Abstract

Kinetic parameters and the role of cytochrome c3 in sulfate, Fe(III), and U(VI) reduction were investigated in Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. While sulfate reduction followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Km = 220 μM), loss of Fe(III) and U(VI) was first-order at all concentrations tested. Initial reduction rates of all electron acceptors were similar for cells grown with H2 and sulfate, while cultures grown using lactate and sulfate had similar rates of metal loss but lower sulfate reduction activities. The similarities in metal, but not sulfate, reduction with H2 and lactate suggest divergent pathways. Respiration assays and reduced minus oxidized spectra were carried out to determine c-type cytochrome involvement in electron acceptor reduction. c-type cytochrome oxidation was immediate with Fe(III) and U(VI) in the presence of H2, lactate, or pyruvate. Sulfidogenesis occurred with all three electron donors and effectively oxidized the c-type cytochrome in lactate- or pyruvate-reduced, but not H2-reduced cells. Correspondingly, electron acceptor competition assays with lactate or pyruvate as electron donors showed that Fe(III) inhibited U(VI) reduction, and U(VI) inhibited sulfate loss. However, sulfate reduction was slowed but not halted when H2 was the electron donor in the presence of Fe(III) or U(VI). U(VI) loss was still impeded by Fe(III) when H2 was used. Hence, we propose a modified pathway for the reduction of sulfate, Fe(III), and U(VI) which helps explain why these bacteria cannot grow using these metals. We further propose that cytochrome c3 is an electron carrier involved in lactate and pyruvate oxidation and is the reductase for alternate electron acceptors with higher redox potentials than sulfate.

The electron transfer pathways and participation of the periplasmic cytochrome c3 in sulfate reduction have been intensively investigated (2, 5, 12, 28, 31, 33, 51). Sulfate-reducing bacteria oxidize lactate or pyruvate to acetate, hydrogen, and CO2 (37, 38, 64). An H2 cycling model was proposed (34) to explain H2 production, but it could only account for 48% of the electrons transported from lactate (32). Subsequently, a unified model described lactate oxidation to acetate by combining three pathways, one involving H2 cycling and two using only electron carriers (32).

The most intensely studied of these carriers in Desulfovibrio vulgaris are cytochromes (53, 59), with the foremost being the periplasmic cytochrome c3 (31, 44). The latter is used as a biomarker for Desulfovibrio spp. (31). Similarities that exist between cytochrome c3 from different strains include heme 4 interacting with the hydrogenase for electron transfer (1, 5, 15, 40), as well as an N-terminal amino acid sequence extension for periplasm export (1, 15, 19, 61, 62).

Recently, a periplasmic-facing but membrane-associated cytochrome c3 was found in D. vulgaris Hildenborough (58) with similar E0 values and reduced minus oxidized spectrum to the soluble protein (7). Rather than being regarded as a general electron carrier, this protein is speculated to function with the high-molecular-weight complex (hmc) as a membrane-bound oxidoreductase complex, since they are part of the same operon. The periplasmic cytochrome c3, on the other hand, functions in the reduction of a variety of electron acceptors, such as O2 (11, 12, 18, 28), Cr(VI) (24), Fe(III) (22), and U(VI) (27).

We are specifically interested in how sulfate-reducing bacteria reduce U(VI) to U(IV). While these microorganisms can tolerate up to 24 mM uranium (22), most species cannot grow using it as the sole electron acceptor (56). Exceptions are D. vulgaris UFZ B 490 (41) and Desulfotomaculum reducens (54). Reports of the kinetic parameters for U(VI) reduction show enhanced reduction rates in the presence of sulfate by a sulfate-reducing enrichment culture (specific activity of 23 μM min−1 mg of cells−1; apparent Km of 250 μM) (49, 50), while Desulfovibrio desulfuricans showed no such stimulation (specific activity of 30 μM min−1 mg of cells−1; Km of 500 μM) (25, 50). In both cases, sulfate and uranium were reduced concomitantly. Whereas D. desulfuricans showed zero-order kinetics for sulfide production with or without U(VI), loss of the latter was first-order (49), indicating that U reduction is not a typical enzymatic reaction.

Given the ability to reduce numerous electron acceptors, along with first-order U-reduction kinetics, this cytochrome may be more than a simple electron carrier. Here, we report for the first time that cytochrome c3 is likely involved in sulfate reduction from lactate and pyruvate, but not from H2, in D. vulgaris. Further, Fe(III) and U(VI) completely inhibit lactate- and pyruvate-mediated sulfate reduction, but only slow this process when H2 is the electron donor. By using washed cells in reduction assays and cytochrome spectra, we propose that electrons derived from organic donor oxidation may flow through two or more pathways, one of which involves cytochrome c3, while the latter is not implicated in H2-dependent sulfate reduction. Finally, we present a modified electron transport pathway, for which both the present work and previous reports agree.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth and preparation of washed cell suspensions.

Methods for the preparation and use of anaerobically prepared media and solutions were as described previously (3). A headspace of 80% N2-20% CO2 was used, except when hydrogen was the electron donor, where the headspace was 80% H2-20% CO2. All plasticware and other materials were incubated overnight inside an anaerobic chamber prior to use.

Cultures of wild-type D. vulgaris Hildenborough (ATCC 29579) and its hyd (42) and hmc (14, 17, 43) mutants (a gift from G. Voordouw) were grown with the medium previously described (35) at 37°C. The hyd (lacking the Fe-only hydrogenase) and hmc mutants were grown in the presence of 10 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. Cultures (1 liter) were grown with either 20 mM Na-lactate or H2 (80% H2-20% CO2 headspace) as the electron donor and Na-sulfate (20 mM) as the electron acceptor, or fermentatively with 20 mM Na-pyruvate. All cultures were grown in 2-liter Pyrex bottles sealed with a rubber stopper that was fitted with a serum tube and a serum stopper. Once grown (A660 of ∼0.80; late log phase), cultures were dispensed into centrifuge bottles inside of an anaerobic chamber (Coy Industries, Ann Arbor, Mich.), sealed, and then centrifuged (27,000 × g, 20 min, 10°C). Cells used for experiments with lactate or pyruvate as the electron donor were washed three times by centrifugation as above, resuspending the pellet in 30 mM NaHCO3 buffer (pH 6.8, under an 80% N2-20% CO2 gas phase) (27). After washing, the pellet was resuspended in 15 ml of the buffer per liter of culture to yield a cell concentration of 8 to 8.75 mg of protein/ml of buffer. When H2 was the electron donor, cysteine-HCl (0.25 g liter−1; 1.6 mM) was added to the buffer, as it is required to facilitate H2-mediated sulfate reduction (25). Cysteine-HCl was not added to the buffer when either lactate or pyruvate was tested.

Modeling of U(VI) and Fe(III) concentrations.

The major species of U(VI) and Fe(III) in our experiments were determined using Phreeqci (version 2.7) (http://typhoon.mines.edu/zipfiles/phreeqc.htm) with the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory database. All chemical components added to the medium were incorporated into the model to calculate the chemical form of electron acceptor present. The model was also used to argue that the electron acceptors remained in solution. Concentrations of 2 mM each of U(VI) and Fe(III) were used to model the reduction experiments.

Electron acceptor reduction assays.

All manipulations were conducted in an anaerobic chamber except for electron acceptor measurement. Experiments were conducted in duplicate.

The reduction of sulfate, Fe(III), and U(VI) by washed cell suspensions was followed over time, and progress curves were constructed to determine the kinetic parameters and to characterize the ability of the organism to use individual, or combinations of, electron acceptors. Each assay was performed in 160-ml serum bottles sealed with rubber serum stoppers. Each serum bottle contained 100 ml (final volume) of 30 mM NaHCO3 buffer (pH 6.8) with an 80% N2-20% CO2 gas phase, except when hydrogen was the electron donor, where the gas phase was 80% H2-20% CO2. When hydrogen was the electron donor, the buffer contained 1.6 mM cysteine · HCl. U(VI) (as uranyl carbonate), FeCl3, or Na2SO4 was added from filter-sterilized, anaerobic stock solutions prepared in the 30 mM NaHCO3 buffer. Uranyl-carbonate was prepared (26) and quantified by using a kinetic phosphorescence analyzer (model KPA-11; Chemchek Instruments, Inc.) as described previously (4, 30). The reaction was started by the addition of 8 ml of the washed cell suspension to give a final protein concentration of 0.65 to 0.71 mg of protein per ml. For all assays, cells were grown in medium with the same electron donor as was used in the assay. For example, if the H2-mediated loss of sulfate, Fe(III), or U(VI) was studied, the cells were grown with H2-CO2 and sulfate. In order to preclude H2 phase-transfer limitations and to ensure that electron acceptors remained in solution, the cell density was kept low (as indicated above) and the reaction mixture was continuously stirred. Stir bars were placed in serum bottles which were then flushed with N2-CO2, sealed, and autoclaved (121°C, 20 min).

After addition of the washed cell suspension, the loss of the electron acceptor was followed over time by removing periodically 0.2 ml of the cell suspension. The sample was injected immediately into 0.2 ml of anaerobic 1.2 M HCl and centrifuged (13,000 × g, 10 min, 20°C). The supernatant was removed for metal or sulfate quantitation. The loss of U(VI) was monitored as described above. Sulfate concentrations were measured by using a Dionex DX-500 ion chromatograph with an AS-4A anion column as previously described (57). Levels of Fe(II) and Fe(III) were determined by a colorimetric method (23). Lactate was measured using a Dionex DX-500 chromatography system with an AS-11A anion column (48). Protein was determined by adding 0.2 ml of cell suspension to 0.2 ml of 1 N NaOH and incubating at 37°C for 4 h. The protein content of these cell preparations was quantitated using the bicinchoninic protein assay (Pierce Chemical Co.).

In order to ensure that cysteine did not affect metal reduction rates, control assays without cells were also performed as above for each metal, with cysteine present in the buffer. Also, assays with cells suspended in the cysteine-containing buffer and without the addition of an electron acceptor were conducted to confirm that cysteine was not metabolized under the conditions of our assays.

Kinetics of Fe(III), sulfate, and U(VI) reduction.

The kinetics of sulfate reduction were determined by incubating cell suspensions prepared as described above at concentrations of 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mM Na2SO4 with 20 mM Na-lactate and measuring sulfate loss over time. The apparent Km and Vmax associated with sulfate reduction were determined by calculating the initial reduction rate and fitting this rate to the Michaelis-Menten equation. Sulfate reduction kinetics were also determined by monitoring sulfate loss over the entire time course and using the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation (47). The Michaelis-Menten equation was then fitted to the progress curve data using Matlab software, where the apparent Km and Vmax were again calculated. In each case, the two methods were in good agreement with the latter results presented here. Each experiment was performed twice with duplicate bottles. Fe(III) reduction kinetics were determined in a similar manner with a starting concentration of 2 mM Fe(III) and using the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation (47).

In order to determine the kinetic parameters of U(VI) reduction, assays were carried out as described above at initial U(VI)-carbonate concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 5 mM, with 20 mM lactate as electron donor. Samples were removed every 20 min for the first 6 h and periodically thereafter until U(VI) reduction ceased. Kinetic parameters were then calculated by using both initial rate measurements as well as the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation (47).

Competition for electron acceptors.

Competition assays were performed to see if the wild-type strain of D. vulgaris could reduce U(VI) or Fe(III) in the presence of sulfate. If sulfate loss was somehow inhibited while metal reduction occurred, this would argue that a common electron transfer protein was involved in both sulfate and metal reduction. Each assay was carried out (as described above) with 20 mM lactate (80% N2-20% CO2) or H2 (80% H2-20% CO2) as the electron donor, with 2 mM each of Fe(III) and U(VI), Fe(III) and sulfate, or U(VI) and sulfate. Positive controls used 2 mM Fe(III), U(VI), or sulfate alone, and assays with heat-killed cells served as negative controls. The assays were sampled over time as described above.

Inhibition of sulfate reduction versus U(VI) or Fe(III) reduction.

Molybdate has often been shown to inhibit sulfate reduction, with the proposed site of inhibition being the adenosine triphosphate sulfurylase (36). In order to determine if this enzyme may be involved in U(VI) and/or Fe(III) reduction, 20 mM Na-molybdate was added to reduction assay mixtures with 2 or 20 mM Na2SO4, 2 mM uranyl-carbonate, or 2 mM FeCl3. Assays were performed as described above using the wild-type strain of D. vulgaris with 20 mM Na-lactate as the electron donor.

Effect of periplasm removal on electron acceptor reduction.

The proposed U(VI) reductase, and most likely the Fe(III) reductase (27), is the periplasmic cytochrome c3. The periplasm of lactate and sulfate-grown, wild-type D. vulgaris cells was removed (2) to determine if periplasmic components were required for metal and sulfate reduction. The cells were resuspended in 15 ml of original culture liter−1 in 30 mM NaHCO3, pH 6.8. Cells were inspected microscopically to ensure that cell lysis had not taken place.

Lactate dehydrogenase activity (a cytoplasmic enzyme) of treated cells demonstrated that the cytoplasm was intact after this treatment. Treated cells were assayed as described above with 20 mM Na-lactate as the electron donor and 2 mM methyl viologen as electron acceptor. Lactate was measured as described above. Methyl viologen reduction was measured spectrophotometrically at 560 nm (46, 63). The effectiveness of this treatment in removal of the periplasm was determined by the loss of the cytochrome c3 spectrum from the treated cell suspension (see below).

Cytochrome spectra.

The oxidation of the periplasmic c-type cytochrome via sulfate, U(VI), or Fe(III) was determined for all three strains of D. vulgaris by using a modified reduced minus oxidized spectral method (29). Sample cuvettes were constructed with 12- by 75-mm glass test tubes, sealed with 00 butyl rubber stoppers, and flushed with N2-CO2 (80:20) or H2-CO2 (80:20) (10). A spectrophotometer (Beckman DU64; Beckman Coulter, Inc.) scanned the assay mixture from 400 to 650 nm at 500 nm/min. To generate the cytochrome spectra, we first added 0.2 ml of the washed cell suspension (about 1.7 mg of protein) to 1.7 ml of sterile 30 mM NaHCO3 buffer. Cysteine was present in the buffer if H2 was used as the electron donor (see above). A reductant, Na-dithionite, 40 μM lactate, pyruvate under N2-CO2 (80:20), or a headspace of H2-CO2 (80:20) was then added. The cells were allowed to incubate in the dark (1 h), and the cuvette was scanned to obtain the reduced spectrum. Prior to electron acceptor addition, the H2-CO2 (80:20) gas phase (if used) was aseptically exchanged by venting with sterile needles to N2-CO2 (80:20) to limit electron generation and facilitate cytochrome oxidation. Then, 0.1 ml of 25 mM Na2SO4, uranyl-carbonate, or FeCl3 (2 mM final concentration) was added, and the spectrum was recorded immediately and then periodically thereafter for 2 h. The reduced spectrum was used as the baseline scan by the spectrophotometer software, yielding an inverted spectrum which was reversed for presentation in Fig. 4. A positive control used H2-reduced cell suspensions where the stopper was removed after incubation (1 h) and replaced with sterile cotton so that the cytochrome was oxidized by exposure to air. Negative controls used either no electron donor in the presence of all three electron acceptors or H2-reduced cell suspensions amended with 0.1 ml of assay buffer instead of electron acceptor.

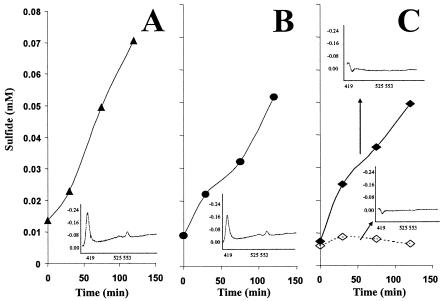

FIG. 4.

Production of sulfide monitored over time with concomitant cytochrome spectra. Sulfidogenesis was found when lactate (▴) (A), pyruvate (•) (B), and H2 with cysteine (♦) (C), but not H2 without cysteine (⋄), were used to reduce the cytochrome. Inserts show the spectrum obtained after 30 min from lactate and pyruvate and after 2 h from H2 with and without the addition of cysteine.

Sulfidogenic activity and cytochrome oxidation spectra.

Experiments to determine the cytochrome spectra occurring as a result of the oxidation of periplasmic c-type cytochrome with sulfate were conducted simultaneously with the measurement of sulfide formation. The latter measurements were done to determine if sulfidogenesis occurred without cytochrome involvement. The spectral assays were performed as described above; however, immediately prior to scanning the oxidized spectrum, 0.1 ml of the cuvette contents was removed via syringe and needle and added to 0.5 ml of 4% Zn-acetate to quantify sulfide (8).

RESULTS

Use of HCl to preserve electron acceptor concentrations.

Quantitation of U(VI) with different HCl concentrations showed that the KPA response was quenched with increasing HCl concentration (data not shown). However, little signal loss occurred with 6 mM HCl (final concentration). The addition of 1.2 M HCl (1:1 [vol/vol]) to the sample with subsequent 100-fold dilution in water prior to analysis effectively preserved the sample and avoided quenching.

Modeling of U(VI) and Fe(III) concentrations.

Computer (Phreeqci) modeling of solutions of 2 mM uranyl (UO22+) or FeCl3 in 30 mM NaHCO3, pH 6.8, indicated two major species of each electron acceptor. In the case of uranyl, UO2(CO3)34− (1.079 mM) and UO2(CO3)22− (0.787 mM) accounted for 93.3% of the U(VI) added. For Fe(III), Fe(OH)3 (1.448 mM, likely as a mineral based on the saturation index) and Fe(OH)2+ (0.550 mM) made up greater than 99% of the Fe(III) present. These analyses indicated that rather than several species being involved, two uranyl species and Fe(OH)2+ were the predominant soluble forms. Since Fe(III) was completely reduced to Fe(II) in the reduction assays (see Fig. 2), it is likely that the Fe(OH)3 dissolves slowly as the equilibrium of the reaction is altered by microbial action.

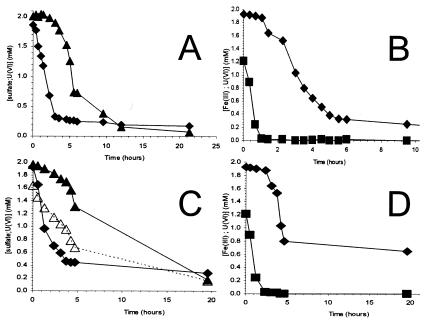

FIG. 2.

Experimental results in which washed cell suspensions of D. vulgaris were incubated in the presence of competing electron acceptors. (A and B) Lactate was used as the electron donor with U(VI) (♦) and sulfate (▴) (both at 2 mM) as electron acceptors (A) or with Fe(III) (▪) and U(VI) (♦) as electron acceptors (B). (C and D) H2 was the electron donor with U(VI) (♦) and sulfate (▴) or sulfate alone (▵) (C), or with Fe(III) (▪) and U(VI) (♦) (D).

Kinetics of Fe(III), sulfate, and U(VI) reduction.

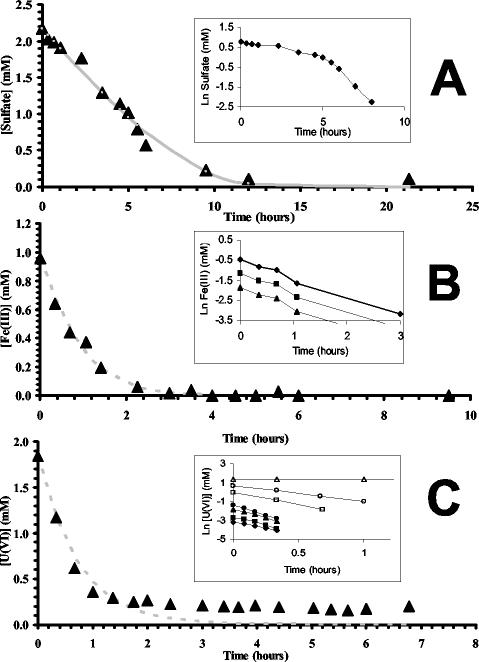

Progress curves for sulfate consumption followed apparent Michaelis-Menten kinetics with 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mM sulfate (data not shown) as well as with 2 mM sulfate (Fig. 1A). This is shown most obviously in the insert, where the semilogarithmic plot of the same data clearly shows zero- and first-order decay regions. Analysis of the data revealed an apparent Km of 0.22 mM and an apparent Vmax of 0.35 mM h−1. Substantially different kinetics were observed when the same culture was incubated with Fe(III) or U(VI). Since the geochemical model showed that the major Fe(III) species was above the saturation index at concentrations of 2 mM FeCl3, 1 mM was instead used in these experiments so that the Fe(OH)3 concentration was closer to the saturation index. At an initial Fe(III) concentration of 1 mM, no hint of saturation was observed (Fig. 1B). A semilogarithmic plot revealed that Fe(III) reduction was a first-order process with a proportionality constant ranging from 0.89 to 0.91 h−1 at 1 mM Fe(III). Similarly, when the rate of U(VI) reduction was determined, first-order kinetics were also observed at concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 2.0 mM (Fig. 1C). At these U(VI) concentrations, the first-order decay rate ranged from 1.65 to 4.2 h−1 (insert). When the U(VI) concentration was 5 mM, U(VI) reduction was inhibited and a measurable rate could not be determined (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the kinetics of sulfate (A), Fe(III) (B), and U(VI) (C) reduction by washed cell suspensions of wild-type D. vulgaris. The inserts are semilogarithmic plots of the respective reduction processes for sulfate (2 mM), U(VI) (0.05 to 5.0 mM), and Fe(III) (0.2 to 1.0 mM). The solid line in panel A is a simulation of the sulfate depletion curve based on the Michaelis-Menten equation, using the derived Km and Vmax values and an initial starting concentration of 2 mM. First-order decay curves (broken lines) modeled in panels B and C are based on the measured decay coefficient and the given starting concentration. The data shown are from a single progress curve and are not an average of duplicate data.

Electron acceptor reduction assays.

The reduction of U(VI), Fe(III), and sulfate was monitored over time in washed cell suspensions incubated with different electron donors. Wild-type D. vulgaris cells grown with H2 and sulfate and assayed with H2 as electron donor had similar initial rates of sulfate, Fe(III), and U(VI) reduction. However, eight times more electrons were required for an equivalent amount of sulfate to be reduced than Fe(III), while four times more electrons were required relative to U(VI) (Table 1). This indicates that the rates of substrate oxidation and consequent electron transfer processes are far higher with sulfate than with metals as electron acceptors. The rate of Fe(III) and U(VI) reduction was similar with lactate, compared to H2, as a donor. However, the rate of sulfate reduction with lactate was only 62% of that observed when H2 served as a donor. This suggested that the sulfate reduction process was, in some way, different from that involved in metal reduction when H2 was the source of electrons. The relative Fe(III) and U(VI) reduction activities were lower with fermentatively grown cells using pyruvate as the donor than with lactate as electron donor in sulfate-grown cells. There was no appreciable difference in sulfate reduction rates with lactate versus pyruvate as electron donor. The absence of the Fe-only hydrogenase or the hmc complex reduced H2-mediated sulfate reduction rates by 50 and 35%, respectively, while much less of a difference was seen compared to the wild-type strain when lactate or pyruvate served as electron donor. Conversely, the Fe-only hydrogenase (hyd) mutant showed increased Fe(III) and U(VI) reduction rates with H2 as the electron donor (85 and 48%, respectively), with smaller increases when lactate was the donor (40 and 16%, respectively) compared to the wild-type strain (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of initial electron acceptor reduction rates when grown and assayed with H2, lactate, or pyruvate as electron donor

| Electron acceptor | Initial rate (μM min−1 · mg of protein−1) with electron donor

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | Lactate | Pyruvateb | |

| Fe(III) | |||

| Wild type | 12.2 ± 0.41c (12)d | 12.3 ± 0.21 (12) | 7.7 ± 0.12 (8) |

| hyda mutant | 22.6 ± 0.52 | 17.2 ± 0.34 | 5.8 ± 0.09 |

| hmc mutant | 12.9 ± 0.33 | 10.3 ± 0.44 | 6.7 ± 0.13 |

| U(VI) | |||

| Wild type | 16.0 ± 0.60 (32) | 15.9 ± 0.32 (32) | 4.8 ± 0.24 (10) |

| hyd mutant | 23.7 ± 0.43 | 18.4 ± 0.23 | 4.8 ± 0.18 |

| hmc mutant | 16.3 ± 0.22 | 14.4 ± 0.19 | 6.4 ± 0.43 |

| Sulfate | |||

| Wild type | 11.8 ± 0.49 (96) | 7.3 ± 0.46 (58) | 7.1 ± 0.23 (56) |

| hyd mutant | 6.0 ± 0.43 | 8.0 ± 0.52 | 4.6 ± 0.36 |

| hmc mutant | 7.7 ± 0.69 | 5.2 ± 0.34 | 8.3 ± 0.22 |

Lacking Fe-only hydrogenase.

Pyruvate-grown cells were fermentatively grown.

Initial reduction rates and standard errors were calculated from two assays performed in duplicate (a total of four values).

Values in parentheses indicate the equivalent number of electrons transferred over the time course (micromolar per minute per milligram of protein).

Competition for electron acceptors.

The periplasmic cytochrome c3 reportedly functions both as the U(VI) reductase (27) and as an electron carrier for sulfate reduction (5, 52). Assays were performed to determine if the presence of one electron acceptor would impact the reduction of another electron acceptor. The reduction rates obtained with Fe(III), U(VI), and sulfate alone were similar to those in the previous experiment (Table 1), and no activity was observed in heat-killed controls (data not shown). When lactate was the electron donor, sulfate reduction was completely inhibited by the presence of U(VI) until the rate of loss of U(VI) began to decrease (Fig. 2A). However, with H2 as electron donor, U(VI) only slowed sulfate reduction (59.7% inhibition) until U(VI) loss ceased (Fig. 2C). U(VI) reduction was halted by the presence of Fe(III) whether H2 or lactate was the electron donor (Fig. 2B and D).

Inhibition of sulfate reduction versus U(VI) and Fe(III) reduction.

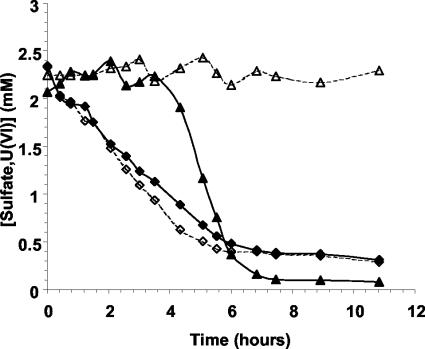

The addition of 20 mM Na-molybdate inhibited lactate-mediated sulfate reduction with both 2 mM (Fig. 3) and 20 mM (data not shown) Na2SO4 as expected. However, the presence of molybdate did not influence Fe(III) (data not shown) or U(VI) reduction (Fig. 3). This indicated that electron transfer to Fe(III) and U(VI) does not involve components that are inhibited by molybdate.

FIG. 3.

Graph showing the reduction of sulfate (triangles) and U(VI) (diamonds) by washed cell suspensions of wild-type D. vulgaris. Sulfate reduction was completely inhibited by 20 mM molybdate (▵) with transient inhibition of sulfate reduction by the presence of 2 mM U(VI) (▴). U(VI) reduction in the presence of sulfate was not inhibited by molybdate (⋄) compared to U(VI) reduction in the absence of molybdate (♦).

Effect of periplasm removal on electron acceptor reduction.

In order to confirm that the contents of the periplasm were essential for electron transport for Fe(III), U(VI), and sulfate reduction, this part of the cell was removed and the periplasmless cells were tested against intact ones. Intact cells reduced all three electron acceptors at rates similar to those seen in previous assays, while cells with the periplasm removed had no activity (data not shown). Further, no cytochrome difference spectra were detected with lactate and Fe(III), U(VI), or sulfate after treatment, indicating a loss of periplasmic contents. The cytoplasm of the treated cells was still intact, as lactate was oxidized with the concomitant reduction of methyl viologen at rates similar to intact cells (data not shown).

Cytochrome c3 spectra.

The difference spectra for all three strains of D. vulgaris showed a Soret peak at 419 nm and α and β peaks at 553 and 525 nm, respectively, which is consistent with cytochrome c3 as the major c-type cytochrome in the cell (31, 55). Reduction of the cytochrome using dithionite, H2-CO2, lactate, and pyruvate was successful after a 1-h incubation, as reduced minus oxidized spectra were detected when the cuvettes were subsequently exposed to air. The addition of 2 mM Fe(III), U(VI), or sulfate caused immediate oxidation of the cytochrome when reduced with lactate, pyruvate, or dithionite, confirming the involvement of this protein in electron transfer from organic donors. The coupling of H2 with the electron acceptors was not as straightforward. The addition of 2 mM Fe(III) or U(VI) to H2-reduced cells caused an immediate oxidation of the cytochrome, but oxidation was not observed with sulfate addition even after a 2-h incubation (Fig. 4). However, the subsequent addition of 2 mM Fe(III) or U(VI) gave an immediate difference spectrum, suggesting that the cytochrome remained in the reduced state while sulfate reduction proceeded (data not shown). We then carried out sulfide production assays to be certain that sulfate was reduced when it was present as the oxidant. In all cases, sulfate reduction occurred as determined by the production of sulfide (Fig. 4). These data suggest that the predominant c-type cytochrome involved in pyruvate- or lactate-coupled sulfate reduction (presumably cytochrome c3) is not involved in H2-mediated sulfate reduction.

DISCUSSION

Several Desulfovibrio spp. are capable of reducing both Fe(III) (22) and U(VI) (50) but are unable to grow using these metals as terminal electron acceptors (56). Fe(III) reduction is known to occur via the periplasmic cytochrome c3 (22), and both a soluble hydrogenase and this cytochrome were required for in vitro U(VI) reduction (27). Here, we report that U(VI) reduction (up to 2 mM) was possible, but rates dropped sharply as concentrations fell below 300 μM, as previously observed (50). Our results using various kinetic models are similar to previous observations in which both U(VI) (49, 50) and Fe(III) (20) reduction were shown to be first-order processes. A half-saturation constant of 29 mM was calculated for reduction of Fe(III) by Shewanella putrefaciens CN32 (21). Sulfate-reducing bacteria are potentially important actors for in situ uranium bioremediation. Since they cannot derive energy from U(VI) reduction (56) and the substrate concentration alone determines the reaction rate, a reaction carried out by these microorganisms will be highly predictable (47).

A comparison of the Soret, α, and β peaks from our cytochrome spectra with the spectral properties of various c-type cytochromes implicates cytochrome c3 involvement (44) rather than hmc (6), cytochrome c553 (59), or cytochrome c7 (53). Additional evidence that the spectrum is not due to the hmc is provided by the observation that the hmc-deficient mutant showed a cytochrome spectrum similar to that of the wild type. Our metal-dependent spectra provided further evidence that cytochrome c3 is intimately involved in U(VI) (27) and Fe(III) (22) reduction. This cytochrome was also implicated in O2 reduction in sulfate-reducing bacteria (11, 12) where sulfidogenesis was interrupted during the time that O2 was being reduced (28). Our results are similar in that Fe(III) and U(VI) must be reduced before sulfate reduction will occur. Thus, it could be suggested that the periplasmic cytochrome c3 functions in a protective role (9) whereby oxidized compounds with higher redox potentials than that of sulfate (−220 mV) are immediately reduced to prevent cell oxidation. This could imply that electron transfer to the cytochrome is a dead-end pathway in the absence of alternate electron acceptors but, since it plays an essential role in pyruvate and sulfate reduction (45), its function as a central electron reservoir (13, 33) is more likely. Consistent with a central role for cytochrome c3, we found that the pyruvate- or lactate-reduced c-type cytochrome is oxidized by Fe(III), U(VI), and sulfate, suggesting a common pathway for metal and sulfate reduction from organic electron donors. However, the use of H2 as an electron donor showed that Fe(III) still inhibited U(VI) reduction, but sulfate loss was slowed instead of being halted by U(VI). These results suggest that cytochrome c3 may not be directly involved in H2-mediated sulfate reduction. The presence of a difference spectrum during H2-mediated Fe(III) or U(VI) reduction suggests that some electrons from H2 are used to reduce a c-type cytochrome, presumably cytochrome c3. The fact that no spectrum was observed during H2-mediated sulfate reduction but was present after the addition of a metal provides additional evidence that sulfate reduction from H2 does not involve this cytochrome. It could be argued that the difference spectrum was produced by oxidation of cytochrome c3 to a steady-state redox potential and that the H2 and sulfate redox state was more reduced than the H2 and U(VI) or Fe(III) state. We believe that this explanation is unlikely, as a spectrum was observed after oxidizing lactate-reduced cells with sulfate.

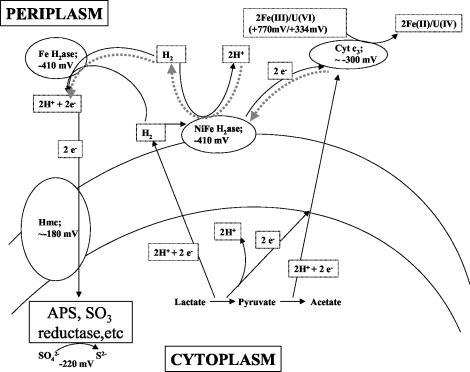

Hence, given the reports cited along with the present results, we propose the pathway shown in Fig. 5. D. vulgaris contains several periplasmic hydrogenases (Fe-only, NiFe, and NiFeSe) that could be involved in H2 oxidation (60). To account for the lack of c-type cytochrome spectrum during H2-mediated sulfate reduction, electrons from the Fe-only hydrogenase are likely donated to the hmc complex without cytochrome c3 participation. Further evidence for this pathway is the suppression of H2-mediated, but not lactate- or pyruvate-mediated, sulfate reduction with either the hyd (Fe-only hydrogenase mutant) or hmc mutants. As metal reduction rates from H2 are increased in the hyd mutant, it is likely that electrons needed for H2-mediated Fe(III) or U(VI) reduction could be supplied through an alternative enzyme, such as one of the NiFe hydrogenases (13, 33). This interpretation is consistent with the reported decreased ability of the hyd and hmc mutants to carry out H2-mediated sulfate reduction (14, 42, 60).

FIG. 5.

Proposed model for the electron transfer pathways for sulfate reduction from H2 versus that from lactate and pyruvate. Solid black lines represent currently proposed electron flow. Grey broken lines indicate the formation of H2 from lactate or pyruvate via cytochrome c3 and NiFe hydrogenase. H2ase = hydrogenase; hmc = high-molecular-weight complex.

Given the poor growth of the cytochrome c3 mutant with pyruvate, but not lactate or H2, as the electron donor (45), its reduced U(VI) reduction activity with pyruvate and H2 as electron donors (39), and our competition and spectral experiments, we can say that cytochrome c3 likely acts as an electron carrier for pyruvate oxidation. In our model, pyruvate oxidation indirectly produces H2 (60), and this may occur via electron transfer through cytochrome c3 to the NiFe hydrogenase, which is reversible in other bacteria (16), or by other mechanisms (60).

Electron flow from lactate oxidation also results in H2 production (42), but it does not always involve cytochrome c3, since its deletion had no effect on growth or sulfate reduction in the presence of lactate (45). However, Fe(III) and U(VI) inhibited lactate-mediated sulfate reduction in our assays, and cytochrome c3 reduced with lactate was oxidized with Fe(III), U(VI), and sulfate. Hence, we propose that electrons derived from lactate oxidation may flow through two or more pathways, one of which involves cytochrome c3 (42).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Natural and Accelerated Bioremediation Research Program of the Office of Biological and Environmental Research of the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

We thank Gerrit Voordow and Judy Wall for providing mutant strains and for their critiques of the manuscript and Matthew Ramsey for helpful discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aubert, C., G. Leroy, M. Bruschi, J. Wall, and A. Dolla. 1997. A single mutation in the heme 4 environment of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans Norway cytochrome c3 (Mr 26,000) greatly affects the molecular reactivity. J. Biol. Chem. 272:15128-15134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badziong, W., and R. K. Thauer. 1980. Vectorial electron transport in Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Marburg) growing on hydrogen plus sulfate as sole energy source. Arch. Microbiol. 125:167-174. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balch, W. E., and R. S. Wolfe. 1976. New approach to the cultivation of methanogenic bacteria: 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid (HS-CoM)-dependent growth of Methanobacterium ruminantium in a pressurized atmosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 32:781-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brina, R., and A. G. Miller. 1992. Direct detection of trace levels of uranium by laser-induced kinetic phosphorimetry. Anal. Chem. 64:1413-1418. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugna, M., M. T. Giudici-Orticoni, S. Spinelli, K. Brown, and M. Tegoni. 1998. Kinetics and interaction studies between cytochrome c3 and Fe-only hydrogenase from Delsulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 33:590-600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruschi, M., P. Bertrand, C. More, G. Leroy, J. Bonicel, J. Haladjian, G. Chottard, W. B. R. Pollock, and G. Voordouw. 1992. Biochemical and spectroscopic characterization of the high molecular weight cytochrome c from Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough expressed in Desulfovibrio desulfuricans G200. Biochemistry 31:3281-3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruschi, M., M. Loutfi, P. Bianco, and J. Haladjian. 1984. Correlation studies between structural and redox properties of cytochromes c3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 120:384-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cline, J. D. 1969. Spectrophotometric determination of hydrogen sulfide in natural waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 14:454-458. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cypionka, H. 2000. Oxygen respiration by Desulfovibrio species. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:827-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels, L., and D. Wessels. 1984. A method for the spectrophotometric assay of anaerobic enzymes. Anal. Biochem. 141:232-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dannenberg, S., M. Kroder, W. Dilling, and H. Cypionka. 1992. Oxidation of H2, organic compounds and inorganic sulfur compounds coupled to reduction of O2 or nitrate by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 158:93-99. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dilling, W., and H. Cypionka. 1990. Aerobic respiration in sulfate-reducing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 71:123-128. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolla, A., and M. Bruschi. 1988. The cytochrome c3-ferrodoxin electron transfer complex: cross-linking studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 932:26-32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolla, A., B. K. J. Pohorelic, J. K. Voordouw, and G. Voordouw. 2000. Deletion of the hmc operon of Desulfovibrio vulgaris subsp. vulgaris Hildenborough hampers hydrogen metabolism and low-redox-potential niche establishment. Arch. Microbiol. 174:143-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higuchi, Y., M. Kusunoki, Y. Matsuura, N. Yasuoka, and M. Kakudo. 1984. Refined structure of cytochrome c3 at 1.8 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 172:109-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kentemich, T., M. Bahnweg, F. Mayer, and H. Bothe. 1989. Localization of the reversible hydrogenase in cyanobacteria. Zeitschr. Naturforsch. C 44:384-391. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keon, R. G., F. Rongdian, and G. Voordouw. 1997. Deletion of the two downstream genes alters expression of the hmc operon of Desulfovibrio vulgaris subsp. vulgaris Hildenborough. Arch. Microbiol. 167:376-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemos, R. S., C. M. Gomes, M. Santana, J. LeGall, A. V. Xavier, and M. Teixeira. 2001. The “strict” anaerobe Desulfovibrio gigas contains a membrane-bound oxygen-reducing respiratory chain. FEBS Lett. 496:40-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim, S. K., D. H. Park, Y. K. Park, and B. H. Kim. 2001. Cloning, sequencing and functional expression in Escherichia coli of dmc gene encoding periplasmic tetraheme cytochrome c3 from Desulphovibrio desulphuricans M6. Anaerobe 7:263-269. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, C., S. Kota, J. M. Zachara, J. K. Fredrickson, and C. K. Brinkman. 2001. Kinetic analysis of the bacterial reduction of goethite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35:2482-2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, C., J. M. Zachara, Y. A. Gorby, J. E. Szecsody, and C. F. Brown. 2001. Microbial reduction of Fe(III) and sorption/precipitation of Fe(II) on Shewanella putrefaciens strain CN32. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35:1385-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovley, D. R., and E. J. P. Phillips. 1992. Bioremediation of uranium contamination with enzymatic uranium reduction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 26:2228-2234. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovley, D. R., and E. J. P. Phillips. 1987. Rapid assay for microbially reducible ferric iron in aquatic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:1536-1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovley, D. R., and E. J. P. Phillips. 1994. Reduction of chromate by Desulfovibrio vulgaris and its c3 cytochrome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:726-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovley, D. R., and E. J. P. Phillips. 1992. Reduction of uranium by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:850-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovley, D. R., E. E. Roden, E. J. P. Phillips, and J. C. Woodward. 1993. Enzymatic iron and uranium reduction by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Mar. Geol. 113:41-53. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lovley, D. R., P. K. Widman, J. C. Woodward, and E. J. P. Phillips. 1993. Reduction of uranium by cytochrome c3 of Desulfovibrio vulgaris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3572-3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marschall, C., P. Frenzel, and H. Cypionka. 1993. Influence of oxygen on sulfate reduction and growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 159:168-173. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masau, R. J. Y., J. K. Oh, and I. Suzuki. 2001. Mechanism of oxidation of inorganic sulfur compounds by thiosulfate-grown Thiobacillus thiooxidans. Can. J. Microbiol. 47:348-358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKinley, J. P., J. M. Zachara, S. Smith, and G. D. Turner. 1995. The influence of uranyl hydrolysis and multiple site-binding reactions on adsorption of U(VI) to montmorillonite. Clays Clay Min. 43:586-598. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer, T. E., R. G. Bartsch, and M. D. Kamen. 1971. Cytochrome c3: a class of electron transfer heme proteins found in both photosynthetic and sulfate-reducing bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 245:453-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noguera, D. R., G. A. Brusseau, B. E. Rittmann, and D. A. Stahl. 1998. A unified model describing the role of hydrogen in the growth in Desulfovibrio vulgaris under different environmental conditions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 59:732-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odom, J. D., and H. D. Peck. 1984. Hydrogenase, electron transfer proteins, and energy coupling in the sulfate-reducing bacteria Desulfovibrio. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 38:551-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Odom, J. M., and H. D. Peck. 1981. Hydrogen cycling as a general mechanism for energy coupling in the sulfate-reducing bacteria, Desulfovibrio sp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 12:47-50. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Odom, J. M., and J. D. Wall. 1987. Properties of a hydrogen-inhibited mutant of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ATCC 27774. J. Bacteriol. 169:1335-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oremland, R. S., and D. G. Capone. 1988. Use of “specific” inhibitors in biogeochemistry and microbial ecology. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 10:285-383. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pankhania, I. P., L. A. Gow, and W. A. Hamilton. 1986. The effect of hydrogen on the growth of Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough) on lactate. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:3549-3556. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pankhania, I. P., A. M. Spormann, W. A. Hamilton, and R. K. Thauer. 1988. Lactate conversion to acetate, CO2, and H2 in cell suspensions of Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Marburg): indications for the involvement of an energy driven reaction. Arch. Microbiol. 150:26-31. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payne, R. B., D. M. Gentry, B. J. Rapp-Giles, L. Casalot, and J. D. Wall. 2002. Uranium reduction by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans strain G20 and a cytochrome c3 mutant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3129-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pierrot, M., R. Haser, M. Frey, F. Payan, and J. Astier. 1982. Crystal structure and electron transfer properties of cytochrome c3. J. Biol. Chem. 257:14341-14348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pietzsch, K., B. C. Hard, and W. Babel. 1999. A Desulfovibrio sp. capable of growing by reducing U(VI). J. Basic Microbiol. 39:365-372. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pohorelic, B. K. J., J. K. Voordoouw, E. Lojou, A. Dolla, J. Harder, and G. Voordouw. 2002. Effects of deletion of genes encoding Fe-only hydrogenase of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough on hydrogen and lactate metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 184:679-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pollock, W. B. R., M. Loutfi, M. Bruschi, B. J. Rapp-Giles, J. D. Wall, and G. Voordouw. 1991. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the gene encoding the high-molecular-weight cytochrome c from Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J. Bacteriol. 173:220-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Postgate, J. R. 1956. Cytochrome c3 and desulphoviridin: pigments of the anaerobe Desulphovibrio desulphuricans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 14:545-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rapp-Giles, B. J., L. Casalot, R. S. English, J. A. Ringbauer, Jr., A. Dolla, and J. D. Wall. 2000. Cytochrome c3 mutants in Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:671-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schnell, F. D. (ed.). 1978. Photometric and fluorometric methods of analysis, p. 1351-1416. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 47.Segel, I. H. 1975. Enzyme kinetics: behavior and analysis of rapid equilibrium and steady state enzyme systems. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 48.Senko, J. M., J. D. Istok, J. M. Suflita, and L. R. Krumholz. 2002. In situ evidence for uranium immobilization and remobilization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:1491-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spear, J. R., L. A. Figueroa, and B. D. Honeyman. 2000. Modeling reduction of uranium(VI) under variable sulfate concentrations by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3711-3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spear, J. R., L. A. Figueroa, and B. D. Honeyman. 1999. Modeling the removal of uranium(VI) from aqueous solutions in the presence of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33:2667-2675. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steger, J. L., C. Vincent, J. D. Ballard, and L. R. Krumholz. 2002. Desulfovibrio sp. genes involved in the respiration of sulfate during metabolism of hydrogen and lactate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1932-1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steuber, J., H. Cypionka, and P. M. H. Kroneck. 1994. Mechanism of dissimilatory sulfite reduction by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans: purification of a membrane-bound sulfite reductase and coupling with cytochrome c3 and hydrogenase. Arch. Microbiol. 162:255-260. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan, J., and J. A. Cowan. 1990. Coordination and redox properties of a triheme cytochrome from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough). Biochemistry 29:4886-4892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tebo, B. M., and A. Y. Obraztsova. 1998. Sulfate-reducing bacterium grows with Cr(VI), U(VI), Mn(IV), and Fe(III) as electron acceptors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 162:193-198. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thony-Meyer, L. 1997. Biogenesis of respiratory cytochromes in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:337-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tucker, M. D., L. L. Barton, and B. M. Thomson. 1996. Kinetic coefficients for simultaneous reduction of sulfate and uranium by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 46:74-77. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ulrich, G. A., L. R. Krumholz, and J. M. Suflita. 1997. A rapid and simple method for estimating sulfate reduction activity and quantifying inorganic sulfides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1627-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valente, F. M. A., L. M. Saraiva, J. LeGall, A. V. Xavier, M. Teixeira, and I. A. C. Pereira. 2001. A membrane-bound cytochrome c3: a type II cytochrome c3 from Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Chembiochem. 2:895-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Verhagen, M. F. J. M., R. B. G. Wolbert, and W. R. Hagen. 1994. Cytochrome c553 from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough): electrochemical properties and electron transfer with hydrogenase. Eur. J. Biochem. 221:821-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Voordouw, G. 2002. Carbon monoxide cycling by Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J. Bacteriol. 184:5903-5911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Voordouw, G., and S. Brenner. 1986. Cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding cytochrome c3 from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough). Eur. J. Biochem. 159:347-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voordouw, G., B. R. Pollock, M. Bruschi, F. Guerlesquin, B. J. Rapp-Giles, and J. D. Wall. 1990. Functional expression of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough cytochrome c3 in Desulfovibrio desulfuricans G200 after conjugational gene transfer from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172:6122-6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong, D., Z. Lin, D. F. Juck, K. A. Terrick, and R. Sparling. 1994. Electron transfer reactions for the reduction of NADP+ in Methanosphaera stadtmanae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 120:285-290. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zellner, G., F. Neudorfer, and H. Diekmann. 1994. Degradation of lactate by an anaerobic mixed culture in a fluidized-bed reactor. Water Res. 28:1337-1340. [Google Scholar]