Abstract

Objectives

Stroke is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. This study aimed to investigate secular trends in stroke across the UK.

Design

This study aimed to investigate recent trends in the epidemiology of stroke in the UK. The study was a time-trend analysis from 1999 to 2008 within the UK General Practice Research Database. Outcome measures were incidence and prevalence of stroke, stroke mortality, rate of secondary cardiovascular events, and prescribing of pharmacological therapy for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Results

The study cohort included 32 151 patients with a first stroke. Stroke incidence fell by 30%, from 1.48/1000 person-years in 1999 to 1.04/1000 person-years in 2008 (p<0.001). Stroke prevalence increased by 12.5%, from 6.40/1000 in 1999 to 7.20/1000 in 2008 (p<0.001). 56-day mortality after first stroke reduced from 21% in 1999 to 12% in 2008 (p<0.0001). Prescribing of drugs to control cardiovascular risk factors increased consistently over the study period, particularly for lipid lowering agents and antihypertensive agents. In patients with atrial fibrillation, use of anticoagulants prior to first stroke did not increase with increasing stroke risk.

Conclusion

Stroke incidence in the UK has decreased and survival after stroke has improved in the past 10 years. Improved drug treatment in primary care is likely to be a major contributor to this, with better control of risk factors both before and after incident stroke. There is, however, scope for further improvement in risk factor reduction in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation.

Article summary

Article focus

Regional UK data have suggested a decline in stroke incidence, in association with increased use of preventive treatments and reduction in cardiovascular risk factors.

This is the first national study to examine recent trends in stroke incidence and mortality.

Key messages

In the UK, stroke incidence and stroke mortality fell consistently between 1999 and 2008.

This change coincided with a marked increase in primary care prescription of primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention therapies.

Despite these positive findings, there appears to be a need for better risk stratification as the data suggest underutilisation of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation at high risk of stroke and lower use of all preventive treatments in women than in men.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The General Practice Research Database (GPRD) is the largest primary care database in the world, containing the longitudinal records of over 3 million patients.

We are reliant on the quality of general practitioner coding in the GPRD dataset. There may be some coding error and misreporting of cardiovascular events and risk factors.

The GPRD contains secondary care data but this is limited to diagnoses; data on secondary care prescribing are not available.

Background

Stroke is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the UK. Around 110 000 strokes occur in England each year,1 with recent studies reporting an incidence of between 1.36/1000/year2 and 1.62/1000/year in 2002–2004.3 A study in the Scottish Borders reported a higher crude incidence rate of 2.8/1000/year, which was attributed to the higher proportion of elderly subjects in the population.4 Although deaths from stroke have fallen in the UK over the past 40 years,5–7 stroke accounted for around 46 500 deaths in England and Wales in 2008 (9% of all deaths).8

Current UK health policy places great emphasis on reducing strokes.9–11 Key to this is the need for better management of vascular risk factors, including hypertension, obesity, high cholesterol, atrial fibrillation and diabetes.6 11 In 2008, NHS Health Check (formerly called the Vascular Check Programme) was introduced to identify and manage vascular risk.12 More recently, NHS Improvement has identified atrial fibrillation in primary care as a priority area for the health service for 2010/11.13 From a public health perspective, it is important to determine whether national policies and preventive strategies are having an effect on stroke epidemiology. Perhaps the best data on trends in stroke come from the Oxfordshire region where data from two studies—the Oxford Community Stroke Project (1981–1984) and the Oxford Vascular Study (2002–2004)—were compared.3 The results suggested a decline in the incidence of stroke (p=0.0002) in association with increased use of preventive treatments and reduction in risk factors.

There has been no study looking at trends in stroke across the UK. We report an analysis of the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) used to investigate trends in the burden of stroke between 1999 and 2008.

Design

Objectives

The objectives of this study were (1) to investigate recent trends in the epidemiology of stroke in the UK, including risk factors associated with first and second strokes, and pharmacological therapies prescribed before and following a first stroke, and (2) to examine the trend in stroke fatality and the occurrence of a second stroke following survival of a first stroke.

Data source

The GPRD is a database of longitudinal patient primary care records, containing anonymised data on demographics, diagnoses, referrals, prescribing and health outcomes for patients from almost 500 general practitioner (GP) practices in the UK (over 3 million patients). The database covers approximately 6% of UK patients, and the geographical distribution is representative of the UK population.14 Validation studies have confirmed the high data quality and completeness of clinical records within the GPRD.15–17 A recent systematic literature review of studies using the GPRD reported that the median proportion of diagnoses correctly coded was 89%.17

Population

We identified patients aged 18 years and older who had a first stroke between 1999 and 2008. Stroke events were identified by a diagnosis for stroke within the patient record. The Read codes used by GPs to enter a stroke into a patient record do not necessarily specify the type of stroke, so we were not able to distinguish between ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes. The codes used are shown in the online supplementary material. Stroke codes used were those which described acute stroke events only—any codes for monitoring or stroke rehabilitation were excluded to ensure that we correctly identified the initial stroke event and did not record follow-up of the same stroke as a secondary stroke event.

We excluded patients if they had any coded cardiovascular disease event (including coronary heart disease or peripheral vascular disease) recorded prior to stroke, except patients with a record of transient ischaemic attack.

Analysis

Data were extracted using the GPRD GOLD online version and analysed using SAS V.9.02. The incidence and prevalence of stroke were calculated based on our stroke cohort and the total study population extracted from GPRD.

Co-morbidities were identified using Read codes (see online supplementary material). In addition to coded diagnosis, a blood pressure result above 160/100 mm Hg was defined as hypertension and a cholesterol level above 5 mmol/l (193 mg/dl) was defined as hypercholesterolaemia. Pharmacological therapies prescribed in the year before the first stroke were recorded. We assumed that patients were treated with a medication if they received at least two prescriptions for that medication in the year prior to first stroke.

For follow-up, patient data were available from the time of first stroke until the end of the study period or when the patient transferred out of the practice or died. Stroke events were considered fatal if patients had a death coded in their GP record within 56 days of the stroke. This timescale was used to allow for any delay between the death occurring and the GP receiving notification of the death and entering it into their coding system.

Second cardiovascular disease events were defined as a second stroke or other cardiovascular disease event (coronary heart disease or peripheral vascular disease event) occurring more than 56 days after a first stroke. A life table survival analysis was carried out, with an event defined as either a second cardiovascular event or death. Patients were censored if they transferred out of the practice or reached the end of the study period.

We examined trends in the proportion of patients treated with different classes of pharmacological agents in the year before and after first stroke between 1999 and 2008. For patients with GP-coded atrial fibrillation (AF) prior to first stroke, we calculated CHADS2 scores9 and recorded use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs for patients by CHADS2 score in the year prior to and after first stroke.

Results

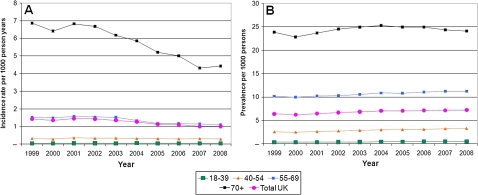

Between 1999 and 2008, first strokes were recorded in 32 151 patients with no previous recorded cardiovascular event. Over this period, stroke incidence fell by 30%, from 1.48/1000 person-years in 1999 to 1.04/1000 person-years in 2008 (p<0.001). In patients aged 80 years and over (the group at highest risk), incidence fell by 42% from 18.97 to 10.97/1000 person-years (p<0.001). Prevalence of stroke increased by 12.5% over the same period from 6.4/1000 persons to 7.2/1000 persons (p<0.001) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Incidence (A) and prevalence (B) of stroke in the UK adult population by age group.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the cohort. The average age at first stroke was 77 years in women and 71 years in men. The most commonly coded stroke risk factor was hypertension, recorded in 65% of patients. In addition, 12% of patients were coded as diabetic, and 11% had coded AF.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the General Practice Research Database stroke cohort

| Male (n=14 359) |

Female (n=17 792) |

Total (n=32 151) |

|||||||

| n | % | 99% CI | n | % | 99% CI | n | % | 99% CI | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) age | 71.06 (12.7) | (70.8 to 71.3) | 77.02 (13.0) | (76.8 to 77.3) | 74.4 (13.2) | (74.2 to 74.6) | |||

| Mean (SD) BMI (n=23 856) | 26.52 (4.6) | (26.4 to 26.6) | 26.16 (5.6) | (26.1 to 26.3) | 26.3 (5.13) | (26.2 to 26.4) | |||

| Risk factors prior to initial stroke | |||||||||

| Hypertension (GP diagnosed or >160/100 mm Hg) | 8851 | 61.6 | (60.6 to 62.7) | 12 108 | 68.1 | (67.2 to 69.0) | 20 959 | 65.2 | (64.5 to 65.9) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia (GP diagnosed or cholesterol >5 mmol/l (193 mg/dl)) | 5730 | 39.9 | (38.9 to 41.0) | 6710 | 37.7 | (36.8 to 38.7) | 12 440 | 38.7 | (38.0 to 39.4) |

| GP-coded diabetes mellitus | 1875 | 13.1 | (12.3 to 13.8) | 1909 | 10.7 | (10.1 to 11.3) | 3784 | 11.8 | (11.3 to 12.2) |

| Smoking (ever) | 8015 | 55.8 | (54.7 to 56.9) | 6210 | 34.9 | (34.0 to 35.8) | 14 225 | 44.2 | (43.5 to 45.0) |

| GP-coded atrial fibrillation | 1411 | 9.8 | (9.2 to 10.5) | 2072 | 11.6 | (11.0 to 12.3) | 3483 | 10.8 | (10.4 to 11.3) |

| GP-coded transient ischaemic attack | 897 | 6.2 | (5.7 to 6.8) | 1111 | 6.2 | (5.8 to 6.7) | 2008 | 6.2 | (5.9 to 6.6) |

| Treatments in year prior to initial stroke (at least 2 prescriptions) | |||||||||

| Antihypertensives | 6453 | 44.9 | (43.9 to 46.0) | 9649 | 54.2 | (53.3 to 55.2) | 16 102 | 50.1 | (49.4 to 50.8) |

| ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor antagonists | 3226 | 22.5 | (21.6 to 23.4) | 3845 | 21.6 | (20.8 to 22.4) | 7071 | 22 | (21.4 to 22.6) |

| β-Blockers | 2252 | 15.7 | (14.9 to 16.5) | 3581 | 20.1 | (19.4 to 20.9) | 5833 | 18.1 | (17.6 to 18.7) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2349 | 16.4 | (15.6 to 17.2) | 2988 | 16.8 | (16.1 to 17.5) | 5337 | 16.6 | (16.1 to 17.1) |

| Diuretics | 3362 | 23.4 | (22.5 to 24.3) | 6142 | 34.5 | (33.6 to 35.4) | 9504 | 29.6 | (28.9 to 30.2) |

| Anticoagulants | 703 | 4.9 | (4.4 to 5.4) | 787 | 4.4 | (4.0 to 4.8) | 1490 | 4.6 | (4.3 to 4.9) |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 4029 | 28.1 | (27.1 to 29.0) | 5471 | 30.7 | (29.9 to 31.6) | 9500 | 29.5 | (28.9 to 30.2) |

| Lipid regulating drugs | 2004 | 14 | (13.2 to 14.7) | 2221 | 12.5 | (11.8 to 13.1) | 4225 | 13.1 | (12.7 to 13.6) |

| Diabetes treatment | |||||||||

| Oral antidiabetic agents | 1193 | 8.3 | (7.7 to 8.9) | 1180 | 6.6 | (6.2 to 7.1) | 2373 | 7.4 | (7.0 to 7.8) |

| Insulin | 340 | 2.4 | (2.0 to 2.7) | 417 | 2.3 | (2.1 to 2.6) | 757 | 2.4 | (2.1 to 2.6) |

BMI, body mass index; GP, general practitioner.

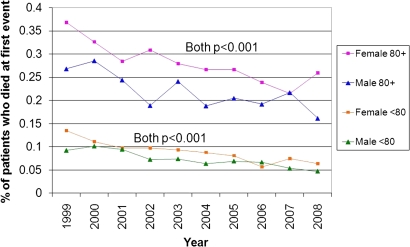

Fifteen per cent (4926/32 151) of first strokes were fatal (death coded within 56 days). Mortality was 18.6% (3301 of 17 792) in women and 11.3% (1625 of 14 359) in men. Age-adjusted to the 2008 UK population,10 the mortality difference was smaller but remained higher in women (6.8%) than men (5.5%) (p<0.001 for difference between genders). Crude mortality after incident stroke decreased from 21% in 1999 to 12% in 2008 (p<0.0001). This trend was seen in both men and women (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Stroke mortality within 56 days of first stroke by age group.

Five-year survival was 82% (11 774/14 359) in men and 81% (14 411/17 792) in women. Life table survival analysis showed that survival free of a second cardiovascular event (recurrent stroke or first CHD event) at 5 years was 74% (23 766/32 151) and similar in men and women. After first stroke, patients were at high risk of a recurrent event. Of patients followed up for 5 years, 24% (3316 of 13 599) had a second cardiovascular event; 75% of second events (2475) were strokes and 16% of these (385) were fatal within 56 days.

Stroke risk factors and management

Sixty-five per cent of patients (n=20 959) had hypertension. Of these, 67% were treated with antihypertensives in the year prior to stroke (69% of female and 64% of male patients).

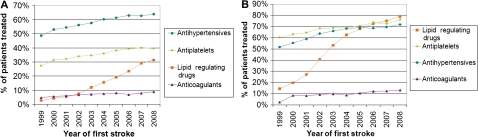

Prescription of treatment for cardiovascular risk reduction in the year prior to a first stroke increased over time (figure 3A). A similar trend was seen in prescriptions after the first stroke (figure 3B). By 2008, 96.6% of women and 97.4% of men with coded hypertension in the year after stroke were receiving antihypertensive therapy.

Figure 3.

Pharmaceutical therapies prior to first stroke (A) and in the year following first stroke (B).

Before first stroke, 38.7% of patients (n=12 440) had hypercholesterolaemia; 8.7% were treated with lipid lowering drugs in 1999, rising to 37.6% in 2008. Prescriptions for lipid lowering drugs after a first stroke also increased rapidly over the last 10 years (figure 3).

Eleven per cent of patients (n=3483) had coded AF before their first stroke: 10% of male patients and 12% of female patients (table 1). These patients were older than the general stroke cohort. The average age in the AF group at the time of first stroke was 82 years for women and 77 years for men. Stroke mortality was higher in patients with coded AF than for the overall cohort: 27% of women and 19% of men with AF died within 56 days of their first stroke. For those over the age of 70 years, 56-day mortality after first stroke was 32% in men with coded AF compared with 23% in men without coded AF (p<0.001), and 36% in women with coded AF compared with 28% in women without coded AF (p<0.001).

Women were at higher risk, with 59% having a CHADS2 score of 2 or above prior to first stroke compared with 42% of men. When we excluded age from the CHADS2 calculation, women still scored higher than men: 67% of women and 59% of men had a score of 1 or above, and 18% of women and 16% of men had a score of 2 or above.

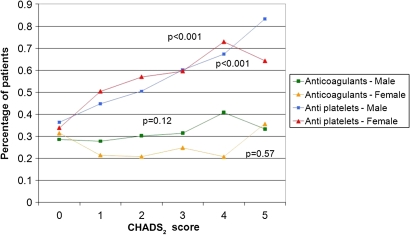

Of patients with coded AF, 25% (876) were prescribed anticoagulants before their stroke (22% of women and 29% of men). Anticoagulant prescribing did not increase with increasing CHADS2 score prior to stroke (figure 4). Antiplatelet therapy was prescribed to 52% of patients with coded AF (1796/3483) (54% of women and 47% of men) and prescribing increased steeply with increasing CHADS2 score.

Figure 4.

Percentage of GP-coded AF patients treated with anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy prior to stroke by CHADS2 score. AF, atrial fibrillation; GP, general practitioner.

For patients with coded AF at the time of first stroke, anticoagulant prescribing increased from 22% prior to stroke to 35% after stroke for women, and from 29% to 48% for men (table 2). In patients aged 80 and older, anticoagulant prescribing increased from 18% to 23% in women and from 24% to 34% in men.

Table 2.

Patients with GP-coded atrial fibrillation prior to first stroke

| GP-coded atrial fibrillation | Male |

Female |

Total |

||||||

| n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | |

| Number of patients (% of cohort) | 1411 | 9.8 | 2072 | 11.6 | 3483 | 10.8 | |||

| Baseline characteristics | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) age | 77.3 (9.8) | (76.8 to 77.8) | 82.4 (8.7) | (82.0 to 82.8) | 80.3 (9.5) | (80.0 to 80.6) | |||

| CHADS2 score prior to initial stroke (% of AF patients) | |||||||||

| 0 | 217 | 15.4 | (13.5 to 17.3) | 127 | 6.1 | (5.1 to 7.2) | 344 | 9.9 | (8.9 to 10.9) |

| 1 | 601 | 42.6 | (40.0 to 45.2) | 730 | 35.2 | (33.2 to 37.3) | 1331 | 38.2 | (36.6 to 39.8) |

| 2 | 430 | 30.5 | (28.1 to 32.9) | 877 | 42.3 | (40.2 to 44.5) | 1307 | 37.5 | (35.9 to 39.1) |

| 3 | 108 | 7.7 | (6.3 to 9.0) | 213 | 10.3 | (9.0 to 11.6) | 321 | 9.2 | (8.3 to 10.2) |

| 4 | 49 | 3.5 | (2.5 to 4.4) | 111 | 5.4 | (4.4 to 6.3) | 160 | 4.6 | (3.9 to 5.3) |

| 5 | 6 | 0.4 | (0.1 to 0.8) | 14 | 0.7 | (0.3 to 1.0) | 20 | 0.6 | (0.3 to 0.8) |

| Treatments in year prior to initial stroke (at least 2 prescriptions) (% of AF patients) | |||||||||

| Anticoagulants | 415 | 29.4 | (27.0 to 31.8) | 461 | 22.2 | (20.5 to 24.0) | 876 | 25.2 | (23.7 to 26.6) |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 668 | 47.3 | (44.7 to 49.9) | 1128 | 54.4 | (52.3 to 56.6) | 1796 | 51.6 | (49.9 to 53.2) |

| Follow-up | |||||||||

| Died within 56 days of initial stroke (% of AF patients) | 264 | 18.7 | (16.7 to 20.7) | 554 | 26.7 | (24.8 to 28.6) | 818 | 23.5 | (22.1 to 24.9) |

| Survived at least 56 days following initial stroke (% of AF patients) | 1147 | 81.3 | (79.3 to 83.3) | 1518 | 73.3 | (71.4 to 75.2) | 2665 | 76.5 | (75.1 to 77.9) |

| Treatments in year following initial stroke (at least 2 prescriptions) (% of patients who survived at least 56 days) | |||||||||

| Anticoagulants | 545 | 47.5 | (44.9 to 50.1) | 529 | 34.8 | (32.8 to 36.9) | 1074 | 40.3 | (38.7 to 41.9) |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 566 | 49.3 | (46.7 to 52) | 806 | 53.1 | (50.9 to 55.2) | 1372 | 51.5 | (49.8 to 53.1) |

AF, atrial fibrillation; GP, general practitioner.

Conclusion

Summary of main findings

Our study shows that the incidence of stroke in the UK fell by 29% between 1999 and 2008. The 56-day mortality after a first stroke fell by 43% between 1999 and 2008. Primary care management of cardiovascular risk has improved, with the majority of recorded hypertension being controlled prior to stroke, and a rapid increase in prescriptions for lipid lowering drugs to patients with diagnosed hypercholesterolaemia. However, there is a clear suggestion that risk stratification is not yet optimal, particularly in relation to patients with AF.

Comparison with existing literature

A fall in stroke incidence similar to that shown in our study has previously been reported in Oxfordshire3 and south London.18 Our findings are also in line with data from some other high-income countries, with Feigin et al reporting a 42% decrease in age-adjusted stroke incidence rates over 4 decades to 2008.19

The observed reduction in stroke incidence is likely to be related to better control of vascular risk factors both prior to and following a stroke. By the end of the study period, GPs were treating cardiovascular risk factors much more aggressively than in 1999. A previous study3 reported a trend to reduced incidence of stroke in association with increased use of preventive treatments and reduction in risk factors. Our data show improvement compared with a previous analysis of GPRD data (1997–2006) in which only 75% of patients with diagnosed hypertension were receiving antihypertensive therapy 90 days after incident stroke.20 In our study, 97% of patients with hypertension after stroke were receiving antihypertensive therapy.

Improved primary care management of risk factors presumably reflects national initiatives to reduce cardiovascular disease. These include the Quality and Outcomes Framework whereby GPs in England are incentivised to improve intervention on cardiovascular risk factors. The increased level of prescribing seen in our study is in line with a national increase in the use of statins21 and improved treatment of hypertension.22

AF is an important risk factor for stroke, but recent reports have highlighted that it is both under-recognised and under-treated.21 23 Our study confirms that such individuals have a higher mortality risk after first stroke than patients in sinus rhythm.

The CHADS2 scoring system24 is commonly used to assess stroke risk in patients with AF and help guide thromboprophylaxis. In our study, anticoagulant prescribing before stroke in patients with AF increased only slightly between 1999 and 2008. Use of anticoagulants appeared to be unrelated to the patient's CHADS2 score, as has been reported previously.25 There was a relatively high, and possibly inappropriate, level of anticoagulant prescribing in lower risk patients (those with a CHADS2 score of 0) and no increase in the use of anticoagulants with increasing stroke risk. The finding of high use of anticoagulants in AF patients at low risk of stroke has been reported previously in primary care in the UK.25

Contrary to data from a previous study using GPRD,25 we found that antiplatelet prescribing increased significantly with increasing CHADS2 score, indicating that GPs might be responding to increasing thromboembolic risk by prescribing an antiplatelet agent rather than an anticoagulant. Use of anticoagulants was lower in women than men despite women's higher CHADS2 scores. Women were older than men in the AF patient population and lower use of anticoagulants might reflect prescriber concerns that anticoagulants are more dangerous in the elderly. However, it has been shown that there is no significant difference in bleeding risk between warfarin and aspirin in patients aged over 75 years.26 The lower use of anticoagulants in women might also reflect findings from other areas of cardiovascular disease that women are treated less aggressively with drug therapy than men.27 28

Limitations of the study

We are reliant on the quality of GP coding in the GPRD dataset. There may be some coding error and misreporting of cardiovascular events and risk factors. The GPRD has quality criteria for practices involved in the data collection and we used data only from such ‘up-to-standard’ practices. A recent systematic review of the validity of diagnostic coding within GPRD reported high positive predictive values (>80%) for events such as myocardial infarction or stroke, but a lower value for AF (64.4%).16

Despite an observed difference in risk factors between men and women in our cohort, we are not able to evaluate gender difference in the risk of secondary stroke, due to the potential confounding factor of age; female patients were older than male patients. As the objectives of this study were purely descriptive, we did not make any adjustments for confounding factors. Further studies are needed to examine gender differences in stroke risk and prevention.

Implications for clinical practice

This is the first UK-wide study to investigate recent trends in stroke and it shows an encouraging reduction in the incidence of first stroke and improving survival. This is likely to be due (at least partially) to much better identification of vascular risk and the prescription of preventive therapies prior to, and after, stroke. Despite these positive findings, there are some areas where management appears to remain suboptimal. Women are less well treated than men, perhaps due to an age bias. Patients with AF, who do particularly poorly after stroke, do not appear to be appropriately risk stratified for anticoagulation therapy. Improved detection of AF and thromboprophylaxis in such patients should be a priority for healthcare systems.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Lee S, Shafe ACE, Cowie MR. UK stroke incidence, mortality and cardiovascular risk management 1999–2008: time-trend analysis from the General Practice Research Database. BMJ Open 2011;2:e000269. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000269

Funding: The study was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd.

Competing interests: MRC provides consultancy advice to a number of pharmaceutical companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, including a consultancy contract to advise the Boehringer Ingelheim epidemiology team on CV analyses. SL and AS are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd, who market a number of cardiovascular therapies and might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; SL and AS received no support from any other organisation for the submitted work.

Ethics approval: The protocol for the study has been approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee at the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

Contributors: AS and SL performed the data extraction and data analyses, and helped write the manuscript. MC advised regarding the study design and data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. He is the guarantor for the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.National Audit Office Progress in Improving Stroke Care. 2004. http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/0910/stroke.aspx (accessed Aug 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hippisley-Cox J, Pringle M, Ryan R. Stroke: Prevalence, Incidence and Care in General Practices 2002 to 2004. Final Report to the National Stroke Audit Team. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Giles MF, et al. Change in stroke incidence, mortality, case-fatality, severity, and risk factors in Oxfordshire, UK from 1981 to 2004 (Oxford Vascular Study). Lancet 2004;363:1925–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Syme PD, Byrne AW, Chen R, et al. Community-based stroke incidence in a Scottish population. The Scottish Borders Stroke Study. Stroke 2005;36:1837–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Leon DA, et al. Secular trends in mortality by stroke subtype in the 20th century: a retrospective analysis. Lancet 2002;370:1818–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Audit Office Reducing Brain Damage: Faster Access to Better Stroke Care. 2005. http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/0506/reducing_brain_damage.aspx (accessed Aug 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashton C, Bajekal M, Raine R. Quantifying the contribution of leading causes of death to mortality decline among older people in England, 1991–2005. Health Stat Quart 2010;45:100–27 http://www.statistics.gov.uk/hsq/hsqissue (accessed Jul 2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Office for National Statistics Mortality Statistics: Deaths Registered in 2008. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_health/DR2008/DR_08.pdf (accessed Jul 2010).

- 9.Department of Health Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation. London: Stationery Office, 1999. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4118614 (accessed Jul 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health National Service Framework for Older People. London: Department of Health, 2001. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4003066 (accessed Jul 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health National Stroke Strategy. London: Department of Health, 2007. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_081062 (accessed Jul 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health Putting Prevention First. Vascular Checks: Risk Assessment and Management. London: Department of Health, 2008. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_083822 (accessed Jul 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHS Improvement—Heart http://www.improvement.nhs.uk/heart/ (accessed Jul 2010).

- 14.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Gutthann SP. Use of the UK General Practice Research Database for pharmacoepidemiology. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998;45:419–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jick SS, Kaye JA, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, et al. Validity of the general practice research database. Pharmacotherapy 2003;23:686–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:128–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrett E, Thomas SL, Schoonen WM, et al. Validation and validity of diagnoses in the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010;69:4–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heuschmann PU, Grieve AP, Toschke AM, et al. Ethnic group disparities in 10-year rends in stroke incidence and vascular risk factors. The South London Stroke Register (SLSR). Stroke 2008;39:2204–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:355–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toschke AM, Wolfe CD, Heuschmann PU, et al. Antihypertensive treatment after stroke and all-cause mortality—an analysis of the General Practitioner Research Database (GPRD). Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;28:105–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health Building on Excellence, Maintaining Progress. Coronary Heart Disease National Service Framework Progress Report for 2008. http://www.cardiomyopathy.org/assets/files/Progress%20report%202008.pdf (accessed Aug 2011).

- 22.Falaschetti E, Chaudhury M, Mindell J, et al. Continued improvement in hypertension management in England: results from the Health Survey for England 2006. Hypertension 2009;53:480–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Atrial Fibrillation: the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Clinical Guideline 36. Costing report. 2006. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG36 (accessed Jul 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001;285:2864–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallagher AM, Rietbrock S, Plumb J, et al. Initiation and persistence of warfarin or aspirin in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation in general practice: do the appropriate patients receive stroke prophylaxis? J Thromb Haemost 2008;6:1500–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mant J, Hobbs FDR, Fletcher K, et al. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham atrial fibrillation treatment of the aged study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;370:493–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hippisley-Cox J, Pringle M, Crown N, et al. Sex inequalities in ischaemic heart disease in general practice: cross sectional survey. BMJ 2001;322:832–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicol ED, Fittall B, Roughton M, et al. NHS heart failure survey: a survey of acute heart failure admissions in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Heart 2008;94:172–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.