Abstract

Tyrosine and glycine constitute 40% of complementarity determining region 3 of the immunoglobulin heavy chain (CDR-H3), the center of the classic antigen-binding site. To assess the role of DH RF1-encoded tyrosine and glycine in regulating CDR-H3 content and potentially influencing B cell function, we created mice limited to a single DH encoding asparagine, histidine, and arginines in RF1. Tyrosine and glycine content in CDR-H3 was halved. Bone marrow and spleen mature B cell and peritoneal cavity B-1 cell numbers were also halved, whereas marginal zone B cell numbers increased. Serum immunoglobulin G subclass levels and antibody titers to T-dependent and T-independent antigens all declined. Thus, violation of the conserved preference for tyrosine and glycine in DH RF1 alters CDR-H3 content and impairs B cell development and antibody production.

Unlike H chain complementarity determining regions 1 and 2, which are entirely encoded by the VH gene segment, CDR-H3 is created de novo by the VDJ rearrangement process (1–3). Imprecision in joining these gene segments permits exonucleolytic loss as well as palindromic (P junction) gain of terminal VH, DH, and JH sequence. The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) catalyzed insertion of N nucleotides at the sites of joining permits the inclusion of nongermline sequence into CDR-H3 (1, 2). Together, these mechanisms create a CDR-H3 repertoire that ranges from unmodified and intact germline-encoded sequence to rearrangements where extensive nibbling and N addition no longer permit identification of the original DH. The extensive range of diversity available to CDR-H3 has functional consequences because its location at the center of the antigen-binding site, as classically defined, permits this interval to often play a significant role in antigen recognition and binding (4–6).

Flanked on both sides by 12-base spacer recombination signal sequences, each DH gives the developing B cell access to six reading frames (RFs) of distinctly different germline sequence. In practice, from shark to mouse to human, sequences encoded by RF1 generated by deletion dominate the mature B cell repertoire (7, 8). RF1 is typically enriched for tyrosine and glycine codons. Together, these two neutral amino acids contribute ∼40% of the amino acids in the CDR-H3 loop (8, 9).

To test the role of germline RF1 sequence in determining CDR-H3 amino acid usage and to test whether a mouse starting with altered germline sequence could recreate a wild-type CDR-H3 repertoire by somatic means, we replaced central codons for RF1-encoded tyrosine and glycine in DFL16.1, the most JH-distal DH, with codons for arginine, histidine, and asparagine and deleted the intervening DH. We found that B lineage cells in the bone marrow of these mice maintained their preference for RF1 through the mature, recirculating IgM+IgD+ B cell stage of development. As a result, usage of arginine, asparagine, and histidine content in mature CDR-H3 loops tripled, whereas tyrosine and glycine content was reduced by one half.

This change in CDR-H3 amino acid content had functional consequences. Homozygous mutant mice exhibited a consistent reduction in total B cell numbers, a redistribution of peripheral B cell subsets, and a decrease in total and antigen-specific antibody levels. These findings confirm the power of the mechanisms used to regulate RF usage (7, 9, 10) and demonstrate a significant role for the DH gene segment in controlling CDR-H3 amino acid composition. They illustrate the importance of CDR-H3 amino acid content in B cell development and antibody production.

RESULTS

Generation of the ΔD-iD mouse

We replaced the central portion of DFL16.1, the most VH-proximal DH (11), with the complete inverted coding sequence of DSP2.2 (Fig. 1). This allowed us to replace central RF1 codons for tyrosine and glycine with those for arginine, histidine, and asparagine. We termed this hybrid DFL16.1-inverted DSP2.2 D element iD for inverted D. DFL16.1 sequence encoding tyrosine and serine at the 5′ and 3′ termini of the DH gene segment was retained to preserve microhomology between the 3′ end of the DH and the 5′ end of JH (9, 10). iD RF1 generated by inversion (i-RF1) encompasses the original tyrosine enriched sequence of DSP2.2 RF1. iD RF2 and RF3 by deletion and RF1 and RF3 generated by inversion (i-RF2 and i-RF3) maintain a preference for hydrophobic amino acids, and RF3 and i-RF3 continue to incorporate termination codons. We used gene targeting via homologous recombination in a BALB/c embryonic stem cell line (12) to create an IgH allele (depleted DH locus with a single, mutated DFL16.1 gene segment containing inverted DSP 2.2 sequence [ΔD-iD]) limited to this single, modified DH.

Figure 1.

Generation of a single DH-containing IgH locus by use of the Cre-loxP system. (A) Illustration of the DH locus. Wild-type (WT), the locus after targeted replacement of DQ52 and DFL16.1 (iD), and the locus after Cre-mediated deletion leaving the single iD gene juxtaposed to the JH locus (ΔD-iD) are shown. V and C denote the full set of germline variable gene segments and constant region exons, respectively. (B) The sequence of iD. DSP2.2 has been embedded within DFL16.1 in an inverted orientation (in red). The average hydrophobicity is noted in parentheses. (C) Generation of the ΔD-iD allele. Southern blot analysis of tail DNA from wild-type (wt/wt), heterozygous iD (iD/wt), and heterozygous DH locus deleted iD (ΔD-iD) mice. (D) The DH RF1 sequences of the wt and ΔD-iD DH alleles. The mutant DH locus has lost the neutral, hydrophilic amino acids present at the center of the 13 WT DH gene segments, but has gained the positively charged amino acids present in iD. The interval corresponding to the region replaced by the inverted DSP 2.2 gene segment is outlined in yellow.

Amino acid utilization in ΔD-iD/ΔD-iD mature B cells reflects dominant use of iD RF1

We sorted bone marrow B lineage cells on the basis of surface expression of CD19, CD43, IgM, BP-1, and IgD (13, 14) (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20052217/DC1), isolated total RNA, performed RT-PCR using primers specific for Cμ and the VH7183 family as representative of the repertoire as a whole, and performed detailed sequence analyses of the expressed repertoire as described previously (12, 14).

We found no evidence of selection during development for use of DH RFs that lacked arginine, histidine, and asparagine. In fraction B CD19+CD43+BP-1−IgM− progenitor B cells, 74% of the sequences used RF1 and, in fraction F CD19+CD43−IgM+IgD+ mature, recirculating B cells, 80% used the mutant RF1 (Fig. S2, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20052217/DC1). Although DH inversions were more frequent in ΔD-iD B cells than in the wild-type or depleted DH locus with single DFL16.1 gene segment (ΔD-DFL) controls, their prevalence did not increase with development even though iD i-RF1 recapitulates the normally preferred tyrosine-enriched sequence of DSP2.2 RF1. Among the 326 iD-containing CDR-H3 sequences, four contained iD sequences in i-RF1 and seven used i-RF2 (Tables S1 and S2, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20052217/DC1). The prevalence in fraction B progenitor B cells of inverted sequences was equivalent to fraction F mature, recirculating B cells (4 out of 71 vs. 4 out of 76, respectively) (Fig. S2). Of 225 DFL16.1-containing sequences from the ΔD-DFL mice and the 902 wild-type sequences containing an identifiable DH, none contained a DH inversion (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively).

We found no evidence of selection for sequences that had undergone extensive exonucleolytic loss at the termini of the iD gene segment (Fig. 2). The germline contribution of the iD gene segment remained virtually unchanged between fraction B progenitor B cells and fraction F mature, recirculating B cells with 95% of the CDR-H3 intervals containing identifiable iD sequence in each. To control for the effect of eliminating 12 out of the 13 DH gene segments in the DH locus, we compared this pattern of DH retention to that previously observed in ΔD-DFL mice, which are D-limited to a single DFL16.1 gene segment (12), and found it to be equivalent (P = 0.23). We did observe an increase in the contribution of 5′ terminal JH sequence with development, but this paralleled the pattern we had previously observed in WT mice (14).

Figure 2.

Deconstruction of CDR-H3 sequences containing the mutated iD DH gene segment during progressive stages in B cell development. (top) The potential contribution of the germline sequence of the VH gene segment, the iD DH gene segment, and the four JH gene segments to CDR-H3 length is illustrated. (bottom) The actual contribution of these components to 70 fraction B, 49 fraction C, 60 fraction D, 76 fraction E, and 71 fraction F sequences. All components are shown to scale. N addition at the D→J junction decreases from fraction C to D (P < 0.02). JH sequence contribution increases from fraction B to E (P < 0.05). Other differences did not achieve statistical significance.

We found no evidence of selection for increased N nucleotide content with development (Fig. 2). We did observe a decrease in the average number of N nucleotides inserted between D and J between fraction C CD19+CD43+BP- 1+IgM− early pre–B cells and fraction D CD19+CD43−IgM−IgD− late pre–B cells. However, this pattern contradicts the expected result if there was selection for N nucleotide–encoded amino acids in response to surrogate light chain-associated selection pressures.

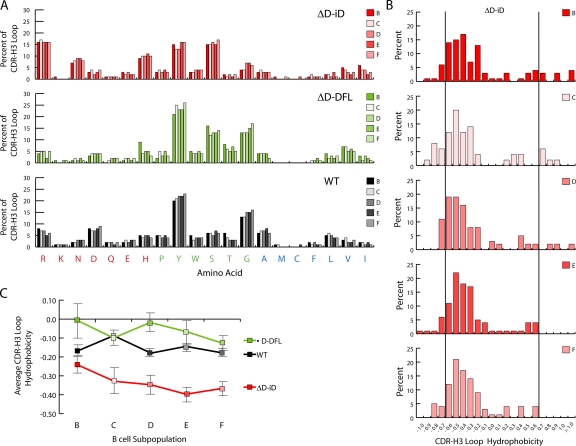

The stability of exonucleolytic loss and N region gain created CDR-H3 repertoires whose average length remained unchanged during development (Fig. 2 and Fig. S3, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem. 20052217/DC1). The preservation of iD sequence contributed to a predominance of arginine, asparagine, and histidine at all stages of bone marrow repertoire development examined (Fig. 3 A). Together, these amino acids comprised approximately one third of the amino acids in the CDR-H3 loop, tripling their contribution to the repertoire when compared with controls (P < 0.001). Conversely, the contribution of tyrosine and glycine to the loop was halved (P < 0.001). Persistence of the charged amino acids was associated with enrichment for CDR-H3 loops with an average normalized Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity value of less than −0.700 (Fig. 3 B and Table S3, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20052217/DC1).

Figure 3.

Amino acid usage and average hydrophobicity profiles for CDR-H3 sequences containing the mutated iD DH gene segment during progressive stages in B cell development. (A) Distribution of individual amino acids in the CDR-H3 loop of sequences from homozygous ΔD-iD, ΔD-DFL, and wild-type (WT) mice as a function of B cell development according to Hardy et al. (reference 13). The distributions are calculated through analysis of 9,322 individual amino acids from 342 unique ΔD-iD CDR-H3 loops, 3,710 amino acids from 242 unique ΔD-DFL CDR-H3 loops, and 17,583 amino acids from 1,074 unique WT CDR-H3 loops. (B) Distribution of average CDR-H3 hydrophobicities in V7183DJCμ transcripts from homozygous ΔD-iD mice in Hardy B-lineage bone marrow fractions B through F (reference 13). The normalized Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity scale (reference 49) has been used to calculate average hydrophobicity. Although this scale ranges from −1.3 to +1.7, only the range from −1.0 (charged) to +1.0 (hydrophobic) is shown. Prevalence is reported as the percent of the sequenced population of unique, in-frame, open transcripts from each B lineage fraction. To facilitate visualization of the change in variance of the distribution, the vertical lines mark the preferred range average hydrophobicity previously observed in WT fraction F (reference 14). The number of unique V7183DJCμ sequences analyzed is shown for each developmental B cell subset. Among the ΔD-iD sequences with loops, there are 172 sequences in fractions B, C, and D in the normal and charged range, and 10 sequences with an average hydrophobicity >0.600. There are 158 sequences in fractions E and F in the normal and highly charged range (≤0.700), but none in the highly hydrophobic range (≥0.700) (P < 0.01, χ2). The number of sequences in each fraction is shown. (C) Average hydrophobicity and standard error of mean of CDR-H3 intervals from VH 7183 DJCμ transcripts from homozygous ΔD-iD, ΔD-DFL, and WT mice in Hardy B-lineage bone marrow fractions B through F.

Although highly charged CDR-H3 loops were retained in the mature ΔD-iD B cell repertoire, highly hydrophobic sequences followed the normal pattern of loss during development (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4 B and Table S4, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20052217/DC1) (12,14). The selective loss of these highly hydrophobic intervals in ΔD-iD shifted the average hydrophobicity of the CDR-H3 repertoire firmly into the charged range (Fig. 4 C).

Figure 4.

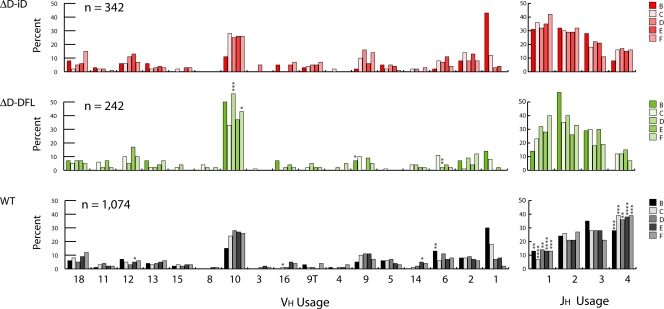

VH 7183 and JH gene segment use during B cell development. VH 7183 and JH use is reported as the percent of the sequenced population of unique, in-frame, open transcripts for Hardy fractions B (left) through F (right) according to the scheme of Hardy et al. (reference 13). Both VH and JH segments are arranged in germline order. The number of sequences analyzed is shown. (top) VH 7183 and JH use in homozygous ΔD-iD mice (ΔD-iD). (middle) VH 7183 and JH use in homozygous ΔD-DFL mice (ΔD-DFL). (bottom) VH 7183 and JH use in wild-type, homozygous IgMa mice (WT). Significant differences between WT and ΔD-iD are labeled with asterisks (**, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001 etc.; χ2).

Use of VH7183 and JH gene segments is minimally affected by the change in CDR-H3 sequence

The global effect of the shift in CDR-H3 hydrophobicity could have been ameliorated by a shift in VH or JH utilization, but we found no evidence that this had occurred either. As a population, VH7183 usage in ΔD-iD B lineage cells proved highly similar to controls (Fig. 4). JH utilization in ΔD-iD during development differed from WT in that JH4 usage was diminished and JH1 usage was enhanced; however, this usage pattern matched that previously observed in ΔD-DFL (12, 14).

Forced use of a DH containing charged sequence impairs B cell production

When compared with WT littermate controls, ΔD-iD mice exhibited a consistent reduction in total B cell numbers. The absolute numbers of CD19+ cells in the bone marrow, spleen, and peritoneal cavity of homozygous ΔD-iD BALB/c mice (Table I ) were two thirds of that observed in WT littermate controls (P = 0.004, P < 0.0001, and P = 0.001, respectively). The ratio of Igκ- to Igλ-bearing cells in ΔD-iD B cells was similar to WT littermate controls (unpublished data).

Table I.

Cell numbers in bone marrow and spleen of normal and mutant mice

| Fraction |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | N ≥ | Total cells x 106a | CD19+ x 106 | B x 105 | C x 105 | D x 105 | E x 105 | F x 105 |

| WT | 9 | 12.9 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.3) | 19.0 (1.4) | 7.1 (0.4) | 3.9 (0.5) |

| ΔD-iD | 12 | 11.6 (0.4)b | 2.1 (0.2)d | 4.3 (0.6)b | 2.1 (0.3) | 13.6 (1.2)c | 4.9 (0.5)b | 1.9 (0.3)d |

| Spleen | Total cells x 106 | CD19 + x 106 | T1 x 105 | T2 x 105 | T3 x 105 | MZ x 105 | M x 105 | |

| WT | 8 | 53.9 (3.3) | 22.5 (1.0) | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | 14.5 (1.4) |

| ΔD-iD | 10 | 42.3 (1.7)d | 14.3 (0.6)e | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.0) | 1.2 (0.1)e | 1.9 (0.2)b | 7.8 (0.5)e |

| Peritoneal cavity | Total cells x 105 | CD19 + x 105 | B1a x 105 | B1b x 105 | B2 x 105 | |||

| WT | 10 | 31.0 (3.2) | 11.5 (0.7) | 4.2 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.3) | ||

| ΔD-iD | 10 | 23.7 (1.4)d | 7.8 (0.6)e | 1.9 (0.6)e | 1.0 (0.1) | 2.8 (0.3) | ||

Total nucleated cells that excluded trypan blue. In the bone marrow, values shown are cell counts per femur (average cellularity of two femurs collected from each experimental animal) of paired 8-wk-old homozygous ΔD-iD (ΔD-iD) or homozygous wild-type (WT) littermate progeny of heterozygous ΔD-iD/WT BALB/c mice. The standard error of the mean is shown in parentheses. The number of cells in fractions B (CD19+CD43+HSA+BP-1−), C (CD19+CD43+HSA+BP-1+), D (CD19+CD43−IgM−IgD−), E (CD19+CD43−IgM+IgD−), and F (CD19+CD43−IgMloIgDhi) was determined from the relative proportion of total cells. Cell counts per spleen of 8-wk-old homozygous ΔD-iD or wt littermate progeny of WT BALB/c mice. In the spleen, transitional T1 (CD19+AA4.1+sIgMhiCD23−), T2 (CD19+AA4.1+sIgMhiCD23+), and T3 (CD19+AA4.1+sIgMintCD23+) splenic B cell subsets were determined as described by Allman et al. (reference 46). Marginal zone (MZ, CD19+CD21hiCD23lo) and mature (M, CD19+CD21loCD23hi) B cell subsets were determined as described by Oliver et al. (reference 47). In the peritoneal cavity, values shown are average cell counts per single peritoneal lavage of 8-wk-old homozygous ΔD-iD or WT littermates. The number of B1a (CD19+CD5+), B1b (CD19+Mac-1+CD5−), and B2 (CD19+Mac-1−CD5−) cells were determined from the relative proportion of total cells.

P ≤ 0.05.

P ≤ 0.01.

P ≤ 0.005.

P ≤ 0.001 versus BALB/c wild-type littermates.

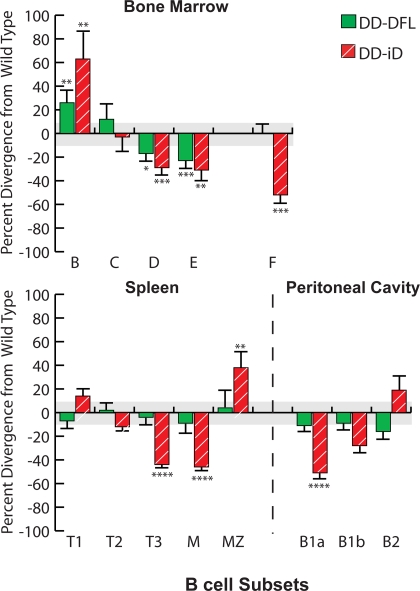

Although total B cell numbers were decreased, some individual B cell subsets exhibited normal numbers and others demonstrated increases (Table I). The average numbers of CD19+CD43+IgM−BP-1− fraction B cells, primarily pro–B cells, were higher than littermate controls (P = 0.05). The numbers of CD19+CD43+IgM−BP-1+ fraction C cells, primarily early pre–B cells, were essentially unchanged. When compared with wild-type littermate controls, the CD19+CD43−IgM−IgD− fraction D late pre–B cell and CD19+CD43−IgM+IgD− fraction E immature B cell subpopulations exhibited a 30% decrease in cell numbers (P = 0.008 and P = 0.05, respectively). This pattern of a progressive decrease in cell numbers with development in bone marrow was similar to that previously observed in ΔD-DFL mice (Fig. 2) (12).

In the spleen, the absolute numbers of cells in the transitional T1 (CD19+AA4.1+IgMhiCD23−) and T2 (CD19+AA4.1+IgMhiCD23+) subsets were similar to that in both WT and ΔD-DFL (Table I, and Fig. 5 ) (12, 14). However, when compared with controls, the absolute numbers of T3 (CD19+AA4.1+IgMloCD23+) and mature follicular (M) (CD19+CD23hiCD21lo) ΔD-iD B cells were reduced by one half (P = 0.002, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.0001, respectively), whereas T3 and mature B cell numbers were indistinguishable from WT in ΔD-DFL. In marked contrast with the decrease in the absolute numbers of mature follicular cells, the absolute numbers of CD19+CD23loCD21hi marginal zone (MZ) B cells were increased by one third (P = 0.03) in ΔD-iD.

Figure 5.

Divergence in the absolute numbers of B lineage subpopulations from the bone marrow, spleen, and peritoneal cavity of homozygous ΔD-iD and ΔD-DFL mice relative to their littermate controls. Percent loss or gain in homozygous ΔD-iD and ΔD-DFL mice relative to WT littermate controls in the average absolute number of cells in bone marrow fractions B (CD19+CD43+HSA+BP-1−), C (CD19+CD43+HSA+BP-1+), D (CD19+CD43−IgM−IgD−), E (CD19+CD43−IgM+IgD−), and F (CD19+CD43− IgMlo IgDhi); in splenic transitional T1 (CD19+AA4.1+sIgMhi-CD23−), T2 (CD19+AA4.1+sIgMhiCD23+), T3 (CD19+AA4.1+sIgMloCD23+), marginal zone (MZ, CD19+CD21hiCD23lo), and mature (M, CD19+CD21loCD23hi) B cell subsets (references 46, 47); and in peritoneal cavity B1a (CD19+CD5+), B1b (CD19+CD5−Mac-1+), and B2 (CD19+CD5−Mac-1−) (Table I and Figs. S1–S4). The standard error of the mean of each B lineage subpopulation for the littermate controls averaged ∼11% of the absolute number of cells in each subpopulation (gray area). For ΔD-iD and ΔD-DFL, the standard error of the mean is shown as an error bar. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001.

In the peritoneal cavity, the absolute numbers of B1a cells (CD19+CD5+Mac-1+) in ΔD-iD mice were one half (P < 0.0001) that of WT, and the B1b population (CD19+CD5−Mac-1+) was reduced by 25% (P = 0.06) (Table I and Fig. 5). In contrast with the reduction in mature B cell numbers in the bone marrow and spleen, the numbers of peritoneal cavity B2 cells (CD19+CD5−Mac-1−) were slightly increased (P = 0.27) when compared with controls.

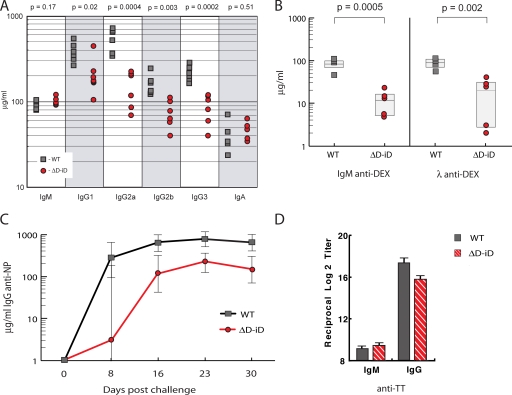

Humoral immune responses are impaired

We measured serum immunoglobulin levels in homozygous ΔD-iD and WT littermates at 8 wk of age. The geometric mean concentration of all four IgG subclasses in the sera of ΔD-iD mice was significantly less than that of WT (P = 0.02, P = 0.0004, P = 0.003, and P = 0.0002, respectively) (Fig. 6 A). The serum concentration of IgM and IgA was comparable to WT (P = 0.17 and P = 0.51, respectively).

Figure 6.

Alterations in humoral immune function in homozygous ΔD-iD mice. (A) The concentrations of IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, and IgA in the serum of six 8-wk-old homozygous ΔD-iD and six homozygous WT littermates (ELISA). The geometric mean concentration of IgM (104 μg/ml [91–118, 95% confidence limits] and IgA (47 μg/ml [34–63]) proved comparable to WT (94 μg/ml [80–109], P = 0.17; and 38 μg/ml [23–64], P = 0.51, respectively). In contrast, the geometric mean concentrations of all four IgG subclasses were significantly reduced in the mutant mice. (IgG1 201 μg/ml [122–329] vs. 382 μg/ml [267–543]; P = 0.02; IgG2a 141 μg/ml [81–245] vs. 516 μg/ml [333–799]; P = 0.0004; IgG2b 71 μg/ml [48–106] vs. 155 μg/ml [108–224], P = 0.003; and IgG3 82 μg/ml [52–130] vs. 224 μg/ml [171–293]; P = 0.0002, respectively). (B) The primary T-independent response to α-1,3 dextran (DEX) is diminished in homozygous ΔD-iD mice. The geometric mean concentrations of anti-DEX IgM and Igλ antibody titers 7 d after immunization were 10 μg/ml [4–23] vs. 79 μg/ml [43–143], and 11 μg/ml [2–63] vs. 83 μg/ml [51–134], respectively; P < 0.01). Titers in preimmune sera were <1 μg/ml; not depicted. (C) The primary T-dependent IgG response to NP19-CGG in homozygous. ΔD-iD mice is diminished when compared with WT littermates. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (D) TT-specific antibody responses in ΔD-iD mice. 24 homozygous ΔD-iD and 24 WT littermate controls were each orally immunized with 250 μl of 5 × 109 rSalmonella-ToxC. 4 wk later, plasma samples were collected and subjected to TT-specific ELISA. The data are shown as the reciprocal log2 titer. For ΔD-iD the mean IgM and IgG anti-TT titers were 9.1 ± 0.2 and 15.1 ± 0.5, respectively; whereas, for WT IgG the mean titer were 9.3.1 ± 0.2 and 17.5 ± 0.3 (P = 0.64 and P = 0.0004, respectively).

Immune responses to both T-dependent and T-independent antigens were impaired. In WT BALB/c mice, intravenous challenge with DEX elicits a T-independent response that is dominated by λ1 light chain–bearing antibodies that express a diverse range of antigen-binding sites with heterogeneous CDR-H3 sequences (15, 16). The IgM and the Igλ anti-DEX responses in homozygous ΔD-iD BALB/c mice (Fig. 6 B) were significantly lower than those in WT (P < 0.01). In BALB/c, the primary response to the nitrophenylacetyl hapten of [4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl] acetyl-chicken γ globulin (NP19-CGG) requires T cell help and contains a large fraction of IgG1λ anti-NP antibodies (17). After intraperitoneal challenge, the anti-NP IgG response in ΔD-iD mice was threefold diminished when compared with WT littermates (P < 0.03) (Fig. 6 C). In BALB/c, immunization with purified tetanus toxin (TT) elicits a T-dependent response that is dominated by κ light chain–bearing antibodies (18). After oral immunization with a recombinant strain of Salmonella that expresses the Tox C fragment of TT (19), the IgM anti-TT response in ΔD-iD mice proved equivalent to WT littermate controls, but the IgG response was approximately fourfold diminished (P = 0.0004) (Fig. 6 D). ELISA analysis using anti-κ and anti-λ reagents documented a preference for κ L chain–bearing antibodies in both the ΔD-iD and WT anti-TT response (unpublished data).

DISCUSSION

Replacement of DH RF1-encoded tyrosine and glycine with codons for arginine, histidine, and asparagine resulted in extensive substitution of the latter positively charged amino acids for the former neutral ones in the CDR-H3 repertoire. These findings document the power of the mechanisms used to regulate DH RF choice (7, 9, 10). Maintenance of the terminal coding sequence of DFL16.1 (Fig. 1) preserved the ability to undergo microhomology-directed DHRF1→JH recombination (9, 10). iD RF2 was placed in-frame with the upstream DFL16.1 ATG translation start site to permit Dμ protein production, which can invoke mechanisms of allelic exclusion (7, 9). The inclusion of termination codons in iD RF3 limited its usage. Rearrangement by deletion remained favored over inversion. Together, these mechanisms maintained the preference for use of RF1 in spite of the change in the coding sequence of the mutant DH.

These mechanisms were not an absolute blockade for the generation of alternative CDR-H3 sequence. Inversions of iD that created WT tyrosine-enriched CDR-H3 sequence were observed. N nucleotides were introduced at random, and exonucleolytic nibbling did occur to the extent that 5% of the CDR-H3 sequences did not contain identifiable iD sequence. As a result of the deletion of all but one DH gene segment, our model did not allow us to test whether selection for D-D fusions could have corrected the change in the sequence of the mutant DH. However, D-D fusion is a very rare event, and none of the 902 WT sequences with identifiable DH contained a recognizable D-D fusion using our threshold of DH identification. This suggests that D-D fusion would be unlikely to contribute “ameliorated” sequences at a higher rate than that observed for iD inversion.

Because sequences with WT characteristics generated by iD inversion or by a combination of terminal sequence loss and N addition were detected in early B cell progenitors, selection for these alternative sequences could have recreated a “WT” CDR-H3 repertoire in mature B cells. We had previously documented selection during development for a specific range of CDR-H3 lengths, amino acid content, and average hydrophobicity in both WT (14) and ΔD-DFL mice (12), thus this seemed a likely outcome in ΔD-iD. However, ΔD-iD RF1-encoded arginine, histidine, and asparagine CDR-H3 remained overrepresented at all stages of bone marrow B cell development examined, including the mature, recirculating CD19+IgM+IgD+ pool. Somatic selection did not shepherd the repertoire toward the WT range, even though the end result was a reduction in mature B cell numbers and antibody production. These data suggest that the somatic mechanisms normally used to select the repertoire can be subordinate to evolutionary conservation of germline sequence in regulating CDR-H3 content even though B cell function may suffer.

Early B cell development in the ΔD-iD mice followed a pattern similar to that observed in ΔD-DFL mice, which are limited to a single DH of normal, tyrosine- and glycine-enriched sequence (12). This pattern included an accumulation of fraction B pro–B cells, normalization of the number of fraction C early pre–B cells, and a reduction in fraction D late pre–B and fraction E immature B cell numbers. The decreased efficiency with which developing ΔD-iD B cells transit through the bone marrow appears to reflect the loss of DH locus sequence rather than the change in the sequence of the remaining DH.

A potential mechanism that could have affected early repertoire development is incomplete access or altered use of the full germline array of VH and JH gene segments. We chose VH7183 as the representative VH family because all of the family members encoded by the IgHa allele have been defined previously (20), key patterns of individual VH7183 gene segment utilization are well established (20–22), it accounts for a manageable 10% of the active repertoire (23), and VH7183 gene segments have been shown to contribute to both self- and nonself-reactivities (24, 25).

With a few limited exceptions, VH7183 gene segment use, including use of VH81X (7183.1), proved similar to WT controls at both early and late stages of development. VH usage appeared minimally affected by the central coding sequence of DH or by the global alteration of CDR-H3 loop amino acid content.

Compared with WT, JH4 usage was depressed and the use of JH1 was enhanced. This pattern matched that previously observed among ΔD-DFL sequences, suggesting that the alteration in JH usage was independent of the change in the coding sequence of the single, remaining DH (12). JH4 and, to a lesser extent, JH3 usage has been previously shown to be diminished in VDJ rearrangements from mice lacking DQ52 together with cis-regulatory sequence immediately upstream of this JH-proximal gene segment (26). Together, these data suggest that the alteration in JH usage is the result of the deletion of the remainder of the DH locus, perhaps, as previously suggested (26), as a result of a loss of the ability to engage in secondary D-J rearrangements.

Efficient transition from fraction B, primarily pro–B cells, to fraction C, early pre–B cells, is associated with successful creation of a functional H chain (13). Accumulation of pro–B cells has been observed in the context of a deletion of DFL16.1 through JH1, inclusive, in C57BL/6 mice (27) and in the context of the ΔD-DFL deletion in BALB/c (12). Preliminary analysis of hybridomas obtained from ΔD-DFL BALB/c mice has shown that the nonfunctional ΔD-DFL allele is frequently found in a germline, unrearranged state (12). Inefficiency in the initiation, progression, or completion of D→J rearrangement as a result of DH locus deletion may be the cause of the relative increase in the number of fraction B cells as well as in the alteration of JH usage.

Progression from fraction C, early pre–B cells, to fraction D, late pre–B cells, requires successful assembly of a pre–B cell receptor (28). Potential mechanisms for the decrease in the absolute number of cells in fraction D include an impaired ability to associate with surrogate light chain, as well as altered reactivity of the pre-BCR, including autoreactivity. Passage to fraction E, which contains immature B cells, then requires both in-frame light chain rearrangement and successful association of the rearranged L chain with its H chain partner (13). Fraction E cells may lose surface IgM expression during receptor editing or may be released from the bone marrow to undergo maturation in the periphery, which is associated with surface coexpression of IgD. Potential mechanisms for the decrease in the absolute numbers of cells in fraction E include failure to undergo proper L chain rearrangement, leading to (a) a block in the progression from D to E; (b) a more rapid progression from E to the transitional cell population in the periphery as a result of enhanced success of H-L partnering; or, conversely, (c) enhanced receptor editing (29) as the result of functional failure of H-L partnering, causing inflation in the numbers of cells identified as fraction D. This latter scenario seems less likely because fraction D numbers were also depressed. Formal testing of these hypotheses will require kinetic evaluation of developing B cell populations in both ΔD-DFL and ΔD-iD mice (30).

Although the initial pattern of B lineage cell production in ΔD-iD proved similar to that observed in ΔD-DFL, a striking divergence in B cell numbers was observed among the splenic follicular and MZ populations, and among recirculating B cells in the bone marrow. The decrease in numbers in the ΔD-iD T3 transitional population paralleled the reduction in mature, follicular B cells. It has been hypothesized that the antibody repertoires expressed by mature B cells in the follicles and MZ of the spleen are shaped by selection for antigen specificity (31), including negative selection of B cells bearing autoreactive antibodies (32) and positive selection in both the recirculating mature B cell pool and the MZ (31, 33–35). Highly charged CDR-H3 sequences, especially long arginine-containing CDR-H3, are thought to be more likely to generate self-reactive antibodies (36, 37); and preliminary studies indicate that IgG anti-DNA antibodies are more common in the sera of young ΔD-iD mice than WT (unpublished data). It is possible that the increase in MZ cell numbers and the decrease in follicular and recirculating mature B cell numbers reflect a redirection of ΔD-iD B cells as a consequence of altered patterns of autoreactivity. Analysis of the extent and quality of self-reactivity among ΔD-iD B cells is being actively pursued in our laboratory.

Although it remains unclear whether the T3 subset consists of precursors to the mature, follicular compartment, these data would suggest that the cells in this compartment have suffered the same selective block as that experienced by splenic mature B cells. The sequence composition of immunoglobulin CDR-H3 repertoires in the spleen is a current focus of investigation.

In the peritoneal cavity, the numbers of ΔD-iD B1a and B1b cells are reduced. This effect is most pronounced for the B1a population, which is enriched for sequences derived from perinatal progenitors that tend to be more heavily influenced by germline sequence as the result of diminished N addition (13). The ΔD-iD B2 population, which is derived from the same pool of conventional B cells that circulate through the blood and into the spleen and bone marrow (13), achieved slightly higher absolute numbers than WT. It is unclear whether this represents a compensatory increase in numbers as a result of an increase in available physiologic space or whether the altered repertoire facilitates homing into the peritoneal cavity. Kinetic studies to address this question are currently ongoing in our laboratory.

A preference for tyrosine and glycine in the CDR-H3 loop is common to jawed vertebrates (8). Tyrosine is 10-fold overrepresented in CDR-H3 repertoires when compared with protein sequence in general, and tyrosine and glycine typically provide approximately 4 out of every 10 amino acids in the CDR-H3 loop (38). Raaphorst et al. (39) have proposed that use of highly charged sequence in CDR-H3 might reduce H chain stability. By extension, charged sequence could also have adversely affected binding to surrogate light chain or L chain. Persistence of highly charged sequences through the mature B cell stage in the ΔD-iD mice described in this paper suggests that structural stability is unlikely to be the primary force driving the preservation of tyrosine and glycine in CDR-H3.

Another hypothesis to explain preference for tyrosine and glycine in CDR-H3 is that repertoires enriched for these amino acids might facilitate achievement of optimal humoral immune responses to antigen (8, 40, 41). Although homozygous ΔD-iD mice expressed normal serum concentrations of IgM and IgA, serum levels of all four IgG subclasses were reduced, indicating that the ability of homozygous ΔD-iD B cells to respond properly to a broad range of antigens might have been compromised. We tested this hypothesis by challenging the mice with DEX, a T cell–independent antigen, and with NP19-CGG (17, 42) and rSalmonella-Tox C (19, 43), both T cell–dependent antigens. After immunization, IgM titers to DEX and IgG titers to NP and TT were significantly lower than controls. Tyrosine and glycine in CDR-H3 may be required for production of efficient antigen-binding sites. Correlations between the change in CDR-H3 amino acid content to the antigen specificity or affinity of their host immunoglobulin will require in vitro production of representative antibodies followed by analysis of their structures and antigen-binding characteristics.

Our studies indicate that the sequence of DH RF1 establishes CDR-H3 amino acid usage. Somatic selection was not sufficient to recreate a “primary” repertoire enriched for tyrosine and glycine, even though B cell and antibody production was impaired. We conclude that there are limits to the power of somatic selection of the expressed repertoire that require prior selection on a genomic or evolutionary scale. Thus, it might be said that the DH locus of “diversity” gene segments can also be considered a locus of “delimiting” elements, wherein the DH gene segment serves not only to diversify but also to constrain the composition of CDR-H3 into a range more likely to yield optimal immune function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of targeted ES cells and the ΔD-iD mouse.

The RI-2 charon phage containing the BALB/c DFL16.1 locus was a gift from Y. Kurosawa (Fujita Health University, Toyoake, Japan) (7). An 800–base pair BglII fragment containing DFL16.1 was modified by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. NotI and KpnI cloning sites were inserted 50 base pairs downstream of the 3′ recombination signal sequence and the central portion of DFL16.1 was replaced by inverted DSP2.2 sequence. Creation of the iD mutant was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Additional germline sequence was added 5′ and 3′ of the modified BglII fragment, creating a targeting construct with a 4.2-kb 5′ long arm and a 0.7-kb 3′ short arm. A loxP-neo-loxP cassette was inserted into the NotI–KpnI cloning sites and an HSV-TK selection cassette was inserted into the tip of the long arm.

ESDQ52-KO, derived from WT BALB/c-I ES cells of the IgHa haplotype, had been targeted to insert a loxP site in lieu of a 240–base pair XhoI–SacI fragment containing the DQ52 gene and a putative 5′ cis-regulatory element (26). Using standard protocols (44), this cell line was transfected with AscI-linearized iD targeting vector (pHWS48). One ES clone was identified by Southern blot analysis and DNA sequencing to contain the iD gene in cis with the DQ52-deleted mutation and was injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts. Two iD chimeric males were bred to yield BALB/cJ iD mice, and then bred to BALB/cJ hCMV-cre transgenic mice to delete the DH locus. Integrity of the mutant allele was confirmed by Southern blot and DNA sequencing. Mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free barrier facility. All experiments with live mice were approved by and performed in compliance with IACUC regulations.

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting.

Single cell suspensions were prepared from the marrow of two femurs by flushing with staining buffer (PBS with 2% FBS and 0.1% NaN3). Red blood cells were removed with RBC lysing solution (1 mM KHCO3, 0.15 M NH4Cl, and 0.1 mM Na2EDTA). Mononuclear cells were washed twice and resuspended in a master-mix of staining buffer containing optimal concentrations of antibody reagents. Samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson).

A MoFlo instrument (DakoCytomation) was used for cell sorting. Cells from Hardy fractions C and D (45) were sorted from pooled bone marrow of two homozygous ΔD-iD and two WT sibling pairs (8 wk old) and then from two individual homozygous ΔD-iD mice (8–10 wk) and from two individual wt/wt mice (6–8 wk). B-lineage cells were enriched using anti-CD19 magnetic beads and AutoMACS (Miltenyi Biotec). CD19+ cells were incubated on ice with the following: FITC-conjugated monoclonal anti-Igκ (187.1) and anti-Igλ (JC5-1), monoclonal PE-anti-CD43 (S7), biotinylated anti-BP-1 (developed secondarily with streptavidin (SA)-allophycocyanin), and Alexxa-594-anti-CD19 (1D3) (gifts from J.F. Kearney and R.P. Stephan, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL). Cells within the lymphocyte gate, defined by light scatter, were sorted as fraction C (Igκ/λ−, BP-1+, CD43+) or fraction D (Igκ/λ−, BP-1+, CD43−) lymphocytes. Cells from Hardy fractions E and F (13) were prepared individually from the bone marrow of three homozygous ΔD-iD or WT mice (10 wk old) derived from two litters and sorted in two independent experiments. Antibodies used were polyclonal FITC-anti-IgM (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.), monoclonal PE–anti-IgD (11–26; Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.), and spectral red (SPRD) –anti-CD19 (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.). Cells within the lymphocyte gate were sorted as fraction E (CD19+, IgM+, IgD−) and fraction F (CD19+, IgM+, IgDhigh) lymphocytes.

For quantitative studies of B cell development, we bred large numbers of heterozygous ΔD-iD mice and simultaneously compared cohorts of 8–12 female homozygous mutants of the same age to similarly sized cohorts of their WT littermates. FACS studies were performed over a 3–4-d period. Bone marrow B cell subsets were characterized as described in the previous paragraph (Fig. S1). In the spleen, transitional T1, T2, and T3 subsets were differentiated by the surface expression of CD19, AA4.1, IgM, and CD23 (46) (Fig. S4, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20052217/DC1); and MZ and mature B cell populations were determined on the basis of surface expression of CD19, CD21 and CD23 (47) (Fig. S5, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20052217/DC1). In the peritoneal cavity; B1a, B1b, and B2 populations were identified on the basis of surface expression of CD19, CD5, and Mac-1 (13) (Fig. S6, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20052217/DC1).

Figs. S1–S4 give representative FACS profiles for phenotypic differentiation of B lineage, bone marrow, spleen, and peritoneal cavity cells in homozygous ΔD-iD and WT mice.

RNA, RT-PCR, cloning, and sequencing.

Total RNA was prepared from 1–2 × 104 cells of each individual Hardy fraction, sorted directly into RLT lysing buffer, using the QIAGEN RNeasy mini-kit. 30% of the total RNA preparation was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA that was primed with primer Cμ1 (5′-GACAGGGGGCTCTCG-3′) using AMV reverse transcriptase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) at 42°C for 1 h. 15% of the cDNA was used to amplify V(D)JCμ joints using the QIAGEN Taq PCR Core Kit and the manufacturer's recommended protocol under the following conditions: 95°C denaturation for 2 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min; and a final 72°C extension for 10 min. The reaction buffer contained 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 15 mM MgCl2, and 750 mM KCl. Primers used were AF303 (5′-GGGGCTCGAGGAGTCTGGGGGA-3′), specific for framework 1 of the VH7183 family (20), and the Cμ exon 1 primer Cμ2 (5′-CAGGATCCGAGGGGGAAGACATTTGG-3′). PCR products were cloned (TOPO-TA Cloning Kit; Invitrogen) and sequenced using the primer Cμ2 and Big Dye chemistry (ABI 377; Applied Biosystems).

Immunizations.

To determine basal levels of immunoglobulin isotypes in unimmunized 8-wk-old ΔD-iD and WT littermates, class-specific unlabeled and alkaline-phosphatase (AP)–labeled antibodies were used (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.).

For the DEX response, homozygous ΔD-iD and WT littermates (9–12 wk) were immunized intravenously with 100 μg of Dextran B-1355S in saline (a gift from J.F. Kearney) and bled 7 d later. For the NP-CGG response (45), homozygous ΔD-iD and WT littermates (16 wk) were immunized intraperitoneally with 10 μg of NP19-CGG (gift from T.I. Novobrantseva, Center for Blood Research, Boston, MA) precipitated in potassium aluminum sulfate (alum) in saline. Mice were bled from tail veins weekly.

Quantitative anti-DEX and anti-NP ELISA assays were performed using DEX- and NP-BSA (gifts from J.F. Kearney) as antigens coated at 25 μg/ml PBS onto CoStar EIA/RIA plates. Assays of IgM anti-DEX sera were performed as described previously using MOPC 104E as a standard (48). Assays of anti-NP sera were performed using class-specific control monoclonal antibodies B1-8 and 17.2.25. After overnight 4°C incubation with serum samples and isotype-matched antibody standards, plates were blocked and incubated with AP-labeled goat anti–mouse IgM, IgG, or Igλ as required (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.); plates were developed using p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma-Aldrich). For all ELISAs, twofold serial dilutions of individual serum samples were made in 1% BSA in PBS, and all ELISAs were read at 405 nm using a Benchmark microplate reader and software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

To compare TT-specific antibody responses between ΔD-iD and WT littermate controls, a recombinant Salmonella typhimurium BRD 847 (aroA − , aroD − ) expressing the Tox C fragment of TT (rSalmonella-Tox C) was used (19). Cohorts of 24 mice were given a primary oral dose of 5 × 109 rSalmonella-Tox C at day 0. Plasma samples were collected at day 28 for the analysis of TT-specific IgG antibodies by ELISA. Falcon microtest assay plates (Becton Dickinson) were coated with an optimal concentration of TT (100 μl of 5 μg/ml) in PBS overnight at 4°C. Twofold serial dilutions of samples were added after blocking with PBS containing 1% BSA. To detect antigen-specific antibody levels, horseradish peroxidase–conjugated, goat anti–mouse μ and γ heavy chain-specific antibodies were used (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.). In some experiments, goat anti–mouse κ or λ Abs were used as detection antibodies. Endpoint titers were expressed as the last dilution yielding an optical density at 414 nm (OD414) of >0.1 U above negative control values after 15 min incubation (19, 43).

Sequence analysis of CDR-H3.

Gene segments were assigned according to published germline sequences for the IgH gene segments as listed in the ImMunoGeneTics database (http://imgt.cines.fr:8104). The CDR3 of the immunoglobulin heavy chain was defined to include those residues located between the conserved cysteine (C92) of FR3 and the conserved tryptophan (W103) of FR4. Average hydrophobicity of CDR-H3 was calculated as described previously (13). The sequences reported in this paper have been placed in the GenBank database (accession nos. AY205614-AY205988 and DQ226217-DQ226509).

Statistical analysis.

Population means (flow cytometry, sequence data, and ELISA) were analyzed using an unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test for populations that were normally distributed and with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney for those that were not. Titers against antigen are reported as the geometric mean and 95% confidence intervals. Frequencies within a population (sequence data) were analyzed using a two-tailed Fisher's exact test. The overall frequencies of amino acids within groups of sequences were studied using a χ2 test with 19 degrees of freedom. For frequencies of individual amino acids, a χ2 test was performed. Analysis was performed with JMP IN version 5.1 (SAS Institute, Inc.). Means are accompanied by the standard error of the mean.

Online supplemental material.

Figs. S1 and S4–S6 illustrate representative flow cytometric gates and analyses of bone marrow, spleen, and peritoneal B-lineage cells from homozygous ΔD-iD and WT littermates. Fig. S2 documents DH RF usage during B cell development. Fig. S3 presents the average length of CDR-H3 in VH7183DJCμ transcripts from homozygous ΔD-iD, ΔD-DFL, and WT mice in bone marrow B-lineage subsets. Table S1 lists the nucleotide sequences of CDR-H3 from homozygous ΔD-iD mice that contain an inverted DH gene segment. Table S2 presents the predicted amino acids sequences of CDR-H3 that contain an inverted DH gene segment. Table S3 presents the predicted amino acid sequences of CDR-H3 whose average Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity is less than −0.700. Table S4 presents the Predicted amino acid sequences of CDR-H3 with average Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity greater than +0.700. Also included in the supplemental material is an Excel spreadsheet containing the deconstructed nucleotide sequences of the CDR-H3 from homozygous ΔD-iD and littermate control bone marrow B-lineage cells. All online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20052217/DC1.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank T. Buch, P. Burrows, M. Cooper, A. Egert, J. Kearney, M. Kraus, F. Martin, R. Rickert, S. Sheikh, R. Stephan, A. Szalai, and A. Tarakhovsky for their invaluable advice and support. The authors are grateful to M. Hellinger, L. Zhang, and Y. Zhuang for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grant nos. AI07051, AI42732, AI48115, HD043327, TW02130; Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung grant no. FLF1071857; and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant no. SFB/TR22 TPA17.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: ΔD-DFL, depleted DH locus with single DFL16.1 gene segment; ΔD-iD, depleted DH locus with a single, mutated DFL16.1 gene segment containing inverted DSP 2.2 sequence; CDR-H3, complementarity determining region 3 of the immunoglobulin heavy chain; DEX, α(1→3)-dextran; i-RF, inverted DH reading frame; NP19-CGG, [4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl] acetyl-chicken γ globulin; RF, reading frame; TT, tetanus toxin.

References

- 1.Tonegawa, S. 1983. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature. 302:575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alt, F.W., and D. Baltimore. 1982. Joining of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene segments: implications from a chromosome with evidence of three D-J heavy fusions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 79:4118–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajewsky, K. 1996. Clonal selection and learning in the antibody system. Nature. 381:751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kabat, E.A., T.T. Wu, H.M. Perry, K.S. Gottesman, and C. Foeller. 1991. Sequences of proteins of immunological interest. U.S.Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, Maryland. 2387 pp.

- 5.Padlan, E.A. 1994. Anatomy of the antibody molecule. Mol. Immunol. 31:169–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu, J.L., and M.M. Davis. 2000. Diversity in the CDR3 region of V(H) is sufficient for most antibody specificities. Immunity. 13:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ichihara, Y., H. Hayashida, S. Miyazawa, and Y. Kurosawa. 1989. Only DFL16, DSP2, and DQ52 gene families exist in mouse immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity gene loci, of which DFL16 and DSP2 originate from the same primordial DH gene. Eur. J. Immunol. 19:1849–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivanov, I.I., J.M. Link, G.C. Ippolito, and H.W. Schroeder Jr. 2002. Constraints on hydropathicity and sequence composition of HCDR3 are conserved across evolution. In The Antibodies. M. Zanetti and J.D. Capra, editors. Taylor and Francis Group, London. 43–67.

- 9.Gu, H., I. Forster, and K. Rajewsky. 1990. Sequence homologies, N sequence insertion and JH gene utilization in VH-D-JH joining: implications for the joining mechanism and the ontogenetic timing of Ly1 B cell and B-CLL progenitor generation. EMBO J. 9:2133–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feeney, A.J., S.H. Clarke, and D.E. Mosier. 1988. Specific H chain junctional diversity may be required for non-T15 antibodies to bind phosphorylcholine. J. Immunol. 141:1267–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurosawa, Y., and S. Tonegawa. 1982. Organization, structure, and assembly of immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity DNA segments. J. Exp. Med. 155:201–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schelonka, R.L., I.I. Ivanov, D. Jung, G.C. Ippolito, L. Nitschke, Y. Zhuang, G.L. Gartland, J. Pelkonen, F.W. Alt, K. Rajewsky, and H.W. Schroeder Jr. 2005. A single DH gene segment is sufficient for B cell development and immune function. J. Immunol. 175:6624–6632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy, R.R., and K. Hayakawa. 2001. B cell development pathways. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:595–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivanov, I.I., R.L. Schelonka, Y. Zhuang, G.L. Gartland, M. Zemlin, and H.W. Schroeder Jr. 2005. Development of the expressed immunoglobulin CDR-H3 repertoire is marked by focusing of constraints in length, amino acid utilization, and charge that are first established in early B cell progenitors. J. Immunol. 174:7773–7780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blomberg, B., W.R. Geckeler, and M. Weigert. 1972. Genetics of the antibody response to dextran in mice. Science. 177:178–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stohrer, R., and J.F. Kearney. 1983. Fine idiotype analysis of B cell precursors in the T-dependent and T-independent responses to α1-3 dextran in BALB/c mice. J. Exp. Med. 158:2081–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imanishi-Kari, T., E. Rajnavolgyi, T. Takemori, R.S. Jack, and K. Rajewsky. 1979. The effect of light chain gene expression on the inheritance of an idiotype associated with primary anti-(4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl(NP) antibodies. Eur. J. Immunol. 9:324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volk, W.A., B. Bizzini, R.M. Snyder, E. Bernhard, and R.R. Wagner. 1984. Neutralization of tetanus toxin by distinct monoclonal antibodies binding to multiple epitopes on the toxin molecule. Infect. Immun. 45:604–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.VanCott, J.L., H.F. Staats, D.W. Pascual, M. Roberts, S.N. Chatfield, M. Yamamoto, M. Coste, P.B. Carter, H. Kiyono, and J.R. McGhee. 1996. Regulation of mucosal and systemic antibody responses by T helper cell subsets, macrophages, and derived cytokines following oral immunization with live recombinant Salmonella. J. Immunol. 156:1504–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams, G.S., A. Martinez, A. Montalbano, A. Tang, A. Mauhar, K.M. Ogwaro, D. Merz, C. Chevillard, R. Riblet, and A.J. Feeney. 2001. Unequal VH gene rearrangement frequency within the large VH7183 gene family is not due to recombination signal sequence variation, and mapping of the genes shows a bias of rearrangement based on chromosomal location. J. Immunol. 167:257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huetz, F., L. Carlsson, U.-C. Tornberg, and D. Holmberg. 1993. V-region directed selection in differentiating B lymphocytes. EMBO J. 12:1819–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall, A.J., G.E. Wu, and G.J. Paige. 1996. Frequency of VH81x usage during B cell development: initial decline in usage is independent of Ig heavy chain cell surface expression. J. Immunol. 156:2077–2084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viale, A.C., A. Coutinho, and A.A. Freitas. 1992. Differential expression of VH gene families in peripheral B cell repertoires of newborn or adult immunoglobulin H chain congenic mice. J. Exp. Med. 175:1449–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirkham, P.M., and H.W. Schroeder Jr. 1994. Antibody structure and the evolution of immunoglobulin V gene segments. Semin. Immunol. 6:347–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen, L., S. Chang, and C. Mohan. 2002. Molecular signatures of antinuclear antibodies-contributions of heavy chain CDR residues. Mol. Immunol. 39:333–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nitschke, L., J. Kestler, T. Tallone, S. Pelkonen, and J. Pelkonen. 2001. Deletion of the DQ52 element within the Ig heavy chain locus leads to a selective reduction in VDJ recombination and altered D gene usage. J. Immunol. 166:2540–2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koralov, S.B., T.I. Novobranseva, K. Hochedlinger, R. Jaenisch, and K. Rajewsky. 2005. Direct in vivo VH to JH rearrangement violating the 12/23 rule. J. Exp. Med. 201:341–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rolink, A.G., C. Schaniel, J. Andersson, and F. Melchers. 2001. Selection events operating at various stages in B cell development. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13:202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nemazee, D., and M. Weigert. 2000. Revising B cell receptors. J. Exp. Med. 191:1813–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forster, I., P. Vieira, and K. Rajewsky. 1989. Flow cytometric analysis of cell proliferation dynamics in the B cell compartment of the mouse. Int. Immunol. 1:321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine, M.H., A.M. Haberman, D.B. Sant'Angelo, L.G. Hannum, M.P. Cancro, C.A. Janeway Jr., and M.J. Shlomchik. 2000. A B-cell receptor-specific selection step governs immature to mature B cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:2743–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandik-Nayak, L., A. Bui, H. Noorchashm, A. Eaton, and J. Erikson. 1997. Regulation of anti-double-stranded DNA B cells in nonautoimmune mice: localization to the T-B interface of the splenic follicle. J. Exp. Med. 186:1257–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopes-Carvalho, T., and J.F. Kearney. 2004. Development and selection of marginal zone B cells. Immunol. Rev. 197:192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu, H., D. Tarlinton, W. Muller, K. Rajewsky, and I. Forster. 1991. Most peripheral B cells in mice are ligand selected. J. Exp. Med. 173:1357–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, Y., H. Li, and M. Weigert. 2002. Autoreactive B cells in the marginal zone that express dual receptors. J. Exp. Med. 195:181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shlomchik, M., M. Mascelli, H. Shan, M.Z. Radic, D. Pisetsky, A. Marshak-Rothstein, and M. Weigert. 1990. Anti-DNA antibodies from autoimmune mice arise by clonal expansion and somatic mutation. J. Exp. Med. 171:265–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wardemann, H., S. Yurasov, A. Schaefer, J.W. Young, E. Meffre, and M.C. Nussenzweig. 2003. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 301:1374–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zemlin, M., M. Klinger, J. Link, C. Zemlin, K. Bauer, J.A. Engler, H.W. Schroeder Jr., and P.M. Kirkham. 2003. Expressed murine and human CDR-H3 intervals of equal length exhibit distinct repertoires that differ in their amino acid composition and predicted range of structures. J. Mol. Biol. 334:733–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raaphorst, F.M., C.S. Raman, B.T. Nall, and J.M. Teale. 1997. Molecular mechanisms governing reading frame choice of immunoglobulin diversity genes. Immunol. Today. 18:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schroeder, H.W., Jr., G.C. Ippolito, and S. Shiokawa. 1998. Regulation of the antibody repertoire through control of HCDR3 diversity. Vaccine. 16:1383–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coutinho, A. 2001. Gigas and anthropiscus: evolution and development of Cohen's immunological homunculus. In Autoimmunity and Emerging Diseases. L. Steinman, editor. The Center for the Study of Emerging Diseases, Jerusalem. 54–63.

- 42.Boersch-Supan, M.E., S. Agarwal, M.E. White-Scharf, and T. Imanishi-Kari. 1985. Heavy chain variable region. Multiple gene segments encode anti-4-(hydroxy-3-nitro-phenyl)acetyl idiotypic antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 161:1272–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hagiwara, Y., J.R. McGhee, K. Fujihashi, R. Kobayashi, N. Yoshino, K. Kataoka, Y. Etani, M.N. Kweon, S. Tamura, T. Kurata, et al. 2003. Protective mucosal immunity in aging is associated with functional CD4+ T cells in nasopharyngeal-associated lymphoreticular tissue. J. Immunol. 170:1754–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torres, R., and R. Kuhn. 1997. Laboratory Protocols for Conditional Gene Targeting. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 184 pp.

- 45.Reth, M., G.J. Hammerling, and K. Rajewsky. 1978. Analysis of the repertoire of anti-NP antibodies in C57BL/6 mice by cell fusion. I. Characterization of antibody families in the primary and hyperimmune response. Eur. J. Immunol. 8:393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allman, D., R.C. Lindsley, W. DeMuth, K. Rudd, S.A. Shinton, and R.R. Hardy. 2001. Resolution of three nonproliferative immature splenic B cell subsets reveals multiple selection points during peripheral B cell maturation. J. Immunol. 167:6834–6840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oliver, A.M., F. Martin, G.L. Gartland, R.H. Carter, and J.F. Kearney. 1997. Marginal zone B cells exhibit unique activation, proliferative and immunoglobulin secretory responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:2366–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loder, F., B. Mutschler, R.J. Ray, C.J. Paige, P. Sideras, R. Torres, M.C. Lamers, and R. Carsetti. 1999. B cell development in the spleen takes place in discrete steps and is determined by the quality of B cell receptor-derived signals. J. Exp. Med. 190:75–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eisenberg, D. 1984. Three-dimensional structure of membrane and surface proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53:595–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.