Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Primary care providers often care for men with prostate cancer due to its prolonged clinical course and an increasing number of survivors. However, their attitudes and care patterns are inadequately studied. In this context, we surveyed primary care providers regarding the scope of their prostate cancer survivorship care.

METHODS

The 2006 Early Detection and Screening for Prostate Cancer Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice Survey conducted by the Michigan Public Health Institute investigated the beliefs and practice patterns of primary care providers in Michigan. We evaluated responses from 902 primary care providers regarding the timing and content of their prostate cancer survivorship care and relationships with specialty care.

RESULTS

Two-thirds (67.6%) of providers cared for men during and after prostate cancer treatment. Providers routinely inquired about incontinence, impotence and bowel problems (83.3%), with a few (14.2%) using surveys to measure symptoms. However, only a minority felt ‘very comfortable’ managing the side effects of prostate cancer treatment. Clear plans (76.1%) and details regarding management of treatment complications (65.2%) from treating specialists were suboptimal. Nearly one-half (45.1%) of providers felt it was equally appropriate for them and treating specialists to provide prostate cancer survivorship care.

CONCLUSIONS

Primary care providers reported that prostate cancer survivorship care is prevalent in their practice, yet few felt very comfortable managing side effects of prostate cancer treatment. To improve quality of care, implementing prostate cancer survivorship care plans across specialties, or transferring primary responsibility to primary care providers through survivorship guidelines, should be considered.

Keywords: prostate cancer, survivorship, primary care, attitudes, knowledge, practice patterns

INTRODUCTION

With over 2 million survivors and nearly $7 billion in national health expenditures annually, prostate cancer is one of the most prevalent and expensive cancers in the U.S.1,2 Under current screening practices, 1 out of 6 men will be diagnosed with the disease during their lifetime.3 The downstream consequences of that diagnosis may include significant detriments to urinary control, sexual function and overall quality of life.4 Because the disease and side effects of its treatment are so common, understanding how to optimize the delivery of prostate cancer survivorship care has significant quality of care implications.

Due to the prolonged natural history of the disease and the sheer number of prostate cancer survivors, primary care providers inevitably care for these men. However, their role in prostate cancer survivorship care remains undefined. The timing, content, and processes of prostate cancer survivorship care among primary care providers have been understudied. For example, how they care for treatment-related side effects (incontinence, impotence) or address other prostate cancer survivorship issues is largely unknown. Moreover, primary care and oncology specialties have not established a consensus on who is responsible for routine survivorship care (i.e., monitoring for disease recurrence, treating side effects, counseling regarding general health, and screening for other malignancies).5 Such uncertainty fosters fragmented care potentially leading to duplicate services,6 patient inconvenience, and increased cost.7,8

Describing primary care provider involvement during prostate cancer survivorship may help identify opportunities to improve care coordination and optimize quality of care. Therefore, the Michigan Cancer Consortium, a state-wide non-profit collaborative of cancer care institutions and the Michigan Public Health Institute, surveyed primary care providers in the State of Michigan to better understand their beliefs and practice patterns with regard to prostate cancer survivorship.

METHODS

Study Design

The Early Detection and Screening for Prostate and Colorectal Cancer Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice (KAP) Survey was developed by the Michigan Public Health Institute in collaboration with primary care providers, urologists, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, and nurses affiliated with the Prostate Cancer Action Committee of the Michigan Cancer Consortium.9 The survey was intended to characterize the following aspects of prostate cancer survivorship care by primary care providers: 1) the types of prostate cancer care delivered; 2) the degree of communication with treating specialists regarding their patients’ survivorship care; 3) the comfort level with treating survivors’ incontinence, impotence, bowel problems and psychosocial concerns; 4) preferred treatments (e.g., medication, referral) for managing prostate cancer treatment-related side effects; 5) opinions of who is the most appropriate to provide survivorship care (i.e., primary care provider, treating specialist, survivorship clinic); and 6) the degree to which they addressed urinary and sexual symptoms during survivorship. All survey data were entered into a central database maintained at the Michigan Public Health Institute. Informed consent from each of the respondents was obtained. The Institutional Review Boards of the Michigan Public Health Institute and the Michigan Department of Community Health approved the study.

Study Population

In 2006, the KAP survey was mailed in a staggered fashion to all primary care providers and a random sample of nurse practitioners and physician assistants licensed to practice in the State of Michigan. Primary care provider addresses were identified from a state-wide database maintained by a private vendor and verified using data from the Michigan Bureau of Health Professionals. Addresses for nurse practitioners and physician assistants were obtained from the State of Michigan's Licensing Division. The survey included a cover letter describing the purpose of the study as well as entry into a drawing for a cash prize of $575 as an incentive. Recipients were instructed to return the survey within two weeks and up to two reminder postcards were sent out.

The survey was completed by 902 of an estimated 5,687 eligible respondents (15.9% response rate). Due to the sampling frame, the majority of the primary care provider respondents were physicians (74.3%). Primary care nurse practitioners had the greatest the response rate (n=121, 18.3%), followed by physicians (n=670, 15.7%) and physician assistants (n=111, 14.3%).

Statistical Analysis

To determine the response percentage for each item, the total number of responses per survey item was used as the denominator. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the characteristics of primary care providers and their practices. To ascertain whether differences in comfort levels managing prostate cancer treatment-related side effects existed among the 3 primary care provider types (physician, nurse practitioner and physician assistant), we used the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test.

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, just over half of primary care providers responding to the survey were male (53.7%), most were white (83.8%), and nearly two-thirds (64.8%) were over the age of 45. Among respondents, two-thirds (67.6%) cared for men following a diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating primary care providers and their practices

| Characteristic |

Value |

|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |

| Female | 46.3 |

| Male |

53.7 |

| Age | |

| Median (range, years) | 50 (24-88) |

| Over 45 years (%) |

64.8 |

| Years since graduating medical program (%) | |

| 10 or less | 25.5 |

| 11 to 20 | 26.4 |

| 21 to 30 | 29.6 |

| Greater than 30 |

18.5 |

| Race (%) | |

| White/Caucasian | 83.8 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 7.3 |

| Black/African American | 2.9 |

| Middle Easterner | 1.9 |

| Hispanic | 1.5 |

| Other |

2.6 |

| Medical practice type (%) | |

| Single specialty group practice | 36.7 |

| Solo private practice | 23.3 |

| Multi-specialty group | 13.5 |

| Teaching facility | 12.2 |

| Other | 11.8 |

| Urgent care |

2.6 |

| Affiliated with a cancer center (%) | |

| Yes | 26.2 |

| No |

73.8 |

| Distance from nearest cancer center (%) | |

| <5 miles | 50.9 |

| 5-10 miles | 17.1 |

| 10-20 miles | 14.2 |

| >20 miles |

17.9 |

| Number of patients treated monthly (%) | |

| <200 | 36.0 |

| 201-399 | 28.5 |

| 400-499 | 22.5 |

| 500-599 | 7.7 |

| 600-999 | 4.5 |

| >999 | 0.7 |

While the timing and content of their cancer care varied, primary care providers reported that they were involved in a wide variety of prostate cancer survivorship care. Approximately two-thirds participated in treatment decision making (64.5%) and symptom management during active treatment (63.4%). Moreover, the rate of post-treatment symptom management rose to 83.0%, with three-quarters (78.4%) of primary care providers reporting that they performed periodic monitoring for their prostate cancer survivors. Nearly all primary care providers believed that patients were receiving follow up care with their treating specialist during the first year after treatment (98.3%).

As shown in Table 2, only a minority of primary care providers felt ‘very comfortable’ managing the side effects of prostate cancer treatment. Although there were no differences between the comfort levels of physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants with treating urinary incontinence (p=0.09), differences in comfort levels did exist among various providers when treating impotence (p=0.02), bowel problems (p=0.01) and psychosocial concerns (p=0.02). In addition to prescribing anticholinergics (74.8%) and erectile dysfunction medications (89.3%), referrals to urologists for the treatment of incontinence (89.6%) and impotence (84.0%) were common among primary care providers.

Table 2.

| Side effect | Very uncomfortable (%) | Somewhat comfortable (%) | Very comfortable (%) | p -value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary incontinence | 0.09 | |||

| Physician | 12.2 | 75.6 | 12.2 | |

| Nurse practitioner | 19.2 | 73.1 | 7.7 | |

| Physician assistant | 21.8 | 65.5 | 12.7 | |

| Impotence | 0.02 | |||

| Physician | 10.6 | 68.2 | 21.2 | |

| Nurse practitioner | 19.2 | 65.4 | 15.4 | |

| Physician assistant | 21.8 | 61.8 | 16.4 | |

| Bowel problems | 0.01 | |||

| Physician | 10.0 | 69.8 | 20.2 | |

| Nurse practitioner | 19.2 | 59.6 | 21.2 | |

| Physician assistant | 21.8 | 67.3 | 10.9 | |

| Psychosocial concerns | 0.02 | |||

| Physician | 9.0 | 56.5 | 34.5 | |

| Nurse practitioner | 17.3 | 46.2 | 36.5 | |

| Physician assistant | 12.7 | 69.1 | 18.2 |

n=606

Physician includes allopathic (MD) and osteopathic physicians (DO)

Despite a lack of comfort with treating prostate cancer treatment-related side effects, providers appeared comfortable asking about them. For example, the majority of providers routinely inquired about survivors’ incontinence, impotence and bowel problems (83.3%) – although only 14.2% used surveys or questionnaires to measure urinary and sexual symptoms. In addition, nearly all providers kept prostate cancer as a diagnosis on the patient's active issue list (97.2%). In terms of oncologic processes of care, primary care providers reported routinely recommending referral back to specialists for a rising PSA (99.3%) or per patient request (97.2%).

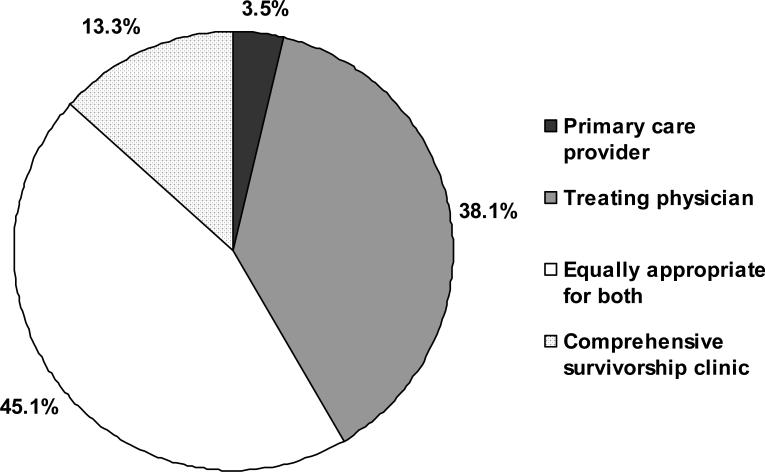

As illustrated in Figure 1, nearly one-half (45.1%) of primary care providers felt it was equally appropriate for them and the treating specialists to provide prostate cancer care for survivors. Only 3.5% of primary care providers believed their specialty was the most appropriate to provide survivorship care, while 13.3% felt comprehensive survivorship clinics were the most appropriate. Among primary care providers caring for prostate cancer survivors, communication from treating specialists was fair. Adequate communication (81.2%), clear treatment plans (76.1%), and details regarding treatment complications and their management (65.2%) were not standard practice.

Figure 1. Primary care provider opinions regarding who is most appropriate to provide prostate cancer survivorship care.

Pie chart representing responses from primary care providers who care for prostate cancer survivors in the State of Michigan to the following question: Do you feel it is appropriate for you to provide care related to the prostate cancer and/ or treatment complications or do you feel it is more appropriate for the treating physician to take care of such issues?

DISCUSSION

Primary care providers play a significant role in prostate cancer survivorship care during and beyond treatment. Their comfort levels managing prostate cancer treatment side effects varied in our study, with most being only somewhat comfortable treating common treatment sequelae regardless of provider type. This may relate to the fact that communication, planning, and treatment recommendations from the treating specialists were limited, especially regarding side effect management. Although the vast majority of primary care providers did inquire about treatment-related symptoms, systematic approaches to evaluating urinary and sexual symptoms using validated measures were scant. On average, primary care providers believe they are appropriate caregivers for prostate cancer survivors. Because more men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer as the population ages,10 primary care providers may need to increasingly participate in survivorship care.11

Providing quality prostate cancer survivorship care involves adequate monitoring for recurrent disease, effectively treating any side effects following the diagnosis, and promoting a healthy lifestyle.11 Respondents indicated that they understood the basic oncologic principle of prostate cancer surveillance by near universal referral to treating specialists in the setting of a rising PSA (a marker of disease recurrence and progression following treatment). However, this survey did not inquire about what providers believed was an appropriate threshold PSA level consistent with disease progression after treatment. Further study is needed to understand whether primary care providers understand the expected PSA levels following definitive therapy (i.e., undetectable after surgery; declining levels to a nadir after radiation). These findings would have important implications as early salvage therapy can be associated with improved survival.12

Although confidence in their treatments varied, primary care providers commonly used anticholinergics and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors to treat survivors’ incontinence and impotence, respectively. These are acceptable treatments in most cases; however, primary care providers also made frequent referrals to urologists to further investigate such symptoms. Urologist referral for commonly encountered, relatively straightforward side effects appeared to be excessive, perhaps indicating that primary care providers need more guidance to care for prostate cancer survivors. In addition, most providers reported that they did not use validated instruments to understand whether their treatments were successful. Easily administered surveys such as the Incontinence Symptom Index13 and the International Index of Erectile Function14 to track progress before and during treatment would allow providers to better understand how survivors’ symptoms are being managed. These are commonly used in urologic practice and might also inform the communication gap noted by providers in this study with respect to survivorship care. Finally, primary care providers are probably the best suited specialty to promote healthy lifestyles for prostate cancer survivors. Overall, they are well-positioned to provide quality prostate cancer survivorship care, but may need further direction from treating specialist physicians.

Underlying these findings is the absence of prostate cancer clinical practice guidelines and survivorship care plans to guide primary care providers caring for prostate cancer survivors. Primary care providers indicate that with appropriate information, guidance and efficient processes in place for re-referral and investigation of potential recurrences they would be able to assume greater responsibility for cancer survivorship care.15 The Institute of Medicine's landmark report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition notes the fundamental need for survivorship care plans and improved care coordination to improve the quality of cancer care.16 Highlighted in such a plan would be a summary of the critical information needed for the survivor's long-term care. For example, the cancer type and treatment, treatment-related side effects and their management, information regarding surveillance (i.e., PSA testing), and survey instruments to monitor urinary and sexual symptoms. Last, accountability for various aspects of survivorship care would also be outlined.16

Communicating survivorship care plans may improve survivorship quality of care among primary care providers through addressing the gaps identified in this study. In response to the findings of this survey and to improve the transfer of care from specialty to primary care, the Michigan Cancer Consortium Prostate Cancer Action Committee created guidelines for primary care physicians to help them manage prostate cancer treatment sequelae (http://www.michigancancer.org/PDFs/MCCGuidelines-PrimaryCareMgtProstateCaPost-TxSequelae.pdf).17 These publically available survivorship management guidelines may be especially important given that providers reported little interest in comprehensive survivorship clinics for their prostate cancer patients. For example, the incontinence portion of the guidelines provides a list of patient self-management strategies (e.g., monitoring fluid intake, weight loss), medical therapies (e.g., anticholinergics, Kegel exercises and pelvic floor physical therapy) as well as surgical options necessitating urologist referral (e.g., bulking agents, urethral sling) to help providers manage incontinence following surgery or radiation therapy. Better understanding how best to incorporate these guidelines into practice is needed. Support from the Society of Urologic Oncology, American Urological Association, the American Cancer Society and the American Society for Radiation Oncology for better education of primary care providers (including nurse practitioners and physician assistants) might improve the co-management of prostate cancer patients during and after definitive care.

The results of this study are from primary care providers in the State of Michigan, not a national sample. Nonetheless, we did include physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants to increase the generalizability of the findings. In addition, it is unlikely that primary care providers in Michigan are fundamentally different than those from other states. Next, the data are based on the self reported beliefs and practice patterns of primary care providers, not necessarily the survivorship care that patients actually receive. However, to the extent that attitudes and beliefs contribute to provider behavior, we would expect that improving various aspects of prostate cancer survivorship care in Michigan is warranted.18 The response rate of this study is insufficient to generalize with confidence due to possible selection bias, although not entirely uncommon for a physician survey.19 On the other hand, the degree of varying opinions and comfort levels among this sample of over 600 primary care providers treating prostate cancer survivors is unlikely to diminish with a larger sample size. Moreover, these data suggest that a substantial proportion of primary care providers may be prepared to assume primary responsibility and would welcome guidance regarding survivorship care. Whether the primary care workforce could tolerate the increased workload is unclear; however, it appears that many are already dealing with prostate cancer survivor issues. Given the lack of current resources to direct prostate cancer survivorship care, more education for both the urologic and primary care community seems warranted.

Primary care providers reported that prostate cancer survivorship care is prevalent in their practice. Since nearly all believed the specialist remained the primary treating physician, the primary care role appears to be an adjunct to specialty care early in survivorship. To improve quality of care and coordination, one option would be to implement prostate cancer survivorship care plans across specialties. An alternative is to transfer responsibility for prostate cancer survivorship care to the portion of primary care providers who express comfort with primary responsibility. Good communication with treating specialists, the use of existing standardized assessment tools and post-treatment guidelines or care plans may lead to improved quality of care for men with prostate cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank all of the primary care providers who participated in this survey to better understand prostate cancer care.

The 2006 Early Detection and Screening for Prostate and Colorectal Cancer Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice (KAP) Survey was implemented by the Michigan Public Health Institute, Cancer Control Services Program, and supported by Michigan Department of Community Health and Michigan Cancer Consortium, with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Cooperative Agreement 5U58DP000812

Dr. Skolarus is supported by an NIH T32 training grant (NIH 2 T32 DK007782-06), the American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, the American Urological Association North Central Section and the American Urological Association Foundation Research Scholar Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.Ries LAGMD, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb DG, Howlader N, Horner MJ, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Altekruse SF, Lewis DR, Clegg L, Eisner MP, Reichman M, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD: 2008. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/, based on November 2007 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roehrig C, Miller G, Lake C, Bryant J. National health spending by medical condition, 1996-2005. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w358–67. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [8-24-2009];Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. http://www.seer.cancer.gov/.

- 4.Gore JL, Kwan L, Lee SP, Reiter RE, Litwin MS. Survivorship beyond convalescence: 48-month quality-of-life outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:888–92. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, Cook EF, Earle CC. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2489–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ercolano E. Follow up of men post-prostatectomy: who is responsible? Urologic Nursing. 2008;28:370–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saultz JW, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:445–51. doi: 10.1370/afm.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yabroff KR, Davis WW, Lamont EB, Fahey A, Topor M, Brown ML, Warren JL. Patient time costs associated with cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:14–23. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. [2/18/2008];Early Detection and Screening for Prostate and Colorectal Cancer: Results from the Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice (KAP) Survey. A Michigan Cancer Consortium project coordinated by the Michigan Public Health Institute for the Michigan Department of Community Health. http://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/ProstColoCas-KAPSurvey-021808_266245_7.pdf.

- 10.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganz PA. Survivorship: adult cancer survivors. Prim Care. 2009;36:721–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trock B, Han M, Freedland S, Humphreys E, DeWeese T, Partin A, Walsh P. Prostate cancer-specific survival following salvage radiotherapy vs observation in men with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2008;299:2760–2769. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Hoag L, Faerber GJ, Dorr R, McGuire EJ. The Incontinence Symptom Index (ISI): a novel and practical symptom score for the evaluation of urinary incontinence severity. J Urol, suppl. 2003;169:33. abstract 128. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Pena BM. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, Piliotis E, Verma S. Primary care physicians' views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3338–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hewitt Maria, Greenfield Sheldon, Stovall Ellen., editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: LOST IN TRANSITION, Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life, National Cancer Policy Board. INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE AND NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michigan Cancer Consortium Prostate Cancer Action Committee [3/18/2010];Guidelines for Primary Care Management of Prostate Cancer Post-Treatment Sequelae. Available at http://www.michigancancer.org/PDFs/MCCGuidelines-PrimaryCareMgtProstateCaPost-TxSequelae.pdf.

- 18.Sheppard BH, Hartwick J, Warshaw PR. The Theory of Reasoned Action - a Meta-Analysis of Past Research with Recommendations for Modifications and Future-Research. Journal of Consumer Research. 1988;15:325–343. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–36. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]