Abstract

Several studies have evaluated the potential utility of blood-based whole-transcriptome signatures as a source of biomarkers for schizophrenia. This endeavor has been complicated by the fact that individuals with schizophrenia typically differ from appropriate comparison subjects on more than just the presence of the disorder; for example, individuals with schizophrenia typically receive antipsychotic medications, and have been dealing with the sequelae of this chronic illness for years. The inability to control such factors introduces a considerable degree of uncertainty in the results to date. To overcome this, we performed a blood-based gene-expression profiling study of schizophrenia patients (n=9) as well as their unmedicated, nonpsychotic, biological siblings (n=9) and unaffected comparison subjects (n=12). The unaffected biological siblings, who may harbor some of the genetic predisposition to schizophrenia, exhibited a host of gene-expression differences from unaffected comparison subjects, many of which were shared by their schizophrenic siblings, perhaps indicative of underlying risk factors for the disorder. Several genes that were dysregulated in both individuals with schizophrenia and their siblings related to nucleosome and histone structure and function, suggesting a potential epigenetic mechanism underlying the risk state for the disorder. Nonpsychotic siblings also displayed some differences from comparison subjects that were not found in their affected siblings, suggesting that the dysregulation of some genes in peripheral blood may be indicative of underlying protective factors. This study, while exploratory, illustrated the potential utility and increased informativeness of including unaffected first-degree relatives in research in pursuit of peripheral biomarkers for schizophrenia.

INTRODUCTION

The identification of genes that increase susceptibility to schizophrenia, and the biological and environmental mechanisms through which they act, remain among the most challenging issues in neuropsychiatric research. Progress in mapping the human genome increased the viability of candidate gene association studies which, while important, have focused largely on genes in biological signaling systems that are already widely implicated in schizophrenia, such as dopamine or glutamate transmission (Glatt and others 2007). A new era of genome-wide association studies has advanced the field further, in part by implicating genes that were not suspected of roles in the disorder previously, such as zinc-finger proteins and calcium channels, while also substantiating some prior candidate genes in the major histocompatibility region on chromosome 6p (O'Donovan and others 2008; Shi and others 2009; Stefansson and others 2009). Such studies may ultimately explain much of the heritable portion of the liability toward schizophrenia, which is estimated to range from 60–85% (Cardno and others 1999; Sullivan and others 2003); however, a considerable fraction of the variance in who actually becomes affected will remain unexplained until the effects of environmental factors and gene-environment interactions can be systematically integrated into genomic research.

Gene expression, as a general index of genomic functionality, may be useful in this regard as a final common pathway in which the effects of genetic and environmental risk factors converge. In an earlier study, we derived messenger RNA (mRNA) expression patterns in circulating peripheral blood samples from patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and non-mentally ill control subjects (Tsuang and others 2005), which allowed us to distinguish a panel of relatively sensitive and specific biomarkers. Subsequently, we compared our blood-based biomarker set against a list of genes found to be dysregulated in schizophrenia in postmortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a brain structure often implicated in the disorder, finding six putative risk genes that might also have biomarker potential (Glatt and others 2005b).

These findings are encouraging, but they raise another set of critical questions about the vulnerability to schizophrenia. Among these are the issues of the extent to which our initial findings reflected the true biological susceptibility toward then disorder versus the effects of treatment (e.g., antipsychotic medications) or other, less specific manifestations of mental illness (e.g., psychosis). One potentially effective way of disentangling these effects is to study non-psychotic, biological relatives of individuals with schizophrenia, together with their ill siblings, and with non-mentally ill community comparison subjects. This approach would allow us to determine, for example, whether “unaffected” relatives who are neither psychotic nor taking antipsychotic medication still differ from comparison subjects, or whether relatives and individuals with schizophrenia share dysregulated genes compared to comparison subjects. We utilized this strategy in the present pilot study with subjects who were recruited from the Harvard University/Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center site of the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia (COGS) (Calkins and others 2007).

METHODS

Ascertainment and Clinical Characterization of Subjects

The COGS is a seven-site project, funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, which was designed to assess potential schizophrenia endophenotypes (e.g., social, psychophysiological, neurochemical or neuropsychological abnormalities) and perform genetic analyses on affected individuals (SZs), their unaffected biological siblings (SIBs) and other first-degree relatives, and community comparison subjects (CCSs) (Calkins and others 2007). Subjects in our study however, were ascertained only from one of the seven sites that participated in the COGS: the Harvard University site at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center (MMHC) Public Psychiatry Division of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). The institutional review boards of the MMHC and BIDMC approved the study, and all subjects signed informed consent.

The COGS methods will be summarized briefly as they have been described previously (Calkins and others 2007). Consortium-wide quality assurance procedures were exercised throughout the study. Each site followed an identical protocol to recruit, diagnose, assess endophenotypes, and collect blood samples for DNA analysis; in addition to these procedures, we introduced our previously validated protocol for mRNA analysis in peripheral blood. Medically healthy adults were recruited through flyers, print, and electronic media, and through community presentations. Individuals with schizophrenia were also referred by mental health providers. Eligible families had one of two pedigree structures. The first required availability of both of the proband’s parents, at least one of whom was not psychotic, and at least one non-psychotic sibling. The second included availability of one parent and at least two non-psychotic siblings. All subjects were administered a modified version of the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (Nurnberger and others 1994), the Family Interview for Genetic Studies (NIMH Genetics Initiative 1992), other clinical measures (see Calkins et al., 2007), and a medical record review. Premorbid IQ was estimated using the Wide Range Achievement Test, Third Edition (WRAT-3) Reading subtest (Jastak and Wilkinson 1993). All probands met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia and were stable clinically (i.e., no psychiatric hospitalizations in the previous month).

Subjects who were eligible for this gene expression study were 18–65 years old and fluent in English. Other exclusion criteria included: 1) a history of electroconvulsive therapy in the past 6 months; 2) a positive drug or alcohol test result during study screening; 3) a diagnosis of a substance abuse disorder in the past 30 days or active substance dependence in the past six months; 4) an estimated premorbid IQ<70; 5) a history of head injury with loss of consciousness exceeding 15 minutes; 6) a seizure disorder; 7) any ocular, neurological, or systemic medical problem likely to cause neurocognitive or psychophysiological performance deficits; or 8) inability to provide informed consent. CCS subjects were also excluded if they had a history of any DSM-IV Cluster A personality disorder, psychosis, or a family history of psychosis among first- or second-degree relatives.

For the present study, we ascertained and completed assessments of 32 subjects, including 8 SZs, 12 unaffected SIBs, and 12 CCSs. Despite the fact that no subjects dropped out of the study, our final sample size was somewhat smaller (n=26) due to our own data-filtering which excluded six subjects. First, two siblings had no corresponding proband in the sample and so were eliminated. Second, to simplify the design of our analyses, we included only one unaffected SIB for each SZ; yet, in two of the included families, there were two eligible SIBs for each SZ. In one of these families, one of the “unaffected” SIBs was found to have been diagnosed previously with major depressive disorder while the other unaffected SIB in this family had no history of any mental illness; thus, we excluded the former SIB and included the latter SIB in our analyses. In the second family with multiple unaffected SIBs, we found no clinical basis to favor inclusion of one of the SIBs over the other, and thus we elected to include the SIB whose profile of gene expression quality metrics most closely resembled that of their SZ relative. Finally, in one additional family, the “unaffected” SIB of one SZ subject was found to have been diagnosed previously with bipolar disorder; thus, we removed this entire family (both the SIB and the related SZ) from our analyses, leaving seven sibling-pairs and 12 CCSs. All probands were treated with antipsychotic medication at the time of testing, primarily clozapine, olanzapine, or quietiapine, whereas none of the CCSs or SIBs currently or recently received antipsychotic or other psychotropic medications.

mRNA Sample Acquisition, Stabilization, Isolation, and Storage

Approximately 15ml of blood were collected from each participant after overnight fasting, using a Vacutainer™ tube (Becton Dickinson; Franklin Lakes, NJ; USA). The collected blood samples were immediately stored on ice until mRNA was extracted, which always occurred within six hours after the blood was drawn. Red blood cells were ruptured with hypotonic hemolysis buffer (1.6mM EDTA, 10mM KHCO3, 153mM NH4C1, pH 7.4), and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were collected by centrifugation. PBMC total RNA was extracted with Trizol® Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

mRNA Quantitation and Quality Assurance

Data from four subjects (including two SZs and two SIBs) did not meet mRNA quality-control standards and thus these samples were removed from further analysis. The removal of the two SZs due to poor mRNA quality caused two additional SIBs to be left with no corresponding SZ relative in the dataset, and as such these SIBs were also removed from consideration. This left a final sample for analysis of 12 CCSs, 7 SZs, and 7 SIBs.

Five micrograms of total RNA from each sample was used for hybridization on an Affymetrix GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 microarray following the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression intensities were imported into GeneSpring v7.3.1 software (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) for analysis. The quality of the hybridization of each transcript was assessed by using the cross-gene error model, and measurements with a base/proportional ratio lower than 9.6 in more than 50% of hybridizations were removed prior to subsequent analysis. Genes showing inconsistent annotation provided by Affymetrix (www.affymetrix.com/products/arrays/specific/hgu133plus.affx) and SOURCE (genome-www5.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/source/sourceBatchSearch) were also removed from subsequent analyses.

Microarray Data Import, Normalization, Transformation, Summarization, and Analyses

Partek Genomics Suite software, version 6.5 (Partek Incorporated; St. Louis, MO), was utilized for all analytic procedures performed on microarray scan data. First, interrogating probes on the microarray were imported. Next, corrections for background signal were applied using the robust multi-array average (RMA) method (Irizarry and others 2003), with further adjustments for the GC-content of probes. The set of GeneChips was standardized using quantile normalization, and expression levels of each probe underwent log-2 transformation to yield distributions of data that more closely approximated normality. As each transcript was typically measured by multiple probe sets, summarization of redundant probe sets was obtained by median polish. According to convention (Handran and others 2002), probe sets with a maximum signal:noise ratio of less than 3.0 were excluded from subsequent analyses.

Transformed, normalized, and summarized gene-expression intensity values from each subject were utilized in three orthogonal sets of comparisons of diagnostic groups, as follows: 1) SZ vs. CCS; 2) SIB vs. CCS; and 3) SZ vs. SIB. These comparisons were made using analyses of variance (ANOVAs), with diagnostic group and any distinguishing demographics as fixed factors; when comparing SZs and SIBs, family ID was also modeled as a fixed factor.

After all quality-control procedures were executed, 54,675 probes of full-length gene transcripts were included in the analyses. The type-I-error rate (α) in each initial two-group comparison was set at 0.05; however, due to the large number of statistical tests to be performed, the probability of committing type-I errors (i.e., finding false-positive results) in this study was greatly inflated. We addressed this threat in three ways. First, we utilized intersection-union tests (IUTs) on sets of nominally significant (p<0.05) results, an approach which has been shown to be relatively (if not overly) conservative for identifying shared effects across conditions (Deng and others 2008). Second, we reduced the data (and the corresponding number of tests) through secondary analyses of groups of genes: after performing the IUTs, the generated lists of significantly dysregulated genes were subjected to the DAVID algorithm (Dennis and others 2003) to determine if they were enriched for genes that disproportionately represented biological “terms”. Specifically, we evaluated if each list of genes was enriched for genes that aggregated in the same functional categories (defined by Clusters of Orthologous Groups [COG] (Tatusov and others 2000) ontologies, Protein Information Resource [PIR] (Wu and others 2003) keywords, and Universal Protein Resource [UniProt] (Apweiler and others 2004) features), represented similar ontologies (defined by the Gene Ontology Consortium [GOC] (Ashburner and others 2000)), participated in the same biological pathways (defined by BioCarta and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes [KEGG] (Kanehisa and Goto 2000)), or exhibited common protein domains (defined by the Integrative Protein Signature database [InterPro] (Hunter and others 2009), PIR, or the Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool [SMART] (Schultz and others 1998)). Third, we applied a Bonferroni correction to the p-values obtained in the enrichment analyses of these terms, only considering significant those tests that exceeded a threshold of α=0.05/the number of terms evaluated in a particular category.

RESULTS

Demographics

The three groups of subjects were comparable in age, with means (±standard deviations) of 43.0±11.4 years for CCS, 39.4±11.1 for SZs, and 40.0±13.3 for SIBs (p>0.500 for all comparisons). The groups were also uniform with regard to ancestry, as all subjects self-identified as Caucasian, except for two CCS who self-identified as African-American. Exclusion of the two African-American CCS did not substantially alter the results, so these subjects were retained in order to maximize inferential power with regard to diagnosis. There was a significant gender disparity between the groups, as both the CCS and SIB groups included both male and female subjects (CCS: 9 males and 3 females; SIB: 4 males and 3 females) while all seven SZs were male (χ2(2)=10.1, p=0.006). As such, we controlled for sex (but not age or ancestry, in order to preserve degrees of freedom) in all subsequent statistical models.

SZ vs. CCS

Nominally significant (p<0.05) differences in levels of expression between SZs and CCS were observed for 2155 probes, of which 1246 were up-regulated and 909 down-regulated in SZs compared to CCS. Of these 2155 probes, 1593 “known probes” were complementary to 1473 recognized protein-coding mRNAs, KIAA or FLJ cDNAs, or open reading frames (collectively referred to as “known transcripts”), while 562 “unknown probes” complemented no presently recognized functional genomic element. Several known transcripts (k=110) were tagged by two or more dysregulated probes, further substantiating the evidence of their deviation between groups. Furthermore, ADAM28, CRKRS, HNRNPC, SMARCA5, and SPON1 each had three probes significantly dysregulated in SZs, while RPRD1A had four dysregulated probes and GM2A had five. In comparison to CCS, 819 known probes were up-regulated in SZ and 774 were down-regulated.

SIB vs. CCS

Nominally significant (p<0.05) differences in levels of expression between SIBs and CCS were observed for 2176 probes, of which 1418 were up-regulated and 758 down-regulated in SIBs compared to CCSs. Of these 2176 probes, 1636 known probes were complementary to 1493 known transcripts, while the remaining 540 probes were complementary to no known transcript. Several known transcripts (k=121) were tagged by two or more dysregulated probes. Furthermore, AGPAT3, AKT2, AP1S3, BNC2, CALU, HELQ, HNRNPC, KIAA0494, KLF6, LARP4, MBP, PDE4DIP, PIP5K1A, PPARA, PTGDS, TSPAN2, and ZNF81 each had three probes significantly dysregulated in SIBs, while CCDC50 had four dysregulated probes and ASPH had five. In comparison to CCSs, 1079 known probes were up-regulated in SIBs and 557 were down-regulated.

SZ vs. SIB

Nominally significant (p<0.05) differences in levels of expression between SZs and SIBs were observed for 1992 probes, of which 955 were up-regulated and 1037 down-regulated in SZs compared to SIBs. Of these 1992 probes, 1580 known probes were complementary to 1450 known transcripts, while the remaining 412 probes were complementary to no known transcript. Several known transcripts (k=115) were tagged by two or more dysregulated probes. Furthermore, C11ORF31, CD58, CNPY2, DCLK1, EPOR, KIAA1324, LAMP2, MUM1, RAB18, RAPGEF2, and STAM2 each had three probes significantly dysregulated in SZs, and CCPG1 and RUFY3 each had four. In comparison to SIBs, 733 known probes were up-regulated in SZs and 847 were down-regulated.

Intersection-Union Tests (IUTs)

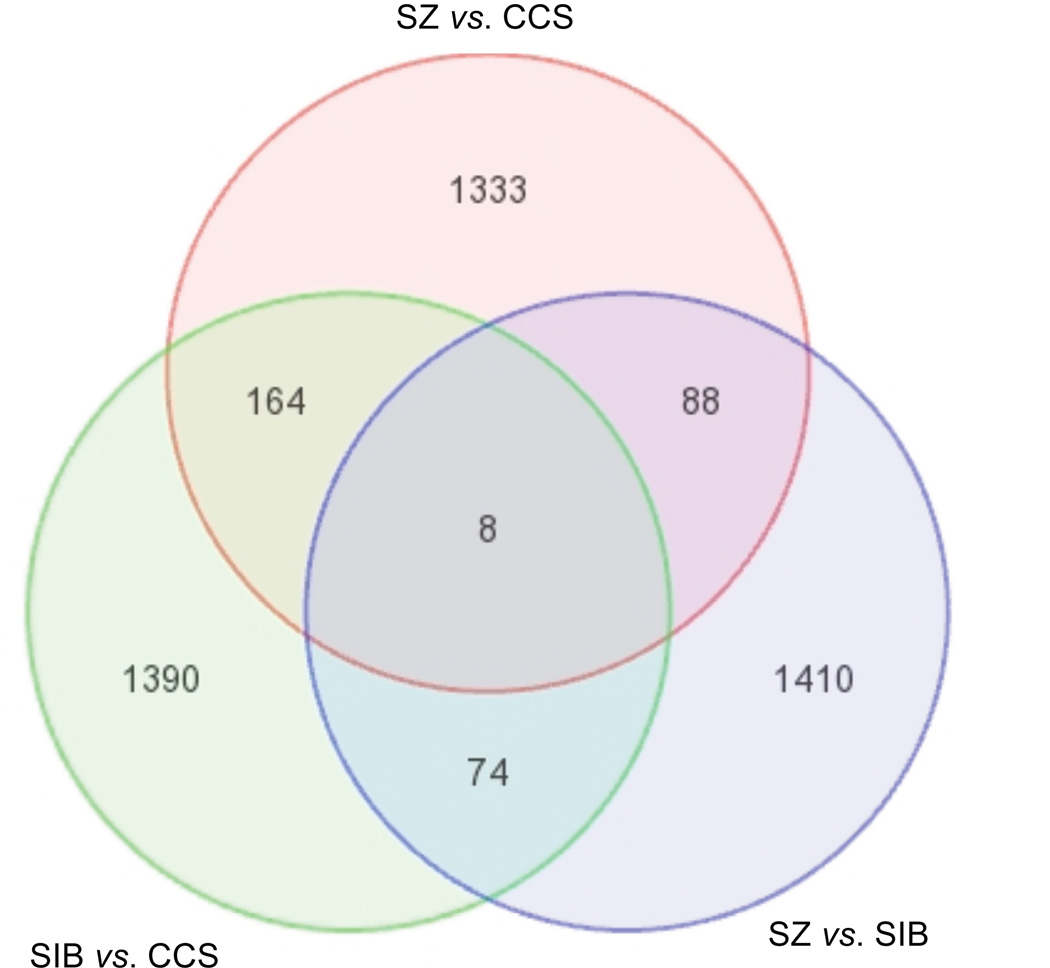

Figure 1 shows a Venn diagram depicting the numbers of probes for known transcripts that were dysregulated in each of the three orthogonal comparisons of diagnostic groups.

FIGURE 1.

Venn Diagram of Genes Dysregulated between Groups. SZ: schizophrenia group; SIB: first-degree biological sibling of SZ subject group; CCS: unrelated non-mentally ill community comparison subject group.

[SZ vs. CCS] ∩ [SIB vs. CCS]

Compared to CCSs, the SZ and SIB groups showed significant evidence (p<0.05 in both comparisons) of common dysregulation of 172 probes for 168 known transcripts (Table 1). Two of these genes (MBP and PIGV) were each tagged by two probes that were dysregulated in both SZs and SIBs compared to CCSs, and one gene (HNRNPC) was tagged by three commonly dysregulated probes. All probes except one (for SPIRE1) were dysregulated in the same direction (up- or down-regulated) in both SZs and SIBs compared to CCSs. Ninety-one probes were up-regulated in both groups, 80 were down-regulated in both groups, and SPIRE1 was up-regulated in SIBs and down-regulated in SZs compared to CCSs.

Table 1.

Genes Significantly Dysregulated in both the SZ and SIB Groups Compared to the CCS Group1

| Probeset ID |

Gene Symbol |

Gene Product |

SZ vs. CCS | SIB vs. CCS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | Fold-Change | p | Fold-Change | |||

| 235931_at | FAM119A | family with sequence similarity 119, member A | 2.49e−03 | 2.67 | 1.87e−02 | 1.75 |

| 212998_x_at | HLA-DQB1/LOC100294318 | major histocompatibility complex, class II, DQ beta 1 | 4.07e−02 | 1.88 | 3.01e−02 | 1.43 |

| 244546_at | CYCS | cytochrome c, somatic | 4.98e−02 | 1.61 | 8.83e−03 | 1.52 |

| 225155_at | SNHG5 | small nucleolar RNA host gene 5 (non-protein coding) | 3.82e−02 | 1.58 | 1.35e−02 | 1.46 |

| 235678_at | GM2A | GM2 ganglioside activator | 8.36e−04 | 1.68 | 9.62e−04 | 1.25 |

| 222347_at | LOC644450 | hypothetical protein LOC644450 | 1.97e−02 | 1.48 | 3.90e−02 | 1.29 |

| 203932_at | HLA-DMB | major histocompatibility complex, class II, DM beta | 2.98e−02 | 1.40 | 1.50e−02 | 1.26 |

| 217478_s_at | HLA-DMA/HLA-DMB | major histocompatibility complex, class II, DM alpha/beta | 2.20e−02 | 1.38 | 3.86e−02 | 1.18 |

| 219256_s_at | SH3TC1 | SH3 domain and tetratricopeptide repeats 1 | 3.84e−02 | 1.30 | 3.38e−02 | 1.20 |

| 205306_x_at | KMO | kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (kynurenine 3-hydroxylase) | 1.84e−02 | 1.28 | 4.55e−03 | 1.20 |

| 213244_at | SCAMP4 | secretory carrier membrane protein 4 | 4.60e−02 | 1.27 | 3.71e−02 | 1.19 |

| 241446_at | ADAM28 | ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 | 8.42e−03 | 1.26 | 1.22e−02 | 1.16 |

| 223349_s_at | BOK | BCL2-related ovarian killer | 4.33e−02 | 1.18 | 1.35e−03 | 1.23 |

| 244344_at | WNK4 | WNK lysine deficient protein kinase 4 | 5.32e−03 | 1.25 | 3.19e−02 | 1.15 |

| 1555872_a_at | LOC728903 | hypothetical LOC728903 | 4.96e−02 | 1.17 | 5.00e−04 | 1.22 |

| 219341_at | CLN8 | ceroid-lipofuscinosis, neuronal 8 (epilepsy, progressive with mental retardation) | 4.61e−02 | 1.21 | 1.11e−02 | 1.17 |

| 214693_x_at | NBPF10 | neuroblastoma breakpoint family, member 10 | 2.80e−02 | 1.23 | 3.66e−02 | 1.12 |

| 221362_at | HTR5A | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 5A | 4.48e−04 | 1.23 | 3.49e−02 | 1.11 |

| 213987_s_at | CDC2L5 | cell division cycle 2-like 5 (cholinesterase-related cell division controller) | 2.05e−02 | 1.20 | 3.66e−02 | 1.13 |

| 1555390_at | C14orf21 | chromosome 14 open reading frame 21 | 3.11e−02 | 1.16 | 5.04e−03 | 1.17 |

| 1558573_at | MCTS1 | malignant T cell amplified sequence 1 | 3.11e−02 | 1.19 | 1.04e−02 | 1.13 |

| 1557991_at | METTL6 | methyltransferase like 6 | 4.38e−02 | 1.18 | 1.47e−02 | 1.14 |

| 219518_s_at | ELL3/SERINC4 | elongation factor RNA polymerase II-like 3/serine incorporator 4 | 3.91e−02 | 1.16 | 4.83e−03 | 1.15 |

| 232042_at | TTYH2 | tweety homolog 2 (Drosophila) | 1.11e−02 | 1.22 | 3.23e−02 | 1.09 |

| 208136_s_at | MGC3771 | hypothetical LOC81854 | 3.46e−02 | 1.15 | 9.89e−04 | 1.16 |

| 238316_at | ZNF567 | zinc finger protein 567 | 5.83e−03 | 1.19 | 2.74e−02 | 1.11 |

| 1552671_a_at | SLC9A7 | solute carrier family 9 (sodium/hydrogen exchanger), member 7 | 2.24e−02 | 1.14 | 2.30e−02 | 1.16 |

| 227298_at | FLJ37798 | hypothetical gene supported by AK095117 | 1.64e−02 | 1.19 | 9.48e−03 | 1.11 |

| 221412_at | VN1R1 | vomeronasal 1 receptor 1 | 2.97e−02 | 1.14 | 1.41e−03 | 1.15 |

| 1554285_at | HAVCR2 | hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2 | 2.60e−02 | 1.16 | 4.31e−02 | 1.13 |

| 1563947_a_at | ERC1 | ELKS/RAB6-interacting/CAST family member 1 | 4.96e−02 | 1.16 | 2.08e−02 | 1.12 |

| 226918_at | JPH4 | junctophilin 4 | 2.63e−03 | 1.20 | 3.70e−02 | 1.08 |

| 216391_s_at | KLHL1 | kelch-like 1 (Drosophila) | 2.53e−02 | 1.14 | 8.23e−03 | 1.14 |

| 205009_at | TFF1 | trefoil factor 1 | 1.40e−02 | 1.15 | 1.89e−02 | 1.12 |

| 207049_at | SCN8A | sodium channel, voltage gated, type VIII, alpha subunit | 1.76e−02 | 1.15 | 7.92e−03 | 1.12 |

| 1569074_at | FLJ37078 | hypothetical protein FLJ37078 | 4.47e−03 | 1.15 | 8.79e−03 | 1.11 |

| 223926_at | KIF2B | kinesin family member 2B | 1.51e−02 | 1.16 | 3.49e−02 | 1.10 |

| 1562581_at | LOC254028 | hypothetical LOC254028 | 3.38e−02 | 1.17 | 4.56e−02 | 1.09 |

| 1570432_at | LOC100133287 | hypothetical protein LOC100133287 | 4.15e−02 | 1.14 | 1.64e−02 | 1.12 |

| 221132_at | CLDN18 | claudin 18 | 5.48e−03 | 1.16 | 1.32e−02 | 1.09 |

| 244500_s_at | EVI5L | ecotropic viral integration site 5-like | 1.71e−02 | 1.14 | 1.04e−02 | 1.11 |

| 220847_x_at | ZNF221 | zinc finger protein 221 | 3.41e−02 | 1.12 | 1.57e−03 | 1.13 |

| 1559277_at | FLJ35700 | hypothetical protein FLJ35700 | 2.41e−02 | 1.15 | 3.20e−02 | 1.10 |

| 1555108_at | SLC10A7 | solute carrier family 10 (sodium/bile acid cotransporter family), member 7 | 3.09e−04 | 1.15 | 1.55e−02 | 1.09 |

| 208115_x_at | C10orf137 | chromosome 10 open reading frame 137 | 1.78e−02 | 1.14 | 4.28e−02 | 1.10 |

| 208282_x_at | DAZ1/DAZ2/DAZ3/DAZ4 | deleted in azoospermia 1/2/3/4 | 3.61e−02 | 1.13 | 2.09e−02 | 1.11 |

| 215585_at | KIAA0174 | KIAA0174 | 2.14e−02 | 1.14 | 2.62e−02 | 1.10 |

| 1570128_at | DDX19A | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-As) box polypeptide 19A | 3.47e−02 | 1.13 | 1.71e−02 | 1.10 |

| 210261_at | KCNK2 | potassium channel, subfamily K, member 2 | 3.06e−02 | 1.15 | 3.44e−02 | 1.09 |

| 212924_s_at | LSM4 | LSM4 homolog, U6 small nuclear RNA associated (S. cerevisiae) | 4.34e−02 | 1.13 | 2.11e−02 | 1.10 |

| 227512_at | MEX3A | mex-3 homolog A (C. elegans) | 2.71e−02 | 1.13 | 2.63e−02 | 1.09 |

| 207024_at | CHRND | cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, delta | 3.77e−02 | 1.12 | 1.74e−02 | 1.11 |

| 220120_s_at | EPB41L4A | erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1 like 4A | 1.50e−03 | 1.16 | 2.60e−02 | 1.07 |

| 1561082_at | NID1 | nidogen 1 | 7.59e−03 | 1.14 | 4.66e−02 | 1.08 |

| 219839_x_at | TCL6 | T-cell leukemia/lymphoma 6 | 3.66e−03 | 1.12 | 1.62e−02 | 1.10 |

| 206510_at | SIX2 | SIX homeobox 2 | 1.77e−02 | 1.15 | 1.99e−02 | 1.07 |

| 214466_at | GJA5 | gap junction protein, alpha 5, 40kDa | 6.89e−03 | 1.14 | 9.31e−03 | 1.08 |

| 211624_s_at | DRD2 | dopamine receptor D2 | 2.12e−02 | 1.13 | 3.10e−02 | 1.09 |

| 1569570_at | AGBL4 | ATP/GTP binding protein-like 4 | 1.07e−02 | 1.12 | 2.00e−02 | 1.10 |

| 1554641_a_at | TET3 | tet oncogene family member 3 | 3.33e−02 | 1.12 | 2.97e−02 | 1.09 |

| 1564367_at | CXorf25 | chromosome X open reading frame 25 | 1.75e−02 | 1.14 | 8.67e−03 | 1.07 |

| 231338_at | C15orf55 | chromosome 15 open reading frame 55 | 4.72e−02 | 1.12 | 4.01e−02 | 1.09 |

| 236205_at | ABCC6P1 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C, member 6 pseudogene 1 | 3.23e−02 | 1.12 | 3.56e−02 | 1.09 |

| 1552885_a_at | NKX6-3 | NK6 homeobox 3 | 1.67e−02 | 1.13 | 3.04e−02 | 1.08 |

| 220191_at | GKN1 | gastrokine 1 | 4.84e−02 | 1.10 | 9.71e−03 | 1.10 |

| 216914_at | CDC25C | cell division cycle 25 homolog C (S. pombe) | 4.29e−02 | 1.12 | 3.38e−02 | 1.09 |

| 204746_s_at | PICK1 | protein interacting with PRKCA 1 | 4.48e−02 | 1.12 | 1.02e−02 | 1.09 |

| 1570366_x_at | ZNF564/ZNF709 | zinc finger protein 564/zinc finger protein 709 | 2.64e−02 | 1.10 | 1.93e−02 | 1.11 |

| 210195_s_at | PSG1 | pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein 1 | 2.87e−02 | 1.10 | 2.48e−02 | 1.10 |

| 1555131_a_at | PER3 | period homolog 3 (Drosophila) | 3.80e−02 | 1.10 | 2.60e−03 | 1.10 |

| 1558960_a_at | MFGE8 | Milk fat globule-EGF factor 8 protein | 2.65e−02 | 1.11 | 2.53e−02 | 1.09 |

| 227800_at | FAM110B | family with sequence similarity 110, member B | 2.25e−02 | 1.11 | 1.10e−02 | 1.09 |

| 1556095_at | UNC13C | unc-13 homolog C (C. elegans) | 4.99e−02 | 1.09 | 1.19e−03 | 1.10 |

| 213621_s_at | GUK1 | Guanylate kinase 1 | 4.78e−02 | 1.12 | 4.77e−02 | 1.07 |

| 40284_at | FOXA2 | forkhead box A2 | 8.49e−03 | 1.12 | 3.90e−02 | 1.07 |

| 216720_at | CYP2U1 | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily U, polypeptide 1 | 6.05e−03 | 1.10 | 2.46e−02 | 1.08 |

| 1565580_s_at | TATDN2 | TatD DNase domain containing 2 | 4.45e−02 | 1.12 | 2.75e−02 | 1.07 |

| 237939_at | EPHA5 | EPH receptor A5 | 9.87e−03 | 1.11 | 3.14e−02 | 1.08 |

| 1553930_at | TAAR1 | trace amine associated receptor 1 | 2.94e−03 | 1.12 | 4.61e−02 | 1.06 |

| 1562261_at | AMZ1 | archaelysin family metallopeptidase 1 | 2.77e−02 | 1.10 | 1.14e−02 | 1.08 |

| 207534_at | MAGEB1 | melanoma antigen family B, 1 | 6.74e−03 | 1.10 | 2.17e−02 | 1.07 |

| 211093_at | PDE6C | phosphodiesterase 6C, cGMP-specific, cone, alpha prime | 5.95e−03 | 1.10 | 3.33e−03 | 1.07 |

| 233767_at | HHLA1 | HERV-H LTR-associating 1 | 4.37e−02 | 1.09 | 1.88e−02 | 1.08 |

| 242973_at | CACNA1C | calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L type, alpha 1C subunit | 8.75e−03 | 1.09 | 5.48e−03 | 1.07 |

| 223673_at | RFX4 | regulatory factor X, 4 (influences HLA class II expression) | 3.58e−02 | 1.06 | 6.90e−03 | 1.10 |

| 1554329_x_at | STXBP4 | syntaxin binding protein 4 | 3.20e−02 | 1.08 | 2.62e−02 | 1.06 |

| 221470_s_at | IL1F7 | interleukin 1 family, member 7 (zeta) | 4.53e−02 | 1.08 | 1.79e−02 | 1.06 |

| 216492_at | KIR3DX1 | killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, three domains, X1 | 4.98e−02 | 1.08 | 3.28e−02 | 1.06 |

| 1560469_at | NR5A2 | nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 2 | 3.32e−02 | 1.07 | 4.07e−02 | 1.05 |

| 1562223_at | LOC642426 | hypothetical LOC642426 | 2.33e−02 | 1.05 | 1.17e−03 | 1.06 |

| 216966_at | ITGA2B | integrin, alpha 2b (platelet glycoprotein IIb of IIb/IIIa complex, antigen CD41) | 4.23e−02 | 1.06 | 1.76e−02 | 1.04 |

| 224995_at | SPIRE1 | spire homolog 1 (Drosophila) | 3.82e−02 | −1.19 | 4.18e−02 | 1.13 |

| 1553533_at | JPH1 | junctophilin 1 | 4.52e−02 | −1.06 | 2.57e−02 | −1.05 |

| 212043_at | TGOLN2 | trans-golgi network protein 2 | 3.65e−02 | −1.06 | 1.40e−02 | −1.06 |

| 242084_at | LOC339316 | hypothetical protein LOC339316 | 3.30e−02 | −1.07 | 3.80e−03 | −1.06 |

| 218192_at | IP6K2 | inositol hexakisphosphate kinase 2 | 3.08e−02 | −1.10 | 1.56e−02 | −1.06 |

| 213473_at | BRAP | BRCA1 associated protein | 4.31e−02 | −1.11 | 1.87e−02 | −1.07 |

| 226357_at | USP19 | ubiquitin specific peptidase 19 | 1.48e−02 | −1.11 | 4.44e−02 | −1.07 |

| 230374_at | LOC100294358 | hypothetical protein LOC100294358 | 3.30e−02 | −1.11 | 2.85e−02 | −1.07 |

| 204236_at | FLI1 | Friend leukemia virus integration 1 | 2.72e−02 | −1.10 | 4.04e−02 | −1.08 |

| 212626_x_at | HNRNPC | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (C1/C2) | 1.74e−03 | −1.12 | 6.46e−03 | −1.07 |

| 217673_x_at | GNAS | GNAS complex locus | 4.19e−02 | −1.12 | 1.75e−02 | −1.08 |

| 203351_s_at | ORC4L | origin recognition complex, subunit 4-like (yeast) | 2.25e−02 | −1.13 | 1.87e−02 | −1.07 |

| 1557639_at | NFIA | Nuclear factor I/A | 1.21e−02 | −1.13 | 4.33e−02 | −1.08 |

| 208398_s_at | TBPL1 | TBP-like 1 | 1.08e−02 | −1.14 | 4.52e−02 | −1.07 |

| 204665_at | SIKE1 | suppressor of IKBKE 1 | 3.71e−02 | −1.13 | 2.19e−02 | −1.09 |

| 223459_s_at | C1orf56 | chromosome 1 open reading frame 56 | 4.62e−02 | −1.12 | 1.28e−02 | −1.09 |

| 202293_at | STAG1 | stromal antigen 1 | 8.82e−03 | −1.16 | 2.65e−02 | −1.07 |

| 200014_s_at | HNRNPC | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (C1/C2) | 7.40e−03 | −1.16 | 4.32e−02 | −1.07 |

| 214737_x_at | HNRNPC | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (C1/C2) | 2.97e−03 | −1.15 | 1.10e−02 | −1.08 |

| 222212_s_at | LASS2 | LAG1 homolog, ceramide synthase 2 | 2.20e−02 | −1.11 | 6.80e−04 | −1.13 |

| 220663_at | IL1RAPL1 | interleukin 1 receptor accessory protein-like 1 | 2.71e−03 | −1.15 | 2.19e−02 | −1.10 |

| 222984_at | PAIP2 | poly(A) binding protein interacting protein 2 | 1.34e−02 | −1.16 | 1.53e−02 | −1.09 |

| 230123_at | NECAP2 | NECAP endocytosis associated 2 | 2.72e−02 | −1.16 | 1.56e−02 | −1.09 |

| 208741_at | SAP18 | Sin3A-associated protein, 18kDa | 1.33e−02 | −1.14 | 3.30e−02 | −1.11 |

| 219238_at | PIGV | phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis, class V | 1.55e−03 | −1.14 | 3.01e−04 | −1.12 |

| 205160_at | PEX11A | Peroxisomal biogenesis factor 11 alpha | 6.61e−03 | −1.16 | 1.51e−02 | −1.10 |

| 222867_s_at | MED31 | mediator complex subunit 31 | 3.37e−02 | −1.16 | 1.96e−02 | −1.10 |

| 51146_at | PIGV | phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis, class V | 3.21e−02 | −1.14 | 3.64e−02 | −1.12 |

| 226083_at | TMEM70 | transmembrane protein 70 | 4.24e−02 | −1.10 | 2.72e−03 | −1.16 |

| 223447_at | REG4 | regenerating islet-derived family, member 4 | 9.35e−03 | −1.16 | 3.83e−02 | −1.11 |

| 223416_at | SF3B14 | splicing factor 3B, 14 kDa subunit | 3.50e−02 | −1.12 | 9.53e−03 | −1.15 |

| 39549_at | NPAS2 | neuronal PAS domain protein 2 | 2.54e−02 | −1.16 | 1.81e−02 | −1.11 |

| 214052_x_at | BAT2D1 | BAT2 domain containing 1 | 4.31e−02 | −1.13 | 9.71e−03 | −1.15 |

| 200071_at | SMNDC1 | survival motor neuron domain containing 1 | 2.95e−03 | −1.19 | 2.92e−02 | −1.09 |

| 229594_at | SPTY2D1 | SPT2, Suppressor of Ty, domain containing 1 (S. cerevisiae) | 6.29e−04 | −1.18 | 4.33e−02 | −1.10 |

| 221118_at | PKD2L2 | polycystic kidney disease 2-like 2 | 1.35e−03 | −1.20 | 6.74e−03 | −1.10 |

| 208731_at | RAB2A | RAB2A, member RAS oncogene family | 1.96e−02 | −1.20 | 4.51e−02 | −1.11 |

| 227244_s_at | SSU72 | SSU72 RNA polymerase II CTD phosphatase homolog (S. cerevisiae) | 1.14e−02 | −1.19 | 1.14e−02 | −1.12 |

| 237052_x_at | GIGYF2 | GRB10 interacting GYF protein 2 | 4.70e−03 | −1.18 | 5.46e−03 | −1.13 |

| 222414_at | MLL3 | myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia 3 | 6.43e−03 | −1.20 | 4.51e−02 | −1.12 |

| 212293_at | HIPK1 | homeodomain interacting protein kinase 1 | 1.26e−02 | −1.20 | 3.09e−03 | −1.12 |

| 213579_s_at | EP300 | E1A binding protein p300 | 2.76e−02 | −1.18 | 2.16e−02 | −1.14 |

| 229723_at | TAGAP | T-cell activation RhoGTPase activating protein | 1.09e−02 | −1.22 | 1.23e−02 | −1.11 |

| 1568764_x_at | LOC728613/PDCD6 | programmed cell death 6 pseudogene/programmed cell death 6 | 4.33e−02 | −1.17 | 2.82e−02 | −1.17 |

| 217745_s_at | NAT13 | N-acetyltransferase 13 (GCN5-related) | 2.21e−03 | −1.24 | 3.60e−02 | −1.11 |

| 1552426_a_at | TM2D3 | TM2 domain containing 3 | 2.73e−02 | −1.23 | 2.12e−02 | −1.12 |

| 208583_x_at | HIST1H2AJ | histone cluster 1, H2aj | 2.92e−02 | −1.21 | 3.14e−02 | −1.14 |

| 209001_s_at | ANAPC13 | anaphase promoting complex subunit 13 | 4.36e−04 | −1.26 | 1.76e−02 | −1.10 |

| 224315_at | DDX20 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 20 | 3.86e−02 | −1.21 | 4.19e−02 | −1.16 |

| 226565_at | TMEM99 | transmembrane protein 99 | 2.73e−02 | −1.22 | 3.18e−02 | −1.15 |

| 209606_at | CYTIP | cytohesin 1 interacting protein | 1.61e−02 | −1.25 | 3.12e−02 | −1.12 |

| 212665_at | TIPARP | TCDD-inducible poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase | 1.55e−02 | −1.24 | 4.61e−02 | −1.12 |

| 217814_at | CCDC47 | coiled-coil domain containing 47 | 2.67e−03 | −1.24 | 5.08e−03 | −1.15 |

| 225133_at | KLF3 | Kruppel-like factor 3 (basic) | 1.72e−03 | −1.24 | 1.36e−03 | −1.16 |

| 209187_at | DR1 | down-regulator of transcription 1, TBP-binding (negative cofactor 2) | 1.65e−02 | −1.24 | 1.28e−02 | −1.16 |

| 223939_at | SUCNR1 | succinate receptor 1 | 1.22e−02 | −1.23 | 1.34e−03 | −1.19 |

| 209433_s_at | PPAT | phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate amidotransferase | 1.39e−02 | −1.28 | 3.50e−02 | −1.14 |

| 1569349_at | C11orf30 | chromosome 11 open reading frame 30 | 4.89e−04 | −1.33 | 3.18e−02 | −1.10 |

| 214331_at | TSFM | Ts translation elongation factor, mitochondrial | 2.86e−02 | −1.25 | 3.21e−02 | −1.22 |

| 227137_at | LOC100292024 | hypothetical protein LOC100292024 | 5.39e−03 | −1.30 | 3.21e−02 | −1.17 |

| 228749_at | ZDBF2 | zinc finger, DBF-type containing 2 | 6.61e−03 | −1.29 | 2.83e−03 | −1.19 |

| 226731_at | PELO | Pelota homolog (Drosophila) | 1.89e−02 | −1.30 | 3.62e−02 | −1.17 |

| 223809_at | RGS18 | regulator of G-protein signaling 18 | 3.41e−02 | −1.31 | 2.79e−02 | −1.19 |

| 205857_at | SLC18A2 | solute carrier family 18 (vesicular monoamine), member 2 | 3.53e−03 | −1.35 | 3.46e−02 | −1.16 |

| 212930_at | ATP2B1 | ATPase, Ca++ transporting, plasma membrane 1 | 1.13e−02 | −1.34 | 1.42e−02 | −1.17 |

| 222067_x_at | HIST1H2BD | histone cluster 1, H2bd | 4.38e−02 | −1.34 | 4.05e−02 | −1.21 |

| 215071_s_at | HIST1H2AC | histone cluster 1, H2ac | 8.26e−03 | −1.36 | 3.14e−03 | −1.19 |

| 222642_s_at | TMEM33 | transmembrane protein 33 | 3.09e−02 | −1.32 | 2.79e−02 | −1.24 |

| 238462_at | UBASH3B | ubiquitin associated and SH3 domain containing, B | 3.68e−03 | −1.39 | 1.49e−02 | −1.17 |

| 205072_s_at | XRCC4 | X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 4 | 4.17e−03 | −1.37 | 1.71e−02 | −1.20 |

| 218446_s_at | FAM18B | family with sequence similarity 18, member B | 1.22e−02 | −1.35 | 2.99e−03 | −1.24 |

| 208523_x_at | HIST1H2BI | histone cluster 1, H2bi | 2.82e−02 | −1.37 | 2.78e−02 | −1.23 |

| 208490_x_at | HIST1H2BF | histone cluster 1, H2bf | 2.66e−02 | −1.39 | 3.74e−02 | −1.22 |

| 208546_x_at | HIST1H2BH | histone cluster 1, H2bh | 3.38e−02 | −1.38 | 4.47e−02 | −1.24 |

| 1554544_a_at | MBP | myelin basic protein | 2.67e−02 | −1.40 | 2.79e−02 | −1.29 |

| 1562321_at | PDK4 | pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 4 | 2.79e−02 | −1.44 | 2.51e−02 | −1.34 |

| 210136_at | MBP | myelin basic protein | 1.45e−02 | −1.47 | 1.12e−02 | −1.33 |

| 214469_at | HIST1H2AE | histone cluster 1, H2ae | 2.46e−02 | −1.53 | 6.60e−03 | −1.41 |

| 202708_s_at | HIST2H2BE | histone cluster 2, H2be | 2.18e−02 | −1.58 | 1.93e−03 | −1.45 |

| 221958_s_at | GPR177 | G protein-coupled receptor 177 | 3.38e−02 | −1.90 | 3.64e−02 | −1.49 |

| 241403_at | CLK4 | CDC-like kinase 4 | 3.04e−02 | −1.96 | 4.12e−02 | −1.50 |

Rows are sorted by average fold-change in the SZ and SIB groups compared to the CCS group, with largest positive fold-change at the top and largest negative fold-change at the bottom of the Table.

The list of 168 known transcripts (represented by the 172 known probes) dysregulated in both SZs and SIBs compared to CCSs was enriched with genes that represented various functional categories, ontologies, pathways, and protein domains. Those terms that surpassed a Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significant enrichment (α=0.05/number of terms evaluated in a particular category) are shown in Table 2. Notably, six of the seven significantly enriched terms represented histone- and nucleosome-related functions, ontologies, or protein domains.

Table 2.

Functional Categories, Ontologies, Pathways, and Protein Domains Significantly Over-Represented Among Genes Significantly Dysregulated in both the SZ and SIB Groups Compared to the CCS Group

| Domain | Category | Term | Genes on List |

n (%) of Genes on List |

Fold- Enrichment |

p | Bonferroni- corrected p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Category | PIR Keywords | nucleosome core |

HIST1H2AC HIST1H2AE HIST1H2BD HIST1H2BF/I HIST2H2BE HIST1H2BH |

6 (3.7) | 19.9 | 1.14e−05 | 2.89e−03 |

| Ontology | Cellular Component | nucleosome |

HIST1H2AC HIST1H2BD HIST2H2BE HIST1H2BF/I HIST1H2AE HIST1H2BH |

6 (3.7) | 14.0 | 6.15e−05 | 1.43e−02 |

| Pathway | KEGG Pathway | systemic lupus erythematosus |

HLA-DQB1 HIST1H2AC HIST1H2BD HIST2H2BE HIST1H2BF/I HIST1H2AE HIST1H2BH HLA-DMB HLA-DMA |

9 (5.6) | 11.5 | 6.25e−07 | 4.44e−05 |

| Protein Domain | InterPro Domain | histone core |

HIST1H2AC HIST1H2BD HIST2H2BE HIST1H2BF/I HIST1H2AE HIST1H2BH |

6 (3.7) | 20.1 | 1.05e−05 | 3.82e−03 |

| InterPro Domain | histone fold |

HIST1H2BD HIST2H2BE HIST1H2BF/I DR1 HIST1H2AE HIST1H2BH |

6 (3.7) | 14.6 | 5.30e−05 | 1.91e−02 | |

| PIR Superfamily | Histone H2B |

HIST1H2BD HIST2H2BE HIST1H2BF/I HIST1H2BH |

4 (2.5) | 33.3 | 1.89e−04 | 1.31e−02 | |

| SMART Domain | H2B |

HIST1H2BD HIST2H2BE HIST1H2BF/I HIST1H2BH |

4 (2.5) | 33.7 | 1.89e−04 | 1.71e−02 | |

[SZ vs. CCS] ∩ [SZ vs. SIB]

Compared to both the CCS and SIB groups, SZ subjects showed significant evidence (p<0.05 in both comparisons) of common dysregulation of 96 probes for 94 known transcripts (Table 3). Two of these genes (PPM1A and RAPGEF2) were each tagged by two probes that were dysregulated in SZs compared to both SIBs and CCSs. The majority of changes observed in SZs were in the same direction vis-à-vis both SIBs and CCSs. Fifty-one probes were down-regulated and 37 probes were up-regulated in SZs compared to both groups; six probes were up-regulated in SZs compared to SIBs but down-regulated in SZs compared to CCSs; and two probes were down-regulated in SZs compared to SIBs but up-regulated in SZs compared to CCSs.

Table 3.

Genes Significantly Dysregulated in the SZ Group Compared to Both SIB and CCS Groups1

| Probeset ID |

Gene Symbol |

Gene Product |

SZ vs. CCS | SZ vs. SIB | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | Fold-Change | p | Fold-Change | |||

| 201050_at | PLD3 | phospholipase D family, member 3 | 2.81e−02 | 1.29 | 4.85e−02 | 1.32 |

| 242663_at | LOC148189 | Hypothetical LOC148189 | 1.78e−02 | 1.13 | 5.09e−03 | 1.29 |

| 205618_at | PRRG1 | proline rich Gla (G-carboxyglutamic acid) 1 | 2.73e−02 | 1.17 | 4.04e−02 | 1.22 |

| 244597_at | LOC26010 | Viral DNA polymerase-transactivated protein 6 | 1.62e−02 | 1.16 | 4.78e−02 | 1.22 |

| 214612_x_at | MAGEA6 | melanoma antigen family A, 6 | 1.74e−02 | 1.15 | 7.10e−03 | 1.21 |

| 207325_x_at | MAGEA1 | melanoma antigen family A, 1 (directs expression of antigen MZ2-E) | 4.24e−02 | 1.15 | 2.24e−03 | 1.20 |

| 207773_x_at | CYP3A43 | cytochrome P450, family 3, subfamily A, polypeptide 43 | 4.99e−02 | 1.13 | 1.08e−02 | 1.22 |

| 243570_at | SPCS2 | signal peptidase complex subunit 2 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | 1.42e−02 | 1.19 | 3.38e−02 | 1.15 |

| 1561378_at | C12orf42 | chromosome 12 open reading frame 42 | 2.75e−02 | 1.13 | 7.26e−03 | 1.21 |

| 205447_s_at | MAP3K12 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 12 | 1.20e−02 | 1.18 | 3.12e−02 | 1.15 |

| 1560432_at | CLRN1OS | clarin 1 opposite strand | 3.43e−02 | 1.14 | 9.10e−03 | 1.18 |

| 209842_at | SOX10 | SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 10 | 1.37e−02 | 1.16 | 3.44e−02 | 1.16 |

| 1570128_at | DDX19A | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-As) box polypeptide 19A | 3.47e−02 | 1.13 | 4.53e−02 | 1.17 |

| 236688_at | FRMPD3 | FERM and PDZ domain containing 3 | 3.73e−02 | 1.14 | 2.61e−02 | 1.16 |

| 1553746_a_at | C12orf64 | chromosome 12 open reading frame 64 | 8.03e−04 | 1.15 | 2.04e−03 | 1.13 |

| 219699_at | LGI2 | leucine-rich repeat LGI family, member 2 | 3.88e−02 | 1.14 | 1.62e−02 | 1.14 |

| 1561332_at | ATP13A5 | ATPase type 13A5 | 7.05e−03 | 1.15 | 1.84e−02 | 1.12 |

| 1559459_at | LOC613266 | hypothetical LOC613266 | 3.48e−02 | 1.14 | 9.74e−03 | 1.12 |

| 231994_at | CHDH | choline dehydrogenase | 4.21e−03 | 1.16 | 4.97e−04 | 1.10 |

| 242301_at | CBLN2 | cerebellin 2 precursor | 2.12e−03 | 1.15 | 2.41e−02 | 1.10 |

| 231155_at | DEFB119 | defensin, beta 119 | 1.05e−02 | 1.13 | 4.60e−02 | 1.12 |

| 204796_at | EML1 | echinoderm microtubule associated protein like 1 | 3.31e−02 | 1.11 | 2.68e−03 | 1.13 |

| 236730_at | GIPC3 | GIPC PDZ domain containing family, member 3 | 2.37e−02 | 1.13 | 4.01e−02 | 1.11 |

| 213209_at | TAF6L | TAF6-like RNA polymerase II, p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF)-associated factor | 1.59e−02 | 1.11 | 1.16e−02 | 1.13 |

| 238262_at | SPDYA | speedy homolog A (Xenopus laevis) | 2.92e−02 | 1.15 | 3.30e−02 | 1.09 |

| 1552458_at | MBD3L1 | methyl-CpG binding domain protein 3-like 1 | 2.52e−02 | 1.13 | 4.65e−02 | 1.10 |

| 222328_x_at | MEG3 | Maternally expressed 3 (non-protein coding) | 4.38e−02 | 1.11 | 2.30e−02 | 1.12 |

| 1562271_x_at | ARHGEF7 | Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 7 | 4.24e−02 | 1.11 | 1.20e−02 | 1.12 |

| 218182_s_at | CLDN1 | claudin 1 | 2.47e−02 | 1.10 | 3.75e−02 | 1.12 |

| 220771_at | LOC51152 | melanoma antigen | 7.99e−03 | 1.11 | 4.75e−03 | 1.11 |

| 230394_at | TCP10L | t-complex 10 (mouse)-like | 7.80e−03 | 1.13 | 1.77e−02 | 1.08 |

| 204235_s_at | GULP1 | GULP, engulfment adaptor PTB domain containing 1 | 2.18e−02 | 1.09 | 1.64e−02 | 1.10 |

| 232424_at | PRDM16 | PR domain containing 16 | 4.27e−02 | 1.12 | 1.79e−02 | 1.07 |

| 221177_at | MIA2 | melanoma inhibitory activity 2 | 3.56e−02 | 1.12 | 1.01e−02 | 1.07 |

| 206858_s_at | HOXC6 | homeobox C6 | 4.14e−02 | 1.11 | 4.37e−02 | 1.08 |

| 1566734_at | LOC283454 | hypothetical protein LOC283454 | 4.79e−02 | 1.10 | 1.80e−02 | 1.08 |

| 1557312_at | C12orf61 | chromosome 12 open reading frame 61 | 9.72e−03 | 1.10 | 2.55e−02 | 1.07 |

| 244344_at | WNK4 | WNK lysine deficient protein kinase 4 | 5.32e−03 | 1.25 | 4.23e−02 | −1.16 |

| 1562048_at | LOC152225 | hypothetical LOC152225 | 8.37e−03 | 1.12 | 3.74e−02 | −1.08 |

| 1568764_x_at | LOC728613/PDCD6 | programmed cell death 6 pseudogene/programmed cell death 6 | 4.33e−02 | −1.17 | 2.93e−02 | 1.21 |

| 214331_at | TSFM | Ts translation elongation factor, mitochondrial | 2.86e−02 | −1.25 | 2.97e−02 | 1.28 |

| 238923_at | SPOP | speckle-type POZ protein | 2.08e−02 | −1.15 | 1.98e−02 | 1.16 |

| 201111_at | CSE1L | CSE1 chromosome segregation 1-like (yeast) | 4.71e−03 | −1.32 | 2.27e−02 | 1.27 |

| 236026_at | GPATCH2 | G patch domain containing 2 | 1.46e−02 | −1.20 | 8.24e−03 | 1.14 |

| 230954_at | C20orf112 | chromosome 20 open reading frame 112 | 2.02e−03 | −1.17 | 1.40e−02 | 1.12 |

| 203605_at | SRP54 | signal recognition particle 54kDa | 4.69e−02 | −1.08 | 3.43e−02 | −1.10 |

| 218241_at | GOLGA5 | golgi autoantigen, golgin subfamily a, 5 | 2.75e−02 | −1.11 | 4.79e−02 | −1.08 |

| 217877_s_at | GPBP1L1 | GC-rich promoter binding protein 1-like 1 | 3.18e−02 | −1.11 | 1.89e−02 | −1.13 |

| 201371_s_at | CUL3 | cullin 3 | 3.58e−03 | −1.15 | 4.07e−02 | −1.12 |

| 202209_at | LSM3 | LSM3 homolog, U6 small nuclear RNA associated (S. cerevisiae) | 1.41e−02 | −1.16 | 4.79e−02 | −1.12 |

| 209326_at | SLC35A2 | solute carrier family 35 (UDP-galactose transporter), member A2 | 4.99e−02 | −1.13 | 1.89e−02 | −1.15 |

| 200066_at | IK | IK cytokine, down-regulator of HLA II | 8.39e−03 | −1.14 | 1.70e−02 | −1.15 |

| 220958_at | ULK4 | unc-51-like kinase 4 (C. elegans) | 2.51e−02 | −1.12 | 2.70e−02 | −1.17 |

| 225268_at | KPNA4 | karyopherin alpha 4 (importin alpha 3) | 2.36e−02 | −1.17 | 2.85e−02 | −1.13 |

| 218171_at | VPS4B | vacuolar protein sorting 4 homolog B (S. cerevisiae) | 3.90e−02 | −1.14 | 3.76e−02 | −1.16 |

| 226648_at | HIF1AN | hypoxia inducible factor 1, alpha subunit inhibitor | 2.02e−02 | −1.19 | 1.88e−02 | −1.11 |

| 209986_at | ASCL1 | achaete-scute complex homolog 1 (Drosophila) | 4.17e−02 | −1.13 | 4.32e−02 | −1.18 |

| 227357_at | MAP3K7IP3 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 interacting protein 3 | 3.58e−02 | −1.14 | 1.62e−02 | −1.18 |

| 57703_at | SENP5 | SUMO1/sentrin specific peptidase 5 | 3.65e−03 | −1.17 | 3.98e−03 | −1.15 |

| 209463_s_at | TAF12 | TAF12 RNA polymerase II, TATA box binding protein (TBP)-associated factor, 20kDa | 4.93e−02 | −1.11 | 1.65e−02 | −1.21 |

| 201099_at | USP9X | ubiquitin specific peptidase 9, X-linked | 2.47e−03 | −1.17 | 2.16e−02 | −1.16 |

| 226952_at | EAF1 | ELL associated factor 1 | 6.68e−03 | −1.18 | 4.81e−02 | −1.15 |

| 1554351_a_at | TIPRL | TIP41, TOR signaling pathway regulator-like (S. cerevisiae) | 1.41e−02 | −1.15 | 3.91e−02 | −1.19 |

| 218761_at | RNF111 | ring finger protein 111 | 4.01e−02 | −1.18 | 5.00e−04 | −1.16 |

| 202352_s_at | PSMD12 | proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, non-ATPase, 12 | 3.95e−02 | −1.12 | 1.81e−02 | −1.22 |

| 212665_at | TIPARP | TCDD-inducible poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase | 1.55e−02 | −1.24 | 3.29e−02 | −1.11 |

| 200071_at | SMNDC1 | survival motor neuron domain containing 1 | 2.95e−03 | −1.19 | 4.83e−02 | −1.17 |

| 224974_at | SUDS3 | suppressor of defective silencing 3 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | 2.08e−02 | −1.24 | 3.64e−02 | −1.12 |

| 217795_s_at | TMEM43 | transmembrane protein 43 | 3.01e−02 | −1.17 | 2.57e−02 | −1.20 |

| 214865_at | DOT1L | DOT1-like, histone H3 methyltransferase (S. cerevisiae) | 4.06e−02 | −1.19 | 7.84e−03 | −1.21 |

| 223288_at | USP38 | ubiquitin specific peptidase 38 | 4.70e−02 | −1.17 | 4.70e−02 | −1.24 |

| 221873_at | ZNF143 | zinc finger protein 143 | 2.90e−02 | −1.16 | 1.19e−02 | −1.26 |

| 221244_s_at | PDPK1 | 3-phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase-1 | 3.18e−02 | −1.18 | 4.06e−02 | −1.25 |

| 204507_s_at | PPP3R1 | protein phosphatase 3 (formerly 2B), regulatory subunit B, alpha isoform | 2.53e−02 | −1.22 | 4.47e−02 | −1.20 |

| 227413_at | UBLCP1 | ubiquitin-like domain containing CTD phosphatase 1 | 4.25e−02 | −1.15 | 7.16e−03 | −1.27 |

| 231588_at | PRCP | Prolylcarboxypeptidase (angiotensinase C) | 4.91e−04 | −1.29 | 2.09e−02 | −1.15 |

| 222432_s_at | CCDC47 | coiled-coil domain containing 47 | 1.26e−03 | −1.17 | 6.55e−03 | −1.28 |

| 204513_s_at | ELMO1 | engulfment and cell motility 1 | 2.05e−02 | −1.18 | 4.41e−02 | −1.27 |

| 218668_s_at | RAP2C | RAP2C, member of RAS oncogene family | 2.05e−02 | −1.24 | 1.65e−02 | −1.22 |

| 231640_at | LYRM5 | LYR motif containing 5 | 5.58e−03 | −1.29 | 1.44e−02 | −1.21 |

| 202539_s_at | HMGCR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A reductase | 1.82e−02 | −1.26 | 4.25e−02 | −1.30 |

| 33494_at | ETFDH | electron-transferring-flavoprotein dehydrogenase | 1.89e−02 | −1.31 | 3.82e−02 | −1.26 |

| 212585_at | OSBPL8 | oxysterol binding protein-like 8 | 4.07e−02 | −1.23 | 4.47e−02 | −1.34 |

| 219532_at | ELOVL4 | elongation of very long chain fatty acids (FEN1/Elo2, SUR4/Elo3, yeast)-like 4 | 1.55e−02 | −1.37 | 2.24e−02 | −1.22 |

| 223809_at | RGS18 | regulator of G-protein signaling 18 | 3.41e−02 | −1.31 | 7.82e−04 | −1.31 |

| 1554588_a_at | TTC30B | tetratricopeptide repeat domain 30B | 4.70e−02 | −1.23 | 2.63e−03 | −1.39 |

| 229027_at | PPM1A | protein phosphatase 1A (formerly 2C), magnesium-dependent, alpha isoform | 1.75e−02 | −1.32 | 6.14e−03 | −1.30 |

| 202006_at | PTPN12 | protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 12 | 2.32e−02 | −1.30 | 3.82e−02 | −1.33 |

| 227728_at | PPM1A | protein phosphatase 1A (formerly 2C), magnesium-dependent, alpha isoform | 3.14e−02 | −1.24 | 2.86e−02 | −1.40 |

| 225598_at | SLC45A4 | solute carrier family 45, member 4 | 4.87e−02 | −1.44 | 4.17e−02 | −1.31 |

| 203097_s_at | RAPGEF2 | Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 2 | 7.51e−03 | −1.46 | 4.33e−02 | −1.31 |

| 215071_s_at | HIST1H2AC | histone cluster 1, H2ac | 8.26e−03 | −1.36 | 1.61e−02 | −1.43 |

| 226106_at | RNF141 | ring finger protein 141 | 2.29e−02 | −1.30 | 1.85e−02 | −1.53 |

| 217494_s_at | LOC100290144 | hypothetical protein LOC100290144 | 1.31e−02 | −1.39 | 5.66e−03 | −1.57 |

| 240744_at | CPA5 | carboxypeptidase A5 | 1.09e−02 | −1.65 | 2.42e−02 | −1.37 |

| 203096_s_at | RAPGEF2 | Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 2 | 4.80e−02 | −1.54 | 1.47e−02 | −1.75 |

Rows are sorted by average fold-change in the SZ group compared to SIB and CCS groups, with largest positive fold-change at the top and largest negative fold-change at the bottom of the Table.

The list of 94 known transcripts (represented by the 96 known probes) dysregulated in SZs compared to both SIBs and CCSs was enriched at a nominal level of significance with genes that represented various functional categories, pathways, ontologies, and protein domains; however, none of these terms surpassed a Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significant enrichment (α=0.05/number of terms evaluated in a particular category).

[SIB vs. SZ] ∩ [SIB vs. CCS]

Compared to both the CCS and SZ groups, SIBs showed significant evidence (p<0.05 in both comparisons) of common dysregulation of 82 probes for 81 known transcripts (Table 4). One of these genes (ZNF81) was tagged by two probes that were dysregulated in SIBs compared to both SZs and CCSs. The majority of changes observed in SIBs were in the same direction vis-à-vis both SZs and CCSs. Forty-nine probes were up-regulated and 22 probes were down-regulated in SIBs compared to both groups; seven probes were down-regulated in SIBs compared to CCSs but up-regulated in SIBs compared to SZs; and four probes were up-regulated in SIBs compared to CCSs but down-regulated in SIBs compared to SZs.

Table 4.

Genes Significantly Dysregulated in the SIB Group Compared to Both SZ and CCS Groups1

| Probeset ID |

Gene Symbol |

Gene Product |

SIB vs. CCS | SIB vs. SZ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | Fold-Change | p | Fold-Change | |||

| 210233_at | IL1RAP | interleukin 1 receptor accessory protein | 1.66e−02 | 1.50 | 2.17e−05 | 2.06 |

| 232197_x_at | ARSB | arylsulfatase B | 4.03e−02 | 1.24 | 4.94e−02 | 1.58 |

| 217222_at | IGHG1 | Immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 1 (G1m marker) | 1.58e−02 | 1.17 | 4.75e−02 | 1.27 |

| 1569076_a_at | ZNF836 | zinc finger protein 836 | 3.17e−02 | 1.17 | 3.49e−02 | 1.23 |

| 227777_at | C10orf18 | chromosome 10 open reading frame 18 | 2.14e−02 | 1.15 | 1.10e−02 | 1.23 |

| 236246_x_at | LOC653160 | Hypothetical protein LOC653160 | 2.89e−02 | 1.14 | 4.20e−02 | 1.23 |

| 220894_x_at | PRDM12 | PR domain containing 12 | 6.27e−03 | 1.17 | 2.11e−02 | 1.20 |

| 205925_s_at | RAB3B | RAB3B, member RAS oncogene family | 1.72e−02 | 1.13 | 5.90e−03 | 1.22 |

| 239356_at | LOC100129122 | Hypothetical protein LOC100129122 | 4.22e−02 | 1.10 | 4.93e−02 | 1.24 |

| 211403_x_at | VCX2 | variable charge, X-linked 2 | 1.26e−03 | 1.16 | 1.24e−02 | 1.17 |

| 223895_s_at | EPN3 | epsin 3 | 1.62e−03 | 1.19 | 1.59e−02 | 1.14 |

| 237095_at | ASXL2 | additional sex combs like 2 (Drosophila) | 8.40e−04 | 1.17 | 3.46e−02 | 1.14 |

| 244344_at | WNK4 | WNK lysine deficient protein kinase 4 | 3.19e−02 | 1.15 | 4.23e−02 | 1.16 |

| 230217_at | RLBP1L1 | retinaldehyde binding protein 1-like 1 | 9.71e−03 | 1.15 | 4.34e−02 | 1.15 |

| 214197_s_at | SETDB1 | SET domain, bifurcated 1 | 1.37e−02 | 1.11 | 1.96e−02 | 1.19 |

| 219465_at | APOA2 | apolipoprotein A-II | 4.15e−02 | 1.10 | 1.09e−02 | 1.19 |

| 236150_at | AGPHD1 | aminoglycoside phosphotransferase domain containing 1 | 1.73e−02 | 1.13 | 3.59e−02 | 1.15 |

| 222092_at | PTPN21 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 21 | 2.48e−02 | 1.10 | 3.18e−02 | 1.18 |

| 206586_at | CNR2 | cannabinoid receptor 2 (macrophage) | 3.62e−02 | 1.08 | 6.81e−03 | 1.19 |

| 232393_at | ZNF462 | zinc finger protein 462 | 4.56e−02 | 1.08 | 9.47e−04 | 1.18 |

| 217675_at | ZBTB7C | zinc finger and BTB domain containing 7C | 1.73e−02 | 1.10 | 3.59e−03 | 1.16 |

| 1561039_a_at | ZNF81 | zinc finger protein 81 | 6.86e−03 | 1.10 | 1.52e−02 | 1.16 |

| 205150_s_at | TRIL | TLR4 interactor with leucine rich repeats | 5.21e−03 | 1.10 | 2.40e−06 | 1.16 |

| 238280_at | CYB5RL | cytochrome b5 reductase-like | 1.23e−02 | 1.12 | 2.62e−02 | 1.14 |

| 207465_at | PRO0628 | uncharacterized protein PRO0628-like | 2.51e−02 | 1.05 | 1.94e−02 | 1.20 |

| 218549_s_at | FAM82B | family with sequence similarity 82, member B | 1.02e−02 | 1.12 | 4.63e−02 | 1.13 |

| 210820_x_at | COQ7 | coenzyme Q7 homolog, ubiquinone (yeast) | 3.26e−02 | 1.10 | 5.60e−03 | 1.14 |

| 230908_at | TACR1 | tachykinin receptor 1 | 4.81e−02 | 1.06 | 3.50e−04 | 1.18 |

| 233368_s_at | DNAJC27 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 27 | 1.90e−03 | 1.11 | 1.36e−02 | 1.13 |

| 228651_at | VWA1 | von Willebrand factor A domain containing 1 | 1.00e−02 | 1.11 | 3.12e−02 | 1.13 |

| 238925_at | SNTB2 | syntrophin, beta 2 (dystrophin-associated protein A1, 59kDa, basic component 2) | 3.97e−02 | 1.10 | 3.18e−02 | 1.13 |

| 229839_at | SCARA5 | Scavenger receptor class A, member 5 (putative) | 3.24e−02 | 1.09 | 3.35e−02 | 1.13 |

| 1559342_a_at | SNRPN | small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptide N | 2.76e−02 | 1.07 | 1.32e−02 | 1.15 |

| 1555774_at | ZAR1 | zygote arrest 1 | 1.81e−02 | 1.09 | 1.88e−02 | 1.13 |

| 1560692_at | LOC285878 | hypothetical protein LOC285878 | 3.54e−02 | 1.07 | 4.98e−02 | 1.14 |

| 1562675_at | LOC100128003 | hypothetical protein LOC100128003 | 3.04e−02 | 1.07 | 2.50e−02 | 1.14 |

| 230819_at | FAM148C | family with sequence similarity 148, member C | 2.30e−02 | 1.06 | 3.21e−03 | 1.13 |

| 231783_at | CHRM1 | cholinergic receptor, muscarinic 1 | 2.61e−02 | 1.09 | 1.42e−02 | 1.10 |

| 215721_at | IGHG1/LOC90925 | immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 1 (G1m marker)/hypothetical protein LOC9 | 6.52e−03 | 1.09 | 3.65e−02 | 1.10 |

| 1569729_a_at | ASZ1 | ankyrin repeat, SAM and basic leucine zipper domain containing 1 | 8.13e−04 | 1.10 | 2.39e−02 | 1.09 |

| 1562876_s_at | LOC541471 | Hypothetical LOC541471 | 1.04e−02 | 1.06 | 1.12e−02 | 1.12 |

| 1563223_a_at | CENPI | centromere protein I | 4.69e−02 | 1.08 | 3.99e−02 | 1.10 |

| 210035_s_at | RPL5/SNORA66 | ribosomal protein L5/small nucleolar RNA, H/ACA box 66 | 4.67e−02 | 1.06 | 4.04e−02 | 1.12 |

| 208416_s_at | SPTB | spectrin, beta, erythrocytic | 4.42e−02 | 1.07 | 3.39e−02 | 1.10 |

| 215655_at | GRIK2 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, kainate 2 | 5.46e−03 | 1.06 | 1.94e−02 | 1.11 |

| 204189_at | RARG | retinoic acid receptor, gamma | 2.38e−02 | 1.10 | 4.65e−02 | 1.07 |

| 240079_at | ZNF81 | Zinc finger protein 81 | 2.46e−02 | 1.07 | 1.45e−02 | 1.08 |

| 236967_at | LOC645249 | hypothetical protein LOC645249 | 2.18e−02 | 1.07 | 4.43e−02 | 1.08 |

| 1561137_s_at | GYPE | glycophorin E | 4.65e−02 | 1.05 | 4.20e−05 | 1.08 |

| 215071_s_at | HIST1H2AC | histone cluster 1, H2ac | 3.14e−03 | −1.19 | 1.61e−02 | 1.43 |

| 229090_at | LOC220930 | hypothetical LOC220930 | 4.27e−02 | −1.22 | 1.08e−02 | 1.43 |

| 223809_at | RGS18 | regulator of G-protein signaling 18 | 2.79e−02 | −1.19 | 7.82e−04 | 1.31 |

| 235012_at | LRCH1 | leucine-rich repeats and calponin homology (CH) domain containing 1 | 1.27e−02 | 1.20 | 4.44e−02 | −1.09 |

| 200071_at | SMNDC1 | survival motor neuron domain containing 1 | 2.92e−02 | −1.09 | 4.83e−02 | 1.17 |

| 205307_s_at | KMO | kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (kynurenine 3-hydroxylase) | 4.53e−02 | 1.18 | 5.78e−03 | −1.14 |

| 200620_at | TMEM59 | transmembrane protein 59 | 3.98e−02 | −1.09 | 3.41e−02 | 1.13 |

| 201580_s_at | TMX4 | thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein 4 | 4.14e−03 | −1.26 | 3.13e−02 | 1.29 |

| 230784_at | PRAC | prostate cancer susceptibility candidate | 3.99e−03 | 1.11 | 3.99e−02 | −1.09 |

| 212665_at | TIPARP | TCDD-inducible poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase | 4.61e−02 | −1.12 | 3.29e−02 | 1.11 |

| 1570128_at | DDX19A | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-As) box polypeptide 19A | 1.71e−02 | 1.10 | 4.53e−02 | −1.17 |

| 205669_at | NCAM2 | neural cell adhesion molecule 2 | 2.85e−02 | −1.09 | 2.71e−02 | −1.09 |

| 236034_at | ANGPT2 | angiopoietin 2 | 2.14e−02 | −1.09 | 4.44e−02 | −1.09 |

| 230057_at | LOC285178 | hypothetical protein LOC285178 | 2.93e−02 | −1.09 | 1.80e−02 | −1.11 |

| 221594_at | C7orf64 | chromosome 7 open reading frame 64 | 3.52e−02 | −1.09 | 1.24e−02 | −1.11 |

| 210906_x_at | AQP4 | aquaporin 4 | 7.50e−03 | −1.07 | 1.80e−02 | −1.13 |

| 1554932_at | ZSWIM2 | zinc finger, SWIM-type containing 2 | 2.49e−02 | −1.07 | 3.95e−02 | −1.14 |

| 230957_at | PCDHB19P | Protocadherin beta 19 pseudogene | 3.49e−02 | −1.08 | 8.23e−03 | −1.14 |

| 244822_at | GART | Phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase | 1.60e−02 | −1.06 | 1.46e−02 | −1.15 |

| 241604_at | ATP11A | ATPase, class VI, type 11A | 2.75e−02 | −1.06 | 3.11e−02 | −1.17 |

| 233141_s_at | ST7L | suppression of tumorigenicity 7 like | 3.87e−02 | −1.06 | 1.25e−02 | −1.18 |

| 233082_at | ZNF630 | zinc finger protein 630 | 1.49e−02 | −1.10 | 2.12e−02 | −1.15 |

| 215366_at | SNX13 | sorting nexin 13 | 1.53e−02 | −1.15 | 3.08e−02 | −1.11 |

| 1568663_a_at | PWRN2 | Prader-Willi region non-protein coding RNA 2 | 2.04e−02 | −1.09 | 1.01e−02 | −1.18 |

| 210315_at | SYN2 | synapsin II | 2.02e−02 | −1.10 | 3.06e−02 | −1.17 |

| 231130_at | FKBP7 | FK506 binding protein 7 | 3.44e−02 | −1.08 | 2.09e−02 | −1.20 |

| 211722_s_at | HDAC6 | histone deacetylase 6 | 3.11e−02 | −1.09 | 1.50e−02 | −1.20 |

| 221424_s_at | OR51E2 | olfactory receptor, family 51, subfamily E, member 2 | 1.39e−02 | −1.14 | 2.44e−02 | −1.15 |

| 219617_at | C2orf34 | chromosome 2 open reading frame 34 | 4.15e−02 | −1.08 | 2.95e−02 | −1.23 |

| 1564000_at | ANKRD31 | ankyrin repeat domain 31 | 2.92e−03 | −1.16 | 4.96e−02 | −1.18 |

| 1568764_x_at | LOC728613/PDCD6 | programmed cell death 6 pseudogene/programmed cell death 6 | 2.82e−02 | −1.17 | 2.93e−02 | −1.21 |

| 214331_at | TSFM | Ts translation elongation factor, mitochondrial | 3.21e−02 | −1.22 | 2.97e−02 | −1.28 |

| 232281_at | LOC148189 | Hypothetical LOC148189 | 6.52e−03 | −1.12 | 1.48e−03 | −1.39 |

Rows are sorted by average fold-change in the SIB group compared to SZ and CCS groups, with largest positive fold-change at the top and largest negative fold-change at the bottom of the Table.

The list of 81 known transcripts (represented by the 82 known probes) dysregulated in SIBs compared to both SZs and CCSs was nominally significantly enriched with genes that represented various functional categories, pathways, ontologies, and protein domains; however, none of these terms surpassed a Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significant enrichment (α=0.05/number of terms evaluated in a particular category).

[SZ vs. CCS] ∩ [SZ vs. SIB] ∩ [SIB vs. CCS]

Eight probes for eight known transcripts were dysregulated in all three orthogonal comparisons of diagnostic groups (Table 5). Four transcripts (SMNDC1, TIPARP, HIST1H2AC, and RGS18) were expressed at intermediate levels in SIBs with highest expression in CCSs and lowest expression in SZ. Conversely, one transcript (DDX19A) that was intermediately expressed in SIBs had the highest expression level in SZs and the lowest expression level in CCSs. Two transcripts (LOC728613/PDCD6 and TSFM) had the lowest expression levels in SIBs, the highest expression levels in CCSs, and intermediate expression in SZs. The remaining transcript (WNK4) had its highest expression level in SIBs and lowest expression level in CCSs, with SZs exhibiting intermediate expression levels. These eight known transcripts were not enriched with genes that represented any functional categories, pathways, ontologies, and protein domains.

Table 5.

Genes Significantly Dysregulated between SZ, SIB, and CCS Groups

| Probeset ID |

Gene Symbol |

Gene Product |

SZ vs. CCS | SZ vs. SIB | SIB vs. CCS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | Fold-Change | p | Fold-Change | p | Fold-Change | |||

| 1570128_at | DDX19A | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-As) box polypeptide 19A | 3.47e−02 | 1.13 | 4.53e−02 | 1.17 | 1.71e−02 | 1.10 |

| 244344_at | WNK4 | WNK lysine deficient protein kinase 4 | 5.32e−03 | 1.25 | 4.23e−02 | −1.16 | 3.19e−02 | 1.15 |

| 1568764_x_at | LOC728613/PDCD6 | programmed cell death 6 pseudogene/programmed cell death 6 | 4.33e−02 | −1.17 | 2.93e−02 | 1.21 | 2.82e−02 | −1.17 |

| 214331_at | TSFM | Ts translation elongation factor, mitochondrial | 2.86e−02 | −1.25 | 2.97e−02 | 1.28 | 3.21e−02 | −1.22 |

| 212665_at | TIPARP | TCDD-inducible poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase | 1.55e−02 | −1.24 | 3.29e−02 | −1.11 | 4.61e−02 | 1.12 |

| 200071_at | SMNDC1 | survival motor neuron domain containing 1 | 2.95e−03 | −1.19 | 4.83e−02 | −1.17 | 2.92e−02 | −1.09 |

| 223809_at | RGS18 | regulator of G-protein signaling 18 | 3.41e−02 | −1.31 | 7.82e−04 | −1.31 | 2.79e−02 | −1.19 |

| 215071_s_at | HIST1H2AC | histone cluster 1, H2ac | 8.26e−03 | −1.36 | 1.61e−02 | −1.43 | 3.14e−03 | −1.19 |

Rows are sorted by average fold-change across all three comparisons, with largest positive fold-change at the top and largest negative fold-change at the bottom of the Table.

DISCUSSION

In the past five years, much work has been done to establish the validity of blood-based gene-expression signatures as a means of detecting meaningful biomarkers for neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, we (Glatt and others 2005a) and others (Sullivan and others 2006) have found a reasonable level of correspondence in gene expression levels between peripheral blood and various brain structures, including some relevant to schizophrenia such as dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Others have demonstrated the considerable heritability and temporal stability of gene expression levels in peripheral blood (Meaburn and others 2009). However, one problem that has consistently plagued this area of research has been the inability to determine if transcriptomic abnormalities reflect “trait” or “state” conditions due to the inherent confounds of comparing non-mentally ill individuals to individuals with schizophrenia who undergo psychopharmacotherapy and deal with a chronic debilitating disorder and its sequelae. A recent study by Takahashi et al. (Takahashi and others 2010) partially overcame this conundrum by studying antipsychotic-free schizophrenia patients; yet, while many of the subjects in this study were truly drug- or at least antipsychotic-naïve, others had previously been on antipsychotics as recently as eight weeks prior to testing, and some subjects were actively on other classes of drugs such as antidepressants, benzodiazepines, or mood stabilizers at the time of testing. The work of Takahashi et al. has markedly advanced the field by identifying profiles of as few as 14 probes that yielded 82.4% sensitivity and 93.8% specificity in classifying a separate set of schizophrenia patients and control subjects. However, because these patients had already been ill for some time, it remains unknown if the differences expressed in their peripheral blood transcriptomes were static markers of the underlying genetic susceptibility to the disorder or were consequences of their illness. In an attempt to further clarify the contributions of trait and state to peripheral blood transcriptomic abnormalities in schizophrenia, we have assessed biological siblings, who share both genetic and early environmental factors in common with their affected relatives. In addition to helping rule out various confounder effects as major drivers behind observed transcriptomic abnormalities in the patient population, the inclusion of relatives was also intended to shed light on potential protective factors operating to keep these genetically susceptible individuals from expressing the illness.

At the intersection of probes that were differentially expressed in the peripheral blood of both SZ and SIB groups relative to the CCS group, we found 168 commonly dysregulated genes which may reflect risk factors for SZ that are independent of illness-associated factors, such as chronic treatment with antipsychotic medication. One of these 168 commonly dysregulated genes, SPIRE1, was significantly dysregulated in both the SZ and SIB groups but in opposite directions, suggesting that up-regulation of this particular gene may be associated with some protective capacity among genetically susceptible individuals (SIBs). Collectively, these 168 commonly dysregulated genes contained an over-representation of genes related to histone and nucleosome function, ontology, and structure, suggesting that SZ may be associated with a global dysregulation of the histone system. Of note, in an early study, we showed that lysergic acid diethylamide, which can elicit psychotic symptoms, had effects on histone acetylation (Brown and Liew 1975). Histones are proteins around which nuclear double-stranded DNA is coiled, and the functionality of histones can be altered by post-translational modifications such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, citrullination and ADP-ribosylation. Such epigenetic modifications can influence the accessibility of the surrounding DNA leading to up- or down-regulation of the mRNA transcripts of genes in the vicinity of that modification. It is conceivable, therefore, that a singular abnormality or a collection of abnormalities (such as increased intensity of gene expression) leading to a common endpoint (e.g., histone dysfunction) in SZ and its genetically influenced risk state could lead to the consequent dysregulation of a whole host of other genes relevant to the development or presentation of the disorder.

In addition to gene-set enrichment analyses in DAVID, we compared this list of jointly dysregulated known transcripts to the list of 45 “Top Results” from the Schizophrenia Gene (SZGene) Database (Allen and others 2008) as of March 15, 2011, which collates the evidence from genetic association studies of schizophrenia and identifies which genes have significant meta-analytic evidence as risk factors for the disorder. Only one of the 45 Top Results from the SZGene database was also significantly dysregulated in both the SZ and SIB groups compared to the CCS group: DRD2, which was commonly up-regulated in the SZ and SIB groups. This result is strikingly similar to that of Zvara et al. (2005), who found up-regulation of DRD2 in peripheral blood from drug-naïve schizophrenia patients as well. Of course, the D2 dopamine receptor, which is encoded by this gene, is the major antagonistic target of all effective antipsychotic medications, and has been the protein around which the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia was built and modified over the course of the last four decades (Baumeister and Francis 2002; Seeman and others 2005; Van Rossum 1967). We and others have also found consistent evidence for association of polymorphisms in this gene with susceptibility to the disorder (Glatt and others 2009; Glatt and Jonsson 2006). Collectively, these findings suggest that variation in DRD2, particularly those modifications which result in over-expression of its transcript, are a trait marker of the liability toward schizophrenia, not a state marker or merely a response to treatment with D2 receptor antagonists.

We also performed a literature search in PubMed for keyword pairs of “schizophrenia” and the official gene symbol for each jointly dysregulated transcript, and found that, in addition to DRD2, several other genes that were on our list of 168 genes (Table 1) had been previously associated with the disorder in at least one other study. These genes included: 1) CACNA1C, which encodes a calcium channel and has been identified as a genome-wide significant risk factor for bipolar disorder (Ferreira and others 2008) and subsequently identified as a risk factor for SZ as well (Green and others 2009); 2) GNAS, which encodes an adenylate cyclase-stimulating G alpha protein and has been associated with deficit SZ (Minoretti and others 2006); 3) HLA-DQB1, which encodes a HLA class II histocompatibility antigen and has shown mixed (but mostly negative) evidence for association with the disorder across a number of studies (Nimgaonkar and others 1993; Nimgaonkar and others 1997; Schwab and others 2002); 4) HNRNPC, which encodes a heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein that was found to be down-regulated in SZ (as was its mRNA transcript in the present study) in postmortem left posterior superior temporal gyrus (Wernicke's area) (Martins-de-Souza and others 2009); 5) MBP, which encodes a myelin basic protein and is one of the most commonly observed dysregulated transcripts in functional genomic studies of postmortem brain tissue from SZ subjects (Segal and others 2007); 6) NPAS2, which encodes a transcription factor and putative circadian clock protein which has been associated with both SZ and bipolar disorder (Mansour and others 2009); 7) PER3, which encodes another circadian clock protein associated with SZ (Mansour and others 2006); 8) PICK1, which encodes a protein-kinase-C-alpha-interacting protein that was found to be up-regulated in SZ (as it was in the present study) in postmortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Sarras and others); and 9) SLC18A2, which encodes vesicular monoamine transporter 2 and has been associated with SZ (Talkowski and others 2008).

At the intersection of probes that were differentially expressed in the SZ group compared to both the SIB and CCS groups we found 94 jointly dysregulated genes whose up- or down-regulation may lead to SZ while typical levels of expression of these genes may spare the genetically susceptible SIBs from illness; however, these genes may also reflect the influence of environmental factors or non-genetic biological or developmental changes that are associated with the disorder. A third option is that such genes are induced by or responsive to pharmaco- or other therapies, or sequelae of the disorder, to which the SZ group was exclusively exposed.

We also observed a set of 82 transcripts that were dysregulated exclusively in unaffected SIBs and not altered in their affected biological relatives. In some instances, SIBs had expression levels that were intermediate to the two comparison groups (SZs and CCSs), suggestive of some illness-associated (possibly genetically influenced) risk genes whose level of expression is associated with the likelihood of expressing the disorder. In other words, these changes may indicate that the level or intensity of gene expression in SIBs is inadequate to bring about manifestations of the disorder; however, a minority of commonly dysregulated transcripts had this signature. Instead, most of the 82 transcripts were either up- or down-regulated in SIBs in both comparisons (with SZs and with CCSs). These changes in particular may indicate the presence of protective factors operating only within those who also have a genetic susceptibility to the disorder; i.e., only in SIBs and not in CCSs.

The results must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, this initial demonstrative study utilized a small sample. This small sample size imposed limits on inferential power and thus inhibited our ability to observe results for individual biomarkers that would withstand rigorous corrections for multiple testing (e.g., Bonferroni correction); nevertheless, we anticipate our findings will have substantial utility in highlighting candidate biomarkers and their associated effect sizes which can be exploited in the design of future studies designed prospectively to test these hypotheses with suitable levels of power. Second, despite our attempts to match the three subject groups on relevant demographics, a gender disparity was encountered which conceivably might alter the results. We statistically accounted for sex as a covariate in our analyses, but lacked inferential power to model sex-by-diagnosis interactions that might be operating. Thus, future work should focus on larger samples that are identical or nearly so with regard to sex and other relevant factors, such as ancestry, that have the potential to confound such analyses. Third, the results here were all derived by microarray which, while highly efficient, is not the most sensitive assay for measuring gene expression intensities. Although we lacked the ability in this small pilot study to verify microarray-derived results by a more sensitive method, such as quantitative real-time PCR, this is obviously a prerequisite for advancing any of the specific candidate biomarkers identified here to subsequent stages of experimentation, such as replication efforts in other samples, genetic association studies, or functional investigations into the biology of these genes. Nevertheless, our prior work and that of others has shown that a good proportion of microarray-derived results are ultimately verifiable by other methods; this, coupled with the fairly large numbers of candidate biomarkers identified in the various group comparisons, suggests that some true-positive results are likely contained within this set of putative biomarkers. Lastly, we would highlight that one strength of our study (our cell-isolation method) can not entirely overcome some of the weaknesses associated with examining peripheral blood as a source of biomarkers. Thus, while the technique we have used to isolate PBMCs produces a sample of cells for biomarker identification that is far more homogeneous than that obtained through whole-blood RNA extraction (a commonly used approach), PBMCs are themselves a functionally heterogeneous class of blood cells. For example, if different types of PBMCs (e.g., lymphocytes and macrophages) express different transcriptome signatures, and if our subject groups systematically differed in the proportion of different PBMC cell types in their blood samples, then some observed group differences in gene expression may actually reflect diagnostic-group differences in blood constitution rather than true group differences in gene expression within the same cells.