Abstract

Previous studies identified in retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells an M-type K+ current, which in many other cell types is mediated by channels encoded by KCNQ genes. The aim of this study was to assess the expression of KCNQ genes in the monkey RPE and neural retina. Application of the specific KCNQ channel blocker XE991 eliminated the M-type current in freshly isolated monkey RPE cells, indicating that KCNQ subunits contribute to the underlying channels. RT-PCR analysis revealed the expression of KCNQ1, KCNQ4, and KCNQ5 transcripts in the RPE and all five KCNQ transcripts in the neural retina. At the protein level, KCNQ5 was detected in the RPE, whereas both KCNQ4 and KCNQ5 were found in neural retina. In situ hybridization in frozen monkey retinal sections revealed KCNQ5 gene expression in the ganglion cell layer and the inner and outer nuclear layers of the neural retina, but results in the RPE were inconclusive due to the presence of melanin. Immunohistochemistry revealed KCNQ5 in the inner and outer plexiform layers, in cone and rod photoreceptor inner segments, and near the basal membrane of the RPE. The data suggest that KCNQ5 channels contribute to the RPE basal membrane K+ conductance and, thus, likely play an important role in active K+ absorption. The distribution of KCNQ5 in neural retina suggests that these channels may function in the shaping of the photoresponses of cone and rod photoreceptors and the processing of visual information by retinal neurons.

Keywords: ion channels, patch clamp, M-type current, photoreceptors

patch-clamp studies on freshly isolated retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells from human (14, 47), monkey (47), and bovine retina (43) have demonstrated a sustained outwardly rectifying K+ current that is relatively insensitive to block by tetraethylammonium (TEA). This current activates at voltages positive to about −60 mV and, thus, contributes to the resting membrane potential. The kinetics and voltage dependence of this current (43) resemble those of the neuronal M-current, which was first described by Brown and colleagues as a neuronal K+ current in frog sympathetic ganglion cells that is suppressed by the stimulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (5, 7). In the past decade, it has been well established that many M-type currents are mediated by members of the KCNQ (Kv7) gene family (6, 38). The molecular correlates and function of the channel underlying the M-type current in RPE, however, remain unknown and need to be clarified.

The five members of the KCNQ gene family that have been identified to date encode six-transmembrane domain-spanning proteins. KCNQ/Kv7 channels are formed by the assembly of four identical KCNQ α-subunits or the coassembly of different KCNQ proteins (17, 38). The functional properties of KCNQ channels are altered by their coassembly with various smaller accessory β-subunits from the KCNE family, termed KCNE1–5 (38), and are modulated by multiple signaling pathways. For example, phosphorylation of KCNQ3, KCNQ4, and KCNQ5 by Src tyrosine kinase causes channel inhibition (11), and calmodulin confers Ca2+ sensitivity to KCNQ2, KCNQ4, and KCNQ5 channels (10).

Although KCNQ1 contributes to the K+ conductance in some epithelia (40), the expression of KCNQ2–5 is generally associated with excitable cells (38). Recent studies, however, have described the expression of members of the KCNQ family in a variety of other tissues, suggesting that these channels may have wider physiological roles than has been previously thought (33). Mutations in KCNQ1–4 underlie inherited cardiac arrhythmias (in some cases associated with deafness) (35, 46), neonatal epilepsy (41), and dominant progressive hearing loss (23). To date, KCNQ5 mutations are not known to be associated with human disease. KCNQ4 was cloned from a human retina cDNA library (23), and KCNQ4 splice variants have been detected in rat retina by PCR analysis (4). Little else is known about the expression and function of KCNQ channels in the retina.

To clarify the molecular basis of the M-type current in the RPE, we assessed the expression of KCNQ subunits in native monkey RPE. We found that, although KCNQ1, KCNQ4, and KCNQ5 transcripts are expressed in primate RPE, only KCNQ5 could be detected at the protein level. Transcripts for all five KCNQ subunits as well as KCNQ4 and KCNQ5 proteins were detected in neural retina. In addition, we detected KCNQ5 immunoreactivity near the RPE basal membrane as well as in rod and cone photoreceptor inner segments and elsewhere in the neural retina. The results suggest that KCNQ5 subunits contribute to M-type channels in the RPE basolateral membrane, where they likely participate in the transport of K+ from the retina to the choroid. KCNQ5 subunits may also contribute to voltage-gated K+ channels in the inner segments of rod and cone photoreceptors and in retinal neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Monkey RPE and Neural Retina

Monkey tissues were prepared as described previously (52). All animal procedures were in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) “Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Visual Research.” Monkey (Macaca fascicularis or M. mulatta) eyes, skeletal muscle, and heart were obtained from National Primate Centers or Lonza (Walkersville, MD) at necropsy from protocols not related to the present studies. Tissues were transported in CO2-independent medium on wet ice and processed within 36 h of being harvested. The globes were hemisected by a circumferential incision around the pars plana, and the anterior segment, lens, and vitreous were removed. After the neural retina was gently peeled away, RPE sheets were isolated from eyecups following incubation at 37°C with 1% dispase for 30 to 60 min as described previously (50). Tissues were snap frozen and stored at −80°C until use. For electrophysiology experiments, RPE cells were isolated enzymatically from pieces of fresh RPE-choroid using papain as described previously (14).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from RPE sheets and neural retina as described previously (51) and used for conventional reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis. PCR was performed with primers specific for human (h)KCNQ1–5 and GAPDH (Table 1). PCR products were obtained by cycling 40 times (35 times for GAPDH) as follows: 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 50–53°C, 1 min at 72°C, followed by a 7-min extension at 72°C. The PCR products were separated by 1.4% agarose gel electrophoresis. RPE samples were tested for retinal contamination using primers specific for rhodopsin (Table 1).

Table 1.

Target gene primer sequences and expected sizes of RT-PCR products

| Target Gene | Primer Sequence | Expected Size, bp | GenBank Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| KCNQ1 | |||

| Forward | 5′-CAC GGG GAC TCT CTT CTG GA-3′ | 427 | NM_000218 |

| Reverse | 5′-CAC GCG GCC TGA CTC GTT CA-3′ | ||

| KCNQ2 | |||

| Forward | 5′-GTA TGA GAA GAG CTC GGA G-3′ | 427 | XM_028859 |

| Reverse | 5′-GTC GTT CTC CCC CTT CTC TG-3′ | ||

| KCNQ3 | |||

| Forward | 5′-GAT GCA CAA GGA GAG GAG A-3′ | 452 | XM_005249 |

| Reverse | 5′-GTA TTG CTA CCA CGA GGA TTA GA-3′ | ||

| KCNQ4 | |||

| Forward | 5′-GTT TGA GCA CGT GCA ACG G-3′ | 444 | AF105202 |

| Reverse | 5′-ACA GCA GGC ATG ATG TCG-3′ | ||

| KCNQ5 | |||

| Forward | 5′-CAC AAA ATT GGC CTC AAG TTG-3′ | 717 | AF202977 |

| Reverse | 5′-GCA ATG GAA ACA GAT TTC TC-3′ | ||

| KCNQ4* | |||

| Forward | 5′-GGC CCT CTT GTT TGA GCA C-3′ | 230 | AF105202(v1) |

| Reverse | 5′-AGC TGC TGC TTG GAA GGA C-3′ | ||

| Forward | 5′-CAT CCT TCA GCA GCC GGA T-3′ | 206 | NM_172163(v2) |

| Reverse | 5′-GTC TCA GAG ATG CCC GGA AG-3′ | ||

| KCNQ5* | |||

| Forward | 5′-AAC CCA GCT GCC AAC CTC ATT C-3′ | 423 | NM_019842(v1) |

| Reverse | 5′-CAT CAC ACT GGC ATC CTT TTT CAT-3′ | 396 | NM_001160130(v2) |

| 453 | NM_001160132(v3) | ||

| Rhodopsin | |||

| Forward | 5′-CAT CGA GCG GTA CGT GGT GGT GTG-3′ | 577 | NM_000539 |

| Reverse | 5′-GCC GCA GCA GAT GGT GGT GAG C-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | |||

| Forward | 5′-GTG AAG GTC GGA GTC AAC G-3′ | 356 | AF261085 |

| Reverse | 5′-GAG ATG ATG ACC CTT TTG GC-3′ |

Primers for splice variants.

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization to frozen monkey retinal sections was carried out using digoxigenin-labeled cRNA probes prepared as follows. A 1.1-kb PCR product of KCNQ5 was generated from monkey retinal cDNA samples using hKCNQ5-specific primers (forward: 5′-CAC AAA ATT GGC CTC AAG TTG-3′; reverse: 5′- CAT CAC ACT GGC ATC CTT TTT CAT-3′) and cloned to pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI). The KCNQ5 insert sequence (nucleotides 803–1,845) was compared with published human KCNQ5_v2 sequence (NM_001160130). Digoxigenin-labeled antisense and sense riboprobes were synthesized using SP6 and T7 polymerase and a DIG RNA labeling kit (SP6/T7) (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Riboprobes were hybridized to retinal sections under moderately stringent conditions (55°C). Sections were incubated in staining buffer containing 2 μl/ml NBT/BCIP (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), 100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 9.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 50 mM MgCl2 at room temperature in the dark and checked periodically to evaluate the development of the alkaline phosphatase enzyme reaction. The reaction was stopped when the appropriate level of staining was achieved by rinsing sections in 0.1 M Tris-Cl (pH 8.0).

Transfection

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-M1WT3) and human embryonic kidney (HEK 293T) cell lines (both from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured according to the manufacturer's instructions. CHO-M1WT3 cells were transfected with the expression constructs pCMV6-XL5/KCNQ4 transcript variant 1 (GenBank accession no. NM_004700.2) or pCMV6-XL5/KCNQ4 transcript variant 2 (GenBank accession no. NM_172163.1) (both from OriGene Technologies) using Fugene6 Transfection Reagent (Roche Diagnostics), according to the manufacturer's protocol. HEK 293T cells were transfected with pCMV6-XL4/KCNQ5 transcript variant 1 (GenBank accession no. NM_019842.2) (OriGene Technologies) using the method mentioned above. Whole cell extracts were prepared for Western blot analysis 72 h after transfection. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay based on the method of Bradford (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Preparation of Monkey Heart, Skeletal Muscle, and RPE Plasma Membrane, and Neural Retina Crude Membrane Proteins

All protein procedures were performed at 4°C. Monkey heart and skeletal muscle plasma membranes were isolated according to methods previously published (9, 45). Membranes were stored at −80°C until use.

The plasma membranes of monkey RPE were isolated as previously described (27) with some modifications. Briefly, RPE sheets from 30 monkey eyes were homogenized in 100 ml of 0.25 M sucrose plus homogenizing buffer [0.025 M Tris-acetate pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce, Rockford, IL)] and then centrifuged at 27,000 g for 20 min. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 150,000 g for 1 h. The resulting pellet, homogenized in 5 ml of 57% sucrose containing homogenizing buffer, was placed at the bottom of clear tube and overlaid with 5 ml of 34% sucrose and 5 ml of 8.5% sucrose in homogenizing buffer. The sucrose gradient was centrifuged for 20 h at 75,500 g. Two fractions between the 8.5% and 57% overlayers were collected, diluted with homogenizing buffer, and centrifuged again at 150,000 g for 1 h. The pellets were resuspended with 200 μl of homogenizing buffer and stored at −80°C until use.

Crude membranes of monkey neural retina were prepared as previously described with slight modifications (42). Three frozen monkey neural retinas were homogenized in 10 ml homogenizing buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail). Cell debris and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 1,000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was separated into a soluble fraction and crude membrane protein pellet by centrifugation at 100,000 g for 30 min. The crude neural retina membrane protein pellet was suspended with 350 μl of homogenizing buffer, the protein concentration was determined, and the pellet was stored at −80°C until use.

Antibodies

Primary antibodies used in this study are listed in Table 2. Secondary antibodies used include donkey anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP; catalog no. sc-2314) and donkey anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (catalog no. sc-2313) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and Alexa Fluor488 goat anti-rabbit (H+L) and Alexa Fluor555 goat anti-mouse (H+L) from Invitrogen (Camarillo, CA).

Table 2.

Primary antibodies

| Antibody | Source | Catalog No. | Epitope | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na-K-ATPase α-1 subunit | Abcam | Ab7671 | Rabbit | Mouse monoclonal |

| CD29 | Biolegend | 303002 | Human | Mouse monoclonal |

| KCNQ1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-10646 | COOH terminus human | Goat polyclonal |

| C-20 | ||||

| KCNQ4 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-9385 | NH2 terminus human | Goat polyclonal |

| N-20 | ||||

| KCNQ4 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-20882 | COOH terminus rat | Goat polyclonal |

| G-14 | ||||

| KCNQ5 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-50416 | aa 727-896 Human | Rabbit polyclonal |

| H-170 | ||||

| KCNQ5 | ABR | PA1-941 | aa 880-897 Human | Rabbit polyclonal |

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed using the techniques described previously (54) with minor modifications. Briefly, proteins were mixed in Laemmli sample buffer [62.5 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 25% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.01% bromophenol blue, and 5% 2-mercaptoethanol; Bio-Rad] at room temperature for 20 min and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min. Proteins (10–20 μg) were applied to a 4% to 20% linear gradient Tris·HCl gel (Bio-Rad). After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad) at a constant current of 350 mA for 90 min at 4°C in a solution containing 25 mM Tris, 193 mM glycine, and 10% methanol. The membrane was then incubated at room temperature first with Tris-buffered saline containing 5% nonfat dried milk and 0.1% Tween 20 and then with primary antibodies at working dilutions of 1:1,000 (anti-Na-K-ATPase, anti-CD29), 1:500 (anti-KCNQ1, anti-KCNQ4), or 1:750 (anti-KCNQ5). Immune complexes were detected with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies at a dilution of 1:2,500 and enhanced with chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce). In experiments testing antibody specificity, antibodies plus 20-fold excess antigenic peptide were prepared at 4°C 1 day before use. Blots probed with antibody alone and with antibody preabsorbed with antigenic peptide were processed in parallel.

Immunohistochemistry

Pieces of monkey retina-RPE-choroid were fixed by immersion for 1 h in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) and then washed in chilled PB (3×, 20 min). To cryoprotect before freezing, tissues were incubated in successive 1-h incubations in 5% and 10% sucrose solutions in PB, then in 20% sucrose in PB overnight at 4°C. Tissues were embedded in optimal cutting temperature embedding medium (Tissue-Tek; Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections (10 or 20 μm) were cut, collected on glass slides, dried at room temperature, and stored at −80°C until use. For immunofluorescence labeling, cryosections were blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% normal goat serum, 1% BSA, and 0.3% Triton X-100 and then incubated overnight at 4°C in PBS containing primary antibodies (KCNQ1, 1:100 dilution; KCNQ4, 1:100 dilution; KCNQ5, 1:500 dilution; CD29, 1:100 dilution) plus 2% normal goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100. Sections were washed eight times and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 1 h with two mixed secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor488 goat anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor555 goat anti-mouse) diluted in 0.2% Triton X-100 and 2% normal goat serum in PBS to a final dilution of 1:500. After being washed eight times in the dark, sections were covered in mounting medium (Gel Mount; Bio-Meda) and secured with a coverslip.

Specimens were analyzed on a scanning laser confocal microscope (Leica SP5, Mannheim, Germany). Digital images were collected at 16-bit resolution in 0.29-μm z-sections and analyzed by image analysis software (Leica LAS AF). The confocal immunofluorescence images in Fig. 6 are three-dimensional projections generated from four to eight consecutive z-sections. Files were exported for additional processing by Photoshop CS2 (Adobe, San Jose, CA). In experiments testing antibody specificity by preabsorption with antigenic peptide, laser settings, photomultiplier tube gain, exposure time, and brightness and contrast settings were identical for both experimental and control images.

Fig. 6.

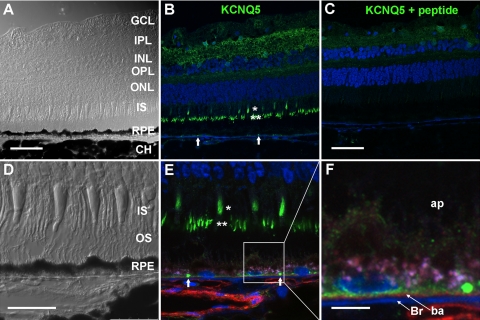

Immunofluorescence localization of KCNQ5 protein in monkey retina. A and B: differential interference contrast (DIC, A) and confocal immunofluorescence image (B) of a monkey neural retina-RPE-choroid (CH) cryosection labeled with anti-KCNQ5 antibody (green). Anti-KCNQ5 antibody labeled the inner plexiform layer (IPL) and outer plexiform layer (OPL), cone (single asterisk), and rod (double asterisk) photoreceptor inner segments (IS), and punctate structures near the RPE basal membrane (block arrows). DAPI-labeled cell nuclei are shown in blue, as is Bruch's membrane, which exhibits autofluorescence in the blue emission channel. Scale bars, 50 μm. C: specificity of anti-KCNQ5 antibody: confocal immunofluorescence image of a cryosection from the same tissue as that depicted in A and B, but processed with anti-KCNQ5 antibody preabsorbed with antigenic peptide. Immunofluorescence labeling in the neural and RPE was reduced or eliminated. Scale bar, 50 μm. D–F: subcellular localization of KCNQ5 in the distal retina: DIC (D) and confocal immunofluorescence image (E) of a cryosectioned neural retina-RPE-choroid from a different monkey double-labeled with anti-KCNQ5 (green) and anti-CD29 (red) antibodies. DAPI-labeled cell nuclei are shown in blue. Single and double asterisks indicate the location of cone and rod photoreceptor inner segments, respectively, and solid arrows point to regions of punctate KCNQ5 staining. OS, outer segments. Scale bar, 25 μm. F: inset indicated by the box in E showing KCNQ5 distribution in the RPE at higher magnification. KCNQ5 immunolabeling is present near the basal membrane (ba) above Bruch's membrane (Br, blue). Note that much of KCNQ5 does not colocalize with CD29 (red), perhaps reflecting its distribution in basal infoldings. Lipofuscin appears light purple. ap, Apical membrane. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Electrophysiology

Enzymatically dissociated monkey RPE cells were plated on the bottom of a recording chamber that was constantly perfused with HEPES-buffered Ringer solution consisting of (in mM) 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 Na2HEPES, 10 glucose, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, pH 7.4 (290 mosM). Whole cell currents were recorded at room temperature from single RPE cells using the whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique as described previously (14). Pipettes were filled with pipette solution containing (in mM) 30 KCl, 83 K-gluconate, 10 K2HEPES, 5.5 K2EGTA, 0.5 CaCl2, 4 MgCl2, 4 mM K2ATP, 0.5 mM Na2GTP, pH 7.2. Series resistance (Rs) was normally <5 MΩ and was uncompensated. Patch electrodes were pulled from 1.65 mm OD glass capillary tubing (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) using a multistage programmable microelectrode puller (model P-97, Sutter Instruments, San Rafael, CA) and had an impedance of 2–5 MΩ after fire polishing. Signals were amplified with an Axopatch 200 amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Data acquisition and analysis were carried out using pClamp 9 (Molecular Devices). Statistical analysis and curve fitting were performed using Excel (Microsoft) and SigmaPlot 10 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Tail current analysis was used to determine the M-type conductance, as described previously (43).

RESULTS

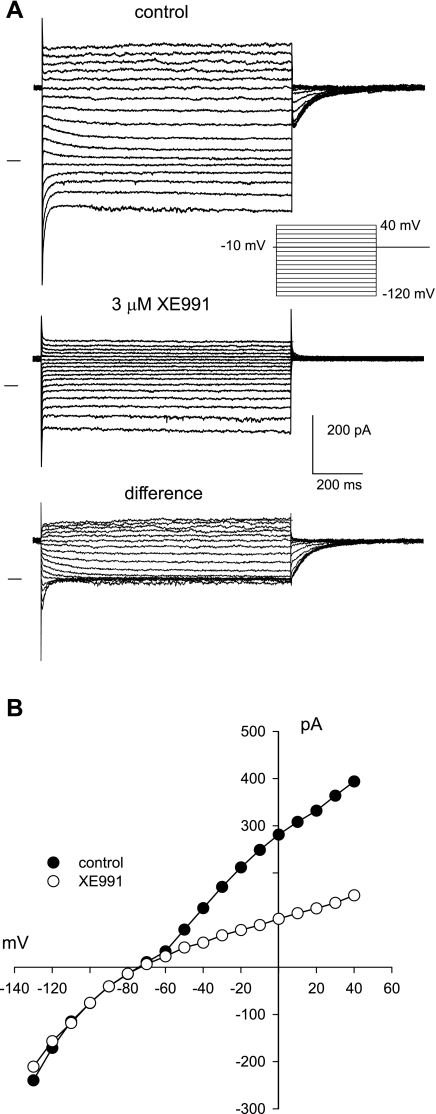

M-Type Current in the RPE Cells Is Sensitive to Block by XE991

Previous studies on freshly isolated human and bovine RPE cells identified an outwardly rectifying K+ current with kinetic properties similar to those of M-type currents in excitable cells (14, 43). To determine whether the M-type current in the RPE is mediated by KCNQ channels, we tested the effects of XE991, a blocker that is specific against KCNQ/Kv7 channels when used in the micromolar range (6, 30). Figure 1 shows the effects of 3 μM XE991 on whole cell currents in an isolated monkey RPE cell. Under control conditions (Fig. 1A, top), membrane hyperpolarizations from a holding potential of −10 mV elicited current relaxations resulting from the deactivation of M-type channels and repolarizations to the holding potential produced characteristic tail currents reflecting channel activation (43). Superfusion of the cell with 3 μM XE991 eliminated the time-dependent current (Fig. 1A, middle) and outwardly rectifying current voltage relationship (Fig. 1B), unmasking an inwardly rectifying K+ current (Kir) likely mediated by Kir7.1 channels (50). Similar results were obtained in other cells; in three cells, 3 μM XE991 blocked 93 ± 2% (means ± SE) of the M-type conductance and in four others, 10 μM XE991 blocked the M-type conductance by 99 ± 3%. These results provide strong evidence that KCNQ channels are the basis for the M-type current in the RPE.

Fig. 1.

M-type current in monkey retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells is blocked by the KCNQ channel blocker XE991. A: whole cell currents in the absence (top) and presence (middle) of 3 μM XE991. The XE991-sensitive component of whole cell current (bottom) shows the isolated M-type current. Currents were evoked from a holding potential of −10 mV by voltage steps ranging from −120 mV to 40 mV, as indicated. Horizontal lines indicate the zero-current levels. B: current-voltage relationship of the steady-state currents depicted in A. Note that XE991 specifically blocked the outwardly rectifying component of whole cell current.

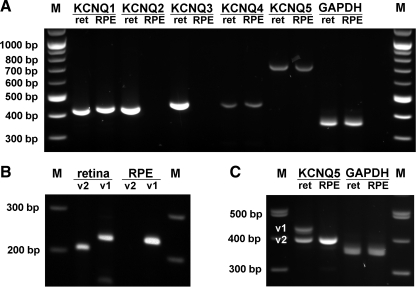

KCNQ mRNA Expression in RPE and Neural Retina

As a first step toward determining the specific KCNQ subunit(s) that compose the M-type channel in the RPE, we performed conventional RT-PCR analysis using mRNA isolated from monkey RPE and KCNQ subunit-specific primers (Table 1). Reactions using mRNA from neural retina served as positive controls. In monkey RPE, KCNQ1, KCNQ4, and KCNQ5 transcripts were detected, whereas in monkey retina, transcripts for all five KCNQ subunits were identified (Fig. 2A). Positive PCR fragments were sequenced, and a comparison of sequenced products with published human sequences confirmed their identities.

Fig. 2.

KCNQ subunit mRNA expression in monkey neural retina and RPE. A: total RNA isolated from macaque neural retina (ret) and RPE was used in conjunction with KCNQ subunit-specific primers (Table 1) for RT-PCR analysis of KCNQ subunit transcript expression. Neural retina expresses all five KCNQ channels, whereas the RPE expresses KCNQ1, KCNQ4, and KCNQ5. B: KCNQ4 splice variant expression in monkey neural retina and RPE. Both KCNQ4_v1 and _v2 are expressed in neural retina, whereas only KCNQ4_v1 is expressed in the RPE. C: KCNQ5 splice variant expression in monkey neural retina and RPE. KCNQ5_v1 and v2 are expressed in the neural retina, whereas only KCNQ5_v2 is expressed in the RPE. All bands were sequenced to confirm their identities.

Alternative splicing of KCNQ genes contributes to diversity in KV7 channel function and expression. There are two physiologically relevant splice variants of KCNQ1, a long isoform (KCNQ1_v1) that contributes to voltage-gated K+ channels underlying slowly inactivating current (IKs) in heart, and a shorter isoform (KCNQ1_v2) with a truncated NH2 terminus that is nonconductive and dominant negative when coexpressed with KCNQ1_v1 (19). Because KCNQ1 protein could not be detected in either the RPE or neural retina (see below), we did not investigate KCNQ1 transcripts in further detail.

Two splice variants have been reported for human KCNQ4 (4) and three splice variants have been reported for KCNQ5 (39). Using splice variant-specific primers (Table 1), PCR of monkey retina cDNA produced appropriately sized bands for KCNQ4 variants 1 and 2 (_v1 and _v2), whereas a single band corresponding to KCNQ4_v1 was produced from monkey RPE cDNA (Fig. 2B). KCNQ5 has in the region coding for the COOH terminus a splice site that generates three variants that vary in size (39). To clarify the expression of KCNQ5 splice variants in monkey retina and RPE, we designed a single primer set that spans this variable region. PCR of monkey retina cDNA produced two bands corresponding to KCNQ5_v1 and v2, whereas only a single band corresponding to KCNQ5_v2 was produced when monkey RPE cDNA was used as template (Fig. 2C).

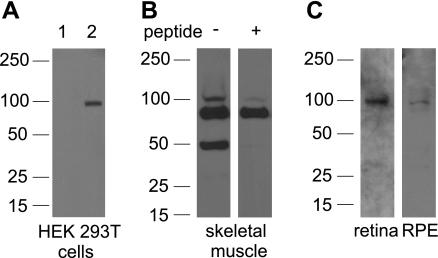

KCNQ Protein Expression in RPE and Neural Retina

To examine the expression of KCNQ1, KCNQ4, and KCNQ5 subunits in the RPE and neural retina at the protein level, we performed gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis. In preliminary experiments using commercially available antibodies against KCNQ1, KCNQ4, and KCNQ5 (Table 2), we were unable to detect any of these subunits in crude membrane proteins from RPE, indicating that, if present, they were a relatively small fraction of total membrane proteins or that the antibodies were not sensitive enough to detect KCNQ subunit proteins. Consequently, we performed subsequent Western blot analysis using plasma membrane proteins pooled from RPE sheets collected from 30 monkey eyes.

To evaluate the quality of the RPE plasma membrane protein sample, we performed Western blot analysis using anti-Na-K-ATPase α-subunit (50) and anti-CD29 antibodies (28) as markers of the apical and basolateral membranes, respectively. The anti-Na-K-ATPase and anti-CD29 antibodies labeled bands of the appropriate size (not shown), confirming that the sample contained both apical and basolateral membrane proteins.

KCNQ1.

We used a goat polyclonal anti-KCNQ1 antibody (Santa Cruz C-20) that has been previously characterized and shown to label appropriately sized bands in various tissues and in mammalian cell lines transfected with human KCNQ1 (12, 37). To determine the reactivity of the anti-KCNQ1 antibody in monkey, we tested it in Western blots of monkey heart plasma membrane protein and found that it labeled a single band of ∼78 kDa (data not shown), the expected molecular mass of a KCNQ1 monomer. Preabsorption of the anti-KCNQ1 antibody with antigenic peptide reduced the degree of immunolabeling of the 78 kDa band, confirming the specific reactivity of the antibody with monkey KCNQ1. In blots of crude membrane proteins from monkey neural retina or plasma membrane proteins from monkey RPE, however, KCNQ1 protein was not detected (data not shown).

KCNQ4.

We characterized a goat polyclonal antibody raised against the NH2 terminus of human KCNQ4 (Santa Cruz N-20) in Western blots of whole cell lysates of CHO cells transfected with recombinant human KCNQ4 splice variant 1 (_v1) or 2 (_v2). The antibody labeled appropriately sized bands (∼77 kDa) in blots of lysates from both KCNQ4_v1-transfected (Fig. 3A, lane 2) and KCNQ4_v2-transfected cells (Fig. 3A, lane 3), but failed to label a band in lysates from untransfected cell samples (Fig. 3A, lane 1). Our results indicate that this KCNQ4 antibody can detect both human KCNQ4_v1 and _v2.

Fig. 3.

KCNQ4 protein expression in neural retina and RPE. A: anti-KCNQ4 antibody immunolabeled a ∼77 kDa band in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with KCNQ4_v1 (lane 2) or KCNQ4_v2 (lane 3), but not in untransfected cells (lane 1). B: in retina crude membrane protein, anti-KCNQ4 antibody labeled ∼77 and ∼154 kDa bands (left), which were diminished after the antibody was preabsorbed with antigenic peptide (right). C: KCNQ4 was not detected in blots of RPE plasma membrane. Results are representative of more than 3 separate experiments.

In neural retina, the anti-KCNQ4 antibody recognized a band of ∼77 kDa and a broad smear between ∼100 and 250 kDa (Fig. 3B). The presence of the ∼77 kDa band is consistent with the labeling of a KCNQ4 monomer, but the similar molecular masses of KCNQ4_v1 and _v2 (∼77 kDa and ∼71 kDa, respectively) do not allow us to specify which splice variant is expressed. Preabsorption of the antibody with antigenic peptide reduced the labeling of the ∼77 kDa (Fig. 3B), indicating that the antibody recognized monkey KCNQ4 protein. It is clear that the higher molecular mass smear is not KCNQ4 because antigen preabsorption of the antibody did not decrease the band. The smear bands of 100 to 150 kDa may be caused by aggregation of KCNQ4 with other proteins or a KCNQ4 dimer since these bands were lightly eliminated by antigen preabsorption. In contrast, the anti-KCNQ4 antibody did not label any band in the RPE (Fig. 3C). Similar results in neural retina and RPE were obtained using a goat polyclonal antibody raised against a polypeptide in the rat KCNQ4 COOH terminus (G-14, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; data not shown).

KCNQ5.

We characterized a rabbit polyclonal anti-KCNQ5 antibody raised against the human KCNQ5 NH2 terminus (PA1-94-1, ABR) in Western blot analysis using lysates from HEK 293T cells transfected with recombinant human KCNQ5_v1 and found that it labeled an appropriately sized band of ∼100 kDa (Fig. 4A). In blots of plasma membrane proteins from monkey skeletal muscle, where KCNQ5 expression has been documented (39), the anti-KCNQ5 antibody labeled ∼50, ∼75, and ∼100 kDa bands (Fig. 4B, left lane). Preabsorption of the antibody with antigenic peptide diminished or eliminated the 50 and 100 kDa bands (Fig. 4B, right lane), indicating reactivity of the antibody with monkey KCNQ5 protein. As the expected molecular mass of a KCNQ5 monomer is ∼100 kDa, the ∼50 kDa band is likely a protein degradation product. Figure 4C shows that the anti-KCNQ5 antibody also detected bands of ∼100 kDa in neural retina and RPE. Another rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against the COOH terminus of human KCNQ5 (H-170, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) also labeled ∼100 kDa bands in retina and RPE (results not shown), but the identification of these bands as KCNQ5 was not possible due to the lack of an antigenic peptide.

Fig. 4.

KCNQ5 protein expression in neural retina and RPE. A: anti-KCNQ5 antibody recognized an appropriately sized band of ∼100 kDa (expected molecular mass, 103 kDa) in lysates from human embryonic kidney (HEK 293T) cells transfected with KCNQ5 (lane 2), but not in untransfected cells (lane 1). B: anti-KCNQ5 antibody immunolabeled a ∼100 kDa band in monkey skeletal muscle plasma membrane (left), as well as ∼75 and ∼50 kDa bands. Immunoreactivity of the ∼100 and ∼50 kDa bands was greatly reduced after preabsorption of the antibody with antigenic peptide (right). C: KCNQ5 antibody immunolabeled ∼100 kDa bands in monkey neural retina crude membrane and RPE plasma membrane proteins. Results are representative of more than 3 separate experiments.

In summary, our results show that both KCNQ4 and KCNQ5 proteins are expressed in the monkey neural retina and that in the RPE, only KCNQ5 is expressed at a detectable level.

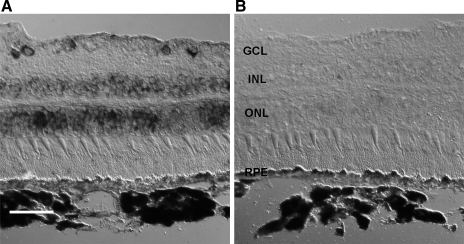

Localization of KCNQ5 Transcripts in Monkey Retina

To determine the cellular distribution of KCNQ5 in the retina, we performed in situ hybridization on frozen adult monkey retina sections using an antisense probe recognizing a 1,042-bp segment of the coding sequence. Figure 5 shows a differential interference contrast (DIC) photomicrograph of a monkey retina section hybridized with antisense probe. A strong hybridization signal was observed in the outer nuclear layer (ONL), which contains the cell bodies of rod and cone photoreceptors, in the inner nuclear layer (INL), which includes the cell bodies of bipolar, amacrine, horizontal, and Müller cells, and also in some of the cell bodies located in the ganglion cell layer (GCL; Fig. 5A). Despite our detection of KCNQ5 in purified RPE sheets by RT-PCR (Fig. 2), a hybridization signal could not be seen in the RPE, perhaps because it was obscured by melanin. In situ hybridization with the complementary sense probe demonstrated no detectable signal (Fig. 5B). Hence, KCNQ5 transcript appears to be present in most retinal neurons and the RPE as well.

Fig. 5.

Localization of KCNQ5 message in monkey retina. In situ hybridization to sections of monkey retina with antisense (A) and sense (B) digoxigenin-labeled monkey KCNQ5 riboprobes. Specific expression is seen in the ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner nuclear layer (INL), and outer nuclear layer (ONL). Melanin may have obscured KCNQ5 signal in the RPE. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Immunofluorescence Localization of KCNQ5 Protein in Monkey Retina

To localize KCNQ1, KCNQ4, and KCNQ5 proteins in RPE and neural retina, we performed confocal immunofluorescence microscopy on frozen sections of monkey retina using the anti-KCNQ antibodies that we characterized by Western blot analysis (Figs. 3 and 4). Sections were double-labeled with antibodies against CD29, a member of the integrin family (β1-integrin), which has been localized to the RPE basolateral membrane as well as to retinal and choroidal blood vessels (28, 34).

Neither the anti-KCNQ1 antibody (Santa Cruz C-20) nor the anti-KCNQ4 antibodies (N-20, G-14) labeled the neural retina, RPE, or choroid (not shown), indicating that the proteins were in low abundance or that these antibodies do not work in fixed monkey tissue. On the other hand, the anti-KCNQ5 antibody consistently immunolabeled structures in both the RPE and retina. Figure 6B shows KCNQ5 immunolabeling of puncta at the basal aspect of the RPE (block arrows) as well as strong immunolabeling of rod (indicated by the double asterisks) and cone photoreceptor (indicated by the single asterisk) inner segments. Diffuse KCNQ5 immunoreactivity was also observed in the inner (IPL) and outer (OPL) plexiform layers, in some cell bodies in the INL and GCL, and in occasionally in retinal blood vessels (not shown). Immunolabeling in both the RPE and neural retina was reduced or eliminated when the antibody was preabsorbed with antigenic peptide (Fig. 6C). At higher magnification, diffuse as well as punctate immunoreactivity was observed near the RPE basal membrane (Fig. 6, E and F). The basal membrane also exhibited diffuse CD29 immunostaining (Fig. 6, E and F), but, interestingly, KCNQ5 immunostaining appeared to lie on the cytoplasmic side of the CD29 signal, perhaps reflecting KCNQ5 expression in the basal infoldings (36). A rabbit antibody against human KCNQ5 NH2 terminus (a gift of A. Villarroel, Leioa, Spain) produced a similar staining pattern of rod and cone photoreceptor inner segments and RPE (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies identified an M-type K+ current in mammalian RPE cells (14, 43, 47). However, the subunit composition of the underlying channel has remained unknown. In the present study, we demonstrated that the M-type current in monkey RPE cells is inhibited by the specific KCNQ channel blocker XE991 and investigated the expression of KCNQ subunits in monkey RPE and neural retina at the mRNA and protein levels by molecular, biochemical, and immunohistochemical approaches. This is the first comprehensive survey of KCNQ expression in the RPE or neural retina of any species. A major finding of this study is that KCNQ5 protein is expressed in primate RPE and neural retina and that it is localized near the RPE basal membrane as well as in cone and rod photoreceptor inner segments.

As a first step toward defining the expression of KCNQ channels in the retina, we performed RT-PCR analysis on monkey neural retina and isolated RPE sheets. This revealed the expression of KCNQ1-Q5 in the neural retina and KCNQ1, KCNQ4, and KCNQ5 transcripts in the RPE.

Six alternative splice variants of human KCNQ1 have been reported that differ depending on the use of exons in the 5′-end of the gene, but only splice variants 1 and 2 are thought to be physiologically relevant: KCNQ1_v1 coassembles with the β-subunit KCNE1 to form IKs channels in the heart or with KCNE2 or KCNE3 to form constitutively active K+ channels that depend linearly on voltage in certain epithelia (40, 44). KCNQ1_v2 lacks 127 amino acids in the NH2 terminus, is nonconducting, and has dominant-negative effects on KCNQ1_v1 channels (19). We did not determine which KCNQ1 splice variants are expressed in the RPE or neural retina, but this issue should be explored in future studies.

Using splice variant specific primers, we determined that the RPE expresses KCNQ4_v1 transcript alone, whereas the neural retina expresses both KCNQ4_v1 and _v2 transcripts. Human KCNQ4_v1 and _v2 are identical except that KCNQ4_v2 lacks exon 9, resulting in the deletion of 54 amino acids in a membrane proximal region of the COOH terminus. Although originally thought to have restricted expression in the central and peripheral auditory system (22, 23), KCNQ4 is now known to have a wider tissue distribution: in mouse, mKCNQ4_v1 is expressed in a variety of tissues, whereas the mouse ortholog of hKCNQ4_v2 (mKCNQ4_v4) is found predominantly in excitable tissues, including the neural retina (4). Patch-clamp studies have shown that, compared with mKCNQ4_v1 channels, mKCNQ4_v4 channels activate at more negative voltages and are expressed at higher levels (48). It is currently not known whether the human KCNQ4_v1 and _v2 also differ in terms of voltage sensitivity and surface expression.

We also investigated which of the three known splice variants of KCNQ5 are expressed in the RPE and neural retina using primers for KCNQ5 that span a splice site in the region coding for the COOH terminus. We found that the RPE expresses KCNQ5_v2 and that the neural retina expresses KCNQ5_v1 and _v2. Initial studies identifying KCNQ5 indicated that it is expressed mainly in brain and skeletal muscle (25, 39). KCNQ5_v1, which encodes a protein 932 amino acids long, apparently is the only variant expressed in brain (39, 53), whereas in skeletal muscle, KCNQ5_v2, which translates into a protein with a truncation of 9 amino acids in the vicinity of calmodulin and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) binding domains, and KCNQ5_v3, which contains 19 additional amino acids, are also expressed (53).

We performed Western blot analysis of monkey RPE plasma membrane and retinal crude membrane proteins for the three KCNQ subunits that were detected in the RPE by RT-PCR. In the neural retina, we detected KCNQ4 and KCNQ5 proteins, but not KCNQ1, whereas in the RPE we detected only KCNQ5 protein. The failure to detect KCNQ1 protein in neural retina and RPE was not due to a lack of antibody reactivity with monkey protein because in Western blots of monkey heart protein the antibody stained a prominent band with a molecular mass consistent with a KCNQ1 monomer and because this immunolabeling was eliminated by preincubation of the antibody with antigenic peptide. We cannot exclude, however, the possibility that KCNQ1 protein is expressed in the neural retina and RPE at levels too low to be detected with the antibody we used. Likewise, the antibody against KCNQ4 recognized monkey KCNQ4 protein in Western blots, as it labeled an appropriately sized band in neural retina that was diminished after preabsorption with antigenic peptide; it failed, however, to reveal the presence of KCNQ4 protein in the RPE.

Our immunofluorescence studies on frozen sections of monkey retina also failed to reveal KCNQ1 or KCNQ4 protein expression in monkey neural retina or RPE, perhaps because the antibodies used do not recognize the epitopes in fixed monkey tissue. We conclude that KCNQ5 protein is expressed in monkey RPE and that KCNQ1 and KCNQ4, if expressed, are present at levels below detection. Additional studies investigating the expression of KCNQ1 and KCNQ4 in the RPE and neural retina are warranted.

In situ hybridization experiments to sections of monkey retina indicated the presence of KCNQ5 transcripts in the perinuclear regions of photoreceptors as well as some cell bodies in the inner nuclear layer and ganglion cell layer. KCNQ5 transcript expression in the RPE could not be determined by this method due to the presence of melanin, but our PCR results using cDNA from isolated RPE sheets established that KCNQ5 is expressed in this tissue.

Immunofluorescence experiments using antibodies against a peptide sequence in the human KCNQ5 COOH terminus revealed a more limited expression pattern for KCNQ5 protein in monkey retina. KCNQ5 immunoreactivity was prominent in rod and cone photoreceptor inner segments and was more weakly expressed in the inner and outer plexiform layers. In the RPE, diffuse KCNQ5 immunostaining was observed near the basal membrane. The staining pattern of KCNQ5 in the RPE was similar to but not identical to that of CD29 (Fig. 6F), a marker of RPE basal membrane (28, 29). CD29 staining appeared to be limited to a region adjacent to Bruch's membrane, whereas KCNQ5 immunoreactivity extended somewhat deeper into the cytoplasm. The reason for this difference is unclear, but it may reflect expression of the integrin at regions of contact between the RPE basal membrane and Bruch's membrane on the one hand and the distribution of KCNQ5 in the basal infoldings on the other. In addition to diffuse staining, the anti-KCNQ5 antibody immunolabeled punctuate structures near the RPE basal membrane. It is tempting to speculate that structures represent the aggregation of KCNQ5 channels in specialized membrane domains, but more detailed experiments are needed to test this idea.

Previously, we and others identified a sustained outward K+ current in acutely dissociated human and monkey RPE cells that is kinetically similar to the M-current (14, 47). The M-type current in primate RPE has a half-maximal activation voltage (V0.5) of −37 mV and is blocked by barium but is relatively insensitive to block by extracellular TEA (14). In the present study, we found that low doses of the KCNQ/Kv7 channel blocker XE991 eliminated the M-type current in freshly isolated monkey RPE cells. Although this result provides strong evidence that the current is mediated by KCNQ channels, it does not indicate which subunits expressed in the RPE are involved, as XE991 exhibits minimal selectivity against channels formed by various KCNQ subunits (30). On the other hand, the voltage dependence and TEA insensitivity of the M-type current are inconsistent channels composed of KCNQ1 subunits (18), but are compatible with homomeric KCNQ4_v1 and KCNQ5_v1 channels, which have V0.5 values of −27 mV and −31 mV (26), respectively, and low sensitivities to block by TEA (2). KCNQ5_v2, the KCNQ5 variant expressed in the RPE, has biophysical and pharmacological properties similar to those of KCNQ5_v1 (53), and although its TEA sensitivity has not been determined, the truncation of nine amino acids in its COOH terminus is not likely to affect sensitivity to this blocker (2). It has been suggested that KCNQ5v_2 may differ from other KCNQ5 splice variants in terms of its regulation by Ca-calmodulin or PIP2 (53), and it will be interesting to determine how KCNQ5_v2 channels and native M-type channels in the RPE are modulated by these signaling pathways. If KCNQ4 and KCNQ5 subunits are expressed in the same RPE cells, they may exist as KCNQ4/Q5 heteromeric channels, as studies have demonstrated that these subunits are capable of coassembling (2). Future studies should investigate this possibility as well as the potential contributions to the channel(s) by β-subunits encoded by the KCNE gene family.

Mutations in KCNQ1 and KCNQ4 genes underlie a number of inherited diseases in humans, including cardiac arrhythmia and nonsyndromal deafness (38), but no disease has been linked to mutations of KCNQ5. Interestingly, no visual disorder has been linked to KCNQ1 or KCNQ4 mutations that cause channelopathies in other tissues. This suggests that if they are expressed, KCNQ1 and KCNQ4 subunits likely play minor or redundant roles in RPE and neural retina physiology.

The active transport of K+ across the RPE in the apical-to-basal direction plays an important role in the regulation of subretinal K+ concentration and solute-linked fluid absorption. K+ absorption across the RPE involves the influx of K+ across the apical membrane via the Na-K pump and Na-K-2Cl cotransporter and its efflux across the basolateral membrane via a K+ conductance (20, 31) composed of Ba2+-sensitive K+ channels (15, 21, 32). Our findings that KCNQ5 is expressed in monkey RPE and is localized near the basal membrane suggest that KCNQ5 channels may contribute to the basolateral membrane K+ conductance. K+ channels in the RPE basolateral membrane have also been implicated in regulatory volume decrease (1). KCNQ4 (13) and KCNQ5 (16) channels are activated by increases in cell volume and thus may contribute to regulatory volume decrease in the RPE following cell swelling.

The activity of KCNQ channels is dependent on the levels of PIP2 in the plasma membrane and the stimulation of certain Gq/11-coupled receptors leads to the inhibition of M-type and KCNQ channels via activation of phospholipase C and depletion of membrane PIP2. Although a number of G protein-coupled receptors have been identified in the RPE apical membrane, it is not known whether this class of receptor is located in the basal membrane where the hydrolysis of membrane PIP2 secondary to their activation could potentially inhibit KCNQ5 channels.

An unexpected finding of this study was the strong KCNQ5 immunolabeling of cone and rod photoreceptor inner segments. This immunoreactivity appears to be specific for KCNQ5 because labeling was eliminated when the antibody was preabsorbed by antigenic peptide. Vertebrate rod photoreceptors express a sustained outwardly rectifying current called IKx (3), which serves to set the dark resting potential and accelerate the photoresponse to dim light. IKx resembles the M-current kinetically (24), leading to speculation that the underlying channel is composed of KCNQ subunits, but there is other evidence suggesting that the current is mediated at least in part by ether-a-go-go (EAG) channels (8). Patch-clamp studies of macaque cone inner segments have identified outwardly rectifying K+ currents that were partially blocked by 20 mM extracellular TEA (49). It remains to be determined whether KCNQ5 channels contribute to voltage-gated K+ currents in rod or cone inner segments or in retinal neurons.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant EY08850 and Core Grant EY07003, the Foundation Fighting Blindness, and Research to Prevent Blindness Lew R. Wasserman Merit Award (to B. A. Hughes).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Anuradha Swaminathan for contribution to preliminary experiments, Dr. Peter Hitchcock and Laura Kakuk-Atkins for help with in situ hybridization, Mitchell Gillette for assistance with retinal cryosectioning, and Dr. Stephen Lentz for assistance with confocal microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adorante JS. Regulatory volume decrease in frog retinal pigment epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 268: C89–C100, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bal M, Zhang J, Zaika O, Hernandez CC, Shapiro MS. Homomeric and heteromeric assembly of KCNQ (Kv7) K+ channels assayed by total internal reflection fluorescence/fluorescence resonance energy transfer and patch clamp analysis. J Biol Chem 283: 30668–30676, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beech DJ, Barnes S. Characterization of a voltage-gated K+ channel that accelerates the rod response to dim light. Neuron 3: 573–581, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beisel KW, Rocha-Sanchez SM, Morris KA, Nie L, Feng F, Kachar B, Yamoah EN, Fritzsch B. Differential expression of KCNQ4 in inner hair cells and sensory neurons is the basis of progressive high-frequency hearing loss. J Neurosci 25: 9285–9293, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown DA, Adams PR. Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neurone. Nature 283: 673–676, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown DA, Passmore GM. Neural KCNQ (Kv7) channels. Br J Pharmacol 156: 1185–1195, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Constanti A, Brown DA. M-currents in voltage-clamped mammalian sympathetic neurones. Neurosci Lett 24: 289–294, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frings S, Brull N, Dzeja C, Angele A, Hagen V, Kaupp UB, Baumann A. Characterization of ether-a-go-go channels present in photoreceptors reveals similarity to IKx, a K+ current in rod inner segments. J Gen Physiol 111: 583–599, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galante P, Mosthaf L, Kellerer M, Berti L, Tippmer S, Bossenmaier B, Fujiwara T, Okuno A, Horikoshi H, Haring HU. Acute hyperglycemia provides an insulin-independent inducer for GLUT4 translocation in C2C12 myotubes and rat skeletal muscle. Diabetes 44: 646–651, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gamper N, Li Y, Shapiro MS. Structural requirements for differential sensitivity of KCNQ K+ channels to modulation by Ca2+/calmodulin. Mol Biol Cell 16: 3538–3551, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gamper N, Stockand JD, Shapiro MS. Subunit-specific modulation of KCNQ potassium channels by Src tyrosine kinase. J Neurosci 23: 84–95, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horikawa N, Suzuki T, Uchiumi T, Minamimura T, Tsukada K, Takeguchi N, Sakai H. Cyclic AMP-dependent Cl− secretion induced by thromboxane A2 in isolated human colon. J Physiol 562: 885–897, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hougaard C, Klaerke DA, Hoffmann EK, Olesen SP, Jorgensen NK. Modulation of KCNQ4 channel activity by changes in cell volume. Biochim Biophys Acta 1660: 1–6, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hughes BA, Takahira M, Segawa Y. An outwardly rectifying K+ current active near resting potential in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 269: C179–C187, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Immel J, Steinberg RH. Spatial buffering of K+ by the retinal pigment epithelium in frog. J Neurosci 6: 3197–3204, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jensen HS, Callo K, Jespersen T, Jensen BS, Olesen SP. The KCNQ5 potassium channel from mouse: a broadly expressed M-current like potassium channel modulated by zinc, pH, and volume changes. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 139: 52–62, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jentsch TJ. Neuronal KCNQ potassium channels: physiology and role in disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 1: 21–30, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jespersen T, Grunnet M, Olesen SP. The KCNQ1 potassium channel: from gene to physiological function. Physiology (Bethesda) 20: 408–416, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jiang M, Tseng-Crank J, Tseng GN. Suppression of slow delayed rectifier current by a truncated isoform of KvLQT1 cloned from normal human heart. J Biol Chem 272: 24109–24112, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Joseph DP, Miller SS. Alpha-1-adrenergic modulation of K and Cl transport in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. J Gen Physiol 99: 263–290, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joseph DP, Miller SS. Apical and basal membrane ion transport mechanisms in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. J Physiol 435: 439–463, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kharkovets T, Dedek K, Maier H, Schweizer M, Khimich D, Nouvian R, Vardanyan V, Leuwer R, Moser T, Jentsch TJ. Mice with altered KCNQ4 K+ channels implicate sensory outer hair cells in human progressive deafness. EMBO J 25: 642–652, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kubisch C, Schroeder BC, Friedrich T, Lutjohann B, El-Amraoui A, Marlin S, Petit C, Jentsch TJ. KCNQ4, a novel potassium channel expressed in sensory outer hair cells, is mutated in dominant deafness. Cell 96: 437–446, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kurenny DE, Barnes S. Proton modulation of M-like potassium current (IKx) in rod photoreceptors. Neurosci Lett 170: 225–228, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lerche C, Scherer CR, Seebohm G, Derst C, Wei AD, Busch AE, Steinmeyer K. Molecular cloning and functional expression of KCNQ5, a potassium channel subunit that may contribute to neuronal M-current diversity. J Biol Chem 275: 22395–22400, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li Y, Gamper N, Shapiro MS. Single-channel analysis of KCNQ K+ channels reveals the mechanism of augmentation by a cysteine-modifying reagent. J Neurosci 24: 5079–5090, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mata NL, Villazana ET, Tsin AT. Colocalization of 11-cis retinyl esters and retinyl ester hydrolase activity in retinal pigment epithelium plasma membrane. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 39: 1312–1319, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McLaughlin BJ, Fan W, Zheng JJ, Cai H, Del Priore LV, Bora NS, Kaplan HJ. Novel role for a complement regulatory protein (CD46) in retinal pigment epithelial adhesion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 3669–3674, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Menko AS, Philip NJ. Beta 1 integrins in epithelial tissues: a unique distribution in the lens. Exp Cell Res 218: 516–521, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miceli F, Soldovieri MV, Martire M, Taglialatela M. Molecular pharmacology and therapeutic potential of neuronal Kv7-modulating drugs. Curr Opin Pharmacol 8: 65–74, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miller SS, Edelman JL. Active ion transport pathways in the bovine retinal pigment epithelium. J Physiol 424: 283–300, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miller SS, Steinberg RH. Passive ionic properties of frog retinal pigment epithelium. J Membr Biol 36: 337–372, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moser SL, Harron SA, Crack J, Fawcett JP, Cowley EA. Multiple KCNQ potassium channel subtypes mediate basal anion secretion from the human airway epithelial cell line Calu-3. J Membr Biol 221: 153–163, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mullins RF, Kuehn MH, Faidley EA, Syed NA, Stone EM. Differential macular and peripheral expression of bestrophin in human eyes and its implication for best disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48: 3372–3380, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Neyroud N, Tesson F, Denjoy I, Leibovici M, Donger C, Barhanin J, Faure S, Gary F, Coumel P, Petit C, Schwartz K, Guicheney P. A novel mutation in the potassium channel gene KVLQT1 causes the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen cardioauditory syndrome. Nat Genet 15: 186–189, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nilsson SE. Ultrastructural organization of the retinal pigment epithelium of the Cynomolgus monkey. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 56: 883–901, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peroz D, Dahimene S, Baro I, Loussouarn G, Merot J. LQT1-associated mutations increase KCNQ1 proteasomal degradation independently of Derlin-1. J Biol Chem 284: 5250–5256, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Robbins J. KCNQ potassium channels: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Ther 90: 1–19, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schroeder BC, Hechenberger M, Weinreich F, Kubisch C, Jentsch TJ. KCNQ5, a novel potassium channel broadly expressed in brain, mediates M-type currents. J Biol Chem 275: 24089–24095, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schroeder BC, Waldegger S, Fehr S, Bleich M, Warth R, Greger R, Jentsch TJ. A constitutively open potassium channel formed by KCNQ1 and KCNE3. Nature 403: 196–199, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Singh NA, Charlier C, Stauffer D, DuPont BR, Leach RJ, Melis R, Ronen GM, Bjerre I, Quattlebaum T, Murphy JV, McHarg ML, Gagnon D, Rosales TO, Peiffer A, Anderson VE, Leppert M. A novel potassium channel gene, KCNQ2, is mutated in an inherited epilepsy of newborns. Nat Genet 18: 25–29, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stohr H, Stojic J, Weber BH. Cellular localization of the MPP4 protein in the mammalian retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 5067–5074, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takahira M, Hughes BA. Isolated bovine retinal pigment epithelial cells express delayed rectifier type and M-type K+ currents. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 273: C790–C803, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tinel N, Diochot S, Borsotto M, Lazdunski M, Barhanin J. KCNE2 confers background current characteristics to the cardiac KCNQ1 potassium channel. EMBO J 19: 6326–6330, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Trumble WR, Sutko JL, Reeves JP. ATP-dependent calcium transport in cardiac sarcolemmal membrane vesicles. Life Sci 27: 207–214, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang Q, Curran ME, Splawski I, Burn TC, Millholland JM, VanRaay TJ, Shen J, Timothy KW, Vincent GM, de Jager T, Schwartz PJ, Toubin JA, Moss AJ, Atkinson DL, Landes GM, Connors TD, Keating MT. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene: KVLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias. Nat Genet 12: 17–23, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wen R, Lui GM, Steinberg RH. Whole-cell K+ currents in fresh and cultured cells of the human and monkey retinal pigment epithelium. J Physiol 465: 121–147, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu T, Nie L, Zhang Y, Mo J, Feng W, Wei D, Petrov E, Calisto LE, Kachar B, Beisel KW, Vazquez AE, Yamoah EN. Roles of alternative splicing in the functional properties of inner ear-specific KCNQ4 channels. J Biol Chem 282: 23899–23909, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yagi T, Macleish PR. Ionic conductances of monkey solitary cone inner segments. J Neurophysiol 71: 656–665, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang D, Pan A, Swaminathan A, Kumar G, Hughes BA. Expression and localization of the inwardly rectifying potassium channel Kir7.1 in native bovine retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 3178–3185, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yang D, Swaminathan A, Zhang X, Hughes BA. Expression of Kir7.1 and a novel Kir7.1 splice variant in native human retinal pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res 86: 81–91, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang D, Zhang X, Hughes BA. Expression of inwardly rectifying potassium channel subunits in native human retinal pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res 87: 176–183, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yeung SY, Lange W, Schwake M, Greenwood IA. Expression profile and characterisation of a truncated KCNQ5 splice variant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 371: 741–746, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang XM, Kimura Y, Inui M. Effects of phospholipids on the oligomeric state of phospholamban of the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Circ J 69: 1116–1123, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]