Abstract

Stigma against those with schizophrenia has demonstrated deleterious effects. However, less is known about the experience of individuals who disclose this diagnosis and how such disclosures differ by social situations. This study examines diagnosis disclosure in different contexts. A convenience sample of 258 adults with schizophrenia recruited via the internet and e-mail lists completed an online survey. Subjects were more open about their diagnosis with doctors, parents and friends than with employers or police. Those who report very good current mental health or who had fewer types of relationships were more open overall. Although reactions to disclosure varied, many report worse treatment by police and better treatment by parents after disclosure. Many also experienced worse treatment for medical problems after disclosing their schizophrenia diagnosis. These results support targeted anti-stigma interventions. It also suggests that stigma must be understood through individual experience in specific contexts rather than as a unitary experience.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Psychosocial, Stigma, Healthcare disparities, Police

Introduction

Stigma is a broad term that includes direct discrimination and systemic discrimination (Link et al. 2001), as well as anticipation of discrimination (Thornicroft et al. 2009). The stigma of schizophrenia has been studied extensively in many cultures and has been shown to have a variety of negative impact on finance, quality of life, (Thornicroft et al. 2009) and recovery (Yanos et al. 2008). Healthcare professionals are not immune to these biases and negative attitudes have been found at greater rates in non-psychiatric settings than in psychiatric settings (Bjorkman et al. 2008; Chin and Balon 2006).

Most studies of discrimination against those with schizophrenia assessed the attitudes of the general public in different cultures (Angermeyer and Matschinger 2005; Anglin et al. 2006; Link et al. 1999a; Nakane et al. 2005). Fewer studies have examined the expectation and subjective experience of discrimination by those with schizophrenia (Dickerson et al. 2002; Ertugrul and Ulug 2004; Thornicroft et al. 2009; Yanos et al. 2008) and most of these utilized small samples with a few exceptions (Lee et al. 2005; Thornicroft et al. 2009; Wahl 1999). One of the largest surveys of this kind in the United States was conducted by Otto Wahl using a sample of 1,301 individuals with mental illness recruited from the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) but less than 20% of this sample identified as having a Schizophrenia spectrum disorder. The results for this group are not separated out. Given the observed differences in attitudes towards people with schizophrenia versus those with depression (Nordt et al. 2006), it is unclear whether these findings can be generalized to individuals with schizophrenia. The Wahl study is unusual in that it identified how commonly discrimination, prejudice, or support is experienced in specific social situations. Such data is essential to optimally target interventions. A framework that separately considers the experience or expectation of discrimination in different social contexts may also support or challenge proposals that stigma is related to a lack of familiarity (Corrigan et al. 2001), that it is related to “unrealistically elevated fear of violence” (Link et al. 1999a), that it is related to perceptions of treatability or that it is not related to beliefs about etiology (Angermeyer and Matschinger 2005).

A study from Hong Kong (Lee et al. 2005) and the international study of stigma by the INDIGO study group (Thornicroft et al. 2009) both provide large diagnosis-specific study of the experience of stigma by individuals with schizophrenia. The consistency of methodology in the INDIGO study allows for a rare comparison of stigma in different countries but despite the scale of the study, the authors acknowledge that they were not “able to investigate in any detail the complex features of stigma and discrimination that might apply in culture or context specific settings.”

This article reports on the first large-scale study examining to whom Americans with schizophrenia disclose their diagnosis, whether they experience positive, negative or neutral reactions to such disclosures and some specific consequences of prior disclosures.

Methods

The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) commissioned Harris Interactive to conduct an online survey of people living with schizophrenia, recruited via NAMI e-mail lists and the NAMI website. The survey was executed between February 11 and February 19, 2008. The survey questions were developed by a panel that included the authors in consultation with Harris Interactive. Completion of the survey averaged 17 min.

This survey was restricted to individuals over the age of 18 who self-identified as having schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or another schizophrenia spectrum disorder. This data was not weighed for demographic factors or propensity to be online. The survey also included questions about knowledge and perceptions of the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Those results are available online (http://www.nami.org/Content/NavigationMenu/SchizophreniaSurvey/Analysis_Living_with_Schizophrenia.htm) and will be analyzed in a separate article. This study will focus on the sections of the survey that describe sources of support as well as positive and negative experiences of individuals who self-identify as having schizophrenia.

Descriptive statistics such as percent frequencies for categorical data and means and standard deviations for continuous data were computed. As most data were not normally distributed, Spearman rank correlations were computed to investigate the interrelationships between measures. Step-wise regression techniques, both linear and logistic, were used to model factors of interest with inclusion/exclusion criteria of P < 0.15. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS v9.1 computer software package. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

The current post-hoc analysis of the data from Harris Interactive was based on a de-identified dataset. This protocol was therefore deemed exempt from review by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center IRB. The initial Harris Interactive study was made possible with funds from AstraZeneca, Solvay, and Wyeth. This post-hoc analysis did not require any additional funding and the authors do not have any material conflicts of interest to report.

Results

A total of 258 people self-reporting a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder qualified and completed the survey. See Table 1 for general demographic characteristics. The sample was predominantly white and 55% were women. The average age was 41.8. Only 38% of the sample was employed.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Gender | |

| Male (%) | 45 |

| Female (%) | 55 |

| Age | |

| 18–24 (%) | 8 |

| 25–34 (%) | 20 |

| 35–44 (%) | 28 |

| 45–54 (%) | 28 |

| 55–64 (%) | 14 |

| 65+ (%) | 1 |

| Mean | 41.8 |

| SD | 11.5 |

| Race | |

| Caucasian (%) | 78 |

| African-American (%) | 4 |

| Hispanic (%) | 7 |

| Other (%) | 9 |

| Education | |

| HS or less (%) | 17 |

| Some college (%) | 46 |

| College or more (%) | 37 |

| Employment | |

| Employed (%) | 38 |

| Unemployed (%) | 41 |

| Retired (%) | 11 |

| Student (%) | 17 |

| Homemaker (%) | 11 |

| Income | |

| Less than $35 K (%) | 65 |

| $35 K–$74,999 (%) | 18 |

| $75 K–$99,999 (%) | 5 |

| $100 K or more (%) | 5 |

| Decline to answer (%) | 8 |

| Current MH | |

| Poor/Fair (%) | 58 |

| Status | |

| Good (%) | 24 |

| Very good/Excellent (%) | 17 |

| Decline to answer (%) | 8 |

Individuals with schizophrenia varied in how open they reported they were about their diagnosis depending on their relationship with the other person (See Table 2). All openness scores were rated by participants on a scale of 1 (not at all open in disclosing diagnosis) to 4 (completely open regarding diagnosis). The response rate for each type of relationship varied as many subjects did not have particular types of relationships. Response rates were lowest for relationships with spouse/significant others and with children with only about half of the respondents indicating that they had such relationships. The highest mean openness scores were for the categories of doctors and spouses/significant others with mean scores of 3.6 and 3.3, respectively where 3 corresponds to quite a bit open about one’s diagnosis of schizophrenia and 4 corresponds to completely open about their diagnosis. Neighbors had the lowest mean openness score of 1.7 where 2 would correspond to somewhat open about one’s schizophrenia diagnosis and 1 correspond to not at all open about one’s schizophrenia diagnosis.

Table 2.

Openness scores by type of relationship

| Mean score | SD | Response rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | |||

| Parents | 3.3 | 1.0 | 239 | 93 |

| Extended family | 2.6 | 1.1 | 251 | 97 |

| Spouse/significant other | 3.4 | 1.0 | 153 | 59 |

| Children | 2.3 | 1.3 | 146 | 57 |

| Friends | 2.7 | 1.0 | 254 | 98 |

| Coworkers | 2.1 | 1.1 | 178 | 69 |

| Employer | 2.2 | 1.2 | 177 | 69 |

| Place of worship | 2.0 | 1.1 | 177 | 69 |

| Neighbors | 1.7 | 0.9 | 248 | 96 |

| Doctors | 3.6 | 0.7 | 256 | 99 |

| Law enforcement | 2.0 | 1.1 | 183 | 71 |

| Overall mean score | 2.6 | 0.7 | 258 | – |

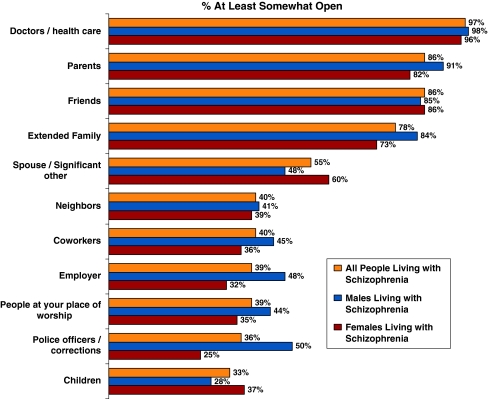

To consider the potential availability of support from a particular type of relationship, the percentage of all respondents who identify being at least somewhat open about their diagnosis was calculated for each relationship type (see Fig. 1). Most individuals with schizophrenia were not open about their diagnosis with children, police/correction officers and persons at their place of worship. Only 25% of women reporting being at least somewhat open with police/correction officers compared to 50% of men.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of subjects who report being at least somewhat open about their schizophrenia diagnosis with specific individuals or groups

Although this survey did not directly ask about levels of social isolation, the number of different types of relationships for each respondent was calculated as a proxy. The mean number of types of relationships for respondents to this survey was 8.8 relationships with a standard deviation of 1.8.

Across all relationships, an average openness score was computed for each participant, again on a scale of 1 (not at all open) to 4 (completely open). In examining overall openness scores, we found a negative correlation with the number of types of relationships a respondent had (r s = −0.340, P < 0.001) and positive correlation with the rating of current mental heath status (r s = 0.302, P < 0.001). No other factors had strong correlations with overall openness. The results of the step-wise linear regression analysis of an individual’s average openness score are presented in Table 3. In the unadjusted analysis, only the self-reported current mental health status and the number of types of relationships significantly predicted overall level of openness. In the adjusted analysis, these two predictors remained significant after controlling for gender, race, marital status, physical health, income, and employment status. However, these two factors individually do not account for a large portion of the variability in mean openness scores, with each having a low partial correlation coefficient. Other unmeasured factors might be more influential on openness given that the adjusted analysis model had a low overall r 2 = 0.222.

Table 3.

Results of step-wise linear regression in determining predictors of openness score

| Variable | Probability value (P) | Coefficient | SE | Partial correlation (r 2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysis | ||||

| Age | 0.7038 | ||||

| Age of onset | 0.3638 | ||||

| Years treated | 0.3026 | ||||

| Female | 0.3328 | 0.1209 | −0.1305 | 0.0838 | 0.0102 |

| Caucasian | 0.2765 | 0.0636 | 0.1920 | 0.1030 | 0.0115 |

| Receiving treatment | 0.7420 | ||||

| Family member diagnosed | 0.1740 | ||||

| Education | 0.6937 | ||||

| Current mental health | |||||

| Good | 0.0770 | 0.0115 | 0.2585 | 0.1015 | 0.0076 |

| Very good | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.7204 | 0.1358 | 0.1018 |

| Physical health (very good) | 0.4916 | 0.0791 | −0.2128 | 0.1207 | 0.0127 |

| Employment status | 0.4215 | 0.1286 | 0.1460 | 0.0957 | 0.0085 |

| Marital status | 0.1238 | 0.0242 | 0.2283 | 0.1006 | 0.0138 |

| Income < $25 k | 0.2195 | ||||

| # of Relationships (response rate) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | −0.1730 | 0.0288 | 0.1051 |

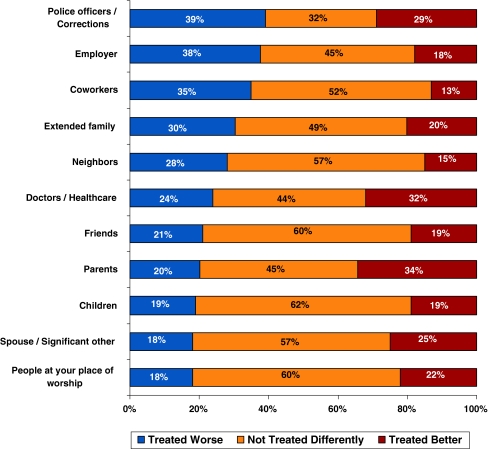

For all different types of relationships, some individuals with schizophrenia report being treated better, some worse and some report being treated no differently (see Fig. 2). More individuals with schizophrenia report being treated worse by police/correctional officers than any other group and more report being treated better by parents than any other group. Although relatively few people are open about their schizophrenia at their place of worship, among those who are open only 18% report being treated worse compared to 22% who report being treated better and a majority who report being treated no differently.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of subjects who report being treated better worse or no better by specific individuals or groups after disclosing their diagnosis

To further investigate the treatment experience of our subjects by doctors, the sample responding to that question were dichotomized (treated worse versus treated the same or better) and logistic regression modeling was used to identify characteristics of the subjects who perceived being treated worse by their doctor after revealing their diagnosis (see Table 4). A total of 250 subjects reported revealing their diagnosis to their doctor and 61 of these reported being treated worse. In the unadjusted analysis, only gender was a statistically significant predictor of perceiving worse treatment by doctors. In the adjusted analysis, gender, employment status, and age of onset were statistically significant factors predicting perceived worse treatment. Individuals with an earlier age of disease onset were less likely to perceived worse treatment, as were those who were employed. However, women were 2.5 times more likely than men to perceive worse treatment from their physicians after disclosing their diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Table 4.

Results of logistic regression in determining predictors of perceiving worse treatment by doctors after disclosing diagnosis

| Variable | Probability value (P) | Odds ratio | (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysis | |||

| Age | 0.3065 | |||

| Age of onset | 0.0537 | 0.0220 | 0.959 | (0.924, 0.994) |

| Years treated | 0.3631 | |||

| Female | 0.0455 | 0.0087 | 2.476 | (1.257, 4.878) |

| Caucasian | 0.6680 | |||

| Receiving treatment | 0.4634 | |||

| Family member diagnosed | 0.8447 | |||

| Education | 0.5832 | |||

| Current mental health (very good) | 0.1736 | |||

| Physical health | 0.4728 | |||

| Employment status | 0.3606 | 0.0480 | 0.494 | (0.245, 0.994) |

| Marital status | 0.2178 | |||

| Income | 0.6910 | |||

| Level of openness (completely) | 0.1238 | |||

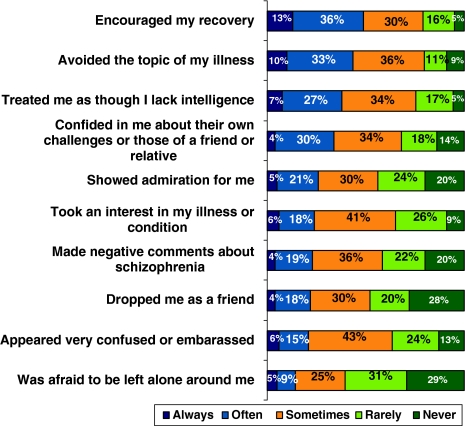

Individuals with schizophrenia describe a variety of specific positive and negative experiences around their diagnosis with positive experiences (ex., encouraging their recovery, taking an interest in their condition/disease) among the most common reactions (Fig. 3). However, a large majority report experiencing some negative reactions in this survey: 85% reported being treated as if they lack intelligence, 80% reported hearing negative comments and 71% reported that someone was afraid to be left alone around them. More than a third reported that they never or rarely experienced others taking an interest in their condition, 91% reported that someone has avoided the topic of their illness at least once, and more than half reported that someone they relied upon became more distant since their diagnosis.

Fig. 3.

Percent or subjects who experienced specific positive and negative reactions since being diagnosed

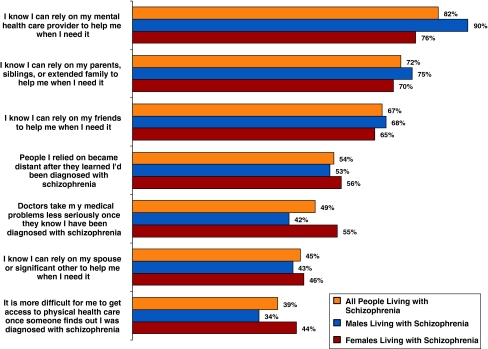

A larger percentage of subjects report being able to rely on their mental health provider than family or friends (Fig. 4). However, about half of all respondents report that their medical conditions are not taken as seriously when doctors know of their schizophrenia. More women than men report difficulties getting their medical conditions taken seriously and report that it is more difficult to get access to physical health care when their diagnosis of schizophrenia is known, consistent with the findings that women are more likely to report being treated worse after disclosing a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of individuals with schizophrenia who agree or strongly agree with the following statements

Discussion/Conclusion

Taken together the findings of this survey suggest that many people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder are well aware of social stigma and that their experience of such stigma varies in different social settings. This is consistent with findings from an earlier US study of serious mental illnesses (Wahl 1999) and from schizophrenia studies that include data from other countries (Thornicroft et al. 2009). While this survey does not directly ask for their emotional responses to the limited supports and negative reactions, it is clear that stigma impacts their lives in ways that most people would experience as profoundly painful.

Those who report better current mental health were more open overall about their diagnosis. This pattern could be explained if individuals believe that their diagnosis will be better received when they are not perceived as currently impaired by schizophrenia. However, this correlation also suggests that those who are currently suffering are more isolated.

The correlation between a greater variety of relationship types and lower overall openness can be explained if the social skills that increase the range of socialization also increase awareness of stigma.

A larger percentage of women reported being at least somewhat open about their diagnosis with their spouse or significant other while a larger percentage of men reported being open with their employers and with police/correctional officers. It is unclear whether this difference is due to gender differences in the rates of intimate relationships, employment or contact with the justice system. These gender differences as well as the overall pattern of diagnosis disclosure provide valuable information to help focus the scenarios that are practiced within psychiatric rehabilitation, cognitive-behavioral treatment and social skills training for individuals with schizophrenia.

Although recent studies have demonstrated that spirituality and religion can play a profound role for large fractions of individuals with schizophrenia (Mohr et al. 2006), in our sample, only 39% disclose their schizophrenia diagnosis in their places of worship. Taken together with the relatively positive response experienced by those who do disclose their diagnosis in this setting (only 18% report being treated worse), our findings suggest that places of worship may be an underutilized avenue of support. However, this opportunity should be viewed within the context of a recent study that suggests that only about 22% of Americans attend worship services each week (Hadaway and Marler 2005). It is unclear whether individuals with schizophrenia have more or less contact with their place of worship than the general public, but given the social isolation that is often associated with this disease, it is possible that the 39% of respondents who disclose their diagnosis in places of worship may represent a large majority of all respondents who attend services regularly or have significant social contact with others in that setting.

The relatively low rates of being treated worse in places of worship (18%) compares favorably to healthcare settings where 24% report being treated worse. A disturbingly large percentage of respondents report that they have greater difficulty getting treatment for their medical problems and that doctors who know their schizophrenia diagnosis are perceived as regarding their medical problems less seriously. This finding suggests that biased treatment may play a role in the 60% of premature deaths in people with schizophrenia that are due to medical conditions as described in a recent review (NASMHPD 2006). In that report, seven factors are identified as causes for this greater mortality, including factors related to medications, systems issues and the effects of psychiatric symptoms. Our study suggests that another factor, specific to an awareness of the diagnosis may affect the quality of medical care provided to those with schizophrenia. Prior studies show that mental health professionals hold stigmatizing beliefs (Nordt et al. 2006) and that other specialties may have greater rates of stigmatizing beliefs (Bjorkman et al. 2008; Chin and Balon 2006). Taken together with the results of this study, stigma by healthcare providers must be strongly suspected of playing a role in the premature mortality of individuals with schizophrenia. Because healthcare professionals are taught that schizophrenia is a disease, our findings of healthcare bias supports a prior study that questions the effectiveness of anti-stigma campaigns based on education about biological etiologies (Angermeyer and Matschinger 2005). However, since healthcare professionals are also routinely exposed (at least briefly) to individuals with schizophrenia during training, this finding also challenges a study that suggests stigma is more directly related to a lack of familiarity (Corrigan et al. 2001). The experience of stigma in healthcare settings also provides an interesting perspective on the proposal that stigma is based on conceptions of treatability (Angermeyer and Matschinger 2005) or dangerousness (Angermeyer and Matschinger 2005; Link et al. 1999b). Individuals in healthcare settings should have better than average knowledge about the actual data on treatability and violence associated with schizophrenia. Future research should assess whether healthcare providers are, in fact, knowledgeable about treatability and the risk of violence, and whether variation in perceived treatability and perceived risk accounts for the perceived prejudicial medical treatment reported in this study. If stigma is dependent on beliefs about treatability and risk of violence and if our findings are verified by subsequent studies, the prejudicial treatment in healthcare settings bodes poorly for public education campaigns as it is suggests that in order to combat stigma we would need to provide more education than is currently provided to professional healthcare workers.

This study also suggests the importance of gender in the doctor-patient relationship for individuals with schizophrenia. Women were statistically more likely to report being treated worse by doctors who know of their schizophrenia diagnosis and a larger percentage of women reported that their medical problems were taken less seriously and that it was harder to get access to physical health care when their diagnosis of schizophrenia was known. Prior studies suggest that women may receive less aggressive medical care compared to men (Gan et al. 2000; Wexler et al. 2005) and this study suggests that women with schizophrenia may be a doubly vulnerable population.

More broadly, the very different groups in this study suggest that a unitary approach to stigma may be an oversimplification. More than twice as many subjects report getting treated worse by police/correctional officers than by people at their place of worship. Thus, interventions in law enforcement settings such as Crisis Intervention Teams may have a far greater impact on the negative experiences of individuals with schizophrenia than interventions with other groups. By contrast, in places of worship, education may shift from a focus on tolerance to a focus on how to create a welcoming environment where individuals with schizophrenia may be more inclined to share their personal struggles with this disease.

The characteristics of our sample may limit the generalizability of our results. Caucasians are overrepresented in our sample and prior studies suggest that minorities may differ from Caucasians in the dynamics of family caregiving (Magaña et al. 2007) and in stigmatizing beliefs (Anglin et al. 2006). Future studies could benefit from greater attention to the experience of ethnic and racial minorities. More importantly, this sample all self-identified as having schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and therefore may not be representative of the many individuals who do not have this level of insight. The sample was recruited through NAMI, an organization that provides a broad range of education and which engages in advocacy. Thus, individuals may be sensitized to the issues of stigma through NAMI’s education programs. Also, individuals with more negative experiences around their disease may be more prone to be involved with NAMI. The convenience sample obtained through an online survey is also skewed towards those with access to a computer and those who are comfortable using this technology. However, it is important to recognize that there are limitations to any other single source of data collection on this subject. If this survey was conducted through live interviews, individuals with more negative symptoms and individuals with greater shame around their disease may be less inclined to participate. In addition, live interviews of individuals in treatment centers, clubhouses or residential settings would each skew the sample in different ways (ex., towards individuals who are getting active treatment, towards individuals who are more socially engaged or towards individuals that are less able to live independently). If this survey was done via paper and the mail, the increment in motivation necessary to return such surveys would risk a bias towards individuals with more profound negative experiences and less profound negative symptoms. In the experience of the authors through their work on a variety of projects with NAMI, our members with serious mental illness are often more able and willing to use the internet than many of our other members. Finally, because this is a secondary analysis of a dataset, the findings should be further tested using this study to generate primary hypotheses.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Carol Tamminga, M.D., Charles Schulz, M.D., Stephen Goldfinger, M.D., Loren Booda, Elizabeth Edgar, Lisa Halpern, Laudan Aron, Bob Carolla, J.D., Christine Lehman, and Harris Interactive. This project was made possible with support from AstraZeneca, Solvay, and Wyeth.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Causal beliefs and attitudes to people with schizophrenia: Trend analysis based on data from two population surveys in Germany. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186(4):331–334. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglin DM, Link BG, Phelan JC. Racial differences in stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:857–862. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman T, Angelman T, Jonsson M. Attitudes towards people with mental illness: A cross-sectional study among nursing staff in psychiatric and somatic care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2008;22(2):170–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin SH, Balon R. Attitudes and perceptions toward depression and schizophrenia among residents in different medical specialties. Academic Psychiatry. 2006;30:262–263. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.30.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Green A, Lundin R, Kubiak MA, Penn DL. Familiarity with and social distance from people who have serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(7):953–958. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB, Sommerville J, Origoni AE, Ringel NB, Parente F. Experiences of stigma among outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2002;28(1):143–155. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertugrul A, Ulug B. Perception of stigma among patients with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004;39:73–77. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan SC, Beaver SK, Houck PM, MacLehose RF, Lawson HW, Chan L. Treatment of acute myocardial infarction and 30-day mortality among women and men. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343(1):8–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007063430102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadaway CK, Marler PL. How many americans attend worship each week? An alternative approach to measurement. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2005;44(3):307–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2005.00288.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee MTY, Chiu MYL, Kleinman A. Experience of social stigma by people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:153–157. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: Labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1328–1333. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: Labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1328–1333. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC. The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(12):1621–1626. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña SM, García JIR, Hernández MG, Cortez R. Psychological distress among latino family caregivers of adults with schizophrenia: The roles of burden and stigma. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(3):378–384. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.3.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr S, Brandt P-Y, Borras L, Gilliéron C, Huguelet P. Toward an integration of spirituality and religiousness into the psychosocial dimension of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1952–1959. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.11.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakane, Y., Jorm, A. F., Yoshioka, K., Christensen, H., Nakane, H., & Griffiths, K. M. (2005). Public beliefs about causes and risk factors for mental disorders: a comparison of Japan and Australia. Journal, 5(33). Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/5/33. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- NASMHPD . Morbidity and mortality in people with serious mental illness. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nordt C, Rossler W, Lauber C. Attitudes of mental health professionals toward people with schizophrenia and major depression. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(4):709–714. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N, Leese M, For the INDIGO Study Group Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2009;373:408–415. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl OF. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999;25(3):467–478. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler DJ, Grant RW, Meigs JB, Nathan DM, Cagliero E. Sex disparities in treatment of cardiac risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(3):514–520. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos PT, Roe D, Markus K, Lysaker PH. Pathways between internalized stigma and outcomes related to recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(12):1437–1442. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]