Surgeons are instrumental in providing appropriate, cost-effective health care.1 This responsibility implies that we must try to maintain a standard of care that is consistent with the best available evidence. To pursue an evidence-based approach to surgical care, a surgeon must be able to review relevant articles from the literature in an efficient manner. Therefore, the contemporary surgeon must have a simple mechanism for carrying out a complete literature search. Other publications in this evidence-based surgery series have described how to review various articles from the surgical literature. In this paper, we provide the surgeon with guidelines for searching the literature and a template for constructing an effective search strategy.

Clinical scenario

You are a busy surgeon in a high-volume surgery practice. During your regular “OR day,” a colleague notices that you do not give heparin prophylaxis for postoperative deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in patients undergoing colorectal surgery. Your colleague suggests that a more aggressive approach to DVT prophylaxis is appropriate and encourages you to change your practice. You are concerned that heparin may increase the risk of perioperative hemorrhage. You wish to determine the most effective means of reducing the risk for postoperative DVT but are uncertain how to proceed. Therefore, you will need to carry out a literature review, which you hope to have completed before your next major case in 2 days' time.

Developing a strategy for a literature search

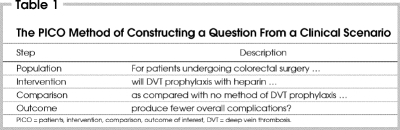

The essential component of an effective search strategy is an appropriately designed question. The question usually arises out of some uncertainty in clinical care. The question should be clear and focused — describing a patient or clinical problem, the intervention or exposure, relevant comparisons and the outcomes of interest. This is the PICO method for producing well-designed clinical questions (Table 1).2,3 It is helpful to describe the clinical problem in your own words. This method forms the basis for an effective search strategy by building an appropriately worded question, a task that is not as simple as it seems and can be a time-consuming exercise. However, an appropriately constructed question facilitates subsequent literature search.

Table 1

Underscoring the key words in the question now helps you to identify initial search terms. Use of these terms will create a search strategy based on text words. Text words are those exact words found in the study title or abstract. Selecting general or nonspecific terms will generate a long list of studies, many of which may be unrelated to your question. Conversely, more specific search terms will result in a more effective and focused search strategy. We have constructed a search strategy using text words in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1. Example algorithm for carrying out a literature search. DVT = deep vein thrombosis; PICO = problem, intervention, comparison, outcome; RCTs = randomized controlled trials.

Searching the literature

Once you have developed the clinical question, the next step is to decide which tool you should use to search the literature. Most journal articles relevant to the practising surgeon are indexed in the National Library of Medicine (NLM) MEDLINE database. MEDLINE contains bibliographic citations from over 4000 biomedical journals published in the United States and 70 other countries. It has more than 10 million citations dating from 1966 to the present. Other databases are available that may be more appropriate for specialized searches of the literature (e.g., EMBASE is a widely used biomedical and pharmaceutical database), but we will focus only on MEDLINE in this discussion.

Currently, MEDLINE may be searched most effectively “online” using a personal computer and standard Internet access. Online searching of MEDLINE through a search engine is generally easier to use and more current than print searching (i.e., Index Medicus).4 In this article we will focus on electronic or computer search strategies.

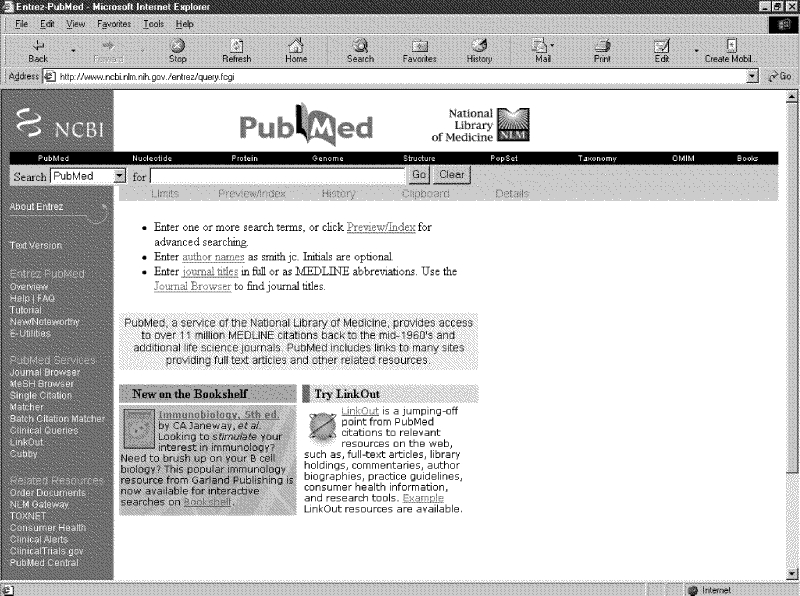

MEDLINE may be searched at no cost using the NLM Internet search engine PubMed (Fig. 2). This search engine constructs and performs complex queries or searches of a database of information (MEDLINE). Other online search engines are available. A comparison of commonly used MEDLINE services is available at www.medmatrix.org/info/medlinetable.asp. Table 2 provides information about the free “four star” search engines as rated by Medical Matrix. We suggest the reader start with PubMed, although any of the listed search engines may be used. MEDLINE may also be searched offline at any site providing access to archived MEDLINE citations that may be stored in CD-ROM format (e.g., university libraries).

FIG. 2. Home page of the PubMed search engine for searching MEDLINE. Copyright of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Md.

Table 2

One advantage of PubMed is that it searches another database at the same time: PREMEDLINE. PREMEDLINE allows you to search for the author, title and abstract of journal articles before the records have been indexed in MEDLINE. Certain journals may not be indexed for over a year after publication whereas PREMEDLINE records are updated daily. The ability to access more recent articles through this database may improve the accuracy and yield of your search. If you want to be sure to include PREMEDLINE in your search then your strategy must have text words.

Preappraised evidence-based reviews

Resources are now available that provide preappraised evidence-based reviews of selected medical and surgical clinical problems. The literature is reviewed for studies that meet rigid methodologic criteria. The body of evidence is then analyzed, interpreted and summarized by experts in the field. Examples of preappraised information sources are the electronic version of ACP Journal Club (available at www.acpjc.org) and the Cochrane Library (containing systematic reviews and a register of randomized controlled trials) at www.cochranelibrary.com (Fig. 3). The Cochrane Library emphasizes interventions, whereas the ACP Journal Club includes studies and reviews in the areas of etiology, prognosis, therapy, diagnosis, quality improvement and economics. Some authors are now suggesting that these resources of preappraised reviews may serve as the best place to begin a search of the literature.5

FIG. 3. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Prepared and published by Update Software, Oxford, UK.

The advantages of searching preappraised sources include more manageable search results containing high-quality studies or reviews. Clearly, if your clinical problem has been reviewed by a group of experts, and the literature has been appraised, you may have all the information you need. However, if your question has not been reviewed you will need to continue and complete a full MEDLINE search. Presently, more medical topics are addressed than surgical, but this situation is improving.

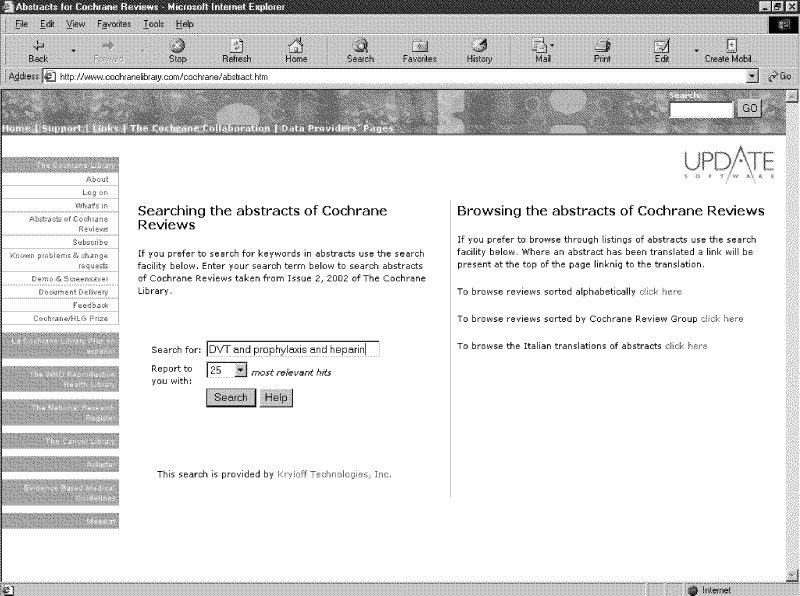

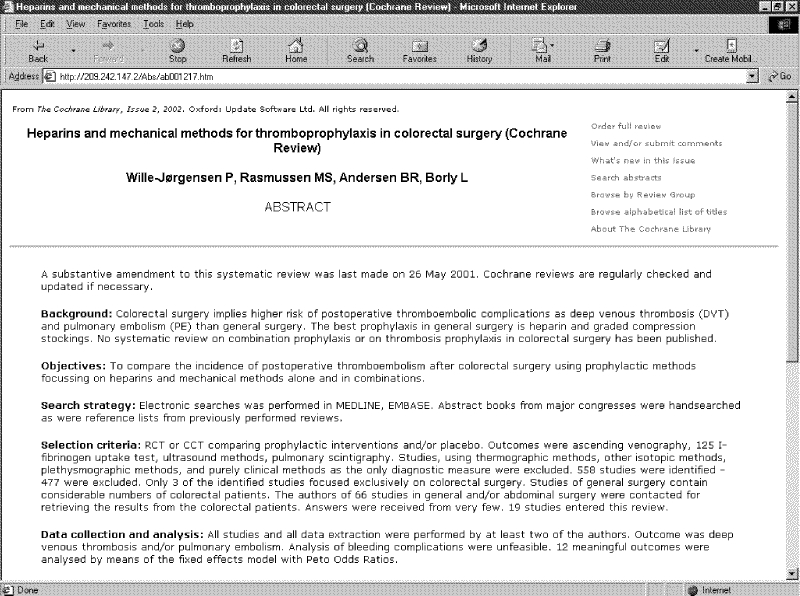

If we choose to review the preappraised evidence at “Cochrane Reviews,” we click on The Cochrane Library Web site, then “Abstracts of Cochrane Reviews,” and enter our text words in the “Search for” window. This identifies a recent review that proves extremely helpful (Fig. 4).6 The Cochrane review not only provides insight into the effectiveness of DVT prophylaxis with heparin but also specifically addresses the scenario of colorectal surgery. The reviewers conclude that combining heparin and mechanical methods (graded compression stockings) is the most effective means for reducing perioperative DVT and pulmonary embolism. Although some of the statistical terms may be unfamiliar to you, you understand the power of the conclusions.

FIG. 4. Abstract of an article on thromboprophylaxis in colorectal surgery obtained from the Cochrane Library. Prepared and published by Update Software, Oxford, UK.6

You remain concerned about the potential for increased hemorrhagic complications with the use of heparin and you wish to review the studies independently to clarify this issue. However, the thoroughness of this appraisal has done much to convince you to consider a change in your practice.

Executing a MEDLINE search

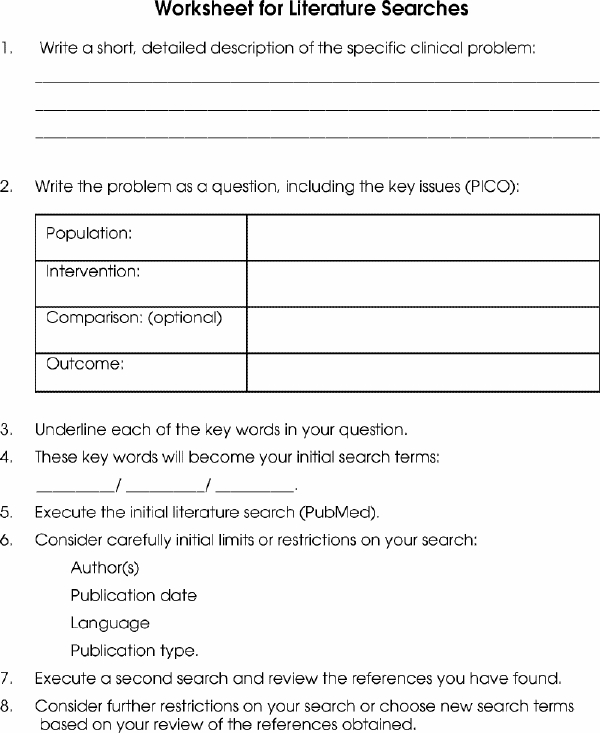

We have provided a simple worksheet to guide you through the process of developing and executing a literature search (Fig. 5). A simple method to search the literature is to use PubMed by accessing the PubMed home page www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed. You can enter your search terms in the search window directly or by using the “Preview/Index” feature. The search terms that you have selected from your clinical question are “text terms.” PubMed will search for each of these terms in the index fields (title, abstract) unless otherwise specified. PubMed will automatically combine these terms with the Boolean operator* “and,” which implies that all terms entered must be found in each record retrieved (which will restrict the focus of the search, whereas the Boolean operator “or” will expand the search).

FIG. 5. A sample worksheet for literature searches.

Another method of searching is to use medical subject headings (MeSH terms). Every article in the MEDLINE database is indexed according to its content with specific MeSH terms. As compared to a text word search, MeSH terms may increase the relevance of your search results. However, most surgeons will be unfamiliar the appropriate MeSH terms to apply to a search strategy. For certain topics, the consistency and accuracy of indexed MeSH terms may not be satisfactory and therefore you may not retrieve all relevant articles. To gain familiarity with MeSH terms, review specific terms associated with an abstract and conduct a new search using these terms. A librarian will also be extremely helpful if you choose to improve your knowledge of MeSH terminology, as will the NCBI MeSH Browser (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/meshbrowser.cgi).

Setting search limits

Text-word searching may result in large numbers of irrelevant references because of the various ways in which a particular word may be used in an abstract or title. If you are searching for a topic that is described in different ways, you may need to use synonyms for the disease or intervention. In these cases you would combine the terms with the Boolean operator “or.” Therefore, each record will include at least one of the synonyms chosen.

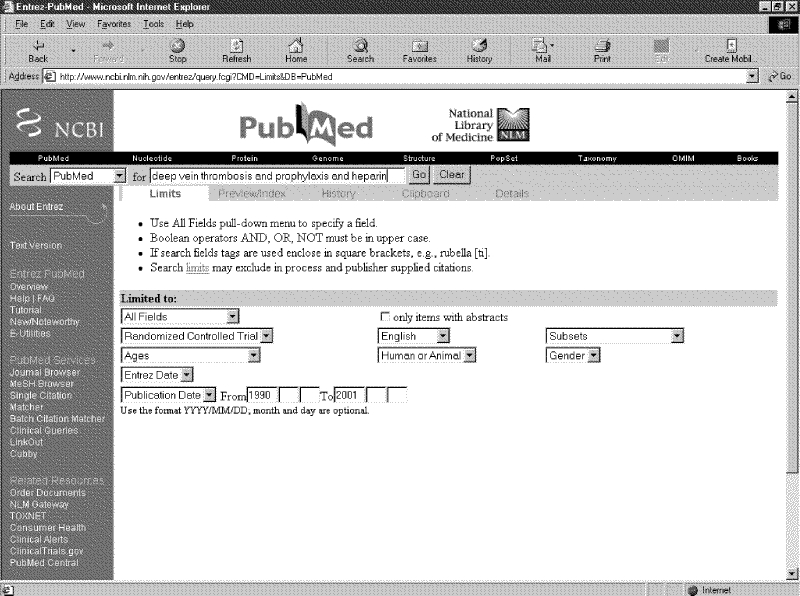

If your search leads to an unmanageable number of references, you should try to restrict or limit the search. This is a way of refining the search and increasing the relevance of each of the retrieved articles. For example, you may limit your search by specifying a certain publication type (i.e., randomized controlled trials), a specific interval of publication dates or by limiting the language of the publication to English. Other criteria that are helpful in eliminating less relevant articles include human or animal research articles, subsets of journals (e.g., nursing journals, dental journals), gender and availability of abstracts.

Choosing which limits to use will depend on your question. For therapy questions, limiting results by publication type is helpful (i.e., clinical trial, randomized controlled trial, multicentre study, review, meta-analysis or practice guideline). PubMed only allows you to apply one publication type at a time on the Limit page. To apply more than one publication type, you may use the Preview/Index page.

On the Preview/Index page you can select publication type in the drop-down box and type: clinical trial “or” randomized controlled trial “or” multicenter study “or” meta-analysis. This page is also useful to enter search terms for any field (all fields or limit to title, author, and so on) and have PubMed add the search criteria automatically to your search window (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6. Setting search limits in the PubMed search engine. Copyright of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Md.

Limiting the search by publication type is not as helpful with questions about etiology, diagnosis or prognosis. Search limits for age and gender will depend on the question. Limiting by language runs the risk of excluding an important piece of evidence. However, practical constraints may make it difficult to obtain or translate an article in another language. Keep in mind that MEDLINE usually provides an abstract in English for many studies published in other languages.

Clinical query filters

PubMed also provides clinical query filters, which use methodologic terms to limit search results to the areas of therapy, diagnosis, etiology, and prognosis. Click on “Clinical queries” at the PubMed home page to access these filters. You can choose to emphasize sensitivity (greater catch) or specificity (smaller catch) when selecting which filter to use. These filters are based on the work of Haynes and associates.7 Further study is underway to update these filters.

Sample search

In our example algorithm (Fig. 1) we have stated our clinical question as clearly as possible. After selecting key words to act as our initial search terms, we consider how we may choose to limit our search. For illustration, we ran a search with no limits on our key text words “deep vein thrombosis,” “prophylaxis” and “heparin.” This generated a list of 2184 articles. If we limit our search to only those articles describing randomized controlled trials published in English since 1990, we will reduce our list to 232 studies. It is reasonable at this point to review the titles and abstracts for some of the articles we have found by clicking on the title as displayed. This links us to the online written abstract. Scanning through several articles may help us to understand how to limit our search further without jeopardizing final content. After reviewing some of the abstracts we realize there is a wealth of knowledge and studies addressing the issue of DVT prophylaxis in all surgical specialties. Therefore, we choose to “raise the bar” on the publication type. We change the publication type from randomized controlled trial to meta-analysis and retrieve 29 articles.

We review these abstracts and find that the majority of references relate to orthopedic patients. However, a recent meta-analysis compares the use of various forms of heparin as DVT prophylaxis in general surgery (low molecular weight heparin v. unfractionated heparin and v. placebo).8 We review the abstract to find an impressive reduction in the risk for DVT following either form of prophylaxis. There may also be a slight increase in the risk of hemorrhagic complications; however, specific details are not provided in the abstract. We can record the reference to obtain the article for further review by either saving the abstract on our personal computer or printing the abstract directly from the browser window.

If we then change the publication type to practice guidelines, we retrieve 3 articles. One of these references is the guidelines from the American Society of Colorectal Surgeons.9 This reference is also recorded for review as little detail is given or recommendations provided in the abstract.

Summary

The Maintenance of Competence initiative (MOCOMP 2000) by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada provides a template for lifelong learning for all physicians and surgeons. The objectives include “… ensuring that fellows are engaged in professional development endeavours that are directed at enhancing the quality of specialty care.”10 The American College of Surgeons lists a commitment to lifelong learning as 1 of the 4 required elements for maintenance of certification.11 Professional development includes the ability to conduct a literature search to answer a clinical question or problem.

Having access to a personal computer and the Internet allows a surgeon to complete a literature search at the office or home. It is not difficult to perform a literature search, the challenge is to recognize when it is necessary and to find the time to complete it. It is no longer acceptable for a surgeon to be estranged from the current literature — the demands of colleagues, licensing bodies and patients necessitate satisfactory knowledge of the best available evidence for surgical care.

Now with your literature search complete and relevant articles reviewed, you make a decision to change your practice and provide heparin prophylaxis to prevent DVT in patients undergoing colorectal surgery. You make a further decision to explore future questions in clinical care with a literature review to decide upon possible changes in practice.

Correspondence to: Dr. Ved Tandan, Director, Surgical Outcomes Research Centre, St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton, Department of Surgery, Rm. G815, 50 Charlton Ave. E, Hamilton ON L8N 4A6; fax 905 521-6154; tandanv@mcmaster.ca

Accepted for publication Aug. 22, 2002.

Footnotes

*Although PubMed states that the Boolean operators must be capitalized, this is not necessary.

Correspondence to: Dr. Ved Tandan, Director, Surgical Outcomes Research Centre, St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton, Department of Surgery, Rm. G815, 50 Charlton Ave. E, Hamilton ON L8N 4A6; fax 905 521-6154; tandanv@mcmaster.ca

Accepted for publication Aug. 22, 2002.

References

- 1.Guyatt GH, Meade MO, Jaeschke RZ, Cook DJ, Haynes RB. Practitioners of evidence based care. Not all clinicians need to appraise evidence from scratch but all need some skills. BMJ 2000;320:954-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.McKibbon A, Eady A, Marks S. PDQ Evidence-based principles and practice. Hamilton (ON): B.C. Decker; 1999.

- 3.Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB, editors. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

- 4.Hunt DL, Jaeschke R, McKibbon. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXI. Using electronic health information resources in evidence-based practice. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 2000;283:1875-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Guyatt G, Rennie D, editors. Users' guides to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2002. p. 27-38.

- 6.Wille-Jørgensen P, Rasmussen MS, Andersen BR, Borly L. Heparins and mechanical methods for thromboprophylaxis in colorectal surgery (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Oxford: Update Software; 2002. issue 2.

- 7.Haynes RB, Wilczynski N, McKibbon KA, Walker CJ, Sinclair JC. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound studies in MEDLINE. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1994;1:447-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Mismetti P, Laporte S, Darmon JY, Buchmuller A, Decousus H. Meta-analysis of low molecular weight heparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism in general surgery. Br J Surg 2001;88:913-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.The Standards Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:1037-47. [PubMed]

- 10.The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada: Maintenance of Certification. Available http://rcpsc.medical.org/english/maintenance/programinfo/index.php3 (accessed 2003 Feb 5).

- 11.Nahrwold DL. The competence movement: a report on the activities of the American Board of Medical Specialties. Bull Am Coll Surg 2000;85(11):14-8. [PubMed]