Abstract

A pink-pigmented symbiotic bacterium was isolated from hybrid poplar tissues (Populus deltoides × nigra DN34). The bacterium was identified by 16S and 16S-23S intergenic spacer ribosomal DNA analysis as a Methylobacterium sp. (strain BJ001). The isolated bacterium was able to use methanol as the sole source of carbon and energy, which is a specific attribute of the genus Methylobacterium. The bacterium in pure culture was shown to degrade the toxic explosives 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazene (RDX), and octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5-tetrazocine (HMX). [U-ring-14C]TNT (25 mg liter−1) was fully transformed in less than 10 days. Metabolites included the reduction derivatives amino-dinitrotoluenes and diamino-nitrotoluenes. No significant release of 14CO2 was recorded from [14C]TNT. In addition, the isolated methylotroph was shown to transform [U-14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1) and [U-14C]HMX (2.5 mg liter−1) in less than 40 days. After 55 days of incubation, 58.0% of initial [14C]RDX and 61.4% of initial [14C]HMX were mineralized into 14CO2. The radioactivity remaining in solution accounted for 12.8 and 12.7% of initial [14C]RDX and [14C]HMX, respectively. Metabolites detected from RDX transformation included a mononitroso RDX derivative and a polar compound tentatively identified as methylenedinitramine. Since members of the genus Methylobacterium are distributed in a wide diversity of natural environments and are very often associated with plants, Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 may be involved in natural attenuation or in situ biodegradation (including phytoremediation) of explosive-contaminated sites.

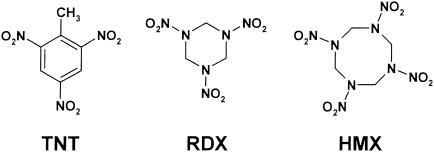

Best known for their explosive properties, 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine or royal demolition explosive (RDX), and octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine or high-melting-point explosive (HMX) are also environmental pollutants contaminating numerous military sites in Europe and North America (Fig. 1). First synthesized in 1863, TNT was used in the dye industry before becoming in the 20th century the main conventional explosive used by military forces worldwide. However, because of a higher stability and detonation power, nitramines HMX and RDX are at the present time the most-widespread conventional explosives. Manufacture of nitro-substituted explosives, testing and firing ranges, and destruction of ammunition stocks have generated toxic wastes, leading to large-scale contamination of soils and groundwater (46). Seven nitro-substituted explosives, including TNT and RDX, have been listed as priority pollutants by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (26). RDX, formerly used as a rat poison, is in addition considered a possible carcinogen by the EPA (4, 28). HMX has been listed by the EPA as a contaminant of concern (49). A lifetime health advisory of 2 μg of TNT liter−1 in drinking water and a water-quality limit of 105 μg of RDX liter−1 have been recommended (10, 38). Physicochemical properties, biodegradation, and toxicity of nitro-substituted explosives have been extensively reviewed in the literature (15, 19, 20, 39, 45, 47, 54).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of nitro-substituted explosives TNT, RDX, and HMX.

The toxicity of TNT has been reported since the First World War among English ammunition workers. From laboratory studies TNT, RDX, and HMX have been found to be toxic for most classes of organisms, including bacteria (48, 57), algae (48, 57), plants (36), earthworms (37), aquatic invertebrates (48, 49), and animals (24, 44), including mammals (28, 49) and humans (6, 24).

Traditional treatments of toxic ammunition wastes (e.g., open burning and open detonation, adsorption onto activated carbon, photooxidation, etc.) are costly, damaging for the environment, and in many cases practically infeasible. There is therefore a considerable interest in developing cost-effective biological alternatives based on microorganisms or plants. Biotransformation of energetic pollutants TNT, RDX, and HMX has been reported for different classes of organisms, including bacteria, fungi, and plants (7, 15, 20, 29, 33, 39, 42, 54, 59). Transformation of TNT typically involves a sequential reduction of the nitro groups to form toxic aromatic amino derivatives, which are somewhat further transformed (29, 33). Except with white-rot fungi, which secrete powerful ligninolytic peroxidases (11, 55), no significant mineralization has been detected in biological systems (29). In contrast to TNT, whose limiting degradation step is the aromatic ring fission, nitramines RDX and HMX undergo a change of molecular structure in which the ring collapses to generate small aliphatic metabolites (19, 54). While other decomposition mechanisms have been reported (i.e., concerted decomposition, bimolecular elimination, or hydrolysis [19]), biotransformation of RDX and HMX frequently involves an initial reduction of the nitro groups to form nitroso and hydroxylamino derivatives (31). The latter decompose to unstable aliphatic nitramines, which are eventually converted into N2O and CO2 (19, 20). Due to different conformations, HMX (crown type) is chemically more stable and therefore less amenable to biodegradation than RDX (chair type) (19).

Bacteria of the genus Methylobacterium are strictly aerobic, facultative methylotrophic, gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria that are able to grow on one-carbon compounds, e.g., methanol or methylamine (16, 33, 52). Members of the genus Methylobacterium, which belongs to the α-2 subclass of Proteobacteria, are distributed in a wide diversity of natural and human-made habitats, including soils, air, dust, freshwater, aquatic sediments, marine environments, water supplies, bathrooms, and masonry (21, 52). Some species have even been described as opportunistic human pathogens (52). In addition, methylotrophic bacteria frequently colonize the roots and the leaves of terrestrial and aquatic plant species (23, 35, 52). Bacteria are often red to pink due to the presence of carotenoids, and such bacteria are referred to as pink-pigmented facultative methylotrophs. Methylobacterium bacteria are highly resistant to dehydration, freezing, chlorination, UV light, ionizing radiation, and elevated temperatures (52).

Methylotrophic bacteria play ecologically important functions because they consume methane, whose greenhouse effect is 20 times higher than that of carbon dioxide (17, 52), and are known to degrade a wide range of organic pollutants, including methyl chloride (51), methyl bromide (14), methyl iodide (41), dichloromethane (13), methyl tert-butyl ether (32), methylated amines (53), ethylated sulfur-containing compounds (9), and cyanate and thiocyanate (58).

In the present study, a symbiotic pink-pigmented bacterium was isolated from poplar tissue cultures and plantlets (Populus deltoides × nigra DN34) and identified as a Methylobacterium sp. (referred to as strain BJ001). Because poplar cultures are used to study the phytotransformation of toxic nitro-substituted explosives (59), the bacterium was investigated for its capacity to transform in pure culture the energetic pollutants TNT, RDX, and HMX.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant tissue cultures and plant regeneration.

Imperial Carolina hybrid poplar cuttings (P. deltoides × nigra DN34) were obtained from Hramoor Nursery (Manistee, Mich.). Tissue cultures consisted of spherical green cell aggregates and were prepared from surface-sterilized explants as described elsewhere (56). Tissue cultures were routinely maintained in liquid Murashige and Skoog (MS) (32a) medium (supplemented with 30 g of sucrose liter−1, 5.0 mg of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid liter−1, and 1.0 mg of 6-furfurylaminopurine [kinetin] liter−1) with agitation (125 rpm) and under a photoperiod of 16 h of light and 8 h of dark. Tissue cultures were used directly for in vitro experiments as a laboratory model plant and for the regeneration of small plantlets.

Bacterial isolation, growth, and maintenance.

Red or pink single colonies were collected manually from different plant materials—i.e., from surface-sterilized explants, from tissue culture, or from regenerated plantlets—and isolated by streaking on Luria-Bertani (LB) solid medium (2.5% agar). Pure cultures of the isolated bacterium (strain BJ001 = ATCC BAA-705 = NCIMB 13946) were routinely maintained on the same LB solid medium at 28°C.

In order to maintain a selective pressure for methylotroph isolation, bacteria were alternatively cultivated in liquid minimal medium (see below) supplemented with methanol (0.5%, vol/vol) as a carbon source and ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) (1.2 g liter−1 [i.e., 3.0 mM N]) as a nitrogen source. Minimal medium, consisting of modified Jayasuriya's medium, contained the following in 1 liter of deionized water: K2HPO4, 1.74 g; NaH2PO4 · H2O, 1.38 g; Na2SO4, 0.54 g; MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.2 g; CaCl2 · 2H2O, 25 mg; FeCl2 · 4H2O, 3.5 mg; and mineral solution, 2 ml, at pH 7.0 (1).

Morphological, biochemical, and physiological analyses.

Gram staining was carried out according to standard protocols (12). Scanning electron microscopy observations were performed on dehydrated fixed material (glutaraldehyde-osmium tetroxide) coated with a gold-palladium mixture by using a Hitachi (Tokyo, Japan) S-4000 scanning electron microscope (5).

A dehydrated carbon source utilization test was based on a set of 49 organic compounds and was performed using the API 50CH system (Biomerieux, Montalieu-Vercieu, France). In addition, the isolated bacterium was cultivated in 50-ml conical flasks on minimal liquid medium supplemented with 1.2 g of NH4NO3 liter−1 (3.0 mM N) and various carbon sources added to a final concentration of 0.5% (vol/vol) (liquid substrates) or 5.0 g liter−1 (solid substrates), except for the following: formaldehyde (0.05%, vol/vol), TNT (1.0 g liter−1), RDX (1.0 g liter−1), and HMX (1.0 g liter−1). Carbon source utilization was determined after 2 weeks of incubation under agitation at room temperature. A biochemical test based on a set of 19 enzymatic assays was performed using the API ZYM system (Biomerieux).

Detection and identification of the isolated bacterium by rDNA analyses.

General techniques for DNA manipulations were carried out according to standard protocols (2, 40). Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted by centrifugation from 4-day pregrown cell suspensions using a DNeasy Tissue kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, Calif.). Extracted DNA was further purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation (2). For 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) PCR amplification, the following universal primers were synthesized: forward bacterial primer 27f (positions 11 to 27 of 16S rDNA, according to Escherichia coli numbering) and reverse bacterial primer 1513r (positions 1492 to 1513). For 16S-23S intergenic spacer (IGS) rDNA amplification, a forward primer, 926f (positions 901 to 926), and a reverse primer, 115r/23S (positions 97 to 115), were used (50). Total plant DNA was extracted from poplar explants and tissue cultures using a DNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). Three 16S rDNA fragments specific to Methylobacterium species were amplified using three pairs of primers: Mb2, including the primers 246f (positions 226 to 246 of bacterial 16S rDNA, E. coli numbering) and 459r (positions 439 to 459); Mb3, including the primers 876f (positions 856 to 876) and 1173r (positions 1153 to 1173); and Mb4, including the primers 668f (positions 650 to 668) and 1019r (positions 1001 to 1019) (33). PCR amplifications were carried out as described elsewhere (50). Purified PCR products were submitted for sequencing at the University of Iowa DNA Core Facility (Iowa City). The determined rDNA sequences, as well as reference sequences retrieved from NCBI GenBank (U.S. National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Md.), were aligned by ClustalW Multiple Alignment BioEdit (version 5.0.9) software (Raleigh, N.C.). The tree topology was inferred by the neighbor-joining method using Mega2 (version 2.1) software (27).

Degradation of TNT, RDX, and HMX.

Cell suspensions of Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 in pure culture were exposed separately to the nitro-substituted explosives TNT, RDX, and HMX. Bioreactors consisted of 250-ml conical flasks equipped with lateral tubing for sample collection and were closed by a rubber stopper. Flasks were equipped with a CO2 trap consisting of a 5-ml glass vial containing 1 ml of 1.0 N NaOH. Each bioreactor contained 100 ml of liquid LB medium supplemented with [U-ring-14C]TNT (25 mg liter−1), [U-14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1), or [U-14C]HMX (2.5 mg liter−1). Each flask was inoculated with a concentrated cell suspension (1.0%, vol/vol). The inoculum was prepared from log-phase cell suspensions and exhibited a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0 (i.e., approximately 1.0 × 109 cells ml−1). Bioreactors were incubated at room temperature under agitation (125 rpm). One-milliliter samples of the solution and the CO2 traps were collected periodically for analyses. Control experiments were carried out with noninoculated flasks or flasks inoculated with the bacteria but without toxic compound. Experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Additional degradation experiments using growing cells were carried out in minimal liquid medium supplemented with the following carbon and/or nitrogen sources: fructose (5.0 g liter−1) and NH4NO3 (1.2 g liter−1 [3 mM N]); fructose only; NH4NO3 only; and no fructose and no NH4NO3. Bioreactors were 30-ml serum vials equipped with a CO2 trap, which consisted of a 4-ml glass tube containing 500 μl of 1.0 N NaOH. Each bioreactor contained 10 ml of liquid medium supplemented separately with [U-ring-14C]TNT (25 mg liter−1), [U-14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1), or [U-14C]HMX (2.5 mg liter−1) and was inoculated with a concentrated cell suspension (1.0%, vol/vol). For each set of experiments, LB medium and noninoculated minimal medium were used as positive and negative control media, respectively.

Similar degradation experiments were carried out with other members of the genus Methylobacterium grown on LB medium supplemented with succinate (2.0 g liter−1): M. extorquens (ATCC 14718), M. organophilum (ATCC 27886), and M. rhodesianum (ATCC 21611).

Analyses.

Analyses of nitro-substituted compounds (i.e., TNT, RDX, HMX, and their metabolites) were performed by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (HP Series 1100; Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, Calif.) on a C18 Supelcosil LC-18 column (25 cm by 4.6 mm; packing material bead diameter, 5 μm; Supelco, Bellefonte, Pa.). The system was equipped with a UV-visible photodiode array detector (HP Series 1100), a mass spectrometry detector (1100 Series LC/MSD; Agilent, Palo Alto, Calif.), and a Radiomatic Flo-One β radio-chromatograph (Packard Bioscience, Meriden, Calif.) for the detection of 14C-labeled radioactive compounds. The mobile phase consisted of Ch3CN-0.1% (wt/vol) ammonium acetate (NH4CH3COO) running at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. For mass analyses, a Zorbax 80-Å Extended-C18 column (2.1 by 100 mm; diameter, 3.5 μm; Agilent) running at a flow rate of 0.2 ml min−1 was used. The mass spectrometer was equipped with an electrospray ionization source used in negative mode. Operating parameters were as follows: capillary voltage, 3.0 kV; drying gas flow, 12.0 liters min−1; nebulizer pressure, 35 lb/in2; drying gas temperature, 350°C. TNT and its metabolites were detected by their M-H ion masses, while RDX, HMX, and their metabolites were detected by their M + 60-H (acetate) ion masses.

14C radioactivity in solution, in extracts, and in CO2 traps was analyzed with a liquid scintillation counter (LS 6000IC; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, Calif.) using Ultima Gold XR (Packard Bioscience) as the scintillation cocktail.

Radioactivity remaining in the cells was analyzed using a biological oxidizer (OX600; R. J. Harvey Instrument, Hillsdale, N.J.). 14CO2 contained in outgoing gases was trapped into 10 ml of carbon-14 cocktail (R. J. Harvey Instrument), and the radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Bacterial growth was recorded by the OD600 and by biomass (dry weight). Cell concentrations were determined by direct counting.

Chemicals.

[U-14C]RDX and [U-14C]HMX were purchased from DuPont NEN (Boston, Mass.) and exhibited an initial specific activity of 307 and 252 MBq mmol−1, respectively. Both [14C]RDX and [14C]HMX were mixed with corresponding nonlabeled compounds to obtain final specific activities of 167 to 337 and 59 to 111 Bq mmol−1 for [14C]RDX and [14C]HMX, respectively. [U-ring-14C]TNT was purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life Science (Boston, Mass.) and exhibited an initial activity of 1.5 GBq mmol−1. [14C]TNT was mixed with nonlabeled TNT to give a final specific activity of 78 to 122 Bq mmol−1.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S and 16S-23S IGS rDNA sequence from Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 (= ATCC BAA-705 = NCIMB 13946) has been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number AY182525. The accession numbers for the sequences used in the phylogenic analyses are as follows: M. extorquens, D32224; Methylobacterium mesophilicum, AJ400919; Methylobacterium nodulans, AF220763; M. organophilum, D32226; Methylobacterium radiotolerans, D32227; Methylobacterium rhodesianum, D32228; Methylobacterium rhodinum, D32229; and Methylobacterium zatmanii, L20804.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of a pink-pigmented facultative methylotroph bacterium.

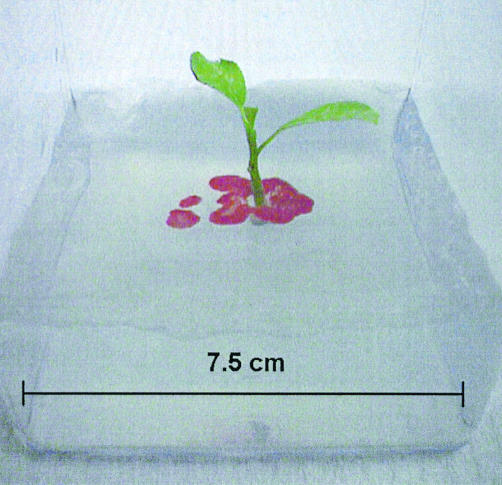

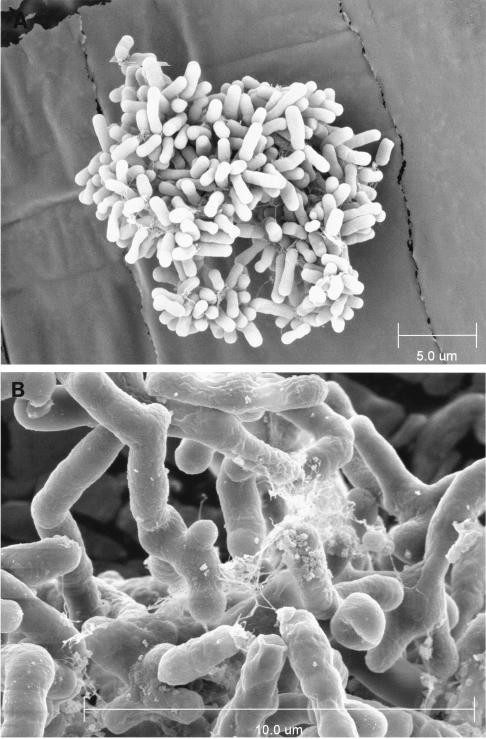

A pink-pigmented bacterium was isolated from poplar tissue cultures and plantlets (P. deltoides × nigra DN34) cultivated under axenic conditions. Tissue cultures in liquid medium and intact plantlets (regenerated from in vitro tissues) did not show microbial contamination. However, plant tissues on plates of modified MS semisolid medium frequently turned red, while excised plantlets showed the development of bright-red colonies spreading from the plant material (Fig. 2), suggesting the presence of a bacterium associated with or within poplar tissues. The isolated bacterium—referred to as strain BJ001 and deposited under the accession numbers ATCC BAA-705 and NCIMB 13946—was propagated routinely on LB solid medium at 28°C. Standard staining procedures and microscopic observations revealed a gram-negative, nonsporulating, rod-shaped bacterium (Fig. 3A) developing a filamentous and branched phenotype in liquid suspension (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 2.

Poplar plantlet (P. deltoides × nigra DN34) regenerated from in vitro tissue cultures and cultivated on semisolid modified MS medium. Red colonies of Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 are well visible.

FIG. 3.

Scanning electron microscopy pictures of Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 cultivated on solid LB medium (A) and in liquid LB medium (B).

The isolated strain was identified as a Methylobacterium sp. by using 16S rDNA analysis. Phylogenetic relationships were confirmed by 16S-23S IGS rDNA analysis. According to the 16S rDNA sequence similarity matrix, the closest relatives to Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 are Methylobacterium thiocyanatum, M. extorquens, M. zatmanii, and M. rhodesianum, with sequence similarities of 99.3, 99.1, 98.6, and 98.5%, respectively. In order to show the close association between plant tissues and strain BJ001, 16S rDNA fragments specific to Methylobacterium species were amplified from plant and bacterial DNA extracts (34). Three targeted fragments were PCR amplified using specific primer pairs Mb2, Mb3, and Mb4 from both DNA extracts of pure cultures of Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 and from leaves of P. deltoides × nigra DN34, but not from the control DNA, i.e., DNA extracted from tobacco leaves (Nicotiana tabacum) and from pure cultures of Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Only 16S rDNA universal primers gave a PCR product using the control DNA.

The bacterium was shown to grow on different C1 carbon sources, including methanol, methylamine, and formaldehyde, which is a particular attribute of the genus Methylobacterium. Other carbon substrates sustaining growth of Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 included fructose, glycerol, ethanol, and a wide range of organic acids. A doubling time of 9.7 h has been determined for Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 growing on LB medium supplemented with fructose (0.5%, wt/vol), the best carbon source for supporting the growth of BJ001. On the other hand, no growth was observed on glucose, saccharose, arabinose, galactose, iso-propanol, n-butanol, chloromethane, dichloromethane, TNT, RDX, or HMX. Using biochemical assays, strain BJ001 tested positive for the following enzymatic reactions: alkaline phosphatase (2-naphthyl phosphate), esterase C4 (2-naphthyl butyrate), esterase C8 (2-naphthyl caprylate), valine arylamidase (l-valyl-2-naphthylamide), α-chymotrypsin (N-glutaryl-phenylalanine-2-naphthylamide), acid phosphatase (2-naphtyl phosphate), and naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase (6-bromo-2-phosphohydroxy-3-naphthoic acid o-anisidide).

Degradation of TNT, RDX, and HMX.

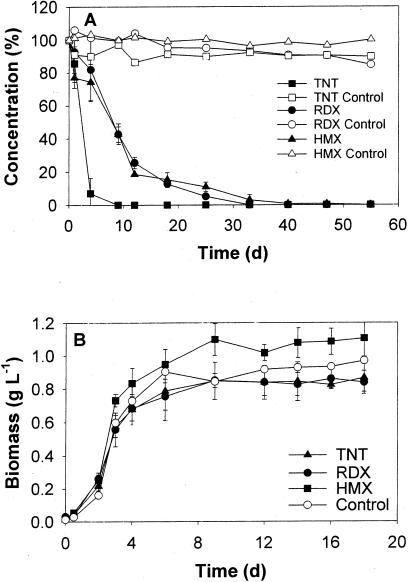

Pure cultures of Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 grown in liquid LB medium were exposed separately to [14C]TNT (25 mg liter−1), [14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1), and [14C]HMX (2.5 mg liter−1). Bacteria were shown to fully transform the nitro-substituted explosives over the 55 days of experiment (Fig. 4A). Bacterial biomasses (monitored by the OD600) grown on fructose showed typical growth curves and were not significantly affected by the presence of TNT, RDX, or HMX (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Transformation of TNT (25 mg liter−1), RDX (20 mg liter−1), and HMX (2.5 mg liter−1) by pure cultures of Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001. (A) TNT, RDX, and HMX concentrations remaining in solution are shown and were determined by HPLC (UV absorbance at 230 nm). Control experiments consisted of noninoculated bioreactors. Concentrations are expressed in percentage of the initial level. (B) Biomass growths on fructose in the presence of TNT, RDX, and HMX are presented. Bacterial biomasses were determined by the OD600. Control experiments were conducted without nitro-substituted explosives. Error bars, standard deviations.

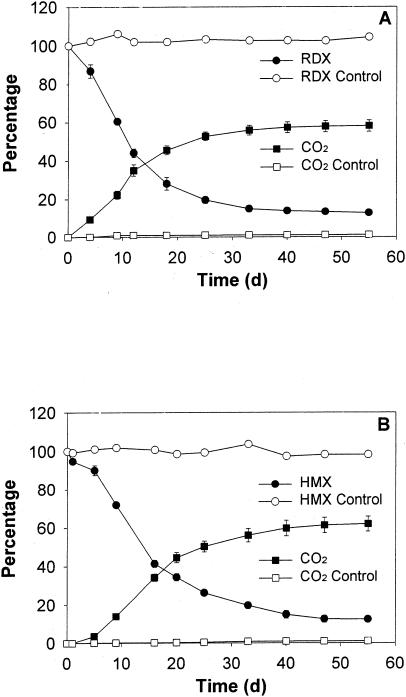

While TNT disappeared completely in less than 10 days, no significant mineralization (i.e., release of 14CO2) or decrease of the radioactivity in solution was observed (Table 1). In contrast, RDX and HMX concentrations decreased more slowly (reaching nondetectable levels after 40 days), but with a significant release of 14CO2, corresponding to 58.0% ± 3.0% and 62.0% ± 3.9% of the initial radioactivity, respectively (Fig. 5; Table 1). As a consequence, the radioactivity remaining in solution decreased to 12.8% ± 1.5% and 12.5% ± 1.3% of the initial dose after 55 days. Radio-chromatograms of the CO2 traps showed only a single peak, identified as aqueous 14CO2 by comparison with an NaH14CO3 standard. No significant mineralization or change in the initial concentration or radioactivity was observed in control experiments.

TABLE 1.

Mass balance for [14C]TNT, [14C]RDX, and [14C]HMXa

| Solution (%) | % Radioactivity recovered after treatment with:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14C]TNT (25 mg liter−1)

|

[14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1)

|

[14C]HMX (2.5 mg liter−1)

|

||||

| Cells | Control | Cells | Control | Cells | Control | |

| Final | 93.3 ± 3.4 | 103.4 | 12.8 ± 1.5 | 104.4 | 12.5 ± 1.3 | 98.3 |

| Bacterial cell | 6.3 ± 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Mineralization | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.6 | 58.0 ± 3.0 | 1.2 | 62.0 ± 3.9 | 1.1 |

| Mass balance | 100.3 ± 4.7 | 104.2 | 71.8 ± 4.7 | 105.6 | 75.4 ± 5.4 | 99.6 |

[14C]TNT, [14C]RDX, and [14C]HMX were treated with Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 growing in LB liquid medium after 55 days of exposure. Radioactivity is expressed as a percentage of the initial dose. Control experiments were carried out with noninoculated flasks. Results are presented as means ± standard deviations.

FIG. 5.

Mineralization of [14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1) (A) and [14C]HMX (2.5 mg liter−1) (B) by pure cultures of Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001. Radioactivity remaining in solution and release of 14CO2 are presented. Experiments were conducted with bacterial cell suspensions and in controls consisting of noninoculated bioreactors. Radioactivity in solution and release of 14CO2 are expressed as a percentage of the initial level. Error bars, standard deviations.

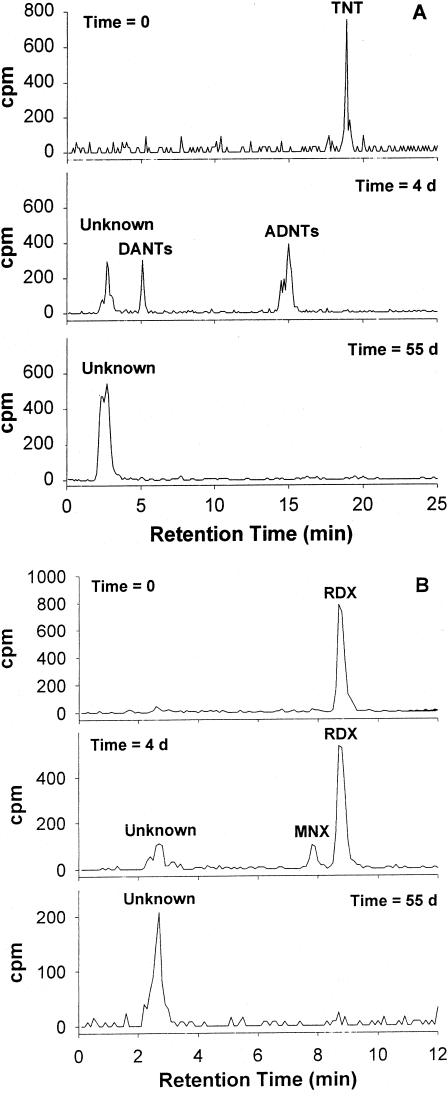

A radio-chromatogram of the solution containing TNT at the beginning of the experiment showed a single peak, which eluted after 18.9 min and corresponded to [14C]TNT (Fig. 6A). After 4 days, the radioactivity was distributed in three peaks that eluted after 15.0, 5.1, and 2.7 min, respectively. At the end of the treatment, the radioactivity was concentrated in a single peak, which eluted after 2.7 min. Spectral analysis of the second and third peaks (which eluted after 15.0 and 5.1 min) gave masses of 196 [M-H]− and 166 [M-H]− kDa, respectively, suggesting the presence of amino-dinitrotoluenes (ADNTs) (molecular mass = 197 kDa) and diamino-nitrotoluenes (DANTs) (molecular mass = 167 kDa). The profile of metabolite formation showed the transient appearance of ADNTs and DANTs, which reached a maximum after 4 and 18 days, respectively, and the final accumulation of unknown compound(s), accounting for 94.3% of the initial radioactivity.

FIG. 6.

Experimental degradation of [14C]TNT (25 mg liter−1) (A) and [14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1) (B) by pure cultures of Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001. Radio-chromatograms obtained from HPLC analysis (C18 column) of the liquid medium at time zero, after 4 days, and after 55 days of incubation are presented.

Radio-chromatograms of the solution containing RDX at the beginning of the experiment showed a single peak, which eluted after 8.7 min (Fig. 6B). After 4 days, the remaining radioactivity was concentrated in three peaks, which eluted after 8.7, 7.8, and 2.7 min, respectively. Radioactivity after 55 days was concentrated in a single peak, which eluted after 2.7 min. The first peak (which eluted after 8.7 min) was characterized by a mass of 281 kDa [M + 60-H]− and corresponded to initial RDX. The second peak (7.8 min) was characterized by a mass of 265 kDa [M + 60-H]− and was identified as the mononitroso derivative of RDX (MNX). The final metabolite(s) eluted after 2.7 min exhibited an ion mass of 135 kDa [M-H]−, suggesting the generation of methylenedinitramine (O2NNHCH2NHNO2). The concentration of MNX reached a maximum after 4 days before decreasing slowly to an undetectable level. An unidentified metabolite(s) accumulated in the solution and accounted for 14.9% of the initial radioactivity after 55 days. In addition to mass spectral analyses, the identification of ADNTs, DANTs, and MNX was confirmed by comparison of their retention times and UV spectra with authentic standards.

To determine whether the transformation and mineralization of nitro-substituted explosives was metabolic or cometabolic (i.e., associated or not with carbon and/or nitrogen utilization), Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 was grown on minimal medium supplemented separately with [14C]TNT (25 mg liter−1), [14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1), or [14C]HMX (2.5 mg liter−1) in the presence and in the absence of carbon and/or nitrogen sources (Table 2). In all sets of experiments (with and without [14C]TNT, [14C]RDX, or [14C]HMX), only minimal medium supplemented with fructose (5.0 g liter−1) supported bacterial growth (reaching 0.7 to 1.1 g of biomass [dry weight] liter−1 after the 20 days), regardless of the presence of a nitrogen source. Significant mineralization of nitramines (accounting for 7.0 to 7.7% of the initial [14C]RDX and 5.0 to 6.8% of the initial [14C]HMX) was observed under the same conditions, i.e., in the presence of fructose. No significant mineralization of [14C]TNT was recorded. Mineralization rates of nitramines [14C]RDX and [14C]HMX were shown to be higher when the bacterium was grown on LB medium (i.e., 18.1 and 15.5% of the initial radioactivity, respectively). Interestingly, nitrogen-free control medium (i.e., without TNT, RDX, or HMX) was able to sustain bacterial growth (reaching 1.1 g of biomass [dry weight] liter−1), as long as a carbon source (e.g., fructose) was provided. For all sets of experiments, neither significant biomass growth nor release of 14CO2 was recorded in the absence of a carbon source or from noninoculated control flasks.

TABLE 2.

Mineralization of [14C]RDX, [14C]HMX, and [14C]TNT by Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 after 20 days of exposurea

| Substrate | [14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1)

|

[14C]HMX (2.5 mg liter−1)

|

[14C]TNT (25 mg liter−1)

|

Controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14CO2 (%) | Biomass (mg liter−1) | 14CO2 (%) | Biomass (mg liter−1) | 14CO2 (%) | Biomass (mg liter−1) | ||

| Minimal medium with: | |||||||

| Fructose and NH4NO3 | 7.74 ± 0.33 | 1.03 ± 0.11 | 6.75 ± 0.66 | 1.02 ± 0.22 | 0.34 ± 0.13 | 0.97 ± 0.06 | 1.06 ± 0.08 |

| Fructose | 7.03 ± 0.91 | 0.74 ± 0.16 | 5.03 ± 0.32 | 1.07 ± 0.05 | 0.25 ± 0.17 | 0.97 ± 0.13 | 1.08 ± 0.14 |

| NH4NO3 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.08 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.10 | 0.16 ± 0.08 | 0.11 ± 0.03 |

| No fructose and no NH4NO3 | 0.19 ± 0.15 | 0.14 ± 0.08 | 0.18 ± 0.14 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 0.19 ± 0.13 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.17 ± 0.05 |

| Positive control | 18.08 ± 3.03 | 1.05 ± 0.07 | 15.54 ± 1.8 | 1.08 ± 0.06 | 0.56 ± 0.07 | 1.06 ± 0.15 | 1.12 ± 0.07 |

| Negative control | 0.35 ± 0.23 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.22 ± 0.24 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

Cells were grown on minimal medium supplemented with the following carbon and/or nitrogen sources: fructose (5.0 g liter−1) and NH4NO3 (1.2 g liter−1 [3.0 mM]), fructose only, NH4NO3 only, and no fructose and no NH4NO3. For each set of experiment, LB medium and noninoculated minimal medium were used as positive and negative control media, respectively. Control experiments consisted of the same set of media without addition of [14C]RDX, [14C]HMX, or [14C]TNT. Results are presented as means ± standard deviations.

The ability to mineralize nitramines RDX and HMX was investigated among other representative members of the genus Methylobacterium. Although strain BJ001 exhibited higher mineralization rates, the other Methylobacterium strains tested were also able to significantly mineralize nitramine explosives (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Mineralization of [14C]RDX, [14C]HMX, and [14C]TNT by members of the genus Methylobacterium after 20 days of exposurea

| Strain |

14CO2 (%)

|

Biomass (mg liter−1)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1) | [14C]HMX (2.5 mg liter−1) | [14C]TNT (25 mg liter−1) | [14C]RDX (20 mg liter−1) | [14C]HMX (2.5 mg liter−1) | [14C]TNT (25 mg liter−1) | |

| M. extorquens | 15.2 ± 2.4 | 13.8 ± 1.9 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 1.01 ± 0.10 | 1.12 ± 0.06 | 1.07 ± 0.08 |

| M. organophilum | 8.4 ± 3.0 | 8.1 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 1.23 ± 0.07 | 1.19 ± 0.10 | 1.13 ± 0.05 |

| M. rhodesianum | 13.7 ± 3.2 | 11.6 ± 2.0 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.95 ± 0.15 | 0.98 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.04 |

| BJ001 | 18.5 ± 1.7 | 17.2 ± 2.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.98 ± 0.11 | 0.99 ± 0.06 | 0.97 ± 0.05 |

| Control | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.07 |

Cells were grown on LB medium supplemented with succinate (2.0 g liter−1). Control experiments were carried out with noninoculated flasks. Results are presented as means ± standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 was isolated from poplar tissues (P. deltoides × nigra DN34) and belongs to the α-2 subclass of Proteobacteria. It is has been shown to be related to M. extorquens, a widely distributed methylotrophic bacterium frequently associated with plant leaves and roots (52). Even though association with a poplar tree (Populus sp.) has not been previously described, members of the genus Methylobacterium are known to be common inhabitants of the rhizosphere and the phyllosphere of plants and have even been described as chronic contaminants of plant tissue cultures (22, 23, 30, 52).

In vitro poplar tissue cultures and plantlets have been used routinely in our laboratory for phytoremediation studies (59) and were maintained for months without showing microbial contamination. A transient red coloration of plant tissues, as well as red colonies spreading from plant materials, suggests that Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 is an endophyte. Surface sterilization of original explants and manipulations under sterile conditions should ensure microbe-free plant tissues, except in the case of endophytic bacteria. Indeed, in addition to colonizing the rhizosphere and the phyllosphere, Methylobacterium bacteria are known to colonize internal plant tissues (i.e., endophytic bacteria) (23, 35). Finally, the ability of Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 to metabolize fructose faster than any other carbon sources (fructose is the first hexose produced by photosynthesis) also suggests an endophytic ecology. Amplification of 16S rDNA fragments using primer pairs specific to Methylobacterium bacteria (34) from total DNA extracts of poplar leaves suggests a close symbiotic association but does not provide final evidence for an endophytic bacterium, because microbes may be attached to plant surfaces and resist sterilization.

Besides being the first report of a symbiotic methylotroph associated with a Populus sp., this work provides the first evidence that Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 is able to transform TNT and to mineralize RDX and HMX into CO2. The transient generation of reduction derivatives early in the degradation process (i.e., ADNTs and DANTs from TNT and MNX from RDX) indicates that the transformation of explosives by Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 begins via a reduction reaction. Bacterial transformation of heterocyclic nitramines frequently involves an initial reduction step (31), and nitroso metabolites have been previously detected, under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions (18, 20). On the other hand, being a highly oxidized molecule, TNT is easily reduced, and the stepwise reduction of the nitro groups, with the subsequent generation of reduction derivatives (i.e., hydroxylaminodinitrotoluenes, ADNTs, and DANTs), is known to be the major transformation pathway of TNT (57).

However, following these early reduction steps, the fates of the nitroaromatic explosive TNT and of heterocyclic nitramines RDX and HMX diverge considerably. Although the transformation of [14C]RDX and [14C]HMX by Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 resulted in an extensive release of 14CO2, no significant mineralization of [14C]TNT was observed. Mineralization of RDX and HMX by bacteria is well documented (4, 7, 19, 20, 25, 54). A slight change in the chemical structure of heterocyclic nitramines destabilizes the entire molecule (inner C-N bonds are less than 2 kcal mol−1), resulting in a ring cleavage generating various aliphatic hydroxylamines and nitramines (19, 20, 54). The latter may decompose and/or rearrange, eventually producing methanol (CH3OH), formaldehyde (CH2O), CO2, and N2O (20, 33). Nitramine-degrading bacteria often use RDX as the sole nitrogen source (4, 7, 20, 25). Even though mineralization and formation of 14CO2 were observed, our results suggest that Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001 is unable to use heterocyclic nitramines as carbon and/or nitrogen sources and that the capacity to degrade explosives is purely cometabolic. Although evidence has recently been provided about the implication of cytochrome P450 in the degradation of RDX by Rhodococcus strains (3, 8, 43), the detection of a mononitroso derivative makes this mechanism unlikely in Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001. On the other hand, the comparatively high mineralization rates of RDX and HMX into CO2 reported here may be related to the particular ability of Methylobacterium bacteria to metabolize C1 carbon substrates (e.g., CH2O or CH3OH), which are frequently generated from nitramine degradation. Note that BJ001 was originally isolated from poplar tissues not previously exposed to TNT, RDX, or HMX. Therefore, neither the plant-bacterium symbiotic association nor the capacity of BJ001 to transform explosives can be seen as the result of a selective pressure originating from exposure to energetic pollutants.

In contrast to RDX and HMX, which are easily fragmented, nitroaromatic TNT is usually not mineralized. Indeed, even though TNT was very quickly transformed (i.e., reduced) by Methylobacterium sp. strain BJ001, no significant release of CO2 was recorded. For several decades, bacterial degradation of nitroaromatic compounds has been known to lead to the formation of “dead-end” reduced derivatives not further transformed (29, 33). Although bacterial transformation of TNT did not lead to a complete detoxification (i.e., mineralization), recalcitrant reduction metabolites are significantly less toxic than parent TNT (26) and may be bound to soil particles and humic acids or be conjugated to organic molecules, resulting in a reduction of bioavailability and toxicity (6).

The capacity to metabolize explosives is a common feature among bacteria (29, 33). However, this is the first time that a member of the genus Methylobacterium has been shown to transform (and to mineralize into CO2) TNT, RDX, and HMX. The significant rates of mineralization of RDX and HMX achieved by other Methylobacterium strains—i.e., M. extorquens, M. organophilum, and M. rhodesianum—suggest that the ability demonstrated by strain BJ001 is shared by the other members of the genus. Since Methylobacterium bacteria are widespread in a variety of environments, including soils, sediments, freshwater, and plants, their involvement in natural attenuation or phytoremediation of toxic explosives may be of ecological importance.

Acknowledgments

We thank SERDP, Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (award number 02 CU13-17), for financial support. This is a contribution of the W. M. Keck Phytotechnologies Laboratory at the University of Iowa, supported by a gift from the W. M. Keck Foundation.

We benefited from discussion and help in the laboratory from Craig L. Just, Jeremy Rentz, and Joshua Shrout.

REFERENCES

- 1.Attwood, M. M., and W. Harder. 1972. A rapid and specific enrichment procedure for Hyphomicrobium spp. Antonie Leeuwenhook 38:369-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1999. Short protocols in molecular biology, 4th ed. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Bhushan, B., S. Trott, J. C. Spain, A. Halasz, L. Pacquet, and J. Hawari. 2003. Biotransformation of hexahydro-1, 3, 5-trinitro-1, 3, 5-triazine (RDX) by a rabbit liver cytochrome P450: insight into the mechanism of RDX biodegradation by Rhodococcus sp. strain DN22. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1347-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binks, P. R., S. Nicklin, and N. C. Bruce. 1995. Degradation of hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (Rdx) by Stenotrophomonas-Maltophilia Pb1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1318-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyde, A. 1978. Pros and cons of critical point drying and freeze-drying for SEM. Scan. Electr. Microsc. II 30:3-14. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruns-Nagel, D., T. C. Schmidt, O. Drzyzga, E. von Löw, and K. Steinbach. 1999. Identification of oxidized TNT metabolites in soil samples of a former ammunition plant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 6:7-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman, N. V., D. R. Nelson, and T. Duxbury. 1998. Aerobic degradation of hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) as a nitrogen source by Rhodococcus sp. strain DN22. Soil Biol. Biochem. 30:1159-1167. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman, N. V., J. C. Spain, and T. Duxbury. 2002. Evidence that RDX biodegradation by Rhodococcus strain DN22 is plasmid-borne and involves a cytochrome P-450. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93:463-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeZwart, J. M., P. N. Nelisse, and J. G. Kuenen. 1996. Isolation and characterization of Methylophaga sulfidovorans sp. nov.: an obligate methylotrophic aerobic, dimethyl sulfide-oxidizing bacterium from a microbial mat. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 20:261-270. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etnier, E. L. 1989. Water quality criteria for hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX). Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacolol. 9:147-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernando, T., J. A. Bumpus, and S. D. Aust. 1990. Biodegradation of TNT (2,4,6-trinitrotoluene) by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1666-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerhardt, P., R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg. 1994. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 13.Gisi, D., L. Willi, H. Tarber, T. Leisinger, and S. Vuilleumier. 1998. Effects of bacterial host and dichloromethane dehalogenase on the competitiveness of methylotrophic bacteria growing with dichloromethane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1194-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodwin, K. D., R. K. Varner, P. M. Crill, and R. S. Oremland. 1995. Consumption of tropospheric levels of methyl bromide by C1 compound-utilizing bacteria and comparison to saturation kinetics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5437-5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorontzy, T., O. Drzyzga, M. W. Kahl, D. Bruns-Nagel, J. Breitung, E. von Loew, and K. H. Blotevogel. 1994. Microbial degradation of explosives and related compounds. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 20:265-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green, P. N. 1992. The genus Methylobacterium, p. 2342-2349. In A. Balows, H. G. Truper, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, and K. H. Schleifer (ed.), The prokaryotes, 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 17.Hanson, R. S., and T. E. Hanson. 1996. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 60:439-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harkins, V. R., T. Mollhagen, C. Hientz, and K. Rainwater. 1999. Aerobic degradation of high explosives, phase I—HMX. Biorem. J. 3:285-290. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawari, J. 2000. Biodegradation of RDX and HMX: From basic research to field application, p. 277-310. In J. C. Spain, J. B. Hughes, and H. J. Knackmuss (ed.), Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds and explosives. Lewis Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 20.Hawari, J., S. Baudet, A. Halasz, S. Thiboutot, and G. Ampleman. 2000. Microbial degradation of explosives: biotransformation versus mineralization. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 54:605-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiraishi, A., K. Furuhata, A. Matsumoto, K. A. Koike, M. Fukuyama, and K. Tabuchi. 1995. Phenotypic and genetic diversity of chlorine-resistant Methylobacterium strains isolated from various environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2099-2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holland, M. A. 1997. Occam's razor applied to hormonology: are cytokinins produced by plants? Plant. Physiol. 115:865-868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland, M. A., and J. C. Polacco. 1994. PPFMs and other covert contaminants: is there more to plant physiology than just plants? Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 45:197-209. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honeycutt, M. E., A. S. Jarvis, and V. A. McFarland. 1996. Cytotoxicity and mutagenicity of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene and its metabolites. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 35:282-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones, A. M., C. W. Greer, G. Ampleman, S. Thiboutot, J. Lavigne, and J. Hawari. 1995. Biodegradability of selected highly energetic pollutants under aerobic conditions, p. 251-257. In R. Hinchee, R. E. Hoeppel, and D. B. Anderson (ed.), 3rd International In Situ and On Site Bioreclamation Symposium. Battle Press, Columbus, Ohio.

- 26.Keith, L. H., and W. A. Telliard. 1979. Priority pollutants: a perspective view. Environ. Sci. Technol. 13:416-423. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jokobsen, and M. Nei. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17:1244-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lachance, B., P. Y. Robidoux, J. Hawari, G. Ampleman, S. Thiboutot, and G. I. Sunahara. 1999. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of energetic compounds on bacterial and mammalian cells in vitro. Mutat. Res. 444:25-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenke, H., C. Achtnich, and H. J. Knackmuss. 2000. Perspectives of bioelimination of polyaromatic compounds, p. 91-126. In J. C. Spain, J. B. Hughes, and H. J. Knackmuss (ed.), Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds and explosives. Lewis Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 30.Lidstrom, M. E., and L. Chistoserdova. 2002. Plants in the pink: cytokinin production by Methylobacterium. J. Bacteriol. 184:1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCormick, N. G., J. H. Cornel, and A. M. Kaplan. 1981. Biodegradation of hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 42:817-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mo, K., C. O. Lora, A. E. Wanken, M. Javanmardian, X. Yang, and C. F. Kupla. 1997. Biodegradation of methyl t-butyl ether by pure bacteria cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47:69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Murashige, T., and F. Skoog. 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15:473-497. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishino, S. F., J. C. Spain, and Z. He. 2000. Strategies for aerobic degradation of nitroaromatic compounds by bacteria: process discovery or field application, p. 7-61. In J. C. Spain, J. B. Hughes, and H. J. Knackmuss (ed.), Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds and explosives. Lewis Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 34.Nishio, T., T. Yoshikura, and H. Itoh. 1997. Detection of Methylobacterium species by 16S rRNA gene-targeted PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1594-1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pirtilla, A. M., H. Laukkanen, H. Pospiech, R. Myllyla, and A. Hohtola. 2000. Detection of intracellular bacteria in the buds of Scotch pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) by in situ hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3073-3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robidoux, P. Y., G. Bardai, L. Paquet, G. Ampleman, S. Thiboutot, J. Hawari, and G. I. Sunahara. 2003. Phytotoxicity of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) and octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine (HMX) in spiked artificial and natural forest soils. Arch. Environ. Contam. Tox. 44:198-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robidoux, P. Y., C. Svendsen, J. Caumartin, J. Hawari, G. Ampleman, S. Thiboutot, J. M. Weeks, and G. I. Sunahara. 2000. Chronic toxicity of energetic compounds in soil determined using the earthworm (Eisenia andrei) reproduction test. Environ. Tox. Chem. 19:1764-1773. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross, R. H., and W. R. Hartley. 1990. Comparison of water quality criteria and health advisories for 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT). Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 11:114-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosser, S. J., A. Basran, E. R. Travis, C. E. French, and N. C. Bruce. 2001. Microbial transformation of explosives. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 49:1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russel. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, N.Y.

- 41.Schaefer, J. K., and R. S. Oremland. 1999. Oxidation of methyl halides by the facultative methylotroph strain IMB-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5035-5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnoor, J. L., L. A. Licht, S. C. McCutcheon, N. L. Wolfe, and L. H. Carriera. 1995. Phytoremediation of organic and nutrient contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 29:318A-323A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seth-Smith, H. M. B., S. J. Rosser, A. Basran, E. R. Travis, E. R. Dabbs, S. Nicklin, and N. C. Bruce. 2002. Cloning, sequencing, and characterization of the hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine degradation gene cluster from Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4764-4771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smock, L. A., D. L. Stoneburner, and J. R. Clark. 1976. The toxic effects of trinitrotoluene (TNT) and its primary degradation products on two species of algae and the fathead minnow. Water. Res. 10:537-543. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spain, J. C. 1995. Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Spain, J. C. 2000. Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds and explosives: introduction, p. 1-6. In J. C. Spain, J. B. Hughes, and H. J. Knackmuss (ed.), Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds and explosives. Lewis Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 47.Spain, J. B., J. B. Hughes, and H. J. Knackmuss. 2000. Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds and explosives. Lewis Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 48.Sunahara, G. I., S. Dodard, M. Sarrazin, L. Paquet, J. Hawari, C. W. Greer. G. Ampleman, S. Thiboutot, and A. Y. Renoux. 1999. Ecological characterization of energetic substances using a soil extraction procedure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 43:138-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Talmage, S. S., D. M. Opresko, C. J. Maxwell, C. J. Welsh, F. M. Cretella, P. H. Reno, and F. B. Daniel. 1999. Nitroaromatic munitions compounds: environmental effects and screening values. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 161:1-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan, Z., T. Hurek, P. Vinuesa, P. Muller, and J. K. Ladha. 2001. Specific detection of Bradyrhizobium and Rhizobium strains colonizing rice (Oryza sativa) roots by 16S-23S ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer-targeted PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3655-3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tourova, T. P., B. B. Kuznetsov, N. V. Doronina, and Y. A. Trotsenko. 2001. Phylogenic analysis of dichloromethane-utilizing aerobic methylotrophic bacteria. Microbiology 70:92-97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trotsenko, Y. A., E. G. Ivanova, and N. V. Doronina. 2001. Aerobic methylotrophic bacteria as phytosymbionts. Microbiology 70:725-736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trotsenko, Y. A., and N. V. Loginova. 1979. Pathways involved in the metabolism of methylated amines in bacteria. Usp. Mikrobiol. 14:28-55. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Aken, B., and S. N. Agathos. 2001. Biodegradation of nitrosubstituted explosives by white-rot fungi: a mechanistical approach. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 48:1-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Aken, B., M. Hofrichter, K. Scheibner, A. I. Hatakka, H. Naveau, and S. N. Agathos. 1999. Transformation and mineralization of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) by manganese peroxidase from the white-rot basidiomycete Phlebia radiata. Biodegradation 10:83-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Aken, B., and J. L. Schnoor. 2002. Evidence of perchlorate (ClO4−) reduction in plant tissues (poplar tree) using radio-labeled 35ClO4−. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:2783-2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Won, W. D., L. H. DiSalvo, and J. Ng. 1976. Toxicity and mutagenicity of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene and its microbial metabolites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 31:576-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wood, A. P., P. K. Donovan, I. R. McDonald, S. L. Jordan, T. D. Morgan, S. Khan, J. C. Murrel, and E. Borodina. 1998. A novel pink-pigmented facultative methylotroph, Methylobacterium thiocyanatum sp. nov., capable of growth on thiocyanate or cyanate as sole nitrogen source. Arch. Microbiol. 169:148-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoon, J. M., B. T. Oh, C. L. Just, and J. L. Schnoor. 2002. Uptake and leaching of octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine by hybrid poplar trees. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:4649-4655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]