter estimates, including factor covariances. All but one of the factor loadings were statistically significant: p < .05; the remaining loading was marginally significant: p = .10. These results suggested that the factor loadings and indicator intercepts of the indicators of mother-child mutuality, maternal positivity and maternal negativity were equivalent across all three groups (i.e. constraining these parameters to equality produced a good-fitting model). Therefore, it was concluded that the latent variables appeared to measure the same construct in the same way in each group, making subsequent comparisons of means meaningful and interpretable.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for indicators of mother-child mutuality, maternal positivity and maternal negativity, by family type

| Natural conception | Egg donation | Surrogacy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | ||

| Mother- child mutuality |

M responsiveness | 5.32 | .68 | 3-6 | 4.88 | .83 | 3-6 | 5.04 | .71 | 4-6 |

| C responsiveness | 4.82 | .92 | 2-6 | 4.36 | 1.08 | 2-6 | 4.48 | .73 | 3-6 | |

| D reciprocity | 1.80 | 1.01 | 0-5 | 1.44 | .82 | 0-3 | 1.87 | 1.29 | 0-5 | |

| D cooperation | 1.58 | 1.14 | 0-5 | .96 | .74 | 0-3 | 1.04 | .88 | 0-3 | |

| Maternal positivity |

M-C interaction | 1.46 | .57 | 0-2 | 1.19 | .64 | 0-2 | 1.28 | .77 | 0-2 |

| M expressed warmth | 1.06 | .79 | 0-2 | .91 | .69 | 0-2 | 1.03 | .74 | 0-2 | |

| M sensitive | 1.52 | .64 | 0-2 | 1.10 | .67 | 0-2 | 1.40 | .72 | 0-2 | |

| Maternal negativity |

M battle frequency | 1.26 | .76 | 0-2 | 1.38 | .75 | 0-2 | 1.16 | .69 | 0-2 |

| M battle level | 1.15 | .53 | 0-2 | 1.28 | .52 | 0-2 | 1.22 | .61 | 0-2 | |

| M criticism | 1.11 | .66 | 0-2 | 1.09 | .64 | 0-2 | 1.09 | .64 | 0-2 | |

| M aggression | 1.11 | .60 | 0-2 | 1.28 | .58 | 0-2 | 1.00 | .57 | 0-2 | |

Figure 1.

Multiple-group confirmatory factor analyses of mother-child mutuality, maternal positivity, and maternal negativity

Having established measurement invariance across groups in the latent variables, the model was applied to the first hypothesis regarding mean differences between the three groups. To compare these means, the multiple-groups CFA was extended in two ways. First, the within-group dispersion of the three latent variables was constrained to be equivalent across groups, to ensure latent means had a comparable scale across groups. Second, the means of each latent variable in the natural conception group were fixed to zero. This identified the natural conception group as the reference group, with the latent means in the egg donation and surrogacy groups representing their deviation from the reference group’s means. This model was over-identified with 160 df and fitted the data well: χ2 = 171.60, p = .25, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .92, TLI = .92. The additional constraint resulted in a significant reduction in model fit compared to the first model: χ2diff (6) = 13.79, p < .05. Inspection of the factor variances indicated that the variance for maternal positivity was much larger in the surrogacy group (.82) than in either the natural conception (.28) or egg donation (.34) groups. Therefore, the equal factor variances constraint was retained for the comparison of means to control for this group difference.

The mean comparisons revealed that, compared with the natural conception group, the surrogacy group had a significantly lower standardized mean for mother-child mutuality than the natural conception group: estimate = −.89, z = 2.38, p < .05; but not for maternal positivity or maternal negativity: estimate ≤ .32, z ≤ 1.26, p ≥ .21. The egg donation group had a significantly lower standardized mean for mother-child mutuality: estimate = −1.13, z = 2.91, p < .01; and a marginally significantly lower mean for maternal positivity: estimate = −.49, z = 1.70, p = .09; but not for maternal negativity: estimate = .04, z = .13, p = .89.

This model was run again to investigate differences between the surrogacy and egg donation groups. The latent means of the egg donation group were fixed to zero, making this the reference group. There were no significant differences between the egg donation and surrogacy groups’ standardized means for all three latent variables: estimate ≤ .36, z ≤ 1.17, p ≥ .24.

To address the second hypothesis, this multiple groups CFA was run with the family background variables covaried. There were significant group differences in child’s age: F (2, 115) = 7.25, p < .01, mothers’ age: F (2, 115) = 13.35, p < .001, highest occupational status: χ2 (4) = 11.12, p < .05, and number of siblings: χ2 (4) = 20.22, p < .001. Therefore, these four variables were covaried with the three latent variables to control for group differences in family background. This model was over-identified with 274 df, and provided a poor fit to the data: χ2 = 363.67, p < .01, RMSEA = .092, CFI = .61, TLI = .55. On inspection of the covariances with family background measures, only the association between maternal negativity and highest occupational status was significant. Therefore, the model was re-run with only this correlation included. This model was over-identified with 190 df, and model fit was adequate to good: χ2 = 201.12 p = .28, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .93, TLI = .92. The standardized covariance between maternal negativity and highest occupational status was significant in the natural conception group: estimate = −.48, z = 4.02, p < .01, but non-significant in the egg donation and surrogacy groups: estimate ≤ .32, z ≤ .97, p ≥ .33.

With this effect controlled, the surrogacy group still had a significantly lower standardized mean for mother-child mutuality than the natural conception group: estimate = −.89, z = 2.37, p < .05; but not for maternal positivity or negativity: estimate ≤ .31, z ≤ 1.28, p ≥ .20. The egg donation group still had a significantly lower standardized mean than the natural conception group for mother-child mutuality: estimate = −1.11, z = 2.88, p < .01; but not maternal positivity or maternal negativity: estimate ≤ .41, z ≤ 1.48, p ≥ .14. When the model was re-run to compare the egg donation and surrogacy groups, there were no significant differences on the standardized means for all three latent variables: estimate ≤ .33, z ≤ 1.09, p ≥ .28.

Child psychological adjustment

There were no significant differences in children’s total SDQ scores between family types for either mothers’ or teachers’ ratings. As shown in Table 3, the large majority of children obtained SDQ scores within the normal range. Of the 108 children whose mother completed the questionnaire, only 4 obtained a score within the borderline range (2 egg donation, 2 surrogacy) and 2 obtained a score within the abnormal range (both natural conception). Of the 87 children whose teacher completed the questionnaire, 7 obtained a borderline score (3 egg donation, 2 surrogacy, 2 natural conception) and 4 obtained an abnormal score (2 surrogacy, 2 natural conception). There was no significant group difference in the proportion of children classified as borderline or abnormal for mothers’: χ2 (4) = 5.90, p = .21, or teachers’: χ2 (4) = 3.48, p = .48, SDQ scores.

Table 3.

Number of children in the clinical range on mother- and teacher-rated SDQ, by family type

| NC | Egg donation | Surrogacy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | ||

| Mother SDQ |

Normal | 49 | 96 | 29 | 94 | 24 | 92 | 5.90 | ns. |

| Borderline | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| Abnormal | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Teacher SDQ |

Normal | 38 | 90 | 17 | 85 | 20 | 84 | 3.48 | . ns. |

| Borderline | 2 | 5 | 3 | 15 | 2 | 8 | |||

| Abnormal | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | |||

Discussion

In the present phase of the study there were no differences in maternal positivity between the surrogacy families and either the egg donation or the natural conception families. This is in contrast to the earlier phases when the surrogacy families were characterized by more positive mother-child relationships. At the age 1 assessment, greater warmth and enjoyment of the child were shown by mothers of children born through surrogacy in comparison with the natural conception mothers (Golombok et al, 2004), although this was accompanied by higher levels of emotional over-involvement. At age 2, the surrogacy mothers again showed more positive parent-child relationships, i.e. higher levels of joy and competence, and lower levels of anger and guilt (Golombok et al, 2006a), and at age 3 the surrogacy mothers showed higher levels of warmth and interaction than mothers with a naturally conceived child (Golombok et al, 2006b).

Neither were there differences for maternal negativity between the surrogacy families and either the egg donation families or the natural conception families. This finding is consistent with earlier phases of the study as mothers in surrogacy families did not show higher levels of anger or hostility toward their child than either the egg donation or natural conception families when the child was 2 years old (Golombok et al, 2006a). Thus it seems that the absence of a gestational link with the child is not associated with greater conflict and hostility between mothers and children in surrogacy families with a child of early school age.

There was a difference, however, between the surrogacy families and the natural conception families for the observational measure of mutuality, reflecting less positive mother-child interaction among the surrogacy than the natural conception mother-child dyads. The egg donation families also showed lower levels of mutuality than the natural conception families and did not differ from the surrogacy families on this measure. It is not known whether patterns of mother-child interaction differed between the assisted reproduction and the natural conception families in the earlier phases of the study as observational measures were not included in the preschool assessments.

Thus, the hypotheses derived from the earlier phases of the study that the surrogacy and the egg donation families would show higher levels of maternal positivity and lower levels of maternal negativity than the natural conception families were not supported by the findings of the present phase when the children were aged 7 years. However, the findings were in line with the prediction from previous research on adoptive and other non-traditional family forms that the surrogacy and egg donation families would not differ from the natural conception families on these measures. The unexpected finding of significantly lower levels of mutuality in both the surrogacy and the egg donation families than in the natural conception families suggests that the absence of a biological link between the mother and her child may be associated with less positive mother-child interaction at age 7. This finding may stem from the children’s increased understanding of surrogacy and egg donation at this age. Given that surrogacy and egg donation are similar to adoption with respect to the absence of a genetic and/or gestational link between the mother and the child, it may be relevant that it is around 5-6 years that children acquire an understanding of the meaning and implications of adoption (Brodzinsky et. al., 1984 & 1986; Brodzinsky & Pinderhughes, 2002). Lower levels of mutuality in surrogacy and egg donation families may also be related to the mothers’ experiences of assisted reproduction including the involvement of a third party in the birth of their child and unresolved feelings about their infertility, each of which may have a greater influence on mothers’ feelings and behavior toward their child following the child’s increased awareness of their origins. Mutuality is distinct from maternal positivity and negativity in that it reflects reciprocal interaction between the mother and the child rather than the behavior of the mother or child alone (Kochanska, 1997). Although it is not clear why mother-child interaction should be affected in surrogacy and egg donation families whereas maternal positivity and negativity are not, it should be noted that the more positive parenting found in the surrogacy and egg donation families when the children were in their preschool years was not longer apparent at age 7.

The lack of difference between the surrogacy families where the mother did not give birth to her child, and the egg donation families where she did, indicates that the absence of a genetic link rather than the absence of a gestational link may be associated with less positive interaction between the mother and her child. Although only two-thirds of the surrogacy arrangements involved the use of the surrogate mother’s egg and thus not all of the surrogacy children lacked a genetic as well as a gestational link with their mother, the similarity between the surrogacy and the egg donation families suggests that factors associated with the absence of a genetic relationship may have a greater role to play in the less positive mother-child interaction than factors associated with the absence of a gestational bond.

It is important to stress that the surrogacy and the egg donation families were not experiencing difficulties. They did not show higher levels of maternal negativity or lower levels of maternal positivity than the natural conception families. Instead, it seems that the absence of a biological link between mothers and their children may be associated with more subtle differences in patterns of mother-child interaction, i.e. in relation to responsiveness, reciprocity and cooperation. It should also be emphasized that the children were functioning well, with no differences identified according to family type by the mother or the child’s teacher. None of the surrogacy or egg donation children obtained a mothers’ SDQ score in the abnormal range, and only 2 of the surrogacy children and none of the egg donation children obtained a teachers’ SDQ score in the abnormal range, a lower proportion than the 8% expected from UK general population norms for children of this age (Meltzer, Gatward, Goodman, & Ford, 2000). This finding is in line with earlier phases of the study when nodifferences among family types were found for psychological adjustment in the preschool years (Golombok et. al., 2006a & b).

It could be argued that parenting difficulties and the presence of psychological problems in the children may have been played down by surrogacy or egg donation mothers who may wish to present their child in a favorable light either as a reaction to the stigma that is associated with these assisted reproductive procedures, or because they feel they must live up to high expectations of themselves as mothers given the difficulties they had to overcome in order to have a child. However, the teacher questionnaire provided an independent rating of the presence of emotional or behavioral problems in the children that confirmed the mothers’ reports. Moreover, the interview procedure, which involved lengthy and detailed questioning as well as the assessment of non-verbal aspects of the mothers’ responses, was designed to minimize socially desirable responding. Nevertheless, it is especially difficult to “fake good” with observational measures (Kerig, 2001). This may explain the discrepancy in the findings on the quality of the mother-child relationship between the interview and the observational measure. A particular advantage of the observational measure is that it allowed a detailed assessment of the quality of dynamic interactions between mothers and their children that cannot be captured by interview or self-report (Bakeman & Gottman, 1997; Hartman & Wood, 1990; Aspland & Gardner, 2003).

The study adopted a latent variable approach to examine differences in mother-child relationship quality between families who conceived naturally and those who used surrogacy or egg donation. This allowed the equivalence of the latent variables of mother-child mutuality, maternal positivity and maternal negativity to be tested in each group, making between-groups comparisons of means meaningful and interpretable. The group differences in mother-child mutuality appeared to be due to genuine differences in the underlying construct rather than to variation in construct measurement across the three groups. A further advantage of this approach is that it is particularly suited to the statistical analysis of the dichotomous and interval variables that formed the basis of the study.

If all of the surrogacy arrangements had involved the use of the surrogate mother’s egg, this would have allowed a direct comparison between families where both the genetic and gestational link between the mother and the child were absent and families where only the genetic link was missing. Such a comparison may have demonstrated an additional effect of the absence of a pregnancy. However, due to the scarcity of surrogacy families in the UK, with only around 40 children born through surrogacy each year in England and Wales (Brazier, Campbell & Golombok, 1998), it was decided to maximize the sample size by including families created by traditional as well as gestational surrogacy. A particular advantage of the UK sample is that all of the families are required by law to register with the General Register Office of the United Kingdom Office for National Statistics (ONS) and thus, with the aid of the ONS, we were able to recruit a highly representative sample of surrogacy families.

This is the first study worldwide to examine parent-child relationships and the psychological adjustment of children in surrogacy and egg donation families. Overall, the findings indicate that these families continue to function well in the early school years and are more similar than they are different. Surrogacy and egg donation provide a stricter paradigm for assessing the impact of the absence of a biological link between mothers and their children than adoption as they avoid the potentially confounding effects of adverse environmental factors such as neglectful or abusive parenting that are experienced by some children in the years prior to being adopted. Thus the findings of the present phase of the study add to the growing body of literature indicating that the quality of family relationships has a greater influence on children’s psychological wellbeing than the presence or absence of a biological connection between the mother and the child.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1HD051621 awarded to Susan Golombok.

This project was supported by grant number R01HD051621 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank the families who took part in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/dev

References

- Aspland H, Gardner F. Observational measures of parent child interaction. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2003;8:136–144. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Gottman J. Observing interaction: An introduction to sequential analysis. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baran A, Pannor R. Lethal Secrets. 2nd ed Amistad; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales II. The Psychological Corporation; London: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Biblarz T, Stacey J. How does the gender of parents matter? Journal of marriage and the Family. 2010;72:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Brazier M, Campbell A, Golombok S. Surrogacy: Review for Health Ministers of current arrangements for payments and regulation. Department of Health; London: 1998. (No. Cm. 4068) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan M, Carter A, Irwin J, Wachtel K, Cicchetti D. The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment: Screening for social-emotional problems and delays in competence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004 doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky DM. Reconceptualizing openness in adoption: Implications for theory, research and practice. In: Brodzinsky D, Palacios J, editors. Psychological issues in adoption: Research and practice. Praeger; Westport, CN: 2005. pp. 145–166. [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky D. Family structural openness and communication openness as predictors in the adjustment of adopted children. Adoption Quarterly. 2006;9:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky D, Pinderhughes E. Parenting and Child Development in Adoptive Families. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting. Vol. 1. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 279–312. [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky DM, Schechter D, Brodzinsky AB. Thinking about the family: Views of parents and children. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1986. Children’s knowledge of adoption: Developmental changes and implications for adjustment; pp. 205–232. [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky DM, Singer LM, Braff AM. Children’s understanding of adoption. Child Development. 1984;55:869–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. The Guildford press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports. Atlanta, Georgia: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports. Atlanta, Georgia: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chan RW, Raboy B, Patterson CJ. Psychosocial adjustment among children conceived via donor insemination by lesbian and heterosexual mothers. Child Development. 1998;69(2):443–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, O’Connor TG. Parent-child mutuality in early childhood: two behavioral genetic studies. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(5):561–570. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Petrill SA. Parent-child dyadic mutuality and child behavior problems: an investigation of gene-environment processes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(6):1171–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Pylas MV, Petrill SA. Parent-Child Interaction System (PARCHISY) Institute of Psychiatry; London, UK: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Rutter M, Cassidy J, Shaver J, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications. 2nd Edition Guilford Press; New York: 2008. Challenges to the Development of Attachment Relationships Faced by Young Children in Foster and Adoptive Care. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Deater-Deckard K, Pickering K, O’Connor TG, Golding J, The ALSPAC Study Team Children’s adjustment and prosocial behaviour in step-, single-parent, and non-stepfamily settings: Findings from a community study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39(8):1083–1095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr R, Forsell S, Patterson C. parenting and child development in adoptive families: Does parental sexual orientation matter? Applied Developmental Science. 2010;14(3):164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Golombok S. Parenting: What really counts? Routledge; London: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Golombok S, MacCallum F, Murray C, Lycett E, Jadva V. Surrogacy families: parental functioning, parent–child relationships and children’s psychological development at age 2. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006a;47(2):213–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombok S, Murray C, Jadva V, Lycett E, MacCallum F, Rust J. Non-genetic and non-gestational parenthood: consequences for parent-child relationships and the psychological well-being of mothers, fathers and children at age 3. Human Reproduction. 2006b;21(7):1918–1924. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombok S, Murray C, Jadva V, MacCallum F, Lycett E. Families Created through a Surrogacy Arrangement: Parent-child Relationships in the First Year of Life. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40(3):400–411. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombok S, Readings J, Blake L, Casey P, Mellish L, Marks A, Jadva V. Children conceived by gamete donation: The impact of openness about donor conception on psychological adjustment and parent-child relationships at age 7. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25(2):230–239. doi: 10.1037/a0022769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. A modified version of the Rutter Parent Questionnaire including extra items on children’s strengths: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35(8):1483–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant H. Openness in adoption: Re-thinking “family” in the US. In: Inhorn M, editor. Reproductive disruptions: Gender, technology and biopolitics in the new millennium. Berghahn Books; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Perry Y, McRoy RG. Openness in adoption: Outcomes for adolescents within their adoptive kinship networks. In: Brodzinsky D, Palacios J, editors. Psychological Issues in Adoption: Research and Practice. Praeger; Westport, CT: 2005. pp. 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann D, Wood D. Observational methods. In: Bellack A, Hersen M, Kazdin A, editors. International handbook of behavior modification and therapy. Plenum; New York: 1990. pp. 107–138. [Google Scholar]

- Juffer F, van IJzendoorn MH. behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: A meta-analysis. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:2501–2515. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juffer F, van IJzendoorn MH. Adoptees do not lack self-esteem: A meta-analysis of studies on self-esteem of transracial, international, and domestic adoptees. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:1067–1083. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK, editor. Introduction and overviews: Conceptual issues in family observational research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk HD. Shared fate: A theory and method of adoptive relationships. Free Press; New York: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: implications for early socialization. Child Development. 1997;68(1):94–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford J, Ceballo R, Abbey A, Stewart A. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:840–851. [Google Scholar]

- Lutjen P, Trounson A, Leeton J, Findlay J, Wood C, Renou P. The establishment and maintenance of pregnancy using in vitro fertilization and embryo donation in a patient with primary ovarian failure. Nature. 1984;307(12):174–175. doi: 10.1038/307174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer H, Gatward R, Goodman R, Ford T. Mental health of children and adolescents in Great Britain. TSO; London: 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. MPlus. Version 5 Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- OPCS and Employment Department Group . Standard Classification of Occupations. HMSO; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios J, Brodzinsky D. Adoption research: Trends, topics, outcomes. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34(3):270–284. [Google Scholar]

- Quinton D, Rutter M. Parenting Breakdown: The making and breaking of intergenerational links. Avebury Gower Publishing; Aldershot, UK: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. A childrens’ behaviour questionnaire for completion by teachers: preliminary findings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1967;8:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1967.tb02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Proceeding from observed correlation to causal inference: The use of natural experiments. Psychological Science. 2007;2(4):377–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Pickles A, Eaves L. Testing hypotheses on specific environmental causal effects on behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(3):291–324. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Tizard J, Whitmore K. Education, health and behaviour. Longman; London: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Belsky J, Aber JL, Phelps JL. Mothers’ representations of their relationships with their toddlers: links to adult attachment and observed mothering. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(3):611–619. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson-Hinde J, Shouldice A. Maternal interactions and self reports related to attachment classifications at 4.5 years. Child Development. 1995;66:583–596. [Google Scholar]

- Trounson A, Leeton J, Besanka M, Wood C, Conti A. Pregnancy established in an infertile patient after transfer of a donated embryo fertilized in vitro. British Medical Journal. 1983;286(835-838) doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6368.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel G, Kohler J, Grotevant H, McRoy R. The Family Adoption Communication Model (FAC): Identifying pathways of adoption-related communication. Adoption Quarterly. 2003;7:53–84. [Google Scholar]