Abstract

Objective:

Religious practices among adults are associated with more 12-step participation which, in turn, is linked to better treatment outcomes. Despite recommendations for adolescents to participate in mutual-help groups, little is known about how religious practices influence youth 12-step engagement and outcomes. This study examined the relationships among lifetime religiosity, during-treatment 12-step participation, and outcomes among adolescents, and tested whether any observed beneficial relation between higher religiosity and outcome could be explained by increased 12-step participation.

Method:

Adolescents (n = 195; 52% female, ages 14–18) court-referred to a 2-month residential treatment were assessed at intake and discharge. Lifetime religiosity was assessed with the Religious Background and Behaviors Questionnaire; 12-step assessments measured meeting attendance, step work (General Alcoholics Anonymous Tools of Recovery), and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA)/Narcotics Anonymous (NA)-related helping. Substance-related outcomes and psychosocial outcomes were assessed with toxicology screens, the Adolescent–Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale, the Children's Global Assessment Scale, and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory.

Results:

Greater lifetime formal religious practices at intake were associated with increased step work and AA/NA-related helping during treatment, which in turn were linked to improved substance outcomes, global functioning, and reduced narcissistic entitlement. Increased step work mediated the effect of religious practices on increased abstinence, whereas AA/NA-related helping mediated the effect of religiosity on reduced craving and entitlement.

Conclusions:

Findings extend the evidence for the protective effects of lifetime religious behaviors to an improved treatment response among adolescents and provide preliminary support for the 12-step proposition that helping others in recovery may lead to better outcomes. Youth with low or no lifetime religious practices may assimilate less well into 12-step–oriented treatment and may need additional 12-step facilitation, or a different approach, to enhance treatment response.

For a substantial proportion of youth, initial experimentation with alcohol and other drugs quickly escalates into severe problems that can have immediate and long-term consequences (Aarons et al., 1999; Fombonne, 1998; Fowler et al., 1986; Tapert and Brown, 2000). In fact, substance use disorders (SUDs) typically start during adolescence and peak during young adulthood (Dawson et al., 2004; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010). Because the duration and impact of SUDs are minimized the sooner treatment begins (Dennis et al., 2005), providing effective adolescent intervention has become a public health priority (Physician Leadership on National Drug Policy, 2002). However, despite the obvious social and public health gains to be made from earlier intervention and some promising initiatives to establish efficacious adolescent SUD treatments (Dennis et al., 2004), comparatively little information is available regarding adolescents’ response to SUD treatment and which factors influence such response.

Twelve-step participation

SUDs among treatment-seeking samples tend to be chronic (Brown et al., 2011; Hser and Anglin, 2011; McLellan et al., 2000). Consequently, a major goal of most treatment programs for both adolescents and adults is to prevent relapse by facilitating engagement with continuing care resources, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) (Humphreys, 2004; Kelly, 2003; Knudsen et al., 2009; Roman and Blum, 1999; Tonigan et al., 1996). In nationally representative U.S. treatment surveys, most SUD programs for youth include an eclectic mix of cognitive-behavioral, family-based, and motivational interventions (Knudsen et al., 2009). These survey data also reveal that nearly half (47%) require participation in 12-step mutual help groups during treatment, and 85% link adolescents with AA or NA groups as a continuing care resource at discharge (Kelly and Yeterian, 2008; Knudsen et al., 2008). Rigorously conducted research studies with adults and adolescents have shown that use of these free and widely available community resources can help individuals maintain recovery and also reduce the financial burden on the health care system (Chi et al., 2009; Humphreys and Moos, 2001, 2007; Kelly et al., 2008). Importantly, 12-step participation during treatment has been shown to increase the likelihood of continued 12-step participation and better outcomes not only for adults (Kaskutas et al., 2009; Kelly and Moos, 2003; Litt et al., 2009; Walitzer et al., 2009) but also for adolescents (Alford et al., 1991; Chi et al., 2009; Kelly et al., 2000, 2002, 2008, 2010; Kennedy and Minami, 1993).

Although 12-step participation is seen as a valuable addition to adolescent treatment (Knudsen et al., 2008), little is known about the factors that may influence youth engagement in 12-step organizations. Spiritual and religious variables have served as prime candidates to investigate as potential patient factors that might influence response to 12-step treatment (Connors et al., 2001) because 12-step organizations are explicitly spiritual by design. These organizations posit that the change that is necessary for recovery from SUDs is achieved by a “spiritual awakening” or “spiritual experience” characterized in large part by substituting self-preoccupation with a program of helping other sufferers (AA, 2001). This requires the adoption of new attitudes and behaviors that are incompatible with an intoxicated lifestyle and that facilitate attributing new meaning to life stress, further supporting abstinence and recovery (AA, 1953; Kelly et al., 2011).

Influence of religiosity on 12-step participation and treatment response

Empirical evidence indicates that religious/spiritual behaviors are also linked to reduced risk of relapse and improved posttreatment outcomes (Avants et al., 2001; Booth and Martin, 2001; Carter, 1998; Flynn et al., 2003; Moos, 2007; Pardini et al., 2000; Polcin and Zemore, 2004; Zemore and Kaskutas, 2004). Religious/spiritual behaviors have been examined as a treatment matching variable in Project MATCH (Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity; e.g., randomization to 12-step–facilitated treatment). In keeping with theories of cognitive dissonance and equilibrium (Festinger, 1957), those with elevated religiosity/spirituality may be more comfortable with the spiritual principles emphasized in AA/NA and may be more likely to adopt the program's suggested practices, which in term may lead to better outcomes. However, although several studies have been conducted among treatment-seeking adults (Connors et al., 2001; Kelly et al., 2006; Winzelberg and Humphreys, 1999), it is unclear how religiosity/spirituality may influence adolescent 12-step participation during treatment and outcomes.

Study aims

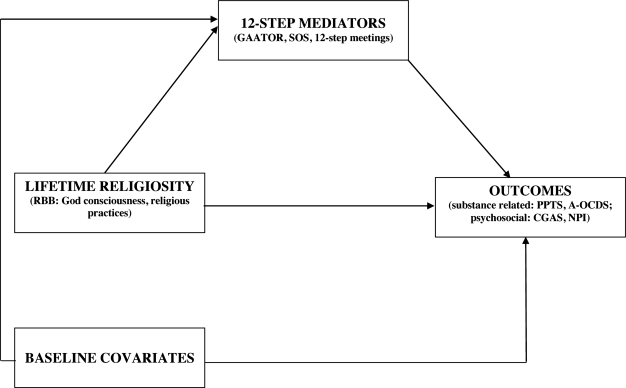

This study examines how lifetime religiosity/spirituality influences 12-step meeting attendance, work on the 12 steps, AA/NA-related helping during treatment, and how these behaviors may in turn affect substance-related and psychosocial improvements among adolescents court-referred for residential treatment. As shown in Figure 1, we hypothesize that youth entering treatment with elevated lifetime religiosity/spirituality will engage more in these 12-step behaviors during treatment and show more improvement at the end of treatment. We also predict that greater 12-step participation during treatment will result in better substance-related and psychosocial outcomes and that the relationship between religiosity/spirituality and improved outcomes will be mediated by 12-step participation.

Figure 1.

Tested mediational model of the influence of lifetime religiosity on 12-step participation and treatment response. GAATOR = General Alcoholics Anonymous Tools of Recovery; SOS = Service to Others in Sobriety; RBB = Religious Beliefs and Behaviors; PPTS = percentage positive toxicology screens; A-OCDS = Adolescent-Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale; CGAS = Children's Global Assessment Scale; NPI = Narcissistic Personality Inventory.

Method

Procedures

Recruitment for this study was conducted from February 2007 to August 2009 at New Directions, the largest adolescent residential treatment provider in northeast Ohio. Inclusion criteria included the following: ages 14–18 years; English speaking; stable address and telephone; met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), diagnosis of an SUD; and medically stable. Exclusion criteria included a major chronic health problem other than substance use likely to require hospitalization, currently suicidal or homicidal, and expected incarceration in the subsequent 12 months. Subjects were referred to treatment from a variety of sources, including juvenile court (83%), mental health professionals (65%), and nonpsychiatric physicians (2%). Subjects were admitted into treatment 1 week after a 3-day detoxification (if required). In the week before their scheduled date of admission, subjects were sent a packet of information with an invitation letter to participate in the study. Following admission, subjects were approached to participate in the study. After a complete description of the study, eligible subjects signed statements of informed consent/assent. Ninety-minute baseline interviews were conducted within the initial 10 days of treatment and repeated at discharge after an average of 2.2 months of residential treatment. Subjects were paid $25 for completed assessments. All procedures of this study were approved by the University Hospitals/Case Medical Center Institutional Review Board for human investigation, and a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism was obtained.

Setting

New Directions is a 24-hour monitored, intensive residential treatment program that provides a range of evidenced-based therapeutic modalities, including cognitive behavioral therapy; motivational enhancement therapy; reality therapy; adolescent community reinforcement approaches; gender-specific treatment; medication-assisted treatment; relapse prevention; family, individual, and group therapies; and assertive continuing care (aftercare). Using the Drug and Alcohol Program Treatment Inventory (Swindle et al., 1995), the top five treatment modalities at the site are cognitive-behavioral (M = 11.0), psychodynamic (M = 11.0), therapeutic community (M = 10.0), family (M = 9.0), and 12-step facilitated (M = 9.0). Clients in residential treatment spend approximately 20 hours per week in therapeutic activities.

Subjects

A total of 482 adolescents were admitted into treatment during the enrollment period of the study. Because clients are admitted into the facility 7 days a week between the hours of 8 A.M. and 8 P.M., it was not possible to have research staff available at all times when youth were admitted into the treatment facility. However, all youth with scheduled admission appointments and those unscheduled occurring during regular weekday hours (8 A.M.–6 P.M.), one weekday evening (5 P.M.–8 P.M.), and one weekend day (9 A.M.–5 P.M.) were approached by research staff. Of the 211 patients approached, none were ineligible and 16 refused to participate, resulting in an enrollment sample of 195 subjects. There were no significant differences between adolescents enrolled (n = 195) and not enrolled (n = 287) in terms of demographic characteristics, substance use severity, years of illicit drug use, trauma and sexual history, medication and treatment history at intake, as well as likelihood of residential treatment completion. There were more girls in the enrollment sample (50%) than in the population not enrolled (17%, p < .0001) because of the gender stratification of the study design (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of enrolled and non-enrolled patients on demographic and clinical variables

| Variable | Total (N = 482) M (SD) or n (%) | Not enrolled (n = 287) M (SD) or n (%) | Enrolled (n = 195) M (SD) or n (%) |

| Demographic variables | |||

| Age, in years | 16.28 (1.00) | 16.29 (0.96) | 16.29 (1.04) |

| Female | 148 (31%) | 50 (17%) | 98 (50%)† |

| Minority background | 176 (37%) | 114 (40%) | 62 (32%) |

| Hispanic background | 11 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 4 (2%) |

| Monthly household income, in U.S. $ | 2,296 (1,944) | 2,247 (1,762) | 2,353 (2,147) |

| Parental divorce | 206 (43%) | 115 (40%) | 91 (47%) |

| Juvenile justice involvement | 420 (88%) | 252 (88%) | 168 (87%) |

| Attend alternative high school | 60 (13%) | 34 (12%) | 26 (13%) |

| Adolescent parent | 26 (5%) | 20 (7%) | 6 (3%) |

| Clinical variables | |||

| Years of use | 2.93 (0.99) | 2.86 (0.99) | 3.03 (0.97) |

| Drug of choice: Alcohol | 49 (10%) | 27 (9%) | 22 (11%) |

| Drug of choice: Marijuana | 392 (81%) | 242 (84%) | 150 (77%) |

| Drug of choice: Other | 41 (9%) | 18 (6%) | 23 (12%) |

| Incest history | 6 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (2%) |

| Physical abuse history | 73 (15%) | 45 (16%) | 28 (15%) |

| Sexual abuse history | 59 (12%) | 29 (10%) | 30 (15%) |

| Familial substance misuse | 284 (59%) | 172 (60%) | 112 (58%) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 15 (3%) | 8 (3%) | 7 (4%) |

| Perpetrated domestic violence | 55 (11%) | 27 (9%) | 28 (15%) |

| Witnessed domestic violence | 46 (10%) | 23 (8%) | 23 (12%) |

| Victim of domestic violence | 32 (7%) | 14 (5%) | 18 (9%) |

| On psychotropic medication | 235 (49%) | 135 (48%) | 99 (52%) |

| HIV/AIDS positive | 2 (0.4%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Completed treatment | 407 (84%) | 237 (83%) | 175 (87%) |

p <.0001.

Measures

Data were gathered via rater-administered, semi-structured interviews; medical chart review; biomarkers; and youth, parent, and clinician reports. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in person by experienced clinical interviewers whose training and certification ranged from bachelor's level to doctor of medicine. All individuals involved in collecting data from subjects completed National Institutes of Health–required courses on human subjects’ protection. Background characteristics, lifetime religiosity, and substance use severity were assessed at baseline. Twelve-step mediators and study outcomes were assessed at intake and at discharge.

Background characteristics of subjects included age, gender, race, ethnicity, parental marital status (single vs. not single), parental education, and felony history in the 2 years before intake. Felony history was assessed using adapted items from the Teen Treatment Services Review (Kaminer et al., 1998). The Teen Treatment Services Review has demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability with adolescent alcohol populations (Kaminer et al., 1998).

Religiosity was assessed using two lifetime subscale scores from the 14-item self-report Religious Beliefs and Behaviors questionnaire (Connors et al., 1996): “God consciousness” and “formal religious practices.” This questionnaire was chosen because items were congruent with 12-step practices (i.e., prayer, meditation, thinking about God) to allow testing of 12-step–related theory, its frequent use in SUD research (e.g., Project MATCH), and good psychometric properties (Goggin et al., 2007). God consciousness is derived from the sum of one item rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (atheist, no belief in God) to 4 (practiced religion, belief in God) and two items rated on a 3-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 2 (yes, past and current), for a total score ranging from 0 to 8. Formal religious practices is derived from the sum of four items, each rated on a 3-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 2 (yes, past and current), for a total score ranging from 0 to 8. In the current sample, the correlation between the lifetime Religious Beliefs and Behaviors subscales was moderate (r = .49, p < .001).

Substance use severity indices associated with treatment outcomes included treatment history and readiness for change (Morgenstern et al., 1997; Pagano et al., 2009a). Treatment history in the previous 24 months was assessed using select items from the valid and reliable Health Care Data Form (Larson et al., 1997; Zywiak et al., 1999). Readiness for change was assessed with the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment scale, a measure of motivation for behavioral change that has been validated with treatment-seeking young adults and adults (DiClemente et al., 2004; Dozois et al., 2004; Dunn et al., 2003; McConnaughy et al., 1989; Miller et al., 2002). With reference to the past month, 32 items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strong disagreement) to 5 (strong agreement). A readiness-to-change score is formed from the sum of three subscale scores (contemplation, action, and maintenance) minus the precontemplation subscale, with scores ranging from 0 to 105 (DiClemente et al., 2001).

Twelve-step mediators.

Three 12-step mediators were assessed using the General Alcoholics Anonymous Tools of Recovery (GAATOR), Service to Others in Sobriety (SOS), and total number of meetings attended. The GAATOR is a 24-item self-report of the practice of the 12 steps in daily living. With reference to the past 90 days, each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (definitely false) to 4 (definitely true) and summed for a total score (range: 0–72). The total GAATOR score has shown good to excellent internal consistency, significant association with increased abstinence (Montgomery et al., 1995; Tonigan et al., 2000), and good internal reliability with the current sample (Cronbach's α > .80). The SOS (Pagano et al., 2010b) is a 12-item self-report of AA/NA-related helping; each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (rarely) to 5 (always) and summed for a total SOS score (range: 12–60). At intake, youth completed the SOS because they were the best informants of AA/NA-related helping before treatment. At the end of treatment, each subject's primary counselor rated the youth's AA/NA-related helping participation as observed over the 2-month treatment period. The SOS has demonstrated good psychometric properties with treatment-seeking samples, significant association with increased abstinence (Pagano et al., 2009a; Pagano et al., 2010b), and good internal reliability with the current sample α = .88). Meeting attendance was assessed with one item from the GAATOR, “During the past 90 days, how many 12-step meetings have you attended?” Intercorrelations between 12-step mediators were small (rs = .09–.13; Table 2).

Table 2.

Twelve-step mediators and outcomes at discharge

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. |

| Twelve-step mediators | ||||||||||

| 1. General Alcoholics Anonymous Tools of Recovery | – | .12* | .13* | −.12* | −.06 | −.10* | −.01 | −.10* | −.07 | −.05 |

| 2. Service to Others in Sobriety | – | >– | .09 | −.02 | −.13* | −.10* | −.03 | −.14** | −.04 | .11* |

| 3. Meeting attendance | – | – | – | −.01 | .08 | .11 | −.02 | −.05 | −.10 | −.06 |

| Substance-related outcomes | ||||||||||

| 4. Percentage positive toxicology screens | – | – | – | −.01 | −.06 | −.13* | .04 | −.10 | .06 | |

| 5. Irresistibilitya | – | – | – | – | – | .66*** | .11* | .06 | −.02 | −.09 |

| 6. Interferencea | – | – | – | – | – | – | .10* | .07 | −.02 | −.09 |

| Psychosocial outcomes | ||||||||||

| 7. Exhibitionismb | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .13* | .27*** | −.01 |

| 8. Entitlementb | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .09 | −.01 |

| 9. Vanityb | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .05 |

| 10. Children's Global Assessment Scale | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Levels at discharge, ratio scale | ||||||||||

| M | 73.0 | 33.7 | 32.1 | 0.16 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 60.7 |

| (SD) | (11.1) | (8.6) | (15.5) | (1.9) | (0.4) | (5.0) | (1.9) | (1.1) | (1.1) | (6.1) |

| Change from baseline, ratio scale | ||||||||||

| M | 9.4 | 7.5 | 24.0 | – | −15.5 | −9.6 | −0.4 | −0.4 | −0.2 | 11.2 |

| (SD) | (13.2) | (12.7) | (17.4) | – | (7.2) | (6.5) | (1.7) | (1.5) | (0.9) | (5.7) |

| t | −7.7*** | −7.8*** | −15.7*** | – | 26.7*** | 18.2*** | 3.0*** | 1.7 | 0.2 | −23.6*** |

Subscale of the Adolescent–Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale;

subscale of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Study outcomes.

Substance-related and psychosocial outcomes were assessed at the end of treatment. Three substance-related outcomes included urine toxicology screens, an objective SUD biomarker, and two subscales of craving symptomatology, an outcome often assessed in clinical trials developing anti-craving medications and shown to be predictive of relapse (MacKillop et al., 2010; Sinha and O'Malley, 1999). Urine toxicology screens were collected by clinical staff prospectively over the course of treatment. A variable calculating the percentage positive toxicology screens (PPTS) was determined by dividing the total number of positive screens by the total number of tests given; considering the variable's skewed distribution, PPTS received an arsine transformation, as was done for primary outcome analyses in Project MATCH (Project MATCH Research Group, 1997; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). Derived from the 14-item self-report Adolescent–Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (A-OCDS; Deas et al., 2001) were the two craving subscales, interfering craving symptoms (range: 0–25) and irresistible craving symptoms (range: 0–33). The A-OCDS has shown good internal consistency with adolescent alcohol populations (Anton et al., 1995; Deas et al., 2002) and the current sample (Cronbach's α > .85). The two A-OCDS subscales were moderately correlated (r = .66; Table 2).

Four psychosocial outcomes were assessed with the well-validated instruments: the clinician-rated Children's Global Assessment Scale (range: 1–100; Dyrborg et al., 2000; Rey et al., 1995; Shaffer et al., 1983) and the 40-item Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; Bird et al., 1987; Del Rosario and White, 2005; Exline et al., 2004; Raskin and Hall, 1979; Raskin and Terry, 1988; Samuel and Widiger, 2008; Shaffer et al., 1983). Three NPI subscales shown to be elevated in substance-dependent populations were selected (Pagano et al., 2010a): exhibitionism (range: 0–7), entitlement (range: 0–6), and vanity (range: 0–3). The NPI has demonstrated adequate construct validity (Exline et al., 2004; Raskin and Terry, 1988; Shulman and Ferguson, 1988), good internal consistency (α = .82; Exline et al., 2004), and good test–re-test reliability (rs = .57–.81; Del Rosario and White, 2005) among young adult populations. As shown in Table 2, there were significant small correlations between NPI subscales (rs = .09–.27) and small correlations between NPI-exhibitionism and substance-related outcomes (rs = .10–.13).

Statistical analytic plan

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), using the PROC CORR, PROC FREQ, PROC TTEST, PROC REG, and PROC GLM procedures. Depending on the type of variables (continuous or discrete), Fisher's Exact Test for binary variables or the Kruskal–Wallis chi-square test for continuous variables was performed to evaluate differences between subjects. Distributions of variables were examined for normality. Missing data for key variables at discharge ranged from 0.05% to 9.5%, and outcomes collected from medical charts were obtained for all subjects. The family-wise error rate for the two sets of outcomes was set at .05 (two tailed).

For tests of mediation, three significant direct effects must be found: (a) there is a statistically significant association between the predictor (religiosity) and outcome, (b) there is a significant association between the predictor and the mediator (12-step involvement during treatment), and (c) there is a significant association between the mediator and the outcome. Following Baron and Kenny's (1986) procedures, we first assessed the alpha (α) path, the effect of lifetime Religious Beliefs and Behaviors subscale scores on 12-step mediators. We then assessed the beta (β) path, the effect of 12-step mediators on study outcomes (controlling for baseline confounding variables/covariates). If both the alpha (α) and beta (β) paths jointly showed significance at the .05 level, there was evidence for a significant mediating relationship (e.g., Religious Beliefs and Behaviors affects the outcome variable through changes in the 12-step mediating variables) (MacKinnon, 1994). The mediated effect is the product of the alpha and beta (αβ) values and provides an estimate of the relative strength of the mediated effects. Mediation is demonstrated when the effect of the predictor on outcome is no longer significant or substantially reduced when controlling for the mediator (e.g., 12-step meeting attendance). Bentler's comparative fit index (Bentler, 1990) and the Bentler–Bonett nonnormed fit index (Bentler and Bonett, 1980) were above the recommended level of .90, with values close to .95 (Allison, 2005; Byrne, 2001). Background characteristics significantly associated with either 12-step involvement or treatment outcomes—including age, race, readiness for change, felony history, treatment history, parental marital status, and parental education (Pagano et al., 2009b)—were controlled for in all analytic models. Variables were mean centered to reduce multicollinearity (Aiken and West, 1991).

Results

Sample description

Table 3 shows the sample of 195 substance-dependent youth at baseline. The majority of youth entered treatment with marijuana dependence (92%), and 61% met the criteria for alcohol dependence. Comorbidity of alcohol dependency with drug dependency occurred in 60% of the sample. The most prevalent drug dependency types comorbid with alcohol dependency were marijuana (59.5%) and narcotics (21.0%). The average age was 16.2 years, and approximately half of the sample was male (48%) and from a single-parent household (50%). Thirty percent were African American, and 8% were Hispanic. Eighty-five percent had a history of parole/probation, with an average of 0.5 felonies in the previous 2 years. Approximately half of the sample (49%) identified themselves as Christian, 28% were spiritual with no religious denomination, 20% were atheist or agnostic, 2% were Muslim, and one subject (1%) was Buddhist. Few had received prior SUD treatment (5% reported prior residential treatment, and 8% reported prior intensive outpatient treatment). Prior 12-step participation was limited; approximately half of the sample had attended fewer than two meetings (Mdn = 2.0) in the 90 days before admission. Average substance use severity of the sample and study outcomes at baseline are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Background and clinical characteristics of sample at intake (n = 195)

| Characteristic | M (SD) or n (%) |

| Background | |

| Male | 93 (48%) |

| African American | 30 (30%) |

| Hispanic | 15 (8%) |

| Single-parent household | 97 (50%) |

| Parent has high school diploma or less | 142 (73%) |

| Age, in years | 16.2 (1.1) |

| No. of felonies in previous 2 years | 0.5 (1.1) |

| Religiosity | |

| God consciousnessa | 6.2 (2.1) |

| Formal religious practicesa | 4.0 (2.4) |

| Substance use | |

| Percentage reporting prior residential treatment | 0.05 (0.09) |

| Readiness to changebb | 68.1 (15.4) |

| Twelve-step mediators | |

| General Alcoholics Anonymous Tools of Recovery | 63.5 (13.7) |

| Service to Others in Sobriety | 26.2 (10.5) |

| No. of meetings attended in last 90 days | 8.2 (15.0) |

| Substance-related outcomes | |

| Irresistibilityc | 20.6 (6.4) |

| Interferencec | 13.2 (6.1) |

| Psychosocial outcomes | |

| Children's Global Assessment Scale | 49.5 (2.7) |

| Exhibitionismd | 2.9 (1.7) |

| Entitlementd | 1.5 (1.1) |

| Vanityd | 1.5 (1.1) |

Subscale of the Religious Beliefs and Behaviors Questionnaire;

subscale of the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment;

subscale of the Adolescent–Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale;

subscale of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory.

Dependent t test statistics revealed that, after approximately 2 months of residential treatment, the sample overall demonstrated significantly increased 12-step participation and improved outcomes, with decreased NPI-vanity and NPI-entitlement approaching significance (p < .10; Table 2). Half of the sample (50%) had at least one positive toxicology screen for cannabinoids, and 17% had at least one positive toxicology screen for alcohol during treatment.

Association between lifetime religiosity and outcomes.

We first examined the direct effect of lifetime religiosity on each outcome separately, without 12-step mediators included in analytic models (ϕ.1 pathways presented in Table 4). Controlling for baseline covariates, formal religious practice was significantly associated with PPTS (F = 7.15, p < .01), A-OCDS irresistible craving symptoms (F = 3.27, p < .05), A-OCDS interfering craving symptoms (F = 2.38, p < .05), Children's Global Assessment Scale (F = 3.90, p < .05), and NPI-entitlement (F = 10.25, p < .001) but not NPI-exhibitionism (F = 1.60, p = 0.21) or NPI-vanity (F = 0.73, p = 0.39). In contrast, God consciousness was not associated with any study outcome. Because of the required significant association between predictor and outcome for mediational analysis, God consciousness was removed from mediated pathway analyses.

Table 4.

Path coefficients for effects of lifetime formal practices on12-step mediators, 12-step mediator, on outcomes, and mediated effects

| General Alcoholics Anonymous Tools of Recovery |

Service to Others in Sobriety |

12-step meetings |

|||||

| Variable | Path | Coefficient | [95% CI] | Coefficient | [95% CI] | Coefficient | [95% CI] |

| Substance-related outcomes | |||||||

| Percentage positive toxicology screens | ϕ.1 | −.01* | [−.05, −.00] | −.01* | [−.05, −.00] | −.01* | [−.05, −.00] |

| ϕ.2 | −.00 | [−.03, .02] | −.00 | [−.03, .01] | −.00 | [−.03, .02] | |

| α | .77* | [.33, .91] | .73** | [.19, .85] | .18 | [−.07, .31] | |

| β | −.01* | [−.11,-.00] | −.00 | [−.13, .06] | −.00 | [−.21,.04] | |

| αβ | .01* | [.00, .02] | −.00 | [−.01,.01] | .00 | [−.01,.02] | |

| Irresistibilitya | ϕ.1 | −.17* | [−.45,-.01] | −.17* | [−.45,-.01] | −.17* | [−.45, −.01] |

| ϕ.2 | −.01 | [−.38, .36] | −.02 | [−.39, .37] | −.01 | [−.38, .34] | |

| α | .77* | [.33, .91] | .73** | [.19, .85] | .18 | [−.07, .31] | |

| β | −.02 | [−.12, .06] | −.08* | [−.12,-.03] | .09 | [−.11,.22] | |

| αβ | −.04 | [−.05, .02] | .05* | [.01, .09] | .00 | [−.19, .25] | |

| Interferencea | ϕ.1 | −.24* | [−.49,-.01] | −.24* | [−.49,-.01] | −.24* | [−.49, −.01] |

| ϕ.1 | −.15 | [.42,. 17] | −.16 | [.44, .16] | −.16 | [.44, .16] | |

| α | .77* | [.33, .91] | .73** | [.19, .85] | .18 | [−.07, .31] | |

| β | −.02 | [−.10, .02] | −.03* | [−.11,-.01] | .10 | [−.12, .13] | |

| αβ | .01 | [−.02, .03] | .05** | [.01, .07] | .00 | [−.03, .06] | |

| Psychosocial outcomes | |||||||

| Children's Global Assessment Scale | ϕ.1 | .39* | [.01,.71] | .39* | [.01, .71) | .39* | [.01,.71] |

| ϕ.2 | .36 | [−.13, .65] | .32 | [−.15, .61] | .37 | [−.12, .66] | |

| α | .77* | [.33, .91] | .73** | [.19, .85] | .18 | [−.07, .31] | |

| β | .07 | [−.13, .06] | .15** | [.04, .24] | .01 | [−.03, .15] | |

| αβ | .01 | [−.01,. 06] | .01 | [−.05, .04] | .00 | [−.02, .16] | |

| Exhibitionismb | ϕ.1 | −.08 | [−.11,.13] | −.08 | [−.11,.13] | −.08 | [−.11,.13] |

| ϕ.1 | −.05 | [−.08, .15] | −.04 | [−.07, .15] | −.05 | [−.08, .15] | |

| α | .77* | [.33, .91] | .73** | [.19, .85] | .18 | [−.07, .31] | |

| β | .00 | [−.02, .03] | .00 | [−.02, .03] | .00 | [−.01,.04] | |

| αβ | .00 | [−.01,.01] | .01 | [−.00, .02] | .01 | [−.01,.02] | |

| Entitlementb | ϕ.1 | −.11* | [−.20, .05] | −.11* | [−.20, .05] | −.11* | [−.20, .05] |

| ϕ.1 | −.05 | [−.17, .01] | −.05 | [−.17, .01] | −.04 | [−.14, .02] | |

| α | .77* | [.33, .91] | .73** | [.19, .85] | .18 | [−.07, .31] | |

| β | −.01* | [−.04, −.00] | −.03** | [−.05,-.01] | .01 | [−.01,.09] | |

| αβ | .00 | [−.01,.01] | .01* | [.00, .02] | .00 | [−.01,.03] | |

| Vanityb | ϕ.1 | .05 | [−.01,.09] | .05 | [−.01,.09] | .05 | [−.01,.09] |

| ϕ.2 | .03 | [−.02, .09] | .04 | [−.03, .10] | .03 | [−.02, .09] | |

| α | .77* | [.33, .91] | .73** | [.19, .85] | .18 | [−.07, .31] | |

| β | −.02 | [−.03,. 11] | −.01 | [−.02, .03] | .00 | [−.01,.02] | |

| αβ | .00 | [−.01,.01] | .00 | [−.01,.09] | .00 | [−.01,.01] | |

Notes: Baseline covariates in all models included age, race, readiness for change, felony history, treatment history, parental marital status, parental education, and baseline assessment of 12-step mediators; ϕ.1 = lifetime formal practices effect on outcome, no 12-step mediators; ϕ.2 = lifetime formal practices effect on outcome with 12-step mediators; α = lifetime formal practices effect on 12-step mediator; β = 12-step mediator on outcome; αβ = mediated effect; NPI = Narcissistic Personality Inventory.

Subscale of the A-OCDS;

subscale of the NPI.

p <.05;

p < .01.

Association between lifetime religiosity and 12-step mediators.

Next, we examined the relationship between lifetime religiosity and three indices of 12-step participation during treatment. Controlling for baseline covariates and prior 12-step participation, God consciousness was not significantly associated with the SOS (F = 0.19, p = .66), meeting attendance (F = 0.28, p = 0.60), or the GAATOR (F = 2.30, p < .09). As indicated by the α pathways, formal religious practices were significantly associated with the GAATOR (F = 6.20, p < .05) and the SOS (F = 7.08, p < .01) but not meeting attendance (F = 0.27, p = 0.60).

Association between 12-step mediators and outcomes.

Regarding substance-related outcomes, the GAATOR was significantly associated with PPTS (r = -.12; β = -.01) and the A-OCDS interfering craving symptoms (r = -.10; β = -.02); small significant relationships were observed between the SOS and A-OCDS subscales (Table 4). Regarding psycho-social outcomes, the GAATOR was significantly correlated with the NPI-entitlement; the SOS was significantly correlated with the NPI-entitlement and the Children's Global Assessment Scale. Meeting attendance was not associated with any study outcome.

Mediated effect: Formal practices, 12-step mediators, and outcomes.

Path coefficients of formal practices’ effect on 12-step mediators (i.e., α pathways), 12-step mediators on outcomes (i.e., β pathways), and the mediated effect (i.e., aP pathways) are shown in Table 4. Significant αβ pathways emerged with substance-related outcomes; the GAATOR mediated the relationship between formal religious practices and PPTS (F = 3.98, p < .05), whereas the SOS mediated the relationship between formal religious practices and A-OCDS subscales (A-OCD irresistible craving symptoms: F = 2.36, p < .05; A-OCDS interfering craving symptoms: F = 2.68, p < .01). Last, the SOS mediated the relationship between formal practices and NPI-entitlement (F = 6.78, p < .05).

Discussion

This study examined the influence of two aspects of religiosity (formal religious practices and God consciousness) on during-treatment changes in 12-step involvement (work on the 12 steps, helping others, and 12-step meeting attendance) and how these related to both substance use (urine toxicology screens, changes in craving) and psychosocial (three dimensions of narcissism and a single rating of global functioning) outcomes. Greater lifetime religious practices, but not God consciousness, were found to be associated with better during-treatment substance-related outcomes and psychosocial outcomes. Also, greater lifetime religious practices were associated with increased step-work and with more AA/NA-related helping during treatment. In turn, greater step work was associated with fewer positive urine toxicology screens and lower narcissistic entitlement, whereas more AA/NA-related helping was associated with significant reductions in alcohol craving, narcissistic entitlement, and improved global functioning. Mediational analyses revealed that the superior substance-related and psychosocial treatment response experienced by those youth with greater lifetime religious practices could be explained, in part, by greater AA/NA-related helping and progress through the 12 steps during treatment.

In keeping with prior research showing protective effects for religious involvement against both the onset of SUDs and relapse, the current study found that severely substance-involved adolescents with greater lifetime religious practices at entry into residential treatment experience a better treatment response beyond the overall improvement of the sample (i.e., regression to the mean; Finney, 2008). Greater religious practices were significantly related to better during-treatment changes on all three substance-related outcomes as well as greater improvement in clinician-rated global functioning. Religious practices was also related to significant reductions in narcissism, but only on one of the three subscales examined: entitlement. Conceivably, greater religious practices may reduce a sense of entitlement by opening a door to greater openness, teachability, and humility—factors associated with many religious traditions. In contrast, it does not appear to make youth more amenable to adaptive changes in exhibitionism or vanity, although this may be less critical as, unlike entitlement, these narcissistic dimensions were not related to substance or psychosocial outcomes.

The benefit of this predisposition on treatment outcome was partially explained by greater adoption and implementation of 12-step prescribed behaviors; notably, AA/NA-related helping and greater progress through the 12 steps. Because most religious traditions discuss concepts and encourage practices similar to those espoused by 12-step programs (e.g., surrender, confession, forgiveness, making restitution, giving of oneself to help others), these former experiences may prepare individuals to assimilate more readily into 12-step–oriented treatments. Unclear, however, is whether the relatively better adoption of prescribed treatment practices among those with greater lifetime religious behavior is specific to 12-step activities or whether this represents a general tendency to conform to therapeutic suggestions, whatever they may be. It is conceivable, for instance, that as individuals enter treatment and the residual effects of substances diminish, those with more formal religious histories may experience greater cognitive dissonance as they become more conscious of the discrepancies between their religious values and convictions and their substance-induced behaviors (Miller and Rollnick, 1991). This, in turn, may lead to a desire to resolve the dissonance through abstinence facilitated by treatment compliance. Further research in non-12-step–oriented treatments is needed to investigate this possibility.

Noteworthy, too, was the effect of 12-step mediators on substance and psychosocial outcomes. Greater practicing of the 12 steps was associated with only two of the seven outcome variables: reductions in substance use and lower narcissistic entitlement. In contrast, AA/NA-related helping was associated with four of seven outcome variables: reductions in both craving subscales, improvement in global functioning, and, similar to the practice of the 12 steps, reduced narcissistic entitlement. Thus, AA/NA-related helping appears to exert a more pervasive beneficial effect, but both of these prominent 12-step activities appear to enhance salutary substance-related and characterological change, as well as improvements in global functioning.

These findings provide support for AA's proposition that maladaptive egocentrism can be attenuated through a focus on helping others (AA, 1976). There was also evidence of several mediated pathways between lifetime formal practices, 12-step mediators, and substance-related outcomes. Those with greater lifetime religious practices made more step work progress during treatment, which was associated with increased abstinence, and those with higher lifetime religious practices had higher AA/NA-related helping during treatment, which was associated with reductions in craving.

The study also found that during-treatment outcomes were not related to the constructs of God consciousness or 12-step meeting attendance. It is possible that God consciousness, characterized by more contemplative practices, influences behavior more strongly once individuals are stabilized and in early recovery rather than during treatment. Also, the controlled residential treatment setting where most youth were required to attend AA or went merely for the appeal of an offsite activity restricted the variability associated with AA attendance; hence, the results herein may not be representative of the relationships among these variables in community settings.

Limitations

Some limitations of our study merit attention. First, as noted, meeting attendance in our study may be inflated and thereby cloud its relationship with other variables. Although transportation and familial barriers can pose challenges for youth 12-step involvement, our study of youth 12-step participation across programmatic components nonetheless was made possible given that all youth had secured access to 12-step meetings. Second, although lifetime, intake, and discharge were the time points assessed, the majority of study outcomes and 12-step mediators were assessed concurrently at discharge. Consequently, although theory and other fully prospective research investigations can more strongly indicate the causal relationships between 12-step mediators and outcomes, the direction of causation between 12-step mediators and outcomes cannot be concluded. Furthermore, our tested models were not exhaustive, and other nonspecified variables could also account for observed relationships. In addition, co-variation among variables was not large, and it is possible that some behavioral assessments may have been constricted by the nature of the treatment setting. Finally, the majority of the sample was nonviolent first-time offenders court-referred to treatment. Although this is the most common referral source for youth entering SUD treatment, referrals that will increase with recent legislation changes (Courier, 2011), results may not generalize to populations where court-referred patients are not the norm.

Some strengths of our study were that gender and minority group status was well represented, increasing our ability to generalize to girls and black adolescent populations with substance dependence. Second, independent and dependent variables were assessed using multiple methods (i.e., bio-markers, semi-structured interviews, medical chart), multiple informants (i.e., clinician, rater-administered, and youth reports), and missing data rates were low (<10%). We used prospective biomarker assessment of substance use, medical chart information, and clinician report of adolescent AA/NA-related helping and global functioning to reduce the potential social desirability bias that is inherent in self-report assessment. Biomarkers were collected prospectively each week by clinical staff, who provided reliable assessments of substance use for all subjects on their return from an outside-facility outing (i.e., client pass, shuttle van to local meeting). Also, whereas unmeasured variables could exist that influence the processes of interest, the environment in which subjects were studied (e.g., 24-hour monitored care for 10 consecutive weeks) provided a natural incubator/laboratory to study youth behavior independent of familial or substance-using peer-group influences.

Conclusions

National epidemiological studies show that SUD begins during adolescence and, for many, has a prolonged and chronic course. These disorders and their related consequences confer a prodigious burden of disease and deep negative social and economic impacts. Despite evidence that the earlier effective treatment is initiated the shorter the duration and impact of SUD (Dennis et al., 2005), studies focusing on intervention effects and the factors that influence such effects are still comparatively rare among young people. The current study investigated the treatment response of a large sample of adolescents in relation to the influence of lifetime religious practices and tested whether any influence of lifetime religiosity on during-treatment outcomes could be explained by increases in 12-step participation. Our findings extend the evidence for the protective effects of religious behaviors to a better treatment response among adolescents and provide some preliminary support for the 12-step proposition that adopting 12-step practices, most notably a focus on helping others in recovery, may lead to better substance-related outcomes during treatment. Youth with low or no lifetime religious practices may assimilate less well into 12-step–oriented SUD treatment and may require additional 12-step facilitation, or a different approach, to enhance their treatment response.

Footnotes

Analyses and manuscript preparation were supported in part by a grant from the Templeton Foundation (to Maria E. Pagano), and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant K01AA015137 (to Maria E. Pagano) and Grants R01AA015526-04 and R21AA018185-01A2 (to John F. Kelly).

References

- Aarons GA, Brown SA, Coe MT, Myers MG, Garland AF, Ezzet-Lofstram R, Hough RL. Adolescent alcohol and drug abuse and health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:412–421. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholics Anonymous. Twelve steps and twelve traditions. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholics Anonymous. Alcoholics Anonymous: The story of how thousands of men and women have recovered from alcoholism. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholics Anonymous. Alcoholics Anonymous: The story of how thousands of men and women have recovered from alcoholism. 4th ed. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alford GS, Koehler RA, Leonard J. Alcoholics Anonymous-Narcotics Anonymous model inpatient treatment of chemically dependent adolescents: A 2-year outcome study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:118–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison P. Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham P. The Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale: A self-rated instrument for the quantification of thoughts about alcohol and drinking behavior. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19:92–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avants SK, Warburton LA, Margolin A. Spiritual and religious support in recovery from addiction among HIV-positive injection drug users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2001;33:39–45. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2001.10400467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Ribera JC. Further measures of the psychometric properties of the Children's Global Assessment Scale. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:821–824. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210069011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth J, Martin JE. Spiritual and religious factors in substance abuse, dependence and recovery. In: Koenig HG, editor. Handbook of religion and mental health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Ramo DE, Anderson KG. Long-term trajectories of adolescent recovery. In: Kelly JF, White WL, editors. Addiction recovery management: Theory, research and practice. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2011. pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carter TM. The effects of spiritual practices on recovery from substance abuse. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 1998;5:409–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.1998.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi FW, Kaskutas LA, Sterling S, Campbell CI, Weisner C. Twelve-Step affiliation and 3-year substance use outcomes among adolescents: Social support and religious service attendance as potential mediators. Addiction. 2009;104:927–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. Measure of religious background and behavior for use in behavior change research. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. Religiosity and responsiveness to alcoholism treatments. In: Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, editors. Project MATCH hypotheses: Results and causal chain analyses (Project MATCH Monograph Series, Vol. 8, pp. 166–175) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Courier F. Another Ohio view on criminal justice. Daily Jeffersonian. 2011, February 25 Retrieved from http://www.daily-jeff.com/news/article/4977581. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Toward the attainment of low-risk drinking goals: A 10-year progress report. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:1371–1378. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000139811.24455.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deas D, Roberts J, Randall C, Anton R. Adolescent Obsessive-Compulsive Drinking Scale: An assessment tool for problem drinking. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2001;93:92–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deas D, Roberts JS, Randall CL, Anton RF. Confirmatory analysis of the Adolescent Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (A-OCDS): A measure of ‘craving’ and problem drinking in adolescents/ young adults. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2002;94:879–887. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rosario PM, White RM. The Narcissistic Personality Inventory: Test-retest stability and internal consistency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39:1075–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, Funk R. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R, Foss MA. The duration and correlates of addiction and treatment careers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:S51–S62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Carbonari JP, Zweben A, Morrel T, Lee RE. Motivation hypothesis causal chain analysis. In: Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, editors. Project MATCH: Hypotheses, results, and causal chain analysis. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2001. pp. 206–223. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Schlundt D, Gemmell L. Readiness and stages of change in addiction treatment. American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13:103–119. doi: 10.1080/10550490490435777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Westra HA, Collins KA, Fung TS, Garry JKF. Stages of change in anxiety: Psychometric properties of the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA) scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:711–729. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Assessing readiness to change binge eating and compensatory behaviors. Eating Behaviors. 2003;4:305–314. doi: 10.1016/S1471-0153(03)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrborg J, Warborg Larsen F, Nielsen S, Byman J, Buhl Nielsen B, Gautrè-Delay F. The Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) and Global Assessment of Psychosocial Disability (GAPD) in clinical practice—substance and reliability as judged by intraclass correlations. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;9:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s007870070043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exline JJ, Baumeister RF, Bushman BJ, Campbell WK, Finkel EJ. Too proud to let go: Narcissistic entitlement as a barrier to forgiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:894–912. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW. Regression to the mean in substance use disorder treatment research. Addiction. 2008;103:42–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PM, Joe GW, Broome KM, Simpson DD, Brown BS. Recovery from opioid addiction in DATOS. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Increased rates of psychosocial disorders in youth. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1998;248:14–21. doi: 10.1007/s004060050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler RC, Rich CL, Young D. San Diego Suicide Study. II. Substance abuse in young cases. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:962–965. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800100056008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goggin K, Murray TS, Malcarne VL, Brown SA, Wallston KA. Do religious and control cognitions predict risky behavior? I. Development and validation of the Alcohol-related God Locus of Control Scale for Adolescents (AGLOC-A) Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2007;31:111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Anglin MD. Addiction treatment and recovery careers. In: Kelly JF, White WL, editors. Addiction recovery management: Theory, research and practice. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2011. pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K. Circles of recovery: Self-help organizations for addictions. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Moos RH. Can encouraging substance abuse patients to participate in self-help groups reduce demand for health care? A quasi-experimental study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:711–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Moos RH. Encouraging posttreatment self-help group involvement to reduce demand for continuing care services: Two-year clinical and utilization outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer Y, Blitz C, Burleson JA, Sussman J. The Teen Treatment Services Review (T-TSR) Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Subbaraman MS, Witbrodt J, Zemore SE. Effectiveness of Making Alcoholics Anonymous Easier: A group format 12-step facilitation approach. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF. Self-help for substance-use disorders: History, effectiveness, knowledge gaps, and research opportunities. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:639–663. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Brown SA, Abrantes A, Kahler CW, Myers MG. Social recovery model: An 8-year investigation of adolescent 12-step group involvement following inpatient treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:1468–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Dow SJ, Yeterian JD, Kahler CW. Can 12-step group participation strengthen and extend the benefits of adolescent addiction treatment? A prospective analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Moos R. Dropout from 12-step self-help groups: Prevalence, predictors, and counteracting treatment influences. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Myers MG, Brown SA. A multivariate process model of adolescent 12-step attendance and substance use outcome following inpatient treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:376–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Myers MG, Brown SA. Do adolescents affiliate with 12-step groups? A multivariate process model of effects. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:293–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Stout R, Zywiak W, Schneider R. A 3-year study of addiction mutual-help group participation following intensive outpatient treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1381–1392. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Yeterian JD. Mutual help groups. In: Donohue WO, Cunningham JR, editors. Evidence-based adjunctive treatments. Burlington, MA: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 61–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Stout RL, Magil M, Tonigan JS, Pagano M. Spirituality in recovery: A lagged mediational model of Alcoholics Anonymous principal theoretical mechanism of behavior change. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:454–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BP, Minami M. The Beech Hill Hospital/Outward Bound Adolescent Chemical Dependency Treatment Program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10:395–406. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90025-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, Johnson JA, Roman PM. Buprenorphine adoption in the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37:307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM. Clinical supervision, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention: A study of substance abuse treatment counselors in the Clinical Trials Network of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson MJ, Shepard DS, Zwick W, Stout R. Validity of health care utilization reporting systems [Abstract 195] Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21(Supplement S3):36A. [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Kabela-Cormier E, Petry NM. Changing network support for drinking: Network support project 2-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:229–242. doi: 10.1037/a0015252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Miranda R, Jr, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohsenow DJ, Gwaltney CJ. Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:106–114. doi: 10.1037/a0017513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Analysis of mediating variables in prevention and intervention research. In: Cazares A, Beatty LA, editors. Scientific methods in prevention research. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1994. pp. 127–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnaughy EA, DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. Stages of change in psychotherapy: A follow-up report. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1989;26:494–503. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ET, Neal DJ, Roberts LJ, Baer JS, Cressler SO, Metrik J, Marlatt GA. Test-retest reliability of alcohol measures: Is there a difference between internet-based assessment and traditional methods? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery HA, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Does Alcoholics Anonymous involvement predict treatment outcome? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1995;12:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)00018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Theory-based active ingredients of effective treatments for substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Labouvie E, McCrady BS, Kahler CW, Frey RM. Affiliation with Alcoholics Anonymous after treatment: A study of its therapeutic effects and mechanisms of action. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:768–777. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano ME, Carter RR, Johnson SM, Exline JJ. Addiction and "Generation Me": Comparison of narcissistic behaviors amongst American youth with and without substance disorders [Abstract 839] Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010a;34(Supplement S2):220A. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano ME, Krentzman AR, Onder CC, Baryak JL, Murphy JL, Zywiak WH, Stout RL. Service to others in sobriety (SOS) Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2010b;28:111–127. doi: 10.1080/07347321003656425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano ME, Zeltner BB, Jaber J, Post SG, Zywiak WH, Stout RL. Helping others and long-term sobriety: Who should I help to stay sober? Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2009a;27:38–50. doi: 10.1080/07347320802586726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano ME, Zemore SE, Onder CC, Stout RL. Predictors of initial AA-related helping: Findings from Project MATCH. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009b;70:117–125. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Plante TG, Sherman A, Stump JE. Religious faith and spirituality in substance abuse recovery: Determining the mental health benefits. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;19:347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physician Leadership on National Drug Policy. Adolescent substance abuse: A public health priority. Providence, RI: PLNDP National Project Office, Brown University, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies; 2002. Available at http://www.plndp.org/Physician_Leadership/Re-sources/adolescent.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Zemore S. Psychiatric severity and spirituality, helping, and participation in Alcoholics Anonymous during recovery. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:577–592. doi: 10.1081/ada-200032297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin R, Terry H. A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:890–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin RN, Hall CS. A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports. 1979;45:590. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey JM, Starling J, Wever C, Dossetor DR, Plapp JM. Inter-rater reliability of global assessment of functioning in a clinical setting. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 1995;36:787–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman PM, Blum TC. National Treatment Center Study (Summary 3) Athens, GA: University of Georgia; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. Convergence of narcissism measures from the perspective of general personality functioning. Assessment. 2008;15:364–374. doi: 10.1177/1073191108314278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S. A Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman DG, Ferguson GR. Two methods of assessing narcissism: Comparison of the Narcissism-Projective (N-P) and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1988;44:857–866. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198811)44:6<857::aid-jclp2270440605>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, O'Malley SS. Craving for alcohol: Findings from the clinic and the laboratory. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1999;34:223–230. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586Find-ings) Rockville, MD: Author; 2010. Available at http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k9NSDUH/2k9ResultsP.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Swindle RW, Peterson KA, Paradise MJ, Moos RH. Measuring substance abuse program treatment orientations: The Drug and Alcohol Program Treatment Inventory. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1995;7:61–78. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate analysis. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Brown SA. Substance dependence, family history of alcohol dependence and neuropsychological functioning in adolescence. Addiction. 2000;95:1043–1053. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95710436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Connors GJ, Miller WR. Alcoholics Anonymous Involvement (AAI) scale: Reliability and norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Vick D. Psychometric properties and stability of the General Alcoholics Anonymous Tools of Recovery (GAATOR 2.1) [Abstract 768] Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24(Supplement S5):134A. [Google Scholar]

- Walitzer KS, Dermen KH, Barrick C. Facilitating involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous during out-patient treatment: A randomized clinical trial. Addiction. 2009;104:391–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzelberg A, Humphreys K. Should patients’ religiosity influence clinicians’ referral to 12-step self-help groups? Evidence from a study of 3,018 male substance abuse patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:790–794. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Kaskutas LA. Helping, spirituality and Alcoholics Anonymous in recovery. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:383–391. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiak W, Larson MJ, Lawson C, Rubin A, Zwick W, Stout RL. Test-retest reliability of the health care data form [Abstract 769] Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23(Supplement S5):134A. [Google Scholar]