Abstract

Previous studies have established the existence of CD4-independent simian immunodeficiency virus, human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2), and laboratory strains of HIV-1. However, whether CD4-independent viruses may also exist in HIV-1-infected patients has remained unclear. We have recently reported the isolation of viruses from an AIDS patient that were able to infect CD8+ cells independent of CD4, using CD8 as a receptor. Using a similar approach, here we examined viruses from 12 randomly selected patients (obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Program, National Institutes of Health) for the presence of CD4-independent HIV-1. CD4-independent variants were isolated from infected CD8+ cells from the viral quasispecies of 7 of 12 patients. The CD4-independent isolates were able to infect primary CD8+ cells as well as a CD4− CD8+ T-cell line. Soluble CD4 and blocking anti-CD4 or -CD8 antibody had no effect on infection of CD8+ cells. Remarkably, two of the seven CD4-independent isolates, but not their parental bulk viruses, induced syncytia and caused acute death of infected CD8+ cells. Some of the CD4-independent variants were also able to infect U87 cells that were negative for CD4, CD8, and common HIV coreceptors, suggesting a novel entry mechanism for these isolates. The CD4-independent isolates were derived from adults and children infected with subtypes A, B, and D. Although no common motif for CD4 independence was found, novel sequence changes were observed in critical areas of the envelopes of the CD4-independent viruses. These results demonstrate that HIV-1-infected patients can frequently harbor viruses that are able to mediate CD4-independent infection of CD8+ cells. In addition, this study also provides evidence of primary HIV-1 variants that are syncytium inducing and acutely cytopathic for CD8+ lymphocytes.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) primarily infects CD4+ T cells and monocytes/macrophages, using CD4 as a receptor and CCR5 (R5) or CXCR4 (X4) as a coreceptor. However, previous studies have shown that simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) (6), HIV-2 (8, 29), and some laboratory strains of HIV-1 (5, 19, 21) can also infect cells independent of CD4. Studies have also shown that a wide range of CD4-negative cells, including fibroblasts (36), epithelial cells (27), and neural cells (13), can be infected in vitro by certain strains of HIV. Further, it is well established that in vivo HIV can enter a wide range of cells that do not express CD4, including the cells of the nervous (12) and renal (9, 28) systems. However, the significance of CD4-independent infection in AIDS pathogenesis has remained largely unknown because primary CD4-independent HIV-1 variants are rarely isolated from infected patients.

In contrast to CD4+ cells, CD8+ lymphocytes are usually resistant to HIV-1 infection, and these cells play an important protective role in AIDS pathogenesis. It is generally believed that HIV-1 disease progresses with the eventual failure of CD8+ cells that primarily control the primary virus infection for an extended period of time (9, 24) However, the exact reason why the immune CD8+ cells eventually fail in HIV-1 infection has remained unclear. Although several studies have previously reported that HIV-1 can be found in CD8+ cells both in vivo (22, 33) and in vitro (10, 17), it was assumed that infection of CD8+ cells probably occurred through transient expression of CD4 in the single-CD8+ cells or at a stage when the CD8+ cells were at a double-positive (CD4+ CD8+) stage during T-cell development. We have recently isolated productively infected CD8+ cells from an AIDS patient and found that some of the CD8+-cell-produced viruses were able to infect CD8+ cells independent of CD4, using CD8 as a receptor (31, 32). These findings raise the important question of whether the CD4-independent variants capable of infecting CD8+ cells are aberrant viruses that are present only in rare patients or whether these viruses may be present in other HIV-1-infected individuals. The in vivo evolution of HIV-1 that can directly infect CD8+ cells and other CD4-negative cells independent of CD4 may have important implications for AIDS pathogenesis.

In HIV-1-infected subjects, a large number of related but divergent viral variants coexist as a quasispecies. When viral isolates are generated from patients' peripheral blood mononuclear cells by short-term coculturing with uninfected peripheral blood mononuclear cells or CD4+ T cells, a similar viral quasispecies is likely to emerge. We hypothesized that even if CD4-independent viruses existed in the quasispecies of an infected individual, these variants were likely to be at a low abundance relative to the more common CD4-tropic strains. Therefore, in order to propagate the CD4-independent viruses, it might be necessary to enrich these variants from the bulk viral quasispecies.

In this study, we sought to investigate whether CD4-independent viruses exist in HIV-1-infected subjects. We found that CD4-independent variants could be isolated from 7 of 12 patients through infection of purified CD8+ T cells. The isolated CD4-independent variants were able to infect CD4− CD8+ cells independent of CD4. The CD4-independent isolates from two patients produced syncytia and caused acute death of the infected CD8+ cells. Although no common motif for CD4 independence was found, interesting changes were observed in the envelopes of the CD4-independent viruses from different patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of CD4-independent HIV-1.

We randomly selected 12 patients (obtained through the AIDS Research and Reagent Program [ARRP] at the National Institutes of Health [NIH]) infected with different subtypes of HIV-1 for isolation of CD4-independent HIV-1 variants. As listed by the ARRP, the 12 primary viruses that we tested were originally obtained from patients in North America, Africa, and Asia and contained R5-, X4-, or dual (R5X4)-tropic isolates of clades A, B, D, and E (Table 1). Some of these patients have been studied extensively by different groups over the years (3, 4, 7, 11, 23, 24, 37). Infection and isolation of CD4-independent viruses were performed by using a previously described technique (31). Briefly, purified CD4+ and CD8+ cells from healthy donors were infected simultaneously with the original bulk viral quasispecies from each patient (0.1 pg of p24/cell), and virus replication was monitored (31, 32). We used a rigorous approach to isolate CD4-independent strains from the bulk viral quasispecies of each of these patients. After infection of purified CD8+ cells, the cells were further sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) 3 to 4 days later, with a very conservative gate to exclude any contaminant CD4+ or double (CD4+ CD8+)-positive cells. Sorted CD8+ cells were tested for CD4 contamination by detection of CD4 mRNA by sensitive reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR. Infection of CD8+ cells was also monitored by detection of HIV DNA and mRNA by PCR and RT-PCR, respectively (31, 32). Only rarely was any mRNA for CD4 detected in the sorted CD8+ cells, and whenever any trace of CD4 mRNA was detected, cells were discarded from further experiments to avoid any possibility of contamination with CD4-tropic strains. It was previously reported that normal CD4-tropic HIV-1 strains are not able to enter such stringently selected CD8+ cells (31). Finally, the CD4-independent variants were grown from infected and sorted CD8+ cells in short-term (2 to 4 weeks) cocultures with (CD4-depleted) CD8+ cells from healthy donors.

TABLE 1.

Viruses obtained from the ARRP (NIH) for isolation of CD4-independent HIV-1

| Patient no. | Clade | Country | Sex/agec | Disease | Coreceptora | HIV DNA in CD8+ cellsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 92UG046 | D | Uganda | M/25 | Asymptomatic | X4 | + |

| 93UG086 | D | Uganda | U | U | R5X4 | + |

| 92US077 | B | United States | Infant | U | R5X4 | + |

| 93US143 | B | United States | Infant | U | R5X4 | + |

| 96USHIPS4 | B | United States | F/teenage | AIDS | R5X4 | + |

| 96USHIPS9 | B | United States | U | AIDS | R5X4 | + |

| 96USSN20 | A | United States and Senegal | M | AIDS | R2B, -3, -4, -5, X4 | + |

| 92UG001 | D | Uganda | M/26 | Asymptomatic | R5X4 | − |

| 92US727 | B | United States | U | U | R5 | − |

| 91US056 | B | United States | Infant | U | R5 | − |

| 93US151 | B | United States | Infant | U | R5X4 | − |

| CMU08 | E | Thailand | U | U | X4 | − |

As listed in ARRP, NIH.

Tested in infected and sorted CD8+ cells as described in Materials and Methods. +, present; −, not present.

U, unknown.

HTAs.

For determination of whether the CD4-independent viruses from different patients were preexistent in the viral isolates from the ARRP and for examination of the relative abundance of the CD4-independent variants, heteroduplex tracking assays (HTA) were performed as previously described (18, 25). Briefly, viral RNA was isolated from culture supernatants and used in RT-PCR to generate 400-bp V1/V2 or 144-bp V3 products. The same regions were also amplified from cloned env genes by PCR. Two probes were end labeled for analysis of each region (BaL and JR-FL sequences for V1/V2 and JR-FL and a clade C sequence for V3). Products were mixed individually with the appropriate probes, heated to denature the duplexes, and cooled to allow heteroduplexes to form. The heteroduplexes were separated on 6% (V1/V2) or 12% (V3) nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels and visualized by autoradiography and phosphorimaging (Molecular Dynamics). The relative abundance of each variant in the isolates was determined by ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics) analysis by summing the intensities for all heteroduplex bands within a lane and dividing the intensity for each band by the sum. Duplicate RT-PCR products were analyzed, and the relative abundances for each band were averaged. Some products were cloned into the pT7Blue-3 vector by use of the Perfectly Blunt cloning kit (Novagen). Clones were screened by HTA and sequenced as described previously (25).

CD4-independent infection of CD8+ cells.

The CD4-independent viruses were tested for the ability to infect primary CD8+ cells as well as KRCD8 cells, an established CD8+-T-cell line (31). A known CD4-tropic strain (IIIB) and primary HIV-1 that replicated only in CD4+ cells were used as negative controls for these experiments, while a previously isolated CD8-tropic strain (AD3.v6) was used as a positive control (31). All isolates were simultaneously tested for CD4 tropism by infection of primary CD4+ cells and a CD4+-T-cell line (MT-2). Infection and virus replication were closely monitored by PCR with genomic DNA from infected cells, by RT-PCR with infected cell lysates, by RT assays, and by p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with viral supernatants (31, 32). Because of the possibility of low levels of virus replication, virus production was also tested by the measurement of viral loads (RNA copy numbers) by use of an ultrasensitive AMPLICOR kit (Roche) with a detection limit of 50 copies of HIV-1 RNA per ml, according to the manufacturer's instructions. All viral isolates were further tested for infectivity in a biological assay with MT-2 cells by determination of the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) by conventional methods. Phenotypes of the infected cells were routinely checked by FACS analyses, using antibodies against different cell surface markers, including CD4 and CD8 (30). Although KRCD8 cells are known to be negative for CD4 expression, during infection of these cells, induction of CD4 mRNA was strictly monitored by FACS as well as RT-PCR. For further testing of the role of CD4 and CD8 molecules, CD8+ cells were infected in the presence of blocking anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and isotype control antibodies, as previously described (31). Infection of CD8+ cells was also performed with CD4-independent viruses or known CD4-tropic IIIB viruses that were pretreated for 1 h with soluble CD4 (sCD4-183 from the ARRP) at 10 μg/ml, and virus replication was monitored (31).

Use of coreceptors and syncytium induction.

The use of coreceptors by different CD4-independent isolates was tested by infection of a panel of U87 cells expressing CD4 and coreceptor CCR-1, -2, -3, -4, or -5 or CXCR4 (obtained through ARRP). The ability of the CD4-independent variants to induce syncytia was also tested in CD4+ X4+ MT-2 and CD4− X4− KRCD8 cells (31). As negative controls for these experiments, heat-inactivated (58°C for 1 h) viral stocks were used for infection.

Sequence analyses.

The full-length envelope (env) coding regions of the CD4-independent isolates were amplified from infected CD8+ cells by nested PCR, and the products were sequenced (31). The envelopes of the CD4-tropic viruses present in these patients were also sequenced for comparison with those from CD4+ cells infected with the bulk viral quasispecies from each patient. Whenever necessary, the envelopes of CD4-independent isolates were cloned and sequenced for comparison. The sequences were analyzed by a comprehensive VESPA analysis (20). The CD4-tropic env sequences from some of these patients are also available in the HIV sequence database and from previous studies (3, 4, 7, 11, 23, 24, 37).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of the CD4-independent variants isolated in this study have been submitted to GenBank (accession numbers AF 391548 to AF 391553 and AF 418562).

RESULTS

Evidence of CD4-independent HIV-1.

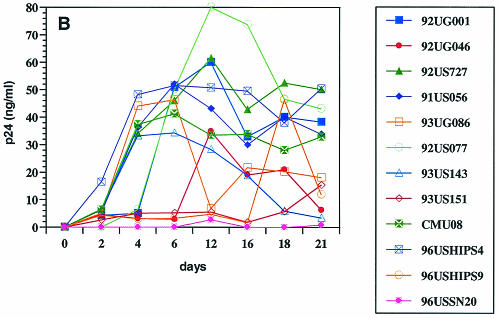

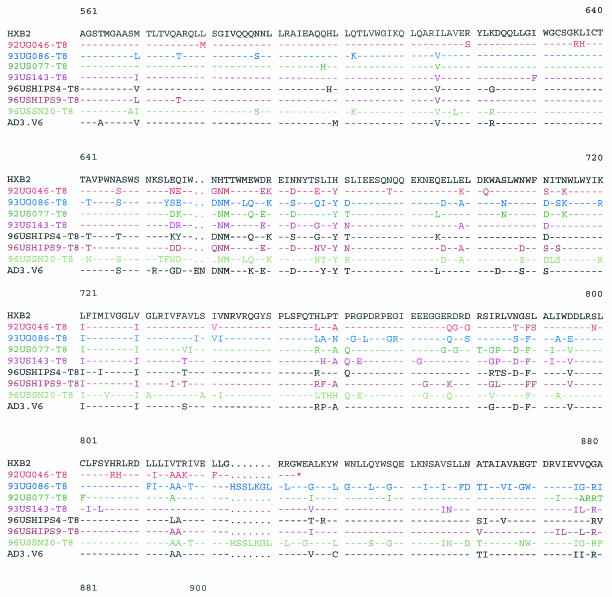

When purified CD8+ T cells were infected with the bulk viruses from different patients, low levels of virus replication were detected in 7 of 12 isolates examined (Fig. 1A). As expected, viruses from all patients replicated in CD4+ T cells, albeit at different levels (Fig. 1B). For most of the viruses that were able to replicate in CD8+ cells, virus production was significantly higher in CD4+ cells than in CD8+ cells. These infections were performed in parallel, using CD4+ and CD8+ target cells from the same donor to eliminate differential replicative capacities of HIV-1 in cells from different individuals. Some of the isolates (e.g., 92US727) failed to replicate in CD8+ cells but replicated to high levels in CD4+ cells, while other isolates (e.g., 96USSN20) replicated at low levels both in CD8+ and CD4+ cells. These results suggested that it is unlikely that the replication of the six isolates in purified CD8+ cells was due to the presence of a small (<1%) number of contaminating CD4+ cells. Furthermore, as previously reported (31), a well-studied CD4-tropic HIV-1 strain (IIIB) also failed to replicate in purified CD8+ cells (data not shown). These data indicated that CD4-independent HIV-1 variants appeared to be present in 6 of the 12 patients examined in this study.

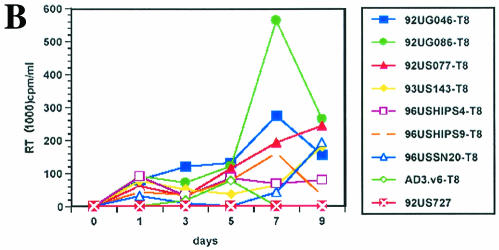

FIG. 1.

Infection and virus production in purified CD8+ (A) and CD4+ (B) cells by viruses from 12 patients (Table 1), as described in Materials and Methods. (C) RT-PCR detection of mRNA for CD8 (lanes 2 to 5), CD4 (lanes 6 to 9), and HIV-1 (lanes 10 to 13) from sorted CD8+ cells 3 days after infection with bulk viruses from a representative patient (96USHIPS4) from which a CD4-independent variant was isolated (lanes 2, 5, and 10) and from a patient (93US151) who did not harbor CD4-independent viruses (lanes 4, 7, and 12). Sorted CD8+ cells infected with previously identified CD4-independent CD8-tropic isolate AD3.v6 (31) (lanes 3, 6, and 11) and chronically infected CD4+ cell line 8E51 (lanes 5, 9, and 13) were used as controls. Lane 14, water control for PCR contamination. Parallel samples were run without reverse transcription as a control for DNA contamination of the samples (data not shown). The limit of detection of mRNA for CD4+ cells is 1 CD4+ cell in 100,000 cells (31) (data not shown).

After infection of CD8+ cells, the cells were rigorously sort-purified to exclude the possibility of CD4-tropic virus contamination. A sensitive RT-PCR that could detect the presence of a single CD4+ cell in 100,000 cells (31) (data not shown) did not detect any CD4 mRNA in the sorted CD8+ cells from which the CD4-independent variants were eventually isolated. HIV-specific mRNA was detected in the CD8+ cells infected with viruses from some of these patients (Fig. 1C). It should be noted that at the time of sorting of purified CD8+ cells, little or no virus production was detected in most of the infected cultures, which also ruled out the possibility of virus-induced down-modulation of CD4 molecules in the infected CD8+ cells (Fig. 1B). When sorted CD8+ cells were tested for the presence of viral DNA (gag), HIV-1 was detected for 7 of 12 patients examined, indicating infection of CD8+ CD4− cells by viruses from these patients (Table 1). Six of these seven patients that were HIV DNA positive also produced viruses after infection of primary CD8+ cells (Fig. 1A). The reason that viruses from one patient (96USHIP9) failed to replicate in CD8+ cells, in spite of these cells being HIV DNA positive, is not clear. However, as discussed below and in Table 2, virus replication was also detected for this patient's viruses when the infected CD8+ cells were cocultured with CD4-depleted cells from a healthy donor. Together, these data provide evidence of CD4-independent viruses being present in 7 of 12 patients tested in this study.

TABLE 2.

In vitro culturing of CD4-independent viruses with CD4+ and CD8+ cellsa

| Virus | Results for virus cocultured with CD8+ cells

|

Results for virus cocultured with CD4+ cells

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT (cpm/ml) (1,000) | Viral loadb (copies/ml) (105) | TCID50/0.2 mlc | Syncytia | RT (cpm/ml) (1,000) | Viral load (copies/ml) (105) | Syncytia | TCID50/0.2 ml | |

| 92UG046-T8 | 27 | <50 | 108 | + | 45 | <50 | + | 106.9 |

| 93UG086-T8 | 454 | 52.1 | >107 | − | 2,420 | 176.8 | + | >107 |

| 92US077-T8 | 632 | >37,500 | 106.85 | − | 246 | 946.6 | + | 107 |

| 93US143-T8 | 551 | 7,229.25 | 108.3 | + | 678 | 29,250 | + | >107 |

| 96USHIPS4-T8 | 1,780 | 2,604 | 107 | − | 3,097 | 1,298 | + | >107 |

| 96USHIPS9-T8 | 72 | <50 | 106.5 | − | 624 | 5092.2 | + | 107 |

| 96USSN20-T8 | 2,722 | 5.3 | 106.5 | − | 2,466 | 6.4 | + | >107 |

| AD3.v6 | 3,914 | 4,870.3 | 105.75 | − | NDd | 1,764.5 | + | NDd |

HIV-1 DNA-positive sorted CD8+ cells were cocultured with equal numbers of CD8+ or CD4+ cells from healthy donors, and virus production was detected at regular intervals. Data for peak virus production (between 7 and 14 days) are shown here.

Viral load was detected by using as AMPLICOR kit.

TCID50 was measured with MT-2 cells.

ND, not done.

Isolation of CD4-independent viruses.

In order to grow CD4-independent isolates, we cocultured infected and sorted CD8+ cells with purified CD8+ (CD4-depleted) T cells from healthy donors. No virus production was observed when CD8+ cells infected with any of the five isolates that failed to replicate in CD8+ cells were cocultured with either CD8+ or CD4+ cells from healthy donors. Indeed, these cocultures continuously remained HIV negative by PCR as the cocultures were monitored for up to 4 weeks, further affirming that no contaminating CD4-tropic viruses were present in the sorted CD8+ cells (data not shown). In contrast, virus production was readily detected when sorted CD8+ cells from the seven patients that were HIV-1 DNA positive were cocultured either with CD4+ (data not shown) or CD8+ (Table 2) cells. To distinguish them from the parental viruses, we named the CD4-independent strains isolated from cocultures with CD8+ cells with the suffix “T8” (as it originated from CD8+ cells) after the respective viral strain name. For example, 92US077-T8 is the CD4-independent variant that was isolated from patient 92US077. As mentioned above, all of the CD4-independent variants also replicated efficiently in CD4+ cells, suggesting that although they are CD4 independent, these viruses have maintained an unchanged ability to grow in CD4+ cells and thus should be considered dual (CD4/CD8)-tropic.

A wide range of virus production was detected in the CD8+ cell cocultures with viruses from different patients (Table 2). Several interesting observations were made when CD4-independent variants from different patients were grown in cocultures with CD4+ or CD8+ cells (Table 2). For example, in spite of containing high levels of infectious particles (TCID50s), viruses could not be detected in CD8+ even by the sensitive AMPLICOR assay with the CD4-independent isolates from two patients (Table 2). It has been reported that up to 7% of HIV-infected patients may remain undetectable by AMPLICOR (34). Interestingly, the original isolates from these two patients readily tested positive by AMPLICOR, suggesting that the CD4-independent isolates from these patients could be genotypically different variants present in the viral quasispecies (data not shown). In agreement with the X4 or R5 X4 phenotype of these isolates as listed by the ARRP (Table 1), all CD4-independent variants, as well as their parental bulk viruses, induced syncytia in primary CD4+ cells as well as in MT-2 cells (data not shown). Remarkably, CD4-independent variants from two patients (92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8) also induced syncytia in CD8+ cells (Table 2). The number and time course for the appearance of syncytia in CD8+ cells were comparable to those for CD4+ cells, suggesting that the formation of syncytia in CD8+ cells by these two variants was not due to the presence of contaminating CD4+ cells. Syncytium induction in CD8+ cells by the 92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8 strains was quickly followed by the acute death of the infected cells, providing evidence for the first time of syncytium-inducing (SI) and acutely cytopathic HIV-1 strains for CD8+ lymphocytes. Note that infection with the original isolates from none of these patients produced syncytia or caused cytopathic effects in CD8+ cells, suggesting that the isolated CD4-independent viruses from these two patients remained phenotypically distinguished minority variants that were present in the bulk viral quasispecies (data not shown).

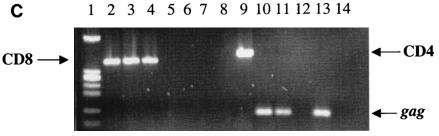

To further affirm that the CD4-independent viruses that were isolated from the seven patients were present in the original viral isolates and did not emerge during in vitro virus propagation, we performed V1/V2- and V3-specific HTA analyses to compare the variants present in the original isolates, the isolates propagated in CD4+ cells, and the isolated CD4-independent viruses for the two patients, 93US143 and 92UG046, from whom the CD4-independent isolates induced syncytia in CD8+ cells. V3-HTA analysis indicated that single V3 genotypes existed in both original isolates that were consistent with all of the downstream isolates (data not shown). However, V1/V2-HTA showed multiple genotypic variants in both original isolates. Isolate 93US143 had three different variants that were maintained during CD4+ cell propagation, and one of these genotypic sequences corresponds with the env clone derived from the CD4-independent isolate from the CD8+ cell propagation of this strain (Fig. 2). An early passage of the CD4-independent isolate 93US143-T8 was unavailable for analysis, and analysis of a later passage of the isolate indicated that all of the variants had acquired the new mutations (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with isolate 92UG046, in that two genotypic variants were seen in the original isolate and the isolate propagated in CD4+ cells, and the env clone generated from 92UG046-T8 matched the V1/V2 migration of one of the two heteroduplex bands of the original isolate (data not shown). The 93US143-T8 clone sequence represented 22% of the 93US143 isolate and the 92UG046-T8 clone sequence represented 55% of the 92UG046 isolate. It should be noted that the relative abundance of the clone sequences was determined only for the V1/V2 region and that the variants in the isolates with these V1/V2 sequences are likely to have differences outside of V1/V2 that influence their ability to replicate in CD4-negative cells; thus, the actual frequency of the CD4-independent variants present in the quasispecies is likely to be <22 to 55%. Nevertheless, these data indicate that the CD4-independent variants that we have isolated from infected CD8+ cells were present in vivo in the patients' bulk viral quasispecies. Taken together, these results demonstrate that 7 of 12 patients examined in this study harbored CD4-independent HIV-1 viral variants in the viral quasispecies that were able to infect CD8+ cells in the absence of CD4. These data also show that CD4-independent variants from two patients were SI and acutely cytopathic for primary CD8+ cells.

FIG. 2.

HTA of the V1/V2 loop of the original viral quasispecies, viruses grown in vitro in CD4+ cells, and the cloned envelope of the CD4-independent variant from patient 93US143. Lanes 1 and 2, the original isolate and the isolate grown in CD4+ cells, respectively; lane 3, the cloned envelope from the CD4-independent variant isolated from the patient. The bands were sequenced for confirmation of the fragments as described in Materials and Methods (data not shown).

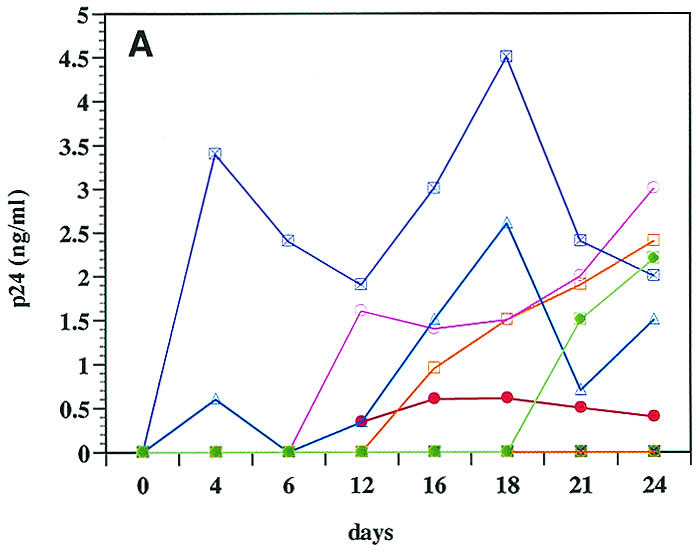

CD4-independent infection of CD8+ cells.

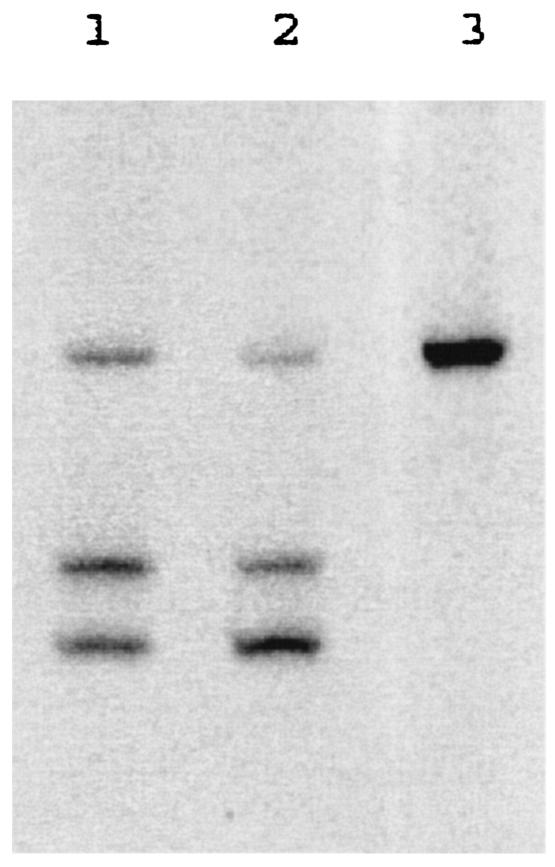

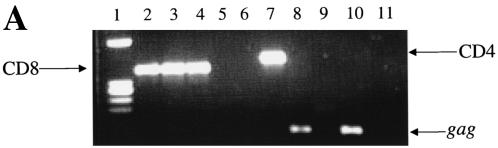

To further characterize the CD4-independent phenotype of these viruses, we examined the ability of different CD4-independent variants to infect a CD8+-T-cell line (KRCD8) that does not express CD4 and has been shown to be resistant to regular CD4-tropic HIV-1 (31). As shown for a representative experiment in Fig. 3A, HIV-specific transcripts (gag) were evident in KRCD8 cells after infection with CD4-independent variant 96USSN20-T8 (lane 8), but not with CD4-tropic isolate 93US151 (lane 9). KRCD8 cells expressed CD8 mRNA, but no CD4 mRNA was detected in these cells, indicating that virus entry into these cells was independent of CD4 (Fig. 3A). All of the CD4-independent variants, as well as a previously identified CD8-tropic strain, AD3.v6, replicated in KRCD8 cells, while viruses from none of the patients that contained only CD4-tropic strains were able to replicate in these cells (Fig. 3B). It is noteworthy that the original isolates from patients that harbored CD4-independent variants also failed to replicate in KRCD8 cells (data not shown), further suggesting that the CD4-independent viruses were minority variants present in the viral quasispecies in these patients and had to be amplified during culture in order to isolate the CD4-independent strains. Although most of the CD4-independent variants induced low-grade infections in KRCD8 cells without any noticeable cytopathic effects, striking syncytia were produced after infection of KRCD8 cells with the 92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8 isolates (Fig. 3D). Productive infection was necessary for the induction of syncytia in KRCD8 cells, since no syncytia were visible after heat inactivation of the viruses (Fig. 3C). It may be noted that these two isolates also had induced syncytia in primary CD8+ T cells (Table 2). Like the case for primary CD8+ cells, acute death of KRCD8 cells occurred after infection with the 92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8 strains. These results establish that the 92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8 viruses are of the SI phenotype and are acutely cytopathic for CD8+ cells.

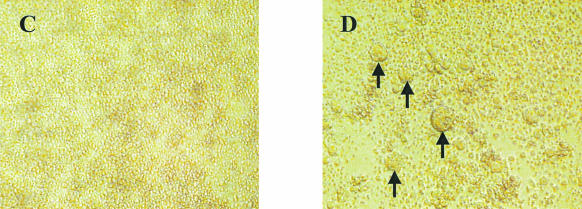

FIG. 3.

Effects of infection of KRCD8 cells with CD4-independent isolates. (A) Evidence of CD8, CD4, and HIV-1 mRNA after infection of KRCD8 cells with representative CD4-independent (96USSN20-T8) and control CD4-tropic (93US151) isolates. RT-PCR was performed for mRNA detection of CD8 (lanes 2 to 4), CD4 (lanes 5 to 7), and HIV-1 (lanes 8 to 10) by using specific primers (18). Lanes 2, 5, and 8, infection with 96USSN20-T8; lanes 3, 6, and 9, infection with 93US151; lanes 4, 7, and 10, respective positive controls; lane 11, water control for PCR contamination. All samples were run with and without RT to rule out DNA contamination (data not shown). (B) Infection and replication of CD4-independent isolates in KRCD8 cells. A representative CD4-tropic isolate (92US727) and previously identified CD8-tropic isolate AD3.v6 (18) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. (C and D) Induction of syncytia in KRCD8 cells. Syncytia were examined 3 days after infection of KRCD8 cells with a representative live (D) or heat-inactivated (C) CD4-independent virus, 92UG046-T8. Arrows point to some of the syncytia.

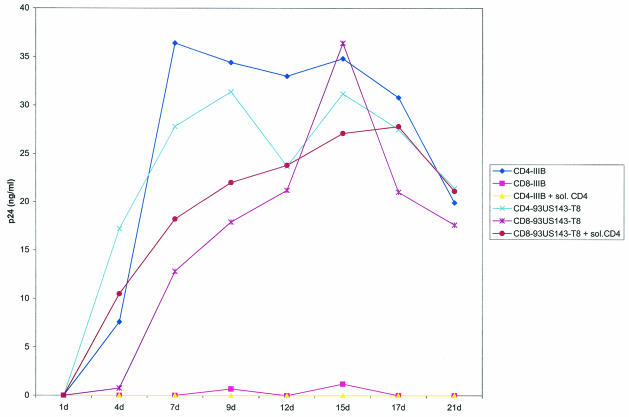

Replication of the CD4-independent isolates was also compared between CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Figure 4 shows replication of a CD4-independent strain (93US143-T8) in primary CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. The CD4-independent isolate replicated to comparable levels in purified CD8+ cells and CD4+ cells from the same donor, indicating that this variant has maintained CD8 as well as CD4 tropism. Furthermore, soluble CD4, as well as anti-CD4 antibodies (data not shown), had no effect on the infection of CD8+ cells by the 93US143-T8 isolate. In contrast, the CD4-tropic IIIB viruses replicated to a high level in CD4+ cells, and infection was blocked by pretreatment of these viruses with soluble CD4. As expected, IIIB viruses failed to replicate in CD4-depleted CD8+ cells, indicating the absolute requirement of CD4+ cells for the growth of these viruses (Fig. 4). It may be pertinent to mention here that although the original viral isolates from patient 93US143 were also able to infect CD8+ cells (Fig. 1A), replication of the CD4-independent variant isolated from the same quasispecies replicated far more efficiently in CD8+ cells. For example, the bulk viruses from patient 93US143 produced peak p24 levels of 34.3 and 2.6 ng/ml in CD4+ and CD8+ cells, respectively, indicating more robust virus replication in CD4+ cells than in CD8+ cells (Fig. 1A and B). In contrast, the CD4-independent isolate from the same patient (93US143-T8) produced peak p24 levels of 31.7 and 36.4 ng/ml in CD4+ and CD8+ cells, respectively, suggesting comparable replication efficiencies of these variants in CD4+ and CD8+ cells (Fig. 4). These experiments were repeated four times with comparable results. These results are consistent with our hypothesis that the CD4-independent viral variants were present in the original viral quasispecies and were amplified during CD8+ CD4− cell infection due to their enhanced ability to infect and replicate in CD8+ cells.

FIG. 4.

Infection of primary CD4+ and CD8+ cells by CD4-independent isolate 93US143-T8 and CD4-tropic HIV-1 strain IIIB. Infection of purified cells was performed with or without pretreatment of the viruses with soluble CD4 (sol. CD4) as described in Materials and Methods, and the infection was monitored by regular measurement of p24 antigen by ELISA. CD4-tropic IIIB viruses were used as a control in this experiment.

Viral entry and use of receptors or coreceptors.

Along with the CD4 receptor, most HIV-1 strains also require R5 or X4 as a coreceptor for viral entry. Accordingly, HIV-1 isolates have been classified into phenotype SI X4 or non-SI (NSI) R5 based on the ability to use the CXCR4 or CCR5 coreceptor, respectively. Most of the SI strains are also able to induce syncytia in CD4+ cells such as MT-2 cells (2). Previously identified CD4-independent isolates from our laboratory were NSI in CD8+ cells even though these viruses were X4 and SI in primary CD4+ cells as well as MT-2 cells (31). Each of the seven original isolates from which the CD4-independent variants were isolated for this study was classified by the ARRP as either X4 or R5X4 tropic, and none was just R5 tropic (Table 1). All CD4-independent variants isolated from these patients also maintained the SI X4 phenotype, as they were able to form syncytia in primary CD4+ cells as well as MT-2 cells (data not shown).

The coreceptor usage of the CD4-independent variants as well as their parental isolates was further characterized by infection of U87 cells that coexpressed CD4 and each of the commonly used HIV coreceptors (Table 3). Infection of the U87-CD4 cell lines was monitored by p24 ELISA and observation of syncytium formation. The use of coreceptors in U87-CD4 cells by the parental isolates generally matched the phenotypes listed by the ARRP (Tables 1 and 3). However, four of the CD4-independent isolates, but not their parental isolates, had an enhanced ability to use CCR1 as an additional coreceptor for infection of U87-CD4 cells. Syncytia were observed and p24 production was detected (except with one isolate) after infection of U87-CD4-CCR1 cells for four of the seven CD4-independent isolates (Table 3). Interestingly, one of the CD4-independent isolates (92UG046-T8) was able to infect all of the U87 cell types used in this study, including the parental U87 cells that did not express either CD4 or any of the coreceptors, suggesting that this variant was probably able to use an unidentified receptor for infection of the U87 cells. Note that the parental viruses from this patient (92UG046) were able to infect only the U87-CD4 cells that coexpressed either the R5 or X4 coreceptor (Table 3). These data suggest that the CD4-independent isolates were able to use a wider range of molecules as coreceptors for infection of CD4+ cells than were their parental isolates.

TABLE 3.

Use of coreceptors by the CD4-independent variants and their parental virusesa

| Virus | Infection of cells expressing the indicated receptorb

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U87 | U87-CD4 CCR1 | U87-CD4 CCR2 | U87-CD4 CCR3 | U87-CD4 CCR4 | U87-CD4 CCR5 | |

| 92-UG046-T8 | + (3) | + (3) | + (3) | + (4) | + (5) | + (7) |

| 92-UG046 | − | − | − | − | + (4) | + (5) |

| 93UG086-T8 | − | + (7) | − | − | + (7) | + (6) |

| 93UG086 | − | − | − | − | + (5) | + (5) |

| 92US077-T8 | − | + (6) | − | − | + (3) | + (6) |

| 92US077 | − | − | − | − | + (4) | + (5) |

| 93US143-T8 | − | − | − | − | + (3) | − |

| 93US143 | − | − | − | − | + (4) | − |

| 96USSHIPS-4T8 | − | − | − | − | + (3) | + (5) |

| 96USSHIPS4 | − | − | − | − | + (4) | + (5) |

| 96USSHIPS9-T8 | − | + (9) | − | − | + (4) | − |

| 96USSHIPS9 | − | − | − | − | + (4) | + (5) |

| 96USSN20-T8 | − | − | − | + (9) | + (4) | + (7) |

| 96USSN20 | − | − | − | − | + (4) | + (5) |

| LAI | − | − | − | − | + (7) | − |

| JR-FL | − | − | − | − | − | + |

U87 cells expressing different coreceptors were infected as described in Materials and Methods. Infections were scored by the presence of syncytia at different days postinfection and by an increase in p24 production (not shown).

+, infection; −, no infection. For cases when infection was present, the day postinfection when syncytia were detected is indicated in parentheses.

Previously isolated CD8-tropic viruses entered CD8+ cells independent of CD4 by using CD8 as a receptor, and antibodies against CD8 blocked infection of CD8+ cells (31). Anti-CD8 antibodies were unable to prevent infection of CD8+ cells by any of the CD4-independent viruses isolated for this study. In addition, soluble CD8 (a gift from George Gao, Oxford University, Oxford, England) also had no effect on infection of CD8+ cells by the CD4-independent viruses (data not shown). Some of the CD4-independent variants isolated in this study were also able to infect B cells that did not express either CD4 or CD8 (manuscript in preparation). Thus, although the exact mode of entry of the CD4-independent variants into the CD4-negative cells remains unclear at present, it appears that unlike the previously reported CD8-tropic strains (31), these variants do not use CD8 as a receptor for infection of CD8+ cells.

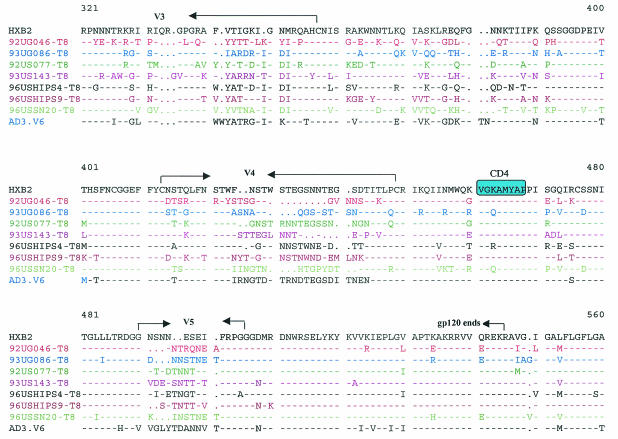

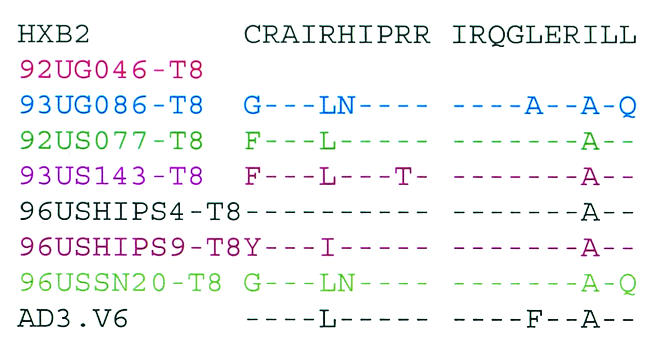

Envelope sequences of the CD4-independent isolates.

For infection with HIV-1, an interaction between the viral envelope (env) and cellular receptors or coreceptors is the first and most critical step (2). Changes in the viral env are likely to be responsible for the altered tropism of the CD4-independent variants. We sequenced the entire env genes of the CD4-independent viruses isolated from different patients. The env genes of the major CD4-tropic isolates present in these patients were also sequenced from bulk virus-infected CD4+ cells for comparison. Differences in the V1/V2, V3, V4/C4, and transmembrane (gp41) regions were observed between the CD4-independent variants and the original CD4-tropic isolates present in the same patient (data not shown). Although several changes were observed in the CD4-independent viruses from different patients, no obvious consensus sequence for CD4 independence was noticeable among the seven CD4-independent variants isolated in this study or the previously isolated CD8-tropic variant, AD3.v6 (Fig. 5). However, CD4-independent variants from several patients exhibited interesting sequence patterns. For example, although the CD4-tropic viruses from patient 92UG046 had a full-length env (data not shown), the CD4-independent variant isolated from this patient (92UG046-T8) had a sharply truncated cytoplasmic tail due to a point mutation in the transmembrane domain (Fig. 5). A truncated cytoplasmic tail has been associated with CD4-independent entry by a IIIB mutant (22). Another notable observation was the insertion of an HSSLKGLRL sequence in the gp41 region of two separate CD4-independent isolates, 96USSN20-T8 (subtype A) and 93UG086-T8 (subtype D) (Fig. 5). Although the HSSLKGLRL insertion has been found in subtype A, C, and G viruses, to our knowledge, this is the first subtype D virus to have this insertion.

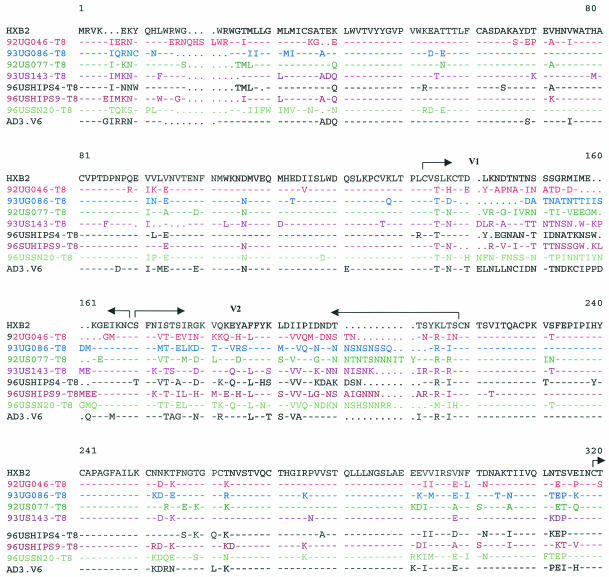

FIG. 5.

Comparison of the envelope sequences of the CD4-independent variants isolated from different patients and of the previously identified CD8-tropic virus AD3.v6 and CD4-tropic HIV-1 IIIB as controls (31). The premature ending of gp41 from one patient (92UG046-T8) is marked (*). Important areas have been highlighted.

The V3 loop has been identified as the major determinant of cellular tropism and coreceptor specificity for HIV-1 (15). Several unique features were noted in the V3 loop sequences of the two isolates, 92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8, that induced syncytia and were cytopathic for CD8+ cells (Fig. 5). N-linked glycosylation sites in env have been shown to play a critical role in HIV tropism and have been linked with CD4 independence for some strains (21, 26, 38). Nearly all R5X4 viruses maintain an asparagine (N) residue towards the amino terminus of the V3 loop, corresponding to position 324 in Fig. 5 (15). Although this asparagine residue remained unchanged in most of the CD4-independent strains, both 92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8 had substitutions for this asparagine residue, resulting in the loss of the critical N-linked glycosylation site. However, in spite of this loss of the N-linked glycosylation site, both of these SI variants maintained R5X4 tropism for CD4+ cells (Table 3). Further, the arginine (R) residue corresponding to position 331 (Fig. 5) makes a critical contribution to CXCR4 binding by HIV-1 (1), and a change of this basic residue to a neutral proline (P) residue has been correlated with CD4-independent infection (38). Interestingly, the arginine in position 331 has been replaced with proline in both the 92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8 variants, but not in any of the other CD4-independent strains (Fig. 5). Also, in the context of the GPGR residues at the apex of the V3 loop, a downstream IGXI motif corresponding to positions 349 to 352 (Fig. 5) is essential for interaction with R5 coreceptors (15). Even though most of the CD4-independent variants isolated for this study maintained the IGXI motif, the first isoleucine (I) residue was mutated in both the 92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8 strains (Fig. 5). Thus, it appears that the two SI isolates that were also cytopathic for CD8+ cells had interesting similarities in their V3 loop sequences. Further studies will be necessary to understand whether these changes in the V3 loop had any role in the unique phenotypes of these two variants. It is also important to remember that all of the CD4-independent variants isolated in this study maintained CD4 tropism, since each of these viruses continued to replicate efficiently in CD4+ cells. Therefore, although the sequences obtained from infected CD8+ cells are likely to be associated with CD4 independence, sequences from CD4+ cells may or may not be exclusive for CD4 tropism. Future studies with recombinant and mutant viruses will be necessary to identify the exact mutations responsible for the changed tropism of these CD4-independent viruses.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that CD4-independent viruses that can infect CD8+ lymphocytes frequently exist in HIV-1-infected patients. The CD4-independent isolates, however, still maintain the ability to infect CD4+ cells. Members of our laboratory previously isolated CD4-independent and CD8-tropic HIV-1 from an AIDS patient (31). Here we provide evidence of the presence of CD4-independent viruses in other AIDS patients as well as in HIV-1-positive asymptomatic individuals. We further provide evidence of the presence of CD4-independent HIV-1 variants that are able to induce syncytia and cause acute death of infected CD8+ cells. The CD4-independent viruses were isolated from patients who have been previously studied by different laboratories. The CD4-independent variants included viruses from the A, B, and D subtypes of HIV-1, indicating that the evolution of these novel HIV-1 strains is probably independent of viral genotype.

The CD4-independent viruses were isolated from infected CD8+ cells. It is unlikely that the infection of CD8+ cells with isolates from 7 of 12 randomly selected patients was due to CD4+ cell contamination for several reasons. First, CD8+ cells were purified, infected, and then sorted to eliminate any cells expressing CD4 molecules. Indeed, no CD4 expression was detected in these cells either by FACS (data not shown) or by sensitive RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). Thus, no CD4 cells had contaminated the CD8+ cell pools from which the CD4-independent variants were isolated. Second, CD8+ cells infected with viruses from the five patients that failed to replicate in CD8+ cells continuously remained PCR negative for HIV, even though these viruses replicated efficiently in CD4+ cells, suggesting that there was no CD4 contamination (Fig. 1B). Third, no viral DNA was detected in sort-purified CD8+ cells after infection with a highly virulent CD4-tropic (IIIB) HIV-1 strain (data not shown), indicating that our method of isolating CD4-independent viruses was unlikely to be contaminated with pure CD4-tropic viruses.

An interesting feature of this study was the observation of syncytia and acute death of CD8+ cells after infection with the CD4-independent variants from two patients (92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8) (Table 2 and Fig. 3C and D). Infection of CD8+ cells by previously identified CD4-independent isolates from a single patient was not cytopathic and did not produce syncytia (31). Most of the CD4-independent viruses isolated in this study also were not acutely cytopathic or SI in CD8+ cells. These findings suggest that the CD4-independent viruses may also be of the SI or NSI phenotype for CD8+ cells. Further, the two viruses that induced syncytia in CD8+ cells did not replicate at increased levels in CD8+ cells compared to the viruses that did not cause syncytia in these cells (Table 2 and Fig. 3B), suggesting that these two CD4-independent SI variants may be inherently more fusogenic in CD8+ cells. Similar inherently fusogenic SIV strains have been described previously (16). It is interesting that all of the CD4-independent viruses isolated in this study and the previously isolated CD4-independent variants (31) were able to form syncytia in primary CD4+ cells as well as in MT-2 cells, suggesting the ability of these isolates to use the X4 coreceptors that are usually responsible for syncytia in CD4+ T cells. However, only the 92UG046-T8 and 93US143-T8 variants were able to induce syncytia in CD8+ cells. Therefore, the CD4 SI phenotype does not predict a CD8 SI phenotype, and induction of syncytia in CD8+ cells may be independent of the X4 coreceptor. The molecule(s) responsible for the induction of syncytia in CD8+ cells remains unclear at present.

Previously isolated CD4-independent viruses were able to infect CD8+ lymphocytes by using CD8 as a receptor (31). Anti-CD8 antibodies were not able to prevent infection of CD8+ cells by any of the CD4-independent variants isolated in this study (data not shown). Further, the CD4-independent variants from one patient (92UG046-T8) were able to infect parental U87 cells that were negative for CD4, CD8, and all of the common HIV coreceptors, including R5 and X4 (Table 3). Indeed, the 92UG046-T8 isolate was also able to infect other CD4-negative cell lines, including HeLa and GHOST cells (data not shown), suggesting the possibility of a novel mode of viral entry for this variant. Also, primary B cells and B-cell lines (B-LCL) that expressed neither CD4 nor CD8 were susceptible to infection with some of the CD4-independent viruses isolated here (unpublished data). Therefore, although the exact mode of entry into CD8+ cells by the CD4-independent viruses remains unknown, it appears that these novel variants did not use CD8 molecules as a receptor for infection of CD8+ cells. Previously identified CD4-independent viruses were reported to have an enhanced ability to use either X4 or R5 molecules in the absence of CD4 to enter CD4-negative cells (2, 6, 8, 19, 21, 29). The CD4-independent isolate 93US143-T8 was able to enter quail cells independent of CD4 by using X4 molecules alone (Robert W. Doms, University of Pennsylvania, personal communication). However, antibodies against X4 or R5 were not able to prevent infection by the CD4-independent viruses isolated in this study (unpublished observation). Therefore, whether X4 and R5 coreceptors are involved in viral entry into the CD4-negative cells remains unclear at the present time. Nevertheless, infection of CD8+ lymphocytes in vivo through an X4 or R5 coreceptor in the absence of CD4 has not been reported. It is also possible that CD4-independent viruses from different patients may have adapted to use different routes to infect CD4-negative cells. Although no specific motifs for CD4 independence were apparent in the env sequences of different CD4-independent isolates, several interesting changes were noticeable in the important V1/V2, V3, V4/C4, and gp41 regions of different CD4-independent viruses. The previously identified CD4-independent variants that used CD8 as a receptor had a unique insertion of a long string of amino acids in the V1/V2 loop that none of the viruses isolated in this study shared (Fig. 5). The unique changes observed in different parts of env for the CD4-independent viruses are likely related to the novel phenotypes of these HIV-1 variants. Further studies are necessary to identify the specific changes in the envelope responsible for CD4 independence.

The in vivo evolution of HIV-1 variants that are adapted to use additional coreceptors under selective pressure is well established (14). All of the CD4-independent variants isolated in this study were from patients who were infected with either X4 or R5X4 viruses that usually appear late in HIV-1 disease. It is tempting to speculate that the CD4-independent variants may evolve with the progression of HIV-1 disease and under selection pressure from a decline in the number of primary target CD4+ cells. Future longitudinal studies with a larger cohort of patients will be necessary to establish this hypothesis. The CD4-independent viruses were isolated for this study from short-term cultures in vitro. We wondered about the possibility of the emergence of these novel HIV-1 strains during the in vitro propagation of these viruses. Comparison by HTA of the original viral quasispecies with the viruses isolated by traditional short-term culturing with primary CD4+ cells and of the cloned CD4-independent strains from the two patients indicated that the CD4-independent viruses that we isolated existed in the original viral quasispecies as a minority variant (Fig. 2). Sequence analysis of the V1/V2 regions confirmed that the CD4-independent clone sequence from 93US143-T8 was the same as that from one of the variants in the parental isolate (data not shown). The CD4-independent V1/V2 sequences were present at a frequency that was 22 to 55% of that of the parental isolates, but it is likely that a much smaller proportion of these isolates have the CD4-independent phenotype due to other possible sequence differences outside of the V1/V2 region. Also, investigators in the World Health Organization network for HIV isolation and characterization have extensively studied the V3 loop and the surrounding regions of the env gene from patient 92UG046. The sequences present in this primary viral isolate were compared to viral sequences derived from a homologous plasma sample (4) Although several differences were reported between the plasma and the primary viral isolate, the sequence of the cloned CD4-independent variant isolated from this patient for our study was identical to those of the primary viruses originally isolated from the patient (4). These results further establish that the CD4-independent viruses that we have isolated were indeed present in this patient in vivo.

The emergence of CD4-independent viruses in vivo may potentially have serious consequences for HIV disease pathogenesis. Although the exact mode of transmission of CD4-independent viruses remains unclear at present, two of the CD4-independent strains in this study were isolated from infants, suggesting that these novel strains can be transmitted perinatally (Table 1). Note that both infants from whom CD4-independent variants were isolated remained seronegative (35). The CD4-independent viruses appear to induce low and sometimes almost undetectable levels of infection in CD4-negative cells, making identification of these novel variants more difficult. Further, the unchanged ability of these variants to efficiently replicate in CD4+ cells makes recognition of these viruses even more challenging. Although HIV infection of CD8+ cells in vivo has been known of for a long time, the exact nature of the viruses that enter CD8+ cells has remained unclear (22, 33). There is little dispute that the effect of the evolution of CD4-independent HIV-1 strains in vivo could be far-reaching. Even though CD8+ cells were not acutely killed after infection with previously identified CD8-tropic viruses (31) or with most of the CD4-independent isolates in this study, it is possible that in vivo infection of CD8+ cells could affect the functional activities of these important immune cells. It is also possible that chronically infected CD8+ cells could be killed in vivo by other HIV-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, leading to a quantitative failure of these protective cells. More importantly, the evidence of CD4-independent variants from two patients with acute fusogenic and cytopathic effects on CD8+ cells clearly suggests that the emergence of such variants may lead to the rapid declines in CD8+ T cells in HIV-1-infected patients that are sometimes observed in the late stages of HIV-1 disease.

In summary, our results demonstrate that CD4-independent variants that can infect CD8+ cells may frequently be present in HIV-1-infected patients. Our results also show that some of the CD4-independent variants may induce syncytia and cause acute death of infected CD8+ cells. Although the exact mode of entry into CD4-negative cells remains unclear, it appears that some of the CD4-independent variants may use novel pathways for infection of CD4-negative cells. Identification of CD4-independent HIV-1 variants may be difficult due to unique phenotypic and genotypic changes in these variants. The emergence of CD4-independent variants in vivo may have important implications for AIDS pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization, the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, David Ho, Cecelia Hutto, Merlin Robb, John Sullivan, Kenrad Nelson, Dennis Ellenberger, Patrick Sullivan, and Renu Lal for providing the viral samples. We thank Christopher Walker of Children's Research Institute, Columbus, Ohio, for helpful discussions about this study. We also thank Gerald Learn and James Mullins of the University of Washington for help with the sequence analysis; Jianchao Zhang, Hui Yan, Amy Traven, Cindy McAllister of Children's Hospital, and Michael Klocke of the University of Cincinnati for technical assistance; and Amy Dutcher for her excellent help with preparing the manuscript.

This study was supported by NIH grants AI-42715 and AI-44974 and by a grant from the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amFAR) to K.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basmaciogullari, S., G. J. Babcock, D. Van Ryk, W. Wojtowicz, and J. Sodroski. 2002. Identification of conserved and variable structures in the human immunodeficiency virus gp120 glycoprotein of importance for CXCR4 binding. J. Virol. 76:10791-10800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger, E. A., P. M. Murphy, and J. M. Farber. 1999. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:657-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornelissen, M., G. Kampinga, F. Zorgdrager, J. Goudsmit, and the UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes defined by env show high frequency of recombinant gag genes. J. Virol. 70:8209-8212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Wolf, F., E. Hogervorst, J. Goudsmit, E. M. Fenyo, H. Rubsamen-Waigmann, H. Holmes, B. Galvao-Castro, E. Karita, C. Wasi, S. D. Sempala, et al. 1994. Syncytium-inducing and non-syncytium-inducing capacity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes other than B: phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. WHO Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:1387-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumonceaux, J., S. Nisole, C. Chanel, L. Quivet, A. Amara, F. Baleux, P. Briand, and U. Hazan. 1998. Spontaneous mutations in the env gene of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 NDK isolate are associated with a CD4-independent entry phenotype. J. Virol. 72:512-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edinger, A. L., J. L. Mankowski, B. J. Doranz, B. J. Margulies, B. Lee, J. Rucker, M. Sharron, T. L. Hoffman, J. F. Berson, M. C. Zink, V. M. Hirsch, J. E. Clements, and R. W. Doms. 1997. CD4-independent, CCR5-dependent infection of brain capillary endothelial cells by a neurovirulent simian immunodeficiency virus strain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14742-14747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellenberger, D. L., P. S. Sullivan, J. Dorn, C. Schable, T. J. Spira, T. M. Folks, and R. B. Lal. 1999. Viral and immunologic examination of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected, persistently seronegative persons. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1033-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Endres, M. J., P. R. Clapham, M. Marsh, M. Ahuja, J. D. Turner, A. McKnight, J. F. Thomas, B. Stoebenau-Haggarty, S. Choe, P. J. Vance, T. N. Wells, C. A. Power, S. S. Sutterwala, R. W. Doms, N. R. Landau, and J. A. Hoxie. 1996. CD4-independent infection by HIV-2 is mediated by fusin/CXCR4. Cell 87:745-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fauci, A. S. 1996. Host factors and the pathogenesis of HIV-induced disease. Nature 384:529-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flamand, L., R. W. Crowley, P. Lusso, S. Colombini-Hatch, D. M. Margolis, and R. C. Gallo. 1998. Activation of CD8+ T lymphocytes through the T cell receptor turns on CD4 gene expression: implications for HIV pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3111-3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao, F., D. L. Robertson, S. G. Morrison, H. Hui, S. Craig, J. Decker, P. N. Fultz, M. Girard, G. M. Shaw, B. H. Hahn, and P. M. Sharp. 1996. The heterosexual human immunodeficiency virus type 1 epidemic in Thailand is caused by an intersubtype (A/E) recombinant of African origin. J. Virol. 70:7013-7029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorry, P. R., G. Bristol, J. A. Zack, K. Ritola, R. Swanstrom, C. J. Birch, J. E. Bell, N. Bannert, K. Crawford, H. Wang, D. Schols, E. De Clercq, K. Kunstman, S. M. Wolinsky, and D. Gabuzda. 2001. Macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from brain and lymphoid tissues predicts neurotropism independent of coreceptor specificity. J. Virol. 75:10073-10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harouse, J. M., C. Kunsch, H. T. Hartle, M. A. Laughlin, J. A. Hoxie, B. Wigdahl, and F. Gonzalez-Scarano. 1989. CD4-independent infection of human neural cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 63:2527-2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman, T. L., E. B. Stephens, O. Narayan, and R. W. Doms. 1998. HIV type I envelope determinants for use of the CCR2b, CCR3, STRL33, and APJ coreceptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11360-11365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung, C. S., N. Vander Heyden, and L. Ratner. 1999. Analysis of the critical domain in the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 involved in CCR5 utilization. J. Virol. 73:8216-8226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson, G. B., M. Halloran, D. Schenten, J. Lee, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, J. Manola, R. Gelman, B. Etemad-Moghadam, E. Desjardins, R. Wyatt, N. P. Gerard, L. Marcon, D. Margolin, J. Fanton, M. K. Axthelm, N. L. Letvin, and J. Sodroski. 1998. The envelope glycoprotein ectodomains determine the efficiency of CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion in simian-human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Exp. Med. 188:1159-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitchen, S. G., Y. D. Korin, M. D. Roth, A. Landay, and J. A. Zack. 1998. Costimulation of naive CD8+ lymphocytes induces CD4 expression and allows human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 72:9054-9060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitrinos, K. M., N. G. Hoffman, J. A. Nelson, and R. Swanstrom. 2003. Turnover of env variable region 1 and 2 genotypes in subjects with late-stage human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 77:6811-6822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolchinsky, P., T. Mirzabekov, M. Farzan, E. Kiprilov, M. Cayabyab, L. J. Mooney, H. Choe, and J. Sodroski. 1999. Adaptation of a CCR5-using, primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate for CD4-independent replication. J. Virol. 73:8120-8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korber, B., and G. Myers. 1992. Signature pattern analysis: a method for assessing viral sequence relatedness. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 8:1549-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaBranche, C. C., T. L. Hoffman, J. Romano, B. S. Haggarty, T. G. Edwards, T. J. Matthews, R. W. Doms, and J. A. Hoxie. 1999. Determinants of CD4 independence for a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variant map outside regions required for coreceptor specificity. J. Virol. 73:10310-10319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livingstone, W. J., M. Moore, D. Innes, J. E. Bell, and P. Simmonds. 1996. Frequent infection of peripheral blood CD8-positive T-lymphocytes with HIV-1. Edinburgh Heterosexual Transmission Study Group. Lancet 348:649-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCutchan, F. E., K. Viputtigul, M. S. de Souza, J. K. Carr, L. E. Markowitz, P. Buapunth, J. G. McNeil, M. L. Robb, S. Nitayaphan, D. L. Birx, and A. E. Brown. 2000. Diversity of envelope glycoprotein from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 of recent seroconverters in Thailand. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:801-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMichael, A. J., and R. E. Phillips. 1997. Escape of human immunodeficiency virus from immune control. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:271-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson, J. A., F. Baribaud, T. Edwards, and R. Swanstrom. 2000. Patterns of changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V3 sequence populations late in infection. J. Virol. 74:8494-8501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogert, R. A., M. K. Lee, W. Ross, A. Buckler-White, M. A. Martin, and M. W. Cho. 2001. N-linked glycosylation sites adjacent to and within the V1/V2 and the V3 loops of dualtropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate DH12 gp120 affect coreceptor usage and cellular tropism. J. Virol. 75:5998-6006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pang, S., D. Yu, D. S. An, G. C. Baldwin, Y. Xie, B. Poon, Y. H. Chow, N. H. Park, and I. S. Chen. 2000. Human immunodeficiency virus Env-independent infection of human CD4− cells. J. Virol. 74:10994-11000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray, P. E., X. H. Liu, D. Henry, L. Dye III, L. Xu, J. M. Orenstein, and T. E. Schuztbank. 1998. Infection of human primary renal epithelial cells with HIV-1 from children with HIV-associated nephropathy. Kidney Int. 53:1217-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reeves, J. D., S. Hibbitts, G. Simmons, A. McKnight, J. M. Azevedo-Pereira, J. Moniz-Pereira, and P. R. Clapham. 1999. Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) isolates infect CD4-negative cells via CCR5 and CXCR4: comparison with HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus and relevance to cell tropism in vivo. J. Virol. 73:7795-7804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saha, K., R. Ware, M. J. Yellin, L. Chess, and I. Lowy. 1996. Herpesvirus saimiri-transformed human CD4+ T cells can provide polyclonal B cell help via the CD40 ligand as well as the TNF-alpha pathway and through release of lymphokines. J. Immunol. 157:3876-3885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saha, K., J. Zhang, A. Gupta, R. Dave, M. Yimen, and B. Zerhouni. 2001. Isolation of primary HIV-1 that target CD8+ T lymphocytes using CD8 as a receptor. Nat. Med. 7:65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saha, K., J. Zhang, and B. Zerhouni. 2001. Evidence of productively infected CD8+ T cells in patients with AIDS: implications for HIV-1 pathogenesis. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 26:199-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semenzato, G., C. Agostini, L. Ometto, R. Zambello, L. Trentin, L. Chieco-Bianchi, and A. De Rossi. 1995. CD8+ T lymphocytes in the lung of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients harbor human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Blood 85:2308-2314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Si-Mohamed, A., L. Andreoletti, I. Colombet, M. P. Carreno, G. Lopez, G. Chatelier, M. D. Kazatchkine, and L. Belec. 2001. Quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) RNA in cell-free cervicovaginal secretions: comparison of reverse transcription-PCR amplification (AMPLICOR HIV-A MONITOR 1.5) with enhanced-sensitivity branched-DNA assay (Quantiplex 3.0). J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2055-2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan, P. S., C. Schable, W. Koch, A. N. Do, T. Spira, A. Lansky, D. Ellenberger, R. B. Lal, C. Hyer, R. Davis, M. Marx, S. Paul, J. Kent, R. Armor, J. McFarland, J. Lafontaine, S. Mottice, S. A. Cassol, and N. Michael. 1999. Persistently negative HIV-1 antibody enzyme immunoassay screening results for patients with HIV-1 infection and AIDS: serologic, clinical, and virologic results. Seronegative AIDS Clinical Study Group. AIDS 13:89-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tateno, M., F. Gonzalez-Scarano, and J. A. Levy. 1989. Human immunodeficiency virus can infect CD4-negative human fibroblastoid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:4287-4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. 1994. HIV type 1 variation in World Health Organization-sponsored vaccine evaluation sites: genetic screening, sequence analysis, and preliminary biological characterization of selected viral strains. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:1327-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, P. F., P. Bouma, E. J. Park, J. B. Margolick, J. E. Robinson, S. Zolla-Pazner, M. N. Flora, and G. V. Quinnan, Jr. 2002. A variable region 3 (V3) mutation determines a global neutralization phenotype and CD4-independent infectivity of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope associated with a broadly cross-reactive, primary virus-neutralizing antibody response. J. Virol. 76:644-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]