Abstract

Background

The health risks associated with sickle cell trait are minimal in this sizable sector of the world's population, and many of these patients have no information about their sickle cell status. Splenic syndrome at high altitude is well known to be associated with sickle cell trait, and unless this complication is kept in mind these patients may be subjected to unnecessary surgery when they present with altitude-induced acute abdomen.

Methods

Four patients were admitted to the surgical ward with a similar complaint of acute severe left upper abdominal pain after arrival to the mountainous resort city of Abha, Saudi Arabia. All were subjected to splenectomy because of lack of suspicion regarding sickle cell status.

Results

Histologic examination of the spleen showed all patients had sickle cells in the red pulp. On further assessment all were found to have sickle cell trait with splenic infarction. In a similar study of 6 patients with known sickle cell disease who had comparable problems when they travelled to the Colorado mountains, all made an uncomplicated recovery with conservative management.

Conclusions

In ethnically vulnerable patients with splenic syndrome, sickle cell trait should be ruled out before considering splenectomy. These patients could respond well to supportive management, and splenectomy would be avoided.

Abstract

Contexte

Les risques pour la santé associés au trait drépanocytaire sont minimes dans ce segment important de la population mondiale et beaucoup de ces patients ne savent rien de leur statut à cet égard. Le lien entre le syndrome splénique à haute altitude et le trait drépanocytaire est bien connu et si l'on oublie cette complication, ces patients peuvent faire l'objet d'interventions chirurgicales inutiles lorsqu'ils se présentent avec un abdomen aigu causé par l'altitude.

Méthodes

On a admis en chirurgie quatre patients qui se plaignaient de la même chose, soit d'une douleur sévère aiguë à la partie supérieure gauche de l'abdomen à leur arrivée au centre de villégiature en montagne d'Abha, en Arabie saoudite. Tous ont subi une splénectomie parce qu'on ne soupçonnait pas du tout la présence d'une drépanocytose.

Résultats

L'analyse histologique de la rate a révélé la présence de drépanocytes dans la pulpe rouge chez tous les patients. Une analyse plus poussée a révélé que tous avaient le trait drépanocytaire avec infarctus de la rate. Une étude semblable portant sur six patients dont la drépanocytose était connue et qui avaient eu des problèmes comparables lorsqu'ils se sont rendus dans les régions montagneuses du Colorado a révélé que tous se sont rétablis sans complication après un traitement conservateur.

Conclusions

Chez les patients vulnérables au syndrome splénique à cause de leur origine ethnique, il faut exclure le trait drépanocytaire avant d'envisager une splénectomie. Ces patients pourraient bien répondre à une prise charge de soutien et l'on éviterait la splénectomie.

A patient is said to have sickle cell trait (SCT) when he or she inherits a normal hemoglobin (Hb) A gene from one parent and an abnormal HbS gene from the other parent. The prevalence of SCT is high, especially in equatorial Africa and in African-Americans. A rate of up to 50% has been reported in some enclaves of Africa and up to 10% in African-Americans.1,2,3 Twenty percent of the population in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia has SCT.4 Rare features or presentations of any common disease can have a remarkable medical impact when a large segment of the population is affected.

Patients with SCT are usually asymptomatic, not anemic, and generally enjoy a healthy life. Unless they have a strong family history, they may not be aware of their condition. However, there are specific problems that can affect these people, and proper management and advice can help them avoid unnecessary and usually unjustified measures.

Splenic syndrome at high altitude is one of the specific problems. It is usually seen after a patient with SCT has been travelling to mountainous areas.1,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 Unless the physician is aware of this problem, patients admitted with acute abdominal pain due to splenic infarction and sequestration might be subjected to unnecessary surgery.

I report here 4 adults who underwent splenectomy for unexplained left upper abdominal pain. None of them knew about their sickle cell status, and none gave any evidence of that possibility. Diagnosis was made usually when the histologic examination showed sickle cells in the red pulp of the spleen. In all patients the diagnosis of splenic syndrome secondary to SCT gene after exposure to high altitude was made retrospectively. I believe that these patients could have been saved surgery and instead been managed conservatively had the diagnosis been suspected. Others have reported the effectiveness of conservative therapy, but that was in patients who were known to have SCT.5 I now manage SCT patients with splenic syndrome by rest, reassurance, oxygen, hydration, analgesia and other supportive measures, with gratifying results.

Patients and methods

Some knowledge of the geography of Saudi Arabia is essential to imagine the events in this article. Contrary to the general belief, Saudi Arabia is not entirely hot arid desert. Along the western coastal plains and parallel to the Red Sea rises a series of mountains that reach more than 3050 m in the Asir region, with its capital city of Abha. Because of the pleasant weather in this area, especially in summer, tourism is an important factor in the regional economy. Recently, the World Health Organization selected Abha as the healthiest city in the Arab world.16

Case reports

Case 1

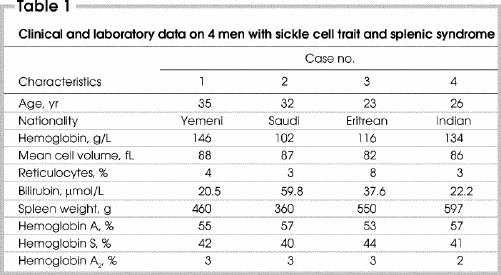

A 35-year-old Yemeni man was on a 2-week visit to the region. On the second day of his arrival, sudden severe left upper abdominal pain developed. He had no nausea, vomiting or chest pain. He denied any history of previous problems or hospital admissions with joint, bone or muscle pains. There was no relevant or family history of a similar illness. On examination, he was robust, fully conscious young patient who confined himself to his hospital bed and seemed to be in considerable pain. He was not pale or jaundiced. Vital signs were normal. His abdomen was tender in the left upper quadrant with some rigidity and rebound tenderness. The spleen was mildly enlarged 2 cm below the left costal margin and extremely tender to touch. All other body systems appeared normal. Initial laboratory investigations (Table 1) gave normal results except for a mild reticulocytosis and a high serum level of lactate dehydrogenase. A blood smear was unremarkable. Findings on chest radiography and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy appeared normal. His pain became excruciating, and results of investigations were not conclusive. Because of the lack of SCT in the patient or his family, the surgical team did not give consideration to the possibility of SCT. His pain remained progressive, and 48 hours after his admission, it was felt that he should undergo surgery for his acute abdomen. Laparotomy revealed a mildly enlarged spleen, which was removed. On the fourth postoperative day, the report on the histopathology of the spleen was available. The spleen was reported to be enlarged at 460 g and measured 18 х 12 х 5 cm. The capsule was intact, and the cut surface was dark brown without any nodularity. Microscopically, the red pulp and the blood vessels were markedly congested, with many areas of hemorrhagic infarction. The majority of the red cells were sickle shaped. The white pulp was inconspicuous.

Table 1

Based on the histologic findings, Hb electrophoresis was requested. The patient was retrospectively labelled as having SCT based on the presence of 42% HbS (Table 1). The abdominal pain was thought to arise from splenic syndrome secondary to splenic infarction and sequestration after spending time at high altitude.

Case 2

A 32-year-old Saudi man was seen in the outpatient department on the first day after his arrival from a coastal city. His main complaint was sudden, severe, progressive left hypochondrial pain exacerbated by breathing and particularly severe at the end of inspiration. On examination, the patient was a slightly pale young man who looked to be in severe pain. His breathing was shallow with exacerbation of pain during deep respiration. The spleen could be felt 5 cm below the left costal margin. Initial laboratory investigations showed mild anemia, neutrophilia and reticulocytosis (Table 1). No sickle cells could be seen.

Since no conclusive diagnosis could be made for his progressive pain, the surgical team recommended laparotomy with splenectomy on the second day of his admission.

Splenic histology and subsequent events were similar to those in case 1.

Case 3

A 23-year-old Eritrean man was seen in the jail ward, after illegally entering the country across the Red Sea. He complained of severe left upper abdominal pain with chest pain, cough and difficulty in breathing. On examination, he was in genuine pain with a very rigid upper abdomen, extremely tender spleen and shallow breathing. Initial laboratory testing showed that he was mildly anemic and slightly jaundiced (Table 1). No sickle cells could be seen in the blood smear. Hemoglobin electrophoresis was immediately requested. Chest radiography showed a pleural effusion and a left lower lobe infiltrate. The patient underwent splenectomy. The perioperative course and management were similar to those in cases 1 and 2.

Case 4

This 26-year-old man from southern India was admitted with a 6-hour history of severe, persistent upper abdominal pain that was initially localized to the epigastrium. The patient had been working in one of the mountain cities of the region until a short while before his illness when he visited the lowlands of the Red Sea. On his return to high altitude, he started to experience abdominal pain. On examination, he appeared healthy but in extreme pain. The course of his illness, assessment and management were similar to those of cases 1 to 3. This patient underwent surgery the next day. The findings on histologic examination were reported as hemorrhagic infarctions and congestive splenomegaly.

Discussion

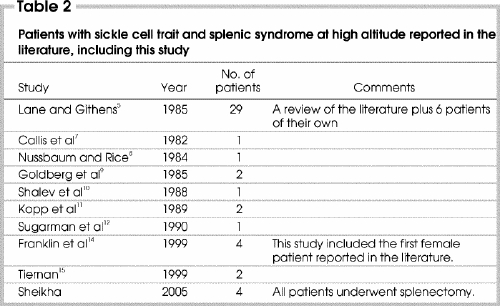

The occurrence of splenic infarction occurring at high altitude has been reported in 43 patients with SCT.1,2,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 Table 2 5,7,8,9,10,11,12,14,15 revises a 1985 literature review by Lane and Githens5 and summarizes all the subsequent published cases. With our report, the total number of documented cases is 47. Our report is unique because all of our patients were subjected to surgery, which seems to be inappropriate for a medically manageable condition.

Table 2

The standard scenario of splenic syndrome in patients with SCT is as follows. Patients usually do not know about their sickle cell genetic status, and most of them have never had any problems. Shortly after arrival to an area of high altitude, upper abdominal pain develops that soon localizes itself to the splenic region in the left hypochondrium. The spleen is usually enlarged from sequestration of red cells and becomes very tender from vaso-occlusion by sickled red cells, resulting in splenic infarction. The abdomen becomes rigid, with muscle guarding and, often, rebound tenderness. In many of these patients pleural effusion can develop, especially on the left side, and a few can even have pulmonary infiltration. Breathing thus becomes shallow, difficult and often painful, especially at the end of inspiration. Anemia may accompany this presentation, and reticulocyte count and serum lactate dehydrogenase enzyme levels may increase.

Our report documents 4 SCT patients who underwent splenectomy shortly after their arrival at an altitude of more than 3050 m. They had no idea about their genetic disorder and never had a comparably severe problem. They all presented with left upper abdominal pain that had no explainable cause. Surgery was scheduled based on the finding of an unexplainable acute abdomen in a young adult. Had the possibility of splenic syndrome secondary to exposure to high altitude in a patient with SCT been considered, the majority of those operations would have been avoided. In a similar study of 6 known patients with SCT who had the same problem after travelling to the Colorado mountains, all responded to conservative management.5

This problem seems to be limited to visitors rather than to local residents. Two intriguing studies from the Asir region have demonstrated that none of the indigenous population with SCT ever suffered from splenic syndrome although they lived permanently in a mountainous area.17,18 One of those studies involved 143 patients with SCT, who were closely followed up. Although it was reported that patients with sickle cell anemia (HbSS) who lived at high altitude were twice as symptomatic as their comparable lowlanders, no patient with SCT at either altitude was diagnosed with splenic syndrome. All of the patients reported here were on short visits when their crises developed. In high altitude resorts, where the economy depends on tourism, this issue should be well addressed by every physician working in the area.

Splenic syndrome seems to be restricted to patients with SCT (HbAS) rather than sickle cell anemia (HbSS). The fact that the spleen is atrophic because of repeated vaso-occlusive crises in the majority of patients with HbSS could well explain this paradox. Even within the SCT spectrum, the degree of susceptibility to splenic syndrome seems to depend on the proportion of HbS present. Patients with SCT have 2 main Hbs: HbA and HbS. HbA2 is a minor component. Patients always have more HbA than HbS, but what is important is the real percentage of HbS. In many populations, a trimodal distribution of values for the percentage of HbS is observed in SCT patients, with means around 41%, 35% and 28%.1,19 This variation explains the racial differences in susceptibility of SCT patients to splenic syndrome at high altitude. Splenic syndrome has been found to be less common in black SCT patients than non-blacks.1,5,6 HbS ratio is modulated by other genetic abnormalities like inheritance of α-thalassemia gene, which affects almost one-third of black people and is extremely rare in white people.1 Coinheritance of the α-thalassemia gene reduces the proportion of HbS and gives protection against sickling at high altitude. The majority of patients reported with splenic syndrome have more than 40% HbS.1,5,20 This could well be explained by lack of this concomitant protective genetic abnormality.1,5,6

Another interesting point is that almost all the reported patients, including the 4 reported here, with splenic syndrome in SCT were male!1,5 Only 1 female patient has been reported.14

It seems that the relatively stagnant anoxic and acidotic milieu in the red pulp of the spleen, where circulation could reach the point of standstill, especially when there is splenomegaly, is ideal for HbS polymerization, red cell sickling and vaso-occlusion.21 The main pathophysiological cause of splenic syndrome is vascular infarction due to vaso-occlusion by sickled cells, which may also be associated with splenic sequestration leading to a more marked splenomegaly. This creates an ideal milieu for more red cells to get sickled, thus promoting the cycle of sickling, vaso-occlusion and infarction.1

Although all of our patients with splenic syndrome showed sickle cells in the congested vasculature of the splenic red pulp and in many of them that prompted investigation of the patient for SCT, it is important to note that the autopsy finding of sickled red cells in the spleen does not per se incriminate this phenomenon as the reason for this complication.1 Postmortem sickling is expected and does not, in itself, mean that antemortem sickling led to the splenic syndrome.22 When one combines the whole clinical and histologic picture, then a more reliable conclusion can be reached.

Conclusions

Although splenic syndrome is a rare complication of the common genetic abnormality SCT, it is important to rule out this possibility when an ethnically vulnerable patient presents with acute abdominal symptoms. Patients who have had similar problems in the past or become anemic during the process need stringent evaluation. With the cosmopolitan nature of many communities, proper laboratory evaluation is recommended. Once a diagnosis of SCT is established, conservative measures could obviate surgical management. Splenectomy should be discouraged in SCT patients presenting with splenic syndrome at high altitude. Supportive care should always be the primary treatment.

Published as abstract 3125 in Blood 1998;92[Suppl 1]:34-5b at the 40th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Miami Beach, Fla., Dec. 4, 1998.

Acknowlegements: I thank Ziyan T. Salih, MD, from the Department of Pathology, the Mississippi Medical Centre, for her continued support, encouragement, literature search and critical review of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Anwar Sheikha, 129 Country Club Dr., Madison MS 39110; fax 601 605-9827; anwarsheikha@msn.com

Accepted for publication June 4, 2004.

References

- 1.Sears DA. Sickle cell trait. In: Embury SH, Hebbel RP, Mohandas N, Steinberg MH, editors. Sickle cell disease: basic principles and clinical practice. New York: Raven Press; 1994. p. 381-94.

- 2.Sears DA. The morbidity of sickle cell trait. A review of the literature. Am J Med 1978;64:1021-36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Serjeant GR. Sickle cell disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1985.

- 4.Salamah MM, Mallouh AA, Hamdan JA. Acute splenic sequestration crises in Saudi children with sickle cell disease. Ann Trop Paediatr 1989;9:115-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Lane PA, Githens JH. Splenic syndrome at mountain altitude in sickle cell trait. Its occurrence in nonblack persons. JAMA 1985;253:2251-4. [PubMed]

- 6.Castro O, Finch SC. Splenic infarction in sickle cell trait: Are whites more susceptible? N Engl J Med 1974;291:630-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Callis M, Petit JJ, Jordan C, Vives- Corrons JL, Ferran C. Splenic infarction in a white boy with sickle cell trait. Acta Haematol 1982;67:232. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Nussbaum RL, Rice L. Morbidity of sickle cell trait at high altitude. South Med J 1984;77:1049-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Goldberg NM, Dorman JP, Riley CA, Armbruster EJ Jr. Altitude-related splenic infarction in sickle cell trait — case reports of a father and son. West J Med 1985;143:670-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Shalev O, Boylen AL, Levene C, Oppenheim A, Rachmilewitz EA. Sickle cell trait in a white Jewish family presenting as splenic infarction at high altitude. Am J Hematol 1988;27:46-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kopp P, Negri M, Wegmuller E, Cottier P. [2 cases of acute sickle cell crisis in subjects with sickle cell trait following high altitude exposure.] Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1989;119:1358-9. [PubMed]

- 12.Sugarman J, Samuelson WM, Wilkinson RH Jr, Rosse WF. Pulmonary embolism and splenic infarction in a patient with sickle cell trait. Am J Hematol 1990; 33:279-81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Steinberg MH. Sickle cell trait and splenic syndrome. JAMA 1985;254:1901-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Franklin QJ, Wright SW, Kent LP. Splenic syndrome in sickle cell trait: four case presentations and a review of the literature. Mil Med 1999;164:230-3. [PubMed]

- 15.Tiernan CJ. Splenic crisis at high altitude in 2 white men with sickle cell trait. Ann Emerg Med 1999;33:230-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Abha: the top health city in the Arab world. Al-Eqtisadiah [The Economist] 2003:3531.

- 17.Addae S, Adzaku F, Mohammed S, Annobil S. Sickle cell disease in permanent residents of mountain and low altitudes in Saudi Arabia. Trop Geogr Med 1990; 42:342-8. [PubMed]

- 18.Addae S, Adzaku F, Mohammed S, Annobil S. Survival of patients with sickle cell anemia living at high altitude [letter]. South Med J 1990;83:487. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Huisman TH. Trimodality in the percentages of beta chain variants in heterozygotes: the effect of the number of active Hbalpha structural loci. Hemoglobin 1977; 1: 349-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Rotter R, Luttgens WF, Peterson WL, Stock AE, Motulsky AG. Splenic infarction in sicklemia during flight: pathogenesis, hemoglobin analysis and clinical features of six cases. Ann Intern Med 1956; 44:257-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Groom AC, Levesque MJ, Nealon S, Basrur S. Does an unfavorable metabolic environment for red cells develop within cat spleen when abnormal cells become trapped? J Lab Clin Med 1985;105:209-13. [PubMed]

- 22.James CM, Jenkins GC, Stephens AD. Sickle cell trait [editorial]. Med Sci Law 1989;29:1-3. [DOI] [PubMed]