Abstract

Background

The present study examines the presentation and outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) at a Western centre over the last decade.

Methods

Between January 2000 and September 2009, 1010 patients with HCC were evaluated at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). Retrospectively, four treatment groups were classified: no treatment (NT), systemic therapy (ST), hepatic artery-based therapy (HAT) and surgical intervention (SI) including radiofrequency ablation, hepatic resection and transplantation. Kaplan–Meier analysis assessed survival between groups. Cox regression analysis identified factors predicting survival.

Results

Patients evaluated were 75% male, 87% Caucasian, 84% cirrhotic, and predominantly diagnosed with hepatitis C. In all, 169 patients (16.5%) received NT, 25 (2.4%) received ST, 529 (51.6%) received HAT and 302 (29.5%) received SI. Median survival was 3.6, 5.6, 8.8, and 83.5 months with NT, ST, HAT and SI, respectively (P = 0.001). Transplantation increased from 9.5% to 14.2% after the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) criteria granted HCC patients priority points. Survival was unaffected by bridging transplantation with HAT or SI (P = 0.111). On multivariate analysis, treatment modality was a robust predictor of survival after adjusting for age, gender, AFP, Child–Pugh classification and cirrhosis (P < 0.001, χ2 = 460).

Discussion

Most patients were not surgical candidates and received HAT alone. Surgical intervention, especially transplantation, yields the best survival.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, resection, chemotherapy, outcomes, transplant, palliation

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common solid malignancy worldwide, with more than 1 million new diagnoses made each year. Prognosis remains extremely poor with more than 600 000 deaths occurring annually, and a 5-year survival rate of less than 5% without treatment.1,2 In the United States, the current steady rise in incidence is largely as a result of hepatitis C (HCV).3 While recognized risk factors include viral hepatitis, hereditary haemochromatosis and environmental toxins, hepatitis B (HBV) and HCV are the predominant causes of HCC worldwide. Cirrhosis is present in 50–80% of patients who develop HCC.4–6

Surgical resection and liver transplantation are still the primary curative options for HCC. Liver transplantation offers a potential cure for the disease and also addresses underlying cirrhosis, which itself can behave as a premalignant condition.7–10 The role of liver transplantation has evolved over time. An important modification was the adaptation by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) of the United States to provide priority to HCC patients listed for liver transplantation who present with early-stage HCC under the Milan criteria.7,9–12

However, less than 20% of patients are deemed eligible for curative resection in the United States and few patients actually receive a liver transplantation as a result of limited organ availability.13–15 Over the past two decades, major advances in the understanding of HCC tumour biology have led to new therapeutic options, significantly altering clinical management. Beyond the minority of patients who are candidates for curative surgical intervention, a multimodal management approach for non-surgical candidates provides a greater focus on slowing or even reversing tumour progression. The primary goal is to extend survival for non-surgical candidates for possible curative surgery or liver transplantation. Directed hepatic arterial-based loco-regional therapy, including bland embolization, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) and yttium90 microsphere radioembolization (Y90), utilizes differential hepatic artery blood supply for tumour growth.16–21 Several studies have shown promising results with loco-regional transarterial-based treatment, including tumour necrosis and a delay in tumour progression and vascular invasion.16 Hepatic transarterial treatment is also utilized to downstage patients who exceed the Milan transplant criteria and to bridge patients awaiting transplantation.8,22–25 Local ablative treatment has also emerged as an important therapeutic option, especially in the cirrhotic liver. Ablative techniques cause cellular damage and achieve therapeutic effect by modifying temperature (radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation, or cryoablation) or by direct exposure to toxic substances (ethanol or acetic acid injection). Studies have demonstrated similar overall survival rates for ablative treatment and liver resection.26–33 Systemic treatment options for unresectable HCC are limited. Sorafenib, a multi-kinase inhibitor, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2007.34 The Sorafenib HCC Assessment Randomized Protocol (SHARP) trial shows it is the first systemic chemotherapeutic agent that has been shown to improve survival.34–36

While many large series report the management of HCC, most are from Asian countries where HCC is endemic.37–43 The purpose of the present study was to describe the presentation, management and outcome of patients with HCC who are managed at a single large Western tertiary care centre.

Methods

Between January 2000 and September 2009, 1010 patients diagnosed with HCC were evaluated at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Liver Cancer Center (LCC) in Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Data were analysed retrospectively from a prospective Institutional Review Board-approved hepatic cancer registry. Factors examined included demographics (age, gender and race), presence of cirrhosis, aetiology of hepatitis, Child–Pugh classification, clinical laboratory values, treatment modality and survival outcome.

Diagnosis of HCC was made during initial evaluation or before referral to the LCC. Evaluation included clinical laboratory values (complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, coagulation studies and liver function tests), hepatitis screening, analysis for tumour markers [alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), CEA and CA19-9] and radiographical studies including a triphasic helical computed axial tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A liver biopsy was performed when a diagnosis could not be determined based on laboratory (AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL) and radiographical data alone. Diagnosis and treatment recommendations were made for all patients at a weekly multidisciplinary liver tumour conference.44

Patients were categorized into four main treatment groups: no treatment (NT), systemic therapy (ST), hepatic artery-based therapy (HAT) and surgical intervention (SI). The NT group included patients who received best supportive care only. The ST group included patients who received oral systemic sorafenib treatment. The HAT group included patients who received bland embolization, TACE or Y90 treatment alone. The SI group included patients who underwent RFA, hepatic resection or liver transplantation. TACE, Y90 and RFA were performed as described previously.22,45,46

As a result of the complexity of analysing multimodal management, patients who ever received surgical therapy were classified in the SI group regardless of prior or subsequent HAT therapy. Within the SI group, patients were classified under the RFA treatment group regardless of prior HAT, hepatic resection group regardless of prior HAT or RFA, and liver transplantation group regardless of any type of prior therapy.

Comparisons were also made between two time periods: before the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) criteria change in March 2003 and after the MELD criteria change which granted priority points to patients with HCC. The two eras were defined as the pre-current MELD era (January 2000 until March 2003) and the current MELD era (March 2003 until September 2009).

Data analysis was performed using PASW Statistics 18 for Windows (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Groups were compared using the χ2 test for independence for categorical variables. Analysis of variance was used for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann–Whitney U- and Kruskal–Wallis tests were employed for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Overall survival was the primary endpoint of the study. Duration of survival was calculated from the time of evaluation at the LLC to death or loss to follow-up. Actuarial survival was calculated using Life Tables. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to compare survival between groups. Cox regression analysis was used to test predictors of survival. Variables that were found to significantly predict survival were included in a multivariate Cox regression model.

Results

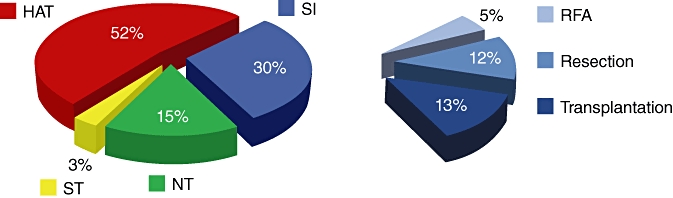

Between January 2000 and September 2009, 1010 patients diagnosed with HCC were managed at the UPMC LCC whose treatments are summarized in Fig. 1. In all, 639 (63.3%) patients had HAT with or without subsequent therapy, 448 (44.4%) received TACE and 174 (17.2%) received Y90 with or without subsequent therapy, 529 patients received HAT alone; 20 (2.0%), 371 (36.7%) and 138 (13.7%) patients received bland embolization, TACE and Y90 alone, respectively. Subgroup analysis of the SI group shows that 12 (22.6%) patients with RFA received additional HAT before or after ablation (eight patients received TACE and four received Y90). Analysis of patients with a liver resection showed 27 (22.0%) received additional HAT before or after surgery (17 patients received TACE and 10 received Y90). Patients with liver transplantation received the most additional therapy; only 31 (24.6%) received a transplant alone, 52 (41.3%) transplanted patients had prior TACE, 19 (15.1%) had prior Y90, 19 (15.1%) had prior RFA and 5 (4.0%) had a prior resection and 7 (5.6%) patients received both SI and HAT before transplantation. Overall, 121 (12.0%) patients had multimodal therapies, of which 75 were bridged transplants.

Figure 1.

Breakdown of treatment modalities for hepatocellular carcinoma patients. NT, no treatment; ST, systemic therapy; HAT, hepatic artery-based therapy; SI, surgical intervention; RFA, radiofrequency ablation

Patient demographics, presence of cirrhosis, etiology of hepatitis and Child–Pugh classification is presented for all patients and by treatment group in Table 1. Data were available for age, gender, cirrhosis, hepatitis, Child–Pugh classification, and ethnicity for 1010 (100%), 1007 (99.7%), 923 (91.4%), 901 (89.2%), 989 (97.9%), and 996 (98.6%) patients, respectively, and all percentages shown in Table 1 refer to available data only. Patients with ‘no viral hepatitis’ had a negative screen for HBV and HCV. It is unclear whether this is underestimated as a result of missing data for hepatitis screening in 109 (10.8%) patients. There are also more patients with Child–Pugh classifications than cirrhotic patients because of a lack of recorded cirrhosis data for 87 (8.6%) patients. Most patients were Caucasian males with underlying viral hepatitis and cirrhosis, and were not candidates for surgical treatment. HAT and SI tended to be offered to more Child–Pugh class A patients and those without underlying cirrhosis, whereas NT and ST was offered to more Child–Pugh class B and C patients with underlying cirrhosis.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of all patients and by treatment modality

| NT | ST | HAT | SI | P-value | Alla | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 154 (15.2%) | 25 (2.5%) | 529 (52.4%) | 302 (29.9%) | 1010 | |

| Age (years ± SD) | 63 ± 12 | 61 ± 13 | 64 ± 13 | 60 ± 14 | <0.01 | 62 ± 13 |

| Male (%) | 125 (81.2%) | 21 (84.0%) | 403 (76.2%) | 209 (69.9%) | 0.03 | 758 (75.3%) |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 129 (92.8%) | 22 (100%) | 393 (81.7%) | 229 (81.5%) | <0.01 | 773 (83.7%) |

| Hepatitis | <0.001 | |||||

| B only (%) | 8 (6.0%) | 1 (6.3%) | 42 (8.5%) | 30 (11.7%) | 81 (9.0%) | |

| C only (%) | 51 (38.1%) | 10 (62.5%) | 119 (24.0%) | 97 (37.9%) | 277 (30.7%) | |

| B & C (%) | 19 (14.2%) | 0 (0%) | 56 (11.3%) | 32 (12.5%) | 107 (11.9%) | |

| No viral hepatitis (%)b | 56 (41.8%) | 5 (31.3%) | 278 (56.2%) | 97 (37.9%) | 436 (48.4%) | |

| Child–Pugh | <0.001 | |||||

| A (%) | 44 (31.9%) | 6 (27.3%) | 388 (73.6%) | 207 (68.5%) | 645 (65.2%) | |

| B (%) | 78 (56.5%) | 13 (59.1%) | 135 (25.6%) | 80 (26.5%) | 306 (30.9%) | |

| C (%) | 16 (11.6%) | 3 (13.6%) | 4 (0.8%) | 15 (5.0%) | 38 (3.8%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.861 | |||||

| Caucasian (%) | 127 (86.4%) | 21 (84.0%) | 463 (88.2%) | 259 (86.6%) | 870 (87.3%) | |

| African American (%) | 15 (10.2%) | 3 (12.0%) | 43 (8.2%) | 26 (8.7%) | 87 (8.7%) | |

| Asian (%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (4.0%) | 11 (2.1%) | 8 (2.7%) | 21 (2.1%) | |

| Other (%) | 4 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (1.5%) | 6 (2.0%) | 18 (1.8%) | |

Percentages presented are only for patients with available data.

Patients with a negative screen for HBV and HCV.

NT, no treatment; ST, systemic therapy; HAT, hepatic artery-based therapy; SI, surgical intervention.

Clinical laboratory values at initial evaluation were analysed. Median bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine and platelets were within normal limits. However, median aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and AFP were increased. Median AST was 65 U/L with an interquartile range (IQR) of 75 U/L; median alanine transaminase (ALT) was 51 (IQR 44) U/L; median alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was 145.5 (124) U/L; median AFP was 51 (1301) ng/mL. Considering patients with available AFP data, 346 (40.0%) had a normal AFP (<20 ng/mL), 228 (26.4%) had an AFP ≥ 20 ng/mL but <400 ng/mL and 291 (33.6%) had an AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL. Median AFP was significantly different between treatment groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test (P < 0.001), with the SI group having the lowest median AFP of 13 (165.5) ng/mL.

Comparisons were made before and after the MELD criteria changed in March 2003 to grant priority points to patients with HCC.47 Patient characteristics and treatments received over these time periods are shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics by pre-current model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) (until 03/03) and current MELD eras

| Pre-current MELD Era | Current MELD Era | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 293 | 717 | |

| Age (years) | 62 ± 15 | 63 ± 12 | 0.883 |

| Male (%) | 220 (75.1%) | 538 (75.4%) | 0.930 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 218 (77.3%) | 555 (86.6%) | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis | 0.01 | ||

| B only (%) | 26 (9.4%) | 55 (8.8%) | |

| C only (%) | 73 (26.3%) | 204 (32.7%) | |

| B & C (%) | 24 (8.6%) | 83 (13.3%) | |

| No hepatitis (%) | 155 (55.8%) | 281 (45.1%) | |

| Child–Pugh | 0.889 | ||

| A (%) | 191 (66.1%) | 454 (64.9%) | |

| B (%) | 88 (30.4%) | 218 (31.1%) | |

| C (%) | 10 (3.5%) | 28 (4.0%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.373 | ||

| Caucasian (%) | 254 (87.6%) | 616 (87.3%) | |

| African American (%) | 21 (7.2%) | 66 (9.3%) | |

| Asian (%) | 9 (3.1%) | 12 (1.7%) | |

| Other (%) | 6 (2.1%) | 12 (1.7%) | |

Table 3.

Treatment trends based pre-current model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) (until 03/03) and current MELD eras

| Pre-current MELD era | Current MELD era | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NT | 50 (17.1%) | 104 (14.5%) | 0.304 |

| ST | 0 (0%) | 25 (3.5%) | <0.01 |

| HAT | 201 (68.6%) | 328 (45.7%) | <0.001 |

| SI | 42 (14.3%) | 260 (36.3%) | <0.001 |

| SI subgroups | |||

| RFA | 9 (3.1%) | 44 (6.1%) | <0.05 |

| Resection | 10 (3.4%) | 113 (15.8%) | <0.001 |

| Transplant | 23 (7.8%) | 103 (14.2%) | <0.01 |

NT, no treatment; ST, systemic therapy; HAT, hepatic artery-based therapy; SI, surgical intervention; RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

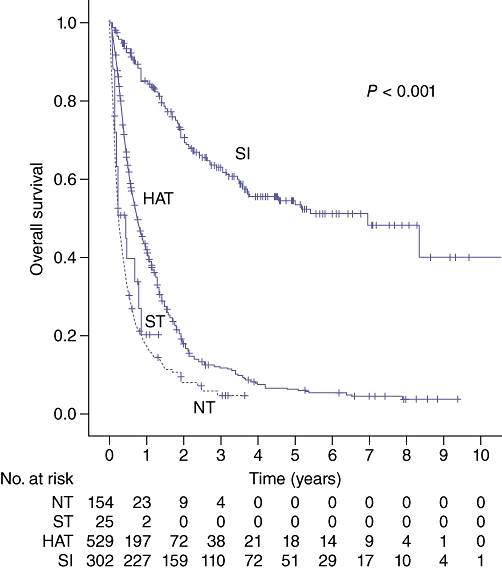

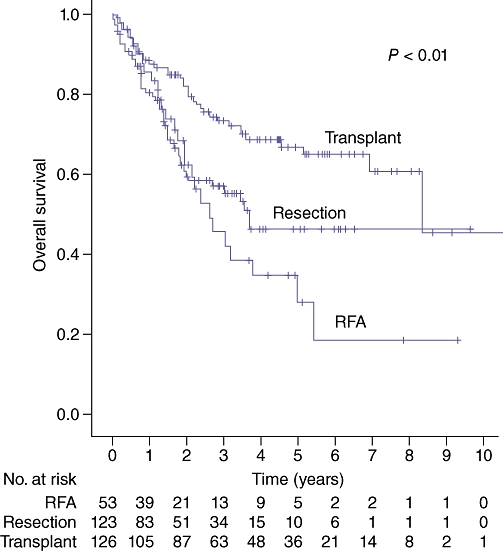

Median 1-, 3- and 5-year survival based on treatment modality is shown in Table 4, with Kaplan–Meier analysis shown in Fig. 2. The SI group was broken down into subgroups of radiofrequency ablation (RFA), resection and transplantation; survival is summarized in Table 5 and Fig. 3.

Table 4.

Actuarial survival based on treatment modality

| 1 year (%) | 3 years (%) | 5 years (%) | Median survival (months, 95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT | 17 | 5 | 0 | 2.8 (1.9–3.8) |

| ST | 23 | 0 | 0 | 5.6 (2.5–8.6)b |

| HAT | 42 | 12 | 6 | 8.8 (7.5–10.1)c |

| SI | 85 | 63 | 54 | 83.5 (51.6–115.4)c |

CI, confidence interval; NT, no treatment; ST, systemic therapy; HAT, hepatic artery-based therapy; SI, surgical intervention.

Median survival determined using the Kaplan–Meier method.

No significant difference in survival compared to no treatment (P = 0.309).

Significant difference in survival compared to no treatment (P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Survival by treatment modality. NT, no treatment; ST, systemic therapy; HAT, hepatic artery-based therapy; SI, surgical intervention

Table 5.

Actuarial survival based on treatment modality (SI group)

| 1 year (%) | 3 years (%) | 5 years (%) | Median survival (months, 95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFA (n = 53) | 86 | 47 | 36 | 31.6 (20.1–43.1)b |

| Resection (n = 123) | 81 | 57 | 47 | 44.5b,c |

| Transplant (n = 126) | 89 | 73 | 66 | 100.3b |

CI, confidence interval; RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

Median survival determined using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Significant difference in survival compared with no treatment (P < 0.001).

No significant difference in survival compared with RFA (P = 0.404).

Figure 3.

Survival by surgical intervention. RFA, radiofrequency ablation

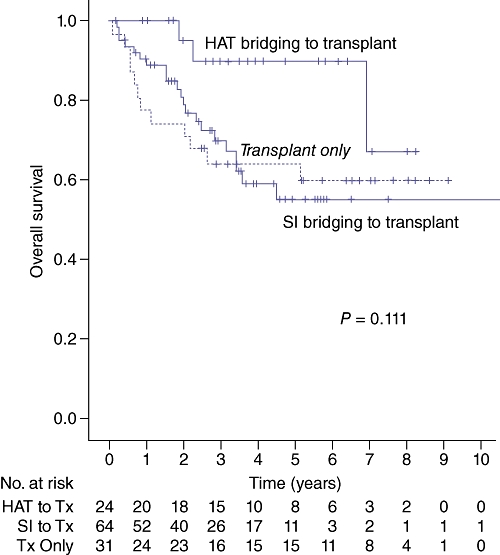

Survival based on the bridging therapy to transplant is summarized in Fig. 4. The mean survival was 7.6 years for transplanted patients with a prior RFA or resection (n = 64), 7.4 years for transplanted patients with prior TACE or Y90 (n = 24) and 6.1 years for patients transplanted with no prior bridging therapy (n = 31), but these differences in survival were not significant (P = 0.111).

Figure 4.

Survival by bridging therapy to transplant. HAT bridging to transplant included TACE and Y90. SI bridging to transplant included radiofrequency ablation and liver resection. HAT, hepatic artery-based therapy; SI, surgical intervention

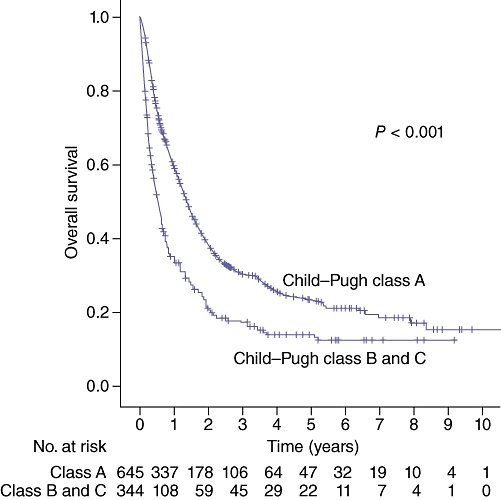

Patients were compared using Child–Pugh class at presentation to assess the impact of severity of cirrhosis on survival. Median survival was 16.6 months for patients with Child–Pugh class A (n = 645) versus 6.6 months for patients with Child–Pugh classes B or C (n = 344) (P < 0.001), shown in Fig. 5. Child–Pugh class similarly determined survival within treatment groups. For NT patients, median survival was 4.6 months for class A (n = 44) and 2.0 months for classes B or C (n = 94) (P < 0.01). For HAT patients, median survival was 11.2 months for class A (n = 388) and 5.2 months for classes B or C (n = 139) (P < 0.001). For SI patients, median survival was 100.3 months for class A (n = 207) and 41.4 months for classes B or C (n = 97) (P = 0.01).

Figure 5.

Survival by Child–Pugh classification

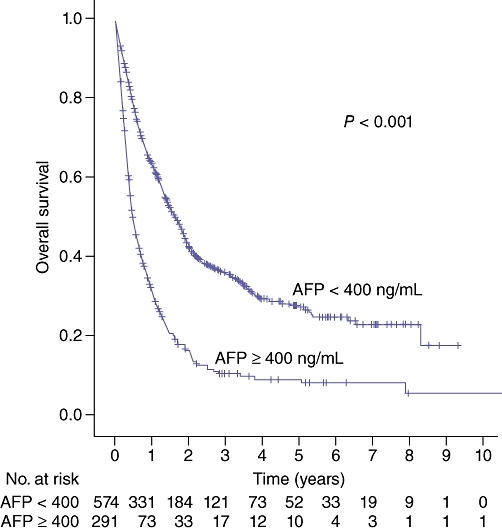

The prognostic value of AFP was assessed using a 400 ng/mL cutoff. Median survival was 20.0 months for all patients with an AFP level below the cutoff (<400 ng/mL) (n = 574) and only 5.8 months for all patients above the cutoff (≥400 ng/mL) (n = 291) (P < 0.001), shown in Fig. 6. This trend was the same within treatment groups. For NT patients, median survival was 3.6 months when AFP was below the cutoff (n = 56) and 1.6 months when AFP was above the cutoff (n = 29) (P < 0.01). For HAT patients, median survival was 14.9 months when AFP was below the cutoff (n = 289) and 4.8 months when AFP was above the cutoff (n = 203) (P < 0.001). For SI patients, there was a longer survival of 100.3 months when AFP was below the cutoff (n = 220) versus 34.2 months when AFP was above the cutoff (n = 53), but this was not significant (P = 0.107).

Figure 6.

Survival by alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level (400 ng/mL cutoff)

Analysis was performed for patients with viral hepatitis. Patients with HBV (n = 81) had a median survival of 12.0 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 6.5–17.5 months] which was not significantly different (P = 0.640) compared with patients with HCV, concomitant HBV and HCV, and no underlying hepatitis [survival of 10.3 (6.8–13.8), 10.5 (4.4–16.7), 13.2 (10.6–15.8) months and n = 277, 107, 436, respectively]. However, hepatitis type was significant when only considering patients who received a liver resection; median survival was 41.9 months for the patients with HBV (n = 13) versus 22.4 months for the patients with HCV (n = 25) (P < 0.05). The presence of cirrhosis differed between these resection groups: 9 (69%) patients with HBV had cirrhosis whereas all 25 (100%) patients with HCV had cirrhosis.

Univariate analysis for prognostic factors found age (P = 0.041), gender (P < 0.001), AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL (P < 0.001), Child–Pugh classification (P < 0.001), cirrhosis (P = 0.002) and treatment modality (P < 0.001) to be significant predictors of survival. Multivariate analysis shows treatment modality to be a robust predictor of survival (P < 0.001, χ2 = 460) after adjusting for significant predictors of survival by univariate analysis (Table 6).

Table 6.

Clinical predictors of survival based on multivariate analysis

| Predictor | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.004 | {0.997–1.0} | 0.320 |

| Gender | 1.325 | {1.071–1.640} | <0.01 |

| Child–Pugh (A vs. B/C) | 0.584 | {0.487–0.700} | <0.001 |

| AFP (<400 vs. ≥400) | 0.427 | {0.358–0.509} | <0.001 |

| Cirrhosis | 1.127 | {0.881–1.440} | 0.342 |

| Treatment modalitya | 0.598 | {0.560–0.638} | <0.001 |

Six treatments were compared (the SI group was subdivided to RFA, resection and transplantation).

CI, confidence interval; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein.

Discussion

HCC is a common cause of cancer-related death worldwide, with a steadily increasing incidence in the United States.3 The management of HCC has evolved over the past two decades along with a better understanding of HCC tumour biology and advancements in therapeutic modalities. Nevertheless, the management of HCC varies widely depending on the extent of disease, level of hepatic functional reserve and overall functional status of patients. While the need exists for an integrated comprehensive treatment approach, HCC is a complex disease with constantly changing management. There is also no universal system for staging HCC. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Center (BCLC) staging system has gained widespread acceptance over TNM classification as it goes beyond pathological staging to incorporate functional liver status and cancer-related symptoms.23,48,49 Most large published series describing presentation and treatment of HCC are from Asian centres, which account for more than 75% of the new HCC diagnoses made globally each year.37–43,50 In Asia, there is a variety of underlying liver diseases, with HBV as the main aetiological factor.42 This is in contrast to the United States, where HCV is the predominant cause of HCC. In most Asia-Pacific countries, chronic HBV infection is the cause for 75–80% of HCC; Japan, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand are exceptions with a higher prevalence of HCV infection.51 Similar to the United States, the management of HCC has a multimodal approach, with the utilization of loco-regional treatment such as TACE and Y90 in downstaging or bridging non-resectable patients to salvage liver surgery or transplantation.31,40,52

This study is significant as it describes the presentation, management and outcomes of patients with HCC at a large Western Center. Most patients evaluated were Caucasian males with underlying cirrhosis and viral hepatitis. Comparing the first 3 and last 6 years of the study, HCV incidence increased from 34.9% to 45% (P < 0.001), consistent with the national trends.3 More patients had underlying cirrhosis over these subsequent time periods (77.3% to 86.6%, P < 0.01).

Multivariate analysis found treatment modality to be a robust predictor of survival after adjusting for other significant factors. Less than one-third of patients were managed with SI; liver resection and transplantation were treatments for 12.1% and 12.5% of patients, respectively. It is well recognized that liver resection and liver transplantation are the primary curative therapeutic options for HCC, yielding a 5-year survival of 60–70% in well-selected patients.7 However, as the BCLC staging system attempted to address, most patients are not candidates for liver resection as a result of extensive disease at presentation, diminished underlying liver function and poor patient performance status.23,48,49 In the present study, most patients receiving SI (68.5%) were Child–Pugh class A whereas only 5% were Child–Pugh class C. This illustrates the selection bias when considering SI as a treatment.

Interestingly, SI increased significantly between the two study periods from 14.3% to 36.3% (P < 0.001). This increase is likely multifactorial. Outreach programmes and education for primary care and community physicians led to improved surveillance and detection of high-risk patients, resulting in increased early referring patterns to our tertiary care centre.44 Liver transplantation was a more frequent treatment (7.8% to 14.2%, P < 0.01) for patients with HCC when the new MELD scoring system granted bonus points to patients with stage II HCC and liver cirrhosis. The increase in liver resections (3.4% to 15.8%, P < 0.001) had the largest impact on the overall increase in SI. Resection criteria were generally broadened because of several factors: improvements in surgical techniques with new coagulation devices, a better understanding of intricate liver anatomy, enhanced management of hepatic cirrhosis, improved anaesthetic care and an integrated post-operative care approach. It is interesting and unexpected that the overall frequencies of resection and transplantation were similar. However, comparing between the two MELD eras, the increase in liver resection exceeds that of transplantation. At this point, it is difficult to predict if the frequency of liver resection will continue to increase and surpass liver transplantation. With limited organ availability and advancements in peri-operative care, it is likely that liver resection will be a leading curative option. The doubling in rate of RFA over the two study periods (3.1% to 6.1%, P < 0.05) is as a result of its two unique and growing applications. RFA was utilized to treat non-surgical candidates with early stage HCC and poor underlying liver functional reserve or difficult-to-resect tumour location. It was also used as bridging therapy for patients who were awaiting transplantation.44 Our experience showed that 17.9% of transplanted patients were bridged with RFA, compared with 4.7% bridged with liver resection. There appears to be improved survival with liver resection alone compared with RFA alone (44.5 versus 31.6 months) but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.404). Several studies have similarly described bridging to transplant with RFA and demonstrated comparable survival benefits of using RFA and liver resection for HCC < 3 cm in diameter.22,33,53

Mirroring the selection bias with SI for well-preserved hepatic function, most patients who received NT (78.1%) and ST (72.7%) were Child–Pugh class B or C. For patients with advanced HCC, cytotoxic systemic chemotherapy has failed to demonstrate an overall survival benefit.54 A large randomized prospective trial demonstrated that sorafenib, a targeted molecular therapy functioning as a multikinase inhibitor, yielded a median survival of 10.7 months compared with 7.9 months for the placebo group.34,55 The overall risk of death was also decreased by 31%.34 A randomized Asia-Pacific study showed similar results.35 Subsequently, guidelines currently recommend sorafenib as a first-line treatment in patients with unresectable HCC who are not candidates for TACE or ablative therapy.34,36 However, our study shows the median survival of ST was only 2.8 months more than NT group, which was not statistically significant (P = 0.309). This was most probably because of a small sample size from an underestimation of the ST group. Our analysis reports that less than 3% of patients received systemic sorafenib. This underestimation results from management of ST patients by their medical oncologists. As these outpatient records were not recorded in the UPMC LCC registry, all patients with ST were not captured – a limitation of our retrospective study.

Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have examined arterial embolization (including bland embolization and TACE) and demonstrated significant survival advantages compared with conservative treatment.16,18,56–58 TACE has subsequently been included in treatment armamentarium for HCC. Additionally, Y90 radioembolization has been used as loco-regional therapy in patients with unresectable disease and preserved liver function. Response rates of 39–47% have been reported.46,59 A two-cohort study also demonstrated the short-term outcomes of Y90 to be equivalent to TACE in well-selected patients.21 In the present study, HAT was utilized for 63.3% of all patients. TACE and Y90 represented more than 70% and less than 30% of HAT, respectively. Interestingly, 36.4% of all SI patients also received HAT. While HAT was performed for more than 20% of patients undergoing RFA and liver resection, it was performed for more than 50% of patients receiving a transplant.

Liver transplantation has the longest median survival (100.3 months) of all treatment modalities. At the UPMC LCC, all patients with HCC were presented at a multidisciplinary tumour conference and were referred for liver transplant evaluation based on the Milan criteria. Even after the initial implementation of the MELD score for transplant allocation in 2002–2003, there are prolonged waiting times as a result of organ shortage. Therefore, liver resection is still a frequent option for patients who recently became transplant candidates. After subsequent addition of 22 bonus points for patients with stage II HCC, there was a continued increase in competition for donor organs, causing further growth of waiting times. This lead to the increased use of minimally invasive bridging therapy such as laparoscopic RFA. Multiple bridging therapies to transplant were employed in an effort to downstage the tumour to allow for listing and to delay tumour progression to prevent dropouts while awaiting transplantation.22–25,56 The American Association for the Study of the Liver Diseases guidelines recommended the use of RFA and TACE if the expected waiting time is longer than 6 months.60,61 However, there have been no randomized controlled trials to investigate different bridging treatment modalities for these patients.60,62 In the present study, the majority of patients who underwent liver transplantation received prior therapy (75.4%) including HAT in 56.3%, RFA in 15.1% and liver resection in 4.0%. The median survival for bridging to transplant with SI and HAT were 7.6 and 7.4 months, respectively, whereas transplant alone was 6.1 months; however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.111). These outcomes of bridging therapy before transplant are consistent with other published reports.22,24 The limitation of cadaveric livers remains the most significant barrier in the management of HCC, especially in Asia where the availability of organs is severely limited. There is a great interest in living related liver transplantation to compensate for this limitation, and there is an ongoing debate regarding expansion of the Milan criteria for this modality.63

The majority of patients in this series had underlying cirrhosis and viral hepatitis, predominately Child–Pugh class A (65.2% of all cirrhotic patients) and HCV (30.7% of patients with recorded hepatitis screening). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis demonstrated survival advantages in patients with Child–Pugh class A when compared with Child–Pugh class B or C. This is consistent literature which demonstrated that Child–Pugh classification was one of the most significant factors in predicting outcome.64 Interestingly, there was no difference in survival between patients with underlying HBV, HCV, and concomitant HBV and HCV. However, in the context of survival after liver resection, HBV had a statistically significant better survival compared with HCV (41.9 vs. 22.4 months, P < 0.05). Roayaie et al. also retrospectively compared outcomes of liver resection for HCC in 43 HBV and 121 HCV patients.65 The 5-year disease-free survival was significantly higher for HBV patients compared with HCV patients after liver resection (49% vs. 7%, P = 0.048).65 This difference could be because of poorer hepatic functional reserve and a greater association of cirrhosis with HCV.

The role of AFP as a diagnostic and prognostic factor remains controversial.66 AFP can be non-specifically elevated with cirrhosis, alcoholic liver disease and viral hepatitis.67 Therefore, the level of AFP in patients with HCC can vary according to the aetiology of underlying liver pathology. No broad consensus exists regarding the use of AFP as a prognostic factor.66,67 However, the present study demonstrates a significantly longer survival for patients with an AFP < 400 ng/mL compared with patients with an AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL (20 vs. 5.8 months, P < 0.001). This significant survival benefit was observed regardless of treatment modality. Univariate analysis also implicates the prognostic value of AFP in patients with HCC.

The management of HCC has evolved significantly over the past decade with evolving roles of loco-regional therapy and transplantation in patients with HCC. Nevertheless, the only curative options are liver resection and liver transplantation. Thus, it is of great importance for community healthcare providers to work closely with a tertiary care centre. A primary goal is public education based on current evidence-based recommendations regarding risk reduction, prevention, vaccination and screening protocols in patients with a high risk for HCC. Once the patient is diagnosed with HCC, timely referral to a tertiary care centre is essential.

The present study reports a large current series of HCC patients evaluated at a Western Centre. While inherent treatment biases limit the strength of conclusions that can be made, this retrospective study shows that proper patient selection can improve outcomes by tailoring therapy to tumour pathology and hepatic function. As we learn more about HCC molecular markers and tumour biology, there is the potential for further optimization of management. Future studies should address the promise of identifying the optimal therapeutic approaches based on a tumor's molecular biology.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Bosch FX, Ribes J, Diaz M, Cleries R. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology. 2004;5(Suppl. 1):S5–S16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:533–543. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745–750. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mor E, Kaspa RT, Sheiner P, Schwartz M. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with cirrhosis in the era of liver transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:643–653. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-8-199810150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumberg BS, Larouze B, London WT, Werner B, Hesser JE, Millman I, et al. The relation of infection with the hepatitis B agent to primary hepatic carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1975;81:669–682. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukuma H, Hiyama T, Tanaka S, Nakao M, Yabuuchi T, Kitamura T, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1797–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306243282501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J. Intention-to-treat analysis of surgical treatment for early hepatocellular carcinoma: resection versus transplantation. Hepatology. 1999;30:1434–1440. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonas S, Herrmann M, Rayes N, Berg T, Radke C, Tullius S, et al. Survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis according to the underlying liver disease. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:3444–3445. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bismuth H, Majno PE, Adam R. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:311–322. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bismuth H, Chiche L, Adam R, Castaing D, Diamond T, Dennison A. Liver resection versus transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Ann Surg. 1993;218:145–151. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199308000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llovet JM, Bruix J, Fuster J, Castells A, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Grande L, et al. Liver transplantation for small hepatocellular carcinoma: the tumor-node-metastasis classification does not have prognostic power. Hepatology. 1998;27:1572–1577. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts JP. Tumor surveillance-what can and should be done? Screening for recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11(Suppl. 2):S45–S46. doi: 10.1002/lt.20605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;5(Suppl. 1):S27–S34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charpentier KP, Cheah YL, Machan JT, Miner T, Morrissey P, Monaco A. Intention to treat survival following liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma within a donor service area. HPB (Oxford) 2008;10:412–415. doi: 10.1080/13651820802392320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camma C, Schepis F, Orlando A, Albanese M, Shahied L, Trevisani F, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiology. 2002;224:47–54. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2241011262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewandowski RJ, Kulik LM, Riaz A, Senthilnathan S, Mulcahy MF, Ryu RK, et al. A comparative analysis of transarterial downstaging for hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization versus radioembolization. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1920–1928. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Kulik L, Wang E, Riaz A, Ryu RK, et al. Radioembolization results in longer time-to-progression and reduced toxicity compared with chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:497–507. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.049. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carr BI, Kondragunta V, Buch SC, Branch RA. Therapeutic equivalence in survival for hepatic arterial chemoembolization and yttrium 90 microsphere treatments in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a two-cohort study. Cancer. 2010;116:1305–1314. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heckman JT, Devera MB, Marsh JW, Fontes P, Amesur NB, Holloway SE, et al. Bridging locoregional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma prior to liver transplantation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3169–3177. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahbari NN, Mehrabi A, Mollberg NM, Muller SA, Koch M, Buchler MW, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: current management and perspectives for the future. Ann Surg. 2011;253:453–469. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820d944f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman WC, Majella Doyle MB, Stuart JE, Vachharajani N, Crippin JS, Anderson CD, et al. Outcomes of neoadjuvant transarterial chemoembolization to downstage hepatocellular carcinoma before liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2008;248:617–625. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818a07d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravaioli M, Grazi GL, Piscaglia F, Trevisani F, Cescon M, Ercolani G, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: results of down-staging in patients initially outside the Milan selection criteria. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2547–2557. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sala M, Llovet JM, Vilana R, Bianchi L, Sole M, Ayuso C, et al. Initial response to percutaneous ablation predicts survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2004;40:1352–1360. doi: 10.1002/hep.20465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiina S, Tagawa K, Niwa Y, Unuma T, Komatsu Y, Yoshiura K, et al. Percutaneous ethanol injection therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: results in 146 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:1023–1028. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.5.7682378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livraghi T, Giorgio A, Marin G, Salmi A, de Sio I, Bolondi L, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis in 746 patients: long-term results of percutaneous ethanol injection. Radiology. 1995;197:101–108. doi: 10.1148/radiology.197.1.7568806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lencioni RA, Allgaier HP, Cioni D, Olschewski M, Deibert P, Crocetti L, et al. Small hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: randomized comparison of radio-frequency thermal ablation versus percutaneous ethanol injection. Radiology. 2003;228:235–240. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2281020718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng Y, Guo RP, Liang HH, Zhang YQ, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and partial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;243:321–328. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho YK, Kim JK, Kim MY, Rhim H, Han JK. Systematic review of randomized trials for hepatocellular carcinoma treated with percutaneous ablation therapies. Hepatology. 2009;49:453–459. doi: 10.1002/hep.22648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin SM, Lin CJ, Lin CC, Hsu CW, Chen YC. Radiofrequency ablation improves prognosis compared with ethanol injection for hepatocellular carcinoma < or = 4 cm. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1714–1723. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiina S, Teratani T, Obi S, Sato S, Tateishi R, Fujishima T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation with ethanol injection for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:122–130. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruix J, Llovet JM. Two decades of advances in hepatocellular carcinoma research. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:1–2. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan ST, Mau Lo C, Poon RT, Yeung C, Leung Liu C, Yuen WK, et al. Continuous improvement of survival outcomes of resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 20-year experience. Ann Surg. 2011;253:745–758. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182111195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mok KT, Wang BW, Lo GH, Liang HL, Liu SI, Chou NH, et al. Multimodality management of hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takano S, Watanabe Y, Ohishi H, Kono S, Nakamura M, Kubota N, et al. Multimodality treatment for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a single institution retrospective series. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:67–72. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, Chen PJ, Lin SM, Yoshida H, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:439–474. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9165-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song P, Tang W, Tamura S, Hasegawa K, Sugawara Y, Dong J, et al. The management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia: a guideline combining quantitative and qualitative evaluation. Biosci Trends. 2010;4:283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poon D, Anderson BO, Chen LT, Tanaka K, Lau WY, Van Cutsem E, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia: consensus statement from the Asian Oncology Summit 2009. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1111–1118. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arii S, Sata M, Sakamoto M, Shimada M, Kumada T, Shiina S, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: report of Consensus Meeting in the 45th Annual Meeting of the Japan Society of Hepatology (2009) Hepatol Res. 2010;40:667–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2010.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geller DA, Tsung A, Marsh JW, Dvorchik I, Gamblin TC, Carr BI. Outcome of 1000 liver cancer patients evaluated at the UPMC Liver Cancer Center. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ebied OM, Federle MP, Carr BI, Pealer KM, Li W, Amesur N, et al. Evaluation of responses to chemoembolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:1042–1050. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carr BI. Hepatic arterial 90Yttrium glass microspheres (Therasphere) for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: interim safety and survival data on 65 patients. Liver Transpl. 2004;2(Suppl. 1):S107–S110. doi: 10.1002/lt.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trotter JF, Osgood MJ. MELD scores of liver transplant recipients according to size of waiting list: impact of organ allocation and patient outcomes. JAMA. 2004;291:1871–1874. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Barrat A, Askari F, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL, et al. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of 7 staging systems in an American cohort. Hepatology. 2005;41:707–716. doi: 10.1002/hep.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grieco A, Pompili M, Caminiti G, Miele L, Covino M, Alfei B, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with early-intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing non-surgical therapy: comparison of Okuda, CLIP, and BCLC staging systems in a single Italian centre. Gut. 2005;54:411–418. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.048124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yeh CN, Lee WC, Chen MF. Hepatic resection and prognosis for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm: two decades of experience at Chang Gung memorial hospital. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:1070–1076. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuen MF, Hou JL, Chutaputti A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lau WY, Lai EC. Salvage surgery following downstaging of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma–a strategy to increase resectability. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3301–3309. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lau WY, Lai EC. The current role of radiofrequency ablation in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2009;249:20–25. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818eec29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsu C, Huang CL, Hsu HC, Lee PH, Wang SJ, Cheng AL. HER-2/neu overexpression is rare in hepatocellular carcinoma and not predictive of anti-HER-2/neu regulation of cell growth and chemosensitivity. Cancer. 2002;94:415–420. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilhelm SM, Adnane L, Newell P, Villanueva A, Llovet JM, Lynch M. Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both Raf and VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3129–3140. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, Liu CL, Lam CM, Poon RT, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164–1171. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bruix J, Sala M, Llovet JM. Chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;5(Suppl. 1):S179–S188. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takayasu K, Arii S, Ikai I, Omata M, Okita K, Ichida T, et al. Prospective cohort study of transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in 8510 patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:461–469. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Atassi B, Gordon SC, Gates VL, Barakat O, et al. Treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with use of 90Y microspheres (TheraSphere): safety, tumor response, and survival. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:1627–1639. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000184594.01661.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–1236. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Capussotti L, Ferrero A, Vigano L, Polastri R, Tabone M. Liver resection for HCC with cirrhosis: surgical perspectives out of EASL/AASLD guidelines. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cabibbo G, Latteri F, Antonucci M, Craxi A. Multimodal approaches to the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:159–169. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee HS. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: the controversies continue. Dig Dis. 2007;25:296–298. doi: 10.1159/000106907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Christians KK, Pitt HA, Rilling WS, Franco J, Quiroz FA, Adams MB, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: multimodality management. Surgery. 2001;130:554–559. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.117106. discussion 9–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roayaie S, Haim MB, Emre S, Fishbein TM, Sheiner PA, Miller CM, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B versus hepatitis C: a western experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:764–770. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0764-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Farinati F, Marino D, De Giorgio M, Baldan A, Cantarini M, Cursaro C, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic role of alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma: both or neither? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:524–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim HS, Park JW, Jang JS, Kim HJ, Shin WG, Kim KH, et al. Prognostic values of alpha-fetoprotein and protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:482–488. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318182015a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]