Abstract

A severe variant of vasovagal syncope, observed during tilt tests and blood donation has recently been termed “prolonged post-faint hypotension” (PPFH). A 49-year-old male with a life-long history of severe fainting attacks underwent head-up tilt for 20 min, and developed syncope 2 min after nitroglycerine spray. He was unconscious for 40 s and asystolic for 22 s. For the first 2 min of recovery, BP and HR remained low (65/45 mmHg and 40 beats/min) despite passive leg-raising. Blood pressure (and symptoms) only improved following active bilateral leg flexion and extension (“dynamic tension”). During PPFH, when vagal activity is extreme, patients may require central stimulation as well as correction of venous return.

Introduction

In this edition of Clinical Autonomic Research we describe the hemodynamic data of seven patients with a prolonged recovery after a vasovagal faint [20]. All patients were bradycardic, very hypotensive and highly symptomatic, complaining of weakness, malaise and nausea. This severe variant of vasovagal syncope was already described in 1919 by Cotton and Lewis [3] and has been reported since by several authors [6–8, 10, 17, 19]. It is also known to occur in the setting of blood donation [4, 15]. We propose to coin the term “prolonged post-faint hypotension” (PPFH) for this condition [1]. We postulate that in PPFH, sustained high vagal outflow results in pronounced bradycardia and decreased cardiac contractility resulting in loss of cardiac output and systemic blood pressure [20].

In the seven patients we studied 30° head-down tilting, a manoeuver that increases venous return, did not significantly increase blood pressure [20]. In the present case history we demonstrate that dynamic leg flexion and extension (dynamic tension) can be applied as an intervention to reverse PPFH.

Case history

A 49-year-old male patient was referred to our syncope unit with a medical history suggestive of intermittent convulsive vasovagal syncope. The episodes were induced by pain and had persisted since childhood. He used no medications and had no history of cardiovascular or neurological disease.

A diagnostic tilt table test was performed using a Nexfin device [5]. Stroke volume was computed by pulse wave analysis [9].

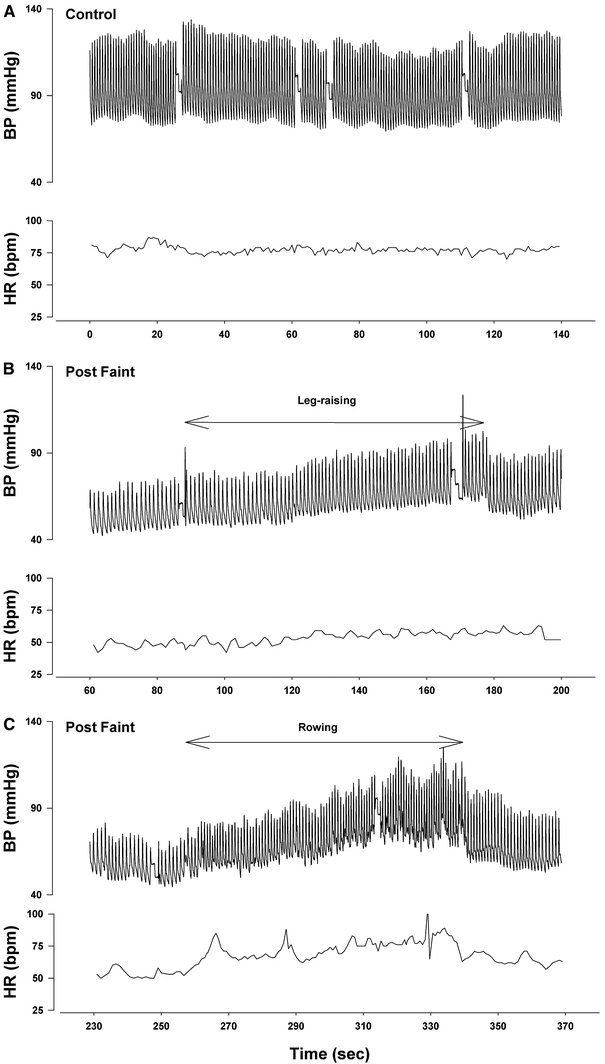

The upper arm blood pressure, measured via sphygmomanometer with the patient lying supine prior to tilt was 136/82 mm Hg and the heart rate 65 beats/min. Haemodynamic adjustments were normal during the first 20 min of unmedicated head-up tilt. About 2 min after nitroglycerine administration, severe vasovagal syncope occurred, associated with an asystolic period of 22 s. The patient was rapidly tilted back to the horizontal position. Myoclonic jerks and snoring were observed during the ensuing period of unconsciousness which lasted about 40 s. After this a stable blood pressure signal was obtained (Fig. 1). Initial BP was 65/45 mm Hg and HR 40 beats/min. The patient was severely symptomatic, complaining of general malaise, weakness and nausea. Leg-raising for 90 s achieved minimal increase in BP and HR and the symptoms remained; however, CO increased from 4.0 to 5.1 L/min during this time (Fig. 1). After lowering the legs BP returned to very low values. The patient then undertook bilateral leg flexion and extension exercises (dynamic tension) over a 70-s period. This manoeuver resulted in a rapid recovery of HR and CO. As HR increased, symptoms disappeared. In the last 10 s of this exercise HR increased to 80 beats/min, CO to 6.0 L/min and BP to 115/70 mm Hg. After stopping exercise, BP returned to low values and mild symptoms recurred (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of leg-raising and leg contraction and extension exercises on blood pressure. (a) Supine Control. (b) Effect of leg-raising post-faint. Note only minimal change in blood pressure and no change in heart rate. (c) Effect of leg contraction and extension (rowing). Note marked increases in heart rate and blood pressure

Comments

PPFH occurred in 7/391 (1.8%) consecutive patients referred to our syncope unit over a period of 20 months [20]. In a study of more than 6 million whole blood donations syncopal-type adverse reactions occurred in 2.7% [4]. Prolonged duration of syncope (and recovery) was present in only 1.5% of these syncopal-type adverse reactions. Another variant of delayed recovery from vasovagal syncope is the patient who initially regains his (or her) blood pressure in the horizontal position, but stands up too quickly and suffers a further attack. “Status vasovagalis” has been suggested to describe this derangement of the circulation [6, 7, 18]. Sir Thomas Lewis (1881–1945) reported that this phenomenon could last up to 1 h after the first attack [13]. Despite its low frequency, PPFH is a clinically relevant condition, since patients are highly symptomatic and recovery is severely protracted.

In hypovolemic states passive leg-raising is reported to be effective by increasing central blood volume and thereby cardiac output. This intervention is generally advised to reverse post-faint hypotension [14]. However, our observations in this study and the ineffectiveness of head-down tilting in the PPFH series [20] would suggest that manoeuvers that increase venous return [2, 10] do not help these patients. Thus, to overcome PPFH, something more than an increase in venous return is needed.

In our patient, we observed that active rapid flexion and extension of the legs, a manoeuver that increases venous return and stimulates the central pathways, resulted in rapid recovery of heart rate and blood pressure with disappearance of symptoms (Fig. 1). This is in excellent accordance with the findings of Engel and Romano that whole body exercise can overcome the vasovagal reaction [6, 7]. These investigators showed, like we did, that the effects of dynamic exercise are transient if the inhibiting stimulus is very strong [6, 7]. Like Cotton and Lewis [3] we observed that heart rate slowing and symptoms go hand in hand. In previous studies we used lower body tensing to abort impending faints and this intervention is now generally accepted to be effective [12]. Under the circumstances of PPFH, we prefer dynamic tension because during faint, muscle tone is impaired [6, 7, 13] and patients find sustained static exercise difficult to perform.

Based on our observation in this case history, the older literature [6, 7] and our recent findings in patients with vagovagal syncope [11] we postulate that diminished capacity to activate the central sympathetic pathways and thereby overcome exaggerated vagal activity is a key abnormality in patients with severe vasovagal faints. Furthermore, there is good evidence that exercise is a potent mechanism for inhibiting the vagus and increasing sympathoconstrictor activity via central command or muscle chemo and mechanoreflexes [16]. Other time-honoured remedies employed to ameliorate prolonged recovery after a faint include slapping the face, splashing it with cold water and administering smelling salts [6, 19]. Smelling salts (sal volatile), a combination of ammonium carbonate and perfume, were quite popular in the 19th century to revive fainting ladies of delicate sensibilities. A smelling salt container was held under the nose. Slightly noxious fumes coming from the container irritated the mucous membranes lining the nose, throat and lungs resulting in a stimulatory effect. Today, smelling salts are still used to revive boxers in the ring. These time-honoured remedies have a strong historical track record and may have a sound theoretical basis as a means of stimulating central excitatory sympathetic pathways and inhibiting vagal outflow. Additional measures mentioned to improve recovery after a vasovagal faint are drinking cold water or cold soup, or eating something. However, no actual physiologic measurements have been undertaken to support the effectiveness of these interventions.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Busweiler L, Jardine DL, Frampton CM, Wieling W. Sleep syncope: important clinical associations with phobia and vagotonia. Sleep Med. 2010;11:929–933. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavallaro F, Sandroni C, Marano C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of passive leg raising for prediction of fluid responsiveness in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1475–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1929-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotton TF, Lewis T (1918–1919) Observations upon fainting attacks due to inhibitory cardiac impulses. Heart 7:23

- 4.Eder AF, Dy BA, Kennedy JM, et al. The American Red Cross donor hemovigilance program: complications of blood donation reported in 2006. Transfusion. 2008;48:1809–1819. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eeftinck Schattenkerk DW, Van Lieshout JJ, Van den Meiracker AH, et al. Nexfin noninvasive continuous blood pressure validated against Riva-Rocci/Korotkoff. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:378–383. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel CL, Romano J, McLin T. Vaosdepessor and carotid sinus syncope: EEG, ECG and clinical observations. Arch Intern Med. 1944;74:100–119. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engel CL, Romano J. Studies of syncope; biologic interpretation of vasodepressor syncope. Psychosom Med. 1947;9:288–294. doi: 10.1097/00006842-194709000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gastaut H (1974) Syncopes: generalized anoxic cerebral seizures. In: Magnus O, Haas AM (eds). Handbook of clinical neurology, Chapter 42, Vol 15. North Holland, Amsterdam, 815–836

- 9.Harms MPM, Wesseling KH, Pott F, Jenstrup M, Van Goudoever J, Secher NH, Van Lieshout JJ. Continuous stroke volume monitoring by modelling flow from non-invasive measurement of arterial pressure in humans under orthostatic stress. Clin Sci. 1999;97:291–301. doi: 10.1042/CS19990061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harms MPM, Van Lieshout JJ, Jenstrup M, Pott F, Secher NH. Postural effects on cardiac output and mixed venous oxygen saturation in humans. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:611–616. doi: 10.1113/eph8802580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jardine DL, Krediet CT, Cortelli P, Frampton CM, Wieling W. Sympatho-vagal responses in patients with sleep and typical vasovagl syncope. Clin Sci. 2010;117:345–353. doi: 10.1042/CS20080497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krediet CTP, van Dijk N, Linzer M, van Lieshout JJ, Wieling W. Management of vasovagal syncope. Controlling or aborting faints by leg crossing and muscle tensing. Circulation. 2002;106:1684–1689. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000030939.12646.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis T. Vasovagal syncope and the carotid sinus mechanism. Br Med J. 1932;1:873–876. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.3723.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, Blanc JJ, Brignole M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2631–2671. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poles FC, Boycott M. Syncope in blood donors. Lancet. 1942;240:531–535. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)58098-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowell LB, O’Leary DS. Reflex control of the circulation during exercise: chemoreflexes and mechanoreflexes. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69:407–418. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton R. Vasovagal syncope: prevalence and presentation. An algorithm of management in the aviation environment. Eur Heart J Suppl. 1999;1:D109–D113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thijs RD, Wieling W, van Dijk JG. Status vasovagalis. Lancet. 2009;373:2222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss S, Baker J. The carotid sinus reflex in health and disease. Medicine. 1933;12:297–354. doi: 10.1097/00005792-193309000-00003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wieling W, Rozenberg J, Schon IK, Karemaker JM, Westerhof BE, Jardine DL (2011) Haemodynamic mechanisms underlying prolonged post-faint hypotension. Clin Auton Res. doi:10.1007/s10286-011-0134-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]