Abstract

A previously isolated T-even-type PP01 bacteriophage was used to detect its host cell, Escherichia coli O157:H7. The phage small outer capsid (SOC) protein was used as a platform to present a marker protein, green fluorescent protein (GFP), on the phage capsid. The DNA fragment around soc was amplified by PCR and sequenced. The gene alignment of soc and its upstream region was g56-soc.2-soc.1-soc, which is the same as that for T2 phage. GFP was introduced into the C- and N-terminal regions of SOC to produce recombinant phages PP01-GFP/SOC and PP01-SOC/GFP, respectively. Fusion of GFP to SOC did not change the host range of PP01. On the contrary, the binding affinity of the recombinant phages to the host cell increased. However, the stability of the recombinant phages in alkaline solution decreased. Adsorption of the GFP-labeled PP01 phages to the E. coli cell surface enabled visualization of cells under a fluorescence microscope. GFP-labeled PP01 phage was not only adsorbed on culturable E. coli cells but also on viable but nonculturable or pasteurized cells. The coexistence of insensitive E. coli K-12 (W3110) cells did not influence the specificity and affinity of GFP-labeled PP01 adsorption on E. coli O157:H7. After a 10-min incubation with GFP-labeled PP01 phage at a multiplicity of infection of 1,000 at 4°C, E. coli O157:H7 cells could be visualized by fluorescence microscopy. The GFP-labeled PP01 phage could be a rapid and sensitive tool for E. coli O157:H7 detection.

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) of serogroup O157:H7 has been found to cause bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome in humans. EHEC produces two toxins, namely Shiga toxins 1 and 2 (Stx1 and Stx2). The natural reservoirs of EHEC are cattle and other domestic animals (21, 22). Although the predominant mode of transmission to humans is via consumption of contaminated meat, infection via contaminated water has also been documented (1).

Rapid and sensitive detection of E. coli O157:H7 is essential for minimizing the outbreak of infection, for surveillance, and for sanitary supervision. Three methods, culturing, PCR analysis, and immunoassay, are available for the detection of E. coli O157:H7. These culture methods are laborious and expensive and require a minimum of 3 days to perform (4). PCR analysis of E. coli O157:H7 has often been aimed at detecting the genes for Stx1 and Stx2 (6). Although these assays may be useful for the examination of human or animal fecal samples, their usefulness for the examination of environmental samples is limited due to the widespread presence of these genes in nonpathogenic bacteria. Enzyme immunoassays have also been used for detecting E. coli O157 in enrichment cultures of food and environmental samples (2). Although sensitive, these assays are laborious and expensive and tend to yield positive results that cannot be confirmed by culturing (2).

E. coli O157:H7 enters a viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state after a lengthy exposure to oligotrophic fresh- and seawater at an ambient temperature. Although the role of VBNC cells in food or water safety is not fully known, VBNC E. coli O157:H7 was shown to occur widely in a natural freshwater environment in Tokyo, Japan (12). Direct viable cell counts of E. coli O157:H7, determined by acridine orange staining, remained essentially the same for 12 weeks at 25°C, whereas viable cell counts on tryptic soy agar plates decreased to undetectable levels within 12 weeks (7). Direct viable cell counts, however, can be applied only to axenic cultures and not to E. coli in natural environments, where mixed bacterial populations exist. Conventional culture methods also fail to detect VBNC E. coli O157:H7 in the natural environment.

A virulent phage (PP01), previously isolated from swine stool samples, was found to infect E. coli O157:H7 strains with a high specificity (15). In phages of the T2 family, the gene 38 product (Gp38), which is present at the tip of long tail fibers, is the determinant of host range (19). Analysis of deduced amino acid alignments of the tail fiber proteins revealed that the PP01 phage is related to the T2 phage. Moreover, the specific recognition of the E. coli O157:H7 OmpC protein by Gp38 determines PP01's host range (14). In this study, PP01 was used for the detection of E. coli O157:H7 in viable and VBNC states. One of the outer capsid proteins, named small outer capsid (SOC) protein, was fused with green fluorescent protein (GFP). Labeled recombinant PP01 phage provided a rapid and sensitive method for E. coli O157:H7 detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and bacteriophages.

The E. coli O157:H7 ATCC 43888 bacterial strain was used as the host for the phage. This strain does not produce either Stx1 or Stx2 because of the absence of genes for these toxins, but it possesses an envelope structure similar to that of EHEC O157:H7. The PP01 phage, isolated from swine stool and infectious to E. coli O157:H7 strains with high specificity and lytic activity (15), was employed for the construction of GFP-labeled bacteriophage.

In batch cultures, E. coli O157:H7 ATCC 43888 was cultured overnight in 2 ml of Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C with shaking (120 rpm). The optical density of the medium at 600 nm (OD600) was measured with a Klett spectrophotometer (Hitachi High-Technologies Corp.) to estimate the cell concentration. Bacteriophage PP01 infection at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 was performed at an OD600 of 0.1. For dilution and preservation of the phage, SM buffer (10 mM MgSO4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.01% gelatin, and 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]) was used. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used for the phage binding assay.

Sequencing of phage DNA.

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. PP01 phage DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and precipitated with ethanol. PP01 phage DNA was diluted with distilled water and used as a template for PCR. The oligonucleotide primers used for PCR and sequencing are listed in Table 2. The DNA fragment encoding PP01 SOC protein was amplified by use of the primer set of g56+ and mrh−. The primer set was designed based on the DNA sequence of T2 phage genome DNA. The PCR fragment was digested with PstI and XbaI and inserted into the PstI and XbaI sites of pUC118 to obtain pUC-SOC, which encodes the PP01 soc gene and its surrounding region. Sequencing of the cloned DNA was performed by using a Thermo Sequenase fluorescence-labeled primer cycle sequencing kit and a 7-deaza-dGTP kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The sequencer used was DSQ-2000L (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

TABLE 1.

Phages, E. coli strains, and plasmids used in this study

| Phage, strain, or plasmid | Properties or use |

|---|---|

| Phage | |

| PP01 | Virulent, E. coli O157:H7 specific |

| E. coli strains | |

| O157:H7 (ATCC43888) | Host cell for propagation of PP01 |

| XL-1 Blue | General cloning host |

| K-12 (W3110) | Nonsusceptible model bacteria |

| O157:H37 (CE237) | Host range assay |

| O157:H19 (A2) | Host range assay |

| O157:H7 (CR3) | Host range assay |

| BE | Host range assay |

| HfrH | Host range assay |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | Host range assay |

| Plasmids | |

| pUC118 | General cloning vector |

| pQB2 | Expression vector for GFP |

| pQB2′ | 720-bp PCR end-modified gfp cloned into KpnI site of pQB2 |

| pQB-GFP/SOC | Expression vector of GFP/SOC fusion protein |

| pUC-GFP/SOC1 | pUC118 inserted with 1.1-kb GFP/SOC from pQB-GFP/SOC |

| pUC-GFP/SOC | 0.5 kbp upstream of soc inserted into pUC-GFP/SOC1 |

| pUC-SOC (KpnI) | 1-kb soc, including its surrounding regions inserted into pUC118 |

| pUC-SOC/GFP | pUC-SOC (KpnI) with gfp inserted |

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used for PCR

| Primer | Sequence (5′ → 3′)a |

|---|---|

| g56+ | GCTCTAGAGAAGAAATCTTTAAACTTTATTATCTG |

| mrh2− | TCTAAGCTTGGTTTAATCCAACGATTTAACAT |

| mrh− | TGAAAGCTTCAAGCATCTTCTTCAGAACTT |

| socN+ | AACTGCAGGCATGGCTAGTACTCGCGGTTA |

| socN− | CATCTAGATCTCCTTTTATTTAAATTACATGAC |

| socC+ | GGGGTACCAGACTCTTCGGGAGTCCTTT |

| socC− | TTGGTACCCAGTTACTTTCCACAAATCTT |

| gfp+(Xba) | CTTCTAGATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTT |

| gfp+(Kpn) | GGGGTACCCATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTT |

| gfp− | GGGGTACCTTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCCA |

Restriction sites are shown in bold.

Construction of plasmid.

The gfp gene encoding GFP was amplified by PCR using the primer set of gfp+(Kpn) and gfp−, with plasmid pQB2 (11) as the template. KOD DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) was used for PCR. The PCR fragment was digested with KpnI and reinserted into the KpnI site of pQB2 to produce pQB2′, which lacks a stop codon for gfp. The DNA fragment encoding PP01 SOC and its downstream region (about 100 bp) was amplified by use of the primer set of socN+ and mrh2−, with the PP01 phage genome as a template. The PCR fragment was digested with PstI and HindIII and inserted into the PstI and HindIII sites of pQB2′ to produce pQB-GFP/SOC. The PCR fragment amplified using pQB-GFP/SOC as the template and the primer set of gfp+(XbaI) and mrh2− was digested with XbaI and HindIII and inserted into the XbaI and HindIII sites of pUC118 to produce pUC-GFP/SOC1. Then the PCR fragment amplified using the PP01 phage genome as the template and the primer set of g56+ and socN− was digested with XbaI and inserted into the XbaI site of pUC-GFP/SOC1 to produce pUC-GFP/SOC.

The DNA fragments encoding PP01 soc, its upstream region (about 200 bp), and its downstream region (about 100 bp) were amplified by use of the primer sets g56+-socC− and socC+-mrh−, respectively, with the PP01 phage genome as the template. The two PCR fragments were digested with XbaI-KpnI and KpnI-PstI, and the two fragments were inserted into the XbaI and PstI sites of pUC118 to produce pUC-SOC/KpnI. Then the gfp gene digested with KpnI from pQB2 was inserted into the KpnI site of pUC-SOC/KpnI to produce pUC-SOC/GFP.

Homologous recombination.

The protocol used to integrate gfp into the phage genome is outlined in Fig. 1. E. coli O157:H7 (ATCC 43888) was transformed with two plasmids, pUC-GFP/SOC and pUC-SOC/GFP, by electroporation. The transformant E. coli cells were incubated in LB medium supplemented with 50 mg of ampicillin per liter. When the OD600 reached 0.1, the PP01 phage was added at an MOI of 0.01. After 5 h of incubation, chloroform was added to lyse the cells and the culture was centrifuged to remove cell debris. The cell lysate was diluted with SM buffer to obtain a phage concentration of 104 PFU/ml. The diluted phage lysate was mixed with E. coli O157:H7 in 0.7% agar and overlaid on an LB plate. The recombinant phage was detected by plaque hybridization with a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probe. The plaques were transferred to a nylon membrane (Roche Diagnostics) and immersed in denaturing solution (0.5 M NaOH, 1.5 M NaCl) for 5 min, in neutralizing buffer (1.0 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5 M NaCl, pH 7.5) for 15 min, and in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0) for 10 min. Phage DNA was cross-linked on the membrane by UV radiation (1,200 J/cm2) and incubated in 2 mg of proteinase K solution per liter for 1 h at 37°C. The membrane was rinsed with distilled water and prehybridized in DIG-Easy-Hyb buffer (Roche Diagnostic) for 1 h at 55°C. The membrane was hybridized with the DIG-labeled gfp probe overnight at 55°C. The probe DNA was amplified by use of a PCR DIG-Probe-Synthesis kit (Roche Diagnostic), using pQB2 as the template and gfp+(KpnI) and gfp− as the primer set. The hybridized membrane was washed twice with 2× SSC containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 5 min at room temperature and once with 0.1× SSC containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 15 min at 68°C. Then the hybridized spot was detected by use of a DIG-Luminescent-Detection kit (Roche Diagnostic).

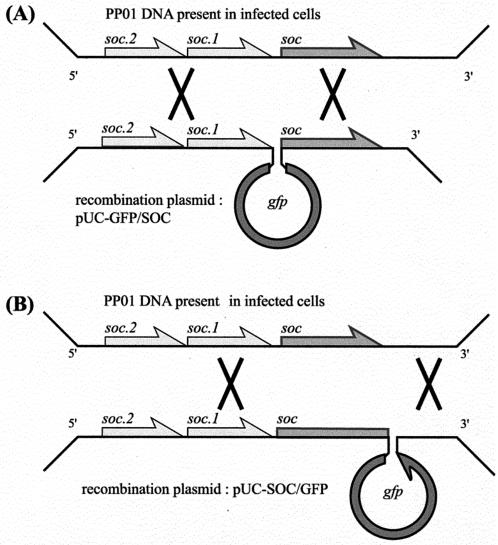

FIG. 1.

Outline of the homologous recombination process leading to insertion of gfp upstream (A) or downstream (B) of the major capsid protein gene soc. The multiplication signs indicate the recombination events (double crossover) between phage DNA (top) present in infected cells and pUC-GFP/SOC (A) or pUC-SOC/GFP (B).

Purification of the GFP-labeled phage.

A luminescent plaque was isolated and purified twice. Integration of gfp into the phage genome was reconfirmed by plaque hybridization. The isolated phage was added to the E. coli O157:H7 culture in 250 ml of LB broth at an MOI of 0.01 and incubated for 6 h. Chloroform (2.5 ml) was added to the culture, which was further incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Cell debris was separated by centrifugation (9,500 × g, 10 min, 4°C). The phage was precipitated by the addition of 25 g of polyethylene glycol 6000 and 10 g of NaCl, and the culture was allowed to stand overnight at 4°C. The phage was separated by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 60 min, 4°C) and resuspended in 10 ml of SM buffer. The phage solution was mixed with 20 ml of chloroform, allowed to stand for 6 h at 4°C, and centrifuged (10,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C) to remove cell debris. The phage was separated by cesium chloride (CsCl) density gradient (1.45, 1.5, and 1.7 g/ml) centrifugation (111,000 × g, 2 h, 4°C). CsCl was removed by dialysis in the SM buffer.

Phage adsorption assay.

E. coli O157:H7 cells in the logarithmic growth phase (107 CFU/ml) were preserved on ice until use. The cell culture (400 μl) was prewarmed at 25°C for 10 min and mixed with the same amount of phage solution (105 PFU/ml) in SM buffer. The mixture was incubated at 25°C. After infection, 110 μl of the mixture was sampled periodically, and the samples were centrifuged (174,000 × g, 1 min, 4°C). The phage titer of the supernatant was determined by plaque assay using E. coli O157:H7 (ATCC 43888), and the phage titer at time zero was defined as 100%.

Phage stability under alkaline conditions.

Phage solution (107 PFU/ml; 10 μl) was mixed with 990 μl of alkaline SM buffer (pH 10.6) and incubated at 37°C. The mixture was sampled periodically and diluted 1:100 with SM buffer (pH 7.5). The stability was estimated by comparing the phage titer in alkaline SM buffer with that in neutral SM buffer (pH 7.5).

Detection of E. coli O157:H7 by using GFP-labeled PP01 phage.

E. coli O157:H7 cell culture (107 CFU/ml) in the logarithmic growth phase was allowed to stand on ice until use. The cell culture was prewarmed at 25°C for 10 min and then mixed with the same amount of phage solution (5 × 109 PFU/ml). The mixture was allowed to stand at 25°C for 10 min, followed by centrifugation (17,400 × g for 1 min at 4°C), washing with PBS, and resuspension in PBS. Luminescent E. coli O157:H7, due to adsorbed GFP-labeled PP01 phage, was observed under an epifluorescence microscope (BX60; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a filter (U-MWIBA/GFP; Olympus). Photographs were taken with a digital still camera, with an exposure setting of 1/5 s for phase-contrast microscopy and 2 s for fluorescence microscopy.

Establishment of VBNC state.

An E. coli O157:H7 cell culture (107 CFU/ml; 30 ml) in the logarithmic growth phase was centrifuged (12,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C) and resuspended in the same amount of PBS. After 1 week of incubation at 4°C, cell viability was estimated by counting of colonies on LB plates.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper for soc will appear in the DDJB/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession number AY247798.

RESULTS

Construction of GFP-labeled PP01.

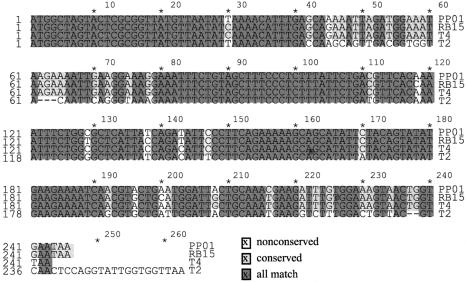

For amplification of the DNA fragment encoding the SOC protein of PP01 phage, two oligonucleotide primers, g56+ and mrh−, were constructed. The g56+ primer is complementary to the 3′ region of gene 56 from the T4 phage. g56 is well conserved among the T-even phages and is located upstream of soc. The mrh− primer was designed based on the sense alignment of the 3′ region of gene mrh encoded by the T4 phage. The PCR product of 1.9 kb was digested with PstI cloned into the same site of pUC118 and was used for sequencing. Two open reading frames, soc.1 and soc.2, were found between g56 and soc. The nucleotide sequence identities of soc genes among the T-even phages, PP01, RB15, T4, and T2, are shown in Fig. 2. The amino acid sequence identities between PP01 SOC and that of other T-even phages were 95.1% (RB15), 97.5% (T4), and 84.8% (T2). The numbers of amino acids making up the SOC proteins were 82 (PP01), 82 (RB15), 81 (T4), and 86 (T2).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequences of upstream and downstream soc regions from phages PP01, RB15, T4, and T2. Dashes indicate nucleotides that are deleted. Completely conserved nucleotides are shown in dark gray, and partially conserved regions are shown in light gray.

Although SOC is not an essential component for phage replication, it plays an important role in the stability of the phage capsid (8). To clarify the effect of N- and C-terminal fusion of GFP to SOC on phage stability, two recombinant PP01 phages, PP01-GFP/SOC and PP01-SOC/GFP, were constructed. PP01-GFP/SOC integrated GFP to the N terminus of SOC. In contrast, PP01-SOC/GFP integrated GFP to the C terminus of SOC.

To introduce gfp adjacent to soc, homologous recombination between the plasmid and the phage genome was conducted. The frequencies of recombination were approximately 0.3% for PP01-GFP/SOC and 0.5% for PP01-SOC/GFP. Several positive plaques, which emitted green fluorescence, were isolated from the agar plate and purified. Integration of gfp into the phage genome was confirmed by plaque hybridization and sequencing of the PCR-amplified DNA region around the soc-gfp and gfp-soc junctions (data not shown).

Characterization of GFP-labeled PP01.

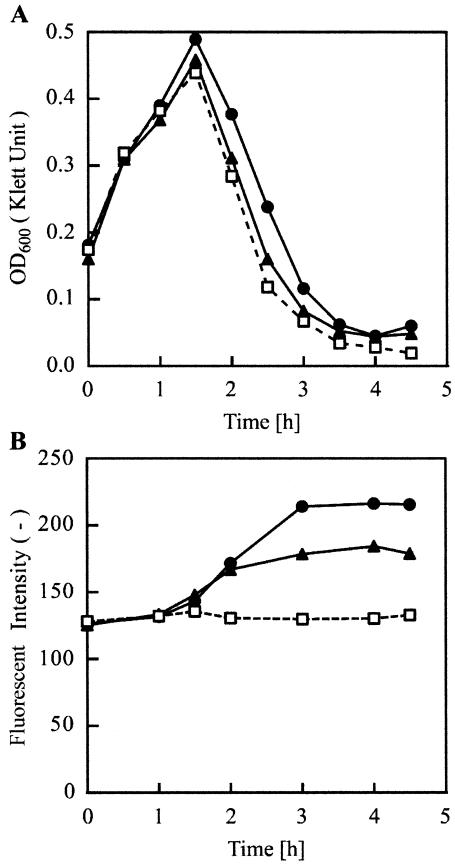

The turbidity and fluorescence changes of the E. coli O157:H7 culture after phage infection were measured (Fig. 3). Three phages, PP01-wt, PP01-GFP/SOC, and PP01-SOC/GFP, were added to the medium at time zero at an MOI of 0.1. Incubation was performed at 28°C to increase the fluorescence intensity. After a 1.5-h incubation of E. coli O157:H7 with one of the phages, a decrease in OD600 was observed. Since the LB medium contains self-luminous compounds, the initial fluorescence intensity of the culture was 125 (no dimension). The PP01-wt infection did not influence the fluorescence intensity of the culture. On the other hand, PP01-GFP/SOC and PP01-SOC/GFP infections increased the fluorescence intensity of the culture. Fluorescence intensity of the culture reached 220 (no dimension) 3 h after infection of PP01-GFP/SOC and remained almost constant. The maximum fluorescence intensity of the PP01-GFP/SOC culture was higher than that of PP01-SOC/GFP culture.

FIG. 3.

(A) E. coli O157:H7 lysis by PP01-wt (squares), PP01-GFP/SOC (circles), and PP01-SOC/GFP (triangles). (B) Phage-induced fluorescence of the culture. A 200-μl E. coli O157:H7 overnight culture was inoculated into 20 ml of LB medium at time zero and incubated at 28°C. When the OD600 of the culture reached 0.2, 200 μl of phage containing PBS was added at an MOI of 0.04.

PP01 formed relatively large (0.5 to 1.0 mm) and clear plaques on a cell lawn of E. coli O157:H7 but did not form any plaques on a lawn of E. coli K-12 strains and other related bacteria (16). The host range of the three phages was examined by using seven E. coli strains and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (Table 3). No difference in the host range was observed.

TABLE 3.

Host range of GFP-labeled PP01 phage

| Host serotype or strain | Susceptibility to phagea

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| wt-PP01 | PP01-GFP/SOC | PP01-SOC/GFP | |

| E. coli | |||

| K-12 (W3110) | − | − | − |

| O157:H37 (CE237) | − | − | − |

| O157:H19 (A2) | + | + | + |

| O157:H7 (CR3) | + | + | + |

| O157:H7 (ATCC 43888) | + | + | + |

| BE | − | − | − |

| HfrH | − | − | − |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | − | − | − |

+, susceptible; −, not susceptible.

To investigate the effect of GFP fusion to SOC on phage binding to the host cell, a phage adsorption assay was conducted. Free phage (Pfree, in PFU per milliliter) adsorption on the host cell (Bfree, in CFU per milliliter) surface proceeded by an initial reversible interaction, followed by a second irreversible interaction. The overall adsorption reaction and its kinetics can be described as follows.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

The ka value (milliliters per CFU per minute) is an adsorption rate constant. Under low-MOI (<0.01) conditions, Bfree can be assumed to be constant, that is B0, until lysis of the host cells. Therefore, integration of equation 2 is as follows.

|

(3) |

According to equation 3, the time course of the free phage concentration (Pfree) in the culture provided ka(B0) and ka, which represents phage adsorption affinity on the host cell. An E. coli O157:H7 cell culture (107 CFU/ml) in the early logarithmic growth phase was mixed with the same amount of one of the three phage solutions (105 PFU/ml) at 25°C. Pfree in the mixture was analyzed and plotted against the incubation time to estimate the ka(B0) and ka values (Table 4). The ka value of PP01-wt was smaller than those of PP01-GFP/SOC and PP01-SOC/GFP, indicating that the GFP fusion to SOC enhanced the phage binding affinity for the host cells.

TABLE 4.

Phage adsorption assay results

| Phage | ka (B0)O157 (min−1)a | ka (10−9 ml CFU−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|

| PP01-wt | 0.0555 ± 0.0032 | 1.58 |

| PP01-GFP/SOC | 0.0779 ± 0.0010 | 2.21 |

| PP01-SOC/GFP | 0.0846 ± 0.0012 | 2.40 |

(B0)O157, 3.52 × 107 ± 1.51 × 107 CFU/ml; results are means ± standard deviations.

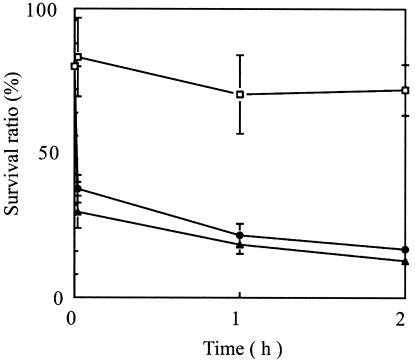

Since the T4 phage SOC deletion mutant has reduced stability under high-pH conditions (8), the effect of GFP fusion to SOC on phage stability was analyzed under high-pH conditions (Fig. 4). PP01-wt was relatively stable at a high pH. The viability of PP01-wt was approximately 70% during a 2-h incubation. A 2-min incubation of PP01-GFP/SOC and PP01-SOC/GFP at pH 10.6 reduced their viabilities to 47 ± 6% (PP01-GFP/SOC) and 37 ± 7% (PP01-SOC/GFP). However, a longer incubation period did not considerably reduce the phage viability. GFP-labeled phages PP01-GFP/SOC and PP01-SOC/GFP were more sensitive than PP01-wt at pH 10.6. GFP fusion to SOC reduced the phage stability in an alkaline solution.

FIG. 4.

Phage stability in alkaline solution. Three phages, PP01-wt (squares), PP01-GFP/SOC (circles), and PP01-SOC/GFP (triangles), were incubated in SM buffer (pH 10.6) at 37°C, without shaking. Survival ratios were estimated by comparing phage titers in the alkaline SM buffer with those in neutral SM buffer (pH 7.5).

Specific detection of E. coli O157:H7 by using GFP-labeled PP01.

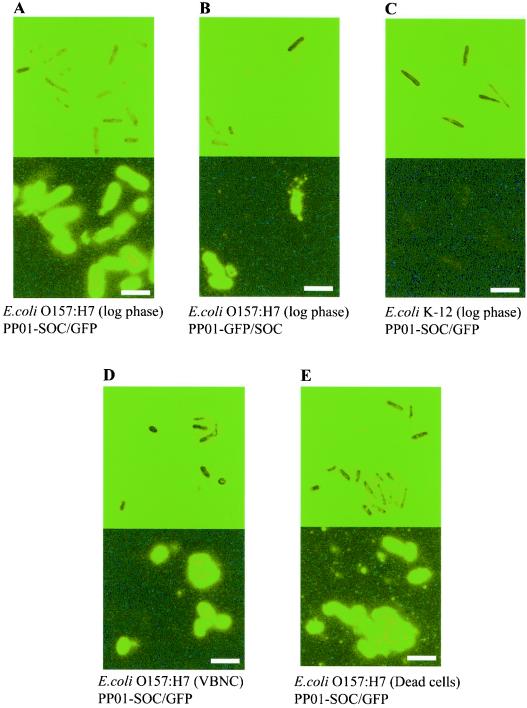

E. coli O157:H7 and E. coli K-12 (W3110) were incubated with PP01-wt, PP01-GFP/SOC, or PP01-SOC/GFP for 10 min at 25°C. After being washed with PBS, E. coli cells infected with the three phages were observed under an epifluorescence microscope (Fig. 5). E. coli O157:H7 infected with PP01-GFP/SOC and PP01-SOC/GFP generated fluorescence. On the other hand, E. coli K-12 (W3110) was not observed to be infected with the two phages. Fluorescence intensities of E. coli O157:H7 cells labeled with PP01-GFP/SOC and PP01-SOC/GFP were almost the same.

FIG. 5.

Optical microscope images (upper panels) and fluorescence microscope images (lower panels) of E. coli O157:H7 (A, B, D, and E) and E. coli K-12 (W3119) (C). The bacteria (107 CFU/ml) were incubated at 25°C for 10 min with PP01-SOC/GFP (A, C, D, and E) or PP01-GFP/SOC (B) (1010 PFU/ml). The E. coli cell states were logarithmic growth phase (A to C), VBNC (D), and dead (E). Scale bar, 2.5 μm.

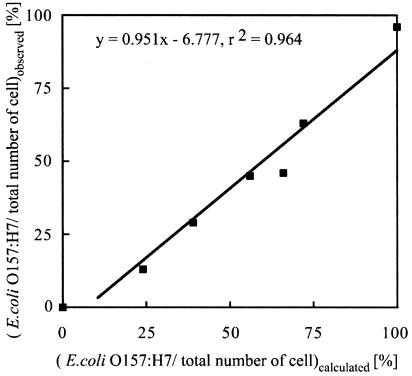

A cell mixture of E. coli O157:H7 and E. coli K-12 (W3110) cells was incubated with PP01-GFP/SOC for 10 min at 25°C. Cells were counted under optical and fluorescence microscopes. The count obtained by use of the optical microscope reflects the number of E. coli cells of strains O157:H7 and K-12 (W3110). In contrast, the count obtained by use of the fluorescence microscope reflects the number of E. coli O157:H7 cells. The percentage of E. coli O157:H7 cells in the E. coli mixture was plotted against the calculated percentage (Fig. 6). Both percentages showed a linear relationship (y = 0.951x - 6.777; r2 = 0.964), indicating that the fluorescence count of the cells reflects the number of E. coli O157:H7 cells in the E. coli mixture.

FIG. 6.

Correlation of E. coli O157:H7 percentage in cell mixture. A mixture of E. coli O157:H7 and E. coli K-12 (W3110) cells was incubated with PP01-GFP/SOC for 10 min at 25°C. The observed percentages were based on microscope counts and were plotted against calculated percentages from the initial concentrations of E. coli O157:H7 and K-12 cells.

Since most of the E. coli cells in different environments, such as wastewater, groundwater, and river water, are in the VBNC state, detection of VBNC E. coli O157:H7 by using PP01-SOC/GFP was investigated. The VBNC state was created by allowing E. coli O157:H7 to incubate in PBS buffer at 4°C for 1 week. After the 1-week incubation, the CFU count of cells decreased to 0.1. In contrast, the visible count of cells through the optical microscope did not change. The morphology of VBNC cells was relatively small and round. Ninety percent of the cells that did not form colonies were assumed to be in the VBNC state. Gentle pasteurization without damaging the cell surface was performed by incubating cells at 64°C for 5 min. The viability of E. coli cells was reduced to 0.6% after this pasteurization. The adsorption rate constant ka (in milliliters per CFU per min) of PP01-SOC/GFP for VBNC and pasteurized E. coli O157:H7 cells was the same, that is, 1.3 × 109 ml/CFU/min. The ka values for VBNC and pasteurized E. coli O157:H7 cells were lower than that (2.4 × 109 ml/CFU/min) for cells in the logarithmic growth phase. However, VBNC and pasteurized E. coli O157:H7 cells could be visualized by incubation with PP01-SOC/GFP (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

In the summer of 1996 in Japan, large outbreaks of EHEC O157:H7 infection occurred, particularly in Osaka City. After that, sporadic prevalent EHEC infections have been reported, and many school children and elderly people have been killed every year by this disease in Japan. In most of the cases, the serotype of EHEC was O157:H7. The conventional method of detection of E. coli O157:H7 is based on the cultivation of a sample on a cefixime-tellurite-sorbitol-MacConkey agar plate in combination with additional enzymological tests. These conventional methods are time consuming and require professional skill. The conversion of enteropathogenic bacteria to the VBNC state also makes it difficult to detect these cells in natural environments, such as river water and food. The development of rapid and reliable methods for E. coli O157:H7 detection is needed.

The PP01 phage used in this study was isolated from a swine stool sample. The finding that PP01 phage is a member of the T-even phage family enables us to apply genetic information on T-even phages to gene manipulation of PP01. T4 SOC is used as the platform for T4 phage display (10, 18). Since the high amino acid homology between PP01 SOC and T4 SOC was identified, PP01 SOC was also assumed to be available for PP01 phage display. Since the binding site of the SOC protein for the phage capsid protein is not located in the N or C terminus of SOC, foreign protein fusion to SOC does not disrupt the interaction between SOC and the phage capsid (10, 18). Gene alignments around soc for T-even phages are as follows: for T4, g56-g69-soc; for T2, g56-soc.2-soc.1-soc; and for RB15, g56-soc (17). The similarity of gene alignment around soc in PP01 and T2 also supported the finding that PP01 is a member of the T2 family. Even though PP01 is closely related to T2, the host cell specificities of these two phages are discriminative. The host range of PP01 is limited to E. coli serotype O157:H7 (16). Since the phage capsid is not involved in host cell recognition, modification of SOC did not change the host range of PP01. The adsorption rate constants, or ka values, of the recombinant phages, PP01-SOC/GFP and PP01-GFP/SOC, were larger than that of wild-type PP01. The number of SOC molecules present on the capsid was estimated to be 840 (9). Fusion of GFP to SOC enlarged the surface area of the capsid and may increase the collision probability for the recombinant phage and its host. A precise investigation of phage stabilities under various conditions, such as different temperatures and ionic strengths, was necessary for the preservation of the phage.

Infection of culturable E. coli O157:H7 cells by GFP-labeled phages increased the fluorescence intensity of the culture. The initial fluorescence was derived from the added phage and from auto-fluorescence of E. coli O157:H7 and the LB medium. Following a 1-h incubation with the recombinant phage, the fluorescence intensity of the culture increased gradually and reached a plateau at 3 h of incubation. The increase in fluorescence intensity reflected replication of recombinant progeny phage in cells. On the other hand, when the recombinant phages were added to VBNC or pasteurized E. coli O157:H7, no increase in fluorescence intensity was observed (data not shown). It is obvious that the host cell function is indispensable for phage replication in cells. Recombinant phages recognized both VBNC and pasteurized E. coli O157:H7 cells (Fig. 5). Based on these observations, discrimination of culturable cells from VBNC or dead cells may be possible by monitoring the change in the culture fluorescence intensity or by modifying the MOI. Under low-MOI conditions, the fluorescence intensity of phage-infected cells may be low. However, a 1-h incubation enables phage replication in the culturable cells, which are countable under a fluorescence microscope. On the other hand, the fluorescence intensity of VBNC or pasteurized E. coli O157:H7 cells infected by recombinant phages may remain constant. For the detection of both culturable and VBNC E. coli O157:H7 cells, a high MOI is desirable to enable strong visualization of the cells. Lysis from without (LO) is peculiar to the T4 phage (20). LO is lysis due to adsorption of a large number of T4 particles on the cell wall and occurs at MOIs of >20. However, LO of PP01 was not observed up to an MOI of 1,000.

Attempts to detect bacteria by use of specific phages have been reported previously (3, 5, 13, 23). However, the basic principles of these trials were based on the expression of fluorescence marker proteins, such as GFP and luciferase, in the host cells by integration of genes encoding the marker protein into the phage genome. Since the production of a marker protein depends on host cell activities, these methods fail to detect bacteria in the VBNC state, which is the most common state for bacteria in natural environments. GFP-labeled PP01 phage enables us to detect E. coli O157:H7 in both culturable and VBNC states. For the detection of both culturable and VBNC cells, a high MOI and a short incubation were used. On the other hand, for the detection of culturable cells alone, a low MOI and a long incubation time were needed. By changing the experimental conditions, we could distinguish culturable and VBNC cells.

The utilization of flow cytometry or image analysis might enhance the reliability of the method and shorten the detection time. For the application of this method for food enrichment or water samples, further studies, such as the assignment of a positive versus negative cutoff point, will be necessary.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by a grant (13450340) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackman, D. S., S. Marks, P. Mack, M. Caldwell, T. Root, and G. Birkhead. 1997. Swimming-associated haemorrhagic colitis due to Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection: evidence of prolonged contamination of a fresh water lake. Epidemiol. Infect. 119:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman, P. A., A. T. Cerdan Malo, C. A. Siddons, and M. A. Harkin. 1997. Use of a commercial enzyme immunoassay and confirmation system for detecting Escherichia coli O157 in bovine fecal samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2549-2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, J., and M. W. Griffiths. 1996. Salmonella detection in egg using Lux+ bacteriophages. J. Food Prot. 59:908-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dey, B. P., and C. P. Lattuada. 1998. Microbiology laboratory guidebook, 3rd ed., vol. 1. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C.

- 5.Funats, T., T. Taniyama, T. Tajima, H. Tadakuma, and H. Namiki. 2002. Rapid and sensitive detection method of a bacterium by using a GFP reporter phage. Microbiol. Immunol. 46:365-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gannon, V. P. J., R. K. King, and J. Y. Kim. 1992. Rapid and sensitive method for detection of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli in ground beef using the polymerase chain reaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3809-3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guodong, W., and D. Michael. 1998. Survival of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in water. J. Food Prot. 61:662-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishii, T., and M. Yanagida. 1977. The two dispensable structural proteins (soc and hoc) of the T4 phage capsid: their purification and properties, isolation and characterization of the defective mutants, and their binding with the defective heads in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 109:487-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki, K., B. L. Trus, P. T. Wingfield, N. Cheng, G. Campusano, V. B. Rao, and A. C. Steven. 2000. Molecular architecture of bacteriophage T4 capsid: vertex structure and bimodal binding of the stabilizing accessory protein, Soc. Virology 271:321-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang, J., L. Abu-shilbayeh, and B. R. Venigalla. 1997. Display of a PorA peptide from Neisseria meningitidis on the bacteriophage T4 capsid surface. Infect. Immun. 65:4770-4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimata, Y., M. Iwaki, R. L. Chun, and K. Kohno. 1997. A novel mutation which enhances the fluorescence of green fluorescent protein at high temperatures. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 232:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kogure, K., and E. Ikemoto. 1997. Wide occurrence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in natural fresh water. Nippon Saikingaku Zasshi 52:601-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loessner, M. J., C. E. D. Rees, G. S. A. B. Stewart, and S. Scherer. 1996. Construction of luciferase reporter bacteriophage A511::luxAB for rapid and sensitive detection of viable Listeria cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1133-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizoguchi, K., M. Morita, C. Y. Fischer, M. Yoichi, Y. Tanji, and H. Unno. 2003. Coevolution of bacteriophage PP01 and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in continuous culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:170-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morita, M., C. Y. Fischer, K. Mizoguchi, M. Yoichi, M. Oda, Y. Tanji, and H. Unno. 2002. Amino acid alternation in Gp38 of host range mutants of PP01 and evidence for their infection of an ompC null mutant of Escherichia coli O157:H7. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 216:243-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morita, M., Y. Tanji, K. Mizoguchi, T. Akitsu, N. Kijima, and H. Unno. 2002. Characterization of a virulent bacteriophage specific for Escherichia coli O157:H7 and analysis of its cellular receptor and two tail fiber genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 211:77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosig, G., J. Gewin, A. Luder, N. Colowick, and D. Vo. 2001. Two recombination-dependent DNA replication pathways of bacteriophage T4, and their roles in mutagenesis and horizontal gene transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8306-8311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren, Z., and L. W. Black. 1998. Phage T4 SOC and HOC display of biologically active, full-length proteins on the viral capsid. Gene 215:439-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riede, I., K. Drexler, H. Schwarz, and U. Henning. 1987. T-even-type bacteriophage use an adhesin for recognition of cellular receptors. J. Mol. Biol. 194:23-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarahovsky, Y. S., G. R. Ivanitsky, and A. A. Khusainov. 1994. Lysis of Escherichia coli cells induced by bacteriophage T4. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 122:195-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas, E. W., and C. Poppe. 2000. Construction of mini-Tn10luxABcam/Ptac-ATS and its use for developing a bacteriophage that transduces bioluminescence to Escherichia coli O157:H7. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 182:285-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vuddhakul, V., N. Patararunggrong, P. Pungrasamee, S. Jitsurong, T. Morigaki, N. Asai, and M. Nishibuchi. 2000. Isolation and characterization of Escherichia coli O157 from retail beef and bovine feces in Thailand. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 182:343-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.William, R. J., Jr., R. G. Barletta, R. Udani, J. Chan, G. Kalkut, G. Sonsne, T. Kieser, G. J. Sarkis, G. F. Hatfull, and B. R. Bloom. 1993. Rapid assessment of drug susceptibilities of Mycobacterium tuberculosis means of luciferase reporter phage. Science 260:819-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]