Abstract

The discovery that cells in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract express the same molecular receptors and intracellular signaling components known to be involved in taste has generated great interest in potential functions of such post-oral “taste” receptors in the control of food intake. To determine whether taste cues in the GI tract are detected and can directly influence behavior, the present study used a microbehavioral analysis of intake, in which rats drank from lickometers that were programmed to simultaneously deliver a brief yoked infusion of a taste stimulus to the intestines. Specifically, in daily 30-min sessions, thirsty rats with indwelling intraduodenal catheters were trained to drink hypotonic (0.12 M) sodium chloride (NaCl) and simultaneously self-infuse a 0.12 M NaCl solution. Once trained, in a subsequent series of intestinal taste probe trials, rats reduced licking during a 6-min infusion period, when a bitter stimulus denatonium benzoate (DB; 10 mM) was added to the NaCl vehicle for infusion, apparently conditioning a mild taste aversion. Presentation of the DB in isomolar lithium chloride (LiCl) for intestinal infusions accelerated the development of the response across trials and strengthened the temporal resolution of the early licking suppression in response to the arrival of the DB in the intestine. In an experiment to evaluate whether CCK is involved as a paracrine signal in transducing the intestinal taste of DB, the CCK-1R antagonist devazepide partially blocked the response to intestinal DB. In contrast to their ability to detect and avoid the bitter taste in the intestine, rats did not modify their licking to saccharin intraduodenal probe infusions. The intestinal taste aversion paradigm developed here provides a sensitive and effective protocol for evaluating which tastants—and concentrations of tastants—in the lumen of the gut can control ingestion.

Keywords: chemoreceptor, gastrointestinal, denatonium benzoate, food learning, cholecystokinin

chemoreceptors are indispensable to the control of food intake. As taste receptors on the tongue and in the oral cavity, they supply signals critical for accepting and rejecting foods for consumption, promoting intake of palatable foods, and preparing the digestive system for the arrival of nutrients. Complementary to this early oral sensory processing, chemoreceptors in the stomach and intestines transduce signals from the lumen to adjust motility, secrete digestive enzymes, and initiate satiation (cf., 24). Accordingly, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract has been conventionally considered to have a more or less continuous sensory surface for tracking meals to engage and revise apposite and coordinated responses particular to the properties of the food and the body's physiological state. Despite this arrangement, relatively little work has been done to compare the encoding processes of oral taste receptors with those of the chemoreceptors situated in the post-oral GI tract.

Recently, however, the discovery of taste-like receptors in the GI tract, like members of the T1R (sweet) and T2R (bitter) receptor families, as well as their taste-specific intracellular signaling components (e.g., α-gustducin and TRPM-5) (4, 5, 14, 20, 22, 23, 26, 30, 46, 50) has revealed some parallels among oral and post-oral chemoreceptors and has generated interest in the functional relevance of “taste” receptors in the gut. Such interest has only been reinforced by the mounting evidence that post-oral satiety signals are disrupted in obesity (e.g., 9, 10, 12, 13). While the anatomical and molecular correspondences have accordingly inspired a rethinking of how chemicals are detected and encoded by post-oral chemoreceptors to affect physiological, and possibly behavioral, controls of intake, these speculations have outpaced experimental analysis.

At least one key complicating factor has commonly impeded investigations of the functional aspects of gut taste. When nutrients are ingested or infused, the specific contributions of the preabsorptive chemoreceptors in the gut are generally confounded with the later postabsorptive consequences, with respect to both within-meal feedback and the longer-term development of food preferences. Complicating this problem, in many cases, it has also been customary or even necessary to deliver a large stimulus infusion over a prolonged period of time (e.g., 30 min to several hours) to demonstrate overt effects on behavior, but given that almost as soon as the stimulus arrives in the gut, it is transformed and transported, at varying rates dependent, in part, on the properties of the compound, the stimulus is likely permitted to engage both preabsorptive and postabsorptive pathways during that period. Indeed, feedback from both these sources are accessed and incorporated into ingestive behavior. For example, rats readily establish a conditioned flavor preference (CFP) for an oral flavor that has been repeatedly paired with GI nutrient infusions (1, 40, 41, 53). This CFP develops even when vagal and/or splanchnic afferents are surgically or chemically disrupted, suggesting nutrients sufficiently engage postabsorptive signals to affect behavior (40, 53). At the same time, vagal deafferentation abolishes rapid discrimination of GI stimulus properties for CFP (53) and attenuates the short-term satiating effects of some, but not all, nutrients in the GI tract, suggesting auxiliary information is relayed by preabsorptive receptors (40, 49).

In addition to illustrating that both preabsorptive and postabsorptive signaling pathways are involved in the postingestive controls of intake, the CFP example highlights yet another consideration with implications for behavioral analyses of GI infusions. Test subjects appear to be quite flexible with respect to selecting different sources of feedback to solve the task. That is, when limited by surgical or chemical intervention to use postabsorptive information to associate a flavor with its postingestive outcomes, rats seem to accordingly attend to those features of the stimulus and make appropriate changes in behavior. Consistent with this observation, intact test subjects may be forced to preferentially use one set of cues (e.g., preabsorptive signals from the intestinal receptors) by simply arranging the demands of the behavioral task to render those (preabsorptive) cues most informative to response decisions (see Ref. 33 for a review).

Thus, in light of such experimental issues, the purpose of the present set of experiments was to develop a microbehavioral paradigm to more directly study the stimulus encoding and functional consequences of GI chemoreception. In a modified conditioned taste aversion preparation, rats were forced to use early “taste” cues arising from the intestines to control ongoing ingestive behavior. More specifically, to attempt to assess preabsorptive sensory events, the protocol was designed to 1) probe intestinal chemoreceptive responses to noncaloric, nonreadily absorbable tastants presented in simple hypotonic salt solutions, 2) measure short latency responses to tastants as they reach the intestines, thus presumably monitoring events that occur prior to extensive processing of the stimulus within the gut, 3) limit the duration of the taste infusion period within a longer session, to track lick response recovery after the stimulus terminates and, thus, in conjunction with a discrete onset, potentially indicating a “stimulus-bound” response, 4) render oral cues noninformative, which when combined with the early brief infusion period, forces rats to use those early taste cues arising from the intestine to solve the task, and 5) use an associative approach, that is, a modified conditioned taste aversion, to amplify responses to weak or innocuous intestinal stimuli, without the need to increase infusion volumes or prolong infusion periods. This procedure was developed with a representative bitter taste agonist, denatonium benzoate (DB), and was then expanded to examine a representative sweet taste agonist, saccharin (Sacc).

METHODS

Subjects.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were individually housed in hanging-wire mesh cages in a climate-controlled colony room on a 12:12-h light-dark schedule (lights on at 0600). Experiments were conducted in the light phase. Rats were fed ad libitum powdered chow (Purina #5001) and tap water during a 1-wk acclimation period and in a postsurgery recovery period, before being switched to a restricted food and water access schedule for the remainder of the experiment (see Deprivation schedule). All animal care, surgical, and experimental procedures were approved by the Purdue University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgery.

Following acclimation to the colony room (1 wk), rats were fasted overnight for surgery and then anesthetized with Nembutal (pentobarbital sodium; 60 mg/kg ip) and laparotomized for implantation of an intraduodenal catheter. First, a puncture wound was made in the greater curvature of the forestomach, and a Silastic catheter (ID = 0.64 mm, OD = 1.19 mm; Dow Corning, Midland, MI) was advanced through the stomach and pyloric sphincter. The end of the catheter was tethered to the intestinal wall ∼4 cm distal to the pylorus with a piece of Marlex mesh and a single-stay suture. Then, the puncture wound in the forestomach was closed around the catheter with a pursestring suture and a serosal tunnel. The free end of the catheter was tunneled subcutaneously to an interscapular exit site, where it was exteriorized for connection to a Luer Lok adapter, which was mounted in a harness worn by the rat (Quick Connect Harness, Strategic Applications, Libertyville, IL). Rats were treated with postoperative analgesic and antibiotic.

Apparatus.

Daily sessions were conducted in nine identical operant chambers that were each equipped with a controlled access lickometer and infusion line (Habitest, Coulbourn Instruments, White Hall, PA). The lickometer comprised a sipper spout that was located in a recessed magazine in the center of the endwall, ∼2 cm above the grid floor, and a photobeam that was mounted at the base of the sipper spout to record licks. Each lick was counted and programmed (Graphic State, ver. 3.03) to operate a pump to deliver 5 μl of 0.12 M sodium chloride (NaCl) solution to the sipper spout via a polyethylene connection tube. This 5 μl/lick delivery rate approximated a 1 ml/min consumption rate. Rats had access to the active sipper spout for the entire 30-min session. Throughout all experimental sessions (as described below), 0.12 M NaCl was the only solution delivered to the sipper spout for oral consumption.

In the final phase of pretraining and then for the remainder of the experiment (see below), a brief intraduodenal infusion was added. During the first 6 min of the drinking session, each lick also operated a second pump and syringe connected to the intraduodenal infusion line. The line consisted of polyethylene tubing to a single channel swivel (Instech Solomon, Plymouth Meeting, PA), which was joined to a polyethylene tube encased in a spring tether; this arrangement permitted the rat to move freely about the chamber. Prior to the start of the session, the free end of the spring tether was fastened to the Luer Lok on the rat's harness to establish connection with the indwelling intraduodenal catheter. Direct delivery of the intraduodenal infusate (5 μl/lick) was yoked to active licking at the sipper spout. Importantly, these yoked infusions were only available for the first 6 min of the session; once this period elapsed, the intraduodenal infusion pump was rendered inactive for the remainder of the 30 min. The intraduodenal infusate consisted of either a 0.12 M NaCl or isomolar lithium chloride (LiCl) vehicle alone, or with a taste stimulus added, depending on the session type. Prior to each session, the infusion lines were thoroughly flushed with 0.12 M NaCl to rinse out any remnants of the previous session's infusate from the line. The dead space in the line was filled with 0.12 M NaCl (∼0.40 ml), and then the line was attached to the syringe containing the intraduodenal stimulus; this prevented the rats from being exposed to the intraduodenal stimulus, as they were connected to the infusion line. Additionally, at the conclusion of the daily session, the intraduodenal catheter was flushed with 2 ml of isotonic saline and capped.

Stimuli and drugs.

Stimulus properties are shown in Table 1. On all training and test sessions, the rats licked for NaCl, while being infused with NaCl or LiCl. LiCl was mixed to achieve the approximate final per session dosage of 8 mg, while matching the molarity of the NaCl. For example, since rats self-infused 5 ml of intraduodenal NaCl in pretraining, then 0.12 M LiCl (e.g., 160 mg LiCl in 31.5 ml deionized water) was diluted with 0.12 NaCl (e.g., 480 mg NaCl in 68.5 ml deinonized water) for a final LiCl concentration of 1.6 mg/ml. LiCl was delivered at this low dose (8 mg) to prevent rats from shutting down intake altogether, following the first exposure to LiCl and to keep rats drinking at a relatively high and stable rate day to day. Denatonium benzoate (DB; 10 mM) or sodium saccharin (Sacc; 9.75 mM) were added to either the intraduodenal NaCl or LiCl, depending on group assignment (see Experiments). All reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All solutions were prepared fresh each day with deionized water and delivered at room temperature. Devazepide (DEV; Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK), a CCK-1R antagonist, was prepared by first dissolving 10 mg in 0.1 ml of DMSO, then adding 0.1 ml of Tween-80, followed by 0.8 ml of isotonic saline. This 10 mg/ml solution was then diluted to 75 μg/ml by adding isotonic saline, aliquoted in 1-ml vials, and frozen at −20°C. Just prior to administration, DEV was thawed and sonicated. Equivalent volumes of the DMSO, Tween-80, and saline were mixed and stored for use as the vehicle control (VEH).

Table 1.

Properties of the oral solution and intestinal infusates

| Concentration | pH | mOsm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Solution | |||

| All experiments | |||

| NaCl | 0.12 M | 6.05 | 219 |

| Intestinal Infusates | |||

| Experiment 1 | |||

| LiCl | 31.5% 0.12 M LiCl +68.5% 0.12 M NaCl | 5.94 | 215 |

| DB in NaCl | 10 mM DB in 0.12 M NaCl | 6.72 | 246 |

| Experiment 2 | |||

| NaCl | 0.12 M | 6.05 | 219 |

| LiCl | 31.5% 0.12 M LiCl +68.5% 0.12 M NaCl | 5.94 | 215 |

| DB in LiCl | 10 mM DB in 31.5% 0.12 M LiCl +68.5% 0.12 M NaCl | 6.63 | 249 |

| Experiment 3 | |||

| LiCl | 35% 0.12 M LiCl +65% 0.12 M NaCl | 6.02 | 215 |

| DB in NaCl | 10 mM DB in 0.12 M NaCl | 6.72 | 246 |

| Sacc in NaCl | 9.75 mM sodium saccharin in 0.12 M NaCl | 6.89 | 246 |

| Sacc in LiCl | 9.75 mM sodium saccharin in 35% 0.12 M LiCl +65% 0.12 M NaCl | 6.25 | 235 |

| Experiments 4 and 5 | |||

| DB in NaCl | 10 mM DB in 0.12 M NaCl | 6.72 | 246 |

| Sacc in NaCl | 9.75 mM sodium saccharin in 0.12 M NaCl | 6.89 | 246 |

Note: The LiCl: NaCl concentration ratio in experiment 3 was adjusted to account for the lower intake and infusion volume level in that cohort of rats. The final target dose of LiCl was still 8 mg. DB, denatonium benzoate; Sacc, saccharin.

Deprivation schedule.

Upon recovery from surgery (∼2 wk), rats were gradually accustomed to a water deprivation routine in the home cage; ultimately, on this schedule, rats were given one 30-min drinking session per day (at the same time each day), followed ∼30 min later by access to powdered chow and a 10-ml supplement of deionized water for 5 h. In addition to motivating animals to drink the majority of their daily fluid in a 30-min period, this schedule minimized the amount of food and water in the stomach and intestines during the drinking session (by ∼18 h deprivation), while still permitting the rats to gain ∼2 g of body wt per day. After the initial acclimation to the schedule and for the remainder of the experiment, rats were transferred to a lickometer chamber for the daily 30-min drinking session.

Pretraining.

Rats were pretrained to drink at the sipper spout for 0.12 M NaCl for 30 min for 6 days (no intraduodenal infusions were made during these initial sessions). This was followed by 8 days, in which rats were allowed to drink from the spout for NaCl (for 30 min) and an intraduodenal infusion of 0.12 M NaCl was yoked to licking in the first 6 min only of each session to establish extensive oral and intestinal experience with the safe salt solution.

Probe training.

At the conclusion of pretraining (within experiments 2 and 3), two-day average (last 2 days of pretraining) body weight, lick rate, total licks in the first 6 min, and total licks over the entire 30 min were calculated for each rat; then, rats were assigned to groups matched on the means ± SD on each of these four factors for probe training. Each probe trial consisted of two sessions, which were run on consecutive days (presented in a counterbalanced order across training) and differed only on the type of intraduodenal infusate that was delivered; otherwise, these sessions were run in an identical manner as the latter phase of pretraining. In general, for each trial, rats received an intraduodenal 0.12 M NaCl infusion on one probe session and an intraduodenal 0.12 M LiCl infusion on the alternate probe session (but note one exception in experiment 3 below). For some experiments, taste stimuli were added to one or both of these infusates (see Experiments for descriptions of specific pairings). One to three baseline restabilization sessions, in which rats licked for NaCl and were infused with NaCl vehicle (no probe tastants added), were interposed between each two session probe trial. Restabilization sessions were identical to those described for the latter part of pretraining.

Statistical analyses.

All analyses were conducted with Statistica (v10; Statsoft, Tulsa, OK), and data were plotted with GraphPad (Prism 5; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). For all comparisons, an initial trial by probe infusate by minute (experiments 1 and 2) or trial by group by minute (experiment 3) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted. Then, to break down significant main effects and interactions, separate repeated-measures ANOVAs or post hoc Newman-Keuls tests were run. Because intake was reliably the highest at minute 2 on all infusate session types and for all groups, the difference in lick rate between the two probe sessions across the next 6 min (minutes 3–8) was calculated at each trial for each group in experiments 1 and 2 to examine the development of the early response across training. Additionally, following analyses that compared lick patterns between the two probe infusate session types, separate repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted on each probe infusion session across trials to determine changes in response to the particular probe over repeated exposure. An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: rats rapidly suppress ongoing intake in response to bitter DB in the intestine.

The GI mucosa is the final barrier between the internal and external milieus, where preventing toxins from entering circulation is as important as digesting and absorbing nutrients. Although the latter functions have been the primary focus of GI chemoreceptor research to date, the presence of bitter (T2R) receptors in the postoral GI tract is consistent with a role for chemoreceptors in defensive GI functions as well (45). In the gustatory taste system, bitter taste receptors are wired to rejection responses to limit the ingestion of noxious foods (25), but, in the event that these foods are ingested, GI T2Rs may provide a second line of defense. Indeed, application of the bitter compound DB directly to GI cells stimulates the release of CCK and slows gastric emptying (8, 17, 18). In addition to initiating these local reflexes, GI DB conditions avoidance of an oral flavor with which it has been repeatedly paired (17, 19), suggesting 1) that the stimulus has aversive properties in the GI tract and 2) that these signals are integrated centrally, such that the rat avoids the associated flavor upon subsequent opportunities to consume that same flavor. Still, it is unclear whether the bitter stimulus engages a preabsorptive chemoreceptor pathway to affect motility and intake. In fact, in an experiment with some similarities to the present experiments, Glendinning et al. (17) suggested that the underlying signal was of a humoral basis, because rats did not suppress intake until ∼6 min after the start of the yoked gastric DB infusions and maintained this suppression for an extended period of time. However, because these gastric DB infusions in the experiment of Glendinning et al. were continuously yoked to intake across the 30-min sessions, the persistent suppression could reflect repeated preabsorptive stimulation of the bitter receptors, in addition to, or even separate from, a humoral response. It remains unclear then whether DB is aversive because of its bitter taste properties in the GI tract or some other delayed aversive side effect produced by the compound (e.g., malaise).

Thus, in the procedure developed here, thirsty rats licked at a spout for a safe 0.12 M NaCl solution for 30-min sessions each day, while receiving a brief (6 min) yoked intraduodenal infusion of the same salt solution. On probe sessions, the intraduodenal infusate contained either 0.12 M NaCl or was replaced with an isomolar LiCl solution. Since at isomolar concentrations, NaCl and LiCl have common early sensory properties (e.g., salt taste), but very different unconditioned effects (i.e., LiCl is a malaise-inducing toxic agent) (38), these two salts were ideal candidates for establishing a task in which rats could not use oral cues at the sipper spout (because that solution was always salty plain NaCl) and presumably could not likewise use the early sensory properties of the two infusion vehicles to determine when they would receive an aversive stimulus (i.e., LiCl), unless a specific aversive taste cue (i.e., DB) was added into one of the intraduodenal infusion vehicles (e.g., NaCl). Intraduodenal infusions were yoked to drinking for the first 6 min only of the 30-min drinking session, because 1) voluntary intake is greatest and steadiest in the early part of the daily drinking session—this ensured that the rats self-administered a significant infusion volume at a relatively stable rate, 2) by keeping the infusion to the first 6 min, rats were forced to use immediate “taste” cues to detect the intraduodenal stimulus, rather than delayed the effects of the stimulus, and 3) the voluntary intake conditions permitted the rats to control the amount of infusion they received, so that if rats learned to predict the later aversive consequences from the early sensory cues (over the course of five exposures), then they could escape or minimize those consequences by discontinuing intake during the infusion period.

In Experiment 1, DB was added as the intestinal taste cue to the intraduodenal NaCl infusate on one set of probe sessions, while the intraduodenal LiCl infusate was left unadulterated on the interposed, alternative set of probe sessions. While both intraduodenal probe stimuli used here (DB and LiCl) are known to be aversive, they are also believed to engage different postingestive pathways. In particular, because LiCl acts primarily by a postabsorptive route to its targets in the central nervous system (e.g., area postrema) to produce aversive consequences (32, 33) and was delivered so as to be difficult to discern on the basis of early sensory properties from safe NaCl (38), it was expected that rats would inhibit intake in the final minutes only of the LiCl probe sessions, reflecting the onset of the malaise. On the other hand, assuming DB activates bitter taste receptors in the GI tract, it was predicted that rats would rapidly curb intake in response to the arrival of the bitter stimulus in the intestine. Rats received five sessions with each of these aversive probes to examine the development of the response over several trials.

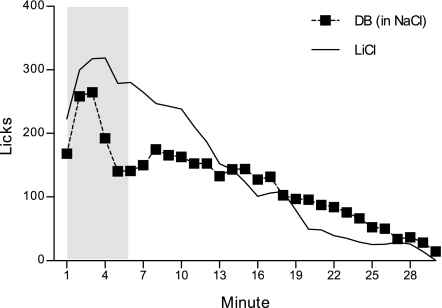

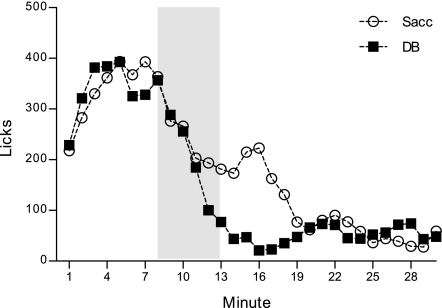

Mean licks/min on DB in NaCl and LiCl probe sessions, collapsed across five trials, are presented in Fig. 1. Overall, ANOVA yielded a significant probe infusate by minute interaction, F(29, 174) = 6.58, P = 0.00001. Post hoc comparisons indicated that this was due to a lick rate reduction during minutes 4–10 of the DB in NaCl session, relative to the alternative LiCl session (largest P = 0.03 at minute 8). This lick rate reduction was transient enough so as not to significantly affect total intake over the entire 30-min session (DB in NaCl: 121.00 ± 30.13 licks/min, LiCl: 141.52 ± 23.80 licks/min), F(1, 6) = 2.51, P = 0.16. The early transient lick rate suppression in response to the arrival of DB developed with repeated probe trials, F(116, 696) = 1.43, P = 0.004. Rats did not discriminate among the two probe infusate types on trials 1–3 (smallest P = 0.13 on trial 3). On trial 4, rats began to significantly curb licking in response to the arrival of DB in the intestine (minutes 7 and 9, P = 0.02 and 0.03, respectively), F(29, 174) = 3.37, P = 0.00001. The response was more rapid and robust (minutes 4–6, largest P = 0.03 at minute 4) on the fifth and final trial of probe training, F(29, 174) = 5.22, P = 0.00001. A separate analysis conducted on the DB in NaCl probe session across the five trials confirmed this emergence of the response to DB in the later trials, F(116, 696) = 2.00, P = 0.00001. The same analysis was likewise conducted on the plain unadulterated LiCl probe sessions across five trials and further indicated that the response to LiCl infusions did not change from the first exposure to the last, F(116, 696) = 0.91, P = 0.74.

Fig. 1.

Mean licks per minute for a NaCl solution at the sipper spout collapsed across five 30-min probe trials. A brief (6 min) intraduodenal infusion was yoked to licking at the beginning of the 30-min session (shaded in gray). Denatonium benzoate (DB; 10 mM) in NaCl was infused for one session in each trial, and plain unadulterated LiCl was infused for the alternative session in each trial (n = 7).

These results demonstrated that rats were able to detect the immediate stimulus properties of bitter DB applied directly to the intestine to transiently curb ongoing intake. Detection of DB was quite rapid (within 2 or 3 minutes of the start of session). Interestingly, however, this response did not appear until the fourth exposure to the DB infusion. Prior to the emergence of this early lick rate suppression in the fourth trial, intake remained steady across the first half of the session, before gradually decaying and then completely shutting down in the final minutes of the session. This pattern of results could reflect a couple of different underlying mechanisms. For one, mere repeated exposure to the bitter tasting stimulus in the intestine may have resulted in sensitization of the response. Alternatively, it may be that DB produced a delayed onset-aversive stimulus (e.g., malaise) in the intestine, independent of its taste properties, and with repeated exposure, rats associated the early sensory properties of the compound with those consequent events, forming an intestinal taste aversion. In other words, the aversive consequence of the DB stimulus may have reinforced the detection of the early intestinal taste cues of DB, which, in later trials, permitted rats to curb intake more immediately in response to the arrival of the stimulus, minimizing further insult. Rats were not able to use the early sensory properties of LiCl, which were arranged to be indiscriminable from those of NaCl in the intestine, in this same fashion to anticipate impending malaise, consistent with the previous findings of Rusiniak et al. (38).

Experiment 2: taste aversion in the intestine: intraduodenal DB in LiCl increases the strength and temporal resolution of the response.

One possible explanation of the development of the response to intraduodenal DB across trials observed in experiment 1 is that rats formed a taste aversion to the bitter stimulus in the intestine, following extensive experience with the aversive compound. Since the unconditioned malaise associated with LiCl has been more fully characterized and since, in experiment 1, the late-session depression of drinking was clearer for LiCl than for DB in NaCl, experiment 2 was designed to more directly test the intestinal taste aversion explanation. That is, the purpose of experiment 2 was to determine whether intestinal DB paired with LiCl strengthened the response to the early taste properties of the bitter compound. One group of rats received extensive experience with licking for, and being infused with, NaCl, before receiving bitter intraduodenal DB in 0.12 M LiCl as the probe infusate on five sessions. To extend our observations on LiCl, a second group of rats received unadulterated intraduodenal LiCl on the same five sessions. Plain intraduodenal NaCl was the comparison probe infusate for both groups. All other licking and infusion parameters were the same as those described for experiment 1 (see methods).

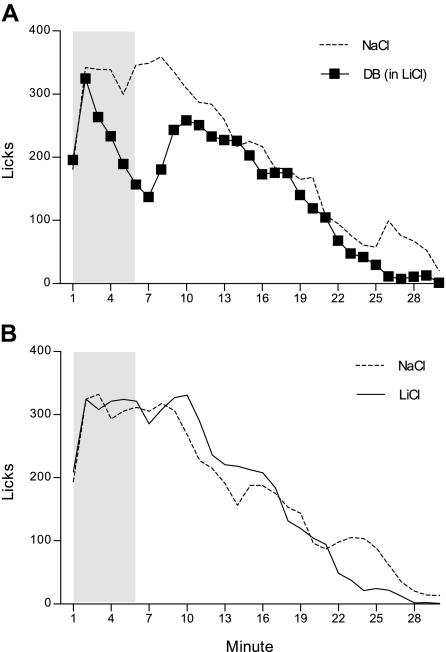

Figure 2A presents mean licks/minute on plain NaCl and DB in LiCl probe sessions, collapsed across the five trials. Overall, rats consumed significantly less on the DB in LiCl infusion sessions (148.01 ± 25.81 licks/min), compared with the plain NaCl infusion sessions (203.27 ± 15.51 licks/min), F(1, 6) = 11.85, P = 0.01. This was due to a transient, but robust, reduction in licking during minutes 6–8 (largest P = 0.0002 at minute 8), F(29, 174) = 2.56, P = 0.0001. Although this did not further vary as a function of trial, F(166, 696) = 1.18, P = 0.11, because it was expected on the basis of experiment 1 that rats would develop the response to intraduodenal DB across training, each trial was subsequently analyzed. Rats did not discriminate among the two probe infusates on trial 1, F(29, 174) = 0.76, P = 0.80. However, by trial 2, a significant suppression in drinking in response to the arrival of DB to the intestine emerged (minute 7, P = 0.007), F(29, 174) = 1.71, P = 0.02. This pattern continued to develop over trials 3 and 4 (largest P = 0.02 for main effect of probe infusate at trial 3). By the fifth and final probe trial, rats rapidly suppressed licking by minute 3, completely stopped drinking at minute 6 (P = 0.04), and resumed normal intake (to intraduodenal NaCl levels) by minute 9, F(29, 174) = 1.84, P = 0.009. A separate analysis on the DB in LiCl probe sessions across trials further confirmed the rapid development of the early transient response to the arrival of DB in the intestine across trials, F(116, 696) = 1.31, P = 0.02. Although the separate analyses on the plain NaCl infusion probes across trials likewise yielded a significant trial by minute interaction, F(116, 696) = 1.35, P = 0.01, subsequent inspection did not reveal any systematic changes across training for this infusate probe.

Fig. 2.

Mean licks per minute for a NaCl solution at the sipper spout collapsed across five 30-min probe trials. A brief (6 min) intraduodenal infusion was yoked to licking at the beginning of the 30-min session (shaded in gray). One group of rats (n = 7) received 10 mM of DB mixed into LiCl infusions for one session per trial and received plain NaCl infusions for the alternative session per trial (A). A second group of rats (n = 6) received plain LiCl infusions for one session in each trial and plain NaCl infusions for the alternative session in each trial (B).

Figure 2B presents the mean licks/minute across plain NaCl and plain LiCl intraduodenal probe sessions for the second group for which no cues or tastants were added to the infusates, collapsed across five trials. Overall, rats consumed comparable amounts on the two probe sessions (NaCl: 177.12 ± 34.07, LiCl: 174.90 ± 25.57 licks/min), F(1, 5) = 0.03, P = 0.86. This group did not discriminate among the two infusates during the early minutes of the session, with the exception of a momentary dip at minute 11 (P = 0.05), where responding on the intraduodenal NaCl session fell below that of the intraduodenal LiCl session; otherwise, these rats exhibited only a late-session reduction in drinking, following the LiCl infusion (minute 24, P = 0.02), F(29, 145) = 2.59, P = 0.0001. Even though ANOVA did not return a significant main effect or interaction involving trial (smallest P = 0.53 for main effect), separate analyses were still conducted on each probe type across training to further determine whether lick patterns in response to the two probe infusates changed with repeated exposure. Indeed, intake patterns did not change in response to either intraduodenal LiCl or intraduodenal NaCl probes with repeated training, F(116, 580) = 0.91, P = 0.72 and F(116, 580) = 0.86, P = 0.85, respectively. Since it was possible that rats in experiment 1, who received DB in NaCl and unadulterated LiCl in separate, but consecutive sessions, only failed to detect the early cue properties of LiCl because they were attending more to the (more salient) DB stimulus sessions, we sought to take the competing stimulus out of the equation in this group by presenting these rats with only unadulterated intraduodenal LiCl and NaCl infusions; the results obtained from this group further indicated that rats were unable to discern an early LiCl taste to control ingestion in this task.

Because it was predicted that LiCl would strengthen taste aversion learning to intraduodenal DB, we compared the difference in licking in the early minutes of the session (minutes 3–8) on the two probe session types across trials for three groups (see Fig. 3). Whereas the response to DB emerged gradually across probe training for the rats that received DB in NaCl infusions (from experiment 1), F(4, 24) = 2.36, P = 0.08, LiCl added to the DB infusate accelerated the emergence of the early response (by trial 2 for DB in LiCl group from experiment 2, P = 0.005), F(4, 24) = 5.18, P = 0.004. Rats that received plain intraduodenal LiCl, opposite plain intraduodenal NaCl (from experiment 2), did not alter licking in the early infusion period across trials, F(4, 20) = 0.35, P = 0.84.

Fig. 3.

Means ± SE difference in licks per minute in minutes 3–8 on the two probe sessions at each trial as a function of training group. For one group of rats (from experiment 1), the difference between licking for NaCl on intraduodenal DB in NaCl sessions from the alternate plain intraduodonal LiCl sessions is plotted (DB in NaCl). For a second group of rats (from experiment 2), the difference between licking for DB in LiCl sessions from the alternate plain NaCl sessions is plotted (DB in LiCl). For a third group (from experiment 2), the difference between licking for plain LiCl sessions from the alternate plain NaCl sessions is plotted (LiCl).

Although the results from the group that received plain intraduodenal LiCl and NaCl on alternate sessions strongly suggest that rats do not readily discriminate intestinal LiCl on the basis of early taste properties of the solution, it remained possible that the enhanced detection of intraduodenal DB when it was presented in LiCl (as compared with DB in NaCl in experiment 1) was due to some interaction among the two stimulus elements of the particular infusate, whereby, for instance, the sensory properties of LiCl acted to enhance the sensory properties of DB or the DB stimulus potentiated the detection of the early sensory properties of LiCl. Therefore, in a post probe training test, intraduodenal DB was delivered in NaCl instead of LiCl for the group of rats that were previously trained with DB in LiCl. Even when DB was transferred into an intraduodenal NaCl vehicle, overall intake remained significantly reduced (140.72 ± 34.47 licks/min), relative to that on the plain intraduodenal NaCl infusion test (227.47 ± 22.61 licks/min), F(1, 6) = 6.49, P = 0.04. Consistent with the lick rate pattern observed during training, rats rapidly inhibited intake in response to DB in NaCl in the intestine (P = 0.03 at minute 10) and resumed normal intake shortly thereafter, F(29, 174) = 1.56, P = 0.04. These results suggest that LiCl did not act as an intestinal DB taste enhancer, but rather merely functioned as a reinforcing stimulus to establish a robust response to the intestinal taste of DB. Furthermore, when DB was removed from LiCl in a separate post probe training test, these same rats failed to discriminate a plain LiCl infusion from a plain NaCl infusion, F(29, 174) = 1.24, P = 0.20, suggesting that DB did not enhance detection of Li taste.

The results from this experiment confirm those of our previous experiment in showing that DB is rapidly detected in the intestine. In addition, we replicated our previous effect with plain intraduodenal LiCl in a separate group; intake ceased ∼20 min after the LiCl infusion, most likely due to the onset of the adverse unconditioned GI symptoms, but rats were otherwise not able to learn to use the early sensory features of the intraduodenal LiCl stimulus to control intake. On the other hand, intraduodenal LiCl did augment the development of a response to another tastant, DB, and strengthened the temporal contiguity between the stimulus and response. Thus, interestingly, it appears that rats learn taste aversions to an intestinal taste stimulus, such that those early stimuli in the intestine associate with subsequent events (e.g., malaise) and accordingly modify ingestive behavior upon reexposures to those same cues in the intestine.

Experiment 3: rats do not develop a taste aversion to saccharin in the intestine.

Despite the presence of sweet taste receptors (T1Rs) in the intestine (14) and the capacity for nonmetabolizable/nonabsorbable artificial sweeteners (e.g., saccharin) to stimulate incretin (e.g., GLP-1) release and upregulate glucose transport (23, 26, 30, 31, 44), other studies have failed to demonstrate a role for GI nonnutritive sweet taste in the behavioral control of intake. For instance, one study showed that rats did not suppress intake following a preload of sweetener to the stomach (51), while a separate study showed that rats did not develop a preference to a flavor that had been repeatedly paired with GI sweetener infusions (41). Both of these behavioral measures are, however, sensitive to sweet-tasting caloric substances, like glucose (1, 40, 41, 49, 51). Because artificial sweeteners presumably only provide a sweet taste signal (i.e., no calories) in the intestine, it is possible that the typical longer-term behavioral parameters used in preload and flavor preference studies are not well suited to look at rapid intestinal taste per se, in the absence of caloric stimuli. Thus, the temporal resolution offered by the current preparation might reveal detection of an artificial sweetener, like Sacc, by examining its immediate effects on ongoing intake. Moreover, it is possible that because artificial sweeteners have relatively few postingestive effects, the stimulus is simply too weak or lacking in salience when presented alone; pairing the sweet stimulus with a strong postingestive event (LiCl) (that lacks any confounding caloric effects) might enhance the detection of a weak Sacc stimulus in the intestine, as was observed for DB in the previous experiment.

Thus, three groups of rats were compared here. As described previously, all groups always licked only for the safe NaCl at the sipper spout, but were infused on discrete probe sessions with different infusates, depending on group assignment. One group received intraduodenal Sacc in NaCl, while another group received intraduodenal Sacc in LiCl and yet a third group of rats received plain unadulterated LiCl. Since the previous experiments showed robust and consistent lick suppression to intraduodenal DB that developed over several trials, all three groups received intraduodenal DB (in NaCl) on their alternate probe sessions for comparison. Thus, the first group provided a baseline discrimination between the sweet Sacc and bitter DB in the intestine. Sacc was delivered in LiCl for the second group to establish an intestinal taste aversion to the sweet stimulus. But, in the event that the second group appeared to show detection only after pairings with LiCl, and since the previous experiments indicated that rats do not respond to the early stimulus features of LiCl alone, we included a third group that received unadulterated intraduodenal LiCl probes to verify that LiCl reinforced earlier detection of Sacc (in LiCl) relative to plain intraduodenal LiCl. In the event that rats in the second group do not detect Sacc, then their response to intraduodenal Sacc in LiCl should look as though they received plain LiCl as well.

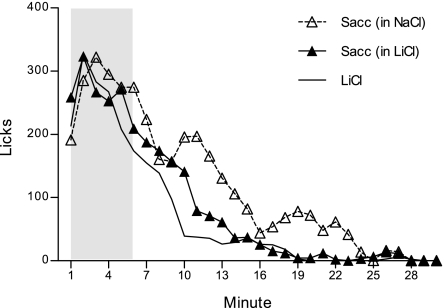

Figure 4 shows the licks/min response on intraduodenal Sacc or LiCl probe sessions, collapsed across 6 trials, for each group. An overall ANOVA comparing the licks per minute across the six 30-min intraduodenal Sacc probe trials yielded a significant group by minute interaction, F(58, 493) = 1.75, P = 0.001. Direct post hoc comparison among the two groups that received intraduodenal Sacc showed that those for which Sacc was mixed in LiCl suppressed drinking earlier than those that received Sacc mixed in NaCl, though this interaction was only marginally significant, F(29, 319) = 1.46, P = 0.06. Whereas the Sacc in NaCl group generally began to suppress their licking around minute 14 (P = 0.01), the Sacc in LiCl group curbed licking several minutes earlier in the session (at minute 6, P = 0.02). Accordingly, rats in the Sacc in NaCl group (119.13 ± 18.77 licks/min) tended to consume more than the Sacc in LiCl group (87.97 ± 14.84 licks/min), but this difference did not achieve significance, F(1, 11) = 1.70, P = 0.22. Interestingly, however, unlike the pattern that we observed for intraduodenal DB on its own (presented in NaCl) in experiment 1 as it developed with repeated exposures, rats did not alter their lick rate pattern in response to Sacc in NaCl across probe trials, [largest F(5, 20) = 2.11, P = 0.11 for main effect of trial]. Neither did the Sacc in LiCl group alter intake in response to the arrival of Sacc to the intestine across training, despite a significant trial by minute interaction for this group [F(145, 1,015) = 1.24, P = 0.04], as subsequent analyses did not reveal a systematic change in responding across trials. Even though these comparisons among the Sacc in NaCl and Sacc in LiCl groups seem to suggest that rats for which Sacc was paired with LiCl were able to proactively suppress intake, relative to the group for which Sacc was presented in NaCl, to infer that LiCl reinforced marginally earlier Sacc detection (but notably not as early as DB detection in previous experiments), two observations suggested otherwise. First, as mentioned above, LiCl did not change the response to Sacc across training. Second, additional comparisons revealed that intraduodenal Sacc in LiCl did not evidence any advantage above plain intraduodenal LiCl. As shown in Fig. 4, rats in the Sacc in LiCl group drank slightly more than the plain LiCl group (71.77 ± 8.20 licks/min) (P = 0.17), but the pattern of licking was identical across the 30 min. Post hoc comparisons on a significant group by minute interaction [F(29, 377) = 1.54, P = 0.04] indicated one point of divergence among the two groups (at min 10, P = 0.04), where the group that received intraduodenal plain LiCl momentarily dipped below the group that received intraduodenal Sacc in LiCl. Furthermore, like the other two groups, those that received the intraduodenal LiCl did not change their response pattern across exposures, F(145, 870) = 1.14, P = 0.14.

Fig. 4.

Mean licks per minute for a NaCl solution at the sipper spout collapsed across six 30-min probe trials. Rats received a brief yoked intraduodenal infusion during the first 6 min of each 30-min session (shaded in gray) of 9.75 mM sodium saccharin (Sacc) mixed into NaCl (n = 5), Sacc mixed in LiCl (n = 8), or plain LiCl (n = 7).

All three groups received intraduodenal DB mixed in NaCl on their alternate session type. As we expected on the basis of the first experiment, all groups evidenced robust lick rate suppressions in response to the early intraduodenal DB cues, F(58, 493) = 1.51, P = 0.01, and this developed in a similar manner among groups across probe trials, F(290, 2,465) = 1.06, P = 0.24. In fact, all rats consumed less on these alternate intraduodenal DB sessions compared with their intraduodenal Sacc, regardless of whether it was presented against Sacc in NaCl (83.00 ± 15.33 licks/min) or Sacc in LiCl (57.60 ± 12.12 licks/min), or against plain LiCl (54.62 ± 12.96 licks/min) sessions, F(1, 17) = 14.23 P = 0.002.

The results of this experiment resolved an interpretive issue in experiment 1. Rats in the first experiment received DB (in NaCl) and plain LiCl on separate, but consecutive, probe sessions within each 2-day trial. Even though these rats in experiment 1 never received direct pairings among DB and LiCl, mere repeated exposure to LiCl-induced malaise on intermittent sessions may have arguably sensitized a response to DB. In the present experiment, we included a group that did not receive LiCl; instead, for this group (Sacc in NaCl) both Sacc and DB were delivered in intraduodenal NaCl. Because we did not find evidence that rats were able to detect Sacc, then this group essentially received plain NaCl and DB in NaCl on alternate sessions. Their response to DB both within and across probe trials was identical to the group that received, as in our first experiment, plain intraduodenal LiCl and DB in NaCl. Taken together, this suggests that unpaired, intermittent exposure to LiCl did not contribute to the response to intraduodenal DB (in NaCl) in experiment 1.

While it was clear that all groups discriminated intraduodenal DB from the alternate probe stimulus (Sacc or LiCl) in the present experiment, this appeared to be entirely due to detection of DB, rather than the detection of Sacc or a true discrimination of sweet and bitter. Importantly though, that the response to intraduodenal DB was distinguishable from that of intraduodenal Sacc indicates that rats were not sensing Sacc as a similarly bitter stimulus in the intestine. However, these results must be interpreted with caution. Given the demonstrated salient stimulus properties of DB, it is possible that rather than it being the case that rats did not sense intraduodenal Sacc, that presenting a strong aversive bitter stimulus as the alternative probe impeded learning about Sacc. Future studies will need to better match the relative intensities of the discriminative intraduodenal stimuli to avoid this complication.

That said, intestinally infused Sacc's failure to influence intake is consistent with previous behavioral studies with GI artificial sweeteners (41, 51). While it is unknown whether the vagus nerve is electrophysiologically responsive to Sacc, artificial sweet tastes do appear to exhibit effects on local GI physiology, upregulating glucose transport and releasing GLP-1 (23, 26, 30, 31, 44). The intraduodenal infusions were made in the proximal duodenum, where the greater part of carbohydrate absorption occurs and is correspondingly densely populated by glucose transporters and presumably their associated sweet taste sensors (37, 52). On the other hand, GLP-1-releasing L cells are more abundant in the distal small intestine (16), a site that is not likely exposed to our infusion stimulus during the infusion period; alternative infusion sites should be examined. Of course, one final and interesting possibility is that Sacc does modulate local digestive reflexes but does so via a pathway that is disconnected from other, higher-order, responses, like intake. Future experiments will need to reexamine intraduodenal Sacc taste with all of these issues in mind.

Experiment 4: blockade of the CCK-1R pathway partially attenuates the response to intraduodenal DB.

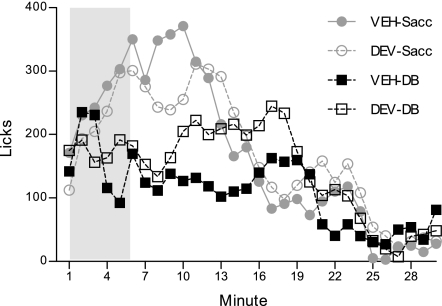

The results of experiments 1 and 2 suggested that rats are able to discern the presence of DB in the intestine within ∼2 to 3 min to inhibit intake. The results also suggested that the rats detected the termination of the DB stimulus and recovered intake with a similar latency (especially when DB was in LiCl). The temporal profile of this response strongly suggests DB detection in the intestine is mediated through a chemosensory route, as opposed to a humoral one. Interestingly, however, as mentioned previously, application of DB to GI cells stimulates the release of CCK (8, 18). While CCK is generally considered a satiety hormone that exerts its effects through both vagal and nonvagal (humoral) routes at various peripheral and central targets (3, 27, 34), it is also believed to convey stimulus-specific information in a paracrine fashion at local sensory afferent terminals (15, 36). If CCK is involved as a critical chemosensory signaling component, then pretreatment with devazepide, a CCK-1R antagonist, should abolish the early response to intraduodenal DB, compared with pretreatment with its vehicle. Thus, following probe training in experiment 3, rats were tested under these conditions (VEH-DB and DEV-DB). VEH-Sacc and DEV-Sacc tests were included for comparison.

Lick patterns across all four test sessions are presented in Fig. 5. ANOVA yielded a significant main effect of test, F(3, 51) = 4.05, P = 0.01. Intake on the VEH-DB test (113.46 ± 14.44 licks/min) was significantly reduced compared with the VEH-Sacc (169.18 ± 14.18 licks/min) and DEV-Sacc (163.87 ± 18.79 licks/min) tests (P = 0.01 and 0.02, respectively). Furthermore, DEV tended to increase intake on the intraduodenal DB test (145.80 ± 19.58 licks/min), relative to the VEH-DB test (P = 0.09). These effects of DEV on intake appear to be specific to the DB infusion stimulus, since the antagonist did not (nonspecifically) increase intake on the intraduodenal Sacc test (P = 0.99).

Fig. 5.

Mean licks per minute for a NaCl solution at the sipper spout on four 30-min test sessions. Rats (n = 18) were given an intraperitoneal injection of the CCK-1R antagonist devazepide (DEV) (75 μg/ml, 4 ml/kg) or its vehicle (VEH) 30 min prior to the start of the test session. Rats received an intraduodenal infusion (yoked to licking) of either 10 mM DB in NaCl or 9.75 mM Sacc in NaCl during the 6 min (shaded in gray) of each test session.

There was an overall test by minute interaction as well, F(87, 1,479) = 3.01, P = 0.00001. Comparable to the probe training pattern of data from experiments 1 and 2, rats transiently suppressed licking on the VEH-DB test during minutes 5–12 (largest P = 0.05 at minute 7), compared with the VEH-Sacc test, F(29, 493) = 5.25, P = 0.00001. DEV appeared to delay this initial lick suppression by ∼3 min (different from intraduodenal Sacc at minutes 8–10, largest P = 0.02 at minute 10), F(29, 493) = 4.52, P = 0.00001. Furthermore, DEV appeared to alleviate the later effects of DB, as intake remained slightly elevated in the concluding minutes of the test, though direct comparison of the VEH- and DEV-DB tests did not yield a significant test by minute interaction, F(29, 493) = 1.18, P = 0.24. Taken together, the data suggest that DEV interfered with the response to DB but did not completely abolish the effect.

Experiment 5: rats track and respond rapidly to intraduodenal DB presented (unexpectedly) later in the session.

Although several features of the response to intraduodenal DB point to a chemosensory transduction mechanism, since our rats received extensive experience with infusions of DB in the first 6 min of the session, it was also possible that the rats came to expect with some probability, a DB infusion within those early minutes and were, therefore, more prepared to initiate an anticipatory humoral response, upon detection. It was of interest then to determine whether these rats that had received extensive prior experience with the early infusion (minutes 1–6) tracked and responded to intraduodenal DB, when it was administered (unexpectedly) later in the session, after a relatively prolonged licking bout on the safe NaCl only, to then adjust intake. Thus, here, we shifted the infusion period to minutes 8–13 for two tests—one in which the intraduodenal stimulus was DB and the other in which the intraduodenal stimulus was Sacc.

As shown in Fig. 6, rats decreased their lick rate in response to the shifted DB infusion, compared with the shifted Sacc infusion (significant at minute 16, P = 0.01), F(29, 348) = 1.81, P = 0.008. Thus, rats readily tracked the quality of the conditions in the GI tract, even later in the session to curb ongoing intake, closely replicating the temporal stimulus response contiguity that we observed for the minutes 1–6 infusion period used in experiments 1 and 2.

Fig. 6.

Mean licks per minute for NaCl at the sipper spout on two test sessions. Rats (n = 13) received intraduodenal infusions (yoked to licking) of either 10 mM DB in NaCl or 9.75 mM Sacc in NaCl, during minutes 8–13 of the session (shifted, shaded in gray).

DISCUSSION

The present experiments demonstrated that rats were able to quite rapidly sense the arrival of an aversive bitter stimulus DB in the intestine to inhibit ongoing intake, which minimized further accumulation of the noxious agent in the intestine. The development of this early response to intraduodenal DB across probe trials suggested that the longer latency unconditioned aversive effects in the initial trials reinforced the detection of the immediate taste cues during the later trials. Thus, rats developed a taste aversion to DB in the intestine. Consistent with this, use of LiCl as the vehicle for to the DB infusate accelerated the emergence of the early response across trials and produced a more temporally contiguous stimulus-response pattern. That the transient lick suppression was stimulus bound is indicative of an underlying chemosensory mechanism. It appears that CCK is not an essential signaling factor, as devazepide did not completely abolish the response to DB in the intestine.

In particular, two features of the early lick pattern support the conclusion that DB elicited a signal that was transduced via a chemosensory route. First, following some training, the latency to curb lick rate in response to intraduodenal DB was ∼2–3 min, likely preceding the reception of a humoral signal. Because humoral signals must accumulate to a threshold level in the bloodstream and circulate to distant target organs, their effects are generally well delayed from stimulus onset (e.g., latency to affect ingestive behavior, ∼5–30 min after meal instillation) (2, 28). Moreover, it is not likely that this rapid latency to respond to DB was due to express mobilization of a humoral signal in anticipation of the consequences of the bitter compound, since rats responded with the same latency when the DB infusion was unexpectedly shifted. Second, rats generally only abstained from licking for ∼4–5 min, following DB infusions, before resuming normal intake. This is, likewise, inconsistent with a humoral basis, for just as these messengers require time to accrue, humoral signals wane relatively slowly; therefore, hormone-driven responses do not tend to reverse so rapidly (e.g., for ingestive behavior, 15 min to hours, following the meal) (2, 28).

When examined with the discrete infusion procedure used in the present series, as opposed to extended infusions in previous work, the temporal response profile to intraduodenal DB is not consistent with the previously suggested humoral basis (17). Furthermore, our estimates of response latency are particularly conservative for two reasons: 1) infusion lines contained ∼0.40 ml of 0.12 M NaCl for the start of each session; thus, the vehicle in the delivery lines and catheter was infused with the first ∼80–100 licks of the session, before the DB infusate even reached the intestine, and 2) under the deprivation conditions used here, the rats, given the opportunity to replete thirst, were perhaps more tolerant of an aversive intraduodenal stimulus.

Previously, Hao et al. (18) demonstrated that an infusion of a GI bitter taste mixture into the stomach produces c-Fos activation in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), which is blocked by vagotomy, thus suggesting that these bitter stimuli engage vagal chemoreceptors to relay a code centrally. Additionally, it was proposed that for DB, in particular, CCK was a critical factor in the sensory cascade, since Hao and coworkers (18) observed that NTS c-Fos was completely abolished in CCK-1R-null mice and mice pretreated with devazepide. But whether this pathway is essential for the control of ingestive behavior remains to be determined. Glendinning et al. (17) hypothesized that GI DB signals may be relayed by an alternative humoral pathway to reinforce flavor avoidance, though this, of course, does not necessarily preclude CCK as a key humoral factor. Because both c-Fos activation measures as used in the Hao et al. study (18) and conditioned flavor avoidance training parameters, as used in the Glendinning et al. (17) and Hao et al. (19) studies employed long intervals between stimulus arrival and response measurement, permitting a number of different intervening events (both paracrine and endocrine), with nonspecific task demands, these procedures may exploit different types of signals.

Hence, in the present study, whether CCK mediated the inhibition of drinking by the intraduodenal DB stimulus and lick response was examined. Even though this tightly coupled temporal relationship delineated with the present paradigm seemingly favored a chemosensory/paracrine CCK effect, pretreatment with devazepide only partially attenuated the early response to intraduodenal DB. This partial effect was unexpected given devazepide completely abolished the c-Fos response to GI DB in the Hao et al. (18) study, but key differences between that study and the present one, including number of exposures to DB (1 vs. 6), training history (although there was no training group, in NaCl vs. in LiCl, differences were noted with respect to devazepide blockade in the present study), infusion site (stomach vs. intestine), infusion volume (1 ml vs. ∼4–5 ml), deprivation state (food vs. food and water), and species (mouse vs. rat), discourage a direct comparison. Whatever the case, the partial effect was not likely due to a subthreshold devazepide delivery, since we used both a dose and route that have most effectively mitigated the effects of high levels of exogenous CCK and nutrient-induced endogenous CCK, previously reasoned to work through a paracrine mechanism, without producing nonspecific effects on intake (6, 11). That said, it is possible that the dose of DB used here is a more potent stimulator of CCK than has been examined before with respect to exogenous and endogenous CCK, such that a higher dose of devazepide may be needed to completely abolish the effect. Alternatively, DB, at the concentration used in the present experiments, may additionally stimulate other non-CCK signaling systems. As such, CCK may signal only one aspect of the DB stimulus, be it bitter taste or some other stimulus property (e.g., irritation), while other features of the stimulus are signaled by factors that are yet unknown. On the other hand, rather than (or in addition to) directly transmitting information about DB, CCK may modulate a separate signaling system responding to the intestinal bitter taste cue. Indeed, CCK has been known to synergistically interact with other peptides, like 5-HT and leptin, in the transmission of postoral meal-related stimuli (21, 35). Future work will need to determine whether these or other signaling mechanisms are involved in intraduodenal DB sensing.

Perspectives and Significance

Throughout this report we have referred to DB as a bitter stimulus, simply because it is a selective agonist for a receptor belonging to the bitter T2R family, which has also been localized in the postoral GI tract, that evokes a similar sensation to other bitter tastants (e.g., quinine) upon contact with lingual receptors (7, 43, 50). However, it is unclear whether the DB stimulus that the rats are detecting in the intestine is encoded as bitter. For instance, rats may detect and discriminate two intraduodenal infusates on the basis of some other cue property, like pH or osmolality, though it is unclear how these particular factors contributed to the discrimination observed here, since rats clearly differentiated between intraduodenal DB (in NaCl) and Sacc (in NaCl), two solutions that had near-identical pH and osmolality (see Table 1). But even beyond those types of stimulus features, DB may have been sensed or coded as some other type of stimulus (e.g., irritation, anesthetization). Despite some contribution of CCK to the signal, it is not likely that DB produced a satiety-like sensation, given the transient duration of the suppression it produced. Conveniently, though, the procedure developed here can be used to determine on what stimulus quality basis discriminations are made. Indeed, more extensive work with this basic procedure, adapted for discrimination and generalization tests, with a litany of chemicals at varying concentrations, could eventually construct GI taste categories and rule out extraneous cue features. The contributions of specific taste receptors in the GI tract (e.g., T1R and T2R) and primary sensory afferents (e.g., vagal) to these responses with the use of taste receptor knockouts and selective afferent transections, respectively, will be additionally critical to further elucidating GI taste coding.

To our knowledge, the present experiments provide the first demonstration that rats condition a taste aversion in the intestine. At one time, GI chemoreceptors were hypothesized to bridge the perplexingly long temporal delay between the oral tastant and visceral malaise that conventional oral CTAs withstood, by contributing sensory information about the tastant in closer contiguity with illness (e.g, 39, 29). The long delay aspect was later explained by other features of CTA, but studies by Tracy et al. (47) and Tracy and Davidson (48) supported the notion that information about a postoral nutritive stimulus (e.g., Polycose) paired with LiCl converges on central taste areas, where it is later accessed when the oral taste receptors sample the same stimulus (Polycose) to, accordingly, inform the rat to avoid its ingestion. Thus, in addition to adjusting the valence of a neutral oral flavor to reflect the respective positive (e.g., caloric) or negative (e.g., toxic) consequences, as in the case of conditioned (oral) flavor/taste- preference (CFP), avoidance or aversion, it appears that chemical features of the postoral stimulus may be encoded in these types of gustatory associations. Importantly, the results of the present study extend this view by first revealing that a postoral stimulus is detected and transduced at a preabsorptive receptor site within the intestine, providing a putative pathway by which its chemical features are conveyed. Further, it appears that this intestinal taste stimulus directly associates with consequent events, and the signal is accordingly modified and incorporated in the control of intake, as reflected in a change in subsequent responding to same stimulus upon its arrival in the intestine. Taken together, these intestinal taste aversions highlight a more dynamic role for GI chemoreceptors than was previously appreciated (42). That is, rather than providing comparably crude, inflexible, sensory information to feedback on ingestive behavior, it appears that taste-like signals in the postoral GI tract are themselves actively revised with experience.

In conclusion, several features of this series of experimentation on DB encourage further use of the present paradigm focusing on early preabsorptive signals in the intestines and, theoretically, the development and use of its appetitive counterpart (intestinal flavor preference), to survey detection and discrimination of other tastants in the GI tract. Considering the close association among chemoreceptors of the GI tract and metabolic and behavioral controls of food intake, an understanding of GI taste categories will likely lead to the development of taste ligands and foods that correct deficiencies in metabolic processes associated with obesity (e.g., glucose homeostasis) and maximize postoral feedback on satiety to prevent overconsumption.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Grants R01 DK-027627 and P01 HD05211 from the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank T. Karam and A. Birge for their assistance with animal care. This report contains part of a Ph.D. thesis by L.A. Schier. A portion of this report appeared in abstract form at the 19th Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Ingestive Behavior, 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ackroff K, Yiin YM, Sclafani A. Post-oral infusion sites that support glucose-conditioned flavor preferences in rats. Physiol Behav 99: 402–411, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anini Y, Fu-Cheng X, Cuber JC, Kervran A, Chariot J, Roz C. Comparison of the postprandial release of peptide YY and proglucagon-derived peptides in the rat. Pflügers Arch 438: 299–306, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baptista V, Browning KN, Travagli RA. Effects of cholecystokin-8s in the nucleus tractus solitaries of vagally deafferented rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1092–R1100, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bezençon C, le Coutre J, Damak S. Taste-signaling proteins are coexpressed in solitary intestinal epithelial cells. Chem Senses 32: 41–49, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bezençon C, Fürholz A, Raymond F, Mansourian R, Métairon S, Le Coutre J, Damak S. Murine intestinal cells expressing Trpm5 are mostly brush cells and express markers of neuronal and inflammatory cells. J Comp Neurol 509: 514–525, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brenner LA, Ritter RC. Type A CCK receptors mediate satiety effects of intestinal nutrients. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 54: 625–631, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chandrashekar J, Mueller KL, Hoon MA, Adler E, Feng L, Guo W, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ. T2Rs function as bitter taste receptors. Cell 100: 703–711, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen MC, Wu SV, Reeve JR, Jr, Rozengurt E. Bitter stimuli induce Ca2+ signaling and CCK release in enteroendocrine STC-1 cells: Role of L-type voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C726–C739, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Covasa M, Ritter RC. Reduced sensitivity to the satiation effect of intestinal oleate in rats adapted to high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R279–R285, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Covasa M, Grahn J, Ritter RC. Reduced hindbrain and enteric neuronal response to intestinal oleate in rats maintained on high-fat diet. Auton Neurosci 84: 8–18, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Covasa M, Ritter RC. Attenuated satiation response to intestinal nutrients in rats that do not express CCK-A receptors. Peptides 22: 1339–1348, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Covasa M. Deficits in gastrointestinal responses controlling food intake and body weight. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: R1423–R1439, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daly DM, Park SJ, Valinsky WC, Beyak MJ. Impaired intestinal afferent nerve satiety signaling and vagal afferent excitability in diet induced obesity in the mouse. J Physiol 589: 2857–2870, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dyer J, Salmon KS, Zibrik L, Shirazi-Beechey SP. Expression of sweet taste receptors of the T1R family in the intestinal tract and enteroendocrine cells. Biochem Soc Trans 33: 302–305, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eastwood C, Maubach K, Kirkup AJ, Grundy D. The role of endogenous cholecystokinin in the sensory transduction of luminal nutrient signals in the rat jejunum. Neurosci Lett 254: 145–148, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eissele R, Göke R, Weichhardt U, Fehmann HC, Arnold R, Göke B. Glucagon-like peptide-I cells in the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas of rat, pig, and man. Eur J Clin Invest 22: 283–291, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Glendinning JI, Yiin YM, Ackroff K, Sclafani A. Intragastric infusion of denatonium conditions flavor aversions and delays gastric emptying in rodents. Physiol Behav 93: 757–765, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hao S, Sternini C, Raybould HE. Role of CCK1 and Y2 receptors in activation of hindbrain neurons induced by intragastric administration of bitter taste receptor ligands. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R33–R38, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hao S, Dulake M, Espero E, Sternini C, Raybould HE, Rinaman L. Central fos expression and conditioned flavor avoidance in rats following intragastric administration of bitter taste receptor ligands. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R528–R536, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hass N, Schwarzenbacher K, Breer H. T1R3 is expressed in brush cells and ghrelin-producing cells of murine stomach. Cell Tissue Res 339: 493–504, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hayes MR, Covasa M. CCK and 5-HT act synergistically to suppress food intake through simultaneous activation of CCK-1 and 5-HT-3 receptors. Peptides 26: 2322–2330, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hofer D, Puschel B, Drenckhahn D. Taste receptor-like cells in the rat gut identified by expression of a-gustducin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 6631–6634, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jang HJ, Kokrashvili Z, Theodorakis MJ, Carlson OD, Kim BJ, Zhou J, Kim HH, Xu X, Chan SL, Juhaszova M, Bernier M, Mosinger B, Margolskee RF, Egan JM. Gut-expressed gustducin and taste receptors regulate secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15069–15074, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Katz DB, Nicolelis MA, Simon SA. Nutrient tasting and signaling mechanisms in the gut. IV. There is more to taste than meets the tongue. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 278: G6–G9, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. King CT, Garcea M, Spector AC. Glossopharyngeal nerve regeneration is essential for the complete recovery of quinine-stimulated oromotor rejection behaviors and central patterns of neuronal activity in the nucleus of the solitary tract in the rat. J Neurosci 20: 8426–8434, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kokrashvili Z, Mosinger B, Margolskee RF. Taste signaling elements expressed in gut enteroendocrine cells regulate nutrient-responsive secretion of gut hormones. Am J Clin Nutr 90: 822S–825S, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Y, Owyang C. Pancreatic secretion evoked by cholecystokinin and non-cholecystokinin-dependent duodenal stimuli via vagal afferent fibres in the rat. J Physiol 494: 773–782, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liddle RA, Green GM, Conrad CK, Williams JA. Proteins, but not amino acids, carbohydrates, or fats, stimulate cholecystokinin secretion in the rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 251: G243–G248, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lindberg MA, Beggs AL, Chezik DD, Ray D. Flavor-toxicosis learning: Tests of 3 hypotheses of long delay learning. Physiol Behav 29: 439–442, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mace OJ, Affleck J, Patel N, Kellett GL. Sweet taste receptors in rat small intestine stimulate glucose absorption through apical GLUT2. J Physiol 582: 379–392, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Margolskee RF, Dyer J, Kokrashvili Z, Salmon KS, Ilegems E, Daly K, Maillet EL, Ninomiya Y, Mosinger B, Shirazi-Beechey SP. T1R3 and gustducin in gut sense sugars to regulate expression of Na+-glucose cotransporter 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15075–15080, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin JR, Chenga FY, Novin D. Acquisition of learned taste aversion following bilateral subdiaphragmatic vagotomy in rats. Physiol Behav 21: 13–17, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mediavilla C, Molina F, Puerto A. Concurrent conditioned taste aversion: A learning mechanism based on rapid neural versus flexible humoral processing of visceral noxious substances. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 29: 1107–1118, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moran TH, McHugh PR. Cholecystokinin suppresses food intake by inhibiting gastric emptying. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 242: R491–R497, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peters JH, McKay BM, Simasko SM, Ritter RC. Leptin-induced satiation mediated by abdominal vagal afferents. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R879–R884, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Raybould HE, Lloyd KCK. Integration of postprandial function in the proximal gastrointestinal tract: Role of CCK and sensory pathways. Ann NY Acad Sci 713: 143–156, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rider AK, Schedl HP, Nokes G, Shining S. Small intestinal glucose transport: Proximal-distal kinetic gradients. J Gen Physiol 50: 1173–1182, 1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rusiniak KW, Garcia J, Hankins WG. Bait shyness: Avoidance of the taste without escape from the illness in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol 90: 460–467, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schneider K, Wothe K. Contribution of naso-oral and post-ingestional factors in taste-averson learning in the rat. Behav Neural Bio 25: 30–38, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sclafani A, Ackroff K, Schwartz GJ. Selective effects of vagal deafferentation and celiac-superior mesenteric ganglionectomy on the reinforcing and satiating action of intestinal nutrients. Physiol Behav 78: 285–294, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sclafani A, Glass DS, Margolskee RF, Glendinning JI. Gut T1R3 sweet taste receptors do not mediate sucrose-conditioned flavor preferences in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: R1643–R1650, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smith GP. The direct and indirect controls of meal size. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 20: 41–46, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Spector AC, Kopka SL. Rats fail to discriminate quinine from denatonium: Implications for the neural coding of bitter-tasting compounds. J Neurosci 22: 1937–1941, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Steinert RE, Gerspach AC, Gutmann H, Asarian L, Drewe J, Beglinger C. The functional involvement of gut-expressed sweet taste receptors in glucose-stimulated secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY). Clin Nutr 30: 524–532, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sternini C. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. IV Functional implications of bitter taste receptors in gastrointestinal chemosensing. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G457–G461, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sutherland K, Young RL, Cooper NJ, Horowitz M, Blackshaw LA. Phenotypic characterization of taste cells of the mouse small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G1420–G1428, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tracy AL, Phillips RJ, Chi MM, Powley TL, Davidson TL. The gastrointestinal tract “tastes” nutrients: Evidence from the intestinal taste aversion paradigm. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R1086–R1100, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tracy AL, Davidson TL. Comparison of nutritive and nonnutritive stimuli in intestinal and oral conditioned taste aversion paradigms. Behav Neurosci 120: 1268–1278, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Walls EK, Phillips RJ, Wang FB, Holst MC, Powley TL. Suppression of meal size by intestinal nutrients is eliminated by celiac vagal deafferentation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 269: R1410–R1419, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu SV, Rozengurt N, Yang M, Young SH, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. Expression of bitter taste receptors of the T2R family in the gastrointestinal tract and enteroendocrine STC-1 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 2392–2397, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yin TH, Tsai CT. Effects of glucose on feeding in relation to routes of entry. J Comp Physiol Psychol 85: 258–264, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yoshikawa T, Inoue R, Matsumoto M, Yajima T, Ushida K, Iwanaga T. Comparative expression of hexose transporters (SGLT1, GLUT1, GLUT2, and GLUT5) throughout the mouse gastrointestinal tract. Histochem Cell Biol 135: 183–94, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zafra MA, Molina F, Puerto A. Learned flavor preferences induced by intragastric administration of rewarding nutrients: Role of capsaicin-sensitive vagal afferent fibers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R635–R641, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]