Abstract

Profiles of antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus in 445 probable SARS patients and 3,749 healthy people or non-SARS patients were analyzed by antigen-capturing enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Antinucleocapsid antibodies were elucidated in 17.5% of the probable SARS patients 1 to 7 days after the onset of symptoms and in 80% of the patients 8 to 14 days after the onset. About 90% of the probable SARS patients were positive 15 or more days after illness. Antibody titers increased up to 70 days, and high antibody titers were maintained at least for another 3 months. Of the healthy people and non-SARS patients, only seven (0.187%) were weakly positive.

The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus (CoV) has been identified as the etiologic agent of SARS (1, 3, 5). It has been demonstrated that, at least in early responses, the antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein (N protein) predominate, as assayed by Western blotting and proteomic analysis. To understand the humoral immunity to the N protein of SARS CoV and the possibility of using the N protein in SARS diagnosis, antibodies to the N protein from 445 patients who probably had SARS, as diagnosed on the basis of World Health Organization criteria, from four hospitals were analyzed by an antigen-capturing enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in which recombinant SARS N protein was used as the antigen (6). The method is briefly described as follows. The N-encoding gene of SARS CoV was cloned into T7 promoter-based prokaryotic expression vector pET22b (Novagen), and the resulting recombinant plasmid (pMG-N) was then transformed into Escherichia coli BL21a(DE3). The recombinant N protein was expressed in E. coli by induction with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at 0.5 mmol/liter and purified by S-Sepharose Fast Flow ion-exchange chromatography, followed by gel filtration with Superdex 200 (Amersham Pharmacia) to a purity of >97% as determined by laser densitometry of a silver-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel. The purified N protein was diluted to 1 μg/ml with 50 mM carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) and used to coat the wells of 96-well microplates at 4°C overnight, followed by blocking with 5% fetal bovine serum for 4 h at room temperature. In addition, N protein was conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma). An antigen-capturing enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was established for the detection of anti-N protein antibody present in sera. A 100-μl volume of serum was added to the well coated with recombinant N protein, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and then washed five times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20. A 10-μl volume of labeled antigen was added, and the plate was incubated for another 30 min and washed as already described, and then 100 μl of TMB substrate solution (0.1 mg of tetramethylbenzidine hydrochloride/ml, 0.01% H2O2 in 0.1 M acetate buffer, pH 5.8) was added, the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 20 min, the reaction was terminated by adding 50 μl of 2 N sulfuric acid, and the absorbance at 450 nm (A450) was determined. Samples with an A450 of >0.15 (average A450 + 5 standard deviations of 900 samples from healthy people) were considered to be positive.

As shown in Table 1, 17.2% of the patients who probably had SARS developed anti-N protein antibodies in 7 days after the onset of symptoms. Eighty percent of the patients were positive 8 to 14 days after falling ill, and about 90% were positive 15 to 42 after falling ill. Furthermore, 95.2% of the patients who had fallen ill 43 or more days previously were positive. A higher positivity rate was observed in this group. This could be explained by the fact that most of the patients could be traced back to several index cases in February and March 2003, so less overdiagnosis (diagnosis of non-SARS patients as probably having SARS) was found then (2). The results also indicated that the assay was of value in SARS diagnosis 7 to 10 days after symptom onset.

TABLE 1.

Development of virus-specific antibodies in probable SARS patients, other non-SARS patients, and healthy people

| Group | No. of days after onset of symptoms | No. of samples | No. of positive samples | Positive rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probable SARS patients | 1-7 | 58 | 10 | 17.2 |

| 8-14 | 60 | 48 | 80 | |

| 15-21 | 39 | 35 | 89.7 | |

| 22-42 | 121 | 107 | 88.4 | |

| 42 | 167 | 159 | 95.2 | |

| Non-SARS adult patients | 1,004 | 2 | 0.199 | |

| Non-SARS pediatric patients | 936 | 2 | 0.213 | |

| Health-care workers | 109 | 0 | 0 | |

| Healthy people | 1,700 | 3 | 0.176 |

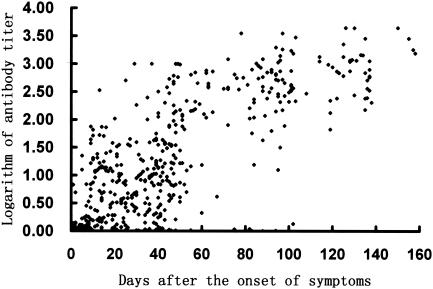

Anti-N protein antibody titers of 445 patients who probably had SARS were determined by serial dilution. The titer was calculated by the following formula: antibody titer = A450 × fold dilution/0.15. As shown in Fig. 1, low antibody titers (<1:100) were developed in 3 weeks after the onset of symptoms, antibody titers increased up to 1:1,000 in the next 5 weeks, and high antibody titers were maintained for at least another 3 months. No decrease in antibody titers was observed 158 days after the onset of symptoms. Serial samples from 21 SARS patients were also assayed, and a profile similar to that reported by Li et al.(4) was observed.

FIG. 1.

Development of anti-N protein antibody titers over time in 445 patients who probably had SARS.

To evaluate the specificity of the assay, antibodies to the N protein of SARS CoV from 3,749 non-SARS patients, health care works, and healthy people were assayed. Only 7 out of the 3,749 samples were shown to be weakly reactive (A450, <0.4 [cutoff value, 0.15]). This may have been caused by cross-reaction with other antibodies or by contamination with trace amounts of E. coli proteins in the antigen used in the assay. The false-positivity rate (0.187%) was significantly lower than that observed with an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using virus lysates as the antigen (about 2%), so the assay is highly specific. The results indicate that the assay of antibodies to the N protein antibody of SARS CoV could be used in the diagnosis of SARS infection and in epidemiologic surveys.

Acknowledgments

X.L., Y.S., and P.L. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drosten, C., S. Günther, W. Preiser, et al. 2003. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1967-1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hon, K. L. E., A. M. Li, and F. W. T. Cheng. 2003. Personal view of SARS: confusing definition, confusing diagnosis. Lancet 361:1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ksiazek, T. G., D. Erdman, C. S. Goldsmith, et al. 2003. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1953-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li, G., X. Chen, and A. Xu. Profile of specific antibodies to the SARS-associated coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 349:508-509. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Poutanen, S. M., D. E. Low, B. Henry, et al. 2003. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1995-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi, Y. L., Y. P. Yi, P. Li, T. Kuang, L. Li, M. Dong, Q. Ma, and C. Cao. 2003. Diagnosis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) by detection of SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid antibodies through antigen-capturing enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5781-5782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]