The C-terminal domain of FbiB, a bifunctional protein that is essential for the biosynthesis of cofactor F420 in M. tuberculosis, has been expressed, purified and crystallized. The crystals diffracted to 2.0 Å resolution and were suitable for structure determination.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, F420 biosynthesis, FbiB

Abstract

During cofactor F420 biosynthesis, the enzyme F420-γ-glutamyl ligase (FbiB) catalyzes the addition of γ-linked l-glutamate residues to form polyglutamylated F420 derivatives. In Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Rv3262 (FbiB) consists of two domains: an N-terminal domain from the F420 ligase superfamily and a C-terminal domain with sequence similarity to nitro-FMN reductase superfamily proteins. To characterize the role of the C-terminal domain of FbiB in polyglutamyl ligation, it has been purified and crystallized in an apo form. The crystals diffracted to 2.0 Å resolution using a synchrotron source and belonged to the tetragonal space group P41212 (or P43212), with unit-cell parameters a = b = 136.6, c = 101.7 Å, α = β = γ = 90°.

1. Introduction

The cofactor F420 is a flavin analogue that is essential for methanogenesis in archaea and is hypothesized to be important in the patho;genesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a ‘hydride carrier’ owing to its lower redox potential compared with NAD(P)+ (Boshoff & Barry, 2005 ▶). It has been suggested that under aerobic conditions this hydride carrier converts NO2 released by M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages to NO. As NO2 has been shown to be a more potent antimycobacterial agent, this might protect M. tuberculosis from nitrosative damage when it grows aerobically and causes active tuberculosis (Yu et al., 1999 ▶; Purwantini & Mukhopadhyay, 2009 ▶). The importance of this cofactor has increased in significance with the increasing number of coenzyme F420-dependent enzymatic reactions that have recently been identified in mycobacteria using comparative genomic methods (Selengut & Haft, 2010 ▶).

The open reading frame Rv3262 from M. tuberculosis encodes one of three enzymes that have been identified as being important in cofactor F420 biosynthesis in mycobacteria and is commonly termed FbiB (F 420 biosynthesis enzyme B; Choi et al., 2001 ▶, 2002 ▶). FbiB is a multi-domain protein derived from the F420 ligase superfamily (N-terminal domain; Pfam PF01996; Eker et al., 1990 ▶; Peschke et al., 1995 ▶; Graupner & White, 2003 ▶; Nakano et al., 2004 ▶) and the nitro-FMN reductase superfamily (C-terminal domain; Pfam PF00881; Hecht et al., 1995 ▶; de Oliveira et al., 2007 ▶) as indicated by sequence similarity. Following a series of biosynthetic reactions to form F420, FbiB catalyzes the addition of γ-linked l-glutamate residues to form polyglutamylated F420 derivatives (Li, Graupner et al., 2003 ▶). The length of the polyglutamate tail varies in different organisms. The majority of methanogenic and sulfate-reducing archaea predominantly have two glutamate residues, in which FbiB sequentially adds two γ-linked l-glutamate residues to F420-0 (Nocek et al., 2007 ▶). A γ-F420-2-α-l-glutamyl ligase (CofF) caps the polyglutamate tail with a terminal α-linked glutamate in several methanogenic archaea (Li, Xu et al., 2003 ▶).

In mycobacteria, the length of the polyglutamate tail varies by up to nine residues (Bair et al., 2001 ▶; Bashiri et al., 2008 ▶). The N-terminal domain of FbiB has 38% sequence identity to an archaeal F420-γ-glutamyl ligase for which the structure has been determined (PDB entry 2g9i; Nocek et al., 2007 ▶). The C-terminal domain of FbiB has 27% sequence identity to a nitroreductase from M. smegmatis (NfnB; PDB entry 2wzw; Manina et al., 2010 ▶), but it seems unlikely that its function is similar to that of NfnB, which inactivates antimycobacterial benzothiazinone drug molecules (Manina et al., 2010 ▶). It is reasonable instead to hypothesize that the C-terminal domain of FbiB facilitates elongation of the polyglutamate tail of cofactor F420 in mycobacterial species and its function has been annotated as such (NCBI CDD TIGR03553). Here, we describe the structural characterization of this domain of FbiB, including its expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning, expression and purification

The open reading frame (ORF) encoding Rv3262 was amplified from M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA. Primers were designed for directional cloning of inserts into the Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen). The primer sequences were Rv3262_F5 (5′-GGC AGC GGC GCG ATG ACC GCC GAA GCG CTC-3′) and Rv3262_R5 (5′-GAA AGC TGG GTG TTA TCA CTT CAG GAT CAG CAA-3′). The open reading frame encoding residues 245–448 of Rv3262 was cloned into an expression plasmid with an amino-terminal His6 tag, pDESTsmg (Goldstone et al., 2008 ▶). For the Gateway cloning, a nested PCR with two rounds of amplification was performed. The first round of PCR used the gene-specific primers to amplify the gene of interest. The second PCR utilized the product from the first round of PCR as a template and used generic primers to incorporate the attB sites required for the Gateway BP recombination reaction. The subsequent PCR product was cloned into the pDONR221 vector (Invitrogen) by recombination using BP Clonase (Invitrogen).

The recombination product was transformed into Escherichia coli Top10 cells and plated onto LB agar plates supplemented with 50 µg ml−1 kanamycin. Positive attL-flanked entry clones containing the gene of interest were screened by BsrGI restriction digest and sequencing. Positive clones were used in the subsequent recombination reaction with pDESTsmg and LR Clonase (Invitrogen) to generate an M. smegmatis expression plasmid. This construction resulted in the addition of a methionine at the first position of the amplified Rv3262-C gene and the addition of 32 extra residues at the N-terminus (MSHHHHHHLESPSTSLYKKAGFENLYFQGSGAM) of the recombinant protein. The LR recombination product was then transformed into E. coli Top10 cells and plated onto low-salt LB agar plates supplemented with 50 µg ml−1 hygromycin B for selection. Positive recombinant pDESTsmg plasmid clones were verified using BsrGI digestion.

The expression construct was electroporated into M. smegmatis strain mc24517 following a published protocol (Bashiri et al., 2010 ▶). Electrocompetent M. smegmatis mc24517 cells (40 µl) were mixed with 2 µl DNA in 0.2 cm cuvettes. A 260 µl volume of 10% glycerol was added to the mixture just before electroporation (electroporation parameters: R = 1000 Ω, Q = 25 µF and V = 2.5 kV; Bio-Rad Gene Pulser). After electroporation, the cells were immediately resuspended in 1 ml 7H9/ADC/Tween 80 solution (Difco and BBL Middlebrook). The cell suspension was incubated for 3 h at 310 K with shaking. The transformation was plated onto 7H10/ADC (Difco and BBL Middlebrook) agar plates supplemented with 50 µg ml−1 kanamycin and hygromycin B for selection.

The transformed His6-FbiB-C (FbiB C-terminal domain) construct was expressed from the M. smegmatis culture using autoinduction medium (Studier, 2005 ▶) supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80 and 50 µg ml−1 each of kanamycin and hygromycin B. Fresh singly transformed colonies were inoculated in the non-inducing medium MDG (25 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM NH4Cl, 5 mM Na2SO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1× trace metals, 0.5% glucose, 0.25% aspartate). The MDG cultures were incubated for 48–72 h at 310 K while shaking at 200 rev min−1. A 1:100 dilution of this culture was used to seed ZYM-5052 auto-induction medium (1% N-Z-amine AS, 0.5% yeast extract, 25 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM NH4Cl, 5 mM Na2SO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 1× trace metals, 0.5% glycerol, 0.05% glucose, 0.2% α-lactose; Studier, 2005 ▶). The expression cultures were grown for 4 d at 310 K while shaking at 200 rev min−1 (Bashiri et al., 2007 ▶). Cells were harvested by centrifugation (6800g, 20 min) and the cell pellets were kept at 253 K until use.

His6-FbiB-C cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol) containing Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Mini EDTA-free tablets (Roche) and passed twice through a cell disruptor at 17–18 kPa (Constant Systems Ltd). Insoluble matter was sedimented by centrifugation (17 000g, 40 min, 277 K). The soluble phase was filtered to 0.45 µm and loaded twice onto a HisTrap FF 5 ml nickel-affinity column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with wash buffer (lysis buffer plus 20 mM imidazole). The column was washed with at least ten column volumes of wash buffer before eluting the protein in a gradient of elution buffer (lysis buffer plus 500 mM imidazole). His6-FbiB-C protein was eluted at approximately 160 mM imidazole. Following SDS–PAGE analysis, fractions containing the purified His6-FbiB-C protein were pooled and dialyzed overnight into dialysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol) at 277 K.

The uncleaved His6-FbiB-C protein was concentrated using a 3 kDa molecular-weight cutoff spin concentrator (GE Healthcare) before being subjected to size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 75 10/300 column (GE Healthcare) for the final purification step. The eluted protein fractions were analysed by 12 or 15% SDS–PAGE. Each gel-filtration fraction was assessed for heterogeneity using dynamic light scattering (Wyatt DynaPro Titan, Wyatt Technology Corporation).

2.2. Crystallization

The initial screening of crystallization conditions for native FbiB-C was performed at 291 K using a Cartesian nanolitre dispensing robot (Genome Solutions) and a locally compiled crystallization screen (Moreland et al., 2005 ▶). The FbiB-C protein at a concentration of 15 mg ml−1 (in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl) was centrifuged at 16 000g for 15–30 min before setting up crystallization trays. Over 2–3 d, crystals were obtained from a variety of conditions. A grid screen using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion technique and a reservoir volume of 500 µl was performed around several promising conditions. After optimization of the best screening conditions, X-ray diffraction-quality crystals were grown in hanging drops in 24-well plates (Hampton Research) containing 1–2 µl protein solution at 15 mg ml−1 and 1–2 µl precipitant solution that were equilibrated against 500 µl precipitant solution (20–25% PEG 3350, 0.20–0.35 M Li2SO4). Paratone oil and mineral oil (in a 70:30 ratio) was used as a cryoprotectant before flash-cooling the crystals in liquid nitrogen.

2.3. Data collection

X-ray diffraction data sets were collected from single crystals on the Australian Synchrotron MX2 beamline at a wavelength of 0.976233 Å using an ADSC Quantum 315r CCD detector. The crystal-to-detector distance was set to 250 mm, the oscillation range was 1.0° and 195 images were collected. Data were collected using the Blu-Ice software (McPhillips et al., 2002 ▶), indexed and processed using XDS (Kabsch, 2010 ▶), reindexed using POINTLESS (Evans, 2006 ▶) and scaled with SCALA from the CCP4 program package (Evans, 2006 ▶; Winn et al., 2011 ▶).

3. Results and discussion

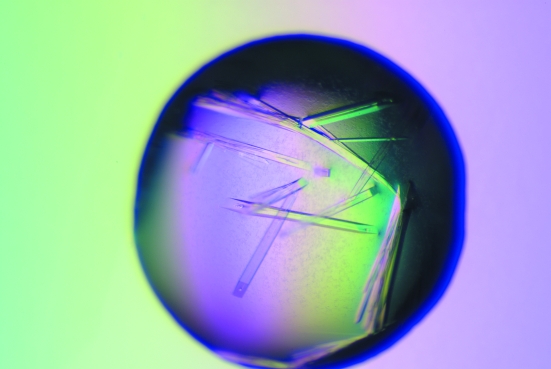

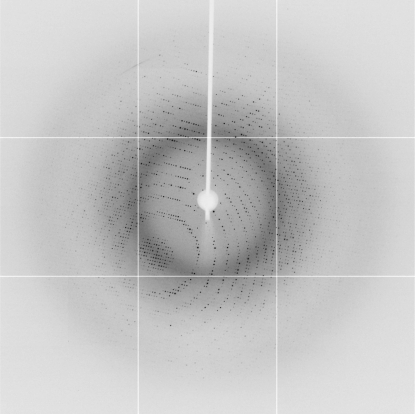

FbiB-C was expressed in M. smegmatis cells and purified by IMAC and size-exclusion chromatography. Both size-exclusion chromatography and DLS showed that the protein was dimeric in solution (data not shown). His6-FbiB-C protein eluted in a single peak was 99% pure based on SDS–PAGE and monodisperse in solution as indicated by DLS. Crystals grew readily by vapour diffusion in hanging-drop format to reach maximum dimensions of approximately 315 × 21 × 16 µm over several days. Larger crystals were obtained if the cover slides were deliberately poorly sealed to cause dehydration or if previous batches of crystals were seeded into fresh drops equilibrated overnight. Crystals of FbiB-C as shown in Fig. 1 ▶ diffracted to 2.0 Å resolution on the MX2 beamline at the Australian Synchrotron (Fig. 2 ▶). Data-collection statistics are given in Table 1 ▶. The crystals appeared to belong to the tetragonal crystal system, with unit-cell parameters a = b = 136.6, c = 101.7 Å, α = β = γ = 90° and with potential space groups suggested as P41212 or P43212 from analysis of the systematic absences. The Matthews coefficient of 2.69 Å3 Da−1 (Matthews, 1968 ▶) suggests the presence of four molecules per asymmetric unit with a solvent content of 54%. Self-rotation functions were calculated from the experimental data and from model coordinate systems (data not shown). The experimental self-rotation function is consistent with an asymmetric unit containing four molecules; specifically, two sets of dimers related by twofold NCS symmetry. Each dimer additionally displays internal twofold NCS symmetry.

Figure 1.

Crystals of FbiB-C (315 × 21 × 16 µm).

Figure 2.

A typical diffraction image obtained from FbiB-C crystals.

Table 1. Crystal and data-collection statistics for FbiB-C.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Space group | P41212 or P43212 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = b = 136.6, c = 101.7, α = β = γ = 90 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 19.97–2.00 (2.11–2.00) |

| Total reflections | 997618 |

| Unique reflections | 65279 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100.0) |

| Multiplicity | 15.3 (14.5) |

| Rmerge† (%) | 11.2 (56.8) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 19.6 (5.2) |

R

merge =

, where Ii(hkl) is the observed intensity and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the average intensity for multiple measurements.

, where Ii(hkl) is the observed intensity and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the average intensity for multiple measurements.

We have been unable to solve the structure by molecular replacement to date; no suitable model was available or could be identified owing to the low sequence identity to currently known structures of this family (<27%). Phasing efforts are currently under way and the structure will be reported elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken on the MX2 beamline at the Australian Synchrotron, Victoria, Australia. This research was supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the Foundation for Research, Science and Technology of New Zealand. AMR is the recipient of a PhD scholarship from the IPTA Academic Training Scheme from the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia and International Islamic University Malaysia.

References

- Bair, T. B., Isabelle, D. W. & Daniels, L. (2001). Arch. Microbiol. 176, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bashiri, G., Rehan, A. M., Greenwood, D. R., Dickson, J. M. J. & Baker, E. N. (2010). PLoS One, 5, e15803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bashiri, G., Squire, C. J., Baker, E. N. & Moreland, N. J. (2007). Protein Expr. Purif. 54, 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bashiri, G., Squire, C. J., Moreland, N. J. & Baker, E. N. (2008). J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17531–17541. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Boshoff, H. I. & Barry, C. E. (2005). Nature Rev. Microbiol. 3, 70–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.-P., Bair, T. B., Bae, Y.-M. & Daniels, L. (2001). J. Bacteriol. 183, 7058–7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.-P., Kendrick, N. & Daniels, L. (2002). J. Bacteriol. 184, 2420–2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Eker, A. P., Kooiman, P., Hessels, J. K. & Yasui, A. (1990). J. Biol. Chem. 265, 8009–8015. [PubMed]

- Evans, P. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Goldstone, R. M., Moreland, N. J., Bashiri, G., Baker, E. N. & Lott, J. S. (2008). Protein Expr. Purif. 57, 81–87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Graupner, M. & White, R. H. (2003). J. Bacteriol. 185, 4662–4665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hecht, H.-J., Erdmann, H., Park, H. J., Sprinzl, M. & Schmid, R. D. (1995). Nature Struct. Biol. 2, 1109–1114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li, H., Graupner, M., Xu, H. & White, R. H. (2003). Biochemistry, 42, 9771–9778. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li, H., Xu, H., Graham, D. E. & White, R. H. (2003). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 9785–9790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Manina, G. et al. (2010). Mol. Microbiol. 77, 1172–1185. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McPhillips, T. M., McPhillips, S. E., Chiu, H.-J., Cohen, A. E., Deacon, A. M., Ellis, P. J., Garman, E., Gonzalez, A., Sauter, N. K., Phizackerley, R. P., Soltis, S. M. & Kuhn, P. (2002). J. Synchrotron Rad. 9, 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moreland, N., Ashton, R., Baker, H. M., Ivanovic, I., Patterson, S., Arcus, V. L., Baker, E. N. & Lott, J. S. (2005). Acta Cryst. D61, 1378–1385. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nakano, T., Miyake, K., Endo, H., Dairi, T., Mizukami, T. & Katsumata, R. (2004). Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 68, 1345–1352. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nocek, B., Evdokimova, E., Proudfoot, M., Kudritska, M., Grochowski, L. L., White, R. H., Savchenko, A., Yakunin, A. F., Edwards, A. & Joachimiak, A. (2007). J. Mol. Biol. 372, 456–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, I. M. de, Henriques, J. A. & Bonatto, D. (2007). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 355, 919–925. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Peschke, U., Schmidt, H., Zhang, H.-Z. & Piepersberg, W. (1995). Mol. Microbiol. 16, 1137–1156. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Purwantini, E. & Mukhopadhyay, B. (2009). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 6333–6338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Selengut, J. D. & Haft, D. H. (2010). J. Bacteriol. 192, 5788–5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Studier, F. W. (2005). Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

- Yu, K., Mitchell, C., Xing, Y., Magliozzo, R. S., Bloom, B. R. & Chan, J. (1999). Tuber. Lung Dis. 79, 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed]