Abstract

Background

Sex differences in methamphetamine (METH) use (females>males) have been demonstrated in clinical and preclinical studies. This experiment investigated the effect of sex on the reinstatement of METH-seeking behavior in rats and to determine whether pharmacological interventions for METH-seeking behavior vary by sex. Treatment drugs were modafinil (MOD), an analeptic, and allopregnanolone (ALLO), a neuroactive steroid and progesterone metabolite.

Method

Male and female rats were trained to self-administer i.v. infusions of METH (0.05mg/kg/infusion). Next, rats self-administered METH for a 10-day maintenance period. METH was then replaced with saline, and rats extinguished lever-pressing behavior over 18 days. A multi-component reinstatement procedure followed where priming injections of METH (1 mg/kg) were administered at the start of each daily session, preceded 30 min by MOD (128 mg/kg, i.p.), ALLO (15 mg/kg, s.c.), or vehicle treatment. MOD was also administered at the onset of the session to determine if it would induce the reinstatement of METH-seeking behavior.

Results

Female rats had greater METH-induced reinstatement responding compared to male rats following control treatment injections. MOD (compared to the DMSO control) attenuated METH-seeking behavior in male and female rats; however, ALLO only reduced METH-primed responding in females. MOD alone did not induce the reinstatement of METH-seeking behavior.

Conclusions

These results support previous findings that females are more susceptible to stimulant abuse compared to males and ALLO effectively reduced METH-primed reinstatement in females. Further, they illustrate the utility of MOD as a potential agent for prevention of relapse to METH use in both males and females.

Keywords: Allopregnanolone, Methamphetamine, Modafinil, Rats, Reinstatement, Sex differences

1. Introduction

While fewer females currently use methamphetamine (METH) than males (SAMHSA 2009), females initiate METH use at earlier ages and display more acute dependence (for review, see Dluzen and Liu, 2008). Results from animal studies reflect this pattern, showing that female rats are more sensitive to METH-induced locomotor activity (Milesi-Halle et al., 2007; Schindler et al., 2002), acquire METH self administration at faster rates, and administer greater amounts of METH under fixed- and progressive-ratio schedules of reinforcement (Roth and Carroll, 2004a). While female rats are more prone to stimulant use, they may also be more receptive to pharmacological treatment interventions. For example, Cosgrove et al. (2004) found that female rhesus monkeys showed a greater decrease in oral phencyclidine self administration following bremazocine, and Campbell et al. (2002) showed that baclofen, a GABAB agonist that has been investigated as a treatment for stimulant addiction (Roberts, 2005), was more effective at attenuating rates of acquisition of cocaine self-administration in female rats compared to males. Further, a kappa opioid agonist was more effective at reducing cocaine-induced locomotor activity in female mice compare to male mice (Sershen et al., 1998). While these studies suggest greater treatment receptivity for females, the differential treatment of stimulant abuse with agonist replacements has not been studied during relapse with males vs. females.

Agonist-based treatment is an emerging strategy for stimulant addiction (Hart et al., 2008; Herin et al., 2010, but see Castells et al. 2010). Modafinil (MOD) is an agent of this type and is currently being investigated as treatment for stimulant abuse (Martinez-Raga et al., 2008). Research with non-human primates has indicated that MOD was effective at reducing cocaine-maintained responding (Newman et al., 2010). Further, results from a recent clinical trial indicate that MOD treatment was correlated with increased periods of abstinence in cocaine addicts with comorbid alcohol dependence (Anderson et al., 2009). This finding was supported by an experiment that used a preclinical model of relapse (Reichel and See, 2010) in which MOD was effective at attenuating the reinstatement of METH-seeking behavior in male rats following conditioned cues and drug-priming injections.

Given the sex-differences in treatment response found in previous studies (Campbell et al., 2002; Cosgrove and Carroll, 2004; Sershen et al., 1998) and the exclusive use of male rats in Reichel and See (2010), one aim of the present study was to investigate the possible differential effects of MOD on the reinstatement of METH-seeking behavior between male and female rats. Additionally, growing literature is implicating the role of circulating gonadal hormones in the sex differences observed in substance abuse behaviors (for reviews, see Anker and Carroll, 2010; Carroll and Anker, 2010; Lynch et al., 2002). Increased risk for stimulant abuse in females has been associated with higher levels of estrogen (Segarra et al., 2010), while these effects are attenuated by the progesterone metabolite and positive GABAA receptor modulator allopregnanolone (ALLO; Anker and Carroll, 2010). Indeed, ALLO administration attenuated the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in female, but not male rats (Anker et al., 2009). Thus, a second aim was to investigate the effects of ALLO on the reinstatement of METH-seeking behavior in male and female rats. As female rats respond more during reinstatement following cocaine-priming injections (Anker et al., 2009), the final aim was to investigate sex differences during METH-primed reinstatement.

In the present experiment male and female rats self-administered i.v. infusions of METH and then drug-seeking behavior was extinguished. Subsequently, rats were tested on a multi-component reinstatement procedure in which they received METH priming injections preceded by ALLO, MOD, or control treatments. Since MOD enhances and ALLO inhibits dopamine transmission, both treatments were examined within-subjects to compare potentially sex-mediated effects of these distinct pharmacological approaches to relapse prevention.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Male (n = 10) and female (n = 9) Wistar rats (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) weighing 350–400 g and 250–300 g, respectively, were used in the present study. Estrous cycle was allowed to vary randomly in females so that the effects of fluctuating hormones on drug-seeking behavior would generalize to female rats regardless of cycle phase. Rats were pair-housed in plastic cages upon arrival in the laboratory, and they had ad libitum access to food and water. Next, chronic, indwelling catheters were implanted in the jugular vein as previously described in Carroll and Boe (1982). After they recovered from surgery, rats were placed in operant conditioning chambers where they remained for the duration of the study. Throughout the experiment, they were given free access to water and 20 g (males) or 16 g (females) of ground food per day. Rats were housed under a constant light/dark cycle (12/12-h with room lights on at 6:00 am) in humidity- and temperature- (24° C) controlled holding rooms. The experimental protocol (1008A87755) was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and the experiment was conducted in accordance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (National Research Council, 2003) in laboratory facilities accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

2.2. Self-administration, extinction, and reinstatement

The drug self-administration apparatus was identical to that described by (Roth and Carroll, 2004b). Briefly, operant chambers were stainless steel and octagon-shaped. They contained a drinking spout, recessed food receptacle, 2 stimulus lights, one active and one inactive lever, and a house light. During self-administration sessions the house light was illuminated, and a response on the active lever resulted in the delivery of an i.v. infusion of METH and activated the stimulus lights above the lever for the length of the infusion. Responses on the inactive lever illuminated the stimulus light above the lever but did not result in an infusion. Initially, rats were trained to lever press for i.v. infusions of METH (0.05 mg/kg/infusion) during 6-h daily sessions (9:00 am to 3:00 pm). Sessions ended at 3:00 pm or when rats achieved 40 infusions, whichever came first. Once they self-administered 40 infusions for 3 consecutive days, rats continued responding for METH during 2-h daily sessions (9:00 am to 11:00 am) for 10 days, but infusions were unlimited. Next, METH was replaced with saline, and rats extinguished lever responding for a period of 18 days. The house light, stimulus lights and drug infusion pump were unplugged one day prior to the reinstatement procedure and remained unplugged for the remainder of the experiment. During reinstatement, control treatments for ALLO (15 mg/kg, s.c.) and MOD (128 mg/kg, i.p.) were peanut oil (V, s.c.) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, i.p.), respectively. These treatments were administered 30 min before a METH (1 mg/kg, i.p.) priming injection that was given at the onset of session. Additionally, MOD and DMSO priming injections were administered alone at the beginning of the session to determine if MOD induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. The following is an example of the range of the 6 conditions in the reinstatement procedure; however, priming conditions were randomized across rats to counter possible ordering effects: V+METH, ALLO+METH, DMSO+METH, MOD+METH, DMSO, MOD. Each of these conditions was preceded by a daily session that commenced with a saline-priming injection (S).

2.3. Drugs

d-Methamphetamine HCL (METH) was supplied by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) and was dissolved in sterile 0.9% NaCl saline at a concentration of 0.2 mg METH/mL saline and refrigerated. ALLO was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and was dissolved in peanut oil (20 mg allopregnanolone/mL peanut oil). MOD was synthesized in the laboratory of Dr. T. E. Prisinzano (Department of Medicinal Chemistry, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS) and dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 100 mg MOD/mL DMSO.

2.4. Data analysis

Active and inactive responses and infusions during maintenance and extinction, as well as active and inactive responses made during reinstatement, served as dependent measures. Responses and infusions were averaged across two 5-day blocks for the 10-day maintenance phase, and two 9-day blocks during the 18-day extinction phase. Between-group comparisons of active and inactive responses and infusions during maintenance and extinction were analyzed using a 2-factor repeated-measures ANOVA. Between-group comparisons of responses during reinstatement were analyzed separately with 2-factor repeated-measures ANOVAs, as shown in the separate panels in Fig. 2. Inactive lever pressing during reinstatement was similarly analyzed. Post-hoc comparisons were made between group means using Fischer’s LSD protected t-tests.

Fig. 2.

Mean (±SEM) number of responses made on the lever previously drug-paired lever during all three components of the reinstatement condition. The @ symbol represents significant within-subject decrease between D+METH and MOD+METH as well as V+METH and A+METH. The * indicates a within-subject decrease in responding when comparing sessions with pretreatments and METH priming injections to sessions with S. The # indicates that females showed greater reinstatement responding compared to males for the D+METH and V+METH conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Maintenance and Extinction

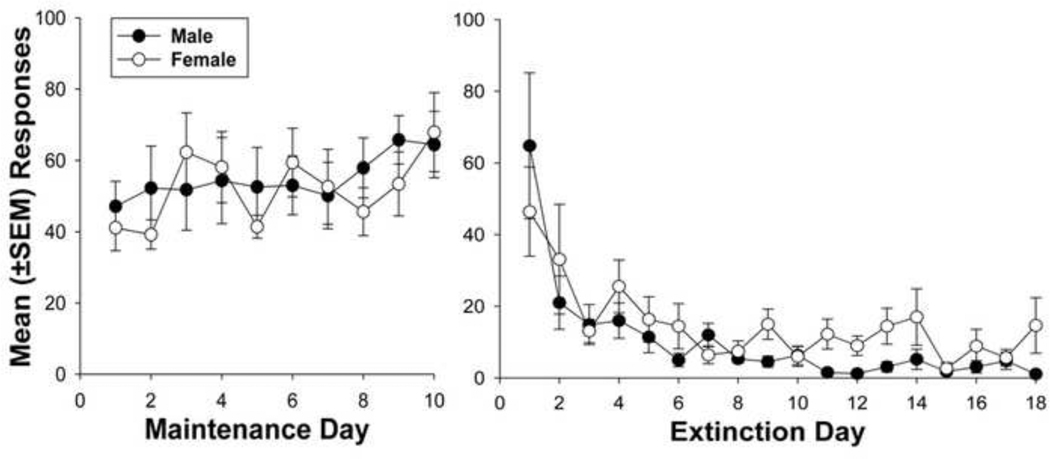

As shown in Fig. 1, there were no significant differences between males and females in active lever pressing throughout the maintenance [mean (±SEM) males = 53.3 (±4.4), females = 52.0 (±3.0)] or extinction [mean (±SEM) males 11.3 (±1.6), females = 15.0 (±1.8)] phases. Responding was stable throughout the maintenance phase for both groups. In both groups, responding declined over the first 6 extinction sessions and remained at low and stable levels for the remaining 12 days. There were no significant differences in responses on the inactive lever during either phase.

Fig. 1.

Mean (±SEM) number of responses made for i.v. infusions of methamphetamine (0.05 mg/kg) on the active lever during maintenance (left) and mean responses made for saline during the extinction (right). There were no significant differences during these conditions.

3.2. Reinstatement

Fig. 2 shows mean responses on the lever previously associated with METH during the 3 components of the reinstatement procedure. For the MOD component, there were main effects for treatment (F2,32 = 36.99, p < 0.001) and sex (F1,36 = 12.40, p = .0028), as well as an interaction between these factors (F2,53 = 8.89. p < 0.001). Female rats showed higher responding following DMSO+METH compared to males (ps < 0.01), while both males and females responded more following DMSO+METH compared to MOD+METH and S conditions (males, ps < 0.05; females ps < 0.01). For the ALLO component, there were main effects for both treatment (F2,34 = 14.34, p < 0.001) and sex (F1,38=6.02, p=.025), as well as an interaction between sex and treatment (F2,56 = 5.69, p = 0.007). Female rats responded more than males following V+METH (ps < 0.05), and only females showed a reduction in responding when comparing V+METH to ALLO+METH (ps < 0.05). ALLO produced a 39% decrease in responding for females and 0% for males compared to V. Responses made by the female group following either the V+METH or ALLO+METH conditions (ps < 0.01) were greater than responses made by females during the S condition. However, males showed greater responding following ALLO+METH (ps < 0.05) compared to S, but no difference was found when comparing V+METH to S within this group. There were no significant differences in reinstatement responding generated by priming injections of MOD vs. priming injections of DMSO.

For inactive lever responses, there was a significant main effect for treatment (F2,32 = 25.47, p < 0.001) during the MOD component. Data were combined between males and females, and post hoc comparisons showed that inactive lever responses were higher following DMSO+METH compared to both MOD+METH (ps < 0.01) and S (ps < 0.01). There were no significant results for the ALLO or MOD vs. DMSO components.

4. Discussion

The present study showed that female rats exhibit greater reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior compared to males following METH-priming injections. This result supports previous research in which females showed more within- and between-session reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior than males (Anker et al., 2009; Lynch and Carroll, 2000), as well as clinical data indicating that females may be more prone to relapse to cocaine use than males (Robbins et al., 1999). Additionally, the results of the present study show that the attenuating effects of ALLO on female, but not male, cocaine-seeking behavior (Anker et al., 2009) generalize to METH-seeking behavior as well. MOD again blocked METH-induced reinstatement responding in male rats as shown by Reichel and See (2010), and the present study extended these findings to female rats.

Compared to the DMSO vehicle, MOD administration resulted in substantially reduced METHseeking behavior during reinstatement in both males (97%) and females (87%). In light of the previous study by Campbell et al. (2002) that indicated a sex-specific treatment reduction in cocaine acquisition for the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen (females>males), the current study lends support for agonist-based (vs. inhibitory, e.g., baclofen) treatment strategies for stimulant addition. The scope of MOD’ neurobiological actions remains unclear; however, it has been shown to affect different types of neurotransmitters through multiple mechanisms (Dackis and O'Brien, 2003; Ferraro et al., 1998). For instance, a recent study suggests that the effectiveness of MOD as a treatment for METH addiction may lie in its ability to both enhance synaptic dopamine levels and interfere with METH-induced dopamine increase through modulation of dopamine-transporter functioning (Andersen et al., 2010; Zolkowska et al., 2009). This dual action of MOD could partially account for its reduction in the METH-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in male and female rats shown in the present experiment. Additionally, since MOD failed to induce reinstatement, its dopamine-enhancing effects did not result in relapse liability, as has also been shown in the clinical literature (Anderson et al., 2009; Vosburg et al., 2010). Regardless of the nature of its specific pharmacological actions, the present study supports the efficacy of MOD as a possible agent to treat METH addiction.

While there were no sex-differences in the attenuating effects of MOD on METH-induced reinstatement responding, ALLO predictably reduced METH-primed reinstatement of drug seeking in females but not males. These results extended the potential treatment effects of ALLO on METH-induced reinstatement, but only in females. Anker et al (2009) found similar sex differences with cocaine reinstatement, and this differential action was attributed to the mediating effects of the circulating gonadal hormones estrogen and progesterone, as well as the progesterone metabolite ALLO. ALLO is a GABAA positive modulator that is thought to inhibit the enhancing effect of estrogen on cocaine-seeking behavior (Anker and Carroll, 2010). This putative effect of estrogen on cocaine-seeking behavior is illustrated by the greater reinstatement of responding after a METH-priming injection with vehicle pretreatment in females compared with males. While the present results further implicate gonadal hormones and their metabolites in the sex-differences found in addiction research, more work is needed to elucidate the mechanisms driving these differences. In addition to the present findings, past result suggest that investigating neurobiological differences in GABA functions between males and females may be of interest (Campbell et al., 2002; Febo and Segarra, 2004; Siegal and Dow-Edwards, 2009).

The reduction of inactive lever pressing by MOD following METH priming injections is likely due to MOS counteracting METH’s potentiation of hyperactivity. However, since all rats met a 2:1 ratio for active vs. inactive lever pressing ratio following the MOD+METH condition, active lever responding can be considered to be drug-seeking behavior. Further, Reichel and See (2010) found no effects of MOD on locomotor activity, and MOD administered alone had no impact on inactive lever pressing in the present experiment. Thus, it is improbable that MOD’s attenuation of METH-primed reinstatement responding is due to a general suppression of activity in the rats. ALLO had no effect on inactive lever pressing during reinstatement, and that agrees with previous research showing no effect of ALLO on locomotor activity or food-maintained lever pressing at a dose greater than that presently tested (Anker et al., 2009).

In summary, female rats showed higher METH-induced reinstatement responding than males, and MOD was effective in attenuating reinstatement responding in both males and females. ALLO, however, attenuated reinstatement in female but not male rats. Modafinil’s therapeutic potential was supported by the inability of MOD to serve as a priming event for METH-seeking behavior in both male and female rats. The present findings also underscore the importance of sex-specific treatment strategies for reducing relapse.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grants R01 DA018151S1 (TEP), R01 DA003240, R01 DA019942, K05 DA015267 (MEC). NIDA had no additional part in the study design; in data collection, analysis, or interpretation; in writing; nor in the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Justin Anker, Seth Johnson, Paul Regier, Tyler Rehbein, Amy Saykao, Rachael Turner and Natalie Zlebnik for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Nathan Holtz and Marilyn Carroll were involved in the experimental design, data analysis, graphic presentation, and manuscript preparation. Thomas Prisinzano and Anthony Lozama synthesized the modafinil used in this experiment and were involved in manuscript preparation. All authors were involved in the final preparation of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Andersen ML, Kessler E, Murnane KS, McClung JC, Tufik S, Howell LL. Dopamine transporter-related effects of modafinil in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2010;210:439–448. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1839-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AL, Reid MS, Li SH, Holmes T, Shemanski L, Slee A, Smith EV, Kahn R, Chiang N, Vocci F, Ciraulo D, Dackis C, Roache JD, Salloum IM, Somoza E, Urschel HC, 3rd, Elkashef AM. Modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Carroll ME. The role of progestins in the behavioral effects of cocaine and other drugs of abuse: human and animal research. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010;35:315–333. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Holtz NA, Zlebnik N, Carroll ME. Effects of allopregnanolone on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in male and female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2009;203:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell UC, Morgan AD, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the effects of baclofen on the acquisition of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Anker JJ. Sex differences and ovarian hormones in animal models of drug dependence. Horm. Behav. 2010;58:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Boe IN. Increased intravenous drug self-administration during deprivation of other reinforcers. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1982;17:563–567. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castells X, Casas M, Perez-Mana C, Roncero C, Vidal X, Capella D. Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007380.pub3. CD007380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME. Differential effects of bremazocine on oral phencyclidine (PCP) self-administration in male and female rhesus monkeys. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2004;12:111–117. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis C, O'Brien C. Glutamatergic agents for cocaine dependence. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;1003:328–345. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dluzen DE, Liu B. Gender differences in methamphetamine use and responses: a review. Gend. Med. 2008;5:24–35. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(08)80005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febo M, Segarra AC. Cocaine alters GABA(B)-mediated G-protein activation in the ventral tegmental area of female rats: modulation by estrogen. Synapse. 2004;54:30–36. doi: 10.1002/syn.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro L, Antonelli T, O'Connor WT, Tanganelli S, Rambert FA, Fuxe K. The effects of modafinil on striatal, pallidal and nigral GABA and glutamate release in the conscious rat: evidence for a preferential inhibition of striato-pallidal GABA transmission. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;253:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Vosburg SK, Rubin E, Foltin RW. Smoked cocaine self-administration is decreased by modafinil. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:761–768. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herin DV, Rush CR, Grabowski J. Agonist-like pharmacotherapy for stimulant dependence: preclinical, human laboratory, and clinical studies. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1187:76–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Carroll ME. Reinstatement of cocaine self-administration in rats: sex differences. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2000;148:196–200. doi: 10.1007/s002130050042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Roth ME, Carroll ME. Biological basis of sex differences in drug abuse: preclinical and clinical studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2002;164:121–137. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Raga J, Knecht C, Cepeda S. Modafinil: a useful medication for cocaine addiction? Review of the evidence from neuropharmacological, experimental and clinical studies. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:213–221. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801020213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milesi-Halle A, McMillan DE, Laurenzana EM, Byrnes-Blake KA, Owens SM. Sex differences in (+)-amphetamine- and (+)-methamphetamine-induced behavioral response in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007;86:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JL, Negus SS, Lozama A, Prisinzano TE, Mello NK. Behavioral evaluation of modafinil and the abuse-related effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010;18:395–408. doi: 10.1037/a0021042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, See RE. Modafinil effects on reinstatement of methamphetamine seeking in a rat model of relapse. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2010;210:337–346. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1828-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins SJ, Ehrman RN, Childress AR, O'Brien CP. Comparing levels of cocaine cue reactivity in male and female outpatients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;53:223–230. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC. Preclinical evidence for GABAB agonists as a pharmacotherapy for cocaine addiction. Physiol. Behav. 2005;86:18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth ME, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the acquisition of IV methamphetamine self-administration and subsequent maintenance under a progressive ratio schedule in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2004a;172:443–449. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth ME, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the escalation of intravenous cocaine intake following long- or short-access to cocaine self-administration. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2004b;78:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Bross JG, Thorndike EB. Gender differences in the behavioral effects of methamphetamine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;442:231–235. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarra AC, Agosto-Rivera JL, Febo M, Lugo-Escobar N, Menendez-Delmestre R, Puig-Ramos A, Torres-Diaz YM. Estradiol: a key biological substrate mediating the response to cocaine in female rats. Horm. Behav. 2010;58:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sershen H, Hashim A, Lajtha A. Gender differences in kappa-opioid modulation of cocaine-induced behavior and NMDA-evoked dopamine release. Brain Res. 1998;801:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal N, Dow-Edwards D. Isoflurane anesthesia interferes with the expression of cocaine-induced sensitization in female rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;464:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.07.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosburg SK, Hart CL, Haney M, Rubin E, Foltin RW. Modafinil does not serve as a reinforcer in cocaine abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;106:233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolkowska D, Jain R, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Roth BL, Setola V, Prisinzano TE, Baumann MH. Evidence for the involvement of dopamine transporters in behavioral stimulant effects of modafinil. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;329:738–746. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.146142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]