Abstract

The worldwide burden of cardiovascular disease is growing. In addition to lifestyle changes, pharmacologic agents that can modify cardiovascular disease processes have the potential to reduce cardiovascular events. Antihypertensive agents are widely used to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events partly beyond that of blood pressure-lowering. In particular, the angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), which antagonize the vasoconstrictive and proinflammatory/pro-proliferative effects of angiotensin II, have been shown to be cardio vascularly protective and well tolerated. Although the eight currently available ARBs are all indicated for the treatment of hypertension, they have partly different pharmacology, and their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties differ. ARB trials for reduction of cardiovascular risk can be broadly categorized into those in patients with/without hypertension and additional risk factors, in patients with evidence of cardiovascular disease, and in patients with severe cardiovascular disease, such as heart failure. These differences have led to their indications in different populations. For hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy, losartan was approved to have an indication for stroke prevention, while for most patients at high-risk for cardiovascular events, telmisartan is an appropriate therapy because it has a cardiovascular preventive indication. Other ARBs are indicated for narrowly defined high-risk patients, such as those with hypertension or heart failure. Although in one analysis a possible link between ARBs and increased risks of cancer has surfaced, several meta-analyses, using the most comprehensive data available, have found no link between any ARB, or the class as a whole, and cancer. Most recently, the US Food and Drug Administration completed a review of the potential risk of cancer and concluded that treatment with an ARB medication does not increase the risk of developing cancer. This review discusses the clinical evidence supporting the different indications for each of the ARBs and the outstanding safety of this drug class.

Keywords: angiotensin II receptor blocker, cardiovascular disease, cardiometabolic risk, cardiovascular prevention

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the major cause of death worldwide, and the number of global cardiovascular disease-related deaths is expected to increase from 16.7 million in 2002 to an estimated 23.3 million in 2030.1 Ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, the most common forms of cardiovascular disease, rank as the two leading causes of death worldwide, a trend that is driven by the prevalence rates in high-income and middle-income countries.1 It is only in low-income countries that human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome replaces cerebrovascular disease as the second leading cause of death, although ischemic heart disease still remains the leading cause even in these countries.1 These global rankings for cardiovascular disease are unlikely to change between now and 2030.1 Cardiovascular disease is a major burden in terms of the personal cost to patients resulting from cardiovascular disease morbidity-related loss of quality of life and the economic costs of the associated health care to society. For example, the estimated total costs of cardiovascular disease for 2010 in the US was $503.2 billion, of which $76.6 billion was due to hypertension alone.2 Similarly, cardiovascular disease is the main cause of mortality and morbidity in the European Union, costing the European Union economy €169 billion in 2003, of which around 62% was due to health care costs.3 The UK has particularly high total costs for cardiovascular disease (€36.5 billion), accounting for 22% of the total European Union costs.3 A separate study found that the total cardiovascular disease costs in the UK were £29.1 billion in 2004, with coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease accounting for 29% and 27% of the total costs, respectively.4 The UK spends approximately 18% of its total health care expenditure on cardiovascular disease, the highest proportion of any European Union country.4

There is a clear clinical and economic need to reduce the rate of cardiovascular disease, but this is challenging for a number of reasons, including the ever-increasing size of the elderly population and the growing burden of lifestyle-related diseases, such as obesity and diabetes mellitus, both known risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Although patients can do much to improve their cardiovascular disease risk profile by adopting nonpharmacologic interventions (eg, weight loss, dietary changes, smoking cessation), pharmacologic agents that can modify the disease processes involved in cardiovascular disease progression may play a crucial role in reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease. Hypertension is a well known risk factor for microvascular and macrovascular disease, and there is considerable evidence that lowering blood pressure reduces these risks.5 The renin-angiotensin system plays a crucial role in the development of hypertension and cardiovascular disease via the production of angiotensin II, which induces not only acute vasoconstriction by binding mainly to the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1) but also promotes vascular growth and proliferation, and endothelial dysfunction, leading to cardiovascular disease.6 Angiotensin II has multiple biological effects in addition to modulating blood pressure, including acting as a proinflammatory mediator at all stages of the cardiovascular and renal disease continua, which makes it an important target for intervention.7–9

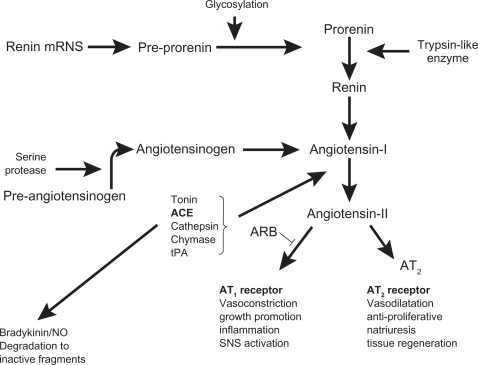

Blockade of the renin-angiotensin system is achieved by a number of agents that work by either inhibiting the effects of renin (direct renin inhibitors), conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II (angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors), or by blocking the binding of angiotensin II to the AT1 receptor (angiotensin II receptor blockers [ARBs], Figure 1). ACE inhibitors and ARBs now form part of the large arsenal of routinely used antihypertensive agents with cardioprotective effects beyond that of lowering blood pressure,10–13 and the first-in-class direct renin inhibitor, aliskiren, was approved for use in hypertension in the US and Europe in 2007. Direct renin inhibitors decrease plasma renin activity and inhibit the conversion of angiotensinogen to angiotensin I. Currently, there is limited evidence of any beyond blood pressure-lowering effects with the direct renin inhibitors, although a study has demonstrated that aliskiren is as effective as the ARB losartan in promoting left ventricular mass reduction in hypertensive patients.14 As beyond blood pressure-lowering evidence is lacking for the direct renin inhibitors, this class of agent will not be discussed further in this review, but the results of ongoing clinical trials for this drug class are awaited.15

Figure 1.

Scheme of the renin-angiotensin system.

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; NO, nitric oxide; SNS, sympathetic nervous system; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator; AT1, angiotensin II type 1 receptor; AT2, angiotensin II type 2 receptor.

The cardiovascular disease and renal pathophysiologic continua describe a chain of events, starting with hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and other risk factors (such as obesity and smoking), progressing through atherosclerosis, left ventricular hypertrophy, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, renal insufficiency and peripheral arterial insufficiency, and ultimately end-stage heart disease (left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure) and end-stage renal disease.7,16 This review examines the evidence that the ARBs are able to affect cardiovascular disease processes mediated by angiotensin II throughout the cardiovascular and renal disease continua. Large trials of ARBs with cardiovascular and renal endpoints were identified initially by reviewing recent guidelines, guideline updates, and other authoritative reviews. This was supplemented by targeted keyword searches on PubMed to identify relevant preclinical and clinical studies.

Effects of renin-angiotensin system blockade beyond lowering blood pressure

Blockade of the renin-angiotensin system reduces cardiovascular disease progression and end-organ damage not only by reducing blood pressure, but also by opposing the proinflammatory effects of angiotensin II.8 Both ARBs and ACE inhibitors have been investigated extensively for their effects on cardiovascular risk beyond blood pressure control alone in a very wide range of patients across the cardiovascular and renal disease continua.17–29

The beneficial effect of ACE inhibitors and ARBs results mainly from their blockade of the renin-angiotensin system, which not only directly reduces blood pressure, thus reducing the impact of this cardiovascular disease risk factor, but also reduces the proinflammatory effects of angiotensin II. Conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II is not completely blocked by ACE inhibitors because many other enzymatic pathways (eg, chymase, cathepsin, tonin, chymostatin-sensitive Ang II-generating enzyme, tissue-type plasminogen activator) exist, which can lead to the so-called “angiotensin escape phenomenon,” eg, a gradual return to pathologic levels of angiotensin II.30

Bradykinin degradation is also inhibited by ACE inhibitors, which can further enhance the vasodilatory effects of this mechanism of renin-angiotensin system blockade,31 but it is also thought to be involved in the pathology of the side effects (dry cough, angioedema).32 In addition to blocking the actions of angiotensin II that are mediated by the AT1 receptor, ARBs may also promote end-organ protection by leaving the AT2 receptor free to be activated by angiotensin II. AT2 receptor activation is thought to have the opposite effect of those mediated by the AT1 receptor, which are beneficial to the cardiovascular system and help protect target organs from damage.33

This potential to provide additional pleiotropic effects beyond those achieved by blood pressure-lowering alone has led to the use of renin-angiotensin system blockade in patients whose hypertension is compromised by the presence of additional cardiovascular disease risk factors, although it should be noted that there is debate over the degree to which these agents confer further benefits above those provided by simply lowering blood pressure.13,34,35 ARBs are often used in patients who are intolerant of ACE inhibitors due to the development of cough or angioedema,36–38 or in those who are at a high risk of developing either of these side effects. Patients over 60 years, females, those of east-Asian ethnicity and smokers are at increased risk of cough, and patients of African-American ethnicity, smokers, or those patients with a history of ACE inhibitor cough are at increased risk of angioedema.39 Although the available evidence suggests that ACE inhibitors and ARBs have similar blood pressure-lowering effects,40 ARBs are better tolerated than ACE inhibitors and other antihypertensive agents in both the short term and the long term.41 This is an important benefit, because hypertension is often asymptomatic, making long-term treatment adherence a challenge. However, the ARBs are not all equally effective. This review describes the intraclass differences in pharmacology and efficacy of the different ARBs, and how this translates into clinical benefit. Patients must be assessed thoroughly to determine their correct cardiovascular disease risk level so that the most appropriate ARB-based treatment can be selected.

ARBs: important differences in pharmacology and clinical efficacy

Pharmacology

There are eight ARBs currently on the market for hypertension and in different cardiovascular indications, ie, azilsartan, candesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan, telmisartan, and valsartan. The ARBs demonstrate considerable differences in their pharmacology, and these differences are likely to affect their clinical efficacy. Most ARBs share a common tetrazolo-biphenyl structure based on losartan.42,43 In contrast, telmisartan has a novel bisbenzimidazole structure, while eprosartan is a non-biphenyl non-tetrazole ARB.44 These differences in molecular structure lead to differences in the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of the ARBs, such as lipophilicity, volume of distribution, bioavailability, biotransformation, plasma half-life, receptor affinity, and residence time, elimination, and some specific pleiotropic effects (Table 1).45–47 For example, candesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, olmesartan, telmisartan, and the active metabolite of losartan are all noncompetitive (insurmountable) AT1 antagonists. They suppress the agonist response despite escalations in agonist concentration.45,48 Whether this translates into more effective protection from the effects of angiotensin II remains unknown. Of the ARBs, telmisartan has the highest affinity for the AT1 receptor and the longest receptor dissociation half-life,49 properties that are likely to be responsible for its long-lasting antihypertensive effects. Telmisartan also has the lowest half-maximal inhibitory concentration of any ARB, including the new ARB, azilsartan.50 Telmisartan is also the most lipophilic of the ARBs, which facilitates oral absorption and probably deep tissue and cellular penetration, and results in the highest volume of distribution of approximately 500 L (7 L/kg).46,51 Irbesartan demonstrates the highest oral bioavailability of the ARBs at 60%–80%, and eprosartan has the lowest.45 None of the ARBs interact with food, which makes oral administration very straightforward for this class of agents. The half-lives of the ARBs vary considerably, with valsartan at approximately seven hours and telmisartan having the longest, at approximately 24 hours.46,52,53 These half-life characteristics have implications for the duration of their therapeutic effects. Several of the ARBs, irbesartan and losartan, are metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP), and are therefore subject to potential drug-drug interactions with other drugs that alter CYP activity.54 Telmisartan can result in elevated serum digoxin in some patients.55 Clinically significant drug interactions are unlikely with either irbesartan or telmisartan,56 although CYP inducers (such as rifampicin and grapefruit juice) may interact significantly with losartan.56 In contrast with some of the ARBs, telmisartan is metabolized only via glucuronidation and almost entirely eliminated in the feces (>98%), so renal impairment is unlikely to affect the pharmacokinetics of this ARB.46

Table 1.

| Drug | tmax(h) | Bioavailability (%) | t½ (h) | Vd (L) | Interaction with food | Elimination (feces/urine) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Losartan | 1 (3–4)* | 33 | 2 (4–6)* | 34 (12)* | No | 60/35 |

| Valsartan | 2 | 23 | 7 | 17 | No | 83/13 |

| Irbesartan | 1–2 | 60–80 | 12–20 | 53–93 | No | 80/20 |

| Candesartan | 3–5 | 42 | 9–13 | 0.13 L/kg | No | 67/33 |

| Eprosartan | 2–6 | 13 | 5–7 | 308 | No | 90/10 |

| Telmisartan | 1 | 43 | 24 | 500 | No | >98% fecal |

| Olmesartan | 1.4–2.8 | 26† | 11.8–14.7 | 14.7–19.7 | No | 35%–49% urinary recovery rate‡ |

| Azilsartan | 1.5–3 | 60 | 11 | 16 | No | 55/42 |

Notes:

Values in parentheses are for EXP 3174, the active metabolite of losartan;

olmesartan medoxomil;

intravenous olmesartan.

Abbreviations: PK, pharmacokinetic; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; t½, terminal elimination half-life; tmax, time to maximum plasma concentration; Vd, volume of distribution.

A number of the ARBs exert multiple “pleiotropic” biological effects in addition to those mediated via the AT1 receptor that are worthy of special mention. However, the role these pleiotropic effects may play in cardiovascular disease prevention remains unclear. All ARBs appear to be able to penetrate the cell nucleus and partially activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), which in turn influences the expression of genes involved in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism;46,57 however, telmisartan is the only ARB shown to be able to activate PPARγ at therapeutic dosages.58 A range of metabolic effects has been studied, such as insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and blood glucose regulation, and, in general, telmisartan produces greater beneficial effects on glucose metabolism than the other ARBs.46 This additional activity of telmisartan may mean that this agent possibly affects the underlying biochemical features of the metabolic syndrome that increase the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease in high-risk populations.57 However, whether the PPARγ agonist effect could be clinically valuable in prevention of new-onset diabetes is still debated, because in the ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET®) there were no fewer cases of new-onset diabetes with telmisartan than with ramipril.28 Other ARB-specific pleiotropic effects have been reported. Azilsartan has been demonstrated to reduce plasminogen activator inhibitor type-I expression in the aortic walls of mice, which may limit the progression of atherosclerotic plaques that are at risk of rupture.58 Candesartan has been found to reduce redox-sensitive NF-κB-mediated renal inflammation independently of AT1 receptors, although not at therapeutic doses.59 Losartan inhibits urate transporter 1, thereby reducing serum uric acid levels.60 Serum uric acid appears to be an important, probably independent, risk factor for cardiovascular disease and renal disease, particularly in patients with hypertension.61 Evidence from the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint reduction in hypertension (LIFE) study demonstrated that the increase in serum uric acid over 4.8 years was reduced by losartan compared with atenolol and that this reduction appeared to explain 29% of the beneficial effect that losartan had on the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, and fatal or nonfatal stroke.62

Clinical efficacy of the ARBs

Studies in patients with hypertension

Pharmacokinetic factors, including bioavailability, volume of distribution, elimination half-life, and AT1 receptor interactions, all impact on the antihypertensive potency of the individual ARBs. A systematic review of studies that had used 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure measurements demonstrated significant differences between the ARBs studied in terms of 24-hour mean blood pressure reductions.63 However, these studies were mostly not direct comparisons, and also varied in doses employed and study designs. Direct comparisons are required to judge relative efficacy conclusively. For example, direct comparisons of olmesartan with other ARBs, several of them conducted since the review,63 have found it to give blood pressure reductions superior to losartan,64–66 and either superior,64,65 similar,67 or inferior68 to valsartan, while two small studies have found it to be inferior to telmisartan.69,70 Azilsartan, at its maximal dose, produced superior 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure reductions compared with olmesartan and valsartan at their maximal approved doses.71,72 All of the ARBs are associated with favorable tolerability profiles, which probably explains the enhanced persistence and treatment adherence with these agents compared with all other classes of antihypertensive agents.41,73

Primary and secondary prevention trials have demonstrated that, in addition to reducing blood pressure effectively, many of the ARBs reduce both cardiovascular disease progression and events, although few direct comparative studies of the ARBs in cardiovascular disease prevention exist. However, when considering trial data, it is crucial to consider the characteristics of the study population. ARB cardiovascular and renal outcome trials have been conducted in patients at different stages in the cardiovascular and renal disease continua: hypertension and early-stage cardiovascular disease; with or without hypertension but at an increased cardiovascular risk due to a prior cardiovascular disease event or the presence of diabetes; and with cardiovascular disease, left ventricular dysfunction, and heart failure.

The next section of this review presents data from the most important clinical trials that have studied ARBs in patients at the various stages along the cardiovascular and renal disease continua (Table 2).19–22,24,27–29,74–85,88–96 Although there are similarities between these patient populations, there are also important differences, particularly those with heart failure, who tend to be older and who usually present with several comorbidities.86 Therefore, we will consider the evidence for the different groups separately.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and findings from selected outcomes trials of angiotensin II receptor blockers in patients at different stages of the cardiovascular and renal disease continua17–20,22,25–27,67–78

| Study | Patient characteristics | Treatments | Primary outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies in patients with hypertension and other complications | |||

| LIFE22 | Patients aged 55–80 years, with essential hypertension and LVH; n = 9193 | Losartan- or atenolol-based antihypertensive regimen; mean follow-up: 4.8 years | Significant reduction in composite endpoint of CV death, MI, or stroke with losartan-based regimen versus atenolol-based regimen |

| VALUE74 | Patients aged ≥50 years, with hypertension and a high risk of cardiac events based on the presence qualifying risk factors; n = 15,313 | Valsartan- or amlodipine-based antihypertensive regimen; mean follow-up: 4.2 years | No significant difference between treatments for the composite endpoint of cardiac morbidity and mortality. Amlodipine demonstrated superior efficacy compared with valsartan on the incidence of MI, which was most likely a BP-related effect |

| The Kyoto Heart Study75 | Patients aged ≥20 years, with uncontrolled hypertension and high CV risks; n = 3031 | Valsartan- or non-ARB-based antihypertensive regimen; median follow-up 3.27 years | Significant reduction in the composite endpoint of fatal and nonfatal CV events with the valsartan-based regimen versus the non-ARB-based regimen. Relatively soft endpoints driving the results and the open-label design have been a source of criticism |

| IRMA220 | Patients aged 30–70 years, with T2DM, hypertension and persistent microalbuminuria; n = 590 | Irbesartan or placebo on a background of antihypertensive treatment; median follow-up 2.0 years | Significant reduction in the primary endpoint of a UAE rate >200 μg/min that was 30% higher than baseline with irbesartan vs placebo. Findings confirmed in a substudy using 24-hour ABPM61 |

| RENAAL21 | Patients aged 31–70 years, with T2DM, hypertension and diabetic nephropathy; n = 1513 | Losartan or placebo on a background of antihypertensive treatment; mean follow-up 3.4 years | Significant reduction in the primary composite endpoint of a doubling of the baseline serum creatinine concentration, the development of ESRD, or all-cause mortality with losartan vs placebo (−16%) |

| IDNT19 | Patients aged 30–70 years, with T2DM, hypertension and diabetic nephropathy; n = 1715 | Irbesartan or amlodipine or placebo on a background of antihypertensive treatment; mean follow-up 2.6 years | Significant reduction in the primary composite endpoint of a doubling of the baseline serum creatinine concentration, the development of ESRD or all-cause mortality with irbesartan vs amlodipine (−23%) and with irbesartan vs placebo (−20%) |

| DETAIL®24 | Patients aged 35–80 years, with T2DM, mild to moderate hypertension and early nephropathy; n = 250 | Telmisartan or enalapril on a background of antihypertensive treatment; mean/median follow-up not available | Equivalent reduction in the primary endpoint of the change in the GFR from baseline during 5 years of treatment with telmisartan vs enalapril |

| AMADEO®27 | Patients aged 21–80 years, with T2DM, hypertension, or on antihypertensive drugs and overt nephropathy; n = 860 | Telmisartan or losartan on a background of antihypertensive treatment mean follow-up 0.89 years | Significant reduction in the primary endpoint of the difference in the urinary albumin to creatinine ratio from baseline to week 52 with telmisartan vs losartan despite similar BP reductions in the 2 groups |

| VIVALDI®77 | Patients aged 30–80 years, with T2DM, hypertension and overt nephropathy; n = 885 | Telmisartan or valsartan on a background of antihypertensive treatment mean/median follow-up not available | Equivalent reductions in the primary endpoint of the change from baseline in the 24-hour proteinuria after 12 months for telmisartan and valsartan. Greater renoprotection was seen in those patients with better BP control |

| Studies in high-risk patients with a broad range of risk factors | |||

| ONTARGET28 | High-risk patients aged ≥55 years, with coronary, peripheral, or cerebrovascular disease or diabetes with end-organ damage; n = 25,620 | Telmisartan-, ramipril- or telmisartan plus ramipril-based antihypertensive regimens; median follow-up 4.7 years | Telmisartan was equivalent to ramipril for the primary composite endpoint of CV death, MI, stroke, or hospitalization due to HF, but it was associated with less angioedema and better treatment adherence. The combination was associated with more adverse events without an increase in efficacy |

| TRANSCEND29 | High-risk patients aged ≥55 years, with coronary, peripheral, or cerebrovascular disease or diabetes with end-organ damage, and intolerant to ACE inhibitors; n = 5926 | Telmisartan regimen or placebo-based regimen (on a background of other antihypertensive agents); median follow-up 4.7 years | Equivalent reduction in the primary composite endpoint of CV death, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for HF with telmisartan vs placebo. Significant reduction in the secondary composite endpoint of CV death, MI, or stroke with telmisartan (13%; HR 0.87) vs placebo (14.8%) |

| ROADMAP93 | High-risk patients with type 2 diabetes and at least one additional cardiovascular risk factor, but no evidence of renal dysfunction; n = 4447 | Olmesartan regimen or placebo-based regimen (on a background of other antihypertensive agents); median follow-up 3.2 years | No significant difference on the primary (time to first onset of microalbuminuria) or secondary (composite of CV complications or death from CV causes). A significant excess of CV mortality seen in the olmesartan arm |

| Studies in high-risk patients with HF | |||

| VALIANT78 | Patients aged ≥18 years, with HF or left ventricular systolic dysfunction, or both, and prior MI; n = 14,703 | Valsartan monotherapy, captopril monotherapy, or valsartan plus captopril on a background of antihypertensive treatment; median follow-up 2.1 years | Equivalent efficacy for the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality for all three groups. The valsartan plus captopril group had the most drug-related adverse events |

| Val-HEFT79 | Patients aged ≥18 years, with chronic HF and left ventricular systolic dysfunction; n = 5010 | Valsartan monotherapy or placebo on a background of antihypertensive treatment, which was ACE inhibitors in 93% of patients; mean follow-up 1.9 years | Equivalent efficacy for the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality for the 2 groups. Significant reduction in the composite endpoint of mortality and morbidity with the valsartan-based regimen vs the placebo-based regimen, and this was driven by a 24% reduction in the rate of adjudicated hospitalizations for worsening HF |

| OPTIMAAL80 | Patients aged ≥50 years, with HF or left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and acute MI; n = 5477 | Losartan monotherapy or captopril monotherapy on a background of antihypertensive treatment; mean follow-up 2.7 years | Trend for superior efficacy in the captopril group compared with the losartan group for the endpoint of all-cause mortality. Losartan was significantly better tolerated than captopril, being associated with significantly fewer discontinuations |

| ELITE II81 | Patients aged ≥60 years, with HF and left ventricular systolic dysfunction; n = 3152 | Losartan monotherapy or captopril monotherapy on a background of antihypertensive treatment; median follow-up 1.5 years | Equivalent efficacy for the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality for the 2 groups. Losartan was significantly better tolerated than captopril, being associated with significantly fewer discontinuations |

| HEAAL82 | Patients aged ≥18 years, with HF, left ventricular systolic dysfunction and known intolerance to ACE inhibitors; n = 3846 | Losartan 50 mg/day vs 150 mg/day on a background of antihypertensive treatment; median follow-up 4.7 years | Significant reduction in the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality and hospital admission for HF with the higher-dose losartan group compared with the lower-dose losartan group. There was no significant difference in the rate of treatment discontinuation between the doses |

| CHARM-Overall83 | Patients aged ≥18 years, with HF with/without left ventricular systolic dysfunction; n = 7601 | Candesartan or placebo on a background of antihypertensive treatment; median follow-up 3.1 years | Significant reduction in the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality with candesartan vs placebo |

| CHARM-Preserved84 | Patients aged ≥18 years, with HF with preserved left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction >40%); n = 3023 | Candesartan or placebo on a background of antihypertensive treatment; median follow-up 3.0 years | Nonsignificant reduction in the primary composite endpoint of CV death or hospital admission for HF with candesartan vs placebo; the reduction was driven by significantly fewer candesartan-treated patients being hospitalized or HF |

| I-PRESERVE85 | Patients aged ≥60 years, with HF with preserved left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction ≥45%); n = 4128 | Irbesartan or placebo on a background of antihypertensive treatment; mean follow-up 4.1 years | No significant difference in the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality and hospitalization for a CV event with irbesartan vs placebo |

Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; AMADEO®, A trial to compare telMisartan 40 mg titrated to 80 mg versus losArtan 50 mg titrated to 100 mg in hypertensive type 2 DiabEtic patients with Overt nephropathy; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; CHARM, Candesartan in Heart failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity; CV, cardiovascular; DETAIL®, Diabetics Exposed to Telmisartan And enalaprIL; ELITE-II, Evaluation of Losartan In The Elderly-II; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HEAAL, Effects of high-dose versus low-dose losartan on clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; IDNT, Irbesartan Type II Diabetic Nephropathy Trial; I-PRESERVE, Irbesartan in HF with preserved EF; IRMA-2, IRbesartan in patients with type 2 diabetes and MicroAlbuminuria; LIFE, Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MI, myocardial infarction; OPTIMAAL, OPtimal Therapy In Myocardial infarction with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan; RENAAL, Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; UAE, urinary albumin excretion; Val-HEFT, Valsartan in Heart Failure Trial; VALIANT, VALsartan in Acute myocardial iNfarcTion; VALUE, Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation; VIVALDI®, A trial to inVestigate the efficacy of telmIsartan versus VALsartan in hypertensive type 2 DIabetic patients with overt nephropathy.

Studies in hypertensive patients and other risk factors

There have been a number of studies of cardiovascular disease and renal outcomes with ARBs conducted in patients at the relatively early stages of the cardiovascular disease continuum, ie, patients with hypertension and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as type 2 diabetes with renal disease. The LIFE study randomized 9193 patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy to receive either once-daily losartan-based or atenolol-based antihypertensive therapy for at least four years.22 The losartan-based regimen demonstrated a significant benefit over the atenolol-based regimen with respect to the primary composite outcome (cardiovascular mortality, stroke, and myocardial infarction, relative risk [RR] 0.87, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.77–0.98; P = 0.021). The primary endpoint of the LIFE trial was mostly driven by the clinically important and statistically significant reduction in stroke morbidity/mortality.22 Unfortunately, atenolol, the comparator in the LIFE study, has subsequently been shown to be no better than placebo in reducing cardiovascular mortality and myocardial infarction,87 but β-blockers have been proven to reduce stroke morbidity and mortality in placebo-controlled trials. Consequently, the LIFE study resulted in an indication of losartan for the prevention of stroke morbidity/mortality in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy.

The Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) study recruited 15,313 patients with hypertension and a high risk of cardiovascular events based on a number of qualifying risk factors, such as age ≥50 years, verified diabetes mellitus, current smoker, high total cholesterol levels, and the presence of any of a number of other qualifying cardiovascular diseases.74 The study randomized the patients to receive antihypertensive therapy based on either valsartan or amlodipine.74 Both regimens reduced blood pressure, but the antihypertensive effects of the amlodipine-based regimen were more pronounced, particularly in the early stages, ie, months 1–6 of treatment.74 In terms of the primary composite endpoint of cardiac mortality and morbidity, there was no significant difference between the two regimens (hazard ratio [HR] 1.04, 95% CI 0.94–1.15; P = 0.49).74 Amlodipine demonstrated superior efficacy in the early stage, ie, the first three months, of the trial compared with valsartan on the incidence of nonfatal myocardial infarction and stroke, which was most likely a blood pressure-related effect, while valsartan was better in preventing both heart failure and new-onset diabetes at the later stage, ie, 36 months and beyond, of the trial.74

The addition of valsartan to conventional treatment prevented more cardiovascular events (angina pectoris, heart failure, dissecting aneurysm of the aorta, stroke/transient ischemic attack) than supplementary conventional treatment in the Jikei Heart Study.88 More recently, the Kyoto Heart Study demonstrated that valsartan added to conventional antihypertensive therapy prevented more cardiovascular events than the conventional non-ARB regimen in a patient population similar to that of the VALUE study.75 Valsartan was associated with significantly fewer primary composite endpoints (fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events) than the non-ARB regimen (HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.42–0.72; P = 0.00001). It is important to note that although the inclusion criteria were similar for the two studies (uncontrolled hypertension and additional risk factors), the hypertensive patients (n = 3031) included in the Kyoto Heart Study had a lower incidence of existing cardiovascular disease than the VALUE trial population and their in-trial blood pressure reductions were greater. This study was of particular value in terms of determining the beyond blood pressure-lowering effects of valsartan, because the blood pressure reductions were closely matched in the two arms throughout the study.75 However, the open-label design of the study has been criticized, particularly in light of the fact that the superior efficacy of valsartan was strongly influenced by the relatively soft endpoints of angina and transient ischemic attacks, which were included in the composite endpoint.

Several studies have shown that ARBs are renoprotective in patients with symptoms of early and overt nephropathy, reducing the risk of further proteinuria and progression to end-stage renal disease. For example, the IRbesartan in patients with type 2 diabetes and MicroAlbuminuria (IRMA2) study demonstrated that the addition of irbesartan to a background of other antihypertensive agents delayed the development of diabetic nephropathy in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes and persistent microalbuminuria.20 In this study, the blood pressure-lowering effects of irbesartan were similar to those of the placebo (ie, the background antihypertensive therapy), supporting the theory that the renal effects of irbesartan were independent of blood pressure-lowering. Similarly, losartan added to existing antihypertensive therapies was found to have beneficial renal effects in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy in the Reduction of Endpoints in Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) study.21 The losartan-based regimen was associated with a 16% reduction in the primary composite endpoint of a doubling of the baseline serum creatinine concentration, the development of end-stage renal disease or all-cause mortality.21 In the Irbesartan in Diabetic Nephropathy (IDNT) study, which compared irbesartan with amlodipine and placebo, all added to existing antihypertensive therapies, in patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy, irbesartan significantly reduced the risk of the primary composite endpoint of a doubling of the baseline serum creatinine concentration, end-stage renal disease or all-cause mortality compared with amlodipine (−23%) and placebo (−20%).19

Cerebroprotective effects of ARBs are mostly related to their blood pressure-lowering effects. In patients with isolated systolic hypertension, candesartan significantly decreased incidence of stroke in a subgroup of patients involved in the Study on COgnition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE) trial.89 In the LIFE trial,90 the incidence of stroke was significantly lower with losartan than with atenolol in the broad spectrum of at-risk patients involved, ie, those with isolated systolic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or atrial fibrillation. In patients who had already suffered from stroke, candesartan, initiated on the first day, significantly reduced the incidence of vascular event rates in the Evaluation of Acute Candesartan CilEexetil therapy in Stroke Survivors (ACCESS) trial.91 Eprosartan was more effective than nitrendipine in the MOrbidity and mortality after Stroke – Eprosartan compared with nitrendipine for Secondary prevention (MOSES) trial. The effect of telmisartan started soon after an ischemic stroke was not significantly different from that of placebo in lowering the rate of recurrent stroke and major cardiovascular events in the Prevention Regimen For Effectively avoiding Second Strokes (PRoFESS®) trial,92 most probably because the duration of the trial (2.5 years) was too short, and because of the counterbalancing effect of other antihypertensives reducing blood pressure.

A direct head-to-head comparison of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB in patients with type 2 diabetes, mild to moderate hypertension, and early nephropathy, the Diabetics Exposed to Telmisartan And enalaprIL (DETAIL®) study,24 demonstrated equivalent efficacy for telmisartan and enalapril in terms of the primary endpoint of change in glomerular filtration rate. In contrast, telmisartan reduced proteinuria more than losartan in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes with overt nephropathy in A trial to compare telMisartan 40 mg titrated to 80 mg versus losArtan 50 mg titrated to 100 mg in hypertensive type 2 DiabEtic patients with Overt nephropathy (AMADEO®),27 despite similar blood pressure reductions. Telmisartan reduced proteinuria to an equivalent degree compared with valsartan in the inVestIgate the efficacy of telmIsartan versus VALsartan in hypertensive type 2 DIabetic patients with overt nephropathy (VIVALDI®) study.77 The AMADEO and VIVALDI studies used broadly similar designs. Therefore, the results may reflect differences in antiproteinuric effect between telmisartan, losartan, and valsartan. However, methodologic differences and variations between patient-related parameters (eg, use of adjuvant antihypertensive agents, ethnic diversity) may also explain why telmisartan was superior to losartan and equivalent to valsartan.46

Studies in high-risk patients with a broad range of additional risk factors

Patients with normal blood pressure (normotensive or well controlled on antihypertensive therapy) but who still have a high cardiovascular disease risk because of a prior cardiovascular event or concomitant diabetes who do not yet have heart failure, form a substantial population. There have been three studies of cardiovascular disease outcomes with ARBs conducted in patients at this stage of the cardiovascular disease continuum, and both were with telmisartan. The first study, ONTARGET, randomized 25,620 patients at high cardiovascular risk with vascular disease (coronary, peripheral or cerebrovascular disease) or diabetes with end-organ damage, to receive telmisartan, the reference standard ACE inhibitor ramipril, or a combination of the two agents.28 This trial demonstrated that, in terms of the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or hospitalization due to heart failure, telmisartan was noninferior to ramipril (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.94–1.09), but it was better tolerated. Because blood pressure was equally controlled by the two agents, the results of the ONTARGET trial suggest that telmisartan, like ramipril, prevents cardiovascular events beyond that provided by blood pressure-lowering alone.28 The combination of the two agents was no more effective in terms of the primary composite outcome, but it was associated with a higher rate of adverse events (eg, hypotension, acute dialysis) than the single agents alone. The results of this trial suggest that dual renin-angiotensin system blockade with combinations of ACE inhibitors and ARBs offers no additional benefits in this specific patient population, while telmisartan was similarly effective as the established standard of ramipril.

The second study, the Telmisartan Randomized AssessmeNt Study in ACE-I iNtolerant subjects with cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND®) trial, ran in parallel with the ONTARGET trial and recruited patients who were not able to tolerate ACE inhibitors.29 This trial randomized 5926 patients with cardiovascular disease or diabetes with end-organ damage, many of whom were receiving existing therapies (best standard of care), to receive either telmisartan or placebo. The primary composite outcome was the same as that for the ONTARGET trial. The addition of telmisartan to the existing treatment regimen resulted in lower blood pressure throughout the study. In terms of the primary composite outcome, telmisartan did not demonstrate significant effects compared with the best standard of care group (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.81–1.05; P = 0.216). In contrast, the secondary composite endpoint, which, like the primary composite endpoint in the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study18 did not include new-onset heart failure, did demonstrate the beneficial effect of telmisartan (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.76–1.00; P = 0.048 unadjusted).29 Also, the TRANSCEND trial demonstrated that significantly fewer patients were hospitalized for cardiovascular reasons in the telmisartan group than in the placebo group.

A third study, the Randomized Olmesartan and Diabetes Microalbuminuria Prevention (ROADMAP) trial, was a placebo-controlled study in patients without hypertension but with diabetes and at least one additional cardiovascular risk factor.93 The primary endpoint was the time to first onset of microalbuminuria, which after adjusting for blood pressure differences, was nonsignificant. There was also no significant difference in the secondary endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular complications or death from cardiovascular causes (HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.75–1.33; P = 0.99). However, deaths from cardiovascular causes were significantly higher with olmesartan (n = 15, 0.7%) than with placebo (n = 3, 0.1%; HR 4.94, 95% CI 1.43–17.06; P = 0.01). Although the cause of this excess mortality is unknown, a similar excess cardiovascular mortality with olmesartan was also seen in the Olmesartan Reducing Incidence of End Stage Renal Disease in Diabetic Nephropathy Trial (ORIENT).94 Therefore, olmesartan should be used with caution in patients at high risk due to the presence of cardiovascular risk factors.

Studies in high-risk patients with heart failure

There have been a number of studies of ARBs in patients at the end of the cardiovascular disease continuum, ie, in patients with heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction. The VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarction Trial (VALIANT)78 trial demonstrated equivalent efficacy for the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality for valsartan and captopril in patients with heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction after a recent myocardial infarction. VALIANT also showed little advantage in implementing dual renin-angiotensin system blockade by administering both valsartan and captopril. The Valsartan HEart Failure Trial (Val-HEFT) demonstrated that the addition of valsartan to an existing antihypertensive treatment, which was mainly an ACE inhibitor, reduced hospital admission for worsening heart failure but not mortality,79 again suggesting that, in general, dual renin-angiotensin system blockade confers additional therapeutic efficacy only in a subgroup of patients not receiving β-blockers.93

In contrast with VALIANT, an earlier study with losartan 50 mg/day and captopril 3 × 50 mg/day, the Evaluation of Losartan In The Elderly II (ELITE II) trial81 found equivalent efficacy for the endpoint of all-cause mortality and a tolerability advantage for losartan. The OPtimal Therapy in Myocardial Infarction with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (OPTIMAAL) trial80 demonstrated a trend (P = 0.069) of a higher efficacy of captopril over losartan at the same doses used in the ELITE II trial (3 × 50 mg/day and 50 mg/day, respectively) for the same endpoint, although losartan was again significantly better tolerated than captopril. However, a more recent study, the Effects of high-dose versus low-dose losartan on clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure (HEAAL) study,82 found that a three-times higher dose of losartan (150 mg/day) was more effective than the lower dose of 50 mg/day, suggesting that the dose of losartan was probably too low in both the OPTIMAAL and ELITE II trials.

The Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) trial83 demonstrated superior efficacy for candesartan over standard antihypertensive treatment in terms of deaths and hospital admissions, although the CHARM-Preserved trial84 demonstrated no benefits of the addition of candesartan in heart failure patients who had a preserved ejection fraction. Similarly, the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with preserved EF (I-PRESERVE) trial85 found no benefit of the addition of irbesartan to standard antihypertensive treatment in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. In patients with heart failure on hemodialysis, telmisartan added to background ACE inhibitor therapy reduced all-cause mortality (HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.32–0.82) compared with best usual care, as well as hospital admissions for congestive heart failure and cardiovascular deaths.96

ARB-based combination therapy

The usual approach taken in the management of hypertension is to initiate treatment with a single agent, which is then titrated to its full dose. However, because most hypertensive patients require combination therapy, guidelines worldwide now recommend initial combination therapy (including renin-angiotensin system inhibitors) in patients most likely not at goal, with monotherapy, and calcium channel blockers and diuretics being the preferred combination partners.11,13

There is evidence to support the use of low-dose combination therapy to increase the blood pressure-lowering efficacy of the component drugs while reducing the incidence of adverse events.97,98 The reduction in blood pressure achieved with drugs used in combination is usually additive.97–99 A number of ARB-based combination therapies are recommended based on the results of randomized efficacy trials. In the US, seven of the currently available eight ARBs are available in single-pill combinations with the thiazide diuretic, hydrochlorothiazide,10,12,13 and three ARBs (valsartan, olmesartan, and telmisartan) as single-pill combinations with amlodipine. Among the antihypertensive drug classes, ACE inhibitors and ARBs are recommended for the largest variety of compelling indications, which for the ARBs include reduction of cardiovascular morbidity, heart failure, post-myocardial infarction, diabetic renal disease, proteinuria/microalbuminuria, left ventricular hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation, metabolic syndrome, and ACE inhibitor-induced cough.12,13 Around 66% of the recommended dual antihypertensive combinations are based on ACE inhibitors and ARBs.12

There are few data on the reduction of cardiovascular endpoints beyond blood pressure-lowering with combinations of antihypertensive agents. In particular, there is currently no evidence for ARB-based combination therapy, although the blood pressure-lowering effects of ARBs in combination with thiazide diuretics and calcium channel blockers have been shown to be additive.100–105 An additional benefit of using an ARB, such as valsartan, olmesartan, or telmisartan, with the calcium channel blocker amlodipine is that the incidence of amlodipine-related edema is reduced.102–105 In contrast with the ARBs, there are fewer data for ACE inhibitor-based combinations. The Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial investigated whether the ACE inhibitor benazepril 40 mg combined with the calcium channel blocker amlodipine 10 mg would reduce cardiovascular disease events more effectively than benazepril 40 mg in combination with the diuretic hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg.106,107 Treatment with the benazepril-amlodipine combination was associated with a 2.2% absolute risk reduction and a 19.6% relative risk reduction (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.72–0.90; P < 0.001) in the primary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, hospitalization for angina, resuscitation after sudden cardiac arrest, and coronary revascularization.107 A significant risk reduction associated with the benazepril–amlodipine combination was also found for the secondary endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.67–0.92; P = 0.002), and for renal disease progression (HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.41–0.65; P < 0.0001).106,107

Safety of ARBs

Many large clinical trials have shown favorable tolerability of ARBs, characterizing these drugs as the safest in cardiovascular medicine. Some seven years ago, results of a published meta-analysis108 suggested that ARBs may increase the risk of myocardial infarction. This meta-analysis was later vehemently debated/contradicted,109–112 and convincingly refuted by many more comprehensive and updated meta-analyses, taking into account all major international, randomized trials using ARBs compared with another active drug or conventional therapy (placebo) which reported information on rates of myocardial infarction. These analyses found no significant differences in fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction among treatment with ARBs, placebo, or active treatment, even in those trials in which ARBs were compared with ACE inhibitors, or when pooling all trials together; the percentages of myocardial infarction in the overall considered populations were 5.49% for ARBs and 5.31% for other drugs.113–115 Recently, the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND trials also provided convincing evidence against the above criticism by showing the absence of a significant difference in myocardial infarction rates between telmisartan and ramipril and between telmisartan and placebo, respectively.28,29 Despite continued debate within the clinical community,116,117 the recent reappraisal of the European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology 2007 guidelines refers to the interchangeability of these two classes of drugs, the ARBs and ACE inhibitors, to prevent cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.13

Agents that inhibit the renin-angiotensin system, including ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and direct renin inhibitors, induce a compensatory rise in plasma renin by suppressing the negative feedback loop. Although renin levels prior to treatment initiation may relate to long-term cardiovascular risk,118,119 the evidence is conflicting,120 and there is no evidence that a reactive increase in renin in response to antihypertensive treatment has any cardiovascular consequences. Based on evidence from randomized controlled trials, dual renin-angiotensin system blockade with ARBs and ACE inhibitors is associated with significant increases in hyperkalemia, worsening renal function, and symptomatic hypotension.121 These adverse events have also been seen in the community setting, particularly in patients with reduced renal function at baseline.122 As a result, patients receiving dual renin-angiotensin system blockade should be monitored for renal function and serum potassium levels. Currently no evidence exists on the cardiovascular safety of the ARB/renin inhibitor combination.

An initial meta-analysis of 61,590 patients involved in ARB clinical trials reported an unexpected, modest increase in the risk of a new cancer diagnosis in patients assigned to receive ARBs compared with patients in control groups (7.2% versus 6.0%, RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01–1.15; P = 0.016).123 These results, significant only for lung cancer (0.9% versus 0.7%, RR 1.25, 1.05–1.49; P = 0.01), were mainly driven by the combination (telmisartan-ramipril) arm of ONTARGET, and by the results of the LIFE and the CHARM-Overall studies. However, there was no increase in cancer diagnosis with either monotherapy (telmisartan or ramipril) in ONTARGET, nor with telmisartan in the TRANSCEND or PRoFESS studies.

The authors of this meta-analysis123 appropriately outline its limitations, as the trials involved were not designed to explore cancer outcomes, the adjudication of cancer diagnoses was not uniform among the included studies, the analyses did not include the individual patient data for any of the trials, did not consider the latency for the malignancies, and did not take into account the effect of gender, age, smoking, or other known risk factors for malignancies. In addition, the meta-analysis combined trials with different comparators, ie, ramipril, atenolol, and placebo. It also did not include some important large trials (for example, VALUE).

Subsequent meta-analyses were not able to confirm that ARBs are associated with increased risk of cancer. Julius et al included the VALUE trial and found event rates of 1870/24, 146 (7.7%) with ARBs versus 1853/24, 123 (7.7%) with comparators.124 In an analysis of 70 randomized trials of ARBs, ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, or diuretics, Bangalore et al were able to refute a 5.0%–10.0% relative increase in the risk of cancer or cancer-related death with the use of ARBs, although they were unable to rule out increased risk of cancer with the combination of ACE inhibitors and ARBs.125

The most comprehensive assessment of ARBs and cancer to date analyzed all trials of five ARBs (candesartan, irbesartan, losartan, telmisartan, and valsartan) which enrolled ≥500 patients and had ≥12-month follow-up (total 15 trials and 138,769 patients).126 The authors had access to individual data from ONTARGET, TRANSCEND, and PRoFESS and tabulated data on cancer outcomes by treatment allocation from all major trials of irbesartan, valsartan, candesartan, and losartan. There was no association between cancer risk and any individual ARB, or with ARBs overall (4549/73, 808 [6.16%] with ARBs versus 3856/61,106 [6.31%] non-ARB control [OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.95–1.04]). Unlike the analysis by Sipahi et al,123 they were able to analyze the relationship with site-specific cancers in all 15 trials, and found no association of ARBs with lung cancer (or with the other two common site-specific cancers, ie, prostate cancer and breast cancer). The authors had access to data from several additional trials (Atrial fibrillation clopidogrel trial with irbesartan for prevention of vascular events [ACTIVE I], I-PRESERVE, and Val-HeFT), in which data on background ACE inhibitors in combination with the ARB were available, thus allowing comparison of the combination versus ACE inhibitor alone. This was in addition to the ONTARGET, VALIANT, and CHARM-Added trials in which patients were allocated to the combination or ACE inhibitor alone at randomization (total population 47,020). The incidence of cancer was 5.33% for combination ARB + ACEI versus 5.26% for ACE inhibitors alone (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.94–1.10). Overall, there was no significant difference in cancer incidence between combination therapy and ACE inhibitors.

Therefore, several meta-analyses, including the most recent one,127 using the most comprehensive data available have found no link between any ARB, or the class as a whole, and cancer. In addition, there is no clear mechanism of action known to explain any ARB-related cancer link. Furthermore, from a pathophysiologic viewpoint, the finding in the meta-analysis of increased cancer risk with ARBs in such a short time period (2–4 years) is highly improbable, given that it takes around 10 years to develop lung and other cancers from smoking. A 2010 position paper of the Italian Society of Hypertension concluded that the benefits derived from the use of ARBs outweigh the potential risks, and that the use of these drugs should be maintained according to present indications.128 In June 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration completed a review of the potential risk of cancer and concluded that treatment with an ARB medication does not increase the risk of developing cancer.129

Choosing the right ARB for an individual patient

As described in this review, it is very important to consider the individual cardiovascular disease history and risk for further cardiovascular disease events in patients when considering which ARB to prescribe. All eight currently available ARBs have demonstrated efficacy in blood pressure-lowering and are licensed for the treatment of hypertension, although there may be differences in their blood pressure-lowering efficacy and duration of action.130 Clinical trials with ARBs have been conducted in patients at different stages of the cardiovascular and renal disease continua (the cardiovascular disease prevention and renoprotection studies described here), and as a result they have different indications (Table 3). For example, in the US and Europe, olmesartan, eprosartan, and azilsartan are only indicated for the treatment of hypertension because they have not demonstrated cardiovascular disease and renal protective effects. Irbesartan and losartan are indicated for the reduction of renal disease progression in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic renal disease. Based on the results of the CHARM, VALIANT, Val-HeFT, and HEAAL studies, candesartan and valsartan (and losartan in Europe) are indicated in patients with heart failure, and losartan is indicated for stroke prevention in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy. Telmisartan is the only ARB indicated for cardiovascular prevention in a broad range of high-risk patients with or without hypertension, including those with manifest atherothrombotic cardiovascular disease (ie, a history of coronary heart disease, stroke, or peripheral arterial disease) or those with type 2 diabetes with documented target organ damage, based on the results of the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND trials.28,29

Table 3.

Indications for the eight currently available angiotensin receptor blockers

| Azilsartan | Candesartan | Eprosartan | Irbesartan | Losartan | Olmesartan | Telmisartan | Valsartan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Hypertension and type 2 diabetic renal disease | • | • | ||||||

| Prevention of stroke in hypertension and LVH | • | |||||||

| CV high risk | ||||||||

| T2DM with target organ damage Atherothrombotic |

• | |||||||

| CV disease, for example: | ||||||||

| Coronary heart disease | • | |||||||

| Peripheral arterial disease | • | |||||||

| Stroke | • | |||||||

| Heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction | • | • | • |

Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Conclusion

As effective blockers of the renin-angiotensin system, ARBs provide both antihypertensive and anti-inflammatory effects, making them an attractive and widely used therapeutic option for patients with or without hypertension (depending on the ARB) and additional cardiovascular disease risk factors or concomitant cardiovascular or renal diseases. Their favorable tolerability profiles are likely to play a key role in the maintenance of long-term adherence to these agents. This review considers the evidence from several major cardiovascular outcomes studies, which have clearly demonstrated that treatment with ARBs is protective, reduces cardiovascular risk, and provides cerebral and renal protection beyond that achieved by blood pressure-lowering alone. Direct anti-inflammatory or other pleiotropic effects beyond blood pressure-lowering may account for some of the risk reduction with ARBs and is the subject of considerable debate. Furthermore, pharmacologic differences between the ARBs impact the cardiovascular disease prevention outcome.

The currently available ARBs have demonstrated their differential efficacy along the cardiovascular and renal disease continua from patients with hypertension and early-stage cardiovascular disease, through patients with or without hypertension but at an increased cardiovascular disease risk, and, finally, to patients with significant cardiovascular and renal disease (nephropathy, left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure). For patients at high cardiovascular risk based on the results of the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies, telmisartan is indicated for cardiovascular prevention beyond that of blood pressure-lowering alone. For patients with hypertension and specific risk factors, losartan (stroke prevention in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy, or diabetic renal disease) and irbesartan (diabetic renal disease) have been shown to be effective. For patients at the highest cardiovascular risk, with heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction, candesartan, losartan, and valsartan are indicated.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Csaba Farsang has previously received fees for consultation and speaker honoraria from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Egis Rt, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Richter G Rt, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier.

References

- 1.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leal J, Luengo-Fernández R, Gray A, Petersen S, Rayner M. Economic burden of cardiovascular diseases in the enlarged European Union. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(13):1610–1619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luengo-Fernández R, Leal J, Gray A, Petersen S, Rayner M. Cost of cardiovascular diseases in the United Kingdom. Heart. 2006;92(10):1384–1389. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.072173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staessen JA, Li Y, Thijs L, Wang JG. Blood pressure reduction and cardiovascular prevention: an update including the 2003–2004 secondary prevention trials. Hypertens Res. 2005;28(5):385–407. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unger T. The role of the renin-angiotensin system in the development of cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(2A):3A–9A. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dzau VJ, Antman EM, Black HR, et al. The cardiovascular disease continuum validated: clinical evidence of improved patient outcomes: part I: Pathophysiology and clinical trial evidence (risk factors through stable coronary artery disease) Circulation. 2006;114(25):2850–2870. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmieder RE, Hilgers KF, Schlaich MP, Schmidt BM. Renin-angiotensin system and cardiovascular risk. Lancet. 2007;369(9568):1208–1219. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montecucco F, Pende A, Mach F. The renin-angiotensin system modulates inflammatory processes in atherosclerosis: evidence from basic research and clinical studies. Mediators Inflamm. 2009. Article ID: 752406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Hypertension: management of hypertension in primary care. 2006 NICE clinical guideline 34 (Partial update of NICE clinical guideline 18). Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG034. Accessed April 20, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension, The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology. Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension; European Society of Cardiology. 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(12):1462–1536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancia G, Laurent S, Agabiti-Rosei E, et al. European Society of Hypertension Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. J Hypertens. 2009;27(11):2121–2158. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328333146d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solomon SD, Appelbaum E, Manning WJ, et al. Aliskiren in Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (ALLAY) Trial Investigators. Effect of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren, the angiotensin receptor blocker losartan, or both on left ventricular mass in patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 2009;119(4):530–537. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.826214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weintraub HS, Tran H, Schwartzbard A. Potential benefits of aliskiren beyond blood pressure reduction. Cardiol Rev. 2011;19(2):90–94. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318204d9ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dzau VJ, Antman EM, Black HR, et al. The cardiovascular disease continuum validated: clinical evidence of improved patient outcomes: part II: Clinical trial evidence (acute coronary syndromes through renal disease) and future directions. Circulation. 2006;114(25):2871–2891. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(3):145–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Lancet. 2000;355(9200):253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Collaborative Study Group Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):851–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parving HH, Lehnert H, Bröchner-Mortensen J, Gomis R, Andersen S, Arner P, Irbesartan in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Microalbuminuria Study Group The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):870–878. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al. RENAAL Study Investigators Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. LIFE Study Group Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359(9311):995–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox KM, EURopean trial On reduction of cardiac events with Perindopril in stable coronary Artery disease Investigators Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study) Lancet. 2003;362(9386):782–788. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnett AH, Bain SC, Bouter P, et al. Diabetics Exposed to Telmisartan and Enalapril Study Group Angiotensin-receptor blockade versus converting-enzyme inhibition in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(19):1952–1961. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poulter NR, Wedel H, Dahlöf B, et al. ASCOT Investigators Role of blood pressure and other variables in the differential cardiovascular event rates noted in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA) Lancet. 2005;366(9489):907–913. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. ASCOT Investigators Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9489):895–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakris G, Burgess E, Weir M, Davidai G, Koval S, AMADEO Study Investigators Telmisartan is more effective than losartan in reducing proteinuria in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2008;74(3):364–369. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ONTARGET Investigators. Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(15):1547–1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yusuf S, Teo K, Anderson C, et al. Telmisartan Randomised Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects with Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9644):1174–1183. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanon S, Vijayaraman P, Sonnenblick EH, Le Jemtel TH. Persistent formation of angiotensin II despite treatment with maximally recommended doses of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with chronic heart failure. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(2):147–150. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2000.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen R, Iwai M, Wu L, et al. Important role of nitric oxide in the effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor imidapril on vascular injury. Hypertension. 2003;42(4):542–547. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000092440.52239.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nussberger J, Cugno M, Cicardi M. Bradykinin-mediated angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(8):621–622. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200208223470820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steckelings UM, Kaschina E, Unger T. The AT2 receptor – a matter of love and hate. Peptides. 2005;26(8):1401–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ong HT. Are angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers especially useful for cardiovascular protection? J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(6):686–697. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.06.090094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dicpinigaitis PV. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 Suppl):169S–173S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.169S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller DR, Oliveria SA, Berlowitz DR, Fincke BG, Stang P, Lillienfeld DE. Angioedema incidence in US veterans initiating angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Hypertension. 2008;51(6):1624–1630. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weber MA, Messerli FH. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angioedema: estimating the risk. Hypertension. 2008;51(6):1465–1467. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.111393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morimoto T, Gandhi TK, Fiskio JM, et al. An evaluation of risk factors for adverse drug events associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10(4):499–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matchar DB, McCrory DC, Orlando LA, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers for treating essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(1):16–29. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-1-200801010-00189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaput AJ. Persistency with angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) versus other antihypertensives (AHT) using the Saskatchewan database. Can J Cardiol. 2000;16(Suppl F):194A. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ries UJ, Mihm G, Narr B, et al. 6-Substituted benzimidazoles as new nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonists: synthesis, biological activity, and structure-activity relationships. J Med Chem. 1993;36(25):4040–4051. doi: 10.1021/jm00077a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurtz TW, Pravenec M. Molecule-specific effects of angiotensin II-receptor blockers independent of the renin-angiotensin system. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21(8):852–859. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de la Sierra A, Ram CV. Introduction: The pharmacological profile of eprosartan – implications for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular risk reduction. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(Suppl 5):S1–S3. doi: 10.1185/030079907X260692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song JC, White CM. Olmesartan medoxomil (CS-866). An angiotensin II receptor blocker for treatment of hypertension. Formulary. 2001;35:487–499. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burnier M. Telmisartan: a different angiotensin II receptor blocker protecting a different population? J Int Med Res. 2009;37(6):1662–1679. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edarbi Prescribing Information (FDA) Revised April 2011. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/200796s001lbl.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Asmar R. Targeting effective blood pressure control with angiotensin receptor blockers. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(3):315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kakuta H, Sudoh K, Sasamata M, Yamagishi S. Telmisartan has the strongest binding affinity to angiotensin II type 1 receptor: comparison with other angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 2005;25(1):41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ojima M, Igata H, Tanaka M, et al. In vitro antagonistic properties of a new angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker, azilsartan, in receptor binding and function studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336(3):801–808. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.176636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wienen W, Entzeroth M, van Meel JCA, et al. A review on telmisartan: a novel, long-acting angiotensin II-receptor antagonist. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2000;18:127–154. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burnier M, Brunner HR. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Lancet. 2000;355(9204):637–645. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)10365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brunner HR. The new oral angiotensin II antagonist olmesartan medoxomil: a concise overview. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16(Suppl 2):S13–S16. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]