Abstract

The elimination of persistent health inequities requires the engagement of multiple perspectives, resources and skills. Community-based participatory research is one approach to developing action strategies that promote health equity by addressing contextual as well as individual level factors, and that can contribute to addressing more fundamental factors linked to health inequity. Yet many questions remain about how to implement participatory processes that engage local insights and expertise, are informed by the existing public health knowledge base, and build support across multiple sectors to implement solutions. We describe a CBPR approach used to conduct a community assessment and action planning process, culminating in development of a multilevel intervention to address inequalities in cardiovascular disease in Detroit, Michigan. We consider implications for future efforts to engage communities in developing strategies toward eliminating health inequities.

Keywords: Community capacity, multilevel interventions, community-based participatory planning, health disparities

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), the largest contributor to all-cause mortality in the U. S., accounts for one-third of excess mortality experienced by non-Hispanic Blacks compared with non-Hispanic Whites (Wong, Shapiro, Boscardin & Ettner, 2002). Eliminating these inequities is among the highest priorities for health professionals as well as communities who experience disproportionate risk. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) offers an approach for engaging members of communities most negatively affected by health inequities in partnership with public health practitioners and researchers to develop and implement interventions to eliminate health inequities (O’Fallon & Dearry, 2002). Partnership approaches offer opportunities to address complex issues whose solutions often lie beyond the scope of any one group. Yet questions remain about how to implement such participatory processes in a manner that successfully engages local insights and expertise, and is informed by the existing base of public health knowledge.

We describe one CBPR approach used in a community planning process that culminated in the development of a multilevel intervention to reduce CVD inequities. In the Healthy Environments Partnerships’ Community Approaches to Cardiovascular Health (HEP-CATCH) project, community organizations, public health professionals, and academic research partners conducted a community assessment and action planning process that engaged representatives from predominantly African American and Latino communities with excess cardiovascular risk. The process brought together representatives from multiple sectors (e.g., urban planners, faith communities) to identify and prioritize intervention strategies, and develop a multilevel intervention. We describe the community assessment and action planning process, criteria for prioritizing potential actions, and the development of multilevel solutions to locally prioritized health concerns. We close with a discussion of implications for efforts to eliminate health inequalities.

Background

Declines in CVD risk have been uneven across socioeconomic position (SEP), race and ethnicity over the past decades, resulting in increased inequalities (Cooper et al. 2000). In Detroit, Michigan, three year average age adjusted CVD mortality rates are 1.5 times those for the state or the nation as a whole (CDC 2009; Heron et al. 2009; Michigan Department of Community Health 2007a;2007b; Schulz et al. 2005; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Within the city of Detroit, there is considerable variation in mortality rates due to cardiovascular disease, with the highest rates occurring in areas with the highest concentrations of poverty (Michigan Department of Community Health, 2004). Non-Hispanic Black and Latino residents of poor neighborhoods disproportionately bear the burden of excess cardiovascular mortality, contributing to racial and ethnic inequities in cardiovascular health (Michigan Department of Community Health, 2007). The development of multilevel interventions that effectively address multiple factors that contribute to these patterns is essential to the elimination of racial, ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in CVD.

Healthy Environments Partnership

The Healthy Environments Partnership (HEP) is a CBPR partnership established in 2000 to investigate and develop interventions to address social and physical environmental factors associated with CVD risk in Detroit neighborhoods (Schulz et al. 2005a). HEP’s research is guided by a Steering Committee (SC) comprised of representatives from the community, community-based organizations (CBOs), health agencies, and academic researchers (see Acknowledgements for a list of partners). The SC meets monthly and oversees all aspects of the research process (e.g., decisions about research questions, interpretation and application of findings).

The neighborhoods in which HEP collaborates face adverse health, environmental, and economic conditions, with excess risk of CVD mortality and risk factors, and neighborhood environments characterized by limited access to quality produce and opportunities for physical activity (Zenk et al., 2006). At the same time, there exists within these communities a sense of shared identity, skills and resources, and prior histories of positive working relationships. In addition, residents and community- and faith-based organizations share a strong commitment to the community and its health.

Conceptual framework for the Healthy Environments Partnership

The conceptual model that guided the HEP-CATCH community assessment and action planning process has been described in detail elsewhere (Schulz et al. 2005a). Here we review its basic structure, and discuss particular implications for the community assessment and planning process. The HEP conceptual model outlines relationships between fundamental factors such as race-based residential segregation and income inequalities, characteristics of the built environment (e.g., quality of parks) and social contexts (e.g., economic development), which in turn, contribute to CVD inequalities by influencing more proximate biological and behavioral CVD risk factors (Schulz et al. 2005a). This model is consistent with a body of evidence (Frohlich & Potvin, 2008; Warnecke et al., 2008) suggesting that elimination of health inequities will require multilevel interventions that attend to structural conditions that disproportionately expose some social groups to risk, as well as individual level interventions.

Partnership approaches to reduce CVD disparities

With increasing attention to health inequities, traditional research and intervention approaches have been critiqued for failing to take a multilevel, social ecological approach to change and to engage effectively such community assets as community history, values, leadership and social networks (Wallerstein, 1999). Participatory approaches arose, in part, out of efforts to engage those resources in the process of understanding and developing solutions to health and social inequities (Hatch et al., 1993; Israel et al., 1998; Stoecker & Beckwith, 1992). They build on work by Steuart (1993) suggesting that the identification of community health problems must begin within communities of identity, while solutions often require strategic engagement of extra-community resources.

A central tenet of CBPR is the equitable engagement of, for example, community residents, CBOs, governmental and service-providing agencies across multiple sectors, and academic institutions in designing, implementing and evaluating interventions toward elimination of health inequities (Israel et al. 1998). CBPR partnerships strive to address health from positive and ecological perspectives, build on strengths and resources of the involved communities, promote co-learning, equalize power among participants, and integrate knowledge acquisition and interventions for the mutual benefit of all partners (Israel et al., 2003). Together with the HEP conceptual model, these principles guided the HEP-CATCH planning process.

Community-Approaches to Cardiovascular Health (CATCH)

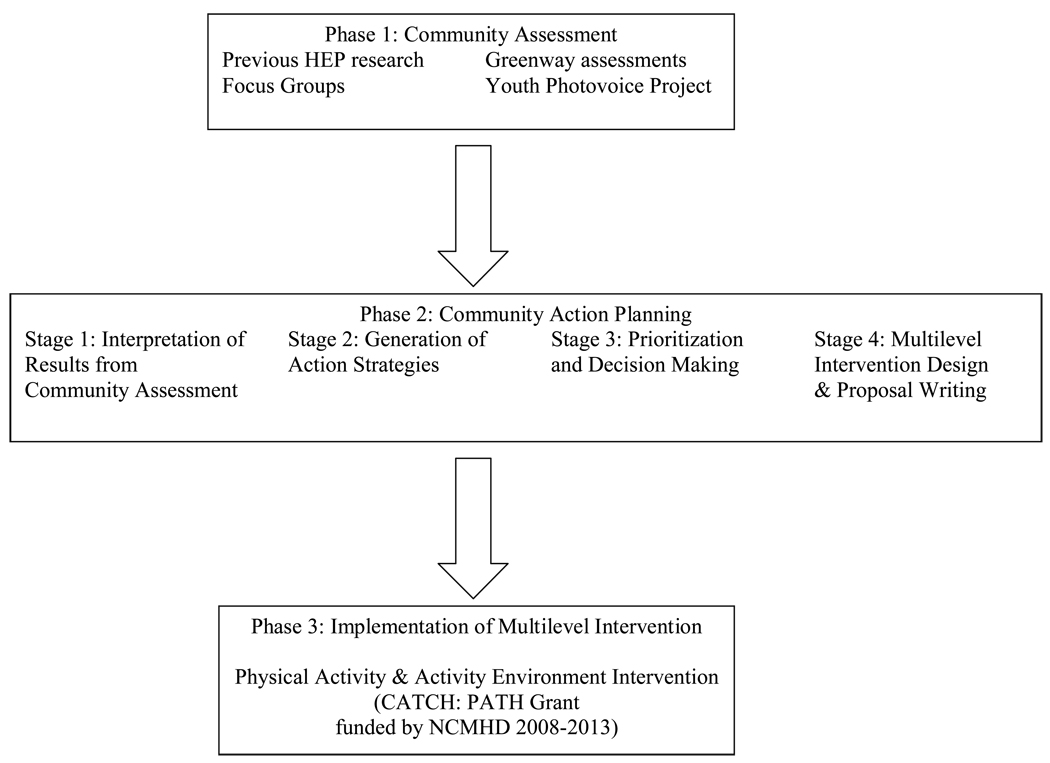

In 2005, HEP was awarded funding to conduct HEP-CATCH, a CBPR community assessment and action planning process toward development of a multilevel intervention to improve heart health in Detroit. The HEP-CATCH Planning Process consisted of three phases (Figure 1). A community assessment phase (described below) involved compiling results from several sources. A community action planning phase (described below) engaged community residents and organizational representatives from multiple sectors in examining community assessment findings, identifying priorities and prioritizing potential intervention strategies. Finally, a multilevel intervention design phase involved developing, piloting and grant proposal writing for the multilevel intervention that emerged through this process.

Figure 1.

Phases of the HEP-CATCH Community Assessment and Community Action Planning Process

Phase 1: Community Assessment: Methods, CBPR Process, and Results

The HEP-CATCH community assessment phase actively engaged youth, adults and organizations within the involved communities in analysis of neighborhood and individual factors associated with CVD. The community assessment included multiple data collection methods (Issel, 2008; Hancock and Minkler 2005, Eng, 2005), ensuring that insights were gained from diverse perspectives (e.g., community members, professionals) into multiple dimensions and levels (e.g., individual, community) associated with cardiovascular risk. These included findings from: previous HEP research (e.g., community survey, air quality analyses), focus groups, a Youth Photovoice project, and an analysis of a Greenway initiative in Detroit. We provide a brief description of each of these methods and selected results below. The following section describes the community planning process and the role of community members in interpreting and prioritizing findings from the community assessment.

Previous HEP Research

Between 2000–2005, HEP conducted a multi-method study of individual and contextual factors that contribute to CVD in the HEP communities (see Schulz et al., 2005a).

Methods and CBPR Process

Data included: 1) a stratified two-stage probability sample survey of occupied housing units in three Detroit neighborhoods focused on key CVD risk and protective factors; 2) observational assessments of neighborhood characteristics (e.g., quality of sidewalks); 3) observational assessments of food environments; 4) monitoring of air quality over a three year period; and 5) census and administrative data (Schulz et al., 2005a). The HEP SC participated actively in the study design, interpretation of results, manuscript preparation, and dissemination of findings.

Results

Key findings included: 1) negative associations between SEP and perceived stress and multiple CVD risk factors (Schulz et al., 2008); 2) positive associations between exposure to airborne particulate matter and CVD risk (Dvonch et al., 2004); 3) positive associations between social support and physical activity (Torres, Schulz, Israel, Mentz & Robinson, 2007); and 4) poor quality food environments with implications for dietary practices (Zenk et al., 2006; Zenk et al., 2009).

HEP-CATCH Focus Groups

Focus groups were conducted in the three engaged Detroit communities (2006) to elicit residents’ insights regarding challenges and facilitators for physical activity and healthy eating.

Methods and CBPR Process

Gender-, race- and language-specific (Spanish and English) focus groups were conducted at HEP CBO partner organizations. Focus groups were taped, transcribed, and analyzed to identify themes (e.g., physical activities enjoyed by residents; challenges and facilitating factors for physical activity; suggested interventions to promote physical activity).

Results

Individual and contextual challenges related to physical activity identified through this process included poor lighting, poorly maintained trails, and illicit activities in public spaces. Facilitating factors included social interaction and support, and clean and well lit activity spaces (see Table 1). Barriers and facilitating factors related to healthy eating are not presented due to space limitations.

Table 1.

Illustrative results from Phase 1: Community Assessment process regarding individual and contextual level barriers/challenges and facilitating factors for physical activity environments.

| Physical Activity Environments and Health | Barriers/Challenges | Facilitating Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Individual/ Proximate |

||

| Social Context/ Intermediate |

|

|

| Physical Context/ Intermediate |

|

|

Focus Groups with Community Residents

Youth Photovoice Project

Analysis of built environment along Greenways

HEP-CATCH Youth Photovoice Project

Twenty-four youth from involved neighborhoods were engaged in a Youth Photovoice Project (see Wang, Morell-Samuels, Hutchison & Pestronk, 2004 for a description of the use of photovoice to engage youth in community assessment processes) to assess neighborhood factors contributing to CVD.

Methods and CBPR Process

The Youth Photovoice Project was based at Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, a CBO partner of HEP. Youth took photographs to assess their neighborhoods, engaged in dialogue to link neighborhood conditions to CVD, and identified policies and community actions to address those conditions.

Results

Photovoice youth identified the following priorities: 1) increased local opportunities for youth recreation (e.g., neighborhood recreation centers); 2) improved local access to healthy foods; and 3) improved neighborhood environments (e.g., enforcement of local dumping ordinances) (Table 1). They organized a Policy Forum to present results and discuss policy options with Detroit policy makers, and were actively involved in the community action planning process described below.

Analysis of Greenways

HEP collaborated with community groups in Detroit developing new Greenways (walking or bike routes) to support and document their use.

Methods and CBPR Process

Key informant interviews, document reviews, and observations were conducted to assess planned Greenway routes and develop recommendations for physical modifications and programmatic activities to encourage use.

Results

Illustrative recommendations for physical modifications and programmatic activities along the Greenways to enhance safety and encourage use are shown in Table 1.

Phase 2: Community Action Planning Process

The HEP SC developed and implemented the community action planning process with the explicit goal of engaging a wide range of community residents, community– and faith – based organizations, multi-sectoral decision makers (e.g. urban planning, public health), and formal and informal leaders in four (4) phases of the action planning process: 1) interpretation of community assessment results; 2) generation of action strategies; 3) prioritization and decision making; and 4) designing a multilevel intervention to reduce CVD. In order to reach this goal, the SC organized several structures for participation, as follows. First, HEP CBO partners hosted Town Hall meetings in each community. These meetings offered a structure for engaging a wide range of community residents, policy makers, and community leaders in: interpreting community assessment results (phase 1 above), and generating action strategies (phase 2). The second structure for participation was an Intervention Planning Team (IPT), made up of selected community residents and leaders. The IPT provided a structure for participation to: extend the action strategies generated at the Town Hall meetings (phase 2), and identify criteria for prioritizing, and based on those criteria, recommend priority strategies for action (phase 3). Finally, the HEP partnership itself, made up of HEP SC and staff, provided the structure to design multilevel interventions and proposals for funding (phase 4), based on the priorities identified by the IPT. Objectives, participants and outcomes for each structured activity that offered opportunities for participation are summarized in Table 2, and community participants’ role in interpretation of findings, generation and prioritization of action strategies, and design of multilevel intervention are described below.

Table 2.

Objectives, participants, and outcomes for each activity that offered opportunities for participation in Phase 2: HEP-CATCH Community Action Planning process.

| Planning Process Steps | Objective | Participants | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Town Hall Meetings |

|

|

|

| Intervention Planning Team Meetings |

|

|

|

| HEP-CATCH Grant Proposal Preparation |

|

|

|

Interpretation of Community Assessment Results

HEP SC members analyzed and interpreted key study findings (Schulz et al. 2005b), and photovoice youth worked closely with project staff to distill results from their discussions of their neighborhood photographs and implications for CVD risk. We term these “internal” interpretive processes, involving those who were directly engaged with HEP-CATCH in the interpretation of findings over extended periods of time.

Following these internal interpretive processes, HEP-CATCH engaged a broader group of community members in the interpretation of the community assessment results. Town Hall meetings, hosted by CBO members of the HEP SC in each engaged community, included a brief presentation of community assessment findings, co-presented by academic and community partners from the HEP SC, and a display of photos with opportunities for discussion with youth from the Photovoice project. Presentations were followed by small group discussions in which residents contributed their insights to the interpretation of findings. For example, in discussion of findings related to air quality, participants emphasized the need to specify sources and types of air pollutants. They further pointed out that policy and regulatory bodies that influence air quality have jurisdiction over different locales (local, state, regional) with different purposes (building roads versus environmental protection), resulting in lack of coordination and communication across decision making bodies. Similarly, in group discussions of findings related to physical activity, participants pointed out that parent’s reluctance to allow their children to walk to school was multifaceted, involving difficulty and danger in crossing streets. Participants suggested that this danger was due in part to inadequate police enforcement of existing regulations, and commented that parents’ resulting decisions to drive their children to school contributed to additional challenges for pedestrians due to more traffic on roads near schools. Over 80 community residents and local policy and decision makers attended the Town Hall meetings and engaged in consideration of these findings and their implications for interventions.

Generation of Action Strategies

The second stage of the community action planning process also began at the Town Hall meetings. Following discussion of findings, participants identified potential strategies for improving cardiovascular health within each of three focal areas: air quality, physical activity, and access to healthy foods. Town Hall meetings ended with a large group discussion of strategies generated, co-facilitated by academic and community representatives from the SC. A summary document synthesized themes from small and large group discussions across all Town Hall meetings. Examples of strategies for addressing physical activity and activity environments from this stage of the process are shown in Table 3, column 1 (strategies to address food access and air quality are not shown due to space limitations).

Table 3.

Illustrative results from each stage of the HEP-CATCH community action planning process, including intervention strategies generated (1), prioritized (2), and incorporated into multilevel intervention design (3) to reduce cardiovascular risk through increased physical activity and promotion of environments conducive to physical activity.*

| Levels of Multilevel Intervention |

Potential Intervention Strategies Generated (1) |

Intervention Strategies Prioritized (2) |

Multilevel Intervention Design (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual/ Proximate |

Develop programs & events that are fun & encourage physical activity1,2 (e.g. programs that engage youth & families; group walks with city leaders; activities involving friendly competition) Disseminate information about events & opportunities to be active, e.g. through grocery store bulletins, church newsletters1 |

Encourage development of knowledge, skills, & opportunities to incorporate physical activity into daily lives2 | Develop neighborhood-based walking groups to support physical activity, encompassing information, skill building, social support and group walks3 |

| Social Context/ Intermediate |

Train community members as physical activity instructors1 Work with local churches, & schools to open their facilities to the wider community1, 2 Build on existing community physical activity programs1 Adopt neighborhood recreational spaces & promote greater use of these spaces2 Identify funding opportunities for community physical activity programs, e.g. sponsors, donations, legislation1 |

Work with churches & CBOs to develop & implement programs within the context of their existing activities2 Engage organizations, corporations, school & community groups to maintain recreation spaces & promote community ownership, e.g. adopt-a-block program, planting community gardens2 Facilitate linkages with existing athletic groups (e.g. walking clubs, athletic teams, nearby schools) to promote use of the greenways2 Work with businesses near greenways to develop walking clubs for employees2 |

Build capacity within community and faith-based organizations to support active living3 Provide training & support for community residents to become walking group leaders1 Provide ongoing training & technical assistance for representatives of community and faith-based organizations interested in establishing walking programs3 Provide small grants & technical assistance to community groups & residents to promote active engagement in supporting public green spaces3 |

| Physical Context/ Intermediate |

Assure safety from crime and motor vehicles1 Improve transportation to recreational spaces1 Explore alternative sites for physical activity Create additional spaces for physical activity, e.g. greenways, indoor facilities1 |

Work with the city to advocate a strong police presence near recreational spaces Designate businesses and homes near greenways as safe places2 Work with local groups to promote infrastructure development to assure safety and visual appeal of recreational spaces, e.g. lighting, signs, benches, water fountains, emergency phones2 |

Implement a mini-grant program to support the efforts of community groups/residents to promote improvements to parks and greenways to promote environments conducive to active living3 (e.g., community art projects in parks or greenways) Work with Greenway organizations to promote Greenway development & maintenance.2 |

Results from the first stage, interpretation of findings from the community assessment phase, are not included.

Results from Town Hall Meetings

Results from Intervention Planning Team Meetings

Multilevel Intervention Design

Prioritizing and Decision Making

The Intervention Planning Team (IPT), a group of 24 key representatives from the involved communities and Detroit City, prioritized the action strategies identified through the Town Hall meetings and recommended goals and strategies for a multilevel intervention to reduce CVD in Detroit. Criteria that the SC used to identify IPT members included: representation from involved communities; citywide perspective and influence; multiple sectors (e.g., public health, urban planning); and balance of organization types (e.g., faith-based, environmental justice).

IPT members participated in Town Hall meetings, and received a copy of the summary document compiled from those meetings prior to the first IPT meeting. In the first meeting of the IPT, members met in small thematic groups (e.g., one on air quality, one on food access, one on physical activity) facilitated by a member of HEP. Each small group discussed potential action strategies and began to identify priority strategies for further consideration, identifying those about which they were most passionate, those which might have the greatest impact on cardiovascular risk, and those that might affect the greatest number of people or the most vulnerable groups. Following the first meeting of the IPT, HEP staff compiled Evidence-Based Reviews that summarized the state of knowledge regarding effectiveness of those strategies that had begun to emerge in each of three focal areas (food access, physical activity, air quality), across multiple levels of intervention. Staff undertook a comprehensive review of literature on interventions in each of these areas published in the previous decade, and reviewed articles for intervention components and objectives, populations, evaluation methods, and findings. Strategies were rated as: “Best Practices” if there was strong evidence of effectiveness in communities similar to the Detroit HEP neighborhoods (e.g., urban, lower income communities, non-Hispanic Black or Latino communities); “Promising Strategies” if there was limited evidence of effectiveness (e.g., evidence of effectiveness in suburban or predominantly white communities, or evidence of partial effectiveness); “Strategies that Don’t Seem to Work” if there was evidence that the strategy was not effective; and “No Evidence/No Information” if we were unable to locate information about the effectiveness of a strategy.

The IPT developed a set of recommendations for priority interventions to reduce CVD in Detroit at their second meeting, incorporating insights from the Evidence-Based Review. They recommended that the multilevel intervention build on and engage existing resources, programs and institutions within the communities. Priority strategies recommended for promoting physical activity, across multiple levels, are shown in Table 3, column 2 (priorities for air quality and food environments are not shown due to space limitations).

Design of Multilevel Intervention

The HEP SC reviewed and synthesized recommendations from the IPT, and determined the specific scope and outcomes for a multilevel intervention to promote cardiovascular health. SC members created a broad vision that encompassed walkable built environments, clean air, access to healthy foods and economic development. Based on IPT recommendations, prioritized intervention strategies were those that: 1) built on and enhanced existing community resources; 2) strengthened the capacity of local groups and organizations to support cardiovascular health; 3) considered the evidence base for community-identified priorities; and 4) built on collective experiences and skills within HEP. Priority areas that emerged were: 1) promotion of active lifestyles and activity friendly environments, with Detroit Greenways as a focal point; and 2) promotion of food access and economic stability. The SC decided to focus initially on the first priority.

Working from the identified multilevel strategies, and prioritizing efforts that build on and strengthen existing community resources, HEP developed specific objectives and an implementation plan for a multilevel intervention. The resulting design included: 1) development, implementation and evaluation of walking groups; 2) enhancing skills and experience among community residents to lead walking groups; 3) developing a network of community and faith-based organizations to support walking groups; and 4) supporting changes in built, social and policy environments to promote physical activity and cardiovascular health (Table 3, column 3). This design became the basis for the Community Approaches to Cardiovascular Health: Pathways to Heart Health proposal (subsequently funded by NCMHD).

Discussion

The CBPR approach described here engaged multiple groups, perspectives, and expertise in the development of strategies to address CVD inequities. Results highlight the critical role of social and physical environments, and support the idea that CBPR offers a mechanism for developing intervention strategies that explicitly recognize contextual effects on health (Warnecke et al., 2008). In addition, we suggest CBPR approaches can move beyond recognizing context, to engage and strengthen social contexts, contributing to enhanced community capacity to address health inequities. We discuss these distinct contributions below.

Intervention Strategies that Recognize Contextual Effects on Health

The HEP-CATCH assessment and planning process brought context squarely into the foreground, emphasizing aspects of the social and the physical environment that shaped residents’ cardiovascular health. Recommended strategies encompassed both individual and contextual change. For example, strategies identified to facilitate physical activity included the development of walking clubs, promotion of community ownership, and community presence in public outdoor places to increase safety. Participants emphasized strategies that were fun, interactive, that considered both social and physical contexts. Promoting walking is an individual behavioral change, located in our conceptual model at the proximate level. However, structuring walking within small groups, rather than as solely an individual activity, recognizes contextual factors that create challenges (e.g., concerns about safety), as well as facilitators for physical activity (e.g., social support) (Bjaras, Harberg, Sydhoff & Ostenson, 2001; Kahn et al., 2002).

Planning process participants also identified strategies that more directly change social and physical contexts. For example, activities that are social, fun, and that engage community members, particularly youth, providing training, job skills, and jobs (i.e., as physical activity leaders) to support economic opportunities and broaden the base of skills within the community; and promoting safety through, for example, enhanced police presence, each change social contexts in ways that can promote physical activity. Strategies to change physical contexts to promote physical activity included: traffic calming devices (e.g., speed bumps); repairing sidewalks; creating community gardens as destinations for walkers; maintaining public parks or trails; and providing transportation for youth to recreation centers since many lived in neighborhoods without a local center. These results are consistent with the claim that CBPR approaches help to recognize contextual factors that influence community health (Warnecke et al. 2008). In the following section we consider how a CBPR planning process may move beyond recognition of contextual factors, to explicitly build on, strengthen, or otherwise enhance the capacity of communities to work together toward elimination of health disparities.

Enhance Community Capacity to Eliminate Health Inequities

Communities’ capacity to influence decisions that affect physical and social environments (e.g., local land uses, social policies) have critical implications for health inequities (Freudenberg, 2004). Here we focus on three priorities that emerged through the HEP-CATCH community planning process that are consistent with key dimensions of community capacity to promote environmental health: community leadership, social and organizational networks, and active participation of a broad cross section of participants (Freudenberg, 2004).

Planning process participants emphasized strategies that featured community leadership. Town Hall meetings were hosted by CBO partners in HEP and representatives from those CBOs played key roles in presenting findings at Town Hall meetings, reflecting explicit decisions to foreground community leadership. HEP community partners determined criteria for, and identified individual members of, the IPT, building on existing leadership roles and extending social and organizational networks within the community.

Recognizing and building community leadership also emerged as a criterion for the multilevel intervention during the community action planning process (see “Outcomes” from IPT meetings, Table 2). This criterion influenced the multilevel intervention design in several ways, including: 1) building community leadership for health promotion by hiring, training and extending skills of community members as Community Health Promoters; 2) engaging existing leadership in promoting cardiovascular health through training and financial resources to local faith, community-based, educational and other organizations interested in supporting walking groups; 3) promoting new leadership by providing financial and technical support to local groups interested in promoting social or physical environments conducive to physical activity; and 4) working in partnership with local leaders in decisions about the intervention, land use and community engagement more broadly. Such strategies promote cardiovascular health while simultaneously building on existing, and supporting the emergence of new, community leadership to strengthen communities’ capacity to promote health.

The HEP-CATCH community action planning process sought to develop and strengthen social and organizational networks, and this priority was independently affirmed by community participants. The action planning process built on and extended long-standing relationships among the HEP partner organizations, with leadership from CBO partners. The planning process also built new relationships across multiple communities and multiple sectors, including residents, faith and community-based organizations, racial and ethnic groups that have historically been isolated from each other in Detroit, and representatives from public health, urban planning, and community development. These relationships were particularly apparent in the IPT, as representatives from multiple sectors and communities engaged in strategic planning with a mutual commitment to improve cardiovascular health in Detroit.

Participants in the action planning process affirmed the importance of intervention strategies that build on existing resources within, and support relationships between, community organizations. One example is an emphasis on the development of a network of community and faith-based organizations with the skills, resources, and commitment to support walking groups as a priority. Such a network not only expands opportunities for physical activity and promotes activity-friendly social environments, but also builds on and strengthens the critical role local organizations play in sustaining communities that are disproportionately at risk for CVD. It strengthens the potential for change beyond any one specific intervention, to enhance community capacity to promote health more broadly through strengthened community and organizational networks.

The third dimension of community capacity that cross-cut the action planning process was the priority placed on engaging multiple groups and sectors. A fundamental principle of CBPR, and increasingly recognized as a critical aspect of interventions to address social determinants of health inequities, such broad representation attempts to assure engagement of a depth and breadth of perspectives and insights in the analysis, synthesis, interpretation and generation of action strategies. Thus, for example, the HEP SC’s emphasis on a broad cross section of representation on the IPT reflects a commitment to the integration of diverse perspectives and resources, and identification of shared commitments and priorities that are a foundation for subsequent collaboration and resource sharing.

Concluding Comments: Toward the Elimination of Health Inequities

The multilevel strategies that emerged from the HEP-CATCH community assessment and planning process suggest that the active engagement of representatives from communities most negatively affected by health disparities, in partnership with representatives from multiple sectors, can contribute to development of multilevel solutions to health inequities. Residents’ awareness of social processes that influence health within their communities is a critical resource for addressing health inequities. Processes that emphasize community leadership, build on and extend social and organizational networks, and engage a broad cross section of local organizations in addressing community health, can simultaneously promote health and enhance long term capacity for promotion of health equity (Marmot 2007). Expanding leadership, networks, capacities, and partnerships to engage resources and insights beyond local communities, toward creation of more equitable social and economic policies, will be essential to reach the ultimate goal of eliminating health inequities.

Acknowledgement

The Healthy Environments Partnership (HEP) is affiliated with the Detroit Community–Academic Urban Research Center. We thank the members of the HEP Steering Committee for their contributions to the work presented here, including representatives from Brightmoor Community Center, Detroit Department of Health and Wellness Promotion, Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, Friends of Parkside, Henry Ford Health System, Rebuilding Communities, Inc, the University of Michigan School of Public Health and community members at large. The work presented here was supported through a grant from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R24 MD 001619), and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Kellogg Health Scholars Program, and we thank both for their leadership in developing innovative strategies to support long-term commitments to CBPR partnership endeavors.

References

- Bjärås G, Härberg LK, Sydhoff J, Östenson CG. Walking campaign: A model for developing participation in physical activity? Experiences from three campaign periods of the Stockholm Diabetes Prevention Program (SDPP) Patient Education and Counseling. 2001;42(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, & National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics Report. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Retrieved January 12, 2008];Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. 2007 from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/cdi/SearchResults.aspx?IndicatorIds=26,1,33,37,2,15,3,4&StateIds=46&StateNames=United%20States&FromPage=HomePage.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Retrieved August 13, 2009];Compressed Mortality, 1999–2006. from http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html.

- Cooper R, Cutler JA, Desvigne-Nickens P, Fortmann SP, Friedman L, Havlik R, et al. Trends and disparities in coronary heart disease, stroke and other cardiovascular diseases in the United States: Findings of the national conference on cardiovascular disease prevention. Circulation. 2000;102:3137–3147. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvonch JT, Brook RD, Keeler GJ, Rajagopalan S, D'Alecy LG, Marsik FJ, et al. Effects of concentrated fine ambient particles on rat plasma levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine. Inhalation Toxicology. 2004;16:473–480. doi: 10.1080/08958370490439678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng E, Moore K, Rhodes SD, Griffith D, Allison L, Shirah K, et al. Insiders and outsiders assess who is "the community": Participant observation, key informant interview, focus group interview, and community forum. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker E, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N. Community capacity for environmental health promotion: Determinants and implications for practice. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(4):472–490. doi: 10.1177/1090198104265599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: The inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:216–221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock T, Minkler M. Community health assessment or healthy community assessment: Whose community? Whose health? Whose assessment? In: Minkler M, editor. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. 2nd. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 138–157. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch J, Moss N, Saran A, Presley-Cantrell L, Mallory C. Community research: Partnership in black communities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1993;9 6 Suppl:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tehada-Vera B. Deaths: Final data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Report. 2009;57(14):1–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Issel LM. Community health assessment for program planning. In: Issel LM, editor. Health Program Planning and Evaluation: A Practical Systematic Approach for Community Health. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2008. pp. 115–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, Heath GW, Howze E, Powell KE, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22 4 suppl:73–107. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. Achieving health equity: From root causes to fair outcomes. The Lancet. 2007;370:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michigan Department of Community Health. [Retrieved April 30, 2007];Detroit Department of Health, three year age adjusted average CVD mortality rates (2000–2002) 2004 from http://www.mdch.state.mi.us/pha/osr/CHI/CRI/frame.asp.

- Michigan Department of Community Health, Vital Records & Health Data Development Section. [Retrieved January 13, 2009];1989 – 2006 Michigan Resident Death Files. 2007a http://www.mdch.state.mi.us/pha/osr/chi/CRI/CriticalInd/CRIST.asp?TableType=Heart%20Disease&CoName=Michigan&CoCode=0.

- Michigan Department of Community Health. [Accessed 2009];Age-Adjusted Death Rates for Ten Leading Causes by Race and Sex Michigan Residents, 2007. 2007b http://www.mdch.state.mi.us/pha/osr/chi/Deaths/leadadj/adjstate.asp?Dxid=0&CoName=Michigan&CoCode=0.

- Minino AM, Smith BL. Deaths: preliminary data for 2000. National Vital Statistics Report. 2001;49(12):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Fallon LR, Dearry A. Community-based participatory research as a tool to advance environmental health sciences. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110:155–159. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Kannan S, Dvonch JT, Israel BA, Allen A, James SA, et al. Social and physical environments and disparities in risk for cardiovascular disease: The Healthy Environments Partnership conceptual model. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005a;113:1817–1825. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Zenk S, Kannan S, Israel BA, Koch MA, Stokes C. Community-based participatory approach to survey design and implementation: The Health Environments Partnership Survey. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker E, editors. Methods for Conducting Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005b. pp. 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, House JS, Israel BA, Mentz G, Dvonch JT, Miranda PY, et al. Relational pathways between socioeconomic position and cardiovascular risk in a multiethnic urban sample: complexities and their implications for improving health in economically disadvantaged populations. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2008;62:638–646. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.063222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuart GW. Social and cultural perspectives: Community intervention and mental health. Health Education Quarterly. 1993;20 Supplement 1:99–111. doi: 10.1177/10901981930200s109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecker R, Beckwith D. Advancing Toledo's neighborhood movement through participatory action research: Integrating activist and academic approaches. Clinical Sociology Review. 1992;10:198–213. [Google Scholar]

- Torres E, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Mentz G, Robinson M. Predictors of physical activity in eastside, northwest and southwest Detroit. 3rd National Conference, Creating Research Careers: Your Pathway to Success; San Antonio, TX: National Coalition of Ethnic Minority Nurse Associations; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health United States 2001. 2001 doi: 10.3109/15360288.2015.1037530. PHS 01-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. Power between evaluator and community: Research relationships within New Mexico's healthier communities. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;49:39–53. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Morell-Samuels S, Hutchison PM, Pestronk RM. Flint photovoice: Community building among youths, adults, and policymakers. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:911–913. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke RB, Oh A, Breen N, Gehlert S, Paskett E, Tucker KL, et al. Approaching health disparities from a population perspective: the National Institutes of Health Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1608–1615. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:1585–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenk S, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, James SA, Bao S, Wilson ML. Fruit and vegetable access differs by community racial composition and socioeconomic position in Detroit, Michigan. Ethnicity & Disease. 2006;16:275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Kannan S, Lachance L, Mentz G, Ridella W. Neighborhood retail food environment and fruit and vegetable intake in a multiethnic urban population. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2009;23:255–264. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.071204127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]