Abstract

Giardia, a flagellated protozoan that infects the upper small intestine of its vertebrate host, is the most common parasitic protist responsible for diarrhea worldwide. Molecules released by the parasite, particularly excretory and secretory antigens, seemed to be associated with pathogenesis as well as with the expression of Giardia virulence. In the present work, we examined the effect of oral administration of Giardia intestinalis excretory and secretory antigens on systemic and local antibody response as well as on mucosal injuries in BALB/c mice. Significant titers of serum-specific immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and specific IgG2a were observed. Systemic and mucosal specific IgA antibodies were also recorded. A transient production of serum-specific IgE antibody and high total IgE levels were also detected, suggesting the presence in excretory and secretory proteins of factors promoting a specific IgE response. The sera of excretory and secretory antigen-treated mice recognized proteins of 50 and 58 kDa as well as electrophoretic bands of 15, 63, and 72 kDa that could support a proteinase activity. The in vitro exposure of G. intestinalis trophozoites to heat-inactivated sera from mice orally inoculated with excretory and secretory antigens induced a decrease of growth, revealing a complement-independent inhibitory activity of specific serum antibodies. Furthermore, histological evaluation performed on the small and large intestines revealed moderate to acute histological changes comparable to those observed in natural or experimental Giardia infection characterized by eosinophilic infiltration, hypercellularity, and enterocytic desquamation. The present results suggested that Giardia excretory and secretory antigens stimulate a preferential Th2 response, which is probably involved in the intestinal alterations associated with giardiasis.

Giardia intestinalis (synonymous with Giardia lamblia and Giardia duodenalis) is a common causative agent of diarrhea disease occurring in humans and various mammal species (1). This parasite has a worldwide distribution, and its prevalence varies from 15 to 30% in developing countries (26). The infection has been shown to be more prevalent in children less than 3 years of age as well as in undernourished and immunocompromised hosts (5). Moreover, previous studies have also showed that Giardia infection induces a mucosal immune response to other allergens (13) and may be related to an increased incidence of urticaria and food allergies (10). The pathogenesis of giardiasis is not clearly understood, but villous atrophy and reduction of the absorptive area of the small intestine have been reported, which result from a brush border enzyme deficiency responsible for malabsorption (6). Studies in vitro and in vivo have suggested that the parasite is able to produce toxin(s) (3, 8), but the factors inducing mucosal alterations in Giardia infection have not been identified yet, and at this point they are still controversial (12). It has been suggested that excretory and secretory (E/S) antigens (Ags) may play a role in giardial pathogenesis. In the same way, Meyer and Radulescu (31) argued that E/S Ags released by the parasite are responsible for diarrhea. Studies of parasite lysates have demonstrated that G. intestinalis trophozoites contain proteins with proteolytic activity (16, 51) which might be involved in parasite biology (47). In this context, we recently identified E/S Ag products with proteolytic activity in trophozoites of G. intestinalis incubated in a protein-free medium (19). However, the potential role of these molecules in the immune response and intestinal pathophysiology remain unclear. Thus, the hypothesis that E/S Ags from G. intestinalis would promote the immune response and participate in mucosal injuries through the immune response that they elicit is of major interest. The goal of the present work was to determine whether the oral administration of G. intestinalis E/S Ags is able to induce specific systemic or local responses and to reproduce the histological alterations observed in giardiasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite culture and E/S Ag preparation.

G. intestinalis trophozoites of the P1 strain (American Type Culture Collection no. 30888) were cultured axenically in filter-sterilized TYI-S-33 medium (22) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y.) for 48 to 72 h at 37°C in 15-ml glass culture tubes. E/S Ags were obtained in culture medium as described by Guy et al. (15). Briefly, culture tubes were rinsed with RPMI 1640 medium at 37°C to remove nonattached or dead trophozoites. Then RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with glutamine (2 mM) and l-cysteine (11.4 mM) was added, and cultures were incubated for 6 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. After incubation, culture tubes were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. Supernatants were concentrated threefold on Aquacide II (Calbiochem, Meudon, France), filtered through a MILLEX-GS filter (0.22-μm pore size; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until use.

Detection of proteolytic activity in G. intestinalis E/S Ags.

The proteolytic activity of E/S Ags was detected on sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-10% PAGE) gels copolymerized with 0.1% (wt/vol) gelatin (27). Electrophoresis (50 μg of protein/well) was conducted for 1 h at 4°C in a Miniprotein II apparatus (Bio-Rad) at 30 mA with a Tris-glycine buffer system. To remove SDS, gels were incubated in 2% Triton X-100 solution in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) for 30 min at 4°C, washed three times with distilled water for 10 min and incubated with a 0.1 M Tris-HCl solution (pH 8.0) for 30 min at 4°C. Finally, gels were incubated overnight at 37°C in 50 ml of citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 50 mM l-cysteine and 2.5 mM CaCl2. Thereafter, gels were stained with Coomassie blue R-15 prepared in 15% methanol, 10% acetic acid, and 1% glycerol. Proteinase molecular weight was evaluated by comparison to protein markers (Bench Mark prestained protein ladder).

Mice and immunization procedures.

Female BALB/c mice (6 to 8 weeks old at the beginning of the study) were purchased from IFFA-CREDO (L'Arbresle, France). Mice were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Groups of 10 mice were orally administered G. intestinalis E/S Ags (250 μg/mouse, without adjuvant) weekly for 21 weeks, and 10 mice of the each group received either phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or 250 μg of ovalbumin (OVA)/mouse orally in the same manner. Before oral administration, stomach acidity was neutralized with 0.25 ml of NaHCO3 aqueous solution (100 mg/ml, pH 8.5). Henceforth, mice administered E/S Ags are called E/S mice, those that received PBS are called control mice, and those orally immunized with OVA are called OVA mice.

Animal experiments were performed according to the conditions stipulated in European guidelines (Council directives on the protection of animals for experimental and others scientific purposes, 86/609/EEC, J. Off. Communautés Européennes, 86/609/EEC, 18 December 1986, L358).

Serum and fecal sampling.

Blood or fecal sampling of individual animals began (day 0) before the oral administration of E/S products, PBS, and OVA to E/S, control, and OVA mice, respectively, and was pursued for 158 days at variable intervals. E/S, control, and OVA mice were bled by retro-orbital plexus puncture, and sera were recovered and stored at −20°C. For specific intestinal immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibody determination, fecal extracts were prepared as follows. Four to five fecal pellets of each mouse were incubated in reweighed Eppendorf tubes containing protease inhibitors in PBS at 4°C for 1 h. Tubes were then vortexed and centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 rpm at 4°C to remove insoluble material. Supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until use.

Antibody detection.

Antibodies were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (39). Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates (Nunc-Immuno Plate Maxi Sorp; Nalge Nunc Int., Roskilde, Denmark) were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μl of 10-μg/ml E/S Ags diluted in PBS (pH 7.4)/well. After 2 washes with PBS-0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma) (PBS-T), plates were saturated for 1 h with 0.5% gelatin-PBS solution (250 μl/well). After two washes, sera were diluted in PBS-T (1:100 for IgG1 and IgG2a and 1:10 for IgA and IgE), added to the plates in duplicate series, and incubated overnight at 4°C. Anti-E/S Ag antibody levels were evaluated by using a specific goat horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse isotype (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, Ala.) diluted in PBS-T (1:5,000 for IgG1 and IgA and 1:10,000 for IgG2a), and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. For specific anti-E/S Ag IgE, sera were diluted 1:10 and incubated overnight at 4°C. Then, after 3 washes with PBS-T, biotinylated rat anti-mouse IgE antibody (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) diluted 1:7,500 was added to the plates and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After 5 washes, 100 μl of streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate (Amersham, Orsay, France)/well diluted at 1:2,000 was added and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The reactions were revealed with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine peroxidase substrate (TMB) (100 μl/well; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) for 20 min. Finally, the reaction was stopped with 2 N HCl solution (100 μl/well), and the optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm on a Titertek Multiskan apparatus (Mcc 1340; Labsystems). The results were expressed as titers of serum antibody, defined as the log of dilution that generated an OD equal to two standard deviations (SD) above the mean background OD of control mouse sera at 450 nm. Fecal specific IgA levels were determined in nondiluted extract samples and were expressed as means ± SD of OD values from 10 mice. Parallel testing of sera from OVA mice against E/S Ags validated the specificity of ELISA. Likewise, ELISAs against OVA used as an Ag allowed checking of the specificity of the anti-E/S Ag antibody response of E/S mice.

Determination of total serum IgE.

Total IgE concentrations were evaluated on plates coated overnight at 4°C with the rat monoclonal antibody anti-mouse IgE (2 μg/ml, clone R35-72; PharMingen) in carbonate buffer (100 μl/well, pH 9.6). After blocking with a 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and 2 washes with PBS-T, 100 μl of serial dilutions of mouse IgE standard (anti-TNP; PharMingen)/well and 100 μl of diluted serum samples (1:50 in PBS-T-1% BSA)/well were incubated overnight at 4°C. After five washes, 100 μl of biotinylated rat anti-mouse IgE (2 μg/ml; Southern Biotechnology)/well was added and incubated for 90 min at 37°C. Streptavidin-HRP (1:2,000; Amersham) was added. Plates were then incubated for 30 min at 37°C and treated as described above for antibody detection. Sample OD values were converted to micrograms of IgE per milliliter by reference to the standard curve. The detection threshold was 6 ng/ml.

Immunoblotting.

Proteins were run in SDS-10% PAGE gels under reducing conditions without boiling (24) and electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (48) (0.45-μm-pore-size NC membrane; Schleicher & Schuell Keene, Dassel, Germany) for 90 min at 125 mA with a Bio-Rad Miniprotein II apparatus. Membranes were blocked with a 5% nonfat milk solution in PBS for 2 h at room temperature and washed three times with PBS-T. Membranes were cut in strips, incubated with pooled sera diluted in PBS-T containing 1% nonfat milk (1:100 for IgG1 and IgG2a and 1:25 for IgA), and incubated overnight at 4°C under agitation. The strips were washed five times with PBS-T and incubated with goat HRP-conjugated anti-mouse serum for each isotype diluted in PBS-T (1:1,000 for IgG1 and IgG2a and 1:250 for IgA) for 90 min at 37°C. For identification of specific IgE Ags, pooled sera of mice were diluted (1:25) in PBS-T containing 1% nonfat milk overnight at 4°C. After five washes (with PBS-T), the strips were incubated with biotinylated rat anti-mouse IgE (Southern Biotechnology) diluted in PBS-T at 1:250 for 90 min at 37°C. Streptavidin-HRP conjugate (1:500) was added and incubated for 60 min at 37°C. Finally, immune reactive proteins were revealed by using a diaminobenzidine (DAB) kit (Novo Castra).

Parasite growth inhibition assay.

To evaluate the functional activity of anti-E/S Ag serum antibodies from mice orally inoculated with E/S products, the ability of trophozoites to grow in fresh culture medium after exposure to sera from E/S mice was tested as described by Hemphill et al. (17). Briefly, trophozoites developing in 5-ml screw-cap culture vials until late logarithmic phase were rinsed once with 5 ml of PBS at 37°C to remove nonviable or nonadherent parasites. Viable trophozoites were dislodged in cold PBS, centrifuged, and resuspended in TYI-S-33 medium at a concentration of 6 × 106 cells/ml. Then, 10 μl of this suspension (6 × 104 cells/ml) was distributed into the wells (100 μl/well) of a round-bottom microtiter plate (Nunc) and incubated (1 h at 37°C in 5% CO2) in 100 μl of heat-inactivated pooled sera diluted 1:20 in PBS (collected at days 7, 42, 88, 135, and 158) from E/S, control, or OVA mice. After incubation, 10 μl of parasite suspension from each well was subcultivated in TYI-S-33 medium at 37°C for 24 or 48 h. Finally, adherent parasites were dislodged in ice for 10 min, and 10 μl of this suspension was used for parasite counting in a Neubauer cell counter chamber. Results were expressed as means ± SD of parasite counts, and they were compared with parasites exposed to pooled sera from control or OVA mice in three separate experiments.

Histological evaluation.

For the assessment of pathological alterations, small and large intestine samples from each mouse were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in histowax. Tissues were cut into sections of 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin-eosin for assaying the histological changes or May-Grünwald-Giemsa for eosinophilic cell detection. At least 4 to 5 random sections per intestinal portion (small intestine or colon) and per mouse were examined. Eosinophil numbers were determined in each section in the duodenum and ileum by counting randomly from the base to the tip of 20 villi per mouse. The results were expressed as means ± SD of the number of eosinophils per villus-crypt units (VCU) (29).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical differences in serum and fecal IgA antibody levels were determined between groups of mice by using a one-tailed Student's test with StatView software (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, Calif.). P values under 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Identification of G. intestinalis E/S Ags with proteolytic activity.

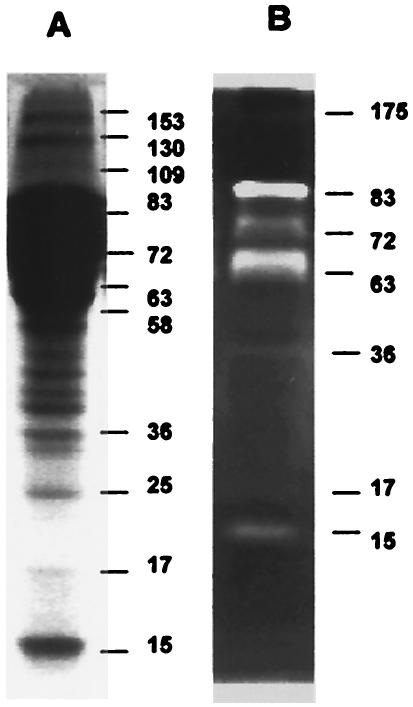

Electrophoresis analysis of E/S Ags revealed a complex pattern of at least 11 bands corresponding to molecules from 15 to 153 kDa (Fig. 1A). The zymographic analysis revealed a gelatinase activity in seven bands (15, 17, 36, 63, 72, 83, and 175 kDa) (Fig. 1B; see also Fig. 5). Most intense proteolytic signals were located at bands of 63 and 83 kDa. The positions of the proteins were different in the electrophoretic profile and in the zymographic pattern because the substrate-copolymerized acrylamide gels usually induce a decrease in protein mobility (Fig. 1), as was reported previously (18).

FIG. 1.

Electrophoretic profile and gelatinolytic activity of G. intestinalis E/S Ags. (A) SDS-PAGE showing bands of 15 to 153 kDa; (B) zymographic analysis showing 15- to 83-kDa bands with proteolytic activity (whitened zones). The gels were stained with Coomassie blue. Molecular sizes are given in kilodaltons to the right of the lanes.

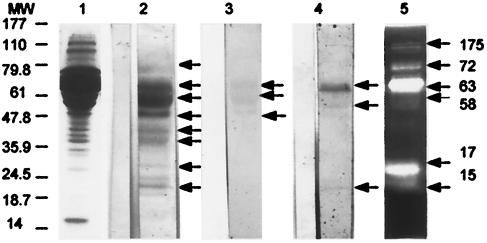

FIG. 5.

Serum reactivity of BALB/c mice orally immunized with Giardia E/S Ags evaluated by Western blotting. Mouse sera were sampled 96 days after oral immunization with Giardia E/S Ags. Each lane contains 50 μg of Giardia E/S products. Immunoblotted proteins were probed with pooled sera from 10 mice diluted 1:100 (IgG1 antibody) (lane 2), 1:25 (IgA antibody) (lane 3), or 1:25 (IgE antibody) (lane 4). Antibody binding for IgG1 and IgA was detected with a goat HRP-conjugated anti-isotype antibody, whereas IgE antibody was detected with biotinylated rat anti-mouse IgE antibody. Bands of 15, 17, 36, 42, 50, 58, 63, and 72 kDa were recognized by serum IgG1 antibody (lane 2). Serum IgA antibody recognized proteins of 50, 58, and 63 kDa (lane 3), and serum IgE antibody recognized proteins of 15, 58, and 63 kDa (lane 4). Sera of pooled mice which have received PBS (control mice) are shown on the left side of each lane. Lane 5 shows gelatinase activity of E/S Ags as revealed in an SDS-10% PAGE gel copolymerized with 0.1% (wt/vol) gelatin. A proteolytic activity is visible in bands of 15, 17, 58, 63, 72, and 175 kDa. Molecular sizes are indicated in kilodaltons on the left side of the picture.

Isotype profiles of specific serum antibody in BALB/c mice orally immunized with G. intestinalis E/S Ags.

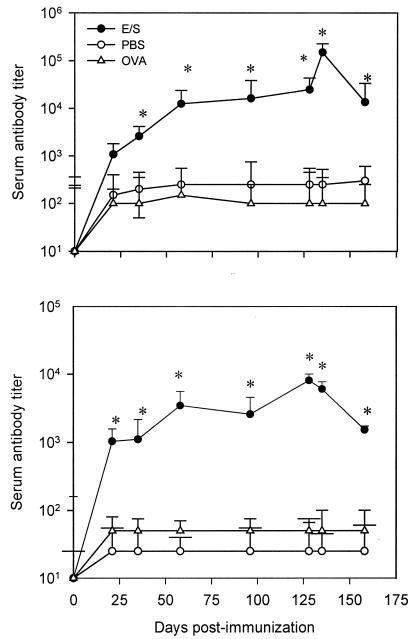

Oral administration of E/S Ags to BALB/c mice stimulated a specific humoral response as well as intestinal production of IgA antibodies in fecal samples. Circulating IgG1 antibody titers against E/S Ags showed a significant increase at day 58 until day 135 in E/S mice compared to control or OVA mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Moderate production of anti-E/S IgG2a antibody was also observed, with a significant increase after 21 days and a gradual increase until 128 days after oral administration of E/S Ags compared to control or OVA mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). No positive reaction against E/S Ags was observed with serum samples from control or OVA mice.

FIG. 2.

Kinetics of serum antibody response of BALB/c mice orally immunized against Giardia E/S Ags. Antibody was revealed by using anti-IgG1 (top) or anti-IgG2a isotype antibody (bottom) (ELISA). Mice were orally administered Giardia E/S Ags (E/S), PBS, or OVA (see Materials and Methods). Each point represents the mean titer value ± SD obtained from individual serum samples from 10 mice. *, significant difference (P < 0.05).

Oral administration of G. intestinalis E/S Ags induced a systemic or mucosal specific IgA response.

Specific serum IgA antibody titers of E/S mice showed a mild increase at day 35, with a significant increase by day 58, compared to the control and OVA groups (P < 0.05) and subsequently remained stable until the end of the study (Fig. 3). On the other hand, levels of fecal anti-E/S Ag IgA antibody increased clearly after day 14, but not significantly, and pursued a gradual increase until day 96. Significant levels of fecal IgA antibodies compared to those observed in control or OVA mice were detected at days 128 and 135 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Kinetics of IgA antibody response in serum or fecal samples of BALB/c mice orally immunized against Giardia E/S Ags. Individual levels of specific IgA antibody in serum (top) and fecal (bottom) samples were determined. Mice were orally administered Giardia E/S Ags (E/S), PBS, or OVA (see Materials and Methods). Each point represents the mean titer value ± SD obtained from individual serum or fecal samples from 10 mice. OD values were measured at 450 nm. *, significant difference (P < 0.05).

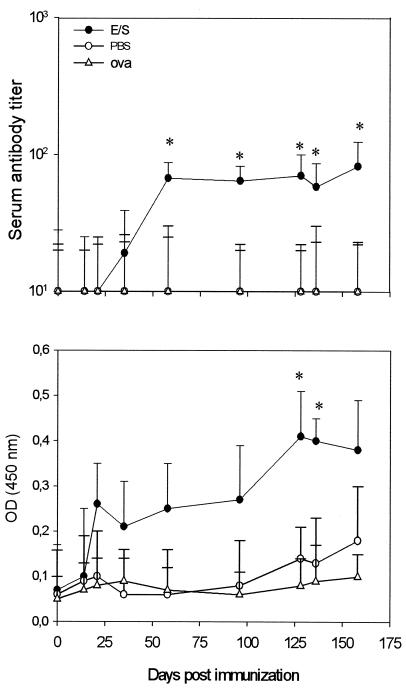

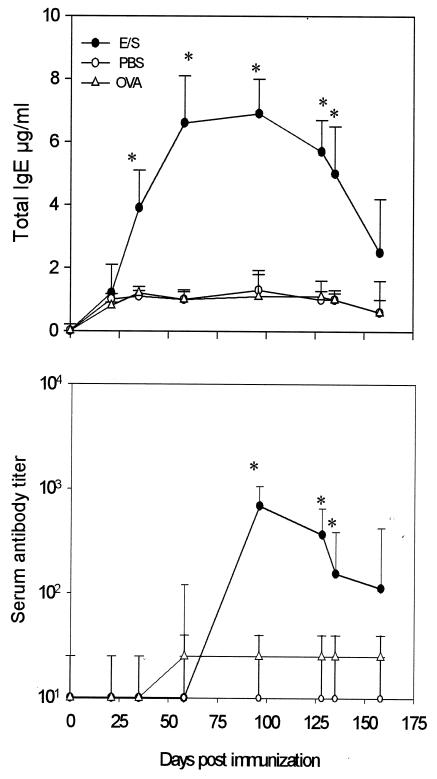

E/S Ags from G. intestinalis induced both specific and total IgE responses.

Oral administration of E/S Ags induced a significant increase of total IgE serum levels in E/S mice from day 35 to day 96 after oral immunization (P < 0.05). A decline in the concentration of total IgE was recorded after day 135 (Fig. 4). Specific IgE antibody levels were increased after day 58, with a peak at day 96 (P < 0.05) followed by a gradual decrease at the end of the kinetic follow-up (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Kinetics of total and specific IgE antibody responses in serum samples of BALB/c mice orally immunized against Giardia E/S Ags. Mice were orally administered Giardia E/S Ags (E/S), PBS, and OVA (see Materials and Methods). Each point represents the total IgE concentration (in micrograms per milliliter) ± SD (top) or specific IgE (bottom) mean titer value ± SD obtained from individual serum samples from 10 mice. *, significant difference (P < 0.05).

Identification of G. intestinalis E/S Ags by the sera of E/S-immunized mice.

To further support our observation that a specific humoral response occurred after oral administration of E/S Ags, we attempted to identify the proteins recognized by the specific serum antibodies (Fig. 5). Sera of E/S mice recognized eight protein bands. When anti-mouse IgG1 isotype antibody was used to identify the reacting serum antibody, eight 15- to 72-kDa bands were revealed. The anti-mouse IgA isotype antibody revealed three E/S antigenic bands of 50, 58, and 63 kDa, whereas the anti-mouse IgE isotype antibody revealed at least three bands of 15, 58, and 63 kDa, respectively (Fig. 5). No reactivity for IgG2a antibody was detected. It has to be noted that proteolytic activity was revealed by zymogram analysis in the zone of bands of 15, 17, 58, 63, and 72 kDa (Fig. 5).

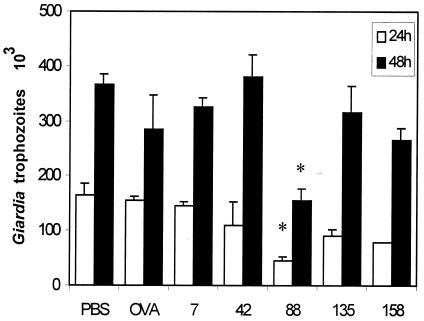

Activity of anti-E/S Ag serum antibody on G. intestinalis trophozoite growth.

To evaluate the functional activity of the serum of E/S mice against Giardia trophozoites, parasites were incubated in the presence of pooled E/S mouse heat-inactivated serum samples obtained at 7, 42, 88, 135, and 158 days after oral administration of E/S Ags. Incubation of Giardia trophozoites with pooled heat-inactivated mouse serum obtained on day 88 after immunization resulted in a significant growth inhibition of the parasites (P < 0.05). Parasite microcultures incubated with PBS or sera from OVA mice were used as controls of trophozoite growth (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Effect of sera from BALB/c mice immunized with Giardia E/S Ag on parasite viability. Trophozoites from the P1 strain (6 × 104 parasites/ml) were preincubated with heat-inactivated pooled serum samples obtained at 7, 42, 88, 135, and 158 days after immunization and diluted 1:20. Parasites were then subcultivated in fresh medium under optimal growth conditions for 24 h (open bars) or 48 h (filled bars). The data represent growth rates of Giardia trophozoites preincubated in serum from E/S-immunized mice, control mice (PBS), or OVA-immunized mice (OVA). Data represent mean values ± SD obtained from two triplicate individual experiments. *, significant difference (P < 0.05).

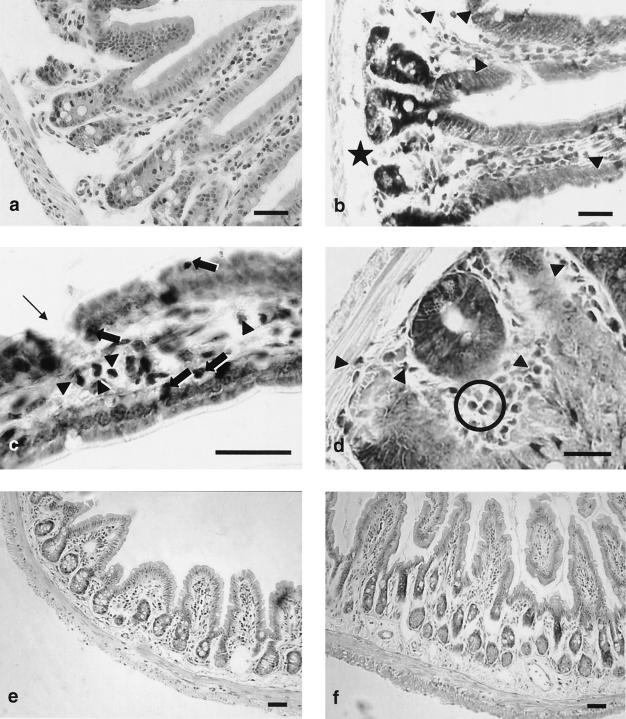

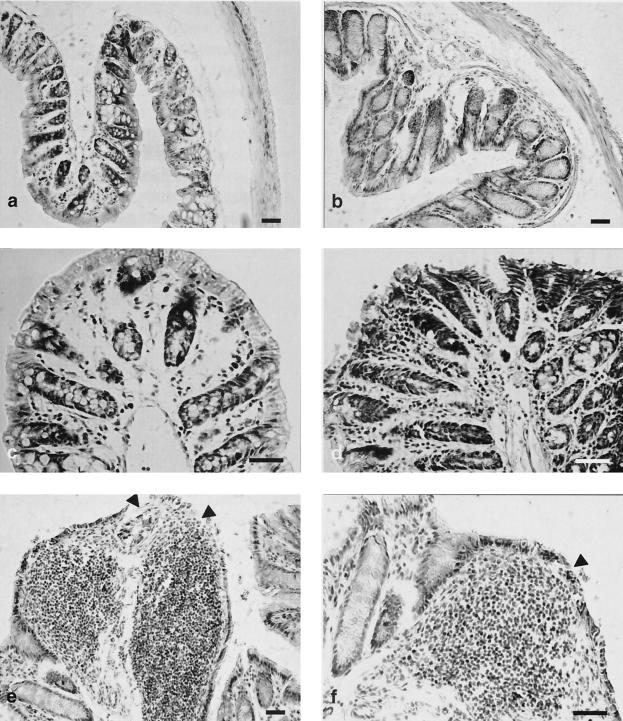

G. intestinalis E/S Ags induced histological changes in the intestines of BALB/c mice.

Histological analysis of intestinal samples (Fig. 7 and 8) from E/S mice sacrificed at day 158 has revealed moderate to important changes in the duodenum, ileum, and colon. In the duodenal sections (Fig. 7a to d), moderate changes included discontinuities of the enterocytic lining, intraepithelial leukocytes (Fig. 7c), mild chorion hypercellularity with moderate eosinophilic infiltrate (Fig. 7b to d), and edema in the submucous (Fig. 7b) and subserous layers. The ileum did not show important changes, except an apparent thickening of the submucous layer (Fig. 7e and f). Most marked changes were observed in the colon (Fig. 8), which showed enterocyte desquamation (Fig. 8e and f), invasion of the enterocyte lining by leukocytic cells, and mild hypertrophy of Lieberkühn crypts (Fig. 8b). A remarkable chorion hypercellularity (Fig. 8d), which sometimes evolved into extensive mononuclear cell infiltrates (Fig. 8e and f), which included macrophages, lymphocytes, fibroblasts, and mast cells, was also observed. These changes were usually associated with a mild submucous edema.

FIG. 7.

Histological changes in the small intestines of BALB/c mice induced by G. intestinalis E/S Ags. (a to d) Duodenum; (e to f) ileum; (a and e) control mice, hematoxylin-eosin stain; (b, c, d, and f) mice orally inoculated with E/S Ag; (b) May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain, arrowheads indicate eosinophilic cells and the star indicates submucous edema; (c) May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain, arrowheads indicate eosinophilic cells, thick arrows indicate intraepithelial leukocytes, and the thin arrow indicates enterocytic discontinuity; (d) May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain, a Lieberkühn gland is clearly visible in the center, arrowheads and circle indicate eosinophilic cells; (f) apparent thickening of the submucous layer. Bars, 20 μm.

FIG. 8.

Histological changes in the large intestines of BALB/c mice induced by G. intestinalis E/S Ags. (a and c) Control mice, hematoxylin-eosin stain; (b, d, e, and f) mice orally inoculated with E/S Ag; (b) mild hypertrophy of Lieberkühn glands, hematoxylin-eosin stain; (d) marked hypercellularity in the chorion layer associated with enterocytic desquamation, May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain; (e to f) noticeable, extensive, mononuclear cell infiltrates in the chorion associated with enterocytic desquamation (arrowheads), May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain. Bars, 20 μm.

G. intestinalis E/S Ags induced increased eosinophilic cell numbers in BALB/c mouse intestines.

The presence of eosinophils was evaluated in sections of the small and large intestines of mice 158 days after oral administration of E/S Ags. In the control group, eosinophils were predominantly located in the crypts, whereas in E/S mice, eosinophils were detected throughout the villi. Eosinophil counts in small and large intestine segments revealed that these cells were more numerous in E/S mice than in control mice. Mice in the E/S group had 5.3 ± 2.3 eosinophils/VCU in the small intestine, while control mice had 1.5 ± 1.0 eosinophils/VCU (P < 0.05). Likewise, in the large intestine, a value of 8.3 ± 3.7 eosinophils/VCU was found in the E/S mouse group versus 3.0 ± 1.4 eosinophils/VCU (P < 0.05) for the control group.

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the present results, it can be suggested that G. intestinalis E/S Ags administered orally to BALB/c mice in the absence of adjuvant can elicit an antibody response characterized by production of high levels of circulating anti-E/S Ag IgG1 antibody and moderate levels of specific IgG2a antibody. Moreover, production of total or specific IgE and specific serum or fecal IgA anti-E/S Ag antibodies was observed. Until now, the nature and the role of E/S Ags from G. intestinalis have not been widely investigated. The E/S products for G. intestinalis trophozoites were initially described as polydispersed Ags ranging between 94 and 225 kDa (35). In the present study, electrophoresis analysis of E/S products showed a complex pattern of 15- to 175-kDa proteins, whereas zymographic analyses confirmed our previous results, i.e., identification of 36- to 175-kDa E/S Ags as proteins partially characterized as cysteine proteases (19). Moreover, in the present study two additional proteolytic bands of 15 and 17 kDa were revealed.

Cysteine proteases have been identified as responsible for the major proteolytic activity in trophozoites of G. intestinalis (16, 37, 47, 49). A 30-kDa protease directly involved in the excystation of the parasite was identified; it was inhibited by E-64, a specific inhibitor of cysteine proteases. In addition, it was demonstrated that cysteine proteases play an important role in parasite differentiation (49). The results of the present work suggest that E/S products are responsible, at least partially, for the local and humoral response observed. It was previously reported that specific IgG1 antibody was induced in mice by oral administration of a Giardia 72-kDa recombinant variable surface protein (43). In the present work, E/S Ags elicited high titers of specific IgG1, IgA, and IgE antibodies, a profile that is consistent with a Th2 response, and recognized proteins of 15, 63, and 72 kDa, which seemed to support proteolytic activity.

On the other hand, Giardia serum IgA antibody plays an important role in parasite clearance as well as control of Giardia infection (25). Moreover, studies in natural and experimental hosts suggested that local secretory IgA-specific antibody are involved in the elimination of parasites from the intestine (44, 45). Under our work conditions, the oral administration of E/S Ags induced a specific IgA serum antibody response that was detected from day 58 after immunization to the end of the study. Moreover, significant fecal IgA-specific antibody was also detected. These results indicate that E/S Ags were able to stimulate the systemic and local specific IgA antibody responses. The induction of both systemic and local specific IgA responses might be the result of interleukin 6 (IL-6) production in response to continuous exposure to E/S Ags, a cytokine that has been implicated in the switching of IgA production (14, 30).

Intestinal parasite helminthic infections in the mouse model show a clear-cut association between the presence of molecules with cysteine protease activity and the increase of IgE production, which is involved in the polarization of the immune response to a Th2 type profile (23, 42). Consistently, in the present study, total and specific IgE antibody against E/S Ag was detected. This result suggested that E/S Ags could contain allergen-like molecules able to enhance the total and specific IgE production. For example, the E/S Ags of 15, 63, and 72 kDa could be potential candidates responsible for these effects. However, the link between the allergenicity of Giardia Ags and the proteolytic activity of some E/S proteins of G. intestinalis remains to be determined.

The oral administration of E/S Ags or cytosolic or membrane fractions of G. intestinalis to C57BL/6 mice was unable to induce either specific IgE or mucosal IgA antibodies (11). This unresponsiveness to parasite Ags could be related to the mouse strain. Actually, BALB/c mice exhibit an innate Th2 response to parasite infections or exogenous Ags, whereas C57BL/6 mice promote a dominant innate Th1 response to the same stimuli. This divergence could be explained by the genetic modulation of IL-4 production in BALB/c mice (33, 40).

The incubation of strain P1 Giardia trophozoites with heat-inactivated serum of mice inoculated with E/S Ags deeply impaired the in vitro parasite growth, suggesting that anti-E/S Ag antibody exerted a cytotoxic effect. Similar results have been described for monoclonal antibodies produced against Giardia surface Ags (4, 17, 36). These antibodies were able to induce the immobilization and aggregation of parasites, leading to their subsequent entrapment in the intestinal mucus (45). These results emphasize the interest of a better understanding of mechanisms underlying the control of the parasite infection, the nature of the Ags involved in such a response, and the identification of antibody isotypes involved in the cytotoxic effect.

Although G. intestinalis infection is not invasive, it is capable of causing brush border alteration, diarrhea, and malabsorption (6, 7). The oral administration of E/S Ags induced intestinal alterations similar to those reported during Giardia infection in the mouse model (41, 52). This result suggests that one or several components of E/S Ags may interact with the absorptive cells promoting alterations of enterocyte function (52). Recently, Teoh et al. (46) demonstrated that living parasites, parasitic extracts, and E/S Ags were able to induce alterations of cytoskeleton proteins (such as F-actin and α-actin) as well as the reduction of electrical resistance (46). More recently, it was demonstrated that contact with parasites induced apoptosis in nontransformed human duodenal epithelial cells, and this effect was abolished in the presence of a caspase-3 inhibitor (9). The assumption that cysteine proteases present in E/S Ags of G. intestinalis impair the enterocyte function is based on results in which cysteine proteases present in Entamoeba histolytica acts as an IL-1β-converting enzyme (ICE). ICE was able to activate the transcription of NF-κB in the human intestinal epithelial cell, a molecule involved in the inflammatory response (53). The potential implication of proteases or other proteins of Giardia E/S Ags with similar mechanisms should be explored. Gastrointestinal tract diseases like eosinophilic gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, helminthic or protozoan infections, and allergic disorders are usually associated with eosinophil infiltration (2). However, the links between Giardia infection and this phenomenon have not been elucidated. In the present study, an increase of eosinophil numbers in villi of E/S mice was observed, suggesting that E/S Ags can induce the migration and local accumulation of these cells. These processes can be regulated by the local production of chemoattractants such as eotaxin (29). Actually, this chemokine represents the primary regulator of the intestinal homing of eosinophils and also displays a basic role in innate immunity (32). E/S Ags could promote the local production of eotaxin by the enterocytes, a process that could explain the eosinophil accumulation recorded in the guts of mice that received E/S Ags. On the whole, our findings open new ways for understanding the immune response to Giardia infection as well as the potential involvement of Giardia E/S Ags in the mucosal injuries associated with giardiasis.

Acknowledgments

J.C.J. was supported by fellowships from “Fondo Nacional para el Desarrollo de las Ciencias y Tecnologías” (FONACIT) and “Consejo de Desarrollo Humanístico y Científico” (Universidad Central de Venezuela). This work was developed in part in the framework of the Ecology of Pathogenic Eukaryotic Microorganisms Project (EA-3609-IFR-17) supported by the French Ministry of Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam, R. D. 2001. Biology of Giardia lamblia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:447-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artis, D., N. E. Humphreys, C. S. Potten, N. Wagner, W. Muller, J. R. McDermott, R. K. Grencis, and K. J. Else. 2000. Beta7 integrin-deficient mice: delayed leukocyte recruitment and attenuated protective immunity in the small intestine during enteric helminth infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 3:1656-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belosevic, M., G. M. Faubert, and J. D. MacLean. 1989. Disaccharidase activity in the small intestine of gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) during primary and challenge infections with Giardia lamblia. Gut 30:1213-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belosevic, M., G. M. Faubert, and D. Dharampaul. 1994. Antimicrobial action of antibodies against Giardia muris trophozoites. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 95:485-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buret, A., D. G. Gall, P. N. Nation, and M. E. Olson. 1990. Intestinal protozoa and epithelial cell kinetics, structure and function. Parasitol. Today 6:375-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buret, A., J. A. Hardin, M. E. Olson, and D. G. Gall. 1992. Pathophysiology of small intestinal malabsorption in gerbils infected with Giardia lamblia. Gastroenterology 103:506-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buret, A. D., D. G. Gall, and M. E. Olson. 1992. Growth activities of enzymes in the small intestine, and ultrastructure of microvillous border in gerbils infected with G. duodenalis. Parasitol. Res. 77:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, N., J. A. Upcroft, and P. Upcroft. 1995. A Giardia duodenalis gene encoding a protein with multiple repeats of a toxin homologue. Parasitology 111:423-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin, A. C., D. A. Teoh, K. G.-E. Scott, J. B. Meddings, W. K. Macnaughton, and A. G. Buret. 2002. Strain-dependent induction of enterocyte apoptosis by Giardia lamblia disrupts epithelial barrier function in a caspase-3-dependent manner. Infect. Immun. 70:3673-3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Prisco, M. C., I. Hagel, N. R. Lynch, J. C. Jimenez, R. Rojas, M. Gil, and E. Mata. 1998. Association between giardiasis and allergy. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 81:261-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn, L. A., J. A. Upcroft, E. V. Fowler, B. S. Matthews, and P. Upcroft. 2001. Orally administered Giardia duodenalis extracts enhance an antigen-specific antibody response. Infect. Immun. 69:6503-6510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckman, L., and F. D. Gillin. 2001. Microbes and microbial toxins: paradigms for microbial-mucosal interactions. I. Pathophysiological aspects of enteric infections with the lumen-dwelling protozoan pathogen Giardia lamblia. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 280:G1-G6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farthing, M. J. G. 1993. Diarrhoeal disease: current concepts and future challenges (pathogenesis of giardiasis). Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 87:S17-S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodrich, M. E., and D. W. McGee. 1999. Effect of intestinal cell cytokines on mucosal B-cell IgA secretion: enhancing effect of epithelial-derived IL-6 but not TGF-beta on IgA+ B cells. Immunol. Lett. 67:11-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guy, R. A., S. Bertrand, and G. M. Faubert. 1991. Modification of RPMI 1640 for use in vitro immunological studies of host-parasite interaction in giardiasis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:627-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hare, D. F., E. L. Jarroll, and D. G. Lindmark. 1989. Giardia lamblia: characterization of proteinase activity in trophozoites. Exp. Parasitol. 68:168-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemphill, A., S. Stäger, B. Gottstein, and N. Müller. 1996. Electron microscopical investigation of surface alterations on Giardia lamblia trophozoites after exposure to a cytotoxic monoclonal antibody. Parasitol. Res. 82:206-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gogly, B., N. Groult, W. Hornebeck, G. Godeau, and B. Pellat. 1998. Collagen zymography as a sensitive and specific technique for the determination of subpicogram levels of interstitial collagenase. Anal. Biochem. 255:211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiménez, J. C., G. Uzcanga, A. Zambrano, M. C. Di Prisco, and N. R. Lynch. 2000. Identification and partial characterization of excretory/secretory products with proteolytic activity in Giardia intestinalis. J. Parasitol. 86:859-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaur, H., H. Samra, S. Ghosh, V. K. Vinayak, and N. K. Ganguly. 1999. Immune effector responses to an excretory-secretory product of Giardia lamblia. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 23:93-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaur, H., S. Ghos, H. Samra, V. K. Vinayak, and N. K. Ganguly. 2001. Identification and characterization of an excretory/secretory procut from Giardia lamblia. Parasitology 123:347-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keister, D. B. 1983. Axenic culture of Giardia lamblia in TYI-S-33 medium supplemented with bile. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77:487-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong, Y., S.-Y. Kang, S. H. Kim, and S.-Y. Cho. 1996. A neutral cysteine protease of Spirometra mansoni plerocercoid invoking an IgE response. Parasitology 114:263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 277:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langford, T. D., M. P. Housley, M. Boes, J. Chen, M. F. Kagnoff, F. D. Gillin, and L. Eckmann. 2002. Central importance of immunoglobulin A in host defense against Giardia spp. Infect. Immun. 70:11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lengerich, E. J., D. G. Addiss, and D. D. Juranek. 1994. Severe giardiasis in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 18:760-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lockwood, B. C., M. J. North, K. I. Scott, A. F. Bremmer, and G. H. Coomb. 1987. The use of a highly sensitive electrophoretic method to compare the proteinase of Trichomonas. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 24:89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lujan, H. D., M. R. Mowatt, and T. E. Nash. 1997. Mechanisms of Giardia lamblia differentiation into cysts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:294-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luster, A. D., and M. E. Rothenberg. 1997. Role of the monocyte chemoattractant protein and eotaxin subfamily of chemokines in allergic inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 62:620-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazanec, M. B., J. G. Nedrud, C. S. Kaetzel, and M. E. Lamm. 1993. A three-tiered view of the role of IgA in mucosal defense. Immunol. Today 14:430-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer, E. A., and S. Radulescu. 1979. Giardia and giardiasis. Adv. Parasitol. 7:1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mishra, A., S. P. Hogan, J. J. Lee, P. S. Foster, and M. E. Rothenberg. 1999. Fundamental signals that regulate eosinophil homing to the gastrointestinal tract. J. Clin. Investig. 103:1719-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosmann, T. R., and R. L. Coffman. 1989. Th1 and Th2 cells: different patterns of cytokine secretion lead to different function properties. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 7:145-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller, N., and B. Gottstein. 1998. Antigenic variation and the murine immune response to Giardia lamblia. Int. J. Parasitol. 28:1829-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nash, T. E., F. D. Gillin, and P. D. Smith. 1983. Excretory-secretory products of Giardia lamblia. J. Immunol. 131:2004-2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nash, T. E., and A. Aggarwal. 1986. Cytotoxicity of monoclonal antibodies to a subset of Giardia isolates. J. Immunol. 136:2628-2632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.North, M. J., J. C. Mottram, and G. H. Coombs. 1990. Cysteine proteinases of parasitic protozoa. Parasitol. Today 6:270-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pérez, O., M. Lastre, F. Bandera, M. Diaz, I. Domenech, R. Fagundo, D. Torres, C. Finlay, C. Campa, and G. Sierra. 1994. Evaluation of the immune response in symptomatic and asymptomatic human giardiasis. Arch. Med. Res. 25:171-177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poulin-Godefroy, O., S. Gaubert, S. Lafitte, A. Capron, and J. M. Grzych. 1996. Immunoglobulin A response in murine schistosomiasis: stimulatory role of egg antigens. Infect. Immun. 64:763-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reiner, S. L., and R. A. Seder. 1995. T helper cell differentiation in immune response. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 7:360-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott, K. G., J. B. Meddings, D. R. Kirk, S. P. Lees-Miller, and A. G. Buret. 2002. Intestinal infection with Giardia sp. reduces epithelial barrier function in a myosin light chain kinase-dependent fashion. Gastroenterology 123:1179-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shinjiro, I., T. Horoyuki, F. Yuko, M. Riho, and F. Koichiro. 2001. A factor inducing IgE from a filarial parasite is an agonist of human CD40. J. Biochem. Chem. 276:46118-46124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stäger, S., B. Gottstein, and N. Müller. 1997. Systemic and local antibody response in mice induced by a recombinant peptide fragment from Giardia lamblia variant surface protein (VSP) H7 produced by a Salmonella typhimurium vaccine strain. Int. J. Parasitol. 27:965-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stäger, S., R. Felleisen, B. Gottstein, and N. Müller. 1997. Giardia lamblia variant surface protein H7 stimulates a heterogeneous repertoire of antibodies displaying differential cytological effects on the parasite. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 85:113-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stäger, S., B. Gottstein, H. Sager, T. W. Jungi, and N. Müller. 1998. Influence of antibodies in mother's milk on antigenic variation of Giardia lamblia in the murine mother-offspring model of infection. Infect. Immun. 66:1287-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teoh, D. A., D. Kamieniecki, G. Pang, and A. G. Buret. 2000. Giardia lamblia rearranges F-actin and alpha-actin in human colonic and duodenal monolayers and reduces transepithelial electrical resistance. J. Parasitol. 86:800-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Touz, M. C., M. J. Nores, I. Slavin, C. Carmona, J. T. Conrad, M. R. Mowatt, T. E. Nash, C. E. Coronel, and H. D. Luján. 2002. The activity of a developmentally regulated cysteine proteinase is required for cyst wall formation in the primitive eukaryote. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8474-8481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of protein from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ward, W., L. Alvarado, N. D. Rawlings, J. C. Engel, C. Franklin, and J. H. McKerrow. 1997. A primitive enzyme for a primitive cell: the protease required for excystation of Giardia. Cell 89:437-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Werries, E., A. Franz, H. Hippe, and Y. Acil. 1991. Purification and substrate specificity of two cysteine proteinases of Giardia lamblia. J. Protozool. 38:378-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams, A. G., and G. H. Coombs. 1995. Multiple protease activities in Giardia intestinalis trophozoites. Int. J. Parasitol. 25:771-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williamson, A. L., P. J. O'Donoghue, J. A. Upcroft, and P. Upcroft. 2000. Immune and pathophysiological responses to different strains of Giardia duodenalis in neonatal mice. Int. J. Parasitol. 30:129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang, Z., L. Wang, K. B. Seydel, E. Li, S. Ankri, D. Mirelman, and S. L. Stanley, Jr. 2000. Entamoeba histolytica cysteine proteinases with interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme (ICE) activity cause intestinal inflammation and tissue damage in amoebiasis. Mol. Microbiol. 37:542-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]