Abstract

Premature activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis manifests as gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty. The mechanisms behind HPG activation are complex and a clear etiology for early activation is often not elucidated. Though collectively uncommon, the neoplastic and developmental causes of gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty are very important to consider, as a delay in diagnosis may lead to adverse patient outcomes. The intent of the current paper is to review the neoplastic and developmental causes of gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty. We discuss the common CNS lesions and human chorionic gonadotropin-secreting tumors that cause sexual precocity, review the relationship between therapeutic radiation and gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty, and finally, provide an overview of the therapies available for height preservation in this unique patient population.

1. Introduction

The onset of isosexual puberty is typically heralded by breast development in girls and testicular enlargement in boys, usually followed by pubarche/adrenarche, the pubertal growth spurt, and completion of secondary sexual development. Traditionally, normal pubertal onset is considered to occur between 8 and 13 years in girls and between 9 years 6 months and 13 years 6 months in boys [1, 2]. Recent data suggests that pubertal onset is occurring at earlier ages in girls, especially among ethnic minorities and those with higher body mass indices [3–10]. Therefore, it has been suggested to redefine the age of precocious puberty in non-Hispanic black girls to <6 years of age and to <7 years in all other girls [8]. It remains generally accepted that pubertal onset at less than 9 years remains precocious in boys. Significant controversy has risen from these recommendations, given the possible risk of delaying or missing the diagnosis of a pathologic cause of precocious puberty [11, 12]. Importantly, sexual development that occurs at a very young age or puberty that progresses asynchronously or at an accelerated tempo may indicate underlying pathology.

The prevalence of precocious puberty has been estimated to be at least 10–20-fold higher in girls compared with boys [13]. However, the likelihood of finding an organic cause of precocious puberty is much higher in boys than girls [13–16]. Neoplastic causes of precocious puberty are uncommon but nonetheless important etiologies of precocious sexual development, and prompt recognition of these rare presentations is paramount.

The intent of the current manuscript is to review the neoplastic and developmental causes of gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty and to share some of our clinical experience at the Children's Cancer Hospital of the University of Texas M D Anderson Cancer Center. We will not review gonadotropin-independent sexual precocity, such as seen with sex steroid production by primary adrenal or gonadal neoplasms. We will also discuss the potential effects of radiation therapy for childhood tumors on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Finally, we will broadly review specific endocrine considerations regarding the therapies available for height preservation in this unique patient population.

2. Diagnosis of Gonadotropin-Dependent Precocious Puberty

Gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty results from the premature activation of the HPG axis, which can occur directly from tumor involvement of the hypothalamus/pituitary or indirectly, such as seen with hydrocephalus (see below). The mechanisms that activate the HPG axis are poorly understood, but recent developments have contributed significantly to our understanding of pubertal onset and subsequent reproductive health. Among the most important recent discoveries has been the identification of kisspeptin, a ligand for the G-protein coupled receptor 54 [17–19]. The gene encoding kisspeptin (Kiss1) has been demonstrated to be mutated in some cases of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism [20, 21] and to be upregulated in some instances of precocious puberty [22–24]. It appears that kisspeptin expression is in part regulated by androgens and estrogens in a gender-specific manner [25]. Kisspeptin expression also appears to be influenced by leptin [26], which may help to explain the trend toward earlier pubertal onset among overweight youth.

A careful history (including timing/extent of pubertal changes, family history, and associated symptoms such as headaches and visual loss) in addition to a comprehensive physical examination (including past and current growth velocity as well as a detailed assessment of sexual maturation) are essential [27]. Gender-specific changes, such as bilateral increase in testicular volume in boys and breast development in girls, may suggest gonadotropin-dependent pubertal development. However, it is important to realize that these findings may be variable depending on etiology and may also be found in gonadotropin-independent sexual precocity [28, 29]. Chalumeau et al. has identified three predictors of CNS lesions in girls, including age < 6 years, estradiol > 100 pmol/L, and absence of pubic hair [12]. Distinguishing pubertal variants such as benign premature thelarche, adrenarche, and menarche from precocious puberty is imperative so that significant pathology is not missed.

A bone age (radiograph of the nondominant hand and wrist) is vital in the evaluation of sexual precocity, as it is expected to be advanced for chronologic age in cases of pathologic precocious puberty [30]. Skeletal age advancement in association with rapid progression of sexual maturation defines sexual precocity, but determining the exact etiology requires further evaluation.

The diagnosis of gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty is made by demonstrating a pubertal luteinizing hormone (LH) at baseline (specifically LH/follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) ratio > 0.2) [31] or in response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or GnRH analog (GnRHa) stimulation [32–40]. The agent used, dosing, and route of administration (intravenous or subcutaneous) vary between studies, making it difficult to set exact cutoff values, so these tests should always be interpreted in the clinical context of the child being evaluated and the test being performed.

At our center, our protocol is based upon that previously published by Garibaldi and colleagues [32], We draw baseline LH, FSH, and testosterone/estradiol levels (gender-dependent) followed by the subcutaneous administration of 20 micrograms/kg of leuprolide acetate (concentration of 1000 mcg/0.2 mL). LH and FSH samples are obtained at 60, 120, and 180 minutes after injection with testosterone/estradiol repeated at 180 minutes after injection.

The use of ultrasensitive assays for measuring LH is of utmost importance in interpreting the data [41, 42], but the basal LH level may not always reflect pubertal stage secondary to the cyclic changes in gonadotropin secretion depending on pubertal status [43]. It has been reported that GnRH-stimulated LH levels greater than 4.1 IU/L (using ICMA) in boys and 3.3 IU/L (using ICMA) in girls are suggestive of precocious puberty [42]. However, in girls, there was significant overlap between prepubertal and pubertal values. Nevertheless, an LH-predominant response to exogenous GnRH or GnRHa is anticipated in the child with sexual precocity that is driven by premature activation of the HPG axis.

If a pubertal LH level is demonstrated, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally indicated to look for a CNS lesion [44–46]. This is particularly true for very young patients (age ≤ 6) who present with gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty and boys, noting that the recommendation for routine CNS imaging in older otherwise asymptomatic girls remains controversial [46–49].

Tumors that overproduce human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) are also an important cause of precocious puberty in boys due to the cross-reaction of hCG with the LH receptor. Such tumors may be located centrally or peripherally (see further discussion below). Commonly, boys have less pronounced testicular enlargement secondary to lack of Sertoli cell stimulation from follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). Of importance, baseline and stimulated LH levels are prepubertal, but physical findings are consistent with gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty. Measurement of serum β-hCG is the initial diagnostic test of choice, and assessing β-hCG levels in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid may help differentiate tumor location. In addition to brain MRI to look for pinealomas or dysgerminomas, it is also important to look for lesions in the mediastinum, liver, and gonads. The work-up of an hCG-secreting tumor should include a staged and symptom-oriented approach to imaging of the brain, chest, liver, and gonads. Cyclic surges and declines of β-hCG in such tumors have been described, making repeat measurements often necessary in suspect cases [50]. For the purposes of this review, such cases are categorized as gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty because hCG is a gonadotropin and imparts a similar clinical presentation to gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty.

3. Central Nervous System (CNS) Tumors

CNS tumors will be discussed in order of overall frequency of occurrence in childhood. Though CNS tumors are relatively common childhood neoplasms, tumors presenting with precocious puberty are relatively uncommon [51]. A number of CNS tumors contributing to precocious puberty have been described. Commonly, these tumors are located in the sellar and/or suprasellar region of the brain, thereby directly disrupting the normal prepubertal inhibition of the HPG axis. Sometimes tumors distant from the sella may indirectly cause GnRH stimulation through pressure on the hypothalamic-pituitary region from concurrent hydrocephalus [52]. Table 1 summarizes the potential causes of gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty.

Table 1.

Causes of gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty.

| (i) Idiopathic |

| (ii) Central nervous system tumors (through direct or indirect effects on GnRH): |

| (1) Arachnoid cysts |

| (2) Craniopharyngiomas |

| (3) Ependymomas |

| (4) Germinomas (non-HCG secreting) |

| (5) Low-grade gliomas (juvenile pilocytic astrocytomas; optic pathway gliomas) |

| (iii) Paraneoplastic conditions (through the action of HCG on the LH receptor): |

| (1) Germ cell tumors: |

| (a) CNS |

| (b) Gonadal |

| (c) Hepatic |

| (d) Mediastinal (can occur in Klinefelter's syndrome) |

| (2) Hepatoblastoma |

| (iv) Developmental anomalies (through direct or indirect effects on GnRH): |

| (1) Arachnoid cysts |

| (2) Hydrocephalus |

| (3) Hypothalamic hamartomas |

| (v) Postirradiation (through direct effects on GnRH): |

| (1) Radiation therapy for childhood cancers (girls more susceptible) |

| (vi) Post-infectious, trauma, and bleed (through direct or indirect effects on GnRH): |

| (1) Sometimes associated with arachnoid cyst development |

GnRH, gonadotropin releasing hormone; HCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; LH, luteinizing hormone.

Generally, CNS tumors are classified based on primary morphology and tumor location in children. Symptoms and signs of a primary CNS neoplasm depend on the growth rate of the tumor, its location, and age of the child [53]. Clinical findings can be quite varied, ranging from signs of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) to localizing neurological signs and symptoms. Weight loss, macrocephaly, and growth failure may also suggest the presence of a CNS tumor [51].

Infratentorial tumors are located in the posterior fossa and include medulloblastoma, cerebellar astrocytoma, brain stem glioma, ependymoma, and atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors. These tumors commonly present with ataxia, cranial neuropathies, and signs of increased ICP, such as headaches and emesis. When precocious puberty presents in this setting, it is most likely secondary to increased ICP causing interference in the hypothalamic region.

Supratentorial tumors include suprasellar tumors such as craniopharyngiomas, gliomas, germinomas, pineal tumors, supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumors, and ependymomas [53]. These tumors commonly present with visual disturbances and signs of increased ICP as well as possible neuroendocrine dysfunction.

3.1. Low-Grade Gliomas

Most low-grade gliomas (LGG) in children are juvenile pilocytic astrocytomas (JPA) or diffuse fibrillary astrocytomas, while oligodendrogliomas, oligoastrocytomas, and mixed gliomas are much less common. JPAs are most often found in the cerebellar region, though they may also be in other CNS regions including the hypothalamus/optic pathway or the spinal cord. They comprise approximately 50%–60% of CNS tumors, with greater than 75% occurring during childhood [55]. The average age of diagnosis is 6.5 to 9 years and boys are more commonly affected [56]. Though JPAs are generally well circumscribed and slow growing, this indolent growth pattern contributes significantly to their associated morbidities. Metastases are uncommon, although tumors in the hypothalamic and periventricular regions are more likely to spread. Commonly, children with LGG present with headache and seizure, though precocious puberty may be among the initial manifestations (Figure 1).

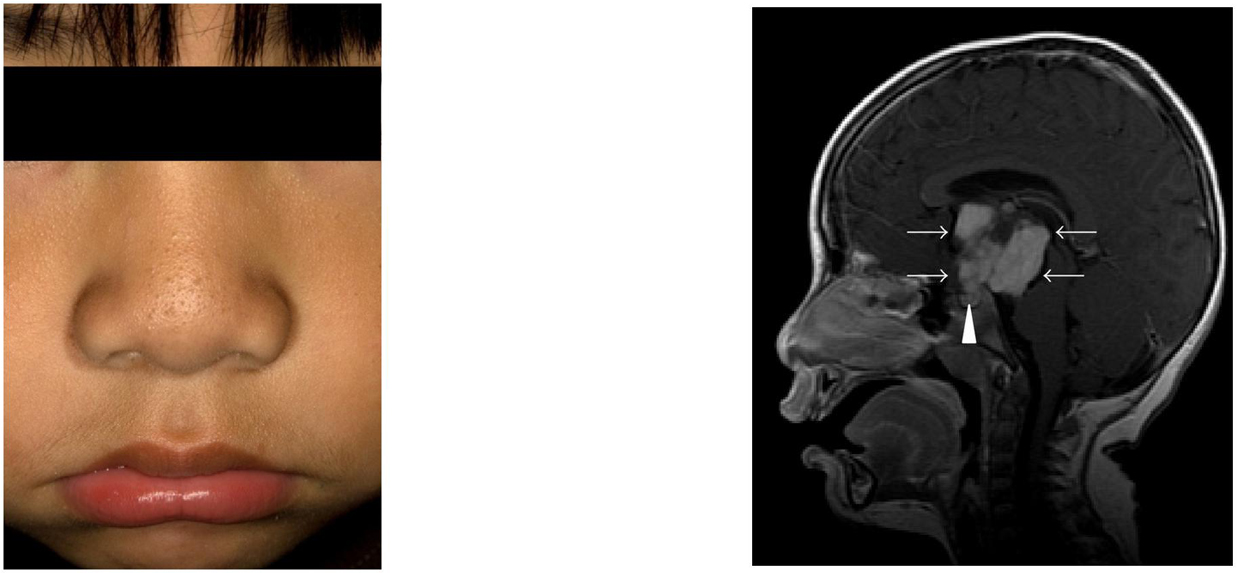

Figure 1.

(a) A 3-year-old male presented with Tanner II pubic hair, testicular enlargement (~6 mL bilaterally), facial hair, and acne. Laboratory evaluation was consistent with gonadotropin-dependent sexual precocity. (b) MRI revealed a large suprasellar mass (arrows) with both solid and cystic components. The normal pituitary (arrowhead) is also visualized. Pathology confirmed a juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma.

LGGs associated with the optic pathway are commonly found in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1). While at least 15% of patients with NF-1 develop optic pathway gliomas, approximately one-third of patients with optic pathway gliomas are subsequently found to have NF-1 [53]. NF-1 affects approximately one in 2500–3000 people [57–59]. It is an autosomal dominant neurocutaneous disorder with characteristic clinical findings, including café-au-lait macules with smooth borders (Figure 2), skinfold freckling, cutaneous neurofibromas, and iris hamartomas [60]. The clinical sequelae of NF-1 are due to inactivation of the tumor suppressor gene neurofibromin-1, which in turn normally inhibits the Ras gene, an important regulator of cell growth, differentiation, and survival [61, 62]. Upregulated Ras activity with or without a clear gene mutation may act in part through activation of the mTOR pathway [63–65]. Optic gliomas in association with NF-1 seem to contribute to precocious puberty through direct mass effect (Figure 2). The interested reader is referred to a recent comprehensive review of NF1 by Williams et al. [66].

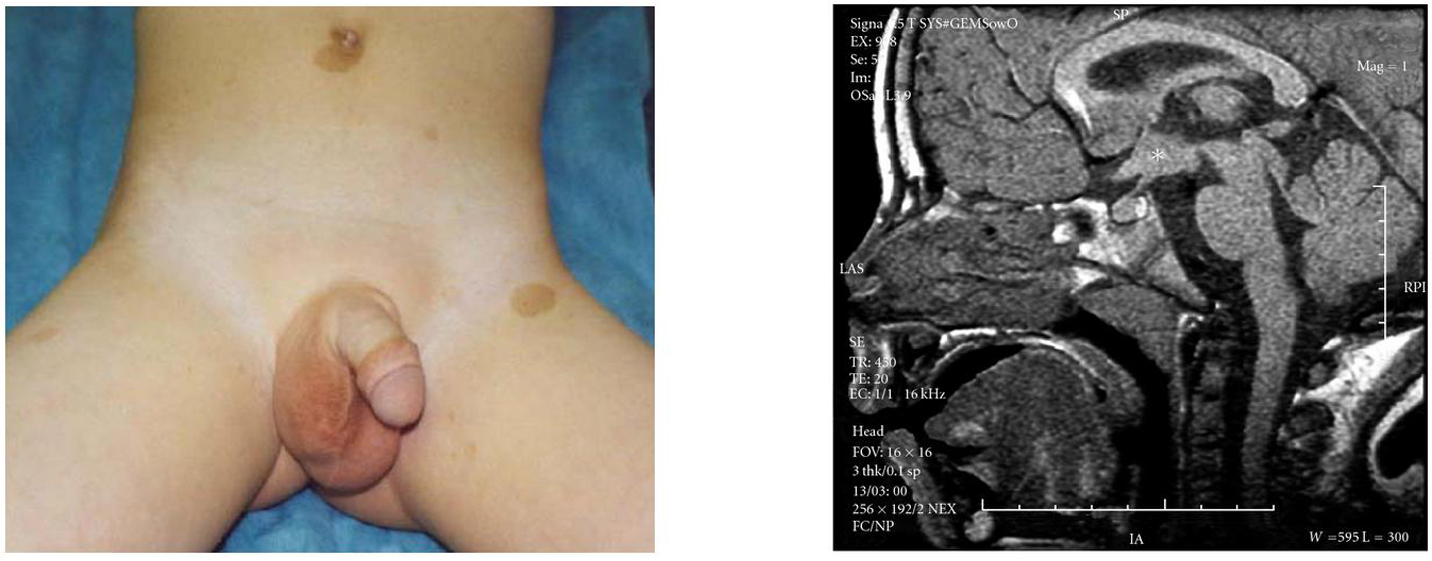

Figure 2.

(a) A 3-year-old male with neurofibromatosis type 1 (note classic café-au-lait macules) presented with a history of growth acceleration and testicular enlargement. Bone age was advanced by 6 years. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation confirmed a diagnosis of gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty, with a peak luteinizing hormone level of 20.9 mIU/mL. (b). MRI demonstrated a large optic pathway glioma (asterisk). (Figures obtained with permission [54].)

The diagnosis of LGGs is confirmed through biopsy and histologic classification. Treatment of LGGs should be individualized depending on the location and clinical sequelae of the tumor, in addition to the overall clinical context (i.e., whether or not the child has NF1). With cerebellar JPAs, surgical resection is often curative. Generally, even those with incomplete resection have excellent long-term progression-free survival [53]. Chemotherapy is usually recommended for symptomatic or progressive tumors with the intention of delaying or avoiding radiotherapy. Further, it is recommended that surgical resection be reserved only for those with significant extension of the tumor, disfiguring proptosis, and/or rapid clinical deterioration [67].

3.2. Ependymomas

Ependymomas tend to arise insidiously, and despite their predilection towards the lateral posterior fossa, they often cause obstructive hydrocephalus. Generally, these tumors are slow growing and well circumscribed. Ependymomas account for ~10% of CNS tumors in children [68]. The mean age at diagnosis is 3 years, with 50% being diagnosed prior to 5 years of age [69]. Boys are affected approximately 1.4 times more often than girls. Since greater than 70% of ependymomas arise from the posterior fossa, the signs at presentation are often a result of tumor-induced hydrocephalus [69]. This obstructive hydrocephalus may in turn lead to distinct effects on the hypothalamic region (Figure 3), including precocious pubertal onset.

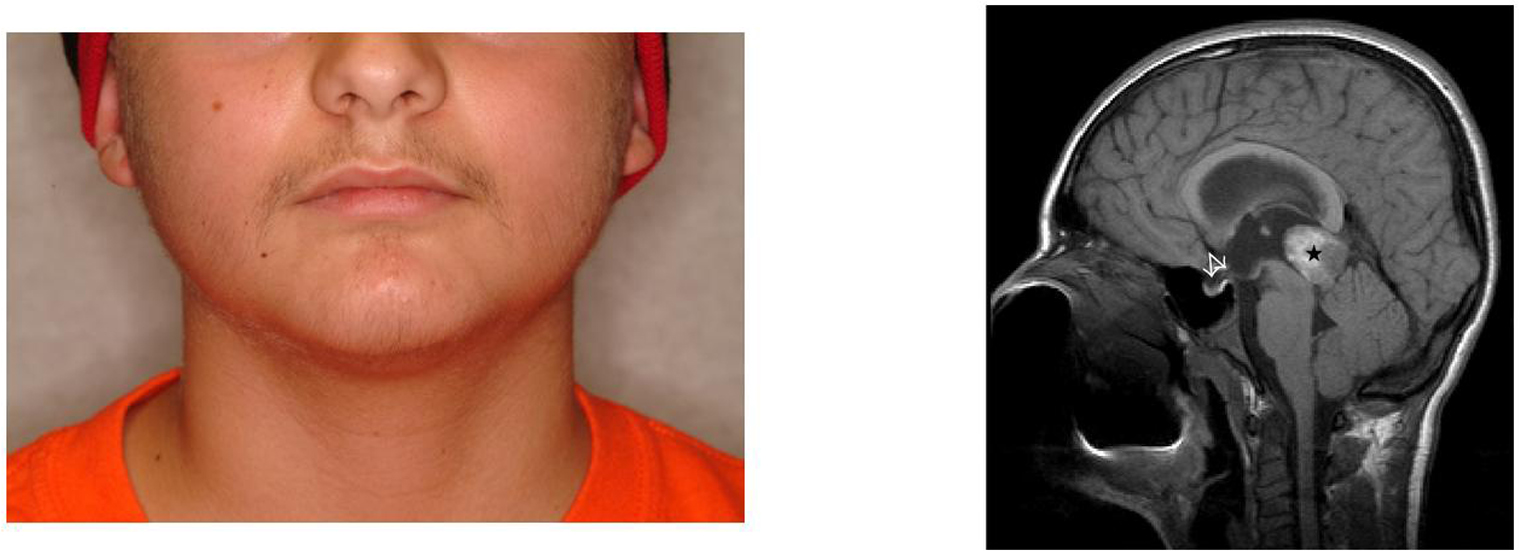

Figure 3.

(a) A 10-year-old male presented with significant facial and pubic hair growth, deepening voice, and minimal testicular enlargement (5 mL bilaterally). Laboratory evaluation showed a markedly elevated β-hCG, pubertal testosterone, and suppressed gonadotropin levels, consistent with hCG-mediated sexual precocity. (b) MRI revealed a large pineal mass (star). Note the effects of tumor-induced hydrocephalus on the hypothalamic-pituitary unit (arrows). Pathology revealed a mixed germ cell tumor and the patient had a complete response to therapy. He entered endogenous puberty normally and has a final height of 68 inches (midparental height 71 inches).

For ependymomas, total resection is the optimal therapy, which is more easily accomplished with supratentorial ependymomas [69]. The role of adjunct radiotherapy in children >3 years is well established, but it generally is not considered in younger children secondary to the potential effects of radiation on the developing brain [70]. Furthermore, ependymomas appear to be fairly resistant to chemotherapeutic regimens. However, there is renewed interest in using local radiotherapy in children as young as 1 year who have infratentorial tumors not amenable to surgical removal [71]. One review of prognostic factors shows that younger age appears to be the most important factor influencing survival [72].

3.3. Pineal Tumors

Pineal tumors include germ cell tumors, pineal parenchymal tumors, and glial tumors. These tumors comprise as much as 7% of CNS tumors in childhood [73]. The pineal gland is located adjacent to the brain stem and cerebral aqueduct, and tumors arising in this location may cause obstructive hydrocephalus (Figure 3). Loss of upward gaze (Parinaud's syndrome) may be seen secondary to brainstem compression. Dissemination is found in approximately 25% of patients at time of diagnosis [73]. Precocious puberty may occur with these tumors from either tumor-induced hydrocephalus or through gonadotropin secretion in the case of germ cell tumors (Figure 3; also see section on hCG-secreting tumors) [74, 75].

With pineal tumors, biopsy and histologic classification of tumor type is important prior to starting definitive therapy, because radiologic appearance alone will not define the type of pineal lesion present [73, 76]. The location of these tumors makes complete surgical resection quite difficult, necessitating adjunctive radiotherapy and chemotherapy, with variable long-term outcomes reported [53].

3.4. Craniopharyngioma

Craniopharyngiomas are slowly growing tumors of the sellar region with insidious onset [77, 78]. At the time of diagnosis, most patients have both neurologic and endocrine signs and symptoms related to disruption of hypothalamic-pituitary function and increased ICP/mass effect [77, 78]. These tumors account for 5% of CNS tumors and the majority of sellar tumors diagnosed in childhood [79]. They have a bimodal distribution with peak incidences from 5–14 years and again from 65–74 years of age [78, 80–82]. While the endocrine manifestations usually involve varying degrees of hypopituitarism, precocious puberty may also occur [83, 84]. The growth spurt typically expected with precocious puberty may be masked by concomitant growth hormone deficiency [84]. Computed tomography is helpful to identify the pathognomonic calcification that is a radiologic hallmark of craniopharyngioma, but MRI is preferred secondary to its superiority in detailing anatomy and tumor extent [77, 78].

Total surgical resection of craniopharyngiomas is associated with significant morbidity (including but not limited to hypothalamic obesity, panhypopituitarism, and altered neuropsychological profile) and mortality risk (up to 10%) [85–87]. Recurrence, even with complete resection, occurs in as many as 15% of these patients [78] and is associated with an even higher morbidity and mortality risk [88, 89]. Selective debulking along with adjunctive radiotherapy may be a more appropriate approach in these children [85].

4. Other Central Nervous System Lesions

4.1. Hypothalamic Hamartomas

Hypothalamic hamartomas are nonneoplastic developmental lesions that are usually histologically normal in appearance, but ectopic in position [90]. They are composed of heterotopic grey matter, neurons, and glial cells usually located at the base of the third ventricle, near the tuber cinereum or mammillary bodies. Hypothalamic hamartomas have a typical isointense radiographic appearance on MRI (Figure 4). They are classified as pedunculated or sessile, depending on the width of attachment to the tuber cinereum and their pattern of growth, namely intra- or extraparenchymal [91, 92]. These lesions are believed to cause precocious puberty (Figure 4) through endogenous pulsatile release of GnRH, either independently or in concert with the GnRH-secreting neurons of the hypothalamus [93]. It has also been suggested that precocious puberty may be caused through the indirect actions of glial factors, including transforming growth factor alpha, that stimulate GnRH secretion from the hypothalamus [94, 95]. Removal of the hamartoma does not prevent or inhibit further pubertal development in some patients. In these patients, secondary activation of astroglial cells in the surrounding hypothalamic tissue may cause increased GnRH secretion, thereby inducing precocious puberty [94–96].

Figure 4.

(a) A 4-year-old female presented with Tanner III-IV breast development and bone age advancement to 11 years of age. Leuprolide stimulation (stimulated luteinizing hormone of 28 mIu/mL) confirmed gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty. (b) MRI revealed an isointense mass (arrow) consistent with the diagnosis of a pedunculated hypothalamic hamartoma. This young girl's puberty has been adequately suppressed with depot leuprolide without further bone age advancement, pubertal development, neurologic sequelae, or mass changes on serial MRIs.

In patients with hamartomas, the classic triad of precocious puberty, developmental delay, and seizures, most notably gelastic ("laughing") seizures, is well described. Patients with hypothalamic hamartoma usually present at <4 years of age with precocious puberty [97, 98]. Precocious puberty is found in 33%–85% of patients with a hypothalamic hamartoma, many of whom also develop seizures [99]. It is a rare condition with a prevalence from 1 : 50,000–100,000 [100]. Pedunculated hamartomas are more likely to be associated with precocious puberty while sessile hamartomas are more likely to be associated with seizures [100, 101]. Generally, the presentation is more severe in younger patients and tends to progress towards a debilitating seizure disorder with marked developmental delay, while older patients tend to have a less severe seizure disorder and less developmental impairment.

Hypothalamic hamartomas are typically sporadic but may also be associated with the Pallister Hall Syndrome (PHS) [102]. PHS is an autosomal dominant syndrome with anomalies including hypothalamic hamartoma, pituitary abnormalities (including aplasia/dysplasia and/or hypopituitarism), imperforate anus, and polydactyly [103, 104]. PHS is due to mutations of the zinc-finger transcription factor gene GLI3 on chromosome 7p13. GLI3 has been demonstrated to have a role in sonic hedgehog-mediated brain development. Disruption of this gene or associated genes may explain some cases of hypothalamic hamartoma [105]. A number of other candidate genes are being investigated for potential roles in hypothalamic hamartoma formation and its clinical sequelae [106].

Treatment of hypothalamic hamartomas varies depending upon the patient's symptoms and appearance of the tumor. Generally, precocious puberty can be adequately treated with GnRH analog therapy, whereas treating the associated seizures can be much more challenging [107]. Téllez-Zenteno et al. have recently reviewed the various surgical and nonsurgical approaches to the treatment of hypothalamic hamartomas [108]. The transcallosal surgical approach has shown to be the most effective for seizure control, although a number of other therapies, including stereotactic radiosurgery, have shown promise [108].

4.2. Arachnoid Cysts

Arachnoid cysts are relatively uncommon intracranial lesions, usually developmental in origin, but they may also develop after infection, trauma, or hemorrhage [109]. Furthermore, arachnoid cysts have also been described in association with hypothalamic hamartomas and tuberous sclerosis [110, 111]. Neurologic and visual field disturbances are common. Arachnoid cysts are also commonly associated with other midline defects and optic nerve hypoplasia [109]. When located in the suprasellar region, endocrine findings are common, including gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty. A number of cases have reported precocious puberty along with pituitary hormone deficits as well as neurologic findings, specifically the bobble-head doll phenomenon (rhythmic to-and-fro bobbling of the head and trunk) [112–115]. Interestingly, delayed puberty has also been reported with arachnoid cysts and other suprasellar lesions [116, 117]. Arachnoid cysts can be successfully managed with stereotactic ventriculocystostomy [113, 118].

4.3. hCG-Producing Tumors

Germ cell tumors can produce excessive hCG, which causes precocious puberty, almost exclusively in males, via cross-reaction with the LH receptor. Typically arising from the brain (Figure 3), mediastinum (Figure 5), or gonads, these tumors are characterized based on histologic differences. Regardless of locale, the child may present with manifestations typical of isosexual precocious puberty, but with suppressed basal and/or stimulated LH levels. Girls with hCG-secreting tumors uncommonly present with precocious puberty secondary to the requirement for both LH and FSH effects at the ovary for pubertal onset [119]. Intracranial hCG-secreting tumors may present with isosexual precocious puberty, irrespective of gender, secondary to disinhibition of GnRH, weak FSH effect (as a consequence of massive hCG secretion), and cosecretion of estradiol by some dysgerminomas [120, 121]. There is a well-recognized association of mediastinal hCG-secreting germ cell tumors in patients with Klinefelter's syndrome [122, 123].

Figure 5.

A 4-year-old male with a history of asthma presented with complaints of

pubertal changes (pubic hair growth, erections, sexual behaviors, acne,

deepening of the voice, accelerated linear growth, and increased muscle

mass). (a) On examination, he had an enlarged penis and Tanner III-IV

pubic hair; testes were minimally enlarged (b) Bone age was 10 years and

laboratory evaluation revealed a total testosterone of 673 ng/dL (normal

≤5), β-hCG of 22.9 mIU/mL (normal ≤1.0), and

undetectable gonadotropin levels, consistent with hCG-mediated sexual

precocity. (c) CT chest revealed a  cm

heterogeneous mass located in the anterior mediastinum (arrows). This lesion

was resected and confirmed to be a mature cystic teratoma. After surgery, the

patient's labs normalized, and he remains clinically prepubertal at a

chronological age of 9 years and bone age of 13 years.

cm

heterogeneous mass located in the anterior mediastinum (arrows). This lesion

was resected and confirmed to be a mature cystic teratoma. After surgery, the

patient's labs normalized, and he remains clinically prepubertal at a

chronological age of 9 years and bone age of 13 years.

5. Radiation Related Precocious Puberty

Cranial irradiation is a commonly used modality for the treatment of primary CNS tumors, and it can also be used in the adjunctive treatment of other childhood malignancies. The effects of radiotherapy on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis are variable and may evolve over a prolonged period of time. Somatotrophs are the anterior pituitary cell type most sensitive to irradiation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis followed by the gonadotrophs, corticotrophs, and thyrotrophs [124].

Lower doses (18–24 Gray) of radiotherapy are often associated with precocious puberty in girls [125–127], whereas doses higher than 25 Gray can affect both sexes, with younger age at radiotherapy conferring a higher risk of precocious puberty (Figure 6) [127–129]. Furthermore, patients who develop precocious puberty following doses of 30 Gray or more have a significant risk of ultimately developing gonadotropin deficiency, while those who receive doses in excess of 50 Gray are at increased risk of delayed puberty (secondary to gonadotropin deficiency) [130–132].

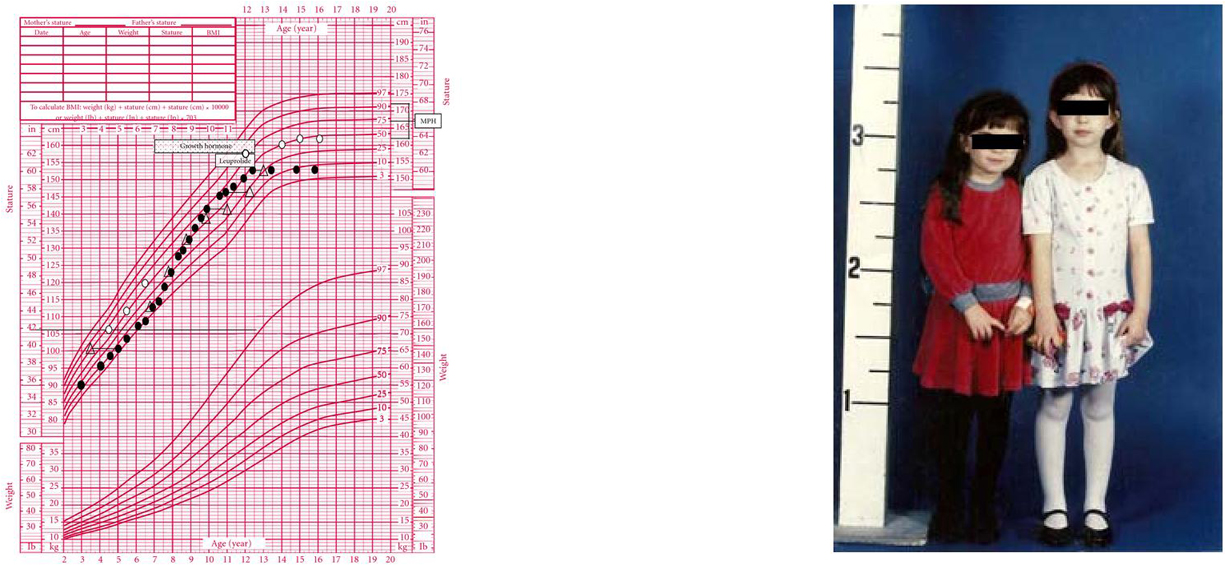

Figure 6.

(a) Growth chart of a girl (solid circles) with a history of locally advanced retinoblastoma status post right eye enucleation, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy (39.6 Gy in 35 fractions) to the orbit, completed at the age of 17 months. Bone ages are represented by open triangles. She was diagnosed with growth hormone (GH) deficiency and then gonadotropin-dependent sexual precocity and treated with GH and depot leuprolide, respectively. The patient had menarche at age 8 and achieved a final height of 60 inches, well below mid-parental height (MPH). (b) The patient's identical twin sister (open circles) was already significantly taller by the age of 5 years. She had menarche at age 12 and achieved a final adult height of 63.75 inches.

A recent report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study found a significantly increased risk of both early and late menarche in cancer survivors when compared with their siblings [133]. In this study, radiotherapy >50 Gray and age of treatment ≤4 years conferred a higher risk for early menarche. While lower doses of radiotherapy also increased the odds of early menarche, statistical significance was not demonstrated. Another report of female acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) survivors demonstrated that those who were treated with cranial radiotherapy had higher rates of early menarche and those treated with craniospinal radiotherapy had higher rates of both early and late menarche when compared to those treated with chemotherapy alone [134]. This study also found an increased risk of early menarche among those diagnosed at <5 years of age.

In childhood cancer survivors, the presentation of sexual precocity can be subtle, the definitions of normal puberty may not apply, and the diagnosis may not be straightforward. For example, patients who develop precocious puberty after irradiation may also have concomitant growth hormone deficiency, which in turn can mask pubertal growth acceleration and bone age advance, in turn delaying the diagnosis of sexual precocity (Figure 6) [135, 136]. Importantly, testicular volume in boys who are childhood cancer survivors may not be reliable in the identification of pubertal onset, and so a high index of suspicion and measurement of gonadotropin and testosterone levels in boys previously treated with radiation and chemotherapy is paramount [137, 138].

6. Treatment of Gonadotropin-Dependent Precocious Puberty-Endocrine Considerations

The appropriate treatment of gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty is initially contingent on correctly identifying the etiology. GnRHa therapy has been demonstrated to be quite effective at stalling puberty and preserving adult height (particularly when started at <6 years of age) in children with precocious puberty due to premature activation of the HPG axis [139]. In children with hCG-secreting tumors, the precocious puberty is best addressed by treating the underlying tumor, although the natural history of endogenous puberty in such children, who in our experience tend to have markedly advanced skeletal maturation, remains poorly characterized.

The treatment of brain lesions contributing to precocious puberty is tumor dependent and is also dependent on a number of other factors, including age, comorbidities, and location of the tumor. Importantly, the endocrinologist should carefully evaluate the remainder of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis prior to definitive therapy and regularly after therapy is complete [140]. Treatment of pituitary hormone deficiencies should be undertaken as clinically indicated, recognizing that the diagnosis of clinically important endocrinopathies, such as central hypothyroidism, may be difficult to make in this population.

Children diagnosed with a brain tumor prior to 4 years of age and those who receive radiation potentially affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary axis are at highest risk of adult short stature [141]. Helping such children who develop sexual precocity achieve a normal adult height may be difficult, and multimodality hormonal therapy may need to be considered. Commonly, these children are not diagnosed until a later age and/or may have such an advancement of skeletal maturity that GnRHa therapy alone may not salvage adult height. In these situations, the use of growth hormone and/or aromatase inhibitor therapy may be considered but remains largely unstudied in this population. The addition of growth hormone to GnRHa therapy has shown variable responses in height gain dependent on duration of therapy [142–144]. Among children who received spinal radiation therapy, age at treatment appears to influence adult height most, and boys seem to be less responsive to growth hormone therapy than girls [145]. Aromatase inhibitors have been shown to increase predicted adult height in normal boys treated with growth hormone while allowing normal pubertal progression [146–148]. Our initial clinical experience has demonstrated an increased predicted adult height with the use of growth hormone and/or aromatase inhibitors, but this is an area that needs to be researched further via prospective clinical trials in terms of long-term safety and efficacy.

7. Conclusion

When evaluating children with precocious puberty, possible neoplastic, developmental, and iatrogenic causes should be considered in the differential diagnosis, particularly in boys and in childhood cancer survivors. Through prompt evaluation and treatment, long-term sequelae, specifically short stature and possible impaired quality of life, may be avoided. A heightened awareness of the neoplastic causes of gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty and vigilance in the evaluation of children presenting with precocious puberty are of utmost importance in order to avoid missing important pathology.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviations

LH: Luteinizing hormone

β-HCG: Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin

GnRH: Gonadotropin releasing hormone

PHS: Pallister-Hall Syndrome

ICP: Intracranial pressure

LGG: Low-grade glioma

JPA: Juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma

NF-1: Neurofibromatosis type 1

TSH: Thyroid stimulating hormone

ACTH: Adrenocorticotropin hormone

AVP: Arginine Vasopressin

HPG: Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

Contributor Information

Matthew D Stephen, Email: mstephen@swmail.sw.org.

Peter E Zage, Email: pezage@mdanderson.org.

Steven G Waguespack, Email: swagues@mdanderson.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the insightful review of this paper by Drs. Patrick Brosnan, Emily Walvoord, and Anita Ying.

References

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1969;44(235):291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1970;45(239):13–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz PB. Link between body fat and the timing of puberty. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3, supplement):S208–S217. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euling SY, Herman-Giddens ME, Lee PA, Selevan SG, Juul A, Sørensen TIA, Dunkel L, Himes JH, Teilmann G, Swan SH. Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3, supplement):S172–S191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumlea WC, Schubert CM, Roche AF, Kulin HE, Lee PA, Himes JH, Sun SS. Age at menarche and racial comparisons in US girls. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):110–113. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Mendola P, Buck GM. Ethnic differences in the presence of secondary sex characteristics and menarche among US girls: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Pediatrics. 2002;110(4):752–757. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SS, Schubert CM, Chumlea WC, Roche AF, Kulin HE, Lee PA, Himes JH, Ryan AS. National estimates of the timing of sexual maturation and racial differences among US children. Pediatrics. 2002;110(5):911–919. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz PB, Oberfield SE. Reexamination of the age limit for defining when puberty is precocious in girls in the United States: implications for evaluation and treatment. Pediatrics. 1999;104(4):936–941. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.4.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Giddens ME, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, Bourdony CJ, Bhapkar MV, Koch GG, Hasemeier CM. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the pediatric research in office settings network. Pediatrics. 1997;99(4):505–512. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield RL, Lipton RB, Drum ML. Thelarche, pubarche, and menarche attainment in children with normal and elevated body mass index. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):84–88. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midyett LK, Moore WV, Jacobson JD. Are pubertal changes in girls before age 8 benign? Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):47–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalumeau M, Chemaitilly W, Trivin C, Adan L, Bréart G, Brauner R. Central precocious puberty in girls: an evidence-based diagnosis tree to predict central nervous system abnormalities. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):61–67. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teilmann G, Pedersen CB, Jensen TK, Skakkebæk NE, Juul A. Prevalence and incidence of precocious pubertal development in Denmark: an epidemiologic study based on national registries. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1323–1328. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges NA, Christopher JA, Hindmarsh PC, Brook CGD. Sexual precocity: sex incidence and aetiology. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1994;70(2):116–118. doi: 10.1136/adc.70.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisternino M, Arrigo T, Pasquino AM, Tinelli C, Antoniazzi F, Beduschi L, Bindi G, Borrelli P, De Sanctis V, Farello G, Galluzzi F, Gargantini L, Lo Presti D, Sposito M, Tato L. Etiology and age incidence of precocious puberty in girls: a multicentric study. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;13(1, supplement):695–701. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2000.13.s1.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sanctis V, Corrias A, Rizzo V, Bertelloni S, Urso L, Galluzzi F, Pasquino AM, Pozzan G, Guarneri MP, Cisternino M, De Luca F, Gargantini L, Pilotta A, Sposito M, Tonini G. Etiology of central precocious puberty in males: the results of the Italian Study Group for physiopathology of puberty. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;13(1, supplement):687–693. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2000.13.s1.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotani M, Detheux M, Vandenbogaerde A, Communi D, Vanderwinden JM, Le Poul E, Brézillon S, Tyldesley R, Suarez-Huerta N, Vandeput F, Blanpain C, Schiffmann SN, Vassart G, Parmentier M. The metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes kisspeptins, the natural ligands of the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR54. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(37):34631–34636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtaki T, Shintani Y, Honda S, Matsumoto H, Hori A, Kanehashi K, Terao Y, Kumano S, Takatsu Y, Masuda Y, Ishibashi Y, Watanabe T, Asada M, Yamada T, Suenaga M, Kitada C, Usuki S, Kurokawa T, Onda H, Nishimura O, Fujino M. Metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes peptide ligand of a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2001;411(6837):613–617. doi: 10.1038/35079135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir AI, Chamberlain L, Elshourbagy NA, Michalovich D, Moore DJ, Calamari A, Szekeres PG, Sarau HM, Chambers JK, Murdock P, Steplewski K, Shabon U, Miller JE, Middleton SE, Darker JG, Larminie CGC, Wilson S, Bergsma DJ, Emson P, Faull R, Philpott KL, Harrison DC. AXOR12, a novel human G protein-coupled receptor, activated by the peptide KiSS-1. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(31):28969–28975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roux N, Genin E, Carel JC, Matsuda F, Chaussain JL, Milgrom E. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(19):10972–10976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834399100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Thresher RR, Acierno JS, Shagoury JK, Bo-Abbas Y, Kuohung W, Schwinof KM, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Dixon J, Kaiser UB, Slaugenhaupt SA, Gusella JF, O'Rahilly S, Carlton MBL, Crowley WF, Aparicio SAJR, Colledge WH. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(17):1614–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries L, Shtaif B, Phillip M, Gat-Yablonski G. Kisspeptin serum levels in girls with central precocious puberty. Clinical Endocrinology. 2009;71(4):524–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teles MG, Bianco SDC, Brito VN, Trarbach EB, Kuohung W, Xu S, Seminara SB, Mendonca BB, Kaiser UB, Latronico AC. Brief report: a GPR54-activating mutation in a patient with central precocious puberty. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(7):709–715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira LG, Noel SD, Silveira-Neto AP, Abreu AP, Brito VN, Santos MG, Bianco SD, Kuohung W, Xu S, Gryngarten M, Escobar ME, Arnhold IJ, Mendonca BB, Kaiser UB, Latronico AC. Mutations of the KISS1 gene in disorders of puberty. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95(5):2276–2280. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley AE, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Kisspeptin signaling in the brain. Endocrine Reviews. 2009;30(6):713–743. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano JM, Roa J, Luque RM, Dieguez C, Aguilar E, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M. KiSS-1/kisspeptins and the metabolic control of reproduction: physiologic roles and putative physiopathological implications. Peptides. 2009;30(1):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carel JC, Léger J. Clinical practice. Precocious puberty. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:2366–2377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0800459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugster EA. Peripheral precocious puberty: causes and current management. Hormone Research. 2009;71(1):64–67. doi: 10.1159/000178041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivin C, Couto-Silva AC, Sainte-Rose C, Chemaitilly W, Kalifa C, Doz F, Zerah M, Brauner R. Presentation and evolution of organic central precocious puberty according to the type of CNS lesion. Clinical Endocrinology. 2006;65(2):239–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar A, Linder B, Sobel EH, Saenger P, DiMartino-Nardi J. Bayley-Pinneau method of height prediction in girls with central precocious puberty: correlation with adult height. Journal of Pediatrics. 1995;126(6):955–958. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(95)70221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supornsilchai V, Wacharasindhu S, Aroonparkmongkol S, Hiranrat P, Srivuthana S. Basal luteinizing hormone/follicle stimulating hormone ratio in diagnosis of central precocious puberty. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2003;86(2, supplement):S145–S151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi LR, Aceto T Jr., Weber C, Pang S. The relationship between luteinizing hormone and estradiol secretion in female precocious puberty: evaluation by sensitive gonadotropin assays and the leuprolide stimulation test. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1993;76(4):851–856. doi: 10.1210/jc.76.4.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez L, Potau N, Zampolli M, Virdis R, Gussinyé M, Carrascosa A, Saenger P, Vicens-Calvet E. Use of leuprolide acetate response patterns in the early diagnosis of pubertal disorders: comparison with the gonadotropin-releasing hormone test. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1994;78(1):30–35. doi: 10.1210/jc.78.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poomthavorn P, Khlairit P, Mahachoklertwattana P. Subcutaneous gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (triptorelin) test for diagnosing precocious puberty. Hormone Research. 2009;72(2):114–119. doi: 10.1159/000232164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houk CP, Kunselman AR, Lee PA. The diagnostic value of a brief GnRH analogue stimulation test in girls with central precocious puberty: a single 30-minute post-stimulation LH sample is adequate. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;21(12):1113–1118. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2008.21.12.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito VN, Latronico AC, Arnhold IJP, Mendonça BB. Update on the etiology, diagnosis and therapeutic management of sexual precocity. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia e Metabologia. 2008;52(1):18–31. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302008000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zevenhuijzen H, Kelnar CJH, Crofton PM. Diagnostic utility of a low-dose gonadotropin-releasing hormone test in the context of puberty disorders. Hormone Research. 2004;62(4):168–176. doi: 10.1159/000080324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert KL, Wilson DM, Bachrach LK, Anhalt H, Habiby RL, Olney RC, Hintz RL, Neely EK. A single-sample, subcutaneous gonadotropin-releasing hormone test for central precocious puberty. Pediatrics. 1996;97(4):517–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo A, Richards GE, Busey S, Michaels SE. A simplified gonadotrophin-releasing hormone test for precocious puberty. Clinical Endocrinology. 1995;42(6):641–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb02692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacharasindhu S, Srivuthana S, Aroonparkmongkol S, Shotelersuk V. A cost-benefit of GnRH stimulation test in diagnosis of central precocious puberty (CPP) Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2000;83(9):1105–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi LR, Picco P, Magier S, Chevli R, Aceto T. Serum luteinizing hormone concentrations, as measured by a sensitive immunoradiometric assay, in children with normal, precocious or delayed pubertal development. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1991;72(4):888–898. doi: 10.1210/jcem-72-4-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Resende EAMR, Lara BHJ, Reis JD, Ferreira BP, Pereira GA, Borges MF. Assessment of basal and gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated gonadotropins by immunochemiluminometric and immunofluorometric assays in normal children. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92(4):1424–1429. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbach MM. The neuroendocrinology of human puberty revisited. Hormone Research. 2002;57(2, supplement):2–14. doi: 10.1159/000058094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SM, Kumar Y, Cody D, Smith C, Didi M. The gonadotrophins response to GnRH test is not a predictor of neurological lesion in girls with central precocious puberty. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;18(9):849–852. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2005.18.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornreich L, Horev G, Blaser S, Daneman D, Kauli R, Grunebaum M. Central precocious puberty: evaluation by neuroimaging. Pediatric Radiology. 1995;25(1):7–11. doi: 10.1007/BF02020830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope R. Gonadotrophin-dependant precocious puberty and occult intracranial tumors: which girls should have neuro-imaging? Journal of Pediatrics. 2003;143(4):426–427. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00492-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoforidis A, Stanhope R. Girls with gonadotrophin-dependent precocious puberty: do they all deserve neuroimaging? Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;18(9):843–844. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2005.18.9.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope R. Central precocious puberty and occult intracranial tumours. Clinical Endocrinology. 2001;54(3):287–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz P. Precocious puberty in girls and the risk of a central nervous system abnormality: the elusive search for diagnostic certainty. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):139–141. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe J, Calaminus G, Vorhoff W, Engelbrecht V, Hauffa BP, Göbel U. Sexual precocity and recurrent β-human chorionic gonadotropin upsurges preceding the diagnosis of a malignant mediastinal germ-cell tumor in a 9-year-old boy. Annals of Oncology. 2002;13(6):975–977. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilne S, Collier J, Kennedy C, Koller K, Grundy R, Walker D. Presentation of childhood CNS tumours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncology. 2007;8(8):685–695. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josan VA, Timms CD, Rickert C, Wallace D. Cerebellar astrocytoma presenting with precocious puberty in a girl. Case report. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2007;107(1):66–68. doi: 10.3171/PED-07/07/066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer RJ, MacDonald T, Vezina G. Central Nervous System Tumors. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2008;55(1):121–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walvoord EC, Waguespack SG, Pescovitz OH. In: Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 3. chapter 92. Becker KL, editor. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa, USA; 2001. Precocious and delayed puberty. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JW, Pollack IF. Cerebellar astrocytomas in children. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 1996;28(2-3):223–231. doi: 10.1007/BF00250201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaney SM, Kun L, Hunter J, In: Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 5th. Poplack, Pizzo P, editor. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa, USA; 2005. Tumors of the central nervous system; pp. 786–864. [Google Scholar]

- Huson SM, Harper PS, Compston DAS. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. A clinical and population study in south-east Wales. Brain. 1988;111(6):1355–1381. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.6.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson SM, Compston DAS, Clark P, Harper PS. A genetic study of von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis in south east Wales. I prevalence, fitness, mutation rate, and effect of parental transmission on severity. Journal of Medical Genetics. 1989;26(11):704–711. doi: 10.1136/jmg.26.11.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann DH, Aylsworth A, Carey JC, Korf B, Marks J, Pyeritz RE, Rubenstein A, Viskochil D. The diagnostic evaluation and multidisciplinary management of neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(1):51–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young H, Hyman S, North K. Neurofibromatosis 1: clinical review and exceptions to the rules. Journal of Child Neurology. 2002;17(8):613–621. doi: 10.1177/088307380201700812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karajannis M, Allen JC, Newcomb EW. Treatment of pediatric brain tumors. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2008;217(3):584–589. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listernick R, Ferner RE, Liu GT, Gutmann DH. Optic pathway gliomas in neurofibromatosis-1: controversies and recommendations. Annals of Neurology. 2007;61(3):189–198. doi: 10.1002/ana.21107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brems H, Beert E, de Ravel T, Legius E. Mechanisms in the pathogenesis of malignant tumours in neurofibromatosis type 1. The Lancet Oncology. 2009;10(5):508–515. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner M, Hanneder M, Siegel N, Valli A, Fuchs C, Hengstschläger M. The mTOR pathway and its role in human genetic diseases. Mutation Research. 2008;659(3):284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira S, Barkan B, Fridman E, Kloog Y, Stein R. The tumor suppressor neurofibromin confers sensitivity to apoptosis by Ras-dependent and Ras-independent pathways. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2007;14(5):895–906. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams VC, Lucas J, Babcock MA, Gutmann DH, Bruce B, Maria BL. Neurofibromatosis type 1 revisited. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):124–133. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm H. Primary optic nerve tumours. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2009;22(1):11–18. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32831fd9f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JC, Siffert J, Hukin J. Clinical manifestations of childhood ependymoma: a multitude of syndromes. Pediatric Neurosurgery. 1998;28(1):49–55. doi: 10.1159/000028619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejat F, El Khashab M, Rutka JT. Initial management of childhood brain tumors: neurosurgical considerations. Journal of Child Neurology. 2008;23(10):1136–1148. doi: 10.1177/0883073808321768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little AS, Sheean T, Manoharan R, Darbar A, Teo C. The management of completely resected childhood intracranial ependymoma: the argument for observation only. Child's Nervous System. 2009;25(3):281–284. doi: 10.1007/s00381-008-0799-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimino M, Giangaspero F, Garrè ML, Genitori L, Perilongo G, Collini P, Riva D, Valentini L, Scarzello G, Poggi G, Spreafico F, Peretta P, Mascarin M, Modena P, Sozzi G, Bedini N, Biassoni V, Urgesi A, Balestrini MR, Finocchiaro G, Sandri A, Gandola L. Salvage treatment for childhood ependymoma after surgery only: pitfalls of omitting "at once" adjuvant treatment. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2006;65(5):1440–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburrini G, D'Ercole M, Pettorini BL, Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Di Rocco C. Survival following treatment for intracranial ependymoma: a review. Child's Nervous System. 2009;25(10):1303–1312. doi: 10.1007/s00381-009-0874-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea AD, Packer RJ, Rorke LB. et al. Pineocytomas of childhood. A reappraisal of natural history and response to therapy. Cancer. 1987;59(7):1353–1357. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870401)59:7<1353::AID-CNCR2820590720>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira K, Liberman B, Rodrigues Pimentel-Filho F, Goldman J, Silva MER, Vieira JO, Buratini JA, Cukiert A. hCG-secreting pineal teratoma causing precocious puberty: report of two patients and review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;15(8):1195–1201. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2002.15.8.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivarola MA, Belgorosky A, Mendilaharzu H, Vidal G. Precocious puberty in children with tumours of the suprasellar and pineal areas: organic central precocious puberty. Acta Paediatrica. 2001;90(7):751–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer RJ, Sutton LN, Rosenstock JG. et al. Pineal region tumors of childhood. Pediatrics. 1984;74(1):97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puget S, Garnett M, Wray A, Grill J, Habrand JL, Bodaert N, Zerah M, Bezerra M, Renier D, Pierre-Kahn A, Sainte-Rose C. Pediatric craniopharyngiomas: classification and treatment according to the degree of hypothalamic involvement. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2007;106(1):3–12. doi: 10.3171/ped.2007.106.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett MR, Puget S, Grill J, Sainte-Rose C. Craniopharyngioma. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2007;2(1, article 18) doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty AR, Chrousos GP. Pituitary tumors in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;84(12):4317–4323. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.12.4317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunin GR, Surawicz TS, Witman PA, Preston-Martin S, Davis F, Bruner JM. The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1998;89(4):547–551. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.4.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunin GR, Surawicz TS, Witman PA, Preston-Martin S, Davis F, Bruner JM. The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1998;89(4):547–551. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.4.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt R, Magnani C, Pavenello M, Caruso S, Dama E, Garrè ML. Epidemiological aspects of craniopharyngioma. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;19(1):289–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries L, Weintrob N, Phillip M. Craniopharyngioma presenting as precocious puberty and accelerated growth. Clinical Pediatrics. 2003;42(2):181–184. doi: 10.1177/000992280304200213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YD, Shu SG, Chi CS, Hsieh PP, Ho WL. Precocious puberty associated with growth hormone deficiency in a patient with craniopharyngioma: report of one case. Acta Paediatrica Taiwanica. 2001;42(4):243–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rocco C, Caldarelli M, Tamburrini G, Massimi L. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas—experience with a pediatric series. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;19(1, supplement):355–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita T, Bowman RM. Craniopharyngiomas in children: surgical experience at Children's Memorial Hospital. Child's Nervous System. 2005;21(8-9):729–746. doi: 10.1007/s00381-005-1202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Tamburrini G, Cappa M, Di Rocco C. Long-term results of the surgical treatment of craniopharyngioma: the experience at the Policlinico Gemelli, Catholic University, Rome. Child's Nervous System. 2005;21(8-9):747–757. doi: 10.1007/s00381-005-1186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott RE, Moshel YA, Wisoff JH. Surgical treatment of ectopic recurrence of craniopharyngioma: report of 4 cases. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2009;4(2):105–112. doi: 10.3171/2009.3.PEDS0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamida Y, Mikami T, Hashi K, Houkin K. Surgical management of the recurrence and regrowth of craniopharyngiomas. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2005;103(2):224–232. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.2.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober WB. Selected items from the history of pathology: Eugen Albrecht, MD (1872–1908): hamartoma and choristoma. American Journal of Pathology. 1978;91(3):606. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdueza JM, Cristante L, Dammann O, Bentele K, Vortmeyer A, Saeger W, Padberg B, Freitag J, Herrmann HD, Hoffman HJ, Fahlbusch R. Hypothalamic hamartomas: with special reference to gelastic epilepsy and surgery. Neurosurgery. 1994;34(6):949–958. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199406000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arita K, Ikawa F, Kurisu K, Sumida M, Harada K, Uozumi T, Monden S, Yoshida J, Nishi Y. The relationship between magnetic resonance imaging findings and clinical manifestations of hypothalamic hamartoma. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1999;91(2):212–220. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.2.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousso IH, Kourti M, Papandreou D, Tragiannidis A, Athanasiadou F. Central precocious puberty due to hypothalamic hamartoma in a 7-month-old infant girl. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;167(5):583–585. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0515-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Carmel P, Schwartz MS, Witkin JW, Bentele KHP, Westphal M, Piatt JH, Costa ME, Cornea A, Ma YJ, Ojeda SR. Some hypothalamic hamartomas contain transforming growth factor α, a puberty-inducing growth factor, but not luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;84(12):4695–4701. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.12.4695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Ojeda SR. Pathogenesis of precocious puberty in hypothalamic hamartoma. Hormone Research. 2002;57(2, supplement):31–34. doi: 10.1159/000058097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Parent AS, Ojeda SR. Hypothalamic hamartoma: a paradigm/model for studying the onset of puberty. Endocrine Development. 2005;8:81–93. doi: 10.1159/000084095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassio A, Cacciari E, Zucchini S, Balsamo A, Diegoli M, Orsini F. Central precocious puberty: clinical and imaging aspects. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;13(1, supplement):703–708. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2000.13.s1.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochman HI, Judge DM, Reichlin S. Precocious puberty ahd hypothalamic hamartoma. Pediatrics. 1981;67(2):236–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Probst EN, Hauffa BP, Partsch CJ, Dammann O. Association of Morphological Characteristics with Precocious Puberty and/ or Gelastic Seizures in Hypothalamic Hamartoma. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88(10):4590–4595. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-022018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyko OB, Curnes JT, Oakes WJ, Burger PC. Hamartomas of the tuber cinereum: CT, MR, and pathologic findings. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 1991;12(2):309–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debeneix C, Bourgeois M, Trivin C, Sainte-Rose C, Brauner R. Hypothalamic hamartoma: comparison of clinical presentation and magnetic resonance images. Hormone Research. 2001;56(1-2):12–18. doi: 10.1159/000048084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau EA, Liow K, Frattali CM, Wiggs E, Turner JT, Feuillan P, Sato S, Patsalides A, Patronas N, Biesecker LG, Theodore WH. Hypothalamic hamartomas and seizures: distinct natural history of isolated and pallister-hall syndrome cases. Epilepsia. 2005;46(1):42–47. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.68303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesecker LG, Abbott M, Allen J, Clericuzio C, Feuillan P, Graham JM, Hall J, Kang S, Olney AH, Lefton D, Neri G, Peters K, Verloes A. Report from the workshop on Pallister-Hall syndrome and related phenotypes. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1996;65(1):76–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19961002)65:1<76::AID-AJMG12>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesecker LG, Graham JM. Pallister-Hall syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics. 1996;33(7):585–589. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.7.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RH, Freeman JL, Shouri MR, Izzillo PA, Rosenfeld JV, Mulley JC, Harvey AS, Berkovic SF. Somatic mutations in GLi3 can cause hypothalamic hamartoma and gelastic seizures. Neurology. 2008;70(8):653–655. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000284607.12906.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent AS, Matagne V, Westphal M, Heger S, Ojeda S, Jung H. Gene expression profiling of hypothalamic hamartomas: a search for genes associated with central precocious puberty. Hormone Research. 2008;69(2):114–123. doi: 10.1159/000111815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahachoklertwattana P, Kaplan SL, Grumbach MM. The luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-secreting hypothalamic hamartoma is a congenital malformation: natural history. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1993;77(1):118–124. doi: 10.1210/jc.77.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Téllez-Zenteno JF, Serrano-Almeida C, Moien-Afshari F. Gelastic seizures associated with hypothalamic hamartomas. An update in the clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2008;4(6):1021–1031. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohn A, Schoof E, Fahlbusch R, Wenzel D, Dörr HG. The endocrine spectrum of arachnoid cysts in childhood. Pediatric Neurosurgery. 1999;31(6):316–321. doi: 10.1159/000028882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatli M, Guzel A. Bilateral temporal arachnoid cysts associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. Journal of Child Neurology. 2007;22(6):775–779. doi: 10.1177/0883073807304014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth TN, Timmons C, Shapiro K, Rollins NK. Pre- and postnatal MR imaging of hypothalamic hamartomas associated with arachnoid cysts. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2004;25(7):1283–1285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HP, Tung YIC, Tsai WY, Kuo MF, Peng SF. Arachnoid cyst with GnRH-dependent sexual precocity and growth hormone deficiency. Pediatric Neurology. 2004;30(2):143–145. doi: 10.1016/S0887-8994(03)00418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starzyk J, Kwiatkowksi S, Urbanowicz W, Starzyk B, Harasiewicz M, Kalicka-Kasperczyk A, Tylek-Lemańska D, Dziatkowiak H. Suprasellar arachnoidal cyst as a cause of precocious puberty—report of three patients and literature overview. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;16(3):447–455. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2003.16.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Gupta VK, Khosla VK, Dash RJ, Bhansali A, Kak VK, Vasishta RK. Suprasellar arachnoid cyst presenting with precocious puberty - Report of two cases. Neurology India. 1999;47(2):148–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgut M, Ozcan OE. Suprasellar arachnoid cyst as a cause of precocious puberty and bobble-head doll phenomenon [1] European Journal of Pediatrics. 1992;151(1):76. doi: 10.1007/BF02073900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Singhal N. Suprasellar arachnoid cyst with delayed puberty. Indian Pediatrics. 2007;44(11):858–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasar M, Bozlar U, Yetiser S, Bolu E, Tasar A, Gonul E. Idiopathic hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism associated with arachnoid cyst of the middle fossa and forebrain anomalies: presentation of an unusual case. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2005;28(10):935–939. doi: 10.1007/BF03345326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzel A, Trippel M, Ostertage CB. Suprasellar arachnoid cyst: a 20-year follow-up after stereotactic internal drainage: case report and review of the literature. Turkish Neurosurgery. 2007;17(3):211–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar CA, Conte FA, Kaplan SL, Grumbach MM. Human chorionic gonadotropin-secreting pineal tumor: relation to pathogenesis and sex limitation of sexual precocity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1981;53(3):656–660. doi: 10.1210/jcem-53-3-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Marcaigh AS, Ledger GA, Roche PC, Parisi JE, Zimmerman D. Aromatase expression in human germinomas with possible biological effects. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1995;80(12):3763–3766. doi: 10.1210/jc.80.12.3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitanaka C, Matsutani M, Sora S, Kitanaka S, Tanae A, Hibi I. Precocious puberty in a girl with an hCG-secreting suprasellar immature teratoma. Case report. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1994;81(4):601–604. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.4.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Völkl TMK, Langer T, Aigner T, Greess H, Beck JD, Rauch AM, Dörr HG. Klinefelter syndrome and mediastinal germ cell tumors. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2006;140(5):471–481. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden SA, Germak JA. Klinefelter syndrome presenting with precocious puberty due to a human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG)-producing mediastinal germinoma. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;19(11):1371. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2006.19.11.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littley MD, Shalet SM, Beardwell CG, Ahmed SR, Applegate G, Sutton ML. Hypopituitarism following external radiotherapy for pituitary tumours in adults. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 1989;70(262):145–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson HK, Shalet SM. The impact of cancer therapy on the endocrine system in survivors of childhood brain tumours. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2004;11(4):589–602. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J. Disturbance of pubertal development after cancer treatment. Best Practice and Research. 2002;16(1):91–103. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvy-Stuart AL, Clayton PE, Shalet SM. Cranial irradiation and early puberty. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1994;78(6):1282–1286. doi: 10.1210/jc.78.6.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberfield SE, Soranno D, Nirenberg A, Heller G, Allen JC, David R, Levine LS, Sklar CA. Age at onset of puberty following high-dose central nervous system radiation therapy. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150(6):589–592. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170310023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannering B, Jansson C, Rosberg S, Albertsson-Wikland K. Increased LH and FSH secretion after cranial irradiation in boys. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 1997;29(4):280–287. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199710)29:4<280::AID-MPO8>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toogood AA. Endocrine consequences of brain irradiation. Growth Hormone and IGF Research. 2004;14(supplement):S118–S124. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner R, Czernichow P, Rappaport R. Precocious puberty after hypothalamic and pituitary irradiation in young children. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1984;311(14):920. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198410043111414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constine LS, Woolf PD, Cann D, Mick G, McCormick K, Raubertas RF, Rubin P. Hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction after radiation for brain tumors. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;328(2):87–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301143280203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GT, Whitton JA, Gajjar A, Kun LE, Chow EJ, Stovall M, Leisenring W, Robison LL, Sklar CA. Abnormal timing of Menarche in survivors of central nervous system tumors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2562–2570. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow EJ, Friedman DL, Yasui Y, Whitton JA, Stovall M, Robison LL, Sklar CA. Timing of menarche among survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2008;50(4):854–858. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkebaek NH, Fisker S, Clausen N, Tuovinen V, Sindet-Pedersen S, Christiansen JS. Growth and endocrinological disorders up to 21 years after treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 1998;30(6):351–356. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199806)30:6<351::AID-MPO9>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubberfield TG, Byrne GC, Jones TW. Growth and growth hormone secretion after treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood: 18-Gy versus 24-Gy cranial irradiation. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 1995;17(2):167–171. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199505000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley C, Cowell C, Jimenez M, Burger H, Kirk J, Bergin M, Stevens M, Simpson J, Silink M. Normal or early development of puberty despite gonadal damage in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;321(3):143–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907203210303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GT, Chow EJ, Sklar CA. Alterations in pubertal timing following therapy for childhood malignancies. Endocrine Development. 2009;15:25–39. doi: 10.1159/000207616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carel J-C, Eugster EA, Rogol A. et al. Consensus statement on the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e752–e762. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stava CJ, Jimenez C, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R. Endocrine sequelae of cancer and cancer treatments. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2007;1(4):261–274. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney JG, Ness KK, Stovall M, Wolden S, Punyko JA, Neglia JP, Mertens AC, Packer RJ, Robison LL, Sklar CA. Final height and body mass index among adult survivors of childhood brain cancer: childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88(10):4731–4739. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T. Sufficiently long-term treatment with combined growth hormone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog can improve adult height in short children with isolated Growth Hormone Deficiency (GHD) and in non-GHD short children. Pediatric Endocrinology Reviews. 2007;5(1):471–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn B, Julius JR, Blethen SL. Combined use of growth hormone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues: the National Cooperative Growth Study experience. Pediatrics. 1999;104(4):1014–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cara JF, Kreiter ML, Rosenfield RL. Height prognosis of children with true precocious puberty and growth hormone deficiency: effect of combination therapy with gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist and growth hormone. Journal of Pediatrics. 1992;120(5):709–715. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80232-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner SE, Huang GJM, McMahon D, Sklar CA, Oberfield SE. Growth hormone therapy in children after cranial/craniospinal radiation therapy: sexually dimorphic outcomes. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;89(12):6100–6104. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauras N, De Pijem LG, Hsiang HY, Desrosiers P, Rapaport R, Schwartz ID, Klein KO, Singh RJ, Miyamoto A, Bishop K. Anastrozole increases predicted adult height of short adolescent males treated with growth hormone: a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial for one to three years. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;93(3):823–831. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiani D, Damiani D. Pharmacological management of children with short stature: the role of aromatase inhibitors. Jornal de Pediatria. 2007;83(5, supplement):S172–S177. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faglia G, Arosio M, Porretti S. Delayed closure of epiphyseal cartilages induced by the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole. Would it help short children grow up? Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2000;23(11):721–723. doi: 10.1007/BF03345059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]