Abstract

While crystallographic structures of the R. etli pyruvate carboxylase (PC) holoenzyme revealed the location and probable positioning of the essential activator, Mg2+, and non-essential activator, acetyl-CoA, an understanding of how they affect catalysis remains unclear. The current steady-state kinetic investigation indicates that both acetyl-CoA and Mg2+ assist in coupling the MgATP-dependent carboxylation of biotin in the biotin carboxylase (BC) domain with pyruvate carboxylation in the carboxyl transferase (CT) domain. Initial velocity plots of free Mg2+ vs. pyruvate were nonlinear at low concentrations of Mg2+ and a nearly complete loss of coupling between the BC and CT domain reactions was observed in the absence of acetyl-CoA. Increasing concentrations of free Mg2+ also resulted in a decrease in the Ka for acetyl-CoA. Acetyl phosphate was determined to be a suitable phosphoryl donor for the catalytic phosphorylation of MgADP, while phosphonoacetate inhibited both the phosphorylation of MgADP by carbamoyl phosphate (Ki = 0.026 mM) and pyruvate carboxylation (Ki = 2.5 mM). In conjunction with crystal structures of T882A R. etli PC mutant cocrystallized with phosphonoacetate and MgADP, computational docking studies suggest that phosphonoacetate could coordinate to one of two Mg2+ metal centers in the BC domain active site. Based on the pH profiles, inhibition studies and initial velocity patterns, possible mechanisms for the activation, regulation and coordination of catalysis between the two spatially distinct active sites in pyruvate carboxylase from R. etli by acetyl-CoA and Mg2+ are described.

Pyruvate carboxylase (PC1; E.C 6.4.1.1) is an essential regulatory, anaplerotic enzyme which catalyzes the MgATP-dependent carboxylation of pyruvate by HCO3− to form oxaloacetate, MgADP and Pi (1). The oxaloacetate formed is either fed directly into the citric acid cycle where the intermediates are removed for various metabolic pathways including gluconeogenesis in liver (1), de novo fatty acid biosynthesis in adipose tissue, synthesis of neurotransmitters in the brain and glucose-induced insulin secretion in pancreatic islets (2). The significance of PC activity in intermediary metabolism and the importance of the regulation of this activity by allosteric activators, such as acetyl-CoA, and inhibitors, including L-aspartate, have been shown in recent studies where increased PC activity is linked to the pathogenesis of a variety of diseases. For example, a positive correlation between aberrant PC activity and the proliferation of tumor cells has been established through the 13C-isotopologue analysis of metabolites in cancer patients (3), while the enhanced PC gluconeogenic activity detected in the liver of type 2 diabetic patients is partly responsible for the overabundant production of glucose in the liver (4). An increase in the transcription levels and the activity of PC in both Listeria monocytogenes (5) and Staphylococcus aureus (6) have been correlated with intensified bacterial virulence.

The three individual functional domains of α4 pyruvate carboxylases, including PC from R. etli (RePC), are arranged on a single polypeptide chain (1), with the PC-catalyzed carboxylation of pyruvate occurring in two steps at spatially distinct active sites (Scheme 1). The concurrent deprotonation of HCO3− and cleavage of MgATP in the biotin carboxylase (BC) domain results in the formation of a carboxyphosphate intermediate, which reversibly decomposes into CO2 and PO43−. The biotin carboxyl carrier protein (BCCP) domain carries the biotin cofactor, which is covalently attached to Lys11192, between the BC and carboxyl transferase (CT) domains. PO43− migrates in the BC domain active site to position itself near the tethered biotin binding pocket (Scheme 2). Acting as an active site base, PO43− deprotonates biotin at the N1-postion to form the biotin enolate which then reacts with CO2 to produce carboxybiotin. Further details of the proposed catalytic mechanism of the BC domain are presented in the accompanying manuscript (7). The tethered carboxybiotin is then translocated to the CT domain active site on a neighboring polypeptide chain, via the movement of the BCCP domain (8), releasing MgADP and Pi from the BC domain active site. Enolization of pyruvate in the CT domain, promoted by coordination to the Lewis acid metal center in the active site, and proton transfer to the biotin enolate is facilitated by a strictly conserved Thr residue (9). CO2 then reacts with the nucleophilic enol-pyruvate intermediate, resulting in the formation of oxaloacetate.

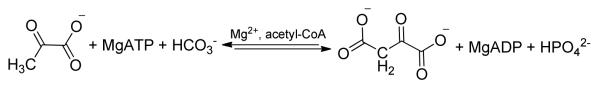

Scheme 1.

The overall reaction catalyzed by RePC.

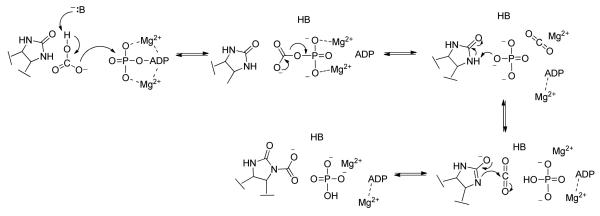

Scheme 2.

A generalized mechanism of the MgATP-dependent carboxylation of biotin in the BC domain. B is the general base required to deprotonate HCO3− .

While the chemical and kinetic mechanisms of pyruvate carboxylation catalyzed by α4 PCs from different organisms are expected to be similar, the regulation of the activity and sensitivity to inhibitors and activators, including acetyl-CoA and divalent cations, can vary depending on the physiological differences in the metabolism of the organisms from which the enzyme originates (10). Additionally, metabolic differences between R. etli, a strict aerobe (11), and S. aureus, a facultative anaerobe (12), may, in part, result in the substantial quaternary structural differences observed in the α4 PC holoenzymes (8, 13, 14). The inherent asymmetry of the RePC tetramer observed when ethyl-CoA is bound in the allosteric site (8) or when co-crystallized with either acetyl-CoA or the allosteric inhibitor, L-aspartate (13), alludes to the possible differential activation and regulation of RePC by acetyl-CoA compared to SaPC, which is symmetric even in the presence of acetyl-CoA (14). Interestingly, only two of the four allosteric active sites are occupied by ethyl-CoA in the R. etli holoenzyme structures while all four allosteric sites in SaPC contain the activator.

The structural differences between RePC and SaPC prompted, in part, the characterization of the acetyl-CoA and Mg2+ activation of RePC presented here. The current study examined the effects of acetyl-CoA and Mg2+ on the activities of the full forward and reverse reaction, as well as the partial reactions occurring at each active site. Initial velocity studies show that both Mg2+ and acetyl-CoA aid in coordinating the chemistry occurring in each of the domains such that MgATP-cleavage and biotin carboxylation in the BC domain are coupled to pyruvate carboxylation in the CT domain at saturating concentrations of pyruvate, Mg2+ and acetyl-CoA. Acetyl phosphate was found to be a suitable phosphoryl donor in the RePC catalyzed phosphorylation of MgADP. pH profiles and inhibition studies of the pyruvate carboxylation and MgADP phosphorylation reactions with phosphonoacetate give new insight into the reactions of the BC domain of wild-type RePC. These studies, along with the new structural description of RePC containing BCCP-biotin in the BC domain (13) and the rigorous site-directed mutagenesis study focusing on the BC domain active site of RePC (7) presented in the accompanying manuscripts allow for a more comprehensive picture of the complex regulation and activation of pyruvate carboxylation catalyzed by RePC.

Materials and Methods

Materials

IPTG, biotin, NADP, NADH, ampicillin and chloramphenicol were purchased from Research Products International Corp. (RPI). Ni2+-Profinity IMAC resin was obtained from Bio-Rad. The Pierce BCA Assay kit was purchased from Thermo Scientific and the EnzChek Phosphate Assay kit was purchased from Invitrogen. All other materials were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and of the highest purity available.

Methods

Mutagenesis, overexpression and purification of protein

Preparation and purification of the wild-type and T882A and K1119Q RePC mutants were performed as previously described (9). The proteins were purified using Ni2+-affinity chromatography, concentrated to approximately 2-6 mg/mL and used without further purification. The nearly complete (> 98%) biotinylation of the wild-type and the T882A RePC mutant and lack of biotinylation in the K1119Q mutant was confirmed via an avidin binding gel-shift assay (9).

Enzymatic assays

The coupled assay systems used to determine the initial rates of the overall forward and reverse reactions, as well as the partial reactions of the individual domains are similar to those described previously (9) and further detailed in the accompanying manuscript (7). Specific reaction conditions are discussed below. In most cases, the mixed buffer system (50 mM Bis-Tris, 25 mM Tricine and 25 mM glycine) was used as a replacement for the 100 mM Tricine buffer used previously.

Pyruvate carboxylation activity and determination of initial velocity patterns

Pyruvate carboxylation activity was measured using the malate dehydrogenase coupled assay in reaction volumes of 1 mL (25° C, pH 7.5). Concentrations of MgATP stock solutions were determined via end-point analysis using the hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate coupled assay system, pyruvate was determined using lactate dehydrogenase, and HCO3− was determined using phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase/malate dehydrogenase. Initial velocity patterns were determined by measuring the initial rates of the overall reaction at various concentrations of one substrate or pseudo-substrate (Mg2+, MgATP, acetyl-CoA or pyruvate) at fixed concentrations of a second substrate. All other reaction components were held constant at saturating concentrations. For the determination of the patterns between free Mg2+ and MgATP, reactions contained 12 mM pyruvate, 15 mM HCO3−, MgCl2 (1.09-7.44 mM), MgATP (0.058-3.4 mM), 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA, 0.24 mM NADH and malate dehydrogenase (10 U). For reactions where pyruvate (0.18-13 mM) was varied at fixed concentrations of free Mg2+ (1.0-7.8 mM), 25 mM HCO3−, 2.5 mM MgATP and 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA were held constant. Similarly, when acetyl-CoA (0.0-0.3 mM) was varied at fixed Mg2+ (0.5-3.0 mM), 12 mM pyruvate, 15 mM HCO3− and 2.5 mM MgATP were held constant.

To accurately determine the Km for HCO3− in the pyruvate carboxylation reaction, buffers and stock solutions of the reaction cocktails were sparged with CO2-free N2 at pH 7.5 overnight to remove any endogenous CO2. To prepare the HCO3− stock solutions, NaHCO3 was added to round-bottom flasks equipped with a stopcock arm and rubber septum. The flasks were sealed and flushed with CO2-free N2 for 1 hr prior to the addition of distilled water via syringe. 1.5 mL cuvettes were stoppered with rubber septa and flushed with N2 for 5-10 min prior to the addition of the sparged reaction components. Control reactions indicated that the small amount of CO2 introduced into the system from the enzyme solutions had no effect on the rates. The kcat and kcat/Km for HCO3− were determined at pH 7.5 in 1 mL reaction volumes containing HCO3− (0.35-20 mM), 12 mM pyruvate, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 3.0 mM MgATP, 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA, 0.24 mM NADH and malate dehydrogenase (10 U). The dependence of kcat and kcat/Km MgATP on pH in the full forward reaction was determined in assays similar to those above where MgATP was the variable substrate (0.05-3.2 mM) in 1 mL total reaction volumes. The mixed buffer system used for all the kinetic studies (50 mM Bis-Tris, 25 mM Tricine, 25 mM glycine) effectively buffered the reactions throughout the range of pH values examined while maintaining a constant ionic strength (15). All other substrates and activators were held at fixed, saturating concentrations and kcat and kcat/Km values were determined at each pH (6.7-8.6). 25 mM of HCO3− was added to the reactions. While the actual concentration of HCO3− in the reaction mixtures will vary with pH, the amount of HCO3− present is still sufficient to saturate the enzyme. The initial rates of the wild-type-catalyzed carboxylation of pyruvate were also determined in the presence of fixed concentrations of phosphonoacetate (0-6.0 mM) and varying concentrations of MgATP (0.16-2.0 mM). All reactions (25° C, 1 mL) were initiated with the addition of wild-type RePC (5-25 μg) and contained 50 mM Bis-Tris, 25 mM Tricine, 25 mM glycine (pH 7.5), 25 mM HCO3−, 12 mM pyruvate, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA, 0.24 mM NADH and malate dehydrogenase (10 U).

Activities of the full reverse reaction

The initial rates of the full reverse reaction were determined using the hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase coupled assay system. The kcat and kcat/Km were determined by varying MgADP (0.05-1.0 mM). The 3 mL reactions (pH 7.5, 25° C) contained 7.0 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM phosphate, 1.0 mM oxaloacetate, 0.3 mM glucose, 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA, 0.24 mM NADP+, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (5 U) and hexokinase (1 U). Specific activities were also determined in the presence and absence of acetyl-CoA, in triplicate, and the standard errors reported are the standard deviations of the three runs. The dependence of kcat and kcat/Km MgADP for the full reverse reaction on pH was also determined under analogous conditions at varying pH (6.0-8.5).

HCO3−-dependent ATPase activity in the absence of pyruvate

The EnzChek Phosphate (Invitrogen) assay system was used to determine the initial rates of Pi release. Initial rates were determined by monitoring the corresponding increase in absorbance at 360 nm due to the formation of 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methyl purine from the PNP-catalyzed phosphorylation of MESG by Pi. The extinction coefficient for 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methyl purine at 360 nm was determined to be 6300 cm−1 M−1 under conditions similar to those used for the RePC catalyzed reaction (50 mM Bis-Tris, 25 mM Tricine, 25 mM glycine, 20 mM HCO3−, pH 7.5, 25° C) and was used for all subsequent calculations. The kcat and kcat/Km MgATP for the wild-type RePC catalyzed MgATP-cleavage reaction was determined at 25° C in 1 mL total reaction volumes. Reactions contained 20 mM HCO3−, 5.0 mM MgCl2, MgATP (2.6-450 μM), 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA (unless otherwise indicated), 0.2 mM MESG and PNP (3 U).

Oxamate-induced decarboxylation of oxaloacetate

The specific activities of oxaloacetate decarboxylation in the presence of oxamate were monitored in the presence and absence of acetyl-CoA using the lactate dehydrogenase coupled assay. The 3 mL reactions contained 50 mM Bis-tris, 25 mM Tricine, 25 mM glycine (pH 7.5, 25° C), 1 mM oxamate, 0.95 mM oxaloacetate, 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA (unless otherwise indicated), 0.24 mM NADH and lactate dehydrogenase (10 U). Specific activities were determined in triplicate and standard errors reported are the standard deviations from the three trials.

Phosphorylation of MgADP using acetyl phosphate or carbamoyl phosphate as a phosphoryl donor

Carbamoyl phosphate and acetyl phosphate solutions were made just prior to use and kept on ice for the duration of the assay experiments. In order to remove contaminating nucleotides, a 0.2 M acetyl phosphate solution (85% purity) was acidified (pH 2.0) and stirred with activated charcoal for 30 min. After filtering, the solution was lyophilized and used for all subsequent experiments. The phosphorylating ability of the wild-type and the RePC mutants were determined by measuring the amount of MgATP production using the hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase coupled assay at various concentrations of either carbamoyl phosphate (1.0-20 mM) or acetyl phosphate (0.1-20 mM) and in the presence or absence of 10 mM free biotin. All assays were performed at 25° C and a total reaction volume of 1 mL. Reactions contained 3.5 mM MgADP, 7.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA (unless otherwise indicated), 0.4 mM glucose, 0.36 mM NADP, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (5 U) and hexokinase (1U). The effect of free Mg2+ on the initial rates of MgADP phosphorylation was also determined under similar reaction conditions as above with saturating concentrations of both MgADP (3.5 mM) and carbamoyl phosphate (20 mM) and varying concentrations of free Mg2+ (0-11 mM). The dependence of the kcat/Km for carbamoyl phosphate in the MgADP phosphorylation reaction on pH was also determined under equivalent conditions at varying pH (5.0-9.0), saturating Mg2+ (7.5 mM) and varied concentrations of carbamoyl phosphate (1.2-22.0 mM).

The inhibitory effects of phosphonoacetate with respect to carbamoyl phosphate for the MgADP phosphorylation reaction catalyzed by wild-type RePC were also examined using the same coupled assay system. Initial rates were determined at varying concentrations of carbamoyl phosphate (1.4-28 mM) and fixed concentrations of phosphonoacetate (0.33-20 mM). The 1 mL reactions (pH 7.5, 25° C) contained 7.5 mM MgCl2, 3.5 mM MgADP, 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA, 0.4 mM glucose, 0.36 mM NADP, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (5 U) and hexokinase (1U).

Determination of the coupling of MgATP-cleavage and pyruvate carboxylation in the presence and absence of acetyl-CoA

The initial rates of oxaloacetate formation and Pi release were determined at varying concentrations of pyruvate (0.09-5.25 mM) in order to determine the degree of coupling between the two reactions. Two 1 mL reactions containing 15 mM HCO3−, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM MgATP and 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA were prepared at each concentration of pyruvate (0.09-5.25 mM). 0.24 mM NADH and malate dehydrogenase (10 U) were added to reactions where oxaloacetate formation was being monitored, and the oxidation of NADH to NAD+ was followed at 340 nm. To reactions where Pi release was being determined, 3 U of PNP and 0.2 mM of MESG were added to the reaction mixtures prior to the addition of RePC (5-10 μg) and the background rate of MESG decomposition was monitored for approximately 2 min at 360 nm. Reactions were initiated with the addition of RePC and the corrected rate was used to determine the initial rates of Pi release. Similar reactions were used to determine the extent of coupling in the absence of acetyl-CoA.

Data Analysis

kcat and kcat/Km values were determined by fitting velocity versus substrate concentration data to eqn (1) using least-squares nonlinear regression, where A is the variable substrate concentration. All least-square fits were performed using FORTRAN programs (16) and best-fit lines were plotted using SigmaPlot v. 12.0, unless otherwise indicated.

| (1) |

The initial rates for pyruvate carboxylation determined at varying MgATP concentrations and fixed concentrations of Mg2+ were globally fitted to the equilibrium ordered eqn (2)

| (2) |

where Vmax is the maximal velocity at saturating concentrations of Mg2+ and MgATP, A is the concentration of Mg2+, B is the concentration of MgATP, Kia is the dissociation constant for Mg2+ and Kb is the Michaelis constant for MgATP. When MgATP was saturating and the concentration of pyruvate was varied at fixed concentrations of Mg2+ (0.7-3.0 mM), the resulting initial velocity plots were individually fitted to eqn (3)

| (3) |

where A is the concentration of pyruvate, V is the maximal velocity at saturating pyruvate and the fixed concentration of Mg2+ and b, c and d are kinetic constants associated with the overall rate of the reaction. Reciprocal plots for the initial rates of pyruvate carboxylation determined with varying pyruvate and 5 mM of free Mg2+ were linear and the data were fitted to eqn (1).

Sigmoidal rate of oxaloacetate formation vs. acetyl-CoA curves determined at varying concentrations of Mg2+ were individually fitted to eqn (4)

| (4) |

where v is the initial velocity determined, A is the concentration of acetyl-CoA, Vmax is the maximal velocity at saturating activator concentrations and n is the Hill coefficient.

kcat/Km and kcat pH profiles determined for the wild-type RePC catalyzed carboxylation of pyruvate with MgATP as the variable substrate were fitted to eqns (5) and (6), respectively,

| (5) |

| (6) |

where K1, K2 and K0 are the pKas determined from the fits of the pH profiles, H+ is the hydrogen ion concentrations corresponding to the pH, and C is a constant. Similarly, kcat/Km and kcat pH profiles for the full reverse reaction, where MgADP was the variable substrate, were both fitted to eqn (7)

| (7) |

The kcat/Km pH profile for the phosphorylation of MgADP by the variable substrate, carbamoyl phosphate, was fitted to eqn (8),

| (8) |

where K1 and K2 are the pKas determined from the fit of the kcat/Km pH profile, H+ is the hydrogen ion concentrations corresponding to the pH and YL and YH are the limiting kcat/Km values at low and high pH, respectively.

Inhibition of pyruvate carboxylation by phosphonoacetate with respect to MgATP was best described by the linear noncompetitive inhibition eqn (9)

| (9) |

where Vmax is the maximal velocity of the uninhibited reaction, A is the concentration of MgATP, I is the concentration of phosphonoacetate and Kis and Kii are the kinetic inhibition constants for the slope and intercept effects, respectively. Inhibition of the phosphorylation of MgADP using carbamoyl phosphate by phosphonoacetate was best described as hyperbolic noncompetitive inhibition (eqn 10)

| (10) |

where Vmax is the maximal velocity of the uninhibited reaction, A is the concentration of carbamoyl phosphate, I is the concentration of phosphonoacetate and Kid, Kis and Kii are the kinetic inhibition constants for the partial inhibition, slope and intercept effects, respectively.

Results

Kinetic characterization of wild-type PC from R. etli

kcat and kcat/Km values were determined for wild-type RePC for various substrates in the forward and reverse reactions in the presence of saturating concentrations of Mg2+ and acetyl-CoA (Table 1). The kinetic characterization revealed that the relative rates and catalytic efficiencies for the full reverse and partial forward and reverse reactions of the BC and CT domains were substantially lower than those determined for the wild-type-catalyzed carboxylation of pyruvate. The rate of oxaloacetate decarboxylation and subsequent formation of MgATP (full reverse reaction) was only 0.2% of the rate of pyruvate carboxylation, resulting in a nearly 400-fold difference between the kcat/Km determined for MgATP and MgADP in the forward and reverse reactions, respectively. The relative rate of oxaloacetate decarboxylation in the presence of oxamate was determined to be 2.0% of the full forward reaction. Compared to the rate of the full reverse reaction, saturating oxamate concentrations stimulated the rate of oxaloacetate decarboxylation in the CT domain 11-fold. Reactions occurring strictly in the BC domain also exhibited rates and catalytic efficiencies significantly lower than those for the full forward reaction. The HCO3−-dependent ATPase reaction was nearly 180-fold slower than the overall forward reaction. A considerable decrease in the observed Km for MgATP was accompanied by a 20-fold decrease in the kcat/Km MgATP for the MgATP-hydrolysis compared to the kcat/Km MgATP for pyruvate carboxylation. While the catalytic rate of MgADP phosphorylation by carbamoyl phosphate was equivalent to the rates of MgATP hydrolysis, acetyl phosphate was found to be a considerably slower substrate than carbamoyl phosphate (0.1% of the rate of pyruvate carboxylation). Interestingly, the rate of the partial reverse reaction of the BC domain using carbamoyl phosphate as a substrate was three-times greater than the rates of the full reverse reaction while the rate with acetyl phosphate as a substrate was 1.5 times less than the full reverse reaction. An accurate determination of the kcat/Km for HCO3− under CO2-free conditions with saturating concentrations of free Mg2+ (5 mM) revealed a relatively high Km for HCO3− of 10.8 ± 0.4 mM and a kcat of 700 ± 20 min−1 (Figure S1).

Table 1.

kcatand kcat/Kmvalues determined for the various reactions catalyzed by wild-type RePC a

| Variable Substrateb | kcat (min−1) |

Km (mM) |

kcat/Km (min−1 mM−1) |

% kcat of pyruvate carboxylation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyruvate carboxylation | MgATPc | 396 ± 10d | 0.145 ± 0.009 | 2670 ± 120 | (100) |

| HCO3− | 700 ± 20 | 10.8 ± 0.4 | 64.8 ± 0.9 | --- | |

| pyruvate | 440 ± 8d | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 2900 ± 150 | --- | |

| Full reverse reaction | MgADP | 0.835 ± 0.005 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 6.95 ± 0.002 | 0.2 |

| Oxamate-induced decarboxylation of oxaloacetate | NDe | 9.03 ± 0.04f | --- | ---- | 2.0 |

| HCO3−- dependent ATPase | MgATP | 2.58 ± 0.09 | 0.022 ± 0.003 | 115 ± 2 | 0.6 |

| ADP phosphorylation | Carbamoyl phosphate | 2.41 ± 0.01 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 0.6 |

| Acetyl phosphate | 0.56 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 1.70 ± 0.05 | 0.1 |

Kinetic parameters were determined from data fits to eqn (1).

Varied substrate indicated, all other substrates were held constant at saturating concentrations. Reaction conditions: 50 mM Bis-tris, 25 mM Tricine, 25 mM Glycine (pH 7.5), 25° C, 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA. For more detailed reaction conditions see Methods section.

kcat (min−1) and kcat/Km (min−1 mM−1) were determined from fits of the initial rates of pyruvate carboxylation at varying concentrations of MgATP and fixed Mg2+ to the equation for an equilibrium ordered pattern (eqn (2)) and the Kia Mg2+ = 1.2 ± 0.2 mM . All other kcat and kcat/Km values were determined from fits to the eqn (1).

Apparent kcat.

ND = not determined.

Specific activity, determined in triplicate with saturating concentrations of all substrates and activators.

Effects of Mg2+ on pyruvate carboxylation and MgADP phosphorylation

To determine the mechanistic role of free Mg2+ in the wild-type catalyzed carboxylation of pyruvate, Mg2+ was treated as a pseudo-reactant (17) and initial velocity patterns for Mg2+ vs. MgATP, Mg2+ vs. pyruvate and Mg2+ vs. acetyl-CoA were determined. The intersecting initial velocity pattern observed in the Mg2+ vs. MgATP plots (Figure S2) indicates that Mg2+ and MgATP add to the BC domain in rapid equilibrium with Mg2+ binding first. The dissociation constant for Mg2+ (Kia), determined from global fits of the data to eqn (2), was 1.2 ± 0.2 mM while the Kb for MgATP was 0.145 ± 0.009 mM. Increasing amounts of free Mg2+ also activated the phosphorylation of MgADP by carbamoyl phosphate, resulting in a linear increase in kcat (Figure S3). While high concentrations of free Mg2+ (>7mM) inhibited pyruvate carboxylation and the MgATP-cleavage, there was no inhibition of the MgADP phosphorylation reaction by Mg2+ (up to 11 mM).

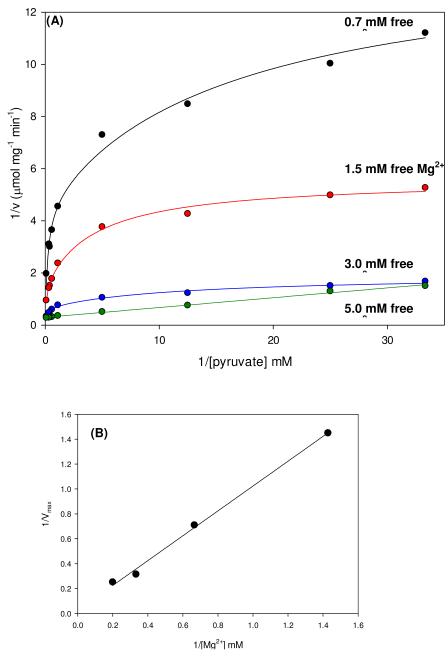

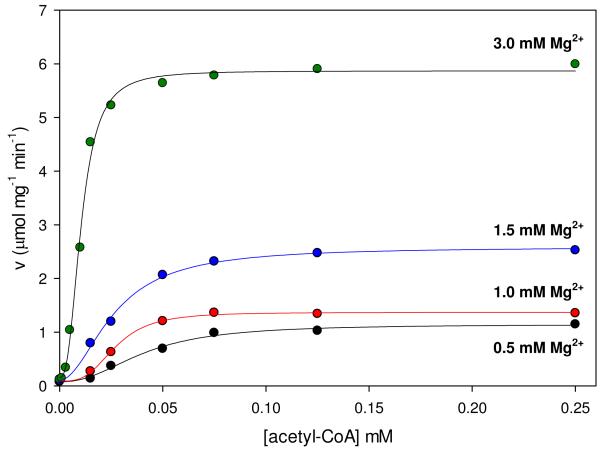

The initial velocities of the wild-type catalyzed carboxylation of pyruvate were also measured at several fixed concentrations of free Mg2+ and varying concentrations of pyruvate (Figure 1A). Nonlinear, concave downward reciprocal plots were observed at Mg2+ concentrations of 0.7-3.0 mM. Kinetic parameters determined from individual fits of these data to eqn (3) show that Mg2+ had a significant effect on the rate of pyruvate carboxylation but only a marginal effect on the Km for pyruvate (Table 2). At 5 mM free Mg2+, the reciprocal plot was linear and the data were fitted to eqn (1). A replot of the apparent 1/Vmax vs. 1/[Mg2+] (Figure 1B) was used to estimate the K for Mg2+ a for the effect on Vmax (≈ 40 mM). Similarly, the effects of free Mg2+ on the activation of the pyruvate carboxylation reaction by acetyl-CoA was determined by measuring the initial rates of oxaloacetate formation at varying concentrations of acetyl-CoA and fixed concentrations of Mg2+ (Figure 2). Kinetic parameters determined from individual fits of the data to eqn (4) show that increasing concentrations of Mg2+ had little effect on the sigmoidicity of the curves, indicated by the relatively minor variations in the determined Hill coefficients (Table 3). A steady increase in the rate of pyruvate carboxylation was observed with increasing concentrations of Mg2+, demonstrated most clearly in the observed 4.9-fold increase in kcat when concentrations of Mg2+ were increased from 0.5 to 3 mM. Small but significant decreases in the K for acetyl-CoA were observed at increasing Mg2+ a concentrations up to 1.5 mM (Ka = 38-25 μM). An overall 3.8-fold decrease in the Ka for acetyl-CoA (10 μM) was determined with the addition of 3.0 mM free Mg2+.

Figure 1.

(A) Nonlinear double reciprocal plots obtained when the initial rates of pyruvate carboxylation were determined at varying concentrations of pyruvate (0.03-10 mM) and fixed concentrations of free Mg2+ (0.7 mM, black; 1.5 mM, red; 3.0 mM, blue; 5.0 mM, green). Solid lines are the calculated individual fits of the data to eqn (3) for Mg2+ concentrations up to 3.0 mM and to eqn (1) for 5.0 mM Mg2+. (B) Replot of Vmax vs. 1/[Mg2+].

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters determined from measuring the initial rates of pyruvate carboxylation with varying concentrations of pyruvate at fixed concentrations of free Mg2+a.

| Vmax (μmol mg−1 min−1) |

Km pyruvate (mM) |

V/Km pyruvate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.7 mM Mg2+ | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 0.22 ± 0.03 |

| 1.5 mM Mg2+ | 1.41 ± 0.01 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 0.47 ± 0.08 |

| 3.0 mM Mg2+ | 3.18 ± 0.08 | 2.65 ± 0.04 | 1.2 ± 0.7 |

| 5.0 mM Mg2+ | 3.98 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 27.3 ± 0.5 |

Figure 2.

Initial rates of pyruvate carboxylation at varied concentrations of acetyl-CoA (0-0.25 mM) and fixed concentrations of free Mg2+ (0.5 mM, black; 1.0 mM, red; 1.5 mM, blue; 3.0 mM, green). Solid lines indicate the least-square individual fits to the Hill equation (eqn (4)).

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters determined from measuring the initial rates of pyruvate carboxylation with varying concentrations of acetyl-CoA at fixed concentrations of free Mg2+a.

| Vmax (μmol mg−1 min−1) |

Ka acetyl-CoA (μM) |

nacetyl-CoA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 mM Mg2+ | 1.16 ± 0.07 | 38 ± 2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| 1.0 mM Mg2+ | 1.39 ± 0.06 | 26 ± 2 | 2.8 ± 0.5 |

| 1.5 mM Mg2+ | 2.59 ± 0.08 | 25 ± 1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| 3.0 mM Mg2+ | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 10.0 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

Kinetic parameters were determined from data fits to eqn (4).

The dependence of pyruvate carboxylation, oxaloacetate decarboxylation and MgADP phosphorylation on pH

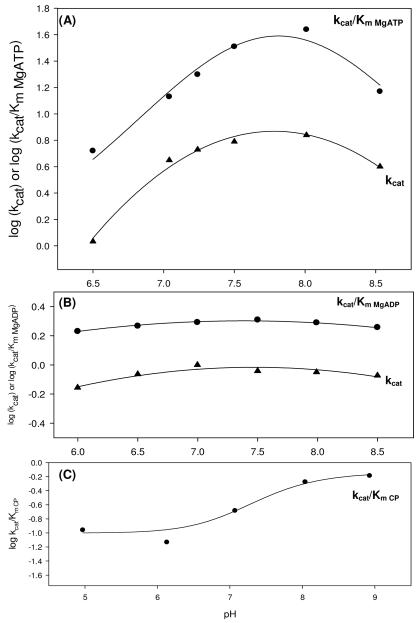

The dependence of kcat and kcat/Km on pH in the full forward and reverse reactions was examined for the wild-type RePC catalyzed reactions (Figure 3). When MgATP was the variable substrate, the kcat/Km pH profile for pyruvate carboxylation decreased at both high and low pH with pKas at approximately 8.0. The kcat pH profile for pyruvate carboxylation showed three pKas at 6.6, 7.4 and 8.5. In the reverse reaction, MgADP was varied while phosphate and oxaloacetate were held at fixed saturating concentrations. While the kcat/Km and kcat profiles appear deceptively flat, both sets of data were satisfactorily fitted to eqn (7) (σ=0.04), revealing two pKas near 5.2 and 9.4. Due to the instability of RePC at a pH less than 6 or greater than 8.5, the profile could not be extended further. The phosphorylation of MgADP, with carbamoyl phosphate as the varied substrate, exhibited only a partial dependence on pH and fits of the kcat/Km data to eqn (8) revealed pKas of 7.7 and 6.9 (Figure 3C). The kcat for the phosphorylation MgADP by carbamoyl phosphate was pH independent (data not shown).

Figure 3.

pH profiles for the pyruvate carboxylation reaction (A), full reverse reaction (B) and MgADP phosphorylation reaction (C) catalyzed by wild-type RePC. (A) For the dependence of kcat/Km for pyruvate carboxylation on pH, pK1 = 8.0 ± 0.1, pK2 = 8.09 ± 0.01 and pK0-pK2 = 8.2 ± 0.5 values were obtained with MgATP as the variable substrate and data fits to eqn (5). kcat data were fitted to eqn (6) and values of pK1 = 6.6 ± 0.8, pK2 = 8.5 ± 0.2 and pK0-pK2 = 7.4 ± 0.2 were obtained. (B) Two pKas were observed in both the kcat/Km MgADP (pK1 = 5.2 ± 0.1 and pK2 = 9.5 ± 0.2) and kcat (pK1 = 5.30 ± 0.08 and pK2 = 9.4 ± 0.1) pH profiles for the full reverse reaction (eqn (7)). (C) The pH had only a partial effect on phosphorylation of MgADP by carbamoyl phosphate and the kcat/Km pH profile showed two pKas (pK1= 6.9 ± 0.2 and pK2 = 7.7 ± 0.2) with carbamoyl phosphate was the variable substrate. Data were fitted to eqn (8).

Effects of acetyl-CoA on wild-type RePC activities and the coupling of the BC and CT domain reactions

Specific activities for each of the RePC catalyzed reactions were determined in the presence and absence of saturating concentrations of acetyl-CoA (Table 4). Acetyl-CoA had the greatest effect on the rate of pyruvate carboxylation, and its absence resulted in catalytic activities that were only 9% of the fully activated enzyme. The lack of acetyl-CoA also caused fairly drastic decreases in the rates of both MgATP hydrolysis and the full reverse reaction (82% and 78%, respectively). Acetyl-CoA also had a noticeable effect on the activity of the oxamate-induced decarboxylation of oxaloacetate but no effect on the rate of MgADP phosphorylation by carbamoyl phosphate.

Table 4.

Effect of acetyl-CoA on the activities of wild-type catalyzed reactionsa.

| (+) acetyl-CoA | (−) acetyl-CoA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| kcat(min−1)b | kcat(min−1) | % ratec | |

| Pyruvate carboxylation | 700 ± 20 | 65.8 ± 0.4 | 9 |

| Full reverse reaction | 0.835 ± 0.005 | 0.152 ± 0.03 | 18 |

| HCO3−-dependent ATPase | 2.58 ± 0.09 | 0.547 ± 0.002 | 22 |

|

Oxamate-induced

decarboxylation of oxaloacetate |

9.03 ± 0.04 | 6.00 ± 0.05 | 67 |

| ADP phosphorylation | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.43 ± 0.01 | 100 |

For detailed reaction conditions see methods section.

Specific activities were determined for each reaction, with saturating concentrations of all substrates, in triplicate. Errors reported are the standard deviations from those determinations.

Compared to the specific activity in the presence of acetyl-CoA.

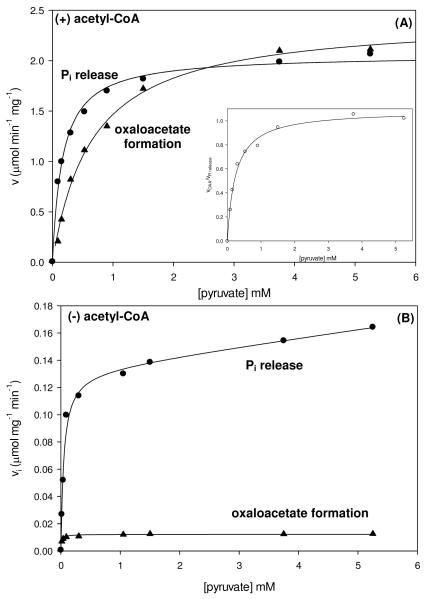

To assess the extent of coupling between MgATP-cleavage in the BC domain and carboxyl transfer in the CT domain, the rates of Pi release and oxaloacetate formation were measured under identical reaction conditions with varying amounts of pyruvate in the presence and absence of acetyl-CoA (Figure 4). The rates of both reactions exhibited a hyperbolic dependence on the concentration of pyruvate in the presence of saturating acetyl-CoA (Figure 4A) and kinetic parameters were determined from fits of the data to eqn (1) (Table 5). The Ka of pyruvate for the stimulation of Pi release was determined to be 0.16 ± 0.01 mM while the Km of pyruvate determined for the oxaloacetate formation was 4-fold greater. The decreased Ka for pyruvate for the stimulation of Pi release partially accounts for the 3.7-fold increase in the kcat/Ka compared to that determined when measuring the rate of oxaloacetate formation. A plot of the ratio of the rates of oxaloacetate formation to the rates of Pi release vs. pyruvate concentrations (Figure 4A inset) revealed a Ka for pyruvate of 0.25 mM and a limiting value of the ratio to be 1.08, indicating the complete coupling between the HCO3−-dependent MgATP-cleavage in the BC domain and oxaloacetate formation in the CT domain at saturating concentrations of pyruvate. While the ratio of the initial rates of oxaloacetate formation and Pi release did not reach 1:1 until concentrations of pyruvate ≈ 1 mM, a 300-500 fold stimulation of the rate of Pi release from the BC domain was observed at the lowest concentrations of pyruvate in the presence of acetyl-CoA.

Figure 4.

Initial rates of Pi release (●) and oxaloacetate formation (▲) at varying concentrations of pyruvate (0.03-5.25 mM) were determined to evaluate the extent of coupling between the HCO3−-ATP cleavage and pyruvate carboxylation reactions in the presence (A) and absence (B) of saturating concentrations of acetyl-CoA. Solid lines indicate the least-square fits to eqn (1). Inset: Ratio of the rates of oxaloacetate formation and Pi release (○) as a function of pyruvate concentrations. Solid lines indicate the least-square fits to eqn (1).

Table 5.

Effect of acetyl-CoA on the coupling of the HCO3−-dependent ATPase reaction in the BC domain to pyruvate carboxylation in the CT domaina.

| (+) acetyl-CoA | (−) acetyl-CoA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pi releasec |

% of (+) acetyl-CoAb |

||

| kcat (min−1) | 290 ± 5 | 16.9 ± 0.8 | 5.8 |

| Ka pyruvate (mM) | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.048 ± 0.008 | 30 |

| kcat/Ka (min−1 mM−1) | 1820 ± 10 | 350 ± 15 | 19 |

| Oxaloacetate formation | |||

| kcat (min−1) | 310 ± 8 | 1.52 ± 0.03 | 0.5 |

| Km pyruvate (mM) | 0.65 ± 0.05 | 0.013 ± 0.002 | 2 |

| kcat/Km (min−1 mM−1) | 470 ± 15 | 115 ± 5 | 24 |

Initial rates of Pi release and oxaloacetate formation were determined as detailed in the methods section both in the presence and absence of 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA at varying concentrations of pyruvate (0.03-5.25 mM) and 15 mM HCO3−.

Percentage of parameters determined without acetyl-CoA compared to those determined with acetyl-CoA.

Kinetic parameters were determined from fits of the data to eqn (1).

In the absence of acetyl-CoA (Figure 4B), the initial rates of oxaloacetate formation were fitted to eqn (1), giving a Km for pyruvate of 0.013 ± 0.002 mM, which was 50-fold lower than that determined in the presence of acetyl-CoA and 3.7-fold lower than the Ka of pyruvate determined for the stimulation of Pi release in the absence of acetyl-CoA (Table 5). The Ka for the pyruvate stimulation of the rates of Pi release in the absence of acetyl-CoA displayed a 3-fold decrease compared to the Ka determined with saturating acetyl-CoA. The 11-fold increase in the kcat for Pi release compared to oxaloacetate formation indicates a nearly complete lack of coupling between MgATP-hydrolysis and pyruvate carboxylation at saturating concentrations of pyruvate. In the absence of acetyl-CoA, the presence of low concentrations of pyruvate still resulted in a significant stimulation (120-175-fold increase) of the rates of Pi release from the BC domain.

Effects of free biotin on the BC domain reactions

The activation of the catalytic reactions occurring in the BC domain by free biotin were examined with a tetrameric enzyme that lacks tethered biotin (K1119Q mutant, 9, 18), a tetrameric holoenzyme where positioning of the tethered biotin favors placement in the BC domain (T882A mutant, 9), and with the tetrameric wild-type holoenzyme. The effect of 10 mM free biotin on the kinetic parameters for the wild-type, T882A and K1119Q RePC-catalyzed HCO3−-dependent ATPase reaction is shown in Table 6. Free biotin increases the kcat for both the wild-type and the T882A RePC-catalyzed reactions without having a major effect on the Km for MgATP. In the K1119Q catalyzed reaction, the addition of 10 mM biotin increases the kcat of MgATP-hydrolysis to rates observed for wild-type RePC in the absence of free biotin. This rate increase, coupled with a 35-fold decrease in the Km for MgATP, results in a nearly 1000-fold increase in the catalytic efficiency of the K1119Q RePC catalyzed reaction when 10 mM free biotin is added.

Table 6.

Effect of free biotin on the kinetic parameters for the HCO3−-dependent ATPase reaction catalyzed by the wild-type and mutant forms of RePC e.

| (+) 10 mM free biotin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (min−1)b |

Km MgATP (mM) |

kcat/Km (min−1 mM−1) |

% wild-type kcat/Km |

kcat (min−1) |

Km (mM) |

kcat/Km (min−1 mM−1) |

% wild-type kcat/Km |

|

| wild-type | 2.58 ± 0.09 | 0.022 ± 0.003 | 115 ± 2 | (100) | 3.02 ± 0.01 | 0.018 ± 0.007 | 167 ± 5 | (100) |

| K1119Q | 0.082 ± 0.001 | 1.20 ± 0.7 | 0.068 ± 0.005 | 0.06 | 2.69 ± 0.06 | 0.040 ± 0.001 | 67.5 ± 0.3 | 40 |

| T882A | 14 ± 2 | 0.054 ± 0.002 | 260 ± 15 | 225 | 38 ± 7 | 0.09 ± 0.05 | 430 ± 10 | 260 |

Reaction conditions: 50 mM Bis-Tris, 25 mM Tricine, 25 mM glycine (pH 7.5), 25° C, 15 mM HCO3−, 10 mM biotin, 7.5 mM MgCl2, MgATP (0.09-3.0 mM), 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA.

Data fitted to eqn (1).

The effect of free biotin on the RePC-catalyzed phosphorylation of MgADP using either carbamoyl phosphate or acetyl phosphate as a phosphoryl donor (Table 7) was also examined. While the overall rate of the wild-type catalyzed phosphorylation of MgADP was 4-times slower with acetyl phosphate as the phosphoryl donor, a significant decrease in the Km for acetyl phosphate, compared to carbamoyl phosphate, resulted in a kcat/Km value nearly twice that for carbamoyl phosphate in the absence of free biotin. The addition of 10 mM biotin to the wild-type catalyzed reactions increased the kcat of the phosphorylation of MgADP by carbamoyl phosphate but inhibited the rate of phosphorylation by acetyl phosphate. The T882A-catalyzed rate of MgADP phosphorylation with carbamoyl phosphate in the absence and presence of 10 mM biotin was 10- and 7.8- times greater, respectively, than the rate of the wild-type catalyzed reactions. In contrast, the rate of the T882A-catalyzed phosphorylation with acetyl phosphate was significantly lower than the wild-type rate of MgADP phosphorylation with acetyl phosphate. The addition of 10 mM free biotin reduced the rate of the T882A catalyzed phosphorylation with acetyl phosphate even further.

Table 7.

Activities of the wild-type and mutant RePC for the MgADP phosphorylation reaction using either carbamoyl phosphate or acetyl phosphate in the presence and absence of biotina.

| (+) 10 mM free biotin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (min−1)b |

Km (mM) |

kcat/Km (min−1mM−1) |

% wild- type kcat/Km |

kcat (min−1) |

Km (mM) |

kcat/Km (min−1 mM−1) |

% wild- type kcat/Km |

|

| Carbamoyl phosphate c | ||||||||

| wild-type | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | (100) | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | (100) |

| K1119Q | 0.014 ± 0.001 | 0.88 ± 0.07 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 17 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 45 |

| T882A | 24 ± 1 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 7.0 ± 0.6 | 750 | 32.1 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 11 ± 1 | 920 |

| Acetyl phosphate d | ||||||||

| wild-type | 0.58 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 1.70 ± 0.05 | (100) | 0.29 ± 0.002 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | (100) |

| K1119Q | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 1.62 ± 0.05 | 95 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 1.19 ± 0.02 | 57 |

| T882A | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 1.36 ± 0.01 | 80 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 40 |

Reaction conditions: 50 mM Bis-Tris, 25 mM Tricine, 25 mM glycine (pH 7.5), 25° C, 7.5 mM MgCl , 3.5 mM MgADP, 0.25 mM acetyl-CoA.

Data fitted to eqn (1).

Carbamoyl phosphate varied phosphoryl donor (1-20 mM).

Acetyl phosphate varied phosphoryl donor (0.1-20 mM).

Comparable to the effects observed for wild-type RePC, the T882A RePC mutant also exhibited a significantly reduced Km for acetyl phosphate when compared to carbamoyl phosphate, both in the presence and absence of 10 mM biotin. The K1119Q RePC mutant catalyzed the phosphorylation of MgADP using acetyl phosphate as the phosphoryl donor at rates comparable to wild-type RePC in the absence of free biotin. Despite effectively increasing the rates of MgADP phosphorylation with carbamoyl phosphate as the substrate, free biotin had only small effects on the kcat and kcat/Km when acetyl phosphate was the phosphoryl donor in the K1119Q-mutant catalyzed reaction.

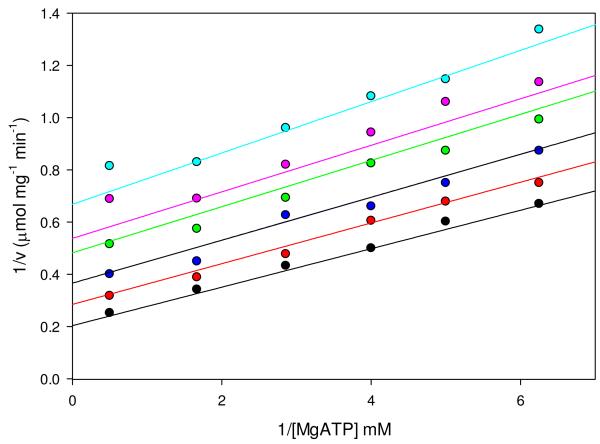

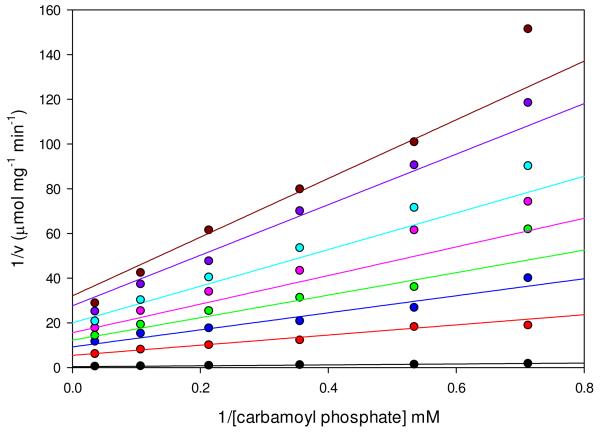

Inhibition of pyruvate carboxylation and MgADP phosphorylation by phosphonoacetate

Phosphonoacetate, an isosteric and isoelectronic analog of the putative carboxyphosphate intermediate, is an effective inhibitor of pyruvate carboxylation (Figure 5) and MgADP phosphorylation with carbamoyl phosphate (Figure 6) in the wild-type RePC reactions. Inhibition of pyruvate carboxylation with respect to MgATP by phosphonoacetate was noncompetitive and kinetic parameters determined from global fits of the data to eqn (9) are shown in Table 8. Kinetic parameters for the partial inhibition of MgADP phosphorylation by phosphonoacetate (Figure 6) were best defined from global fits of the data to eqn (10) describing hyperbolic, noncompetitive inhibition (Table 8). While only a partial inhibitor of the phosphorylation reaction, saturating concentrations of phosphonoacetate (Kid = 1.9 ± 0.3 mM) would result in nearly complete inhibition, with Vmax and V/Km values only 1% and 1.5% of the uninhibited catalytic reaction. The virtually identical slope and intercept inhibition constants (Kis = 0.027 ± 0.003 mM and Kii = 0.021 ± 0.001 mM) determined for the inhibition of MgADP phosphorylation by phosphonoacetate were 100-fold and 890-fold lower than similar inhibition constants determined for the phosphonoacetate inhibition of the pyruvate carboxylation reaction (Kis = 2.6 ± 0.3 mM and Kii = 18 ± 7 mM).

Figure 5.

Linear, noncompetitive inhibition of pyruvate carboxylation by phosphonoacetate with respect to MgATP. Initial rates were determined at varying concentrations of MgATP (0.16-2.0 mM) and fixed concentrations of phosphonoacetate (0 mM, black; 1.05 mM, red; 2.10 mM, blue; 3.6 mM, green; 4.2 mM, pink; 6.0 mM, cyan). Data were fitted to eqn (9) and the solid lines indicate the least-square fits to the equation. Kinetic parameters from these fits are shown in Table 8.

Figure 6.

Hyperbolic, noncompetitive inhibition of the ADP phosphorylation reaction by phosphonoacetate with respect to carbamoyl phosphate. Initial rates were determined at varying concentrations of carbamoyl phosphate (1.4-20 mM) and fixed concentrations of phosphonoacetate (0 mM, black; 0.33 mM, red; 0.66 mM, blue; 1.0 mM, green; 1.5 mM, pink; 2.5 mM, cyan; 7.0 mM, purple; 20 mM, dark red). Data were fitted to eqn (10) and the solid lines indicate the least-square fits to the equation. Kinetic parameters from these fits are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Inhibition of pyruvate carboxylation and MgADP phosphorylation by phosphonoacetate with respect to MgATP or carbamoyl phosphate

Discussion

Comparison of the kinetic parameters for PC from R. etli with PC from other sources

The rate of the wild-type RePC catalyzed oxaloacetate decarboxylation and subsequent formation of MgATP was only 0.2% of the rate of pyruvate carboxylation. Compared to the relative rates of the full forward and reverse reactions catalyzed by PC isolated from sheep (19) and chicken liver (20, 21), the rate of decarboxylation is significantly lower in RePC compared to the rate of carboxylation. This suggests that RePC may be designed to minimize the reversibility of the catalytic carboxylation of pyruvate. Detailed further in the two accompanying manuscripts (7, 13), the formation of a distinct salt bridge between Arg353 and Glu248 near the opening of the BC domain may preclude the access of carboxybiotin to the active site, effectively reducing the relative rate of carboxybiotin decarboxylation in the reverse reaction. Further, the rate of the RePC-catalyzed oxamate-stimulated decarboxylation of oxaloacetate was 2.0% of the full forward reaction, suggesting that an additional partially rate-limiting step may exist in the BC domain which influences the rate of the full reverse reaction.

To the best of our knowledge, acetyl phosphate has not been previously shown to be a suitable phosphoryl donor for the PC catalyzed phosphorylation of MgADP. While the kcat/Km for the wild-type catalyzed reaction with acetyl phosphate was almost twice that determined with carbamoyl phosphate as the substrate, the decreased kcat and Km for acetyl phosphate implies that the release of products is more rate-limiting compared to when carbamoyl phosphate is the substrate. The T882A RePC mutant also catalyzes the MgADP phosphorylation reaction with acetyl phosphate as a phosphoryl donor. The activating effect the T882A mutation has on the phosphorylation reaction with carbamoyl phosphate as the substrate, most likely due to the increased presence of the tethered biotin in the BC domain (9), is not observed when acetyl phosphate is used as the phosphoryl donor. In fact, the rate of the T882A RePC catalyzed phosphorylation of MgADP with acetyl phosphate was actually 52% less than that determined for the wild-type catalyzed reaction. This observation, coupled with the slight inhibitory effect of free biotin on the kcat for MgADP phosphorylation in the T882A RePC mutant, could indicate that binding of acetyl phosphate in the BC domain disfavors the binding of tethered or free biotin in the active site. Computational docking studies (13) show that acetyl phosphate adopts a conformation similar to carbamoyl phosphate in the active site which places the hydrophobic acetyl group near the biotin binding pocket.

The T882A RePC crystal structure co-crystallized with phosphonoacetate (13) also shows that phosphonoacetate can adopt multiple, energetically favorable conformations in the BC domain, specifically one where the phosphoryl group is positioned towards ADP and the other with the carboxyl-moiety is positioned towards ADP and near the Mg2+ center in the active site. This isosteric and isoelectronic inhibitory analog of the carboxyphosphate intermediate (22) is a noncompetitive inhibitor of pyruvate carboxylation and a partial noncompetitive inhibitor of the phosphorylation of MgADP with carbamoyl phosphate. Previous studies with sheep kidney PC have also shown that phosphonoacetate is a noncompetitive inhibitor with respect to MgATP for the full forward reaction with a Ki of 0.5 mM (22). The nearly identical values of Kii and Kis for phosphonoacetate determined for the inhibition of the phosphorylation reaction signifies the ability of phosphonoacetate to inhibit the activity equally as well in the presence or absence of carbamoyl phosphate. Presumably, the second Mg2+ in the BC domain active site will have available coordination sites that can be occupied by the carboxylic-end of phosphonoacetate prior to the formation of MgATP in the reaction, resulting in the significant inhibition by phosphonoacetate in the absence of carbamoyl phosphate in the active site. In the presence of carbamoyl phosphate, phosphonoacetate still remains a potent inhibitor of the phosphorylation reaction. This, coupled with the noncompetitive nature of the inhibition of the full forward reaction with respect to MgATP in both RePC and in sheep kidney PC (22), could indicate that phosphonoacetate may also bind in the position in the active site normally occupied by the γ-phosphoryl group of MgATP.

pH variation of the BC domain reactions of PC reveals the possible protonation state of the active site base

Previous studies have shown that the oxamate-induced decarboxylation of oxaloacetate in the CT domain is pH independent in avian PC (21). The proposed mechanism for pyruvate carboxylation in the CT domain of RePC, facilitated by a strictly conserved Thr residue (9), also suggests similar pH independence would be observed with the RePC enzyme. Therefore, the pH profiles for the overall forward and reverse reactions (Figure 3) are likely to reflect the pH dependence of reactions in the BC domain. In the forward reaction, the HCO3−-dependent cleavage of MgATP and subsequent carboxylation of the tethered biotin would result in the formation of MgADP, HPO42− and the enzyme-biotin-CO2− complex as products and the generation of a single proton due to the initial deprotonation of HCO3−. In the profiles where the concentrations of the nucleotides (either MgATP or MgADP) were varied, the pKs reflect those present in the enzyme-Mg2+ complex while the profile for the MgADP phosphorylation reaction, where the concentration of carbamoyl phosphate was varied, reveal the pKas present in the enzyme-Mg2+-MgADP complex.

While only speculative, the assignment of one of the pKas in the pH profiles to Glu305 agrees with the proposed catalytic function of this residue. Contained within the hydrogen-bonded catalytic triad composed of strictly conserved residues (Lys245-Glu305-Glu218), Glu305 is proposed to act as the active site base responsible for the deprotonation of HCO3− (Scheme 2). If this is the role of Glu305 in the catalytic mechanism, then it must remain ionized prior to the deprotonation of HCO3− in the forward reaction. The low side pKs observed in all the pH profiles indicate that the protonation of some residue in the active site appears to prevent catalysis in the forward and reverse reactions and reduces the catalytic activity in the otherwise pH independent MgADP phosphorylation reaction. The basic pK observed in both the full forward and reverse reactions suggests that making the active site more negative, through the loss of a proton, results in reduced catalysis for both these reactions.

Interestingly, the partial pH dependence for the phosphorylation reaction, where the dianionic carbamoyl phosphate is a substrate rather than the trianionic carboxyphosphate intermediate in the full reverse reaction, indicates that the active site prefers another negative charge. The wave-shaped kcat/Km pH profile with carbamoyl phosphate as the variable substrate also indicates that increasing pH facilitates the binding of the non-natural substrate. This could be attributed to the ionization of Glu305 or some other ionized residue in the active site. Since proton transfer is not involved in the actual catalytic phosphorylation of MgADP, the partial dependence on pH also implies that Glu305 may be protonated in the reverse reaction. Again, while the pKs observed in the pH profiles cannot be unambiguously assigned to specific residues in the BC domain active site, they do appear to agree with the proposed function of Glu305 as the active site base. A comprehensive discussion of the role of the Lys245-Glu305-Glu218 catalytic triad in the wild-type catalyzed pyruvate carboxylation reaction and further implications these pH profiles have on the proposed mechanism is detailed in the accompanying manuscript (7).

Free Mg2+ lowers the Ka for acetyl-CoA and aids in coupling the reactions of the BC and CT domain

The RePC holoenzyme structure (8) revealed the positioning of two Mg2+ ions in the BC domain, one which is coordinated to the β - and γ -phosphoryl oxygen of ATP-γ-S and the other which is coordinated to the α- and γ-phosphoryl oxygen. Presumably, one of the Mg2+ ions enters the BC domain as the MgATP complex (24). The initial velocity studies show that MgATP and free Mg2+ add to the active site in rapid equilibrium with Mg2+ binding first. Based on these studies, it is difficult to distinguish between a mechanism where acetyl-CoA initially binds to the enzyme or binds randomly with respect to free Mg2+. Even so, the initial velocity studies indicate that Mg2+ binds to the BC domain active site prior to MgATP and HCO3−. Since the essential activator binds in the BC domain active site, it was somewhat surprising that increasing concentrations of free Mg2+ had marked effects on the initial velocity plots when either acetyl-CoA or pyruvate were the varied components. In both cases, increasing concentrations of free Mg2+ increased the kcat for oxaloacetate formation, possibly by aiding in the proper orientation of the γ-phosphate of ATP in the active site. More puzzling is the observed decrease in the Ka for acetyl-CoA (Figure 2). While it could be postulated that Mg2+ binding in the BC domain induces significant conformational changes in the allosteric domain which would facilitate the binding of acetyl-CoA and therefore lower the apparent Ka of activation (24), there is currently no direct structural or kinetic evidence that this occurs in RePC.

The nonlinear dependence of pyruvate on the rate of the oxaloacetate formation at low concentrations of free Mg2+ (Figure 1) is indicative of incomplete coupling between the BC and CT domain reactions (25). Similar concave downward reciprocal plots have been observed for rat (26) sheep (27) and avian PC (28) catalyzed reactions. An investigation of the effects of free Mg2+ on the formation and stability of the enzyme-carboxybiotin complex of avian liver PC (20) show that the essential activator significantly decreases the amount of the nonproductive decarboxylation of carboxybiotin in the BC domain and pre-steady state kinetics (24) confirm that one possible role of Mg2+ in the carboxylation reaction is to increase the amount of productive MgATP-cleavage.

The presence of pyruvate stimulates the release of Pi from the BC domain

The binding of pyruvate in the CT domain, both in the presence and absence of acetyl-CoA, had a significant stimulatory effect on the rate of Pi release from the BC domain. The nearly 300-fold increase in the rate of Pi release observed with sub-saturating concentrations of pyruvate could be attributed to either an actual enhancement of the catalytic activity in the BC domain or to promoting the translocation of the BCCP-carboxybiotin domain (Figure 4). The correlation between pyruvate binding and the translocation of the BCCP domain to the CT domain has been well established in kinetic studies with PC (20, 29). While the current study cannot definitively exclude the possibility that pyruvate binding in the CT domain has an effect on the rate of MgATP-hydrolysis and carboxybiotin formation, both structural and kinetic evidence support the idea that the movement of the BCCP-biotin/carboxybiotin domain from the BC domain to the CT domain promotes the release of Pi from the BC domain.

The relative positioning of the BCCP and BC domains, disclosed in the accompanying manuscript (13), illustrates how the translocation of the BCCP domain upon pyruvate binding would result in the increased rate of Pi release without necessarily increasing the rate of the catalytic reaction. When the BCCP domain is interacting with the BC domain, it is positioned such that the random opening of the B-subdomain is effectively restricted, resulting in the slow release of products. Movement of the BCCP domain to the CT domain upon the binding of pyruvate would result in a significant increase in the rate of Pi release since the B-subdomain lid movements are no longer restricted. Despite the fact that the current crystal structures of the RePC holoenzyme (8, 13) give little insight into how pyruvate binding in the CT domain of one polypeptide chain can influence the translocation of the BCCP domain of a neighboring polypeptide chain, the overwhelming kinetic evidence suggests that there is communication between these two active sites mediated through interactions between BC, CT and BCCP-biotin domains.

Acetyl-CoA couples MgATP-hydrolysis/carboxybiotin formation in the BC domain with pyruvate carboxylation in the CT domain

It is apparent from Table 4, which shows the effect of acetyl-CoA on the specific activities of the various reactions catalyzed by RePC, that reactions involving the formation of the carboxyphosphate intermediate, namely the pyruvate carboxylation, oxaloacetate decarboxylation (full reverse) and HCO3−-dependent MgATP-cleavage reactions, are most affected by acetyl-CoA. As with the yeast PC isoenzyme 1 (Pyc1), acetyl-CoA had no effect on the rate of MgADP phosphorylation by carbamoyl phosphate (30), a reaction which does not proceed through the formation of the carboxyphosphate intermediate. Pre-steady state kinetic studies with avian PC (31) confirm that acetyl-CoA affects the ability of the enzyme to form the carboxyphosphate intermediate.

There are several possible mechanisms by which acetyl-CoA could facilitate the formation of the carboxyphosphate intermediate, one being to decrease the apparent Km for HCO3−. For example, the apparent Km for HCO3− observed with PC from B. Thermodenitrificans (32) was 16 mM in the presence of acetyl-CoA and the absence of acetyl-CoA resulted in a 25-fold increase in the Km for HCO3− (400 mM). Similar effects were observed in RePC where the Km for HCO3− in RePC determined in the presence of acetyl-CoA was 10.8 ± 0.4 mM, comparable to those for other bacterial PCs (33). A 40-fold decrease in the kcat for oxaloacetate formation was observed when the concentrations of HCO3− were decreased from 25 mM (Table 1) to 15 mM (Table 5) in the absence of acetyl-CoA, suggesting that acetyl-CoA may dramatically decrease the apparent Km for HCO3−.

In the presence of acetyl-CoA, a 1:1 coupling between the determined rates of Pi release and oxaloacetate formation is observed at saturating concentrations of pyruvate (Figure 4A). The complete coupling of the reactions of the two domains is not observed until concentrations of pyruvate reach approximately 1 mM, which is well above the reported intracellular concentrations of pyruvate (0.05-0.15 mM, 34). While inefficient, the abortive non-productive cleavage of MgATP in the BC domain in the presence of low levels of pyruvate can be explained by previous kinetic isotope effect studies (35). Once pyruvate binds in the CT domain, stimulating the release of Pi from the BC domain, it is only 50% committed to catalysis and will diffuse out from the active site prior to the arrival of the BCCP-carboxybiotin domain (35, 36). The ability of pyruvate to easily move in and out of the CT domain active site is also reflected in the increased Km for pyruvate determined for the full forward reaction compared to the Ka for pyruvate determined for the stimulation of Pi release. A definitive metabolic rationale for the observed lack of stoichiometry between the RePC-catalyzed MgATP cleavage in the BC domain and pyruvate carboxylation in the CT domain has not been established, although it is suggestive of a regulatory mechanism where elevated levels of pyruvate cause a hyper-compensatory increase in PC efficiency (37). While energetically inefficient at low concentrations of pyruvate, the amount of coupling between cleavage of MgATP and carboxyl transfer still would allow for the production of adequate amounts of oxaloacetate required to maintain essential anaplerotic and gluconeogenic functions (11, 33, 37). Further, given that Rhizobium etli contains both phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase and an α4 PC, both of which catalyze the MgATP-dependent conversion of pyruvate to oxaloacetate (11, 33), the metabolic consequences of the ineffective use of MgATP at low concentrations of pyruvate by RePC is most likely moderated by complex regulatory and compensatory mechanisms.

The complex, substrate-induced regulation of PC activity and efficiency is intimately intertwined with the allosteric regulation of the enzyme activity by acetyl-CoA. Both the kcat of Pi release and oxaloacetate formation are greatly diminished in the absence of acetyl-CoA and the reactions of the BC and CT domains are almost completely uncoupled at saturating concentrations of pyruvate. There are several possible reasons for the incomplete coupling of the two domains. If acetyl-CoA has an effect on the positioning and orientation of the CT domain, then its absence may result in pyruvate being tightly bound in the active site or carboxybiotin access to the active site being impeded, resulting in the increased stimulation of Pi release without an accompanying increase in oxaloacetate formation. Acetyl-CoA may also influence the placement of the BCCP domain near the BC domain. If this is true, then in the absence of acetyl-CoA the tethered-biotin may either be improperly positioned or not inserted into the BC domain, resulting in MgATP-cleavage but no carboxybiotin formation. The structural description of the interactions between the BCCP and BC domains indicate that the BCCP domain plays an active role in closing the B-subdomain lid to create a tighter, more compressed active site (13). Improper positioning of the BCCP domain could result in the opening of the B-subdomain lid and the release of PO43− prior to the deprotonation and carboxylation of the tethered biotin. Not only could the absence of acetyl-CoA result in the premature release of PO43−, but a looser active site could also result in the protonation or improper positioning of PO43− in the active site.

Kinetic evidence shows that acetyl-CoA is more likely to have an effect on the orientation and positioning of substrates in the BC domain active site. While pre-steady-state kinetic studies with avian PC (24, 31) have shown that there is incomplete coupling between MgATP-cleavage and carboxybiotin formation in the absence of acetyl-CoA, the current steady-state study cannot differentiate between the rates of Pi release and carboxybiotin formation. In fact, due to the complicated allosteric activation by acetyl-CoA and effects of various substrates on both the conformation and movement of the various domains in RePC, it is conceivable that there are several factors contributing to the uncoupling of the reactions of the two domains in the absence of acetyl-CoA. It is interesting to note that while the stimulatory effect of pyruvate on the release of Pi is not absolutely dependent on acetyl-CoA, it is completely dependent on the presence of tethered-biotin (9) suggesting that the stimulation and, consequently, the communication between the CT and BC domain is mediated through the BCCP-biotin domain.

Conclusions

The current steady-state kinetic study has given valuable insight into the activation and regulation of the α4 PC from R. etli. One of the more interesting aspects of the regulation and coordination of the catalysis in the BC and CT domains is that both activators and substrates will have stimulatory effects on the various reactions in the different active sites. Although the current structural descriptions of the RePC (8, 13) and SaPC (14) holoenzymes do not allow for elaboration on the structural basis by which acetyl-CoA and Mg2+ couple the MgATP-cleavage/biotin carboxylation in the BC domain with carboxyl transfer in the CT domain, these steady-state kinetic studies do denote a future direction for both kinetic and structural studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grant GM070455 to WWC, MStM, JCW and PVA and an NIH award F32DK083898 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive And Kidney Diseases to TNZ.

Abbreviations: PC, pyruvate carboxylase; BC, biotin carboxylase; CT, carboxyl transferase; BCCP, biotin carboxyl carrier protein; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; RePC, Rhizobium etli PC; hPC, human PC; SaPC, Staphylococcus aureus PC; BirA, biotin protein ligase; IPTG, isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside; NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; acetyl-CoA, acetyl-coenzyme A; NADP+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; Pi, inorganic phosphate; PNP, purine nucleoside phosphorylase; MESG, 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methyl purine riboside.

All amino acid numbering used in this manuscript is based on the R. etli pyruvate carboxylase sequence.

Supporting Information Available. The initial rate vs. [HCO3−] plot (Figure S1), initial velocity plots of the rates of pyruvate carboxylation at varied MgATP at fixed Mg2+ curves (Figure S2), and the effect of free Mg2+ on the rate of MgADP phosphorylation with saturating concentrations of carbamoyl phosphate (Figure S3) are provided in the supporting information. This material is available free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).For general reviews of PC function, structure and mechanism please see Jitrapakdee S, Vidal-Puig A, Wallace JC. Anaplerotic roles of pyruvate carboxylase in mammalian tissues. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2006;63:843–854. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5410-y. Attwood PV, Wallace JC. Chemical and catalytic mechanism of carboxyl transfer reaction in biotin-dependent enzymes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002;35:113–120. doi: 10.1021/ar000049+. Jitrapakdee S, St. Maurice M, Rayment I, Cleland WW, Wallace JC, Attwood PV. Structure, mechanism and regulation of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochem. J. 2008;413:369–387. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080709.

- (2).(a) Garcia-Cazorla A, Rabier D, Touati G, Chadefaux-Vekemans B, Marsac C, de Lonlay P, Saudubray J-M. Pyruvate carboxylase deficiency: metabolic characteristics and new neurological aspects. Ann. of Neurology. 2006;59:121–127. doi: 10.1002/ana.20709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Marin-Valencia I, Roe CR, Pascual JM. Pyruvate carboxylase deficiency: Mechanisms, mimics and anaplerosis. Mol. Gene. and Metab. 2010;101:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Fan TWM, Lane AN, Higashi RM, Farag MA, Gao H, Bousamra M, Miller DM. Altered regulation of metabolic pathways in human lung cancer discerned by 13C stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (SIRM) Mol. Cancer. 2009;8:1–19. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Jitrapakdee S, Wutthisathapornchai A, Wallace JC, MacDonald MJ. Regulation of insulin secretion: role of mitochondrial signaling. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1019–1032. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1685-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jitrapakdee S, Wallace JC. Structure, function and regulation of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochem. J. 1999;340:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3400001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Schär J, Stoll R. Regina, Schauer K, Loeffler DIM, Eylert E, Joseph B, Eisenreich W, Fuchs TM, Goebel W. Pyruvate carboxylase plays a crucial role in carbon metabolism of extra- and intracellularly replicating Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacterio. 2010;192:1774–1778. doi: 10.1128/JB.01132-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Eisenreich W, Slaghuis J, Laupitz R, Bussemer J, Stritzker J, Schwarz C, Schwarz R, Dandekar T, Goebel W, Bacher A. 13C isotopologue perturbation studies of Listeria monocytogenes carbon metabolism and its modulation by the virulence regulator PrfA. PNAS. 2006;103:2040–2045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507580103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Benton BM, Zhang JP, Bond S, Pope C, Christian T, Lee L, Winterberg KM, Schmid MB, Buysse JM. Large-scale identification of genes required for full virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacterio. 2004;186:8478–8489. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8478-8489.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kohler C, Wolff S, Albrecht D, Fuchs S, Becher D, Büttner K, Engelmann S, Hecker M. Proteome analyses of Staphylococcus aureus in growing and non-growing cells: a physilogical approach. Int. J. of Med. Micro. 2005;295:547–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zeczycki TN, Menefee AL, Adina-Zada A, Jitrapakdee S, Wallace JC, Attwood PV, St. Maurice M, Cleland WW. Novel Insights into the Biotin Carboxylase Domain Reactions of Pyruvate Carboxylase from Rhizobium etli. Biochemistry. 2011 doi: 10.1021/bi2012788. (accompanying manuscript in this series) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).St. Maurice M, Reinhardt L, Surinya KH, Attwood PV, Wallace JC, Cleland WW, Rayment I. Domain architecture of pyruvate carboxylase, a biotin-dependent multifunctional enzyme. Science. 2007;317:1076–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.1144504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Zeczycki TN, St. Maurice M, Jitrapakdee S, Wallace JC, Attwood PV, Cleland WW. Insight into the carboxyl transferase domain mechanism of pyruvate carboxylase from Rhizobium etli. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4305–4313. doi: 10.1021/bi9003759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zeczycki TN, St. Maurice M, Attwood PV. Inhibitors of pyruvate carboxylase. Open Enzy. Inhib. J. 2010;3:8–26. doi: 10.2174/1874940201003010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) Encarnacion S, Dunn M, Willms K, Mora J. Fermentative and aerobic metabolism in Rhizobium etli. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:3058–3066. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3058-3066.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dunn MF, Araicza G, Cevallos MA, Mora J. Regulation of pyruvate carboxylase in Rhizobium etli. FEMS Micro. Lett. 2006;157:301–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Sauer U, Eikmanns BJ. The PEP-pyruvate-oxaloacetate node as the switch point for carbon flux distribution in bacteria. FEMS Micro. Rev. 2005;29:765–794. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lietzan AD, Menefee AL, Zeczycki TN, Kumar S, Attwood PV, Wallace JC, Cleland WW, St. Maurice M. Interaction between the biotin carboxyl carrier domain and the biotin carboxylase domain in the asymmetrical pyruvate carboxylase tetramer from Rhizobium etli. Biochemistry. 2011 doi: 10.1021/bi201277j. (accompanying manuscript in this series) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Xiang S, Tong L. Crystal structures of huamn and Staphylococcus aurues pyruvate carboxylase and molecular insights into the carboxyltransfer reaction. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biolo. 2008;15:295–302. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu LPC, Xiang S, Lasso G, Gil D, Valle M, Tong L. A Symmetrical Tetramer for S. aureus Pyruvate Carboxylase in Complex with Coenzyme A. Structure. 2009;17:823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lasso G, Yu LPC, Gil D, Xiang S, Tong L, Valle M. Cryo-EM Analysis reveals new insights into the mechanism of action of pyruvate carboxylase. Structure. 2010;18:1300–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ellis KJ, Morrison JF. Buffers of constant ionic strength for studying pH-dependent processes. Meth. Enzymol. 1982;87:405–426. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)87025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Cleland WW. Statistical analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Methods in Enzymology. 1979;63:103–138. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)63008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Cook PF. Kinetic studies to determine the mechanism of bovine liver glutamate dehydrogenase by nucleotide effectors. Biochemistry. 1982;21:113–116. doi: 10.1021/bi00530a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Viola RE, Cleland WW. Initial velocity analysis for terreactant mechanisms. Methods Enzymol. 1982;87:353–366. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)87021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Adina-Zada A, Jitrapakdee S, Surinya KH, Mcldowie MJ, Piggott MJ, Cleland WW, Wallace JC, Attwood PV. Insight into the mechanism and regulation of pyruvate carboxylase by characterization of a biotin-deficient mutant of the Bacillus thermodenitrificans enzyme. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008;40:1743–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Keech DB, Utter MF. Pyruvate carboxylase. II. Properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1963;238:2609–2614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ashman LK, Keech DB, Wallace JC, Nielsen J. Sheep kidney pyruvate carboxylase. Studies on its activation by acetyl coenzyme A and characterization of its acetyl coenzyme A independent reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;18:5818–5824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Attwood PV, Wallace JC, Keech DB. The carboxybiotin complex of pyruvate carboxylase. A kinetic analysis of the effects of Mg2+ ions on its stability and on its reaction with pyruvate. Biochem. J. 1984;219:243–251. doi: 10.1042/bj2190243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Attwood PV, Wallace JC. The carboxybiotin complex of chicken liver pyruvate carboxylase. A kinetic analysis of the effects of acetyl-CoA, Mg2+ ions and temperature on its stability and on its reaction with 2-oxobutyrate. Biochem. J. 1986;235:359–364. doi: 10.1042/bj2350359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Attwood PV, Cleland WW. Decarboxylation of oxaloacetate by pyruvate carboxylase. Biochemistry. 1986;25:8191–8196. doi: 10.1021/bi00373a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ashman LK, Keech DB. Sheep kidney pyruvate carboxylase. Studies on the coupling of adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis and CO2 fixation. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:14–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Chou C-Y, Yu LPC, Tong L. Crystal structure of biotin carboxylase in complex with substrates and implications for its catalytic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:11690–11697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805783200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Branson JP, Attwood PV. Effects of Mg2+ on the pre-steady-state kinetics of the biotin carboxylation reaction of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7480–7491. doi: 10.1021/bi992825v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Easterbrook-Smith SB, Wallace JC, Keech DB. A reappraisal of the reaction pathway of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochem. J. 1978;169:225–228. doi: 10.1042/bj1690225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).McClure WR, Lardy HA, Kneifel HP. Rate liver pyruvate carboxylase I. Preparation, properties and cation specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1971;246:3569–3578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Scrutton MC, Keech DB, Utter MF. Pyruvate carboxylase IV. Partial reactions and the locus of activation by acetyl coenzyme A. J. Biol. Chem. 1965;240:574–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Taylor H, Nielsen J, Keech DB. Substrate activation of pyruvate carboxylase by pyruvate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1969;37:723–728. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(69)90951-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Goodall GJ, Baldwin GS, Wallace JC, Keech DB. Factors that influence the translocation of the N-carboxybiotin moiety between the two sub-sites of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochem. J. 1981;199:603–609. doi: 10.1042/bj1990603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).(a) Branson JP, Nezic M, Wallace JC, Attwood PV. Kinetic characterization of yeast pyruvate carboxylase isozyme Pyc1. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4459–4466. doi: 10.1021/bi011888m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Branson JP, Nezic M, Jitrapakdee S, Wallace JC, Attwood PV. Kinetic characterization of yeast pyruvate carboxylase isozyme Pyc1 and the Pyc1 mutant, C249A. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1075–1081. doi: 10.1021/bi035575y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Legge GB, Branson JP, Attwood PV. Effects of acetyl CoA on the pre-steady-state kinetics of the biotin carboxylation reaction of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3849–3856. doi: 10.1021/bi952797q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Libor SM, Sundaram TK, Scrutton MC. Pyruvate carboxylase from a thermophilic Bacillus. Studies on the specificity of activation by acyl derivatives of coenzyme A and on the properties of catalysis in the absence of activator. Biochem. J. 1978;169:543–558. doi: 10.1042/bj1690543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]