Abstract

Objectives

To explore regional variations in donation of cadaveric solid organs and tissues across the four devolved health administrations of the UK (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland).

Design

A secondary analysis of databases from NHS Blood & Transplant (1990–2009) and from the National Organ Procurement Service for the Republic of Ireland, Eurotransplant International Foundation and Scandiatransplant.

Results

After adjusting for time, statistically significant differences were found among the four regions (p<0.001) for liver donations. The only exceptions were between England and Scotland and between Wales and Northern Ireland where the differences were not significant following a Bonferroni correction (p>0.008). England had significantly fewer heart donations than both Wales (p<0.001) and Northern Ireland (p=0.005). There were no significant differences among the four regions for lung donations. Regional variations in kidney and corneal donations were moderated by time. Northern Ireland, however, has had consistently lower corneal donation rates than the other three regions.

Conclusion

Organ donation rates over the last two decades vary in the four UK regions, and this variation depends on the type of organ donated. Further exploration of underlying factors, organisational issues, practices and attitudes to organ donation in the four regions of the UK, taking into account findings from EU countries with varying approaches to presumed consent, needs to be undertaken before such legislation is introduced across the UK.

Article summary

Article focus

To investigate organ donation of cadaveric solid organs and tissues across the four devolved health administrations of the UK and how they vary with time.

To consider reasons for regional variations and those related to organ type, drawing on regional differences in culture and practice and on findings in other EU countries.

Key messages

Organ donation and registration rates vary with time across the four regions of UK.

Heart and liver donations are highest in Wales and Northern Ireland.

The significance of regional variations on kidney and corneal donation rates is moderated by the effect of changes over time; Northern Ireland consistently has the lowest corneal donation rate.

The reasons for regional variations require further investigation as well as comparisons with practices and attitudes in other EU states.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this article are: (1) its novelty, as this is the first article that has analysed data across the UK and shown patterns in donation rates in the four regions over the last two decades; (2) its timeliness given the shortfall in organ donations, the continuing debate about presumed consent and its importance in investigating regional differences.

The limitation of this article is that data from other EU countries, for the entire time period investigated, were not available.

Introduction

Approximately 80–90% of the UK population support the principle of organ donation,1 yet only 29% of the population carry an organ donor card.2 Despite advances in transplantation medicine, organ shortage is the single most limiting factor preventing potential recipients from receiving the benefits of transplantation.3 If the overwhelming support for organ donation could be directly translated into a willingness to donate, this should bode well for a presumed consent system (allowing organs to be used for transplantation unless the individual has explicitly objected). However, interpretation of these findings is far from simple. This paper presents an analysis of data of organ donation and registration in the four regions of the UK for five organ types, kidney, liver, heart, lung and cornea, in order to determine whether significant differences exist across the four regions and whether these vary depending on the organ. Any variations may be influenced by factors that could subsequently affect whether or not a presumed consent system, especially one that included the consent of relatives, were to be successful or whether it may create regional inequalities. Comparisons are made with European nations that have adopted presumed consent as well as with those that have not, in order to see whether such factors may be discernible.

Methods

Information about all organ donations and registration in the four regions of the UK, England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, was obtained from NHS Blood & Transplant for all available years, from 1990 to 2009. Data from other European nations were provided from the National Organ Procurement Service for Ireland,4 Eurotransplant International Foundation5 and Scandiatransplant (Scandiatransplant, personal communication, 2011). Statistical analyses were carried out using Poisson regression (SPSS version 17). Bonferroni corrections were used to control for Type I errors when making inter-regional comparisons.

Results and discussion

Regional variations in registration and donation

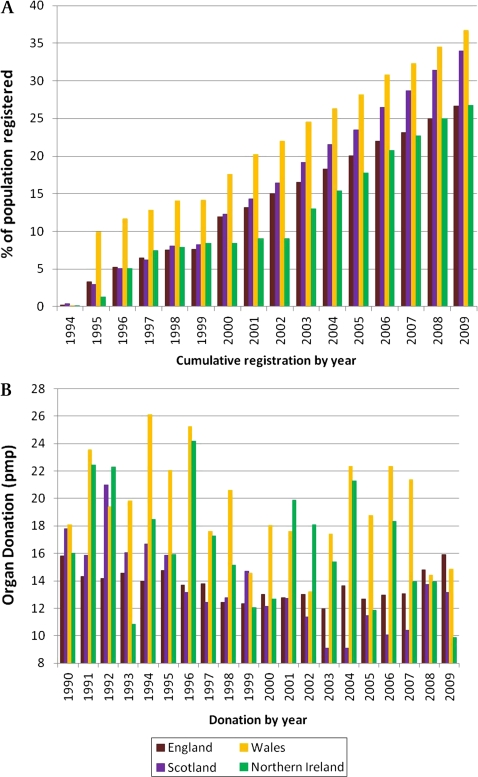

The UK currently operates a system of informed consent requiring individuals who wish to donate, to formally register their intention on a centralised register. Figure 1A shows that since the organ donor register was first launched in 1994, Wales has consistently outperformed other parts of the UK in terms of the percentage of population registered, with Scotland in second position, England third and Northern Ireland last. (A caveat is that although records are updated periodically to remove those who have died subsequent to being registered, organ donor registration rates may still include some entries of deceased individuals. This should not, however, affect regional variations.)

Figure 1.

(A) Organ-donor registration rates in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland 1994–2009. (B) Organ-donation rates in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland 1990–2009. pmp, per million population.

When the registration rates are compared with donation rates, the trends are somewhat different. The rate of organ donation is consistently higher in Wales than the UK average for the majority of the last 20 years (figure 1B). Donation rates in Northern Ireland are the second highest, achieving rates higher than the UK average in 13 of those years, with Scotland achieving this in 6 years and England capable of achieving this in only 3 years. Thus, while registration and donation are both highest in Wales, among other parts of the UK registration and donation do not follow similar trends. In Northern Ireland, for example, where willingness to register as an organ donor is lower than in any other UK region, the organ-donation rate is generally higher than in England or Scotland. It is also notable that while England exhibits the least variation in organ donation over the last two decades, Scotland shows an overall decrease in donation with trends in Wales and Northern Ireland varying from year to year, with the greatest fluctuations in the latter.

Variations in donation according to organ type

Masked by general variations in donation are the figures for individual organs. Table 1 shows the rate of donation for each region of the UK for different organs. Poisson regression analyses were carried out on the numbers of organ donations (entries in table 1 × the population for each country in that year expressed in millions) using the ‘Generalized Linear Models’ program in SPSS Version 17. The offset was the natural logarithm of the total population for each country, which varied slightly from year to year. Separate analyses were carried out for each organ because donors may donate more than one organ, and so a single model analysis would violate the assumption of independent observations. Four different models were considered: the intercept-only model, M0, which included no explanatory variables; model M1, which included the explanatory variable year (as well as the intercept); model M2, which included the explanatory variables year and country; and the full or saturated model M3, which includes the explanatory variables year and country, and their interaction. Pairs of models were compared using the differences between their deviance values (ΔD). This statistic is a large-sample χ2 statistic with degrees of freedom equal to the difference between the residual df values for the two models. Model M1 was a statistically significant improvement over model M0, and model M2 was a significant improvement over model M1 (in all cases, the value of ΔD was significant at p<0.001). In the case of liver, lung and heart, model M2 was not statistically significantly different from the saturated model M3. Since the two models have a comparable fit, the former was selected on the grounds that it is the more parsimonious (requires fewer parameters to be estimated). Applying model M2 for the liver, Wales had significantly higher counts than England and Scotland (Wald χ2 90.23, df=1, p<0.001; 65.12, df=1, p<0.001 respectively), and Northern Ireland had significantly higher counts than England and Scotland (Wald χ2 21.34, df=1, p<0.001; 19.04, df=1, p<0.001, respectively). After a Bonferroni correction (six comparisons carried out, original α=0.05, adjusted significance level=0.05/6=0.008) there was no statistically significant difference between England and Scotland, or between Wales and Northern Ireland (Wald χ2 0.506, df=1, p=0.477; 5.76, df=1, p=0.016). For the lung, there were no statistically significant differences between the regions. In the case of the heart, England had significantly fewer donations than Wales and Northern Ireland (Wald χ2 19.86, df=1, p<0.001; 8.06, df=1, p=0.005, respectively). There were no significant differences between Scotland and the other three regions after applying a Bonferroni correction.

Table 1.

UK donor rates (deceased donors per million population) by organ type 1990–2009

| Year | Kidney |

Heart |

Lung |

Liver |

Cornea |

|||||||||||||||

| E | S | W | NI | E | S | W | NI | E | S | W | NI | E | S | W | NI | E | S | W | NI | |

| 1990–1991 | 14.6 | 17.4 | 19.0 | 19.2 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 5.4 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 7.1 | 27.8 | 11.4 | 16.7 | 9.9 |

| 1991–1992 | 13.9 | 14.7 | 21.2 | 25.5 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 6.8 | 5.7 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 12.2 | 14.7 | 29.6 | 12.3 | 29.3 | 14.0 |

| 1992–1993 | 13.7 | 19.4 | 14.4 | 15.3 | 3.8 | 5.7 | 6.3 | 3.8 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.1 | 12.0 | 12.2 | 7.6 | 33.1 | 21.9 | 24.3 | 16.2 |

| 1993–1994 | 12.9 | 17.3 | 17.6 | 10.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 9.8 | 12.0 | 13.5 | 8.9 | 37.5 | 21.0 | 23.9 | 12.7 |

| 1994–1995 | 13.5 | 15.1 | 25.7 | 19.8 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.7 | 11.0 | 18.0 | 12.1 | 37.5 | 21.4 | 28.6 | 15.3 |

| 1995–1996 | 12.8 | 15.1 | 17.6 | 16.6 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 10.9 | 11.4 | 16.7 | 11.5 | 34.5 | 19.7 | 85.4 | 13.4 |

| 1996–1997 | 12.8 | 10.5 | 20.0 | 23.8 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 10.9 | 8.2 | 20.4 | 17.5 | 33.0 | 17.1 | 80.7 | 12.2 |

| 1997–1998 | 11.7 | 12.5 | 18.7 | 16.5 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 11.0 | 10.2 | 18.0 | 14.6 | 26.2 | 14.8 | 48.2 | 5.8 |

| 1998–1999 | 11.0 | 13.7 | 16.2 | 12.1 | 2.4 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 10.5 | 12.0 | 13.2 | 11.5 | 26.0 | 13.1 | 46.9 | 6.0 |

| 1999–2000 | 11.7 | 13.1 | 15.0 | 13.3 | 2.0 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 11.2 | 12.0 | 16.3 | 10.2 | 27.1 | 15.6 | 52.0 | 4.8 |

| 2000–2001 | 11.6 | 9.5 | 13.7 | 12.7 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 11.1 | 9.8 | 14.5 | 12.1 | 30.2 | 16.2 | 31.9 | 7.8 |

| 2001–2002 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 14.5 | 18.7 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 10.5 | 11.4 | 13.2 | 16.3 | 25.1 | 10.4 | 42.3 | 7.8 |

| 2002–2003 | 11.0 | 7.9 | 14.2 | 18.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 11.6 | 10.0 | 14.2 | 16.1 | 25.4 | 12.8 | 51.3 | 7.7 |

| 2003–2004 | 10.7 | 7.7 | 18.8 | 17.2 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 11.1 | 8.7 | 19.6 | 15.4 | 28.5 | 8.9 | 62.1 | 8.9 |

| 2004–2005 | 9.8 | 8.3 | 16.5 | 16.0 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 10.3 | 10.7 | 16.5 | 17.2 | 27.0 | 15.0 | 51.3 | 4.1 |

| 2005–2006 | 9.4 | 5.5 | 14.7 | 10.1 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 10.4 | 8.5 | 14.3 | 10.1 | 31.1 | 12.7 | 26.6 | 8.9 |

| 2006–2007 | 8.5 | 6.5 | 15.2 | 16.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 10.6 | 6.9 | 17.9 | 19.7 | 32.8 | 15.2 | 36.1 | 8.8 |

| 2007–2008 | 7.2 | 4.7 | 9.6 | 8.7 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 10.6 | 8.3 | 14.0 | 10.5 | 34.3 | 18.6 | 27.5 | 4.7 |

| 2008–2009 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 8.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 11.2 | 10.8 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 34.4 | 21.1 | 24.0 | 4.1 |

E, England; NI, Northern Ireland; S, Scotland; W, Wales.

For the cornea and kidney, model M2 was a significantly poorer fit than the saturated model. (There was also substantial overdispersion as indicated by the values of D/df which was not corrected using a negative binomial as an alternative model). These findings suggest that for these organs, the effect of country was moderated by year. For example, in the case of the cornea, the donor rates per million for Scotland and Northern Ireland were quite close in 1991–1992 (12.3 and 14.0 respectively), whereas in 2008–2009, there was a substantial discrepancy (21.1 and 4.1 respectively). Inspection of the Poisson interaction term indicated that the difference between Scotland and Northern Ireland in 2008–2009 (17.0) was significantly greater (p<0.001) than the difference between the two regions in 1991 and 1992.

The results show certain regional differences in donation for four of the organs. With regards to the liver, the Poisson analysis indicated that Wales and Northern Ireland had statistically significantly higher donor rates than England and Scotland. The rate of liver donation has been consistently highest in Wales for the past 20 years, and Northern Ireland has contributed the second-highest rate of donation for most of the years examined. Heart donations were also statistically significantly higher in Wales and Northern Ireland compared with England. With respect to heart donation, in the first decade examined, with the exception of 1995–1996, Wales was the region with the highest overall donation rate until 1998, when it was overtaken by Scotland and/or Northern Ireland. One or both of these regions dominated in heart donations over most of the second decade studied (with the exception of 2003–2004 and 2006–2007 when Wales had the highest donations). The overall rate of heart donations has fallen over the 20-year period for Wales, Scotland and England; Northern Ireland shows fluctuations with no consistent trend.

In contrast to falling heart-donation rates, the rate of lung donation has risen since 1990, with Northern Ireland being the greatest contributor over most of this period. This notwithstanding, there were no statistically significant regional variations in lung donations. It should be noted that lung and heart donations have been very low in number in all regions across all the years compared with other organs, and this may reflect the fact that heart-beating donors, on which heart and most lung transplants depend, have been decreasing for around a decade across the UK.6

Kidney and corneal donations showed significant regional differences, but these were not consistent across the time period investigated, as indicated by the need to add an interaction term to the models. No discernible pattern emerges from the kidney-donation data, although it is perhaps worth noting that for most of the first decade examined, England was the lowest contributor; in the second decade, with the exception of 1 year (2008–2009), the lowest contributions came from Scotland.

The pattern for corneal donations shows a greater consistency for most regions except Wales, which contributed significantly more corneal tissue than the other regions between 1995 and 2005 but subsequently decreased to levels comparable with pre-1995 and with those of England. There is no obvious reason for this trend. Perhaps the most striking picture to emerge from the data shown in table 1 is the low rate of corneal donations in Northern Ireland, particularly when compared with those of England and Wales. Scotland and Northern Ireland were very similar in corneal donations in the early part of the first decade examined, but subsequently the gap increased.

The patterns seen with corneal donations may reflect attitudes based on culture and tradition as well as on lack of awareness of what eye donation involves. In Northern Ireland and, to a lesser extent, in Scotland, the tradition of wakes and burial remains strong. Disfiguring the face of a deceased loved one before burial by removing the eyeballs is unlikely to be accepted.7 There is no eye bank or retrieval centre in Northern Ireland; if such a centre is ever established, the effect of collecting eye tissue on facial appearance will require comprehensive explanation, as studies show that procuring corneal tissue is erroneously considered to be a procedure that leads to disfigurement.7–9 In Wales and England, where over 70% of deaths result in cremations (compared with around 60% of deaths in Scotland and 15% in Northern Ireland),10 the issue of the facial appearance of the deceased may be of less importance. The presence of an eye bank would make it possible to procure corneal tissue locally; however, it has been found that appropriately trained and dedicated staff are the most likely means of increasing corneal donations.11 12 Coordinated organisation and appropriate policies and staff training would also improve consent to donation of other organs.13 14

It should be noted that in addition to differences in rates of donation of different organs, there are variations in their health status and in time limitations permitted for maintaining a status that is suitable for transplantation. For example, in the years 2009 to 2010, an average of 11% of all organs retrieved were not subsequently transplanted.6 This applied particularly to the retrieval of lungs and liver. Although approximately 33% of all corneas recovered during the same period were deemed unsuitable for transplantation,6 the cornea is more viable than the heart and lungs owing to its ability to survive for an extended period of time in appropriate medium before transplantation. A confidential audit of deaths in England and Wales showed that approximately 92% of donors had a suitable cornea for donation, while 65% had a suitable heart for donation, and only 31% had suitable lungs for donation.15

Can parallels be drawn from the EU?

It has been suggested that at least 20–30 deceased donors per million population would be necessary to meet the UK's increasing demands.16 The British Medical Association called for changes in legislation, suggesting a system of presumed consent that allows for objections of relatives.17 The Organ Donation Taskforce was commissioned in 2008 to consider the potential effects of such legislation and concluded that a change to presumed consent at this time was unlikely to increase organ-donation rates, may incur prohibitive costs and could result in a backlash; other factors needed to be considered before introducing legislative change.18

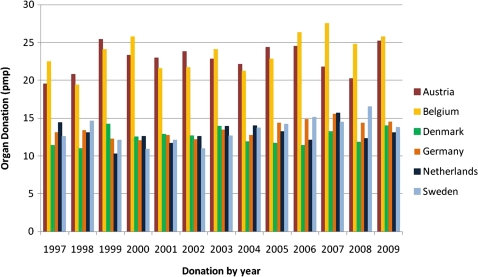

Bird and Harris modelled situations with varying relative refusal rates and drew on comparisons with EU countries that already adopted presumed consent systems.19 However, presumed consent for organ donation has been implemented with varying effect in the EU. Adoption and successful implementation of laws in one country should not be taken as a guarantee of similar success in another. Hence, though Sweden applies presumed consent, its donation rate in 2009, at 13.8 deceased donors per million population (Scandiatransplant, personal communication, 2011), was comparable with that of Germany (14.5 deceased donors per million population) and Denmark (14.0 deceased donors per million population);5 both of which require informed consent (figure 2). The figures available for Ireland, where informed consent is needed, were 21.2 deceased donors per million population in 2009.4 The nation with the highest donor rate (34.4 deceased donors per million population in 2009),20 and one often cited as evidence of successful implementation of presumed consent legislation,21 is Spain, which operates a ‘soft’ form of presumed consent where next of kin can object to organ donation.20 21 Yet, the impact of the legislation has been questioned and the high rate of donor activity attributed to the ‘Spanish Model’20 21 that demands an integrated approach with dedicated transplant coordinators, mainly intensive care physicians, involved in procurement.21 This highly coordinated network and the respect for autonomy given to the individual and their relatives is credited with improving donation rates of 14.3 deceased donors per million population in 1989 to rates of 33–35 deceased donors per million population in recent years.20 21 The majority of donations in Spain are from heart-beating donors in intensive care; live organ donation and that from non-heart beating donors are relatively low.21 The converse is true in the UK, and estimates suggest that even if a theoretical upper limit were reached, with present facilities and practices, heart-beating donor numbers in the UK would reach only half of those in Spain.21 Given that Spain introduced presumed consent in 1979,3 it is clear that a legislative change alone was not sufficient to improve donation rates. It is notable that Spain achieves a significantly higher rate of donation than does Austria,5 which relies upon a ‘hard’ approach in which views of relatives are not routinely sought.

Figure 2.

Organ-donor rates in selected EU countries 1997–2009 (Scandiatransplant, personal communication, 2011).5 pmp, per million population.

Comparisons across the EU further indicate that while a country may have relatively low overall donation rates, for certain organs the trend may be reversed. Sweden lags behind countries such as Austria, Belgium, Germany and The Netherlands with regard to overall deceased donations but has had the highest kidney-donation rate for the majority of the past 13 years (Scandiatransplant, personal communication, 2011).5

Conclusions

Data from the four UK regions show that organ donation rates vary over the last two decades and that for two of the organs, kidney and cornea, the significance of regional variations is moderated by variations in time. The cornea, in particular, shows shortfalls in donation rates from Northern Ireland. Further exploration of underlying regional differences and temporal variations in organ donation, as well as organisational issues, practices and attitudes that may affect organ donation, needs to be undertaken before considering legislation to admit presumed consent. Comparison of EU nations, and particularly Spain, indicates that improvement of organ-donation rates is unlikely to be achieved by introducing new legislation alone.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable comments of reviewers Professors D Collett and G Atkinson which have served to improve the statistical analysis of the paper.

Footnotes

To cite: Donal McGlade, Gordon Rae, Carol McClenahan, et al. Regional and temporal variations in organ donation across the UK (secondary analyses of databases). BMJ Open 2011;2:e000055. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000055

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: DM contributed to acquisition and interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision of the article and approval of the final version; CM contributed to the design of the study and the interpretation of data, critical revision of the article and approval of the final version; GR contributed to the design of the study, undertook a major part of data analysis and interpretation, contributed to drafting and critical revision of the article and approval of the final version; BP conceived the study and contributed to its design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and critical review of the article, and approval of the final version.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Smith M, Murphy P. A historic opportunity to improve organ donation rates in the UK. Br J Anaesth 2008;100:735–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHSBT. 2011. http://www.uktransplant.org.uk/ukt/newsroom/news_releases/article.jsp?releaseid=271 (accessed 8 Jul 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gäbel H. Organ donor registers. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2006;11:187–93 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organ Procurement Service Annual Report 2008–2009. Dublin: Organ Procurement Service, 2008–2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen B, Persijn G. Annual Report 1997–2009. Leiden: Eurotransplant International Foundation, 1997–2009 [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS Blood & Transplant Transplant Activity in the UK: Activity Report 2009/10. Bristol: NHS Blood & Transplant, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent B, Owens RG. Conflicting attitudes to corneal and organ donation: a study of nurses' attitudes to organ donation. Int J Nurs Stud 1995;32:484–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayward C, Madill A. The meanings of organ donation: Muslims of Pakistani origin and white English nationals living in North England. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:389–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawlor M, Kerridge I, Ankeny R, et al. Specific unwillingness to donate eyes: the impact of disfigurement, knowledge and procurement on corneal donation. Am J Transplant 2010;10:657–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Cremation Society of Great Britain Table of Cremations Carried Out in the United Kingdom, 2008. http://www.srgw.demon.co.uk/cremsoc/ (accessed 27 Oct 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delbosc B. Difficult cornea procurement: causes and consequences of the exceptional situation in France. J Fr Ophtalmol 2000;23:196–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mack RJ, Mason P, Mathers WD. Obstacles to donor eye procurement and solutions at the University of Iowa. Cornea 1995;14:249–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Howard RJ. Organ donation decision: comparison of donor and nondonor families. Am J Transplant 2006;6:190–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salim A, Brown C, Inaba K, et al. Improving consent rates for organ donation: the effect of an inhouse coordinator program. J Trauma 2007;62:1411–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gore SM, Cable DJ, Holland AJ. Organ donation from intensive care units in England and Wales: two year confidential audit of deaths in intensive care. BMJ 1992;304:349–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron S, Forsythe J. How can we improve organ donation rates? Research into the identification of factors which may influence the variation. Nefrologia 2001;21:68–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.British Medical Association Medical Ethics Committee Organ Donation in the 21stCentury: Time for a Consolidated Approach. London: British Medical Association, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organ Donation Taskforce The Potential Impact of An Opt Out System for Organ Donation in the UK: An Independent Report from the Organ Donation Taskforce. London: UK Department of Health, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bird SM, Harris J. Time to move to presumed consent for organ donation. BMJ 2010;340:c2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matesanz R, Marazuela R, Domínguez-Gil B, et al. The 40 donors per million population plan: an action plan for improvement of organ donation and transplantation in Spain. Transplant Proc 2009;41:3453–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fabre J, Murphy P, Matesanz R. Presumed consent: a distraction in the quest for increasing rates of organ donation. BMJ 2010;341:c4973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.