Abstract

Health care systems are faced with the challenge of resource scarcity and have insufficient resources to respond to all health problems and target groups simultaneously. Hence, priority setting is an inevitable aspect of every health system. However, priority setting is complex and difficult because the process is frequently influenced by political, institutional and managerial factors that are not considered by conventional priority-setting tools. In a five-year EU-supported project, which started in 2006, ways of strengthening fairness and accountability in priority setting in district health management were studied. This review is based on a PhD thesis that aimed to analyse health care organisation and management systems, and explore the potential and challenges of implementing Accountability for Reasonableness (A4R) approach to priority setting in Tanzania. A qualitative case study in Mbarali district formed the basis of exploring the sociopolitical and institutional contexts within which health care decision making takes place. The study also explores how the A4R intervention was shaped, enabled and constrained by the contexts. Key informant interviews were conducted. Relevant documents were also gathered and group priority-setting processes in the district were observed. The study revealed that, despite the obvious national rhetoric on decentralisation, actual practice in the district involved little community participation. The assumption that devolution to local government promotes transparency, accountability and community participation, is far from reality. The study also found that while the A4R approach was perceived to be helpful in strengthening transparency, accountability and stakeholder engagement, integrating the innovation into the district health system was challenging. This study underscores the idea that greater involvement and accountability among local actors may increase the legitimacy and fairness of priority-setting decisions. A broader and more detailed analysis of health system elements, and socio-cultural context is imperative in fostering sustainability. Additionally, the study stresses the need to deal with power asymmetries among various actors in priority-setting contexts.

Keywords: decentralisation, priority setting, accountability for reasonableness, health systems, Tanzania

Health care systems are faced with the challenge of resource scarcity and have insufficient resources to respond to all health problems and target groups simultaneously. Health care competes for resources, along with other services, such as education, water, food, just to mention a few. Hence, priority setting is an inevitable aspect of every health system (1). Priority setting, sometimes called rationing or resource allocation, has been defined as the distribution of resources (e.g. money, clinicians’ time, beds, drugs) among competing interests such as institutions, programmes, people/patients, services and diseases (2, 3) and is arguably one of the most important health policy issues of our time (4–6). Loughlin (7) defined priority setting as the process by which decisions are made as to how to allocate health service resources ethically. In this study, priority setting is defined as a process of formulating systematic rules to decide on the distribution of limited health care resources among competing programmes or patients.

The challenge of priority setting is relevant in both developing and developed countries. Developed countries’ challenges are mainly caused by ageing populations, expensive medical equipment and increasing public demand (8). However, developing countries’ challenges are due to many factors, such as the growing gap between basic health needs and available resources to satisfy them, the lack of reliable information, few systematic and formal processes for decision making, multiple obstacles to implementation such as inadequately developed social sectors, weak institutions and marked social inequalities (9, 10, 6).

A number of approaches to priority setting that are grounded in many disciplines have been suggested to support actual priority setting. Each approach presents an alternative idea of what a good and successful priority-setting process should consider (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Discipline-specific approaches to priority setting and their key values

| Discipline | Key values |

|---|---|

| Evidence-based medicine | Effectiveness |

| Health economics | Efficiency and equity |

| Philosophical approaches | Justice |

| Political science approaches | Democracy |

| Legal approaches | Reasonableness |

While approaches described above are relevant to priority setting, none of the approaches provide a comprehensive vision of priority setting. Priority setting is complex and difficult because the process is frequently influenced by political, institutional and managerial factors that are not considered by priority setting tools, such as burden of disease, cost-effectiveness or Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYS). At its core, priority setting involves choices among the full range of competing values. Values often conflict and people disagree about which values to include and how to balance them (11). Daniels (12) identified four key problems that face decision makers in the context of scarce resources:

The fairness/best outcome problem: should one give all people a fair chance at some benefit, or should one favour producing the best outcome with limited resources?

The priorities problem: how much priority should one give to the most vulnerable or worst-off individuals or groups?

The aggregation problem: when should one allow an aggregation of modest benefits to larger numbers of people to outweigh more significant benefits to fewer people?

The democracy problem: when must we rely on a fair democratic process as the only way to determine what constitutes a fair priority-setting outcome?

It is evident that priority setting decisions often go beyond weighing options of varying efficiency, effectiveness and other factors. These decisions sometimes involve trade-offs which may lead to different outcomes for different populations. Discipline-specific approaches, which focus on a single value, are inadequate to resolve disagreements about how to decide among competing values in setting priorities.

Accountability for reasonableness: a theoretical framework for fair priority-setting process

In the absence of agreement about which values should ground priority setting decisions, there has been a shift in focus away from principles, towards the process of priority setting. Klein and Williams (6), for example, stressed the importance of getting the institutional setting for the debate right, suggesting that the right process will produce socially acceptable answers and this is the best that can be hoped for. Norman Daniels and James Sabin (13) proposed a framework for institutional decision making, which they call ‘Accountability for Reasonableness’. Central to the theory is the acceptance that people may justifiably disagree on what reasons are relevant to consider when priorities are set. To narrow the scope of controversy, A4R relies on ‘fair deliberative procedures that yield a range of acceptable answers’. The A4R framework consists of four conditions (see Table 2).

Table 2.

| Relevance | The rationales for priority-setting decisions must be based on evidence, reasons and principles that fair-minded people can agree are relevant to meeting health care needs fairly under reasonable resource constraints. |

| Publicity | Priority-setting decisions, and the grounds for making them, must be publicly accessible through various forms of active communication outreach. Transparency should open decisions and their rationales to scrutiny by all those affected by them, not just the members of the decision-making group. |

| Appeals and revision | There must be a mechanism for challenge, including the processes for revising decisions and policies in response to new evidence, individual considerations and as lessons are learnt from experience. |

| Enforcement/leadership and public regulation | Local systems and leaders must ensure that the above three conditions are met. |

In 2008, when I began my PhD studies, there had been little research on how decision-making bodies in Tanzania deliberate on and make actual priority-setting decisions in the health sector. Little attention had been paid to examining the institutional conditions within which priority-setting decisions are made, i.e. what are the formal and informal rules governing priority-setting decisions at the district level in the health sector in Tanzania? Equally important, while the Accountability for Reasonableness framework has surfaced as a guide to achieving a fair and legitimate priority-setting process, our understanding of the processes and mechanisms that determine its degree of success in the achievement of fairness and legitimacy remains largely an open question. Given the growing popularity of the Accountability for Reasonableness framework to priority setting, it is imperative that one understands what works, what does not work and why and under what circumstances. One must understand the mechanisms that trigger changes as well as the contextual factors that facilitate or constrain the implementation of the framework.

This paper seeks to contribute to an improvement in just priority setting in the health care system of Tanzania. In addition, the findings contribute at least to two more comprehensive scientific debates: firstly, they contribute to the debate about the legitimacy of decision making outcomes by not focusing on the outcomes but on the process itself. They give information about the enabling and constraining factors of legitimacy on the basis of interviews of the participants. Secondly, they challenge the Accountability for Reasonability by confronting it with a new and exceptional set of data from a non-Western country.

Context, study design and methods

The study was conducted in Mbarali District in the Mbeya region of Tanzania. Mbarali District was selected by the REACT project as it was a typical rural district in Tanzania. Like other districts in Tanzania, the structure of the health system in Mbarali District has been decentralised. At the district level, the Council Health Management Team (CHMT)1 was formed with the remit of planning and budgeting for activities needed to manage, control, coordinate and support all health services in the district on a year-to-year basis. To ensure that the district health plans are in line with the national strategies in health, in 2000 the Ministry of Health developed the National Package of Essential Health Interventions as a way of ensuring that the highest priority services are fully supported. Burden of disease, efficiency, effectiveness and equity were the main principles guiding the selection of the priority areas. Based on these principles, six broad priority areas were identified: reproductive and child health; communicable disease control; non-communicable disease control; treatment of other common disease of local priorities within the district; community health promotion and disease prevention; and management support.

Based on this national framework, all districts produce an annual Comprehensive Council Health Plan (CCHP) that incorporates all activities of the District Health Services and all sources of funding at the council level (government funds, locally generated funds, local donor funds etc.). However, it is imperative to note that the national framework does not completely deprive the districts, health facilities and the communities of the authority to set priorities, but it provides them with a framework within which to set their priorities.

The CCHP is approved by the Council Health Services Board (CHSB) that consists of community representatives, officers from other departments and representatives from the private sector. The final plan is approved at the Full Council Meeting. The Regional Secretariat (Regional Health Management Team) approves the CCHP and forwards it to national level. The Prime Minister's Office-Regional Administration and Local Government (PMO-RALG), together with the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW), assesses the CCHPs and must give its final approval before funds can be disbursed to the Local Government Authorities.

The REACT project in Tanzania

In 2006, researchers from many institutions (the Primary Health Care Institute, the Institute of Development Studies, the University of Dar es Salaam and the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania, in collaboration with research institutions from Europe) asked whether Accountability for Reasonableness, with its emphasis on openness, democratic process and deliberation, could be relevant in low-income countries with its different cultural traditions and limited resources. These researchers teamed with decision makers and launched the project called ‘Response to Accountable Priority Setting for Trust in Health Systems’ (REACT) in Mbarali District in Tanzania.

The REACT project aimed at testing the application and effects of the Accountability for Reasonableness framework. A preliminary phase of the implementation of the Accountability for Reasonableness framework in the district began in 2006, involving gathering baseline data, consultation and planning. The full application of Accountability for Reasonableness began in 2008. However, the actual implementation of the Accountability for Reasonableness intervention fell short of the initial plan. A delay in funding disbursements delayed part of the implementation process. With time, and as circumstances dictated, the plan to monitor and evaluate service domains such as malaria, HIV/AIDS, emergency obstetric care and generalised care were dropped, and the focus remained merely on monitoring the priority-setting process and management changes within the CHMT and at the district hospital.

The project applied Accountability for Reasonableness through participatory and inter-disciplinary action research design. The application of Accountability for Reasonableness includes: describing existing priority-setting practices in the district, evaluating the description using Accountability for Reasonableness and implementing improvement strategies in a continuous process to address gaps in Accountability for Reasonableness conditions (14).

To meet its goals, the REACT intervention employed three overlapping strategies: (1) active collaboration with district health decision makers, (2) sensitisation workshops with stakeholders and (3) the presence of a project focal person in the district to facilitate the implementation process.

I joined the REACT project as an associated PhD research student. I became an independent researcher during the entire period of the project implementation while maintaining a close link with the Action Research Team and other institutions participating in the implementation of the project. In addition to the baseline and project implementation data, I gathered other data relevant to my research questions. Therefore, this study partly consists of investigation of its own, with the aim of examining existing organisational and health care management systems at the district level.

The overall study design

The study adopted a qualitative case study methodology, i.e. an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context (15). The study was designed and implemented in two phases: the baseline study and the project implementation study. The first phase aimed to document the actual priority-setting practices in Mbarali district. The second phase aimed to document the experiences of implementing the A4R approach in Mbarali district, Tanzania. The data analysed in this article are an outcome of both phases of the accompanying evaluation research.

Sampling and data collection techniques

To cover a wide range of views of different cadres, the study used purposive sampling techniques to select key informants. Participants were purposefully selected by virtue of the positions they held either in the district administrative office, in the CHMT, the health facilities, or in the community (see Table 3 for a list of respondents). Interviews with key informants were carried out from October 2006 to February 2007, and between June and August 2008. Additional interviews on the implementation of the Accountability for Reasonableness intervention were conducted between January and February 2010. Walt and Gilson's 1994 framework for health policy analysis and the Accountability for Reasonableness framework were used as guides for developing interview questions. Planning meetings were observed by the REACT project focal person to get more insight into the planning and priority-setting processes. Observation of the planning meetings provided information about the actual participants and the information being used as well as the power dynamics. The documents reviewed included: the Comprehensive Council Health Planning Guidelines, the National Package of Essential Health Interventions in Tanzania, guidelines for the Establishment of Council Health Boards and Committees, districts’ annual implementation reports and minutes of the CHMT and published and unpublished articles and reports on the priority-setting process in Tanzania as well as REACT project implementation documents (reports, minutes).

Table 3.

Categories of respondents

| Number interviewed | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Designation and responsibility | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | |

| 1 | Members of CHMT | 10 | 7 |

| 2 | Local government officials | 6 | 2 |

| 3 | Members of user committees and boards | 8 | 3 |

| 4 | Member of NGOs (advocacy group) | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | Private service providers/faith-based organisations | 2 | |

| 6 | Knowledgeable community members | 3 | |

| 7 | Heads of a health facility (health centres) | 2 | |

| 8 | Health workers at the district hospital | 5 | |

| Total | 31 | 20 | |

Data were classified and organised according to key themes, concepts and emergent patterns (16). The analysis process involved a series of analytical steps. First, a code manual was developed based on the research questions. Second, the transcripts of each interview were read through and responses were identified to the main questions raised by the study. Data were coded to initial themes and were then sorted and grouped together so that they were more precise, complete and generalisable (17). As patterns of meaning emerged, similarities and differences were identified. Finally, data were summarised and synthesised retaining, as much as possible, key terms, phrases and expressions of the respondents. After this analysis, data were triangulated to allow comparison across sources and different categories of stakeholders. The careful and systematic process of analysis and reflection served to ensure analytical rigour (18).

Main findings

In what follows, findings from the baseline and A4R implementation experience study are presented. While findings are presented as discrete sections, they should not be viewed as mutually exclusive issues because there is overlap between them.

Who sets health care priorities in Tanzania?

The priority-setting process has been devolved to the district and health-facility level. Identification of priorities has to begin at the grassroots, with district-level monitoring of adherence to budget ceilings as well as to national policy requirements on core issues. Ideally, the process should result in health facilities (health centres and dispensaries) and community representatives providing input to district priority setting. However, as the priority-setting process was studied, it was observed that this was not the case. Health boards and committees had little impact on the planning and priority-setting process. Consequently, priority setting for health at the district-level depended heavily on the group dynamics within the CHMT rather than other actors.

Interviews with members of user committees and boards revealed that they had recently been established in the district and did not seem to have played a major role in determining district health priorities. As stated by one member of a user committee:

We are in the community and know many problems that occur here. Therefore our voices should be heard, but this does not happen. (interview with a member of CHSB)

Poor attendance of public meetings, lack of interest and education, lack of monetary gain, cultural barriers and suspicion were some of the reasons given for this. Furthermore, priority setting in the district often started late that made it hard to conduct meaningful participatory planning. The fact that funds were earmarked for certain purposes was viewed as a problem, as were unexpected budget cuts and irregular budgetary remittances to the district.

What influences the selection of priorities at the district level in Tanzania?

Two main factors influence priority setting at the district level. The most common influence mentioned was national-level priority, followed by district-level challenges. Ideally, planning guidelines that come from the national government require that interventions in each priority area be selected on the basis of magnitude, severity, feasibility and cost. The actual allocation of resources has to be based on budget ceilings, as specified in the National Basket Grant guidelines. However, interviews with district health managers, and analysis of field notes revealed that CHMT members use projections based on previous plans. So, the plan was based largely on what was funded the previous year, with some minor adjustments for demographic or political factors. The use of epidemiological or cost-effectiveness evidence tends to be only a small component of the decision:

…The process lacks accurate information which is useful in guiding priority setting...Information on morbidity and mortality is largely inadequate and not reliable. (interview with members of the CHMT)

The political contexts in which the CHMT operates also influence priority-setting decisions. These include both nationwide political decisions and politics at the district level. The priorities of the national government influence the priorities that the CHMT gives to particular areas of health policy. Many CHMT members indicated that, while some of their priorities came directly from the districts, in situations where district-level priorities conflict with national priorities, the national priorities take precedence:

When identifying priorities we usually have district data along with instructions from the Ministry. What we do is trying and compares [sic] problems identified at the national level with those which we at the district level have identified as priorities. National priorities which are similar to district problems are given first priority...However, even though we identify our own district priorities at the end of the day we must observe the national priorities. (interview with members of the CHMT)

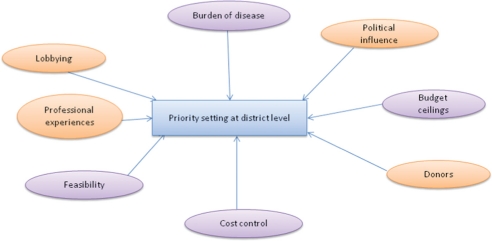

Furthermore, a minority of members of the CHMT who were interviewed pointed out that lobbying, professional experience and donors had influence in the priority-setting process. Fig. 1 illustrates various factors that influence priority-setting decisions at the district level.

Fig. 1.

Factors influencing CHMT's priority-setting decisions: Source (19).

Which institutional factors influence the district level priority-setting process?

A number of institutional and organisational factors influenced the district-level planning and priority-setting process. First, there appears to be no clear delineation of responsibilities and relationships between the levels of local government and health committees and boards. The planning guidelines were not clear in explaining how power relations should work between the various bodies created by the councils. For example, the CHSB did not have an automatic mechanism for collaboration with other bodies such as the Hospital Governing Committee. As a result, problems of mutual concern were not discussed and solved.

Second, there appeared to be limited capacity of the CHSB to oversee and scrutinise district health plans and priorities. It was indicated that members of the CHSB had received no formal training on planning, budgeting and the prioritisation process to enable them to perform their duties. In addition, for quite a long time, the CHSB had not held meetings due to limited funds. In most cases, district health plans and reports were submitted to the Full Council, without first being scrutinised by members of the CHSB, as required by the planning guidelines.

Furthermore, the district health plans were not scrutinised properly in the Full Council meetings. Although CCHPs were tabled at the Full Council meetings, local councillors appeared to approve them without an adequate understanding of their implications:

At the Full Council meetings, although all members are involved, in my experience, there are many people who do not understand the issues which are discussed there because most health issues discussed are not understood by non-medical personnel...they just vote to accept the resolution without a thorough understanding. You may find that the resolution was passed by all, but in reality it was a decision proposed by one person due to his/her influence because others don't understand health-related issues properly. (interview with a councillor)

According to some respondents, this was due to insufficient time allocation for Full Council meetings to enable councillors to read and understand all the items in the district health plans before approval. Some respondents also felt that because most of the members of the Full Council are politicians, they had insufficient knowledge of health care priority setting. Thus, although district health plans and budgets were made, supervision of, and adherence to these was not a priority. Both health workers and the general public had no mechanism to hold district health managers accountable.

Whose voice was heard in the priority-setting process and how?

A review of how the budgeting process was undertaken showed an unequal distribution of power between the various actors involved in the planning and priority-setting process. All stakeholders interviewed at district level felt themselves powerless to influence the amount of funding coming to them from the central government. It was evident that the national government had more power over the purse strings than the bottom level, despite the popular policy claim of bottom-up planning and budgeting.

Power asymmetries were manifest even between the CHMT and planning team members. Findings from interviews indicate that power asymmetries within the CHMT and the planning team were most clearly exemplified in terms of the degree of authority they exercised, and the varying amount of planning information to which they had access. There was also evidence that the managerial position of the District Medical Officer (DMO), District Planning Officer (DPLO) and the District Treasurer (DT) gave them the power to set the agenda, provide technical advice and control the priority-setting process in the district. The DMO was thought to have had the final authority in the actual decision-making process.

Power imbalances were also reflected in the differences in the granted preparation time and access to the available planning information and guidelines. Clear power differences were also revealed between district health professionals (public) and representatives from the private sector and faith-based organisations (FBOs). Access to the planning guidelines appears to have been confined to the DMO and a few CHMT members. Planning guidelines were kept in the DMOs office and were sent to the planning meetings the same day. Many members of the planning team, particularly those from the private sector and NGOs had no time to review the planning guidelines and information before the planning meetings. Consequently, participation by representatives from FBOs, NGOs and the private sector was minimal, and they expressed that their views were hardly incorporated in the final CCHP.

What were stakeholders’ perceptions of the accountability for reasonableness framework?

The picture of the relevance of the A4R framework emerging from the respondents was, overall, a positive one. First, all respondents shared the opinion that involving multiple stakeholders would ensure that a wide range of relevant values and principles were taken into account and thus would improve the fairness, transparency and legitimacy of the process. Second, all respondents recognised that transparency has the potential for enhancing the democratic process by helping members of the community learn how to allocate health care resources thoughtfully and fairly. Furthermore, most respondents shared the view that a formal appeals mechanism would provide opportunities for people to express their dissatisfaction with the decisions taken.

When asked about district health plans and budgets both before and after the Accountability for Reasonableness intervention was introduced, respondents were overwhelmingly receptive to the change. The planning and priority-setting processes were now perceived as more participatory and transparent:

I think there are very big changes. In the 2008 planning year, the CHMT sat alone in identifying district priorities. After the start of the REACT project, it was deemed necessary to widen the scope and involve many more stakeholders in the process of preparing the district health plan. Last year 2009, we sent letters to health facilities requesting their committees to prepare their priorities and submit to the CHMT. (interview with a member of CHMT)

With regards to publicity, it was evident that district health priorities had become readily accessible to the members of the CHMT and hospital workers. The district priorities were communicated to programme leaders and other hospital staff through the staff meetings. Priorities were also translated into Kiswahili (the national language) and were pinned on the notice board at the district hospital, health facilities and ward offices:

I would say there are significant changes. Starting from 2009 we have seen hospital priorities displayed on notice boards and in offices. In the past, even the content of the district health plan was not usually known. You would just be told that there was going to be a seminar or training but you would never know what the plans were and whether they were implemented or not. (interview with health worker)

When they were finally asked about changes in power asymmetries within the CHMT, respondents were also receptive to the change dynamics. A vast majority of CHMT members believed that their involvement in planning and priority setting had increased over the past 2 years. The CHMT members reported that they were now able to appeal against DMO decisions:

As days pass by there are gradual changes. In the past very few people dominated the meetings. But currently there is room for other members to air their opinions. (interview with a member of CHMT)

The REACT project has opened our eyes. We have now gained confidence and we are able to argue firmly in front of the chairperson. (interview with a CHMT member)

It was observed in the 2009/2010 planning and budgeting process that members were given the chance to raise issues and engage in discussion, although the chairperson appeared to continue to dominate the discussion and have influence on the final outcome. All this amounts to an increased awareness of the need to prioritise explicitly in view of the many demands on limited resources.

How was the A4R intervention shaped, enabled and constrained by contextual factors?

A number of factors positively or negatively influenced the implementation of the A4R conditions in the planning and management of district health services. The presence of participatory structures under the decentralisation framework appeared to be the main factor that facilitated the adoption and implementation of the A4R intervention in the district. The decentralisation process meant that there was already a commitment from top politicians to devolve power, authority and accountability to the districts. Whilst national health policy documents were important, in most cases local contextual factors also appeared to facilitate the implementation process. It was evident that the desire of the CHMT to engage different stakeholders, and listen to their views and expectations of the priority-setting process, influenced the application of the A4R conditions. The CHMT members invested a considerable amount of effort and resources in identifying the relevant internal and external stakeholders, and to involve them in the planning and priority-setting process. Before the start of the A4R intervention in the district, pre-planning meetings for developing district health plans involved only seven core CHMT members, but this number was increased to about 18, including a coordinating person from NGOs, the District Planning Officer (DPLO) and the Community Development Officer. Most recently, representatives from groups representing women, youth, the elderly and the disabled began to attend the annual priority-setting meeting.

Additionally, the importance of having a project focal person and the Action Research Team dedicated to the development and implementation of a fair and explicit approach to priority setting became evident in the district. The collaborative efforts between researchers and district health managers were seen by many CHMT members as the way to build the people's confidence that this project really was about benefiting the district. The fact that the Primary Health Care Institute (PHCI) had established a long-working relationship with the study district facilitated the adoption and implementation of the intervention. Furthermore, frequent meetings between the researchers and district health decision makers seemed to have increased the level of trust, and facilitated receptivity to the adoption and implementation of the Accountability for Reasonableness innovation.

However, while some significant progress was made to involve multiple stakeholders and disseminate priorities to health workers and the public, a number of contextual factors appeared to constrain the full implementation of the A4R approach. First, the existing structures at the grassroots level (such as village council meetings, village general assemblies and health facility governing committees) that could be used to steer stakeholder engagement were not functioning well due to lack of incentives and low level of awareness of their roles and responsibilities.

The CHMT's efforts to implement the A4R approach to priority setting were also stymied by the delay in the disbursement of funds by the central government. Furthermore, the CHMT members felt that interference from higher authorities hindered efforts to implement a fair and transparent priority-setting approach. One respondent remarked:

Many responsibilities and instructions from higher administrative levels also affect our desire to implement a transparent and fair priority-setting process. Sometimes things are brought to you and you are told that it must be included in the plan and if it is not there the plan wouldn't be accepted at higher levels. (interview with a member of the CHMT)

Planning guidelines imposed by the national government were also frequently mentioned by CHMT members as barriers to stakeholder involvement in the planning process. Many CHMT members felt that there were too many constraints tied to the national basket system that prohibited the CHMT from spending above its budget allocation. They stated that the system often determined how to spend the money and how much could be spent on certain items or expenditures. For example, one CHMT member explained the constraints placed on the districts thus:

Some of the items in the guidelines hinder us from doing what we like. For instance, the guidelines prescribe the percentage of resources, which should be allocated to each priority. In effect, a lot of money is allotted to priorities that are not very critical in our district, while priorities that are of great importance to the district get insufficient funding. So, there should be flexibility, as far as resource allocation is concerned. (interview with a member of the CHMT)

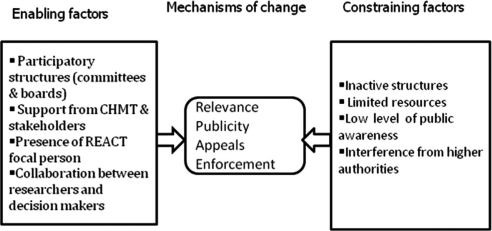

Furthermore, the low level of public awareness and lack of appeals culture were barriers to achieving explicitly fair approaches to priority setting in their context. Fig. 2 summarises the contextual factors that facilitated and/or constrained the implementation of Accountability for Reasonableness.

Fig. 2.

Contextual factors that facilitated and constrained the change process.

Discussion

This study revealed that, despite the indisputable national rhetoric on decentralisation, practice in the district involved little community participation. Official government documents clearly state that the planning and priority-setting process in the context of decentralisation would be done in line with the principles of public participation, democracy, transparency and accountability at all levels from the national level to the community level. Emphasis is placed on devolving power and resources to the community level and, in particular, on the role of the health care committees and boards. It is evident that decentralisation does not automatically provide adequate space for community engagement.

In the first place, the content of the annual district health plans seemed to be largely dictated by national priorities, despite the emphasis on decentralisation of decision making and budgeting. Secondly, the high level of conditionality associated with local government funding gave the CHMT little room to alter funding allocations, especially in the recurrent budgets. However, national guidelines could be an important tool for effective decentralisation. Given the weakness of accountability mechanisms at the district and grassroots levels, guidance is needed on the criteria to be debated in the priority setting and resource-allocation processes. Decentralisation may become problematic if local decision making on how to use resources is made without guidance on citizen rights and local-level responsibilities. Nevertheless, it is important that such guidance does not impose new outside criteria, but both operationalises and balances established planning criteria.

In addition, grassroots participation appears to have little impact on the planning and priority-setting processes. District health plans are the products of a few members of the CHMT, with community bodies and private partners operating at best as a rubber stamp to approve the decisions taken. User committees, boards and the public seemed unable to affect quality of the decentralised health care planning and priority-setting processes. One could argue that decentralisation has both ‘supply’ and ‘demand’ sides. Demand for accountability by citizens requires education, mobilisation and democratisation at the grassroots.

Furthermore, this study found that A4R was perceived as an important approach for improving priority setting and health service delivery. A4R helps to operationalise the concept of fairness at the district level. Traditionally, health workers, patients and the public have been excluded from planning and priority setting. The focus on the process of priority setting, rather than priorities, is an innovation that responds to the long-standing calls for an increased focus on process and context to enhance the delivery of quality services (20).

However, while the A4R approach to priority setting was perceived to be relevant in strengthening transparency, accountability, stakeholder engagement and fairness, integrating the innovation into the current district health systems was challenging. National guidelines, budget ceilings, interference from higher authorities, unreliable and untimely disbursement of funds, inactive grassroots participatory structures, and low awareness of health staff, stakeholders and communities were the major obstacles to the implementation of the Accountability for Reasonableness intervention.

Implications of the findings to the accountability for reasonableness approach to priority setting

The results suggest that three important points should be taken into account. First, there is need for greater engagement of affected communities in relevant decision-making processes than currently exists. Although Daniels (21) acknowledged that stakeholder participation may improve deliberation about complicated matters, he believed that it is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition of Accountability for Reasonableness. While Daniels’ view, that the mere fact of public involvement in priority-setting ensures neither true representation nor a better quality of decision-making process, is persuasive, without greater opportunities for engagement of affected communities, it is uncertain how the priority-setting process can enhance legitimacy. Stakeholders affected by the decisions should have an input in determining how priorities are ranked.

Whereas Norman Daniels is correct that, even with stakeholder participation, a process not aimed at accountability for reasonableness will not achieve legitimacy (21), it would be important for the relevance condition aiming for inclusion of stakeholders in the mechanism for achieving compromise. There is, therefore, an urgent need to broaden the involvement of stakeholders from the demand side, making sure also that representatives of vulnerable groups are present and heard. Having a wide range of stakeholders participating in deliberation helps include the full range of relevant arguments, enhances legitimacy and facilitates the implementation of the decisions made. Furthermore, to make the most of channels of stakeholder influence, deliberate efforts to sensitise the public, health care staff, ward and village development committees and village health governing committees to the importance of priority-setting using Accountability for Reasonableness is necessary.

Second, the findings underline the need to recognise and deal with power asymmetries among various actors in the priority-setting process. More attention needs to be paid to issues of difference and the challenges of inclusion. It was evident that while priority setting was meant to be participatory, this was not the case. In practice, most of the district health plans were products of a few members of the CHMT, with private partners and community bodies at best operating as a rubber stamp for decisions taken without their input. The findings suggest that simply establishing institutional arrangements of participatory planning, priority setting and governance – in the absence of prior awareness and without the strong capacity for exercising countervailing power against persisting ‘rules of the game’ – will not result in greater responsiveness to community needs and priorities. Rather, the best-intentioned mechanisms for participatory planning and priority setting might simply be dominated by the local elite.

This study reinforces the findings of an earlier study in high-income countries that advocated the need to add the empowerment condition in the Accountability for Reasonableness framework (22). The empowerment condition requires that steps should be taken to optimise effective stakeholder participation and minimise the impact of power differences in decision making (22). In this case, empowerment of user committees and boards enables them to be pro-active, to suggest solutions to local authorities and to insist on decisions being made and implemented. One of the tools in empowering boards and committees is the provision of good information, more so if they are involved in its collection. Well-informed members of boards and committees will be in a better position to make sound and informed decisions, and to participate effectively in the implementation of priorities. Another way to empowerment could be to engage the committees and boards in identifying not only community needs but also the available local resources, and in working out acceptable solutions (23).

Third, this study suggests that attempts to establish fair priority-setting mechanisms have to recognise constraints in the local contexts of sociopolitical conditions and traditions. In this case, the A4R framework should be implemented with flexibility to allow for the local context. Since Daniels and Sabin developed A4R in the context of US private care organisations, their fourth condition focused on public or voluntary regulation that is the most obvious means of enforcement. In Mbarali district, it was evident that the enforcement mechanism needed to go beyond a voluntary or public regulation of the process, to ensure that the relevance, publicity and appeals/revisions conditions are met. While Tanzania has adopted a number of policies, rules and regulations that enforce transparency, accountability and stakeholder participation, for almost two decades little has been done at the district and grassroots levels to translate the same into practice. This thesis, therefore, re-emphasises the need to build strong and effective organisational leadership and oversight that ensures the implementation and sustainability of the A4R approach. Leadership can be described as a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal. Good leadership is about providing direction to, and gaining commitment from partners and staff, and thereby facilitating change. In building the leadership capacity of district health care leaders, there is a need to go beyond the skills of medical practitioners to the skills of teamwork, advocacy, negotiation, lobbying, data management, governance and accountability to achieve results that are fundamental in making a district health system effective. These skills could be acquired through a variety of means, including coaching, mentoring and action learning.

Furthermore, because the A4R approach emphasises inclusiveness, participatory planning and priority setting, the approach could be seen as threatening to some members. The implementation of the A4R approach thus requires strong support from oversight institutions. At present, an increasing range of oversight institutions, such as the Full Council, CHSB and Facility Governing Committees and Boards, are too weak to hold district health managers accountable. There is an urgent need to build the capacity of these institutions through training and sensitisation to enable them carry out the range of functions required for effective district health system governance, including overseeing the implementation of agreed health priorities. The capacity-building plan would, amongst other things, entail refresher courses on the roles and functions of boards and committees, management and governance, participatory planning and priority setting processes and an overview of the health services within the local authority.

Conclusion

This study aimed to analyse health care organisation and management systems in Tanzania, and explore the potential and challenges of implementing the A4R approach to priority setting. The study has revealed that, despite the indisputable national rhetoric on decentralisation, practice in the district involved ineffective and limited participation. The findings of this study demonstrate clearly that the setting up of health priority-setting structures alone is unlikely to lead to significant improvements unless accompanied by transparency and accountability mechanisms aimed at ensuring the effective use of resources. In this regard, one could rightly argue that the participatory priority-setting approach that has no stakeholder participation, and minimises the impact of power differences in the decision-making context, is less likely to bring about strong and effective health systems.

Additionally, the study has shown that the road to strengthening fairness, transparency and accountability in resource-poor settings is neither straight nor smooth. There is a need for a broader and more detailed analysis of health system elements and sociocultural contexts, and such research can help promote better prediction of the effects of the innovation and pinpoint stakeholders’ concerns, thereby illuminating areas requiring special attention and fostering sustainability. Equally important, the study encourages the intensification of social networks between decision makers and researchers to build sound working relationships that foster the adoption and integration of innovations in health care settings. Furthermore, the study suggests a need for building strong and effective organisational leadership as an important factor in the successful implementation and sustainability of the A4R approach. In building the leadership capacity of district health care leaders, there is a need to go beyond the skills of medical practitioners to promote the skills of planning, negotiation, lobbying, data management, governance and accountability to make district health systems effective.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere thanks to the Swedish Center Party Donation for Global Research Collaboration, the Swedish Research School for Global Health, the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, the African Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship offered by the African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC) in partnership with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and Ford Foundation and the EU-funded REACT project, grant number: PL 517709 for the financial support to make this study possible. I am also grateful to Anna-Karin Hurtig, Miguel San Sebastian and Peter Kamuzora for their support, advice and comments which generously helped improve my research project.

Footnotes

The CHMT consists of: the District Medical Officer (chairperson), District Nursing Officer, District Laboratory Technician, District Health Officer, District Pharmacist, District Dental Officer and District Health Secretary (secretary to the team). Other co-opted members of the CHMT may include: Reproductive and Child Health Coordinator, Tuberculosis and Leprosy Coordinator, Malaria Focal Person, Aids Coordinator and Cold Chain Operator who are invited in the CHMT meetings as the need arises.

Conflict of interest and funding

The author has not received any funding or benefits from industry to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Goold SD. Allocating health care: cost-utility analysis, informed democratic decision making, or the veil of ignorance? J Health Poli, Poli Law. 1996;21(69):98. doi: 10.1215/03616878-21-1-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson J. Ethics and priority setting for HTA: a decision-making framework. University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics: Canadian Priority Setting Research Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKneally MF, Dickens BM, Meslin EM, Singer PA. Bioethics for clinicians: 13. Resource allocation. Canad Med Assoc J. 1997;157:163–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin D. Making hard choices: the key to health system sustainability. Prac Bioethi. 2000;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ham C, Coulter A. International experience of rationing. In: Ham C, Robert G, editors. Reasonable rationing: international experience of priority setting in health care. London: Open University Press; 2003. pp. 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein R, Williams A. Setting priorities: what is holding us back-inadequate information or inadequate institutions? In: Coullter A, Ham C, editors. The global challenge of health care rationing. Philadelphia: Open University Press; 2000. pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loughlin M. Rationing, barbarity and the economist's perspective. Healt Care Analy. 1996;4:146–56. doi: 10.1007/BF02251220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norheim O. Limiting access to health care: a contractualist approach to fair rationing. Oslo: Oslo University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapiriri L, Martin DK. A strategy to improve priority setting in developing countries. Healt Care Analy. 2007;15:167–59. doi: 10.1007/s10728-006-0037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryant JH. Health priority dilemmas in developing countries. In: Coulter A, Ham C, editors. The global challenge of health care rationing. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2000. pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein R. Dimensions of rationing: who should do what? British Med J. 1993;307:309–311. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6899.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniels N. Four unsolved rationing problems: a challenge. Hastings Cent Rep. 1994;24:27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniels N, Sabin J. Setting limits fairly: can we learn to share medical resources? New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byskov J, Bloch P, Blystad A, Hurtig AK, Fylkesnes K, Kamuzora P, et al. Accountable priority setting for trust in health systems-the need for research into a new approach for strengthening sustainable health action in developing countries. Healt Res Poli Sys. 2009;7:23. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritchie J, Spencer L, O'Connor W. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, editors. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage Publications; 2003. pp. 219–62. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kvale S. Interviews, an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patton M. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maluka S, Kamuzora P, San Sebastián M, Byskov J, Ndawi B, Shayo E, et al. Decentralized health care priority setting in Tanzania: evaluating against accountability for reasonableness framework. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:751–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilson L, Mill A. Health sector reforms in sub-saharan Africa: lessons of the last 10 years. Healt Pol. 1995;32:215–43. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(95)00737-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniels N. Just Health: Meeting ealth needs fairly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson JL, Martin DK, Singer PA. Priority setting in hospitals: fairness, inclusiveness, and the problem of institutional power differences. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:2355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapiriri L, Norheim OF, Heggenhougen K. Using burden of disease information for health planning in developing countries: the experience from Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:2433–41. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]