Abstract

Cholinergic systems are critical to the neural mechanisms mediating learning. Reduced nicotinic cholinergic receptor (nAChR) binding is a hallmark of normal aging. These reductions are markedly more severe in some dementias, such as Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacological central nervous system therapies are a means to ameliorate the cognitive deficits associated with normal aging and aging-related dementias. Trace eyeblink conditioning (EBC), a hippocampus- and forebrain-dependent learning paradigm, is impaired in both aged rabbits and aged humans, attributable in part to cholinergic dysfunction. In the present study, we examined the effects of galantamine (3 mg/kg), a cholinesterase inhibitor and nAChR allosteric potentiating ligand, on the acquisition of trace EBC in aged (30–33 months) and young (2–3 months) female rabbits. Trace EBC involves the association of a conditioned stimulus (CS) with an unconditioned stimulus (US), separated by a stimulus-free trace interval. Repeated CS–US pairings results in the development of the conditioned eyeblink response (CR) prior to US onset. Aged rabbits receiving daily injections of galantamine (Aged/Gal) exhibited significant improvements compared with age-matched controls in trials to eight CRs in 10 trial block criterion (P = 0.0402) as well as performance across 20 d of training [F(1,21) = 5.114, P = 0.0345]. Mean onset and peak latency of CRs exhibited by Aged/Gal rabbits also differed significantly [F(1,21) = 6.120/6.582, P = 0.0220/0.0180, respectively] compared with age-matched controls, resembling more closely CR timing of young drug and control rabbits. Galantamine did not improve acquisition rates in young rabbits compared with age-matched controls. These data indicate that by enhancing nicotinic and muscarinic transmission, galantamine is effective in offsetting the learning deficits associated with decreased cholinergic transmission in the aging brain.

Experimental evidence indicates that cognitive impairments observed during normal aging, as well as those attributable to aging-related dementias, are often associated with functional abnormalities in the cholinergic system (Bartus et al. 1982; Coyle et al. 1982, 1983; Hagan and Morris 1988; Solomon et al. 1990). The basal forebrain cholinergic (BFC) system is particularly vulnerable during aging (Yufu et al. 1994; Smith and Booze 1995). One structure adversely affected by the loss of BFC system integrity is the hippocampus (De Lacalle et al. 1994). Cognitive deficits associated with impaired cholinergic transmission are often observed in tasks dependent upon the hippocampus. The hippocampus has also been demonstrated as a site of pathology in clinical and animal studies of aging-related memory impairments (Solomon et al. 1988; Van Hoesen and Solodkin 1994; Geinisman et al. 1995). Therefore, hippocampus-dependent learning and memory tasks are valuable when assessing the potential therapeutic benefits of modulators of cholinergic system function. One such task is trace eyeblink conditioning (EBC).

EBC (Gormezano et al. 1962) is an associative learning paradigm in which a neutral tone conditioned stimulus (CS) is paired with a behaviorally salient corneal air-puff unconditioned stimulus (US). After repeated pairings, presentation of the CS elicits a conditioned response (CR) prior to onset of the US. During delay EBC, the tone CS precedes, overlaps, and coterminates with the air-puff US. Acquisition of delay conditioning is mediated by neural circuitry of the brainstem and cerebellum (Clark et al. 1984; Mauk and Thompson 1987). During trace EBC, the tone CS is separated temporally from the air-puff US by a stimulus-free trace interval. Acquisition of trace EBC is dependent upon the hippocampus (Solomon et al. 1986; Moyer Jr. et al. 1990; Kim et al. 1995; Weiss et al. 1999) and the caudal anterior cingulate cortex (Kronforst-Collins and Disterhoft 1998; Weible et al. 2000), in addition to the circuitry of the brainstem and cerebellum. Aged rats, rabbits, and humans show impairments in trace EBC (Thompson et al. 1996; Knuttinen et al. 2001a,b; McEchron et al. 2001). Age-related impairments in trace EBC range from mild to severe and are associated with distinct electrophysiological and morphological changes in hippocampal neurons (Geinisman et al. 1995; Thompson et al. 1996; Moyer Jr. et al. 2000; McEchron et al. 2001).

In the present study, we were interested in studying the effects of the cholinesterase inhibitor and cholinergic allosteric potentiating ligand (APL) galantamine on the acquisition of trace EBC in both aged and young rabbits. Galantamine functions in two ways. First, as a cholinesterase inhibitor, galantamine slows the breakdown of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft following vesicle release, increasing the effective strength of endogenous acetylcholine (Bores et al. 1996). Second, as an APL, galantamine increases the probability of channel opening induced by acetylcholine and nicotinic receptor agonists (Schrattenholz et al. 1996; Samochocki et al. 2000, 2003). The binding sites of APLs are distinct from those of agonists and antagonists. Therefore, they do not induce compensatory mechanisms seen with agonists and antagonists because they are not directly involved in the neurotransmission process (Maelicke et al. 2001; Woodruff-Pak et al. 2001). The goal of the present study was to determine whether galantamine facilitates acquisition of trace EBC. By incorporating both young and aged rabbits, the study was designed to test whether that facilitation was evident across age groups or was specific to an older population and, therefore, reflected an amelioration of age-related dysfunction of the cholinergic system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The subjects in the present study were 42young (2.0–3.0 months; 1.9 kg ± 0.36 SD) and 48 aged (30–33 months; 3.93 kg ± 0.42 SD) female New Zealand White albino rabbits. Aged rabbits were retired breeders. All rabbits were specific pathogen free, obtained from Covance Laboratories (Denver, PA). The rabbits were housed individually, with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, and maintained in accordance with the policies of Northwestern University's Animal Care and Use Committee.

Young and aged rabbits were organized according to training protocol (trace conditioning versus pseudoconditioning) and treatment group (galantamine versus saline), for a total of four training groups for each age group.

Surgical Protocol

Surgeries were performed by using sterile procedures. Ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) were administered intramuscularly to anesthetize rabbits prior to surgery. Eyes were kept moist with a thin layer of antibacterial ophthalmic ointment. Following surgical preparation, an incision was made in the scalp and the skull exposed. Six self-tapping screws were inserted into the skull to a depth of ∼2mm to anchor a lightweight headbolt assembly consisting of four nylon bolts. Dental cement was then used to cement the headbolt assembly in place. Rabbits were administered Buprenex (0.3 mg/kg, subcutaneously) to minimize postsurgical discomfort.

Drug Treatment and Training

Galantamine was obtained from Janssen Pharmaceutical. A fresh stock of galantamine was prepared each week. Behavioral training was performed by individuals blinded to the drug treatment.

One day after surgery, rabbits began 10 d of pretreatment, involving once daily subcutaneous injections of either galantamine (3 mg/kg) or saline (0.25 mL/kg). Pretreatment was carried out to avoid the possible incidence of behavioral side effects attributable specifically to initial exposure to the drug. Pretreatment was intended in part to increase the likelihood that any observed benefits afforded by galantamine were attributable to a stable modified biological baseline rather than an initial transient response to the drug. Our previous experience with the cholinesterase inhibitor metrifonate revealed that amelioration of age-related learning deficit was achieved by a steady-state cholinesterase inhibition with pretreatment (Kronforst-Collins et al. 1997b).

On the 10th day of pretreatment, all rabbits received a single acclimation session. During acclimation and subsequent training sessions, rabbits were restrained up to the neck by using a cloth bag and Plexiglas restrainer, from which the head was allowed to protrude. The lids of the right eye were held open with a Velcro strap and two small stainless steel dress hooks. A lightweight aluminum assembly secured an infrared sensor and air-puff delivery tube to the head bolt for the duration of each training session.

Following the 10th day of pretreatment, rabbits began daily sessions of either trace conditioning or pseudoconditioning. Computers running in-house custom-designed software controlled the delivery of all stimuli and acquired behavioral data (Akase et al. 1994). Each trace conditioning session consisted of 80 trials, with an average intertrial interval (ITI) of 45 sec. Each trial was 1750 msec in duration and consisted of a 500-msec pre-CS baseline interval, 250-msec CS and 150-msec US intervals separated by a 500-msec stimulus-free trace interval, and a 350-msec post-US interval. Pseudoconditioning sessions consisted of 80 tone alone and 80 airpuff alone trials, presented pseudorandomly, with a mean ITI of 22.5 sec. A binaural tone (6 kHz, 90 dB, 5 msec increase/decrease time) served as the CS, and an air-puff to the right eye (3.5 psi) served as the US. An infrared sensor suspended in front of the eye measured reflectance from the surface of the cornea. The computer recorded extension of the nictitating membrane across the surface of the cornea as an increase in signal voltage. This voltage was recorded by the computer at 1 kHz for a total of 1750 data points per trial.

Trace conditioning and pseudoconditioning sessions were 1 h in duration. Young and aged rabbits were paired together for training, with a new pair of rabbits beginning training each day. Young rabbits received 10 d of training. Aged rabbits received 20 d of training. Daily galantamine and saline injections were administered 1 to 3 h prior to each conditioning session throughout the course of training.

Acetylcholinesterase Analysis

To monitor the level of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity, blood was drawn from the marginal ear vein of each rabbit before pretreatment (baseline), following the first and 10th training sessions and, for the aged rabbits, following the 20th training session. Blood (400–500 μL) was collected in aliquots containing 50 μL of the anticoagulant heparin (Elkins-Sinn). Samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Blood plasma and red blood cells (RBCs) were separated and stored in a freezer (–80°C) for analysis following completion of behavioral training.

The cholinesterase inhibition analyses performed in the present study have been described in detail previously (Kronforst-Collins et al. 1997a). RBCs were diluted 1: 200 with Triton/EDTA. Testing was performed in a 5-min assay at 28°C on a substrate of tritiated AChE and cold AChE, at a final concentration of 500μM. Hemoglobin was determined by using a commercial kit (Sigma Chemical). AChE concentration in the RBCs was expressed as nmole/mg hemoglobin/min. ANOVAs were based on the percentage difference of AChE concentration between baseline and subsequent sample points for each animal. The data are illustrated as mean ±SEM. Measurements were made to identify changes in AChE levels following initial galantamine exposure and subsequent transition to steady-state levels, as any fluctuations specifically attributable to initial exposure effects diminished over time.

Behavioral Analysis

ANOVAs were performed to assess group and group × days differences for measures of mean percentage of CRs performed, as well as for mean CR area, amplitude, onset latency, and peak latency. Unpaired t-tests were performed to compare the number of trials required to reach a performance criterion of eight CRs in any 10-trial block on two consecutive days (eight of 10 CRs behavioral criterion). Only those CRs overlapping with the onset of the US, referred to as “adaptive” CRs because they reduced the impact of the US on the cornea, were included when measuring trials to eight CRs in a 10-trial block. The total number of training trials for each group (young, 800; aged, 1600) was used for rabbits failing to perform eight adaptive CRs in a 10-trial block. Unpaired t-tests were performed for final training day comparisons between young and aged groups. Following training, rabbits failing to exhibit a minimum 1-d percentage CR performance exceeding the performance of the corresponding aged-matched pseudoconditioned group performance were excluded from further analysis, as such levels of performance represented possible evidence of sensorimotor impairments.

RESULTS

Of the 90 rabbits originally included in the present study, 45 of 48 aged and 39 of 42young rabbits completed training (six were removed from the study due to health considerations). Twenty-three of 23 aged and 18 of 20 young trace-conditioned rabbits exceeded the performance of age- and treatment-matched pseudoconditioned controls, and are included in the subsequent analyses.

AChE Analysis

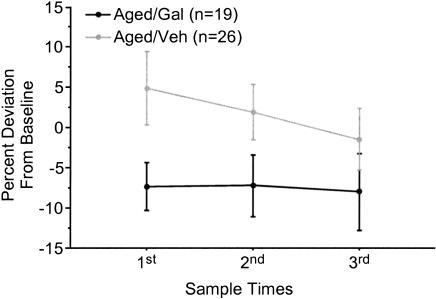

Two measurements were taken from each sample of RBCs to assess AChE levels. Analysis of AChE concentration in the blood indicated a significant inhibition of AChE in aged rabbits receiving daily injections of galantamine compared with that of aged control rabbits [F(1,66) = 4.062, P = 0.0479; Fig. 1]. The concentration of RBC AChE did not differ significantly across sample points for either the galantamine or saline group of aged rabbits. No significant difference in RBC AChE concentration was observed in young rabbits (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Percentage change in cholinesterase levels in red blood cells compared with baseline pretreatment levels for aged rabbits. Aged galantamine-administered (Aged/Gal) rabbits exhibited significantly reduced cholinesterase levels compared with aged saline-treated control (Aged/Veh) rabbits. Time points correspond to the first, tenth, and twentieth days of training. Aged/Gal and Aged/Veh groups include trace conditioned and pseudoconditioned rabbits.

Trace Conditioning

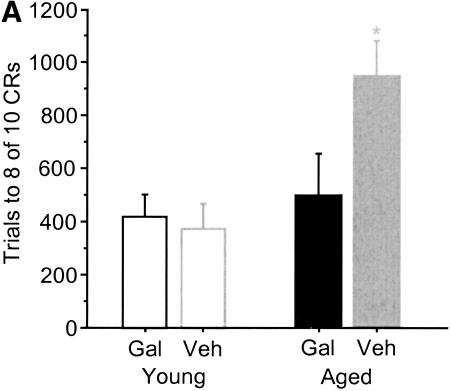

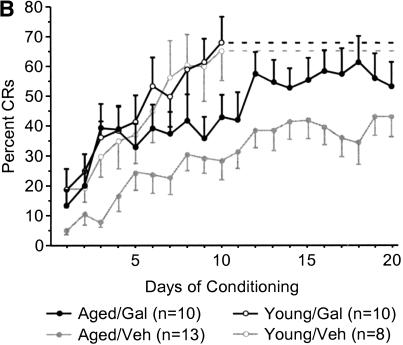

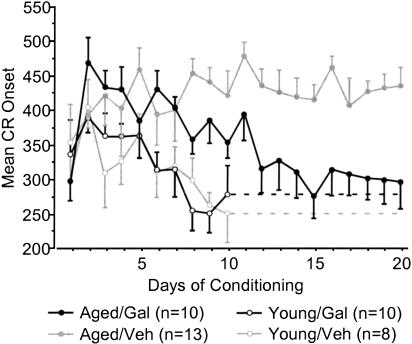

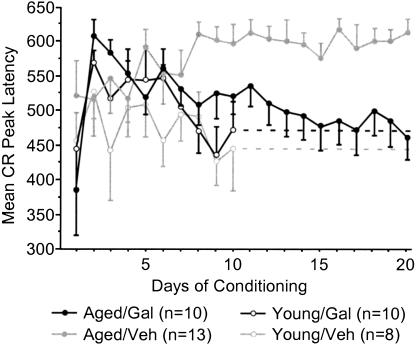

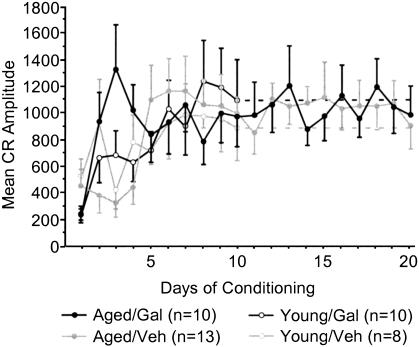

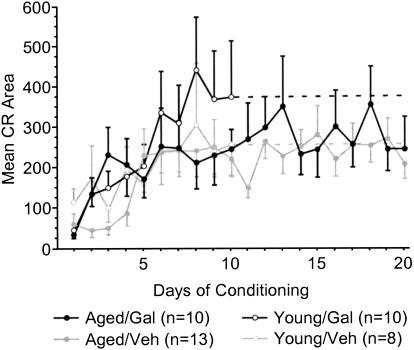

Aged galantamine-administered (Aged/Gal) rabbits achieved the eight of 10 CRs behavioral criterion more rapidly than did age-matched vehicle controls (Aged/Veh; t = –2.187, p = 0.0402; Fig. 2A). Aged/Gal rabbits achieved this behavioral criterion in 495 ± 158 trials (SE), with all 10 rabbits achieving criterion by the end of training. Mean trials to performance of the same criterion for Aged/Veh rabbits was 942 ± 132trials (SE), with three of 13 rabbits failing to achieve criterion by the completion of training. The improved performance of Aged/Gal rabbits was maintained across 20 d of trace conditioning [ANOVA: F(1,21) = 5.114, P = 0.0345; Fig. 2B]. ANOVAs also revealed a group and group × days effect for Aged/Gal rabbits compared with Aged/Veh rabbits over the course of training for measures of CR onset [F(1, 21/19, 399) = 6.120/2.658, P = 0.0220/0.0002, respectively] and CR peak latency [F(1, 21/19, 399) = 6.582/2.290, P = 0.0180/0.0017, respectively], indicating a shift in response timing compared to Aged/Veh rabbits (Figs. 3, 4, respectively). Measures of CR amplitude and area did not differ significantly between Aged/Gal and Aged/Veh rabbits (Figs. 5, 6, respectively).

Figure 2.

(A) Number of trials to performance of eight conditioned responses within a 10-trial block on two consecutive days of trace conditioning. Aged control (Veh) rabbits required significantly more trials to achieve this criterion compared with aged galantamine-administered (Gal) and young rabbits (*significant difference). (B) Mean percentage of conditioned responses for each day of trace conditioning. Aged galantamine-administered (Aged/Gal) rabbits performed significantly more conditioned responses over the course of training compared with aged saline control (Aged/Veh) rabbits. Aged/Gal and young rabbits did not differ significantly on the final day of training. No significant difference was observed between young galantamine-administered (Young/Gal) and young saline control (Young/Veh) rabbits.

Figure 3.

Mean conditioned response onset for each day of trace conditioning. Aged galantamine-administered (Aged/Gal) rabbits exhibited a significant change in onset timing across days, as well as significantly shorter mean onset time compared with aged saline control (Aged/Veh) rabbits. Aged/Gal and young rabbits did not differ significantly on the final day of training. No significant difference was observed between young galantamine-administered (Young/Gal) and young saline control (Young/Veh) rabbits.

Figure 4.

Mean conditioned response peak latency for each day of trace conditioning. Aged galantamine-administered (Aged/Gal) rabbits exhibited a significant change in peak latency timing across days, as well as significantly shorter mean peak latency time compared with aged saline control (Aged/Veh) rabbits. Aged/Gal and young rabbits did not differ significantly on the final day of training. No significant difference was observed between young galantamine-administered (Young/Gal) and young saline control (Young/Veh) rabbits.

Figure 5.

Mean conditioned response amplitude for each day of trace conditioning. No significant differences were observed within or between age groups over the course of training (Aged/Gal indicates aged galantamine-administered rabbits; Aged/Veh, aged saline control rabbits; Young/Gal, young galantamine-administered rabbits; and Young/Veh, young saline control rabbits).

Figure 6.

Mean conditioned response area for each day of trace conditioning. No significant differences were observed within or between age groups over the course of training (Aged/Gal indicates aged galantamine-administered rabbits; Aged/Veh, aged saline control rabbits; Young/Gal, young galantamine-administered rabbits; and Young/Veh, young saline control rabbits).

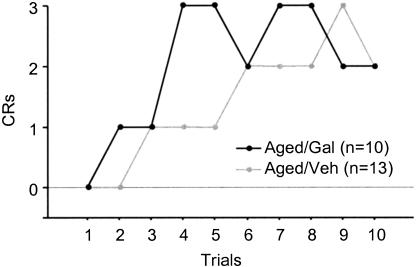

The differences in performance between Aged/Gal and Aged/Veh rabbits were apparent early in training. An unpaired t-test indicated that Aged/Gal rabbits performed significantly more CRs compared with that of Aged/Veh rabbits during the first training session [F(1,21) = 2.227, P = 0.0370]. However, as illustrated in Figure 7, there is a similarity of CR performance between groups during the first 10 trials. In addition, an unpaired t-test failed to identify a significant group difference during the first 20 trials. Thus, the data indicate that the difference in percentage CR performance between Aged/Gal and Aged/Veh rabbits developed over the course of the first day of training and is therefore likely to represent a learning-related performance difference and not simply an effect of galantamine on sensorimotor processing.

Figure 7.

Individual conditioned responses recorded for aged galantamine-administered (Aged/Gal) and aged saline control (Aged/Veh) rabbits over the first 10 training trials on the first day of trace conditioning.

Trials to the eight of 10 CRs behavioral criterion and CR performance across 10 d of training did not differ significantly between young galantamine-administered (Young/Gal) rabbits and age-matched vehicle controls (Young/Veh; Fig. 2A,B, respectively). In addition, measures of CR onset, peak latency, amplitude, and area did not differ significantly between groups (Figs. 3,4,5,6, respectively).

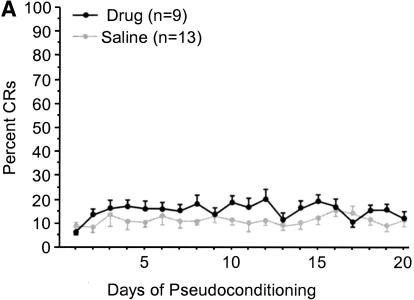

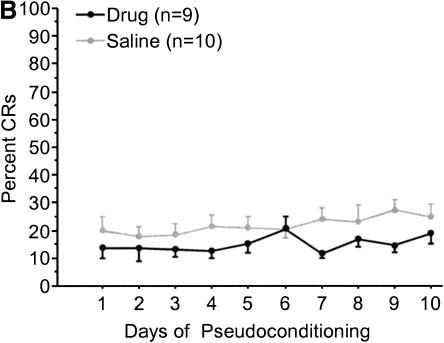

Pseudoconditioning

Galantamine administration did not result in a significant change in proportion of eyeblinks following tone presentation compared with that for age-matched controls in either age group (Fig. 8A,B). Measures of UR amplitude, area, onset, or peak latency did not differ significantly between drug and vehicle groups for either age group (data not shown). ANOVAs revealed a significant decrease in UR onset and peak latency over the course of training for young [F(9,153) = 10.669/2.172, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0269, respectively] and aged [F(19,380) = 3.943/2.411, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0009, respectively] rabbits, indicating a more rapid response to the presentation of the air-puff. No significant change in the UR amplitude or area were observed for either age group (data not shown).

Figure 8.

(A) Mean tone-CS-elicited eyeblink responses by day during pseudoconditioning of aged rabbits. No significant differences were observed between aged galantamine-administered (Aged/Gal) and aged saline control (Aged/Veh) rabbits. (B) Mean tone-CS-elicited eyeblink responses by day during pseudoconditioning of young rabbits. No significant differences were observed between young galantamine-administered (Young/Gal) and young saline control (Young/Veh) rabbits.

Aged Versus Young

The data indicate that the performance of Aged/Gal rabbits approaches that of Young/Gal and Young/Veh rabbits. Performance on the first day of conditioning did not differ significantly between Aged/Gal and Young/Gal or Young/Veh rabbits (see Fig. 2B). Trials of the eight of 10 CRs behavioral criterion did not differ significantly between Aged/Gal and Young/Gal or Young/Veh rabbits (Fig. 2A). No significant group effect in percent CR performance was detected between Aged/Gal and Young/Gal or Young/Veh rabbits for the first 10 d of training (Fig. 2B), although a significant group × days effect was detected between Aged/Gal and both Young/Gal [F(9,162) = 2.554, P = 0.009] and Young/Veh rabbits [F(9,144) = 2.673, P = 0.0067]. Onset latency of the CR differed significantly between Aged/Gal and both Young/Gal [F(1,18) = 7.941, P = 0.0114] and Young/Veh [F(1,16) = 5.826, P = 0.0281] rabbits, attributable to a decrease in CR onset exhibited earlier in training by both groups of young rabbits. However, no group × days effect was found for CR onset latency between the same groups (Figs. 3, 4), indicating a similar shift in onset latency over the course of training. No significant group or group × days differences were observed between Aged/Gal and Young/Gal or Young/Veh rabbits over the first 10 d of training for measures of CR peak latency, peak amplitude, or area. Unpaired t-tests revealed no significant group differences between Aged/Gal and Young/Gal or Young/Veh rabbits on the final day of training for percentage of CRs, CR onset, peak latency (see Figs. 2B, 3, 4 respectively) peak amplitude, or area (see Figs. 5, 6, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The goal of the present study was to examine the effects of the cholinesterase inhibitor and APL galantamine on acquisition of trace EBC by aged and young rabbits. The data indicate that the performance of Aged/Gal rabbits was significantly improved during trace EBC compared with that of Aged/Veh controls. This improvement is accompanied by a significant reduction in AChE levels compared with those of Aged/Veh rabbits that remained stable over the course of training. The absence of drug effects observed during pseudoconditioning indicates that these improvements were specific to the enhanced processing of associative information. No comparable differences were observed in the group of Young/Gal rabbits. The nature of the drug effects observed in the present study indicates that galantamine ameliorates some of the cognitive deficits associated with age-related dysfunction of the cholinergic system (Bartus et al. 1982; Coyle et al. 1982, 1983; Hagan and Morris 1988; Solomon et al. 1990) but is less effective at enhancing cognition in young rabbits at the dosages used here. The absence of a drug effect with the accompanying absence of detectable cholinesterase inhibition in young rabbits is discussed further below.

Aged/Gal rabbits performed a behavioral criterion of eight adaptive CRs in a 10-trial block on two consecutive days (eight of 10 CRs behavioral criterion) significantly earlier in training than did Aged/Veh rabbits (Fig. 2A). Aged/Gal rabbits also performed a significantly higher percentage of CRs across 20 d of training compared with Aged/Veh rabbits (Fig. 2B). Taken together, the data indicate that galantamine facilitates acquisition and overall performance of trace EBC by aged rabbits.

In contrast to the improved performance of Aged/Gal rabbits during trace EBC, galantamine produced no discernible behavioral effects on young rabbits for the measures examined in the present study. Interpretation of this negative result is complicated by the lack of detectable AChE inhibition in the plasma of Young/Gal rabbits compared with age-matched vehicle (Aged/Veh) controls. There are several points to consider in evaluating the effects of galantamine on cognition in young rabbits, based on the present data. First, the effects of several AChE inhibitors have been shown to vary with age. Specifically, AChE inhibition is greater in aged subjects compared with young subjects, as measured in brain or plasma, when using tacrine, donepezil, or galantamine (Kosasa et al. 1999; Woodruff-Pak et al. 2001). Second, galantamine produces relatively less AChE inhibition than do other cholinesterase inhibitors (Hallak and Giacobini 1987; Thomsen et al. 1991; Kronforst-Collins et al. 1997b). It is possible that the level of cholinesterase inhibition produced by galantamine was below a detectable threshold, at the dosage used, for young rabbits, as measured using RBCs. This hypothesis is supported by Woodruff-Pak et al. (2001) who demonstrated a facilitation by galantamine (3 mg/kg) on the acquisition of long-duration delay EBC in young rabbits, which correlated with decreased AChE levels in brain but not plasma. The rabbits used by Woodruff-Pak et al. (2001) are the same strain and sex as those used in the present study. Therefore, we hypothesize that had AChE assays in the present study been performed in brain rather than RBCs, a significant difference in cholinesterase levels between Young/Gal and Young/Veh would have been revealed.

The differences between the paradigms used by Woodruff-Pak et al. (2001) and our laboratory make a direct comparison of the behavioral data problematic. In the present study, the performance of Young/Gal and Young/Veh rabbits was comparable to that of the Young/Gal rabbits in the earlier study of Woodruff-Pak et al. (2001). Young/Gal and Young/Veh performed at levels comparable to those observed in previous studies from our laboratory (Thompson and Disterhoft 1997; Kronforst-Collins and Disterhoft 1998; Weible et al. 2000), indicating that such performance levels were not atypical for young rabbits. Several studies have demonstrated that additional higher-order neural structures in the rabbit are necessary for the acquisition of trace EBC that are not necessary for delay EBC (Solomon et al. 1986; Moyer Jr. et al. 1990; Kim et al. 1995; Kronforst-Collins and Disterhoft 1998), even with an interstimulus interval as long as that incorporated by Woodruff-Pak and colleagues (Weible et al. 2000). It is possible, therefore, that the facilitation observed by Woodruff-Pak et al. (2001) in Young/Gal rabbits was restricted to delay versions of the EBC paradigm. Taken together, the behavioral data indicate that, at the dosages used in the present study, the action of galantamine is insufficient to produce a significant improvement in the acquisition of trace EBC in young rabbits.

Pseudoconditioning

No drug effect was detected during pseudoconditioning for either age group. Galantamine administration did not alter the percentage of tone-evoked blink responses or the amplitude, area, onset, or peak latency of the UR, during pseudoconditioning of either young or aged rabbits (Fig. 8A,B). However, no drug-specific alterations of US were observed for either age group. The analyses of pseudoconditioning data indicate that the increased CR performance exhibited by Aged/Gal rabbits was associative in nature, rather than simply reflecting a drug-specific alteration of responses to conditioning stimuli used in the present study. Two observations support this assertion. First, significantly fewer trials were required by Aged/Gal rabbits to achieve the eight of 10 CRs behavioral criterion, indicating the increased incidence of appropriately timed conditioned responses. Second, behavioral responses to the CS gradually increased over the course of the first training session, rather than being present during initial training trials.

Aged/Young Comparisons

The performance of Aged/Gal rabbits was similar to that of Young/Gal and Young/Veh rabbits on a variety of the measures used in the present study. Despite a faster rate of acquisition by Young/Gal and Young/Veh rabbits during the first 10 training sessions, overall CR performance during the same period did not differ significantly between Aged/Gal and either group of young rabbits (Fig. 2B), and the mean percentage of CRs performed on the final day of training did not differ significantly between Aged/Gal and Young/Gal or Young/Veh rabbits. The number of trials to achieve the eight of 10 CRs behavioral criterion also did not differ significantly between Aged/Gal and Young/Gal or Young/Veh rabbits (Fig. 2A), indicating a similar rate of acquisition. Similarities were also evident between Aged/Gal and young rabbits regarding CR timing. After initial training sessions, Aged/Gal and young rabbits exhibited similar decreases in CR onset and peak latency, differing insignificantly on each groups' final day of training (Figs. 3, 4). The data indicate that galantamine may, at least in part, restore the development of properly timed CRs during trace EBC in aged rabbits.

Cholinergic Modulation and Learning

Considerable evidence exists that modulation of cholinergic transmission may be beneficial as a treatment for the cognitive deficits attributable to normal aging and aging-related dementia (Hallak and Giacobini 1987, 1989; Davis et al. 1992; Dawson and Iversen 1993). Inhibition of AChE has been demonstrated as one method of ameliorating aging-related cognitive deficits related to degraded cholinergic transmission in the central nervous system (Davis et al. 1992; Knapp et al. 1994; Levy et al. 1994). However, major differences with respect to efficacy and effective duration, as well as severity of side effects, between cholinesterase inhibitors have been reported (Hallak and Giacobini 1989; Sclar and Skaer 1992; Watkins et al. 1994). To function as an effective treatment for the cognitive deficits associated with cholinergic system dysfunction in the aging nervous system, a therapeutic agent must remain effective over an extended time frame at nontoxic dosages. Galantamine appears to be an example of such a therapeutic agent.

In the present study, galantamine was found to significantly improve the performance of aged rabbits during trace EBC and to significantly reduce the concentration of AChE in RBCs. There is evidence indicating a deficit in cholinergic synaptic transmission in the hippocampus during normal aging (Shen and Barnes 1996; Jouvenceau et al. 1997). This deficit is significant given the importance of the hippocampus during acquisition of trace EBC (Solomon et al. 1986; Moyer Jr. et al. 1990; Kim et al. 1995; Weiss et al. 2000), and the acquisition deficits and hippocampal dysfunction routinely observed with aged rabbits during trace conditioning (Thompson et al. 1996; Kronforst-Collins et al. 1997b; Thompson and Disterhoft 1997; Moyer Jr. et al. 2000; McEchron et al. 2001). These findings indicate that the improvements demonstrated by aged rabbits in the present study are, at least in part, attributable to improved cholinergic transmission in the hippocampus by galantamine.

Galantamine has previously been demonstrated to lessen the severity of cognitive deficits following damage to the cholinergic system. Treatment with galantamine reversed learning impairments in passive avoidance and Morris water maze tasks resulting from lesions of the nucleus basalis magnocellularis (Sweeney et al. 1988, 1990), and radial arm maze learning impaired by alcohol-induced cholinergic dysfunction (Iliev et al. 1999). Galantamine is proposed to function in two ways. First, as a cholinesterase inhibitor (Bores et al. 1996). Second, as an APL, increasing the probability of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) activation (Schrattenholz et al. 1996; Samochocki et al. 2000, 2003; Maelicke et al. 2001). The latter of these two functions, that of the APL, is accomplished at binding sites distinct for nAChR agonists and antagonists, eliminating the compensatory mechanisms associated with agonists and antagonists, extending the effective duration of the drug over time (Maelicke et al. 2001; Woodruff-Pak et al. 2001). The inhibition of AChE induced by galantamine in the present study is less than that observed by some other cholinesterase inhibitors (Hallak and Giacobini 1987; Kronforst-Collins et al. 1997b). It is possible that the magnitude of the difference in AChE concentration in the blood effected by galantamine would be more robust if measured directly in brain (Woodruff-Pak et al. 2001). However, the relatively modest levels of AChE inhibition observed in the present study also indicate the need for further study of the role of the APL in cognition, given the dual role reported for galantamine on modulation of the cholinergic system, and the possible role of the APL in the results presented here.

The data from the present study are similar to those previously described in a study investigating the therapeutic effects of the cholinesterase inhibitor metrifonate (Kronforst-Collins et al. 1997b). In that study, aged rabbits exhibited improved acquisition of trace EBC in a dose-dependent manner over the course of 25 training sessions. The rate of acquisition, as measured by the eight of 10 CRs behavioral criterion, was also significantly higher for all aged rabbits receiving the drug compared with age-matched vehicle controls. In a pair of subsequent studies, metrifonate application in vitro was found to increase the excitability of CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons by decreasing the Ca2+-mediated afterhyperpolarization (AHP) and spike accommodation (Oh et al. 1999; Power et al. 2001). Preliminary data on the effects of galantamine application in vitro indicate a similar reduction of the AHP and spike accommodation in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Oh et al. 2000). Reductions of the AHP and spike accommodation in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons are observed in young and aged rabbits that have successfully acquired trace EBC but are absent in trained rabbits that fail to learn (Moyer Jr. et al. 1996, 2000; Thompson et al. 1996). It has been similarly demonstrated in vivo that rabbits acquiring trace EBC exhibit a pattern of neuronal modulation in the hippocampus that is absent in nonlearners and pseudoconditioned animals (McEchron and Disterhoft 1997; McEchron et al. 2001; Munera et al. 2001). In addition to its effects as an AChE inhibitor, galantamine enhances synaptic transmission between CA3-CA1 synapses, supporting the proposed role of galantamine as an APL. Galantamine significantly enhances the excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) measured by Schaeffer collateral stimulation (Maelicke et al. 2001). Blockade of the enhanced EPSP was achieved with the nicotinic receptor antagonist, α-bungarotoxin, indicating a likely involvement of the α7 nAChRs in the phenomenon. nAChRs are capable of modulating neurotransmitter release throughout the brain (Wonnacott 1997; Lena et al. 1999; Barazangi and Role 2001; Dani 2001). For example, Gray et al. (1996) have demonstrated that activation of α7 nAChRs by nicotine or nicotinic agonists results in enhanced released of glutamate in the hippocampus. Taken together, the improved learning by aged rabbits imparted by galantamine likely reflects the combined influences of the drug as an AChE inhibitor as well as an APL. Further work will be necessary to determine how, and to what extent, each of these roles contributes to improved function of the aged central nervous system.

Summary

Galantamine, a cholinesterase inhibitor and APL, facilitates the acquisition of trace EBC in aged rabbits compared with age-matched controls. The data indicate that aged rabbits receiving daily injections of galantamine exhibited both an increase in percentage of CRs as well as a shift in CR timing similar to that observed in young rabbits. The changes in performance observed in Aged/Gal rabbits indicate that galantamine is ameliorating the cognitive deficits typically associated with cholinergic dysfunction commonly observed in the aging central nervous system, particularly the hippocampus, which is critical for the temporal encoding and consolidation of the conditioned reflex.

Acknowledgments

We thank Diana Giczewski, and Jayne Azzarello for technical assistance, and the laboratory of Dr. Robert T. Chatterton Jr., who performed the AChE analyses. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants F32(A.P.W.), F32NS41234 (M.M.O.), R37 AG08796 (J.F.D.), and Janssen Pharmaceutica L.P. (J.F.D.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.learnmem.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/lm.69804.

References

- Akase, E., Thompson, L.T., and Disterhoft, J.F. 1994. A system for quantitative analysis of associative learning, part 2: Real-time software for MS-DOS microcomputer. J. Neurosci. Methods 54: 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barazangi, N. and Role, L.W. 2001. Nictotine-induced enhancement of glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic transmission in the mouse amygdala. J. Neurophys. 86: 463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartus, R.T., Dean III, R.L., Beer, B., and Lippa, A.S. 1982. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science 217: 408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bores, G.M., Huger, F.P., Petko, W., Mutlib, A.E., Camacho, F., Rush, D.K., Selk, D.E., Wolf, V., Kosley Jr., R.W., Davis, L., et al. 1996. Pharmacological evaluation of novel Alzheimer's disease therapeutics: Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors related to galanthamine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 319: 728–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G.A., McCormick, D.A., Lavond, D.G., and Thompson, R.F. 1984. Effects of lesions of the cerebellar nuclei on conditioned behavioral and hippocampal neuronal responses. Brain Res. 291: 125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, J.T., Price, D.L., and DeLong, M.R. 1982. Brain mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease. Hosp. Pract. 17: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, J.T., Price, D.L., and DeLong, M.R. 1983. Alzheimer's disease: A disorder of cortical cholinergic innervation. Science 219: 1184–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani, J.A. 2001. Overview of nicotinic receptors and their roles in the central nervous system. Bio. Psych. 49: 166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.L., Thal, L.J., Gamzu, E.R., Davis, C.S., Woolson, R.F., Gracon, S.I., Drachman, D.A., Schneider, L.S., Whitehouse, P.J., and Hoover, T.M. 1992. A double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study of tacrine for Alzheimer's disease. New Engl. J. Med. 327: 1253–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, G.R. and Iversen, S.D. 1993. The effects of novel cholinesterase inhibitors and selective muscarinic receptor agonists in tests of reference and working memory. Behav. Brain Res. 57: 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lacalle, S., Lim, C., Sobreviela, T., Mufson, E.J., Hersh, L.B., and Saper, C.B. 1994. Cholinergic innervation in the human hippocampal formation including the entorhinal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 345: 321–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geinisman, Y., Detoledo-Morrell, L., Morrell, F., and Heller, R.E. 1995. Hippocampal markers of age-related memory dysfunction: Behavioral, eletrophysiological and morphological perspectives. Prog. Neurobiol. 45: 223–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormezano, I., Schneiderman, N., Deaux, E., and Fuentes, I. 1962. Nictitating membrane: Classical conditioning and extinction in the albino rabbit. Science 138: 33–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, R., Rajan, A.S., Radcliffe, K.A., Yakehiro, M., and Dani, J.A. 1996. Hippocampal synaptic transmission enhanced by low concentrations of nicotine. Nature 383: 713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, J.J. and Morris, R.G.M. 1988. The cholinergic hypothesis of memory: A review of animal experiments. In Psychopharmacology of the aging nervous system: Handbook of psychopharmacology (eds. L.L. Iversen, et al.), pp. 237–323. Plenum Press, New York.

- Hallak, M. and Giacobini, E. 1987. A comparison of the effects of two inhibitors on brain cholinesterase. Neuropharmacology 26: 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallak, M. and Giacobini, E. 1989. Physostigmine, tacrine, and metrifonate: The effect of multiple doses on acetylcholine metabolism in rat brain. Neuropharmacology 28: 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliev, A., Traykov, V., Prodanov, D., Mantchev, G., Yakimova, K., Krushkov, I., and Boyadjieva, N. 1999. Effect of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor galanthamine on learning and memory in prolonged alcohol intake rat model of acetylcholine deficit. Methods Findings Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 21: 297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouvenceau, A., Billard, J.M., Lamour, Y., and Dutar, P. 1997. Potentiation of glutamatergic EPSPs in rat CA1 hippocampal neurons after selective cholinergic denervation by 192IgG-saporin. Synapse 26: 292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.J., Clark, R.E., and Thompson, R.F. 1995. Hippocampectomy impairs the memory of recently, but not remotely, acquired trace eye-blink conditioned responses. Behav. Neurosci. 109: 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, M.J., Knopman, D.S., Solomon, P.R., Pendlebury, W.W., Davis, C.S., and Gracon, S.I. 1994. A 30-week randomized controlled trial of high-dose tacrine in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Tacrine Study Group. JAMA 271: 985–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuttinen, M.-G., Gamelli, A.E., Weiss, C., Power, J.M., and Disterhoft, J.F. 2001a. Age-related effects on eyeblink conditioning in the F344 X BN F1 hybrid rat. Neurobiol. Aging 22: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuttinen, M.-G., Power, J.M., Preston, A.R., and Disterhoft, J.F. 2001b. Awareness in classical differential eyeblink conditioning in young and aging humans. Behav. Neurosci. 115: 747–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosasa, T., Kuriya, Y., Matsui, K., and Yamanishi, Y. 1999. Inhibitory effects of donepezil hydrochloride (E2020) on cholinesterase activity in brain and peripheral tissues of young and aged rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 386: 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronforst-Collins, M.A. and Disterhoft, J.F. 1998. Lesions of the caudal area of rabbit medial prefrontal cortex impair trace eye-blink conditioning. Neurobiol. Learning Mem. 69: 147–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronforst-Collins, M.A., Moriearty, P.L., Ralph, M., Becker, R.E., Schmidt, B., Thompson, L.T., and Disterhoft, J.F. 1997a. Metrifonate treatment enhances acquisition of eyeblink conditioning in aging rabbits. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 56: 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronforst-Collins, M.A., Moriearty, P.L., Schmidt, B., and Disterhoft, J.F. 1997b. Metrifonate improves associative learning and retention in aging rabbits. Behav. Neural. 111: 1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lena, C., de Kerchove d'Exaerde, A., Cordero-Erausquin, M., Le Novere, N., del Mar Arroy-Jimenez, M., and Changeux, J.P. 1999. Diversity and distribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the locus ceruleus neurons. PNAS USA 96: 12126–12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S., Brandeis, R., Treves, T.A., Meshulam, Y., Mwassi, R., Reiler, D., Wengier, A., Glikfeld, P., Grunwald, J., and Dachir, S. 1994. Transdermal physostigmine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer Dis. Associated Disorders 8: 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maelicke, A., Samochocki, M., Jostock, R., Fehrenbacher, A., Ludwig, J., Albuquerque, E.X., and Zerlin, M. 2001. Allosteric sensitization of nicotinic receptors by galantamine: A new treatment strategy for Alzheimer's disease. Biol. Psych. 49: 279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauk, M.D. and Thompson, R.F. 1987. Retention of classically conditioned eyelid responses following acute decerebration. Brain Res. 403: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEchron, M.D. and Disterhoft, J.F. 1997. Sequence of single neuron changes in CA1 hippocampus of rabbits during acquisition of trace eyeblink conditioned responses. J. Neurophysiol. 78: 1030–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEchron, M.D., Weible, A.P., and Disterhoft, J.F. 2001. Aging and learning-specific changes in single-neuron activity in CA1 hippocampus during rabbit trace eyeblink conditioning. J. Neurophysiol. 86: 1839–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer Jr., J.R., Deyo, R.A., and Disterhoft, J.F. 1990. Hippocampectomy disrupts trace eye-blink conditioning in rabbits. Behav. Neurosci. 104: 243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer Jr., J.R., Thompson, L.T., and Disterhoft, J.F. 1996. Acquisition of trace eye-blink conditioning transiently increases rabbit CA1 pyramidal cell excitability: Implications for hippocampal plasticity during memory consolidation. J. Neurosci. 16: 5536–5546.8757265 [Google Scholar]

- Moyer Jr., J.R., Power, J.M., Thompson, L.T., and Disterhoft, J.F. 2000. Increased excitability of aged rabbit CA1 neurons after trace eyeblink conditioning. J. Neurosci. 20: 5476–5482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munera, A., Gruart, A., Munoz, M.D., Fernandez-Mas, R., and Delgado-Garcia, J.M. 2001. Hippocampal pyramidal cell activity encodes conditioned stimulus predictive value during classical conditioning in alert cats. J. Neurophysiol. 86: 2571–2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, M.M., Power, J.M., Thompson, L.T., Moriearty, P.L., and Disterhoft, J.F. 1999. Metrifonate increases neuronal excitability in CA1 pyramidal neurons from both young and aging rabbit hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 19: 1814–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, M.M., Wu, W.W., Vogel, R.W., Woodruff-Pak, D.S., and Disterhoft, J.F. 2000. Galanthamine enhances CA1 neuronal excitability and facilitates learning in young & aging rabbits. Soc. Neurosci. Abs. 26: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Power, J.M., Oh, M.M., and Disterhoft, J.F. 2001. Metrifonate decreases sIAHP in CA1 pyramidal neurons in vitro. J. Neurophysiol. 85: 319–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samochocki, M., Zerlin, M., Jostock, R., Groot Kormelink, P.J., Luyten, W.H., Albuquerque, E.X., and Maelicke, A. 2000. Galantamine is an allosterically potentiating ligand of the human α4/β 2nAChR. Acta. Neurol. Scand. 176: 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samochocki, M., Hoffle, A., Fehrenbacher, A., Jostock, R., Ludwig, J., Christner, C., Radina, M., Zerlin, M., Ullmer, C., Pereira, E.F., et al. 2003. Galantamine is an allosterically potentiating ligand of neuronal nicotinic but not of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 305: 1024–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrattenholz, A., Pereira, E.F., Roth, U., Weber, K.H., Albuquerque, E.X., and Maelicke, S. 1996. Agonist responses of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are potentiated by a novel class of allosterically acting ligands. Mol. Pharmacol. 49: 1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclar, D.A. and Skaer, T.L. 1992. Current concepts in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Clin. Ther. 14: 2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J. and Barnes, C.A. 1996. Age-related decrease in cholinergic synaptic transmission in three hippocampal subfields. Neurobiol. Aging 17: 439–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.L. and Booze, R.M. 1995. Cholinergic and GABAergic neurons in the nucleus basalis region of young and aged rats. Neuroscience 67: 679–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, P.R., Vander Schaaf, E.R., Thompson, R.F., and Weisz, D.J. 1986. Hippocampus and trace conditioning of the rabbit's classically conditioned nictitating membrane response. Behav. Neurosci. 100: 729–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, P.R., Beal, M.F., and Pendlebury, W.W. 1988. Age-related disruption of classical conditioning: A model systems approach to memory disorders. Neurobiol. Aging 9: 535–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, P.R., Groccia-Ellison, M., Levine, E., Blanchard, S., and Pendlebury, W.W. 1990. Do temporal relationships in conditioning change across the lifespan? Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 608: 212–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, J.E., Hohmann, C.F., Moran, T.H., and Coyle, J.T. 1988. A long-acting cholinesterase inhibitor reverses spatial memory deficits in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 31: 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, J.E., Bachman, E.S., and Coyle, J.T. 1990. Effects of different doses of galanthamine, a long-acting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, on memory in mice. Psychopharmacology 102: 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L.T. and Disterhoft, J.F. 1997. Age- and dose-dependent facilitation of associative eyeblink conditioning by d-cycloserine in rabbits. Behav. Neurosci. 111: 1303–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L.T., Moyer Jr., J.R., and Disterhoft, J.F. 1996. Transient changes in excitability of rabbit CA3 neurons with a time-course appropriate to support memory consolidation. J. Neurophysiol. 76: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, T., Kaden, B., Fischer, J.P., Bickel, U., Barz, H., Gusztony, G., Cervos-Navarro, J., and Kewitz, H. 1991. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity in human brain tissue and erythrocytes by galanthamine, physostigmine and tacrine. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 29: 487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoesen, G.W. and Solodkin, A. 1994. Cellular and systems neuroanatomical changes in Alzheimer's disease. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 747: 12–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, P.B., Zimmerman, H.J., Knapp, M.J., Gracon, S.I., and Lewis, K.W. 1994. Hepatotoxic effects of tacrine administration in patients with Alzheimer's disease. JAMA 271: 992–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weible, A.P., McEchron, M.D., and Disterhoft, J.F. 2000. Cortical involvement in acquisition and extinction of trace eyeblink conditioning. Behav. Neurosci. 114: 1058–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C., Bouwmeester, H., Power, J.M., and Disterhoft, J.F. 1999. Hippocampal lesions prevent trace eyeblink conditioning in the freely moving rat. Behav. Brain Res. 99: 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C., Preston, A.R., Oh, M.M., Schwarz, R.D., Welty, D., and Disterhoft, J.F. 2000. The M1 muscarinic agonist CI-1017 facilitates trace eyeblink conditioning in aging rabbits and increases the excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 20: 783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonnacott, S. 1997. Presynaptic nicotinic ACh receptors. TINS 20: 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff-Pak, D.S., Vogel, R.W., and Wenk, G.L. 2001. Galantamine: Effect on nicotinic receptor binding, acetylcholinesterase inhibition, and learning. PNAS USA 98: 2089–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yufu, F., Egashira, T., and Yamanaka, Y. 1994. Age-related changes of cholinergic markers in the rat brain. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 66: 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]