Abstract

Objective To examine the cost and cost effectiveness of quarterly CD4 cell count and viral load monitoring among patients taking antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Design Cost effectiveness study.

Setting A randomised trial in a home based ART programme in Tororo, Uganda.

Participants People with HIV who were members of the AIDS Support Organisation and had CD4 cell counts <250 ×106 cells/L or World Health Organization stage 3 or 4 disease.

Main outcome measures Outcomes calculated for the study period and projected 15 years into the future included costs, disability adjusted life years (DALYs), and incremental cost effectiveness ratios (ICER; $ per DALY averted). Cost inputs were based on the trial and other sources. Clinical inputs derived from the trial; in the base case, we assumed that point estimates reflected true differences even if non-significant. We conducted univariate and multivariate sensitivity analyses.

Interventions Three monitoring strategies: clinical monitoring with quarterly CD4 cell counts and viral load measurement (clinical/CD4/viral load); clinical monitoring and quarterly CD4 counts (clinical/CD4); and clinical monitoring alone.

Results With the intention to treat (ITT) results per 100 individuals starting ART, we found that clinical/CD4 monitoring compared with clinical monitoring alone increases costs by $20 458 (£12 780, €14 707) and averts 117.3 DALYs (ICER=$174 per DALY). Clinical/CD4/viral load monitoring compared with clinical/CD4 monitoring adds $142 458, and averts 27.5 DALYs ($5181 per DALY). The superior ICER for clinical/CD4 monitoring is robust to uncertainties in input values, and that strategy is dominant (less expensive and more effective) compared with clinical/CD4/viral load monitoring in one quarter of simulations. If clinical inputs are based on the as treated analysis starting at 90 days (after laboratory monitoring was initiated), then clinical/CD4/viral load monitoring is dominated by other strategies.

Conclusions Based on this trial, compared with clinical monitoring alone, monitoring of routine CD4 cell count is considerably more cost effective than additionally including routine viral load testing in the monitoring strategy and is more cost effective than ART.

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) offers benefits for patients with HIV in resource poor countries that are similar to those reported from industrialised countries. These include reductions in viral load, increases in CD4 cell count, reduced incidence of opportunistic infections, decreased mortality, and improvements in wellbeing and functioning.1 2

In response to worldwide demand and increased funding, implementation of ART is proceeding rapidly in the developing world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.1 The expansion of both treatment and prevention activities is a major development in the global response to HIV/AIDS, and provision of ART is a unique global expansion of resource intensive disease management. A three year home based ART trial in rural Uganda showed the feasibility of achieving excellent health outcomes in a rural African setting.2 National and provincial ART programmes in Malawi, Zambia, South Africa, and elsewhere have shown the capacity to provide high quality and clinically effective ART services on a large scale.3 4 5 In addition to immediate health benefits, ART provides an opportunity for long term enhancement of the capacity of health systems.

These benefits and opportunities notwithstanding, the investment in ART represents an opportunity cost compared with other possible uses of funds to promote global health. Recent global economic changes have resulted in level or reduced funding for HIV prevention and care internationally, even with an increasing number of people affected.1 In addition, the ultimate benefits of spending on ART depend on the choices concerning drugs, technology, and care of patients that can alter its cost effectiveness profile. These include choice of ART drug regimens, work forces for carrying out various aspects of care, and criteria for initiation of treatment and changing drugs.

Among the most important of these choices is the method for monitoring the progression of disease in patients and their response to treatment. The three main approaches are monitoring clinical signs and symptoms; adding laboratory measures of CD cell count to clinical observation; and adding viral load testing to the other two methods. These methods are successively more costly but might be associated with better clinical outcomes. An important question for policy regarding ART treatment is whether laboratory monitoring yields superior outcomes, and, if so, are these benefits large enough to justify the higher costs.

Routine monitoring of viral load and CD4 cell count during ART were adopted in high income countries without studies indicating improved survival compared with careful clinical monitoring. One mathematical model for resource poor settings showed little benefit and considerable cost from routine monitoring of viral load or CD4 cell count during 20 years of follow-up.6 Programmes in Haiti7 and Malawi8 have reported treatment success with clinical monitoring alone, although they lacked comparison with laboratory monitoring. The recent DART trial found favourable results for clinical monitoring over five years of follow-up.9 By reducing routine laboratory monitoring, there is potential for increasing the number of people who could be treated. Such reduction, however, could also lead to premature or delayed changes to second line treatment, more antiretroviral resistance, or increased morbidity.

Previous analyses on the cost effectiveness of different monitoring strategies for ART were based on mathematical models and assumed benefits and suggested a wide range in cost effectiveness.10 We conducted a cost effectiveness analysis of quarterly laboratory monitoring options for ART, based on data from a randomised efficacy trial in Uganda.11 Specifically, we assessed the incremental costs, health gains (disability adjusted life years (DALYs) averted), and cost per DALY averted of adding CD4 counts to clinical monitoring and of adding viral load testing to CD4 counts and clinical monitoring.

Methods

Setting

Tororo District in eastern Uganda has a population of 403 000, of whom 91% live in rural areas and 46% are unable to meet their energy requirements (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, National Household Survey). Most people (80%) earn their living by farming. The annual population growth rate is 2.7%.12 13 In 2005, the prevalence of HIV in adults in this area of Uganda was 5.3%.14

Patients and methods

We conducted two sequential studies among adults with HIV who were clients of the AIDS Support Organization (TASO) in Tororo and Busia Districts, Uganda.11 The first study, started in April 2001, followed participants for five months, then provided daily cotrimoxazole prophylaxis and continued follow-up for an additional 1.5 years. For the second study, we enrolled all clinically eligible participants from the first study and additional participants to achieve a total of 1045 people taking ART.2 This is referred to as the Home-Based AIDS Care (HBAC) programme.

Households were visited weekly by lay providers who re-supplied drugs and administered a standard symptom questionnaire. After enrolment, participants had no routine clinic visits but were encouraged to come to the clinic or hospital for signs and symptoms of toxicity or illness and were taken to the clinic if they had certain defined symptoms. Participants were randomly assigned to three different monitoring regimens: clinical/CD4/viral load (quarterly HIV viral loads and CD4 cell counts, and weekly home visits), clinical/CD4 (quarterly CD4 cell counts and home visits), and clinical (visits alone).11 No other laboratory testing was routinely conducted during follow-up, and serum chemistries were available only just before participants started taking ART. Adherence, as measured by pill counts, was excellent, with only 0.7-2.6% of patients taking less than 95% of pills correctly in any calendar quarter.15 Specific ART regimens are described below.

Overview of analytical methods

We created a spreadsheet based cost effectiveness model to compare the three ART monitoring options during and after the trial described above. Data for health parameters were derived from the trial.11 Intervention costs (monitoring tests and other healthcare) were derived from the trial and other analyses.16 Outcomes calculated per 100 individuals starting ART included costs and DALYs (derived from mortality and morbidity rates) over 15 years. We calculated cost effectiveness ratios as $ per DALY averted, incrementally between strategies. We conducted univariate and multivariate sensitivity analyses.

Cost effectiveness model

Our model was designed to assess the cost and health value of each incremental use of resources for ART monitoring. This incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) is the difference in cost between two monitoring options, divided by the difference in DALYs averted. We compared each monitoring option with the next less expensive alternative. The clinical option was the least expensive, followed by clinical/CD4, and clinical/CD4/viral load. We did not calculate cost effectiveness of clinical/CD4/viral load monitoring compared with clinical monitoring as this would numerically blend the two laboratory monitoring strategies and thus obscure their independent value.

The increase in costs between monitoring options reflects differences in costs per person year for the monitoring tests themselves (that is, CD4 and viral load); differences in costs of antiretroviral regimens (because of unequal rates of progression to more costly second line treatment); and outpatient and inpatient care. These were estimated based on use during the three years’ median follow-up during the trial. Mortality influences total costs by affecting the number of person years of care in each arm. We projected costs of future HIV care associated with the lives saved during the trial to a total of 15 years from start of treatment, using the observed arm specific costs and rates of clinical outcomes during the trial.

The increase in health benefits (that is, DALYs averted) between monitoring options reflects differences in mortality, severe morbidity, and the DALYs incurred with these clinical events. Specifically:

DT=NDA×DD+Σ (NMA×DM)

where DT=total DALYs averted; NDA=number of deaths averted; DD=DALYs averted per death averted; NMA=number of severe morbid events averted; and DM=DALYs averted per morbid event averted.

The DALYs from morbidity are summed across 14 diagnoses. The DALYs associated with mortality are calculated for the three year trial and then over the subsequent 12 years.

Data inputs

We relied mainly on data from the trial to determine the value of health and intervention cost inputs,11 16 17 supplemented by published sources and expert opinion within the trial. Table 1 summarises the data inputs, which are discussed below for the base case. Alternative input values and assumptions are described for the sensitivity analyses.

Table 1.

Model data input values for cost effectiveness analysis, antiretroviral monitoring study, Tororo and Busia Districts, Uganda, 2003-7. All costs are in US $

| Parameter | Base case value | Source(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical/CD4/viral load | Clinical/CD4 | Clinical | ||

| Frequency of health events: | ||||

| Deaths (per 100 person years)* | 3.7 | 4.1 | 5.8 | Trial11 |

| Severe morbid events (per 100 person year)* | 1.7 | 2.7 | 4.9 | Trial11 |

| Disability adjusted life years per clinical event during trial: | ||||

| Deaths | 2.32 | Trial,11 Global Burden of Disease18 | ||

| Severe morbid events (range) | 0.019-0.75 | Global Burden of Disease,18 expert opinion | ||

| Unit costs of monitoring tests: | ||||

| CD4 | $4.68 | $4.68 | — | Downing (Clinton Fund); trial11 |

| Viral load | $29.64 | — | — | COBAS Amplicor; trial11 |

| % Change in antiretroviral drug regimen (annual) | 0.7% | 0.4% | 1.8% | Trial11 |

| Costs of use during trial (per person year): | ||||

| Laboratory monitoring of CD4s and viral loads | $137.30 | $18.74 | $0 | Trial11 |

| Antiretroviral drugs (discounted; observed mix of first and second line regimens during trial) | $160 | $156 | $175 | Trial,11 Médecins Sans Frontières19 |

| Diagnostic tests | $168 | $168 | $164 | Trial11 |

| Opportunistic infection treatment including tuberculosis (outpatient) | $122 | $123 | $127 | Trial11 |

| Inpatient costs | $2.05 | $1.96 | $2.87 | Trial11 |

*From intention to treat analysis, adjusted for multivariate regression findings (see text).

Health inputs

Health events for the baseline analysis reflect the trial’s intention to treat analyses. Point estimates for each monitoring strategy are used, even if differences between study arms were not significant at P=0.05. When multivariate analyses were conducted in the trial, we calculated event rates reflecting the adjusted differences between monitoring arms.

Deaths during the trial were most common in the clinical monitoring arm (5.8 per 100 person years, adjusted), followed by clinical/CD4 monitoring (4.1 per 100 person years, P=0.109 versus clinical), and clinical/CD4/viral load monitoring (3.7 per 100 person years, P=0.698 versus clinical/CD4). Severe morbid events (without death) followed a similar pattern, though at lower absolute rates.

Each death was estimated to cause 2.32 DALYs during the trial, representing two years of lost life on average (deaths were more common toward the start of the trial) and an age disability weight of 1.16 given the average age in this cohort of 39. For severe morbid events (14 different diagnoses), we multiplied the rates in the trial by disability weights18 and by duration (estimated by project clinicians), yielding a wide range in DALYs per event (0.019 to 0.75).

Future longevity and DALYs were modelled from trial completion to 15 years by using arm specific annual mortality rates from the trial. We estimated mean longevity during this 12 year period at 6.43 years (discounted) for clinical, 7.12 for clinical/CD4, and 7.28 for clinical/CD4/viral load. The number of DALYs per arm after the trial quantifies lost health from mortality that occurs both during and after the trial.

Cost inputs

The cost of monitoring is predominantly in the consumable test kit. For CD4 counts, the kit constitutes $3.80 (£2.40, €2.70) of the total $4.68 unit cost and for viral load $27.20 of the total $29.64. The remaining costs are capital, primarily for the test machines, staff, and other costs—such as labelling stickers.

Rates of change of ART from first to second line treatment affect the cost of monitoring strategies. From the trial, the rate of change is highest for clinical (1.8% per year) and similar for clinical/CD4 (0.4%) and clinical/CD4/viral load (0.7%). The annual cost of treatment is $104 for first line ART (stavudine 150 mg, lamivudine 40 mg, and nevirapine 200 mg in a fixed dose pill) and $995 for second line ART (tenofovir 300 mg, didanosine 400 mg, and lopinavir 133.3 mg, and ritonavir 30 mg in a fixed dose pill).19 Different antiretroviral treatment for people coinfected with tuberculosis and the addition of shipping and other ancillary costs raises the average loaded regimen costs for first and second line ART to $125 and $1119 a year, respectively. Furthermore, the cost of first line treatment rises over time (2-4% per month) because of changes in antiretroviral drugs within this regimen.

Table 1 also shows the costs per person year of use of health services in the trial. Differences across monitoring strategies are highest for laboratory monitoring, reflecting quarterly testing: $18.74 for CD4 and $137.30 for CD4 and viral load. The cost of ART varies noticeably by monitoring strategy because of large differences in regimen costs combined with modest differences in change rates. Observed use of diagnostic tests and treatment for opportunistic illnesses varied little (despite sharply different morbidity rates; see sensitivity analyses). Though inpatient costs were higher in the clinical strategy, with daily costs of less than $5 (as is common in the WHO CHOICE database for sub-Saharan Africa) the absolute values are low.16 17 20 Finally, differences in total costs of the arms during the trial reflect differential mortality and thus different total number of person years of receipt of ART.

We estimated the cost of future care of trial survivors based on our simulations out to 15 years, incorporating the arm specific mortality and rates of change of antiretroviral regimens observed during the trial. The future cost per person alive after the trial is $4976 (discounted) for clinical, $4892 for clinical/CD4, and $6043 for clinical/CD4/viral load. Total costs for each arm represent the product of cost per person and the number alive of the original 100 in the arm.

Comparison with cotrimoxazole

We examined the cost effectiveness of ART overall and of the least expensive ART arm (clinical monitoring) compared with treatment with cotrimoxazole alone. This extends an earlier analysis that compared the entire ART cohort at two years with cotrimoxazole.17 The cotrimoxazole comparison results are from a different trial in the same population. We included this comparison because some readers might be interested in the cost effectiveness comparison of ART versus cotrimoxazole alone, given that HIV care resources are increasingly constrained in Africa and a decreasing proportion of people with HIV will be able to access ART. Thus, the analysis provides comparisons in a cohort of people with HIV across the broad continuum of care from cotrimoxazole to ART with clinical monitoring, to ART with clinical and laboratory monitoring. We have included only the clinical benefits to the patient (not prevention of HIV transmission and other outcomes), so the results might not be precisely comparable.

Sensitivity analyses

We examined the effect of uncertainty in inputs and modelling assumptions on the ICERs. We varied individual parameter values (such as the relative mortality across monitoring arms and costs of monitoring tests), as well as broader decisions (such as using intention to treat versus per protocol trial results, and limiting the analysis to the trial period). We used Monte Carlo simulations to portray the impact of simultaneous variation in key inputs.

Results

Base case

During the three year trial, the clinical strategy cost the least ($190 570 per 100 individuals starting the arm), followed by clinical/CD4 ($194 844), and clinical/CD4/viral load ($229 521) (table 2). The most important difference in cost across arms was monitoring, with a smaller difference for antiretroviral drugs. Total costs over 15 years follow a similar pattern, at $606 260, $626 718, and $769 177, respectively. The difference in total costs was $20 458 for clinical/CD4 versus clinical and $142 458 for clinical/CD4/viral load versus clinical/CD4 (table 3).

Table 2.

Cost and health outcomes by monitoring strategy (per 100 people starting each arm), for cost effectiveness analysis, antiretroviral monitoring study, Tororo and Busia Districts, Uganda, 2003-7

| Clinical/CD4/viral load | Clinical/CD4 | Clinical | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Costs ($) | |||

| Total during trial (three years) | 229 521 | 194 844 | 190 570 |

| Laboratory monitoring CD4 and viral load* | 38 142 | 5164 | 0 |

| Antiretroviral drugs* | 44 402 | 42 897 | 46 370 |

| Total after trial | 539 656 | 431 874 | 415 690 |

| Total | 769 177 | 626 718 | 606 260 |

| Health outcomes | |||

| DALYs during trial | 27.1 | 30.5 | 44.4 |

| Deaths | 11.1 | 12.2 | 17.5 |

| DALYs from deaths | 25.8 | 28.3 | 40.5 |

| DALYs from opportunistic infections | 1.36 | 2.17 | 3.90 |

| Future DALYs | 294.5 | 318.6 | 422.0 |

| Total DALYs | 321.6 | 349.1 | 466.4 |

*Selected cost detail presented to show major variation across strategy.

Table 3.

Incremental costs, DALYs, and cost effectiveness ratios for antiretroviral monitoring study, Tororo and Busia Districts, Uganda, 2003-7

| Cost ($) | Incremental cost ($) | DALYs incurred | Incremental DALYs averted | ICER: $ per DALY averted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | 606 260 | — | 466.4 | — | — |

| Clinical/CD4 | 626 718 | 20 458 | 349.1 | 117.3 | 174 |

| Clinical/CD4/viral load | 769 177 | 142 458 | 321.6 | 27.5 | 5181 |

DALYs were determined almost entirely by mortality. During the trial, the most deaths (17.5 per 100 individuals starting the arm) and the most DALYs (44.4 per 100 individuals starting the arm, including 40.5 deaths) occurred in the clinical strategy arm. The figures for DALYs were 30.5 (28.3 deaths) in the clinical/CD4 arm and 27.1 (25.8 deaths) in the clinical/CD4/viral load arm. After the trial, DALYs continued to reflect differential mortality by arm and were about 10 times higher than DALYs incurred during the trial: 422.0, 318.6, and 294.5 for the three arms, respectively. The DALY total after the trial is high because each death, whether during or after the trial, incurs DALYs in each subsequent year. Total DALYs were 466.4 for clinical, 349.1 for clinical/CD4, and 321.6 for clinical/CD4/viral load. The difference in estimated total DALYs was 117.3 for clinical versus clinical/CD4 and 27.5 for clinical/CD4 versus clinical/CD4/viral load (table 3).

Table 3 shows incremental costs, health outcomes, and cost effectiveness. The incremental comparisons of interest, guided by the order of increasing cost, are clinical/CD4 versus clinical and clinical/CD4/viral load versus clinical/CD4. For the base case, each increase in cost is associated with increased health benefits (that is, fewer DALYs incurred), so no strategy is “dominated.”

The cost per DALY averted was $174 for clinical/CD4 versus clinical and $5195 for clinical/CD4/viral load versus clinical/CD4. The 30-fold higher ICER for the second comparison is because of sevenfold higher incremental costs and three quarters lower difference in DALYs.

Comparison with cotrimoxazole

The cost of a cotrimoxazole strategy was $9299 for 100 individuals over 15 years.16 This reflects $50 per person year and reduced survival (and thus person years of care) compared with ART. DALYs over 15 years total to 1160. Thus, compared with cotrimoxazole, ART with clinical monitoring adds $596 961 and averts 693.7 DALYs for an ICER of $861 per DALY averted. ART overall (all three arms combined) adds $658 086 and averts 781.1 DALYs for an ICER of $843 per DALY averted. The second ICER is lower (by 2.1%) because of the attractive ICER of going from clinical to clinical/CD4. As noted above, these ICERs consider only the clinical value to the individual receiving treatment, omitting the health and cost effects associated with prevention and other benefits of ART, and thus are higher than the more inclusive ICERs below.

Implications for ART programming

We estimate $518 per DALY averted for ART with the clinical/CD4 strategy versus cotrimoxazole, based on the previous finding of $573 per DALY averted for ART (all arms) versus cotrimoxazole17 and the lower ICER when CD4 is added to clinical monitoring. We estimated $637 per DALY averted for ART with clinical/CD4/viral load versus cotrimoxazole because of higher monitoring and costs of antiretrovirals. If a national programme has $100 million to spend for ART, a mean cost of $518 per DALY averted implies that 193 145 DALYs could be averted. If instead, the same money was spent at $637 per DALY averted, then 156 935 DALYs could be averted. The difference of 36 210 DALYs represents the potential health loss of allocating programme funds to viral load testing instead of starting more people on ART with clinical and CD4 monitoring. From the cost perspective, an additional $23 million would be needed to include viral load testing with no change in DALYs.

Sensitivity analyses

Table 4 reports the effect on ICERs of variation in key inputs and modelling assumptions. We examined uncertainty in the mortality rate as suggested by the 95% confidence intervals for observed adjusted hazard ratios in the intention to treat analysis. For clinical/CD4/viral load, with the most favourable hazard ratio and mortality rate, the ICER drops below $1600. With the worst mortality, the clinical/CD4/viral load strategy is dominated by clinical/CD4 (more expensive and less effective). For clinical/CD4, lower mortality worsens the ICER because the ICER approaches the cost effectiveness of keeping individuals alive on ART (that is, cost and a year’s DALYs v death and no cost). When mortality is higher, the clinical/CD4 arm becomes less expensive and effective than clinical, so the ICER is calculated in the reverse direction.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses for key inputs and modelling assumptions for cost effectiveness analysis, antiretroviral monitoring study, Tororo and Busia Districts, Uganda, 2003-7

| Input or assumption | Values/methods used | Most/least favourable ICER ($/DALY averted) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base case | Most/least favourable* | Clinical/CD4 (v clinical) | Clinical/CD4/viral load (v clinical/CD4) | ||

| Deaths per 100 person years (intention to treat): | |||||

| Clinical/CD4/viral load, 95% CI†, other arms kept at base case | 3.7 | 2.22/6.11 | 174/174 | 1550/dominated‡ | |

| Clinical/CD4, 95% CI†, other arms kept at base case | 4.1 | 2.55/6.48 | 368/1792§ | Dominated‡/1263 | |

| Clinical, 95% CI†, other arms kept at base case | 5.8 | 9.10/3.70 | 454/2832§ | 5181/5181 | |

| Deaths per 100 person years (per protocol): | |||||

| Viral load arm, CD4 arm, clinical arm | Intention to treat (above) | NA/2.2, 2.0, 3.5 | NA/88 | NA/dominated‡ | |

| Annual rate of regimen change: | |||||

| Viral load arm, CD4 arm, clinical arm | 0.7%, 0.4%, 1.8% | 50-150% of base case values | 401/dominant‡ | 4882/5466 | |

| Future DALYs averted and costs added per death: | |||||

| Inclusion or exclusion of projections beyond trial | Included | NA/excluded | NA/307 | NA/10 257 | |

| Unit costs of monitoring test kits: | |||||

| CD4 | 3.80 | 1.90/5.70 | 233/115 | 5187/5175 | |

| Viral load | 27.20 | 13.60/54.40 | 176/173 | 3322/7040 | |

| Costs of antiretroviral drugs (annual; per person): | |||||

| First line regimen | 125 | 63/188 | 73/275 | 5169/5193 | |

| Second line regimen | 1119 | 557/1679 | 451/dominant‡ | 4825/5538 | |

| Costs of opportunistic infection treatment: | |||||

| Observed (base case) v imputed from rates of opportunistic infection | 122, 123, 127 | 97, 123, 194/NA | 1.06/NA | 4906/NA | |

NA=not applicable.

*For cost effectiveness of laboratory testing.

†95% CI from clinical trial.11

‡Dominated=higher cost and fewer DALYs than comparator; dominant=cheaper and better.

§ICER for high end of mortality range represents reverse comparison among arms.

The trial’s per protocol (as treated) analysis examined only the period after monitoring began (at 90 days), removing the early period of high mortality unrelated to ART monitoring. This analysis found adjusted mortality rates of 2.2, 2.0, and 3.5 per 100 patient years for the clinical/CD4/viral load, clinical/CD4, and clinical arms, respectively. The clinical/CD4 arm had an ICER of $88 per DALY averted compared with clinical alone, and the viral load option was dominated compared with the clinical/CD4 arm.

Varying the rate of change in regimen between 50% and 150% of base case values (for all arms simultaneously) had little effect on the ICER for viral load ($4882-5466). It has a proportionately larger effect on the ICER for CD4 versus clinical ($401-“dominant”). This is because of the small and similar switch rates in clinical/CD4/viral load and clinical/CD4 arms and the larger base case value of regimen switch rates in the clinical arm.

When we limited the analysis to the trial period (instead of estimating future DALYs averted and costs added), the ICER for clinical/CD4 versus clinical was $307, 176% above the base case value ($174). This difference reflects the lower long term cost per person year on ART for clinical/CD4 (because of a lower rate of change in antiretroviral regimen) than for clinical. The ICER for viral load versus CD4 rose more sharply to $10 257, 198% above the base case value ($5181). This ICER is more attractive after than during the trial for a different reason: the increasing role in the analysis of the difference in person years on ART (which has an ICER for this arm of about $600 per DALY).

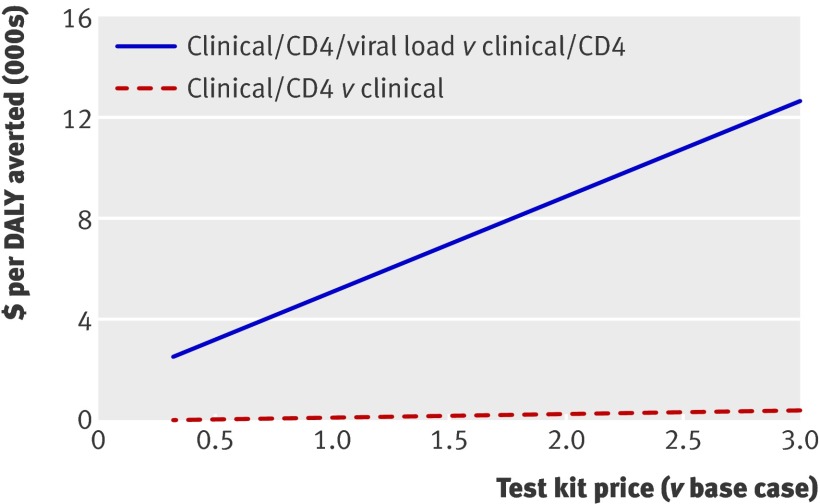

The unit cost of monitoring test kits had more impact on the ICER for viral load than for CD4. Halving the cost of CD4 test kits decreased the ICER to $117 (67% of base case). When the cost of the viral load test kit is reduced to 50% of its base case value, the ICER for viral load decreases to $3 316 (64% of base case). Doubling the cost increased the ICERs to $289 (166% of base case) and $8911 (172% of base case) for CD4 and viral load, respectively. The figure shows the same contrast in sensitivity for the range from one third to three times the base case unit cost.

Sensitivity analysis: price of test kits for cost effectiveness analysis, antiretroviral monitoring study, Tororo and Busia Districts, Uganda, 2003-7

The cost of antiretroviral drugs has the expected effects on the ICERs. The ICER for clinical/CD4 versus clinical is much more affected than the other ICER because of the large difference in rates of change in regimen between these arms. Lower costs of first line regimens favour clinical/CD4 over clinical (that is, they lower the ICER), as do higher costs of second line regimens.

When we replaced observed costs for treatment of opportunistic infections (drugs and visits; nearly equal across arms) with costs forced to be proportional to observed opportunistic infections rates, the ICER decreased to $1 for CD4 monitoring and increased to $4906 for viral load monitoring.

We used a 50 000 trial Monte Carlo simulation (Crystal Ball 7.3, Denver, CO) to assess the aggregate uncertainty from all varied inputs in the intention to treat analysis. In the absence of information about the distribution of input values, we fitted β distributions, with maximum and minimum values set to 50% and 150% of the base case value, around each variable of interest. The α and β parameters were set to three, ensuring a symmetrical distribution approximating the normal with the base case as the mean value.21 The only exception was mortality for the CD4 arm (which had a range corresponding to the 95% confidence interval of the hazard ratio). The other variables included in the simulation were the discount rate, the cost of laboratory tests, the annual rate of regimen changes, and the costs of first line and second line antiretroviral drugs. First line and second line drug costs were correlated at 0.50. We found that clinical/CD4 had an ICER between “dominant” and $421 per DALY averted (95% confidence interval), and is less than $0 (dominates clinical) in 24.2% of trials. Clinical/CD4/viral load had an ICER between less than $0 per DALY averted (dominated) and $43 479 (95% confidence interval). Clinical/CD4/viral load is dominated by CD4 in 27.7% of trials.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This analysis of the cost effectiveness of ART monitoring strategies in Africa, which uses empirical data from an ART monitoring trial, found that adding routine monitoring of CD4 cell counts to clinical monitoring was more cost effective than the further addition of viral load monitoring. Adding CD4 cell count to clinical monitoring at $174 per DALY averted was more efficient than putting an additional person on ART in the same setting ($573 per DALY17). Adding viral load to clinical and CD4 monitoring had a cost per DALY averted of $5168—that is, nearly 10 times higher. Sensitivity analyses suggested that viral load testing could cost up to $14 000 per DALY averted and had a 25% chance of being dominated—that is, of being both more expensive and less effective than CD4 monitoring—because of substantially overlapping confidence intervals for clinical outcomes in the different monitoring arms. When we used the as treated (per protocol) results from the trial, the clinical/CD4/viral load arm was dominated by clinical/CD4. Thus, our analysis suggests that both CD4 monitoring and starting a patient on ART are economically preferable to monitoring viral load.

These findings are within the range of modelled cost effectiveness of ART monitoring in Africa.10 22 The DART study, the only other randomised controlled trial of ART monitoring in Africa, found improved clinical outcomes with CD4 compared with clinical monitoring after two years’ receipt of ART. The estimated cost effectiveness ratio, however, was above $1200 per DALY averted (exact value not reported) because of a higher switching rate to more expensive second line antiretroviral regimens.9 In our study, regimen switching was less common with CD4 monitoring. The higher change rate for the clinical arm was unexpected. However, it makes sense considering that in the clinical monitoring arm, for participants with symptoms potentially indicating failure of ART (such as a new or recurrent CDC category C condition, chronic diarrhoea, or candidiasis), clinicians lacked access to monitoring to detect whether patients were immunologically responding to treatment or were virologically suppressed. This probably increased the frequency of drug switching. By contrast, in the clinical/CD4 arm, patients with a clinical event that indicated consideration for switching could be retained on first line treatment if their CD4 cell count remained high. Details of the clinical monitoring and regimen change protocols are included in the report of the randomised controlled trial.11

Limitations

There are important limitations to our study. We treated mortality comparisons, which dominate our model’s health and cost effects, as meaningful regardless of statistical significance. Thus, the base case results reflect observed differences in mortality that were small and not quite significant for clinical/CD4 versus clinical monitoring (combined mortality and AIDS defined events were significantly different) and far from significant for clinical/CD4/viral load versus clinical/CD4 monitoring . As a result, they could be considered overly optimistic. Despite this lenient approach (counting as real a difference for which there is little evidence), viral load had a highly unfavourable ICER. Our sensitivity analyses highlight how the uncertainty about these comparisons contributes to a substantial likelihood that viral load monitoring is dominated. Furthermore, in the per protocol analysis, which is arguably appropriate for an intervention that starts three months after the initiation of treatment, the clinical/CD4/viral load arm had a mortality point estimate slightly higher than the clinical/CD4 arm.

We lacked data on mortality rates beyond the trial. To calculate long range ICERs, we assumed ongoing arm specific mortality rates as observed in the trial. The assumption of higher or lower rates after the trial, however, did not change our findings qualitatively—that is, clinical/CD4 monitoring retained its superior cost effectiveness. Specifically, lower long term mortality, as observed late in the trial, led to a more attractive ICER for clinical/CD4 versus clinical monitoring, and higher mortality increases the ICER just 50%. Within trial ICERs generate similar results. Thus, our findings seem robust to uncertainties in mortality.

This trial had high levels of adherence to ART, low rates of virological failure, low rates of regimen switching, and low mortality. Adherence was similar to the highest levels observed in African settings.23 Also, adherence was higher and virological failure was lower than observed in another recent Ugandan trial.24 This limits the generalisability of our study as we could not explore the role of viral load monitoring in the context of high short or long term failure of suppression of viral load. The economic implications of lower adherence are uncertain as the clinical/CD4 arm in our study was efficient in guiding regimen change while improving clinical outcomes. In our sensitivity analyses, higher overall rates of regimen change led to the clinical/CD4 arm being dominant (lower cost and better outcomes) by magnifying these favourable empirical trial findings. In addition, in settings with low adherence, it might be more cost effective to implement low cost adherence interventions such as counselling and pill counts before viral load testing. Direct study of the unique contribution and cost of viral load monitoring in less adherent populations would be extremely valuable (after reasonable measures to increase adherence) and should include resistance testing.

The study had a home based component and was thus structurally atypical. The relative cost effectiveness among groups, however, is likely to be similar to facility based programmes as the overall cost effectiveness of ART was similar to facility based analyses in the Côte d’Ivoire and South Africa.25 26 In addition, all three strategies used quarterly monitoring. In some countries, governments promote biannual monitoring. Results for less frequent monitoring might differ from ours.

We did not examine the benefits of ART in preventing HIV transmission. In settings where viral load monitoring improves rates of full viral suppression, there would probably be benefits. These might not be as great as initially assumed as the effect of reduced viral load on HIV transmission is not dichotomous; even a plasma viral load of 5000-10 000 copies/mL would reduce the risk of transmission considerably compared with 500 000 copies/mL. Thus, the effect of identifying relatively slight increases in viral load a few weeks or months earlier could be less important than efforts to increase access to ART and retention in care.

We did not assess all plausible configurations of laboratory monitoring. For example, a strategy including clinical and virological but not CD4 monitoring could potentially reduce costs while detecting virological failure early. Viral load might be a better indicator than CD4 cell counts of treatment success and thus clinically advantageous. Yet our study did not indicate improved efficacy from adding viral load to CD4 monitoring. Furthermore, logistical challenges to viral load monitoring are substantial in Africa. CD4 cell counts are more widely available in peripheral health centres because of lower costs, ease of operation and maintenance, and use for determining eligibility for ART. Reliance on viral load could potentially work with efficient referral to a central laboratory or new technology, but currently in Uganda, routine viral load monitoring is unlikely to be feasible outside a research setting or major cities. As less expensive and logistically simpler viral load testing becomes available, a study comparing routine CD4 cell count monitoring with routine viral load monitoring alone would be valuable.

Implications

Standards in clinical practice well attuned to resource rich settings might not maximise the opportunities available in resource constrained settings. Monitoring CD4 cell counts seems desirable clinically and economically in these settings. In contrast, viral load monitoring might be a relatively poor investment compared with offering ART to another person or monitoring CD4 cell counts for those currently taking ART. This approach supports current WHO guidelines.27

According to WHO, the attractiveness of the ICER can be determined by comparison with the country’s annual gross domestic product per capita. An intervention with an ICER below the annual gross domestic product per capita is considered “very cost effective.” An ICER below three times the annual gross domestic product per capita is considered “cost effective.”28 The annual gross domestic product per capita in Uganda in 2008 was an estimated 1200 international dollars ($485 using currency exchange rates).13 Thus by the gross domestic product per capita standard, CD4 count monitoring is “very cost effective” and viral load monitoring is not cost effective.

In closing, we want to highlight another path to increased access to high quality ART in resource poor settings. We strongly support efforts to reduce the price of second line antiretroviral regimens and laboratory tests. If such efforts could replicate the impressive past decreases in the price of first line regimens and the also important reductions for CD4 counts, the types of analyses reported here would be less necessary.

What is already known on this topic

ART in sub-Saharan Africa costs $500 to $1000 per disability adjusted life year (DALY) averted

Previous estimates of the cost effectiveness of laboratory monitoring relied on computer simulation models and varied widely

What this study adds

Adding routine monitoring of CD4 count costs $174 per DALY averted, less than for ART. CD4 monitoring is cost effective by improving clinical outcomes and reducing changes to more expensive antiretroviral drugs

Adding routine monitoring of viral load costs $5181 per DALY averted, far more than for ART or CD4 monitoring and in a subset of analyses is both less effective and more costly than clinical or CD4 monitoring. Viral load monitoring has unattractive cost effectiveness because of low clinical benefit and high test costs

Contributors: JGK and EM designed the analysis, constructed the cost effectiveness model, and wrote the manuscript. DM, RD, and JM provided data and interpretation for the clinical trial results. RD and PE provided healthcare use and cost data from the trial. DM, RB, WW, JWT, PE, FK, and JM reviewed and edited the manuscript to assure accurate interpretation and representation of the trial context, clinical practices, and economic findings. JGK is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Kenya, and US National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01 DA15612). The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the science and ethics committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute, the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology; CDC Institutional Review Board; UCSF CHR 04024782.

Data sharing: Detailed costing data available on request.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d6884

References

- 1.UNAIDS. 2010 report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS, 2010. www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ug.html.

- 2.Mermin J, Were W, Ekwaru JP, Moore D, Downing R, Behumbiize P, et al. Mortality in HIV-infected Ugandan adults receiving antiretroviral treatment and survival of their HIV-uninfected children: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2008;371:752-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tweya H, Gareta D, Chagwera F, Ben-Smith A, Mwenyemasi J, Chiputula F, et al. Early active follow-up of patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) who are lost to follow-up: the ‘Back-to-Care’ project in Lilongwe, Malawi. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15(suppl 1):82-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornell M, Grimsrud A, Fairall L, Fox MP, van Cutsem G, Giddy J, et al. Temporal changes in programme outcomes among adult patients initiating antiretroviral therapy across South Africa, 2002-2007. AIDS 2010;24:2263-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi BH, Mwango A, Giganti MJ, Sikazwe I, Moyo C, Schuttner L, et al. Comparative outcomes of tenofovir- and zidovudine-based antiretroviral therapy regimens in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011. Aug 18 (epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Phillips AN, Pillay D, Miners AH, Bennett DE, Gilks CF, Lundgren JD. Outcomes from monitoring of patients on antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings with viral load, CD4 cell count, or clinical observation alone: a computer simulation model. Lancet 2008;371:1443-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koenig SP, Leandre F, Farmer PE. Scaling-up HIV treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: the rural Haiti experience. AIDS 2004;18(suppl 3):S21-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harries AD, Schouten EJ, Libamba E. Scaling up antiretroviral treatment in resource-poor settings. Lancet 2006;367:1870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dart Trial Team, Mugyenyi P, Walker AS, Hakim J, Munderi P, Gibb DM, et al. Routine versus clinically driven laboratory monitoring of HIV antiretroviral therapy in Africa (DART): a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2010;375:123-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walensky RP, Ciaranello AL, Park JE, Freedberg KA. Cost-effectiveness of laboratory monitoring in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of the current literature. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:85-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mermin J, Ekwaru JP, Were W, Degerman R, Bunnell R, Kaharuza F, et al. Utility of routine viral load, CD4 cell count, and clinical monitoring among adults with HIV and receiving antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: randomised trial. BMJ 2011;d6792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Wikipedia. Tororo district government. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tororo_District.

- 13.US Central Intelligence Agency: Africa-Uganda. World Factbook, 2010. www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ug.html.

- 14.Ministry of Health (MOH) (Uganda) and ORC Macro. Uganda HIV/AIDS sero-behavioural survey 2004-2005. Ministry of Health and ORC Macro, 2006.

- 15.Weidle PJ, Wamai N, Solberg P, Liechty C, Sendagala S, Were W, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a home-based AIDS care programme in rural Uganda. Lancet 2006;368:1587-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitter C, Kahn JG, Marseille E, Lule JR, McFarland DA, Ekwaru JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis among persons with HIV in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;44:336-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marseille E, Kahn JG, Pitter C, Bunnell R, Epalatai W, Jawe E, et al. The cost effectiveness of home-based provision of antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2009;7:229-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Disease Control Priorities Project. The global burden of disease. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- 19.Médecins Sans Frontières. Untangling the Web of ARV Price Reductions: a pricing guide for the purchase of ARVs for developing countries, 10th ed. MSF, 2007.

- 20.Murru M, Corrrado B, Odaga J, Ahairwe D, Akulu E, Bavcar A, et al. Costing health services in Lacor Hospital. Health Policy and Development Journal. Department of Health Sciences of Uganda Martyrs University, 2003:61-8.

- 21.Morgan MG, Henrion M, Small M. Uncertainty : a guide to dealing with uncertainty in quantitative risk and policy analysis. Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- 22.Kimmel AD, Weinstein MC, Anglaret X, Goldie SJ, Losina E, Yazdanpanah Y, et al. Laboratory monitoring to guide switching antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;54:258-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, Orbinski J, Attaran A, Singh S, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2006;296:679-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffar S, Amuron B, Foster S, Birungi J, Levin J, Namara G, et al. Rates of virological failure in patients treated in a home-based versus a facility-based HIV-care model in Jinja, southeast Uganda: a cluster-randomised equivalence trial. Lancet 2009;374:2080-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldie SJ, Yazdanpanah Y, Losina E, Weinstein MC, Anglaret X, Walensky RP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HIV treatment in resource-poor settings—the case of Cote d’Ivoire. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1141-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleary SM, McIntyre D, Boulle AM. The cost-effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment in Khayelitsha, South Africa—a primary data analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2006;4:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Priority interventions: HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care in the health sector. WHO, 2010.

- 28.Edejer T, Baltussen T, Hutubessy R, Acharya A, Evans D, Murray C. Making choices in health: WHO guide to cost-effectiveness analysis. In: WHO guide to cost-effectiveness analysis. World Health Organization, 2003. www.who.int/choice/publications/p_2003_generalised_cea.pdf.