Abstract

O6-methyl-2'-deoxyguanosine (O6-Me-dG) is a potent mutagenic DNA adduct that can be induced by a variety of methylating agents, including tobacco-specific nitrosamine, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK). O6-Me-dG is directly repaired by the specialized DNA repair protein, O6-alkylguanine-DNA-alkyltransferase (AGT), which transfers the O6-alkyl group from the modified guanine to a cysteine thiol within the active site of the protein. Previous investigations suggested that AGT repair of O6-alkylguanines may be sequence-dependent as a result of flanking nucleobase effects on DNA conformation and energetics. In the present work, a novel high performance/pressure liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS) based approach was developed to analyze the kinetics of AGT-mediated repair of O6-Me-dG adducts placed at different sites within the double stranded DNA sequence representing codons 8–17 of the K-ras protooncogene, 5'-G1TA G2TT G3G4A G5CT G6G7T G8G9C G10TA G11G12C AAG13 AG14T-3', where G5, G6, G7, G8, G9, G10, or G11 was replaced with O6-Me-dG. The second guanine of K-ras codon 12 (G7 in our numbering system) is a major mutational hotspot for G A transitions observed in lung tumors of smokers and in neoplasms induced in laboratory animals by exposure to methylating agents. O6-Me-dG-containing duplexes were incubated with human recombinant AGT protein, and the reactions were quenched at specific times. Following acid hydrolysis to release purines, isotope dilution HPLC-ESI-MS/MS was used to determine the amounts of O6-Me-G remaining in DNA. The relative extent of demethylation for O6-Me-dG adducts located at G5, G6, G7, G8, G9, G10, or G11 following 10 second incubation with AGT showed little variation as a function of sequence position. Furthermore, the second order rate constants for the repair of O6-Me-dG adducts located at the first and second positions of the K-ras codon 12 (5'-G6G7T-3') were similar (1.4 × 107 M−1s−1 vs. 7.4 × 106 M−1s−1 respectively), suggesting that O6-Me-dG repair by AGT is not the determining factor for K-ras codon 12 mutagenesis following exposure to methylating agents. The new HPLC-ESI-MS/MS assay developed in this work is a valuable tool which will be used to further explore the role of local sequence environment and endogenous DNA modifications in shaping mutational spectra of NNK and other methylating agents.

Introduction

A large fraction (24–56%) of human primary adenocarcinomas contain genetic changes within codon 12 of the K-ras proto-oncogene (1–7). These mutations include both G→T transversions (GGT→TGT, GTT) and G→A transitions (GGT→GAT), which have been shown to activate the K-ras proto-oncogene, leading to an uncontrolled cell growth and a loss of cell differentiation (1–3,6). K-ras codon 12 mutations are much more prevalent in smokers than in non-smokers (4), suggesting a role for tobacco smoke components in the induction of these mutations. Furthermore, the same characteristic G→A transitions within K-ras codon 12 (GGT→GAT) are observed in mouse lung tumors induced by the potent tobacco carcinogen, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) (8), making it a likely causative agent for these genetic changes.

NNK is a tobacco specific N-nitrosamine which has been shown to specifically induce lung tumors in laboratory animals, independent of the route of administration (9,10). Metabolic activation of NNK yields methyl- and pyridyloxobutyl-diazonium ions that react with DNA to give highly mutagenic O6-methyl-2'-deoxyguanosine (O6-Me-dG) and O6-[4-oxo-(3-pyridyl)but-1-yl]-2'-deoxyguanosine (O6-POB-dG) lesions (11–13). O6-Me-dG, although a minor lesion (6% of total methylation), is critical for NNK mutagenesis based on its strong mispairing characteristics (14) and its key role in the induction of lung tumors in NNK-treated mice (13).

Both O6-Me-dG and O6-POB-dG adducts are substrates for the specialized repair protein, O6-alkylguanine-DNA-alkyltransferase (AGT). AGT transfers the O6-alkyl group from the damaged base to a cysteine residue within the active site of the protein (Cys-145 for human AGT), restoring unsubstituted guanine (15,16). AGT acts preferentially on double stranded DNA and does not require any co-factors. To allow access to the cysteine acceptor site, the O6-alkyl-2'-deoxyguanosine (O6-Alk-dG) is flipped out of the DNA helix into the binding pocket of AGT, while another amino acid (Arg-128 in the human enzyme) takes its place in the double helix (17). Two other conserved residues, His-148 and Glu-172 of human AGT, are involved in generating a thiolate ion at Cys-145, which then acts as a nucleophile, displacing the alkyl group in O6-Alk-dG and regenerating a normal guanine (18). The alkylated protein is inactive and is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin/proteasomal system (19).

One possible explanation for the predominance of G→A mutations at the second G of K-ras codon 12 is the inefficient AGT repair of O6-Me-dG lesions formed at this position. Several previous studies reported that DNA sequence context can affect the rates of AGT mediated repair of O6-Alk-dG (20,21,21–23). In some cases, O6-Alk-dG preceded by guanine was repaired slower than those flanked by cytosine nucleobases (20,21,24), while others observed little sequence specificity (22) or detected opposite reactivity order for AGT-mediated demethylation (G[O6-Alk-dG]N > C [O6-Alk-dG]N (25). The goal of the present work was to determine the rates of AGT-mediated repair of O6-Alk-dG lesions located within K-ras codon 12 and surrounding DNA sequence by a novel approach based on high performance/pressure liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS) analyses of O6-Me-G lesions. Our results reveal that local sequence context has only moderate effect on AGT repair rates of O6-Me-dG within K-ras gene derived duplexes, suggesting that other factors, e.g. preferential adduct formation, mispairing, or mutant selection for growth, may be responsible for the observed mutational specificity.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Human recombinant AGT with a C-terminal (His)6 tail (observed MW = 21,880 (ESI+ MS), calculated Mr = 21,876) was prepared as reported previously (26). The protein was aliquoted and stored in 0.1 mg/ml Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (KLH) solution at − 80 °C. The concentration of active AGT was determined for each set of experiments by incubating with known amounts of O6-Me-dG containing DNA, followed by HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of O6-Me-G to determine the extent of demethylation as described below. Bovine serum albumin (BSA), ammonium acetate (99.999% pure), 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) and deuterated methanol were procured from Aldrich Chemical Company (Milwaukee, WI). D,L-Dithiothreitol (DTT), trace analysis grade acetic acid, and O6-Me-G were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). 5'-dimethoxytrityl-N-isobutyryl-O6-methyl-2'-deoxyguanosine, 3'-[(2-cyanoethyl)-(N,N-diisopropyl)]-phosphoramidite (O6-Me-dG-CE phosphoramidite) was obtained from Glen Research Corp. (Sterling, VA). Tris-HCl was bought from EM Science (Cincinnati, OH). Magnesium chloride was purchased from ICN Biochemicals, Inc. (Aurora, OH). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was obtained from Avocado Research Chemicals Limited (Heysham, Lancashire). Ammonium hydroxide and ammonium acetate (99.9% pure) were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Hydrochloric acid was from Mallinckrodt Chemicals (Philipsburg, NJ). All HPLC and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) grade solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Centricon YM-10 filters (0.5 mL) were procured from Phenomenex Corp. (Torrance, CA).

Preparation of O6-Me-G containing DNA oligodeoxynucleotides

DNA oligomers containing O6-Me-dG at specified locations (Table 1) were prepared by standard methods on a DNA synthesizer using O6-Me-dG-CE phosphoramidite obtained from Glen Research Corp. (Sterling, VA). DNA sequences (Table 1) were derived from a region of the K-ras gene containing known lung cancer mutational “hotspot” at codon 12 (5'-GGT-3'→ GAT). In all double stranded DNA substrates, cytosine was introduced opposite O6-Me-dG. Synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides were deprotected in the presence of 10% DBU/anhydrous methanol (room temperature, 5 days in the dark) and purified by reverse-phase HPLC as described elsewhere (27,28). HPLC fractions corresponding to the full-length oligomers were collected and concentrated under vacuum. The identity and purity of each strand were established by HPLC with UV detection and by capillary HPLC-ESI− MS (Table 1). The DNA oligodeoxynucleotide strands were considered sufficiently pure for our study if the impurity peaks in the UV trace at 260 nm constituted less than 2% of the total area. DNA concentrations were established by 2'-deoxyguanosine quanitation in enzymatic digests as described previously (28). To obtain double stranded DNA substrates for repair studies, equimolar amounts of the complementary strands were combined in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris pH 8 and 50 mM sodium chloride, followed by heating to 76 °C and slowly cooling to room temperature. Duplex formation was complete as demonstrated by non-denaturing HPLC.

Table 1.

DNA oligodeoxynuclotides employed in the present study.

| Oligonucleotide ID | Sequence | M.W.

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| calculated | observed | ||

| (+) p53 Exon5 Codon158, O6-Me-G | ACC CGC GTC C[O6-Me-G]C GCC ATG GCC | 6343 | 6343 |

| (−) p53 Exon5 Codon158 | GGC CAT GGC GCG GAC GCG GGT | 6529 | 6529 |

| (+) K-ras | GTA GTT GGA GCT GGT GGC GTA GGC AAG AGT | 9423 | 9423 |

| (+) O6-Me-G5 K-ras | GTA GTT GGA [O6-Me-G]CT GGT GGC GTA GGC AAG AGT | 9437 | 9438 |

| (+) O6-Me-G6 K-ras | GTA GTT GGA GCT [O6-Me-G]GT GGC GTA GGC AAG AGT | 9437 | 9438 |

| (+) O6-Me-G7 K-ras | GTA GTT GGA GCT G[O6-Me-G]T GGC GTA GGC AAG AGT | 9437 | 9438 |

| (+) O6-Me-G8 K-ras | GTA GTT GGA GCT GGT [O6-Me-G]GC GTA GGC AAG AGT | 9437 | 9438 |

| (+) O6-Me-G9 K-ras | GTA GTT GGA GCT GGT G[O6-Me-G]C GTA GGC AAG AGT | 9437 | 9438 |

| (+) O6-Me-G10 K-ras | GTA GTT GGA GCT GGT GGC [O6-Me-G]TA GGC AAG AGT | 9437 | 9438 |

| (+) O6-Me-G11 K-ras | GTA GTT GGA GCT GGT GGC GTA [O6-Me-G]GC AAG AGT | 9437 | 9437 |

| (−) K-ras | ACT CTT GCC TAC GCC ACC AGC TCC AAC TAC | 8991 | 8993 |

Synthesis of O6-trideuteromethyl-guanine (O6- CD3-G)

O6-trideuteromethyl-2'-deoxyguanosine (O6-CD3-dG) was synthesized, purified, and structurally characterized as previously described (27). O6-trideuteromethyl-guanine (O6-CD3-G) was prepared by acid hydrolysis of O6-CD3-dG (0.1 N HCl, 70 °C for 1 hour). O6-CD3-G was purified by HPLC on a semi-preparatory Suplecosil-LC-18-DB HPLC column (10 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA) maintained at 25 °C and eluted at a 3 mL/minute flow rate. HPLC separation was carried out with 150 mM ammonium acetate (A) and acetonitrile (B). Solvent composition was changed linearly from 2 % to 15.5 % B over a period of 18 minutes and then held constant at 15.5 % over the next 12 minutes. The eluent was monitored by UV absorbance at 260 nm. Under these conditions, O6-CD3-G eluted at 18 minutes.

The identity of synthetic O6-CD3-G was confirmed by comparison of its HPLC retention time, UV spectrum, and MS/MS fragmentation with commercial unlabeled O6-Me-G. O6-CD3-G stock solution concentrations were determined by HPLC-UV analysis using a standard curve constructed by injecting known amounts of O6-Me-G and confirmed by HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS of O6-Me-G/O6-CD3-G mixtures containing known amounts of the unlabeled compound. HPLC-UV analysis was carried out with a Supelcosil LC-18-DB column (2.1 × 250 mm, 5 μm, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA) maintained at 25 °C and eluted at 0.2 mL/min. Isotopic purity of O6-CD3-G standard (> 99.98%) was verified by ESI+-MS and MS/MS. HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS was carried out as described below.

HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analyses of O6-Me-G

All HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analyses were performed with an Agilent 1100 Capillary HPLC system interfaced to a Finnigan Quantum Ultra triple quadrupole (TSQ) mass spectrometer. Capillary HPLC separations were performed on a Zorbax SB-C18 column (150 × 0.5 mm, 5 μm, Agilent Technologies) eluted isocratically with 6% acetonitrile in 15 mM ammonium acetate, pH 5.5. The column was maintained at 25 °C and eluted at a 15 μL/min flow rate. At these conditions, O6-Me-G and O6-CD3-G eluted at 6.8–6.9 minutes. The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive ion mode with a sheath gas pressure of 20 and nitrogen as the nebulizing and drying gas. Electrospray ionization was achieved at a spray voltage of 3.0 kV, and the temperature of the heated capillary was 250 °C. MS/MS fragmentation was achieved with a source collision induced dissociation (CID) of 14 V, a collision energy of 25 V, and a collision pressure of 1.2 mTorr. The instrument was tuned to maximum sensitivity by directly infusing O6-Me-G standard solution. HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of standard mixtures containing O6-Me-G and O6-CD3-G at a known molar ratio ensured that the compounds could be resolved and accurately quantified by our methods. Selected reaction monitoring (SRM) using the MS/MS transitions corresponding to the neutral loss of NH3 from O6-Me-G (m/z = 166.1 → 149.0) and O6-CD3-G (m/z = 169.1 → 152.0) was used for quantitative analyses. HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS limit of detection for O6-Me-G was estimated as 50 fmol (S/N = 3).

HPLC-ESI-MS/MS method validation

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS method accuracy and precision were validated with an analyte recovery assay as follows. Unmethylated duplexes (5'-G1TA G2TT G3G4A G5CT G6G7T G8G9C G10TA G11G12C AAG13 AG14T-3', + stand) (1 pmol aliquots, in triplicate) were combined with known amounts (0.05 – 1 pmol) of the corresponding synthetic duplex in which G10 was replaced with O6-Me-G. DNA mixtures were dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8 buffer containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mg/mL BSA and 0.5 mM DTT. Hydrochloric acid (1N) was added to the DNA solution to achieve a concentration of 0.1 N, followed by the addition of AGT (250 fmol) and mild acid hydrolysis to release O6-Me-G from the DNA backbone. The solution was cooled and neutralized with ammonium hydroxide. Following the addition of O6-CD3-G internal standard (236 fmol), DNA hydrolysates were filtered through YM-10 centricon filters, dried, and re-suspended in 15 μL of 15 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.5. The amount of O6-Me-G was determined by HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS using isotope dilution with O6-CD3-G.

Assay of O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase Activity

Double stranded oligodeoxynucleotides bearing a single O6-Me-G residue (5'-ACC CGC GTC C[O6-Me-G]C GCC ATG GCC-3' + complement, in duplicate, 2 pmol each) were dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8 buffer containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mg/mL BSA and 0.5 mM DTT (175 μl). Human recombinant AGT protein was added to achieve AGT/O6-Me-G molar ratios of 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 (total protein), followed by incubation for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of HCl to reach a concentration of 0.1 N HCl. Samples were then subjected to mild acid hydrolysis (70 °C for 1 hour) to release O6-Me-G, cooled, and neutralized with ammonium hydroxide. Following the addition of O6-CD3-G internal standard (236 fmol), the solutions were filtered through YM-10 centricons, dried, and re-suspended in 15 μL of 15 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.5. The amount of O6-Me-G was determined by capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS as described above. Between 35 and 45% of total protein was active, depending on an aliquot.

AGT reactions with O6-Me-G containing DNA duplexes

Extent of Repair (Single Time Point) Experiments

All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated 2 or 3 times (total N = 6 or 9). Double stranded oligomers containing a single O6-Me-dG residue at a specifice site (1 pmol each) were dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8 buffer containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, and 0.5 mM DTT. Human recombinant AGT protein (stored in 3 μL aliquots of 10 μg/μL at -80 °C) was diluted with the same buffer to achieve a concentration of 1.37 μM total AGT and kept on ice at all times. An aliquot of the AGT solution containing 600 fmol of the active protein was added to DNA, followed by incubation for 10 seconds. The reactions were terminated by the addition of HCl to achieve the concentration of 0.1 N HCl. Samples were subjected to mild acid hydrolysis (70 °C for 1 hour) to release O6-Me-G, cooled, and neutralized with ammonium hydroxide. Following the addition of O6-CD3-G internal standard (236 fmol), the solutions were filtered through YM-10 microfilters to remove protein. The filtrates were dried under reduced pressure and re-suspended in 15 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.5 (15 μL). O6-Me-G amounts remaining in DNA were determined by HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS as described above.

Kinetics of Repair (Time Course) Experiments

These experiments were performed in triplicate. Double stranded oligomers containing a single O6-Me-G (O6-Me-G6 K-ras or O6-Me-G7 K-ras, Table 1, 500 fmol each) were dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8 buffer containing 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, and 0.5 mM DTT. Human recombinant AGT protein was diluted with the same buffer to achieve a concentration of 1.37 μM total AGT. AGT solution corresponding to 428 fmol of the active protein was added to initiate demethylation. The reactions were terminated at different time points (3–300 sec) by the addition of HCl to achieve a concentration of 0.1 N HCl. Samples were subjected to mild acid hydrolysis (70 °C for 1 hour) to release O6-Me-G, cooled, and neutralized with ammonium hydroxide. Following the addition of O6-CD3-G internal standard (236 fmol), the solutions were filtered through YM-10 filters to remove protein. The filtrates were dried under reduced pressure and re-suspended in 15 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.5 (15 μL). The amounts of O6-Me-G remaining in DNA were determined by HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS as described above.

Experiments that involved varying AGT concentrations were performed as described above using double stranded oligomers containing a single O6-Me-G at position G6 (O6-Me-G6 K-ras, Table 1). AGT amounts were varied between 50 and 856 fmol.

Statistical Analysis of the Data

All statistical analyses were carried out by Yan Zhang, Zhong-ze Li, and Joseph Koopmeiners at the University of Minnesota Biostatistics Core. Three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the extent of O6-Me-G repair at different positions within K-ras derived sequence. Tukey’s method was used for multiple pairwise comparisons of the extent of repair at different sites. Two-way analysis of variance was used to compare the repair time-course curves for O6-Me-G located at positions G6 and G7.

Results and Discussion

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS Approach to analyze the kinetics of O6-Me-G repair by AGT

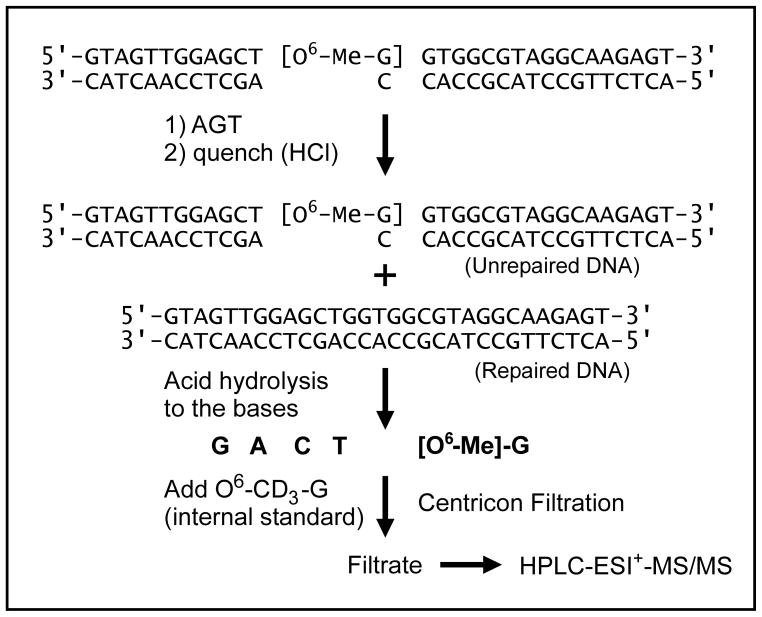

This investigation utilized a new quantitative HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS approach developed in our laboratory to analyze the kinetics of O6-Me-G repair by AGT as a function of local DNA sequence context (Figure 1). A series of synthetic 30-mer oligodeoxynucleotide duplexes were prepared representing K-ras codon 12 and surrounding sequence (5'-G1TA G2TT G3G4A G5CT G6G7T G8G9C GTA G10G11C AAG AG12T-3', + complement, G6G7T = codon 12). In each duplex, one of the guanine nucleobases in the (+) strand was replaced with O6-Me-G (Table 1).

Figure 1.

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS strategy used to analyze O6-Me-G repair by AGT.

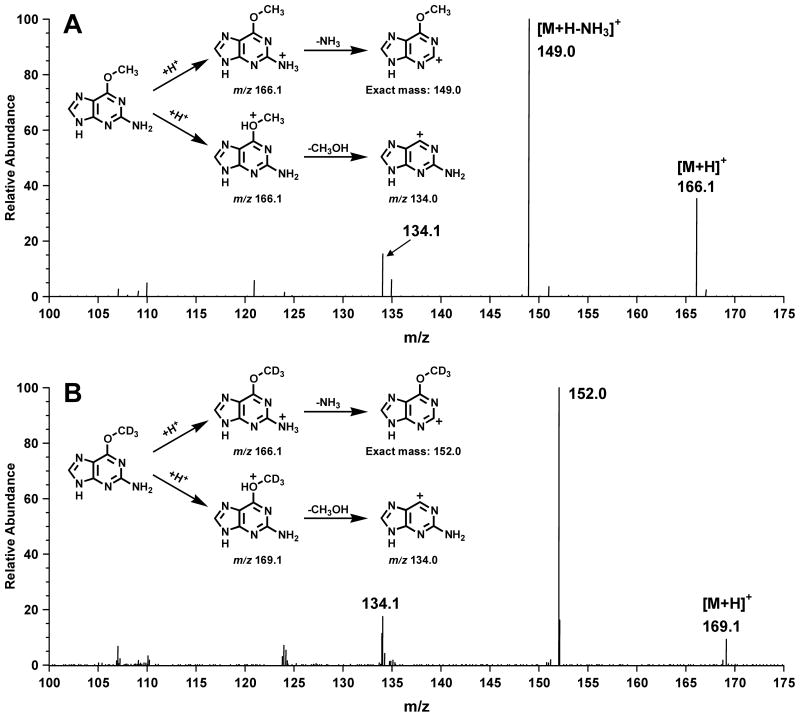

Following incubation of O6-Me-G-containing DNA with AGT for specific periods of time, HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of O6-Me-G released by mild acid hydrolysis was employed to determine the extent of repair (Figure 1). Quantitative analyses of O6-Me-G were performed via isotope dilution with O6-CD3-G internal standard. ESI+-MS/MS spectrum of O6-Me-G (m/z 166.1, (M+H)+, Figure 2A) contains a major product peak at m/z 149.0, while the ESI+-MS/MS product scan of O6-CD3-G (m/z 169.1, (M+H)+) results in a major fragment at m/z 152.0 (Figure 2B). This fragmentation corresponds to the neutral loss of the ammonia (17 D) from the exocyclic amino group of protonated O6-Me-G and O6-CD3-G molecules (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

ESI+-MS/MS spectra of O6-Me-G (A) and O6-CD3-G (B) and proposed structures of the major mass fragments.

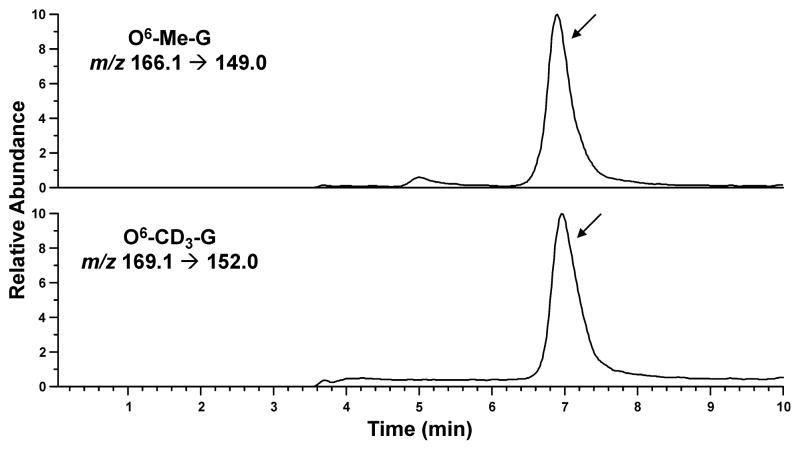

In order to achieve sensitive detection of O6-Me-G in DNA hydrolysates, triple quadrupole mass spectrometer was operated in the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode by following the transitions m/z 166.1 → 149.0 and m/z 169.1 → 152.0 for O6-Me-G and O6-CD3-G, respectively. At our conditions (Zorbax-SB-C18 eluted isocratically with 6% acetonitrile in 15 mM ammonium acetate, pH 5.5), both O6-Me-G and O6-CD3-G eluted at 6.8–6.9 min (Figure 3). HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS limit of detection for O6-Me-G was established as 50 fmol (S/N = 3).

Figure 3.

Capillary HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of O6-Me-G remaining in the synthetic DNA duplex (5'-GTA GTT GGA GCT [O6-Me-G]GT GGC GTA GGC AAG AGT-3', + complement) following incubation with the AGT repair protein. Double stranded DNA oligomer (1 pmol) was incubated with 600 fmol AGT for 10 seconds, followed by acid hydrolysis, addition of O6-CD3-G internal standard, and HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis as shown in Figure 1. The mass spectrometer was operated in the selected reaction monitoring mode by following the transitions m/z 169.1 → 152.0 and m/z 166.1 → 149.0 for O6-CD3-G and O6-Me-G , respectively.

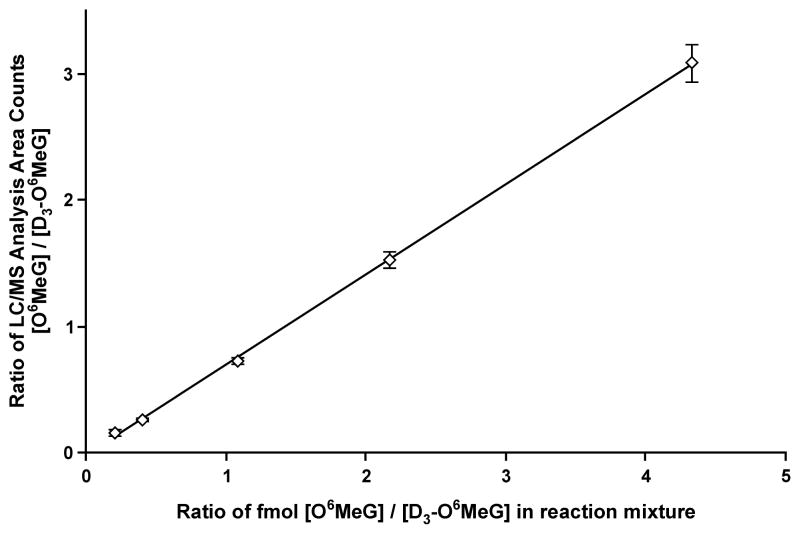

The quantitative HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS method was validated by the analyte recovery assay. Synthetic duplex (5'-GTA GTT GGA GCT GGT GGC GTA GGC AAG AGT-3' + complement) and the corresponding duplex containing a single O6-Me-G (5'-GTA GTT GGA GCT GGT GGC [O6-Me-G] TA GGC AAG AGT-3' + complement) were mixed at a known molar ratio in the presence of inactivated AGT. While unmethylated duplex amounts were kept at 1 pmol, O6-Me-G-containing DNA amounts were varied between 0.05 and 1 pmol to mimic the molar ratios observed at different time points during AGT repair reaction. DNA mixtures were hydrolyzed and processed according to the same method used for AGT repair mixtures (Figure 1). The accuracy and precision of the method was determined by plotting the ratio of observed to the ratio of expected values of the O6-Me-G/O6-CD3-G (Figure 4). The results of the validation experiments demonstrated that the isotope dilution HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS methodology was a sensitive and specific technique for O6-Me-G analysis in double stranded DNA. Since isotope HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS is considered the most accurate and reproducible detection method for carcinogen-DNA adducts (29), quantitative data obtained by this methodology are expected to be highly reliable.

Figure 4.

HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS method validation for O6-Me-G using isotope dilution with O6-CD3-G. Known amounts of synthetic DNA duplex containing a single O6-Me-G residue (5'-GTA GTT GGA GCT GGT GGC [O6-Me-G] TA GGC AAG AGT-3') (0.050 to 1 pmol) were mixed with 1 pmol of the corresponding unmethylated duplex and 250 fmol of denatured AGT protein, followed by mild acid hydrolysis, addition of O6-CD3-G internal standard, and HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis. O6-Me-G was quantitated from the HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS peak areas of O6-Me-G and O6-CD3-G.

Extent of O6-Me-G repair within K-ras derived DNA sequences

Several earlier studies suggested that O6-Me-dG repair within H-ras codon 12 is nonuniform; O6-Me-dG adducts located at the first guanine have been found to be repaired more efficiently than those on the second guanine ([O6-Me-G]GC > G[O6-Me-G]C) (20,21,24). However, AGT repair of O6-Me-G within K-ras codon 12 has not been previously examined. K-ras codon 12 is a major lung cancer mutational hot spot in smokers (GGT GAT) (1–7) and is also mutated in mouse lung tumors induced by exposure to NNK (8). We analyzed the extent of AGT-mediated repair of O6-Me-dG placed at seven different sites within a double stranded DNA 30-mer representing K-ras codon 12 and surrounding sequence (Table 1). Isotope dilution HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS methodology (Figure 1) was employed to quantify the O6-Me-G remaining in the DNA following a 10 second incubation with AGT protein. The extent of O6-Me-G repair at a time t (Et) was calculated as shown in equation 1, where A0 and At refer to O6-Me-G amounts present in DNA at time 0 (control) and t, respectively.

| (1) |

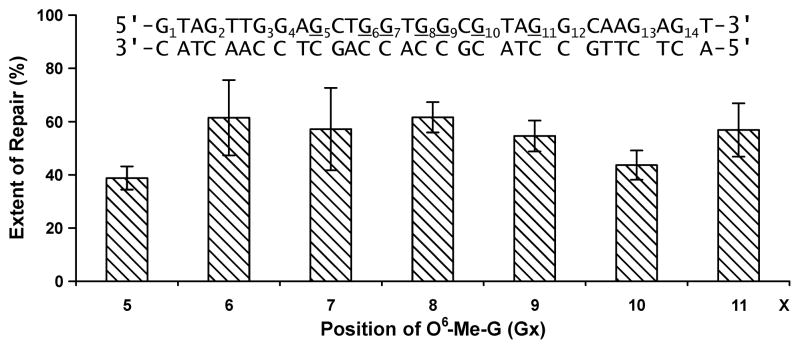

The extent of repair of O6-Me-G located at G5, G6, G7, G8, G9, G10 or G11 of the K-ras derived duplex (Table 1) following a 10 second incubation with 0.6 molar equivalents of recombinant AGT was between 40 and 60 %, depending on specific sequence position (Figure 5). The most efficient demethylation (62 %) was observed for O6-Me-dG adducts located at G6 and G8 (Figure 5). Repair results for these two positions (G6 and G8) were statistically the same (p > 0.98), probably because of their identical flanking nucleosides (G[O6-Me-G]T). O6-Me-G adducts located at the neighboring guanine bases (G7 and G9) were repaired slower (54–57 %, Figure 5), although these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.6). AGT repair efficiency was significantly lower at G5 (AGC, 38.8 %) and G10 (CGT, 43.7 %). This is unlikely a result of “end effects” on repair because G5 and G10 are 10 and 12 nucleotides away from the ends of the 30-mer duplex, respectively, and given the fact that G11 exhibited a greater repair efficiency (Figure 5). Although we did not calculate the second order rate constants for AGT-mediated demethylation of O6-Me-G located at each site within K-ras derived duplex, the results of these single time point experiments (Figure 5) were fully consistent with more complete kinetic analyses performed for O6-Me-G6 K-ras and O6-Me-G7 K-ras (see below).

Figure 5.

AGT repair of O6-Me-G located at different positions within synthetic DNA duplex derived from the K-ras gene (5'-G1TA G2TT G3G4A G5CT G6G7T G8G9C G10TA G11G12C AAG13 AG14T-3', + complement, Table 1). Synthetic DNA duplexes containing a single O6-Me-G base at G5, G6, G7, G8, G9, G10, or G11 (1 pmol) were incubated with human recombinant AGT (600 fmol) for 10 seconds, followed by acid hydrolysis, addition of O6-CD3-G internal standard and HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of O6-Me-G. The results were compiled from 3 different experiments (total N = 12).

Time Course for O6-Me-G repair within K-ras codon 12

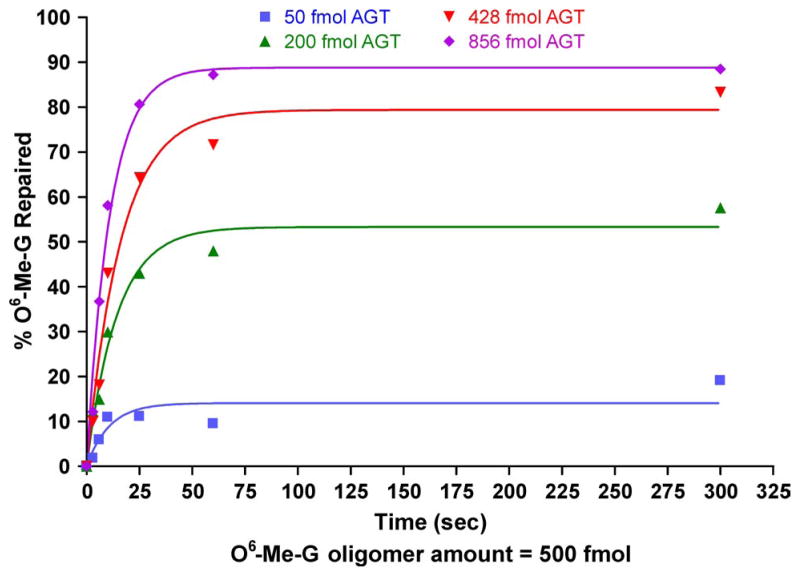

In order to analyze the kinetics of AGT repair of O6-Me-G within K-ras codon 12 in a greater detail, the extent of demethylation of the adducts located at G6 and G7 over time was investigated. AGT is known to react with its DNA substrate according to second-order kinetics, with reaction rates proportional to concentrations of AGT and O6-Me-G-containing DNA (30). As shown in Figure 6, AGT reacted with O6-Me-G6 K-ras duplex in a time-dependent manner, but achieved saturation following 75–100 sec incubation. The rates of reaction increased with increasing AGT amounts from 50 to 200, 428, and 856 fmol, gradually leveling off (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Time course of O6-Me-G repair within a DNA duplex derived from K-ras gene in the presence of different amounts of AGT. Synthetic DNA duplex 5'-GTA GTT GGA GCT [O6-Me-G] GT GGC GTA GGC AAG AGT-3', (+ complement, 500 fmol) was incubated with 50, 200, 428 or 856 fmol of human recombinant AGT protein, and the reactions were terminated at different time points by the addition of HCl. The samples were acid hydrolyzed to release purines, followed by the addition of O6-CD3-G internal standard and HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis of O6-Me-G.

Second order rate constants (k) for AGT repair of O6-Me-G6 and O6-Me-G7 K-ras duplexes were calculated from the equation , where A and B are the concentrations of AGT and O6-Me-G, respectively, and Ct is the amount of O6-Me-G repaired at time t. The subscripts ‘0’ and ‘t’ refer to the concentration of these species at time 0 and any a time t. The second order reaction rate constant in M−1 sec−1 was provided by slope of the kt versus t plot as defined in equation 3, 4 and 5 respectively (See Supplement 1).

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

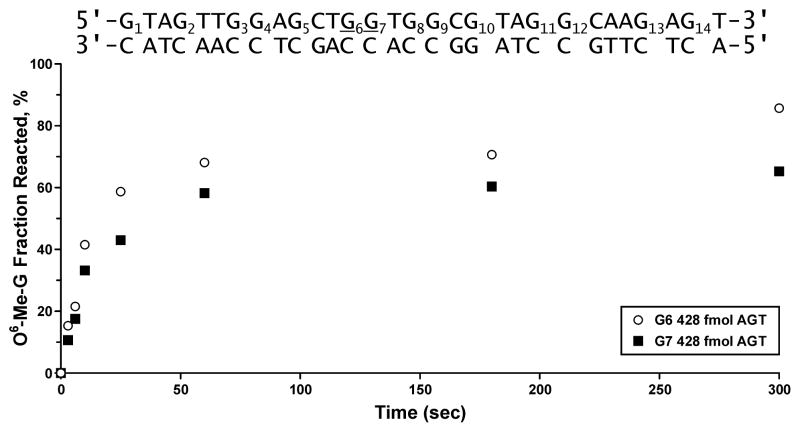

The time courses of AGT-induced demethylation of O6-Me-G6 K-ras and O6-Me-G7 K-ras (corresponding to the first and second guanines of K-ras codon 12, see Table 1) were statistically equivalent according to ANOVA analysis (p = 0.3431) (Figure 7). Second order rate constants for AGT repair of O6-Me-dG adducts located at the first and second positions of the K-ras codon 12 (5'-G6G7T-3') were calculated as 1.4 × 107 M−1s−1 and 7.4 × 106 M−1s−1, respectively. Interestingly, the kt versus t plots exhibited non-linear behavior at the later time points, suggesting that the demethylation reaction does not exactly follow the second order kinetics. This is not surprising, given the multiplicity of the steps involved in the AGT-mediated repair of O6-alkylguanines, including the binding of AGT protein to its DNA substrate, nucleotide flipping into the active site, and alkyl transfer (31).

Figure 7.

Time course for AGT repair of O6-Me-G located at the first and second position of K-ras codon 12. Synthetic DNA duplexes containing a single O6-Me-G residue at either G6 or G7 of the (+) strand: 5'-G1TA G2TT G3G4A G5CT G6G7T G8G9C G10TA G11G12C AAG13 AG14T-3' (500 fmol) were combined with human recombinant AGT (450 fmol). The reactions were terminated at different times by the addition of HCl, and the samples were acid hydrolyzed to release purine bases. Unrepaired O6-Me-G was quantified by HPLC-ESI+-MS/MS using O6- CD3-G as an internal standard.

The general trend for O6-Me-G repair by recombinant AGT within K-ras derived duplex (Figure 7) is consistent with earlier studies for H-ras-derived duplexes (20,21,24). It has been previously reported that adducts formed at the first guanine of H-ras codon 12 ([O6-Me-G]GA) were repaired much more efficiently than those at the second guanine (G[O6-Me-G]A) ) (20,21,24). However, unlike previous results for H-ras derived sequences, we detected only a slight difference between the extent of repair observed at the neighboring guanine bases (Figure 7). This discrepancy may be a result of different local DNA sequence within H-ras codon 12 (GGA) and K-ras codon 12 investigated in the present study (GGT), which is likely to affect local DNA conformation. In addition, while Meyer and collaborators employed a large excess of AGT relative to O6-Me-G in order to achieve first-order conditions (24), our experiments were performed with protein to DNA molar ratios favoring second-order kinetics (AGT: O6-Me-G = 0.1 – 1.7).

In summary, our results for AGT-mediated repair of O6-Me-dG located at different sites within K-ras gene derived DNA duplexes reveal similar demethylation rates at all positions examined. Moderate sequence specificity for O6-Me-dG repair by AGT observed in the present investigation is consistent with the recent kinetic, structural and spectroscopic studies. In the current kinetic model, AGT rapidly scans DNA, flipping O6-Me-dG residues with little specificity over normal Gs (17,31). Since the rate limiting step of the methyl group transfer from DNA to the active site cysteine takes place following flipping of the O6-Me-dG nucleotide out of the DNA duplex (17,31), neighboring nucleobases are unlikely to participate in alkyl transfer and therefore are expected to have limited effect on the repair rates. In contrast, local DNA sequence context appears to play a key role in determining the yields of methylated lesions at a given guanine. We have previously demonstrated that both O6-Me-dG and O6-POB-dG lesions of NNK are formed preferentially at the second position of K-ras codon 12 (GGT), a major mutational hotspot for G→A transition mutations observed in lung tumors (32). Taken together, these observations suggest that preferential adduct formation, rather than repair by AGT, may be the determining factor for K-ras codon 12 mutagenesis following exposure to methylating agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yan Zhang, Zhong-ze Li, and Joseph Koopmeiners at the University of Minnesota Biostatistics Core for statistical analyses of our data, Brock Matter for assistance with mass spectrometry, and Gregory Janis for editorial help. Funding for this research was provided by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA095039).

Abbreviations

- AGT

O6-alkylguanine-DNA-alkyltransferase

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CID

collision induced dissociation

- DBU

1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene

- DTT

D,L-dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- KLH

Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin

- LC

liquid chromatography

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- NNK

4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

- O6-Alk-dG

O6-alkyl-2'-deoxyguanosine

- O6-CD3-dG

O6-trideuteromethyl-2'-deoxyguanosine

- O6-CD3-G

O6-trideuteromethylguanine

- O6-Me-dG

O6-methyl-2'-deoxyguanosine

- O6-Me-G

O6-methylguanine

- O6-Me-dG-CE phosphoramidite

5'-dimethoxytrityl-N-isobutyryl-O6-methyl-2'-deoxyguanosine- 3'-[(2-cyanoethyl)-(N,N-diisopropyl)]-phosphoramidite

- O6-POB-dG

O6-[4-oxo-(3-pyridyl)but-1-yl]-2'-deoxyguanosine

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

References

- 1.Rodenhuis S, Slebos RJ, Boot AJ, Evers SG, Mooi WJ, Wagenaar SS, van Bodegom PC, Bos JL. Incidence and possible clinical significance of K-ras oncogene activation in adenocarcinoma of the human lung. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5738–5741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodenhuis S, Slebos RJ. Clinical significance of ras oncogene activation in human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2665s–2669s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westra WH, Baas IO, Hruban RH, Askin FB, Wilson K, Offerhaus GJ, Slebos RJ. K-ras oncogene activation in atypical alveolar hyperplasias of the human lung. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2224–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westra WH, Slebos RJ, Offerhaus GJ, Goodman SN, Evers SG, Kensler TW, Askin FB, Rodenhuis S, Hruban RH. K-ras oncogene activation in lung adenocarcinomas from former smokers. Evidence that K-ras mutations are an early and irreversible event in the development of adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 1993;72:432–438. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930715)72:2<432::aid-cncr2820720219>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mills NE, Fishman CL, Rom WN, Dubin N, Jacobson DR. Increased prevalence of K-ras oncogene mutations in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1444–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slebos RJ, Hruban RH, Dalesio O, Mooi WJ, Offerhaus GJ, Rodenhuis S. Relationship between K-ras oncogene activation and smoking in adenocarcinoma of the human lung. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1024–1027. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.14.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegfried JM, Gillespie AT, Mera R, Casey TJ, Keohavong P, Testa JR, Hunt JD. Prognostic value of specific K-ras mutations in lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:841–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronai ZA, Gradia S, Peterson LA, Hecht SS. G to A transitions and G to T transversions in codon 12 of the Ki-ras oncogene isolated from mouse lung tumors induced by 4- (methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and related DNA methylating and pyridyloxobutylating agents. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:2419–2422. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.11.2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann D, Hecht SS. Nicotine-derived N-nitrosamines and tobacco-related cancer: current status and future directions. Cancer Res. 1985;45:935–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann D, Rivenson A, Amin S, Hecht SS. Dose-response study of the carcinogenicity of tobacco-specific N- nitrosamines in F344 rats. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1984;108:81–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00390978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hecht SS, Chen CB, Young R, Lin D, Hoffmann D. IARC Sci Publ. 1980. Metabolism of the tobacco specific nitrosamines, N'-nitrosonornicotine and 4-(N-methyl-N-nitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone; pp. 755–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hecht SS. DNA adduct formation from tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Mutat Res. 1999;424:127–142. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson LA, Hecht SS. O6-methylguanine is a critical determinant of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1- (3-pyridyl)-1-butanone tumorigenesis in A/J mouse lung. Cancer Res. 1991;51:5557–5564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Essigmann JM, Loechler EL, Green CL. Genetic toxicology of O6-methylguanine. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1986;209A:433–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pegg AE. Properties of mammalian O6-alkylguanine-DNA transferases. Mutat Res. 1990;233:165–175. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(90)90160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demple B, Jacobsson A, Olsson M, Robins P, Lindahl T. Repair of alkylated DNA in Escherichia coli. Physical properties of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:13776–13780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniels DS, Woo TT, Luu KX, Noll DM, Clarke ND, Pegg AE, Tainer JA. DNA binding and nucleotide flipping by the human DNA repair protein AGT. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:714–720. doi: 10.1038/nsmb791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pegg AE. Repair of O6-alkylguanine by alkyltransferases. Mutat Res. 2000;462:83–100. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasimas JJ, Dalessio PA, Ropson IJ, Pegg AE, Fried MG. Active-site alkylation destabilizes human O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase. Protein Sci. 2004;13:301–305. doi: 10.1110/ps.03319404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolan ME, Oplinger M, Pegg AE. Sequence specificity of guanine alkylation and repair. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9:2139–2143. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.11.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Georgiadis P, Smith CA, Swann PF. Nitrosamine-induced cancer: selective repair and conformational differences between O6-methylguanine residues in different positions in and around codon 12 of rat H-ras. Cancer Res. 1991;51:5843–5850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bender K, Federwisch M, Loggen U, Nehls P, Rajewsky MF. Binding and repair of O6-ethylguanine in double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides by recombinant human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase do not exhibit significant dependence on sequence context. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2087–2094. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.11.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scicchitano D, Jones RA, Kuzmich S, Gaffney B, Lasko DD, Essigmann JM, Pegg AE. Repair of oligodeoxynucleotides containing O6-methylguanine by O6- alkylguanine-DNA-alkyltransferase. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7:1383–1386. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.8.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer AS, McCain MD, Fang Q, Pegg AE, Spratt TE. O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferases repair O6-methylguanine in DNA with Michaelis-Menten-like kinetics. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:1405–1409. doi: 10.1021/tx0341254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaney JC, Essigmann JM. Context-dependent mutagenesis by DNA lesions. Chem Biol. 1999;6:743–753. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)80021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L, Xu-Welliver M, Kanugula S, Pegg AE. Inactivation and degradation of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase after reaction with nitric oxide. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3037–3043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziegel R, Shallop A, Upadhyaya P, Jones R, Tretyakova N. Endogenous 5-methylcytosine protects neighboring guanines from N7 and O6-methylation and O6-pyridyloxobutylation by the tobacco carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Biochemistry. 2004;43:540–549. doi: 10.1021/bi035259j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajesh M, Wang G, Jones R, Tretyakova N. Stable isotope labeling-mass spectrometry analysis of methyl- and pyridyloxobutyl-guanine adducts of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in p53-derived DNA sequences. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2197–2207. doi: 10.1021/bi0480032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh R, Farmer PB. Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry: the future of DNA adduct detection. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:178–196. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spratt TE, De los Santos H. Reaction of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase with O6-methylguanine analogues: evidence that the oxygen of O6-methylguanine is protonated by the protein to effect methyl transfer. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3688–3694. doi: 10.1021/bi00129a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zang H, Fang Q, Pegg AE, Guengerich FP. Kinetic analysis of steps in the repair of damaged DNA by human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30873–30881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505283200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziegel R, Shallop A, Jones R, Tretyakova N. K-ras gene sequence effects on the formation of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1- (3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK)-DNA adducts. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:541–550. doi: 10.1021/tx025619o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.