Abstract

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a component of the renin-angiotensin system, and its expression and activity have been shown to be reduced in cardiovascular diseases. Enzymatic activity of ACE2 is commonly measured by hydrolysis of quenched fluorescent substrates in the absence or presence of an ACE2-specific inhibitor, such as the commercially available inhibitor DX600. Whereas recombinant human ACE2 is readily detected in mouse tissues using 1 μM DX600 at pH 7.5, the endogenous ACE2 activity in mouse tissues is barely detectable. We compared human, mouse, and rat ACE2 overexpressed in cell lines for their sensitivity to inhibition by DX600. ACE2 from all three species could be inhibited by DX600, but the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for human ACE2 was much lower (78-fold) than for rodent ACE2. Following optimization of pH, substrate concentration, and antagonist concentration, rat and mouse ACE2 expressed in a cell line could be accurately quantified with 10 μM DX600 (>95% inhibition) but not with 1 μM DX600 (<75% inhibition). Validation that the optimized method robustly quantifies ACE2 in mouse tissues (kidney, brain, heart, and plasma) was performed using wild-type and ACE2 knockout mice. This study provides a reliable method for measuring human, as well as endogenous ACE2 activity in rodents. Our data underscore the importance of validating the effect of DX600 on ACE2 from each particular species at the experimental conditions employed.

Keywords: DX600; quenched fluorescent substrate; (7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl)acetyl-Ala-Pro-Lys(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-OH; enzyme inhibition

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a metallocarboxypeptidase that hydrolyzes the octapeptide ANG II, as well as several other small peptides (6, 26, 28). ANG II signaling promotes vasoconstriction and elevation of blood pressure (32). By decreasing the concentration of ANG II and increasing the concentration of the heptapeptide ANG-(1–7), whose signaling tends to be opposite of that of ANG II, ACE2 can diminish the effects of ANG II, while loss of ACE2 exacerbates ANG II-driven processes (11, 14). To assess how ACE2 abundance affects biological processes, it is essential to be able to accurately quantify the enzymatic activity of ACE2, especially since there can be discordance in the regulation of ACE2 at the levels of mRNA, protein, and enzymatic activity (24, 29, 30). ACE2 activity is commonly quantified using the quenched fluorescent substrates (7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl)acetyl-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-Ala-Pro-Lys(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-OH [Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp)] and (7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl)acetyl-Ala-Pro-Lys(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-OH [Mca-APK(Dnp)] (28). However, these fluorogenic substrates are not specific for ACE2. Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp) can, for example, also be hydrolyzed by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and caspase 1 (interleukin-1β-converting enzyme) (9, 29). Specificity is ensured by assessing inhibition of activity with an ACE2-specific inhibitor (5, 8, 29). The two commonly used ACE2 inhibitors are MLN-4760 (compound 16 in Ref. 4) and DX600 (16), of which only the latter is commercially available.

Our laboratory has previously used 1 μM of DX600 to detect activity from a human ACE2 transgene expressed in mice (1, 10). While the human transgene activity is readily detected, we have noted that the endogenous mouse ACE2 activity in the pancreas and central nervous system is barely detectable by this method, even though these tissues express significant levels of ACE2 protein, as detected by immunohistochemistry and Western blot analysis (1, 7). DX600 was originally identified on the basis of its ability to inhibit purified ACE2 (16). We speculated that endogenous mouse ACE2 was underestimated due to insufficient inhibition by DX600. Therefore, we tested and confirmed the hypothesis that ACE2 from rodents has a lower sensitivity to inhibition by DX600 than human ACE2. An optimized assay allowing quantification of rodent ACE2 expressed in cell lines and in several mouse tissues is further described in this report.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

The INS-1-derived rat insulinoma cell line 832/13 (15) was a kind gift from Dr. Christopher B. Newgard, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC. The mouse neuroblastoma cell line Neuro-2a was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA; cat. no. CCL-131).

Animals.

Animal use was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. Three male C57BL/6J wild-type mice and three male ACE2 knockout mice in the same genetic background (14) at an age of 9 wk were euthanized under anesthesia. Brain, heart, and kidney were quickly removed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80° C. Plasma was collected and stored at −80°C.

Plasmids.

An expression plasmid, hACE2/pcDNA3.1, for human ACE2 in the pcDNA3.1(+) background was a kind gift from Dr. Curt D. Sigmund (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). Expression plasmids for rat and mouse ACE2 were made by inserting the open reading frames for ACE2 between NheI and XhoI sites of the vector backbone of hACE2/pcDNA3.1. The open reading frames were PCR-amplified from cDNA from mouse heart and 832/13 cells. The sequence of the mouse ACE2 insert is identical to base 331–2748 of GenBank sequence NM_001130513.1. The sequence of the rat ACE2 insert is identical to base 1–2418 of GenBank sequence NM_001012006.1, except for the stop codon TAA replaced with stop codon TAG. In vitro mutagenesis D149N (GAT→AAT) and N368D (AAC→GAC) of mouse ACE2 in the expression plasmid was performed.

Transfection.

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at concentrations of 1 × 106 cells/well and 2 × 106 cells/well for the Neuro-2a and 832/13 cell lines, respectively, the day before transfection. Cells were transfected with 2 μg expression plasmid and 10 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) per well in 1 ml medium DMEM without serum, glucose, or antibiotics (23). After incubation for 4 h, the transfection medium was replaced with normal maintenance medium for the respective cell lines. Cells were incubated for an additional 44 h.

Western blot analysis.

The protein content of samples was quantified with a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Western blotting of whole cell lysates was conducted as previously described (22). Primary antibodies were anti-ACE2 (sc-20998; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and anti-gamma-tubulin (T5192; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Images were captured with a Fujifilm luminescent image analyzer LAS-1000plus from Fuji Photo Film.

ACE2 assay.

Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp) and Mca-APK(Dnp) were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA), respectively. DX600 was purchased from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Burlingame, CA). Cells or ground-up tissue were suspended in 0.5% Triton X-100 in ACE2 reaction buffer. Suspensions were sonicated on ice and centrifuged at 20,800 g for 5 min at 4°C. Supernatants were stored at −80°C and later used for activity measurements. Samples were diluted in 0.5% Triton X-100 in ACE2 reaction buffer to enter a range in which fluorescence is a linear function of the incubation time. Each assay contained 0.2–0.5 μg protein for cell culture extracts, 5 μg protein for kidney extracts, and 10 μg protein for heart and brain extracts. Aliquots of plasma samples were assayed undiluted. Except for experiments aimed at determining substrate and inhibitor affinity for ACE2, assays were run at 37°C in ACE2 reaction buffer containing 100 μM Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp), 50 μM Mca-APK(Dnp), or 10 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) ± inhibitors in a total volume of 100 μl. ACE2 reaction buffer was 1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM ZnCl2, and 75 mM Tris·HCl at different pH values. To inhibit ACE, 10 μM of the ACE inhibitor captopril was included in assays with mouse tissue samples. Fluorescence emission at 405 nm, after excitation at 320 nm, was measured in a Spectramax M2 microplate reader from Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, CA). With Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp), the slope of fluorescence development between 10 and 120 min of incubation was calculated. With Mca-APK(Dnp), the slope between 10 and 60 min was calculated. Blank values were obtained with extraction buffer only as the sample and were subtracted from the hydrolysis rates of the sample extracts. Hydrolysis rates were quantified as fluorescence units per minute per amount of protein or per volume of plasma. For determination of the Michaelis constant Km and the dissociation constant Ki between DX600 and free enzyme, reactions were run at pH 6.5 at ambient temperature (22.1–23.9°C) for 30 min to ensure initial reaction velocities and minimize potential DX600 degradation. Concentrations of Mca-APK(Dnp) were 2, 5, 10, 15, 25, and 50 μM. Concentrations of DX600 were 0, 50, 75, 100, 150, 250, and 500 nM for human ACE2 and 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 μM for rat and mouse ACE2. Each reaction contained 0.2 μg protein from extracts of 832/13 cells transfected with the ACE2 expression plasmids. Values for kinetic parameters, including Km and Ki, were fitted to a mixed model of enzyme inhibition with least squares nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Four independent estimations were made of each parameter.

Statistics.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Hydrolysis rates were analyzed with repeated-measures ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 5. Bonferroni adjustments were made for multiple post hoc contrasts of means in the absence and presence of DX600. Symbols * and *** in the figures indicate statistically significant differences at the 5% and 0.1% significance levels, respectively.

RESULTS

Rodent ACE2 is less sensitive to DX600 inhibition than human ACE2.

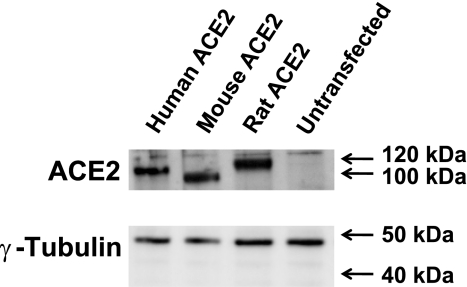

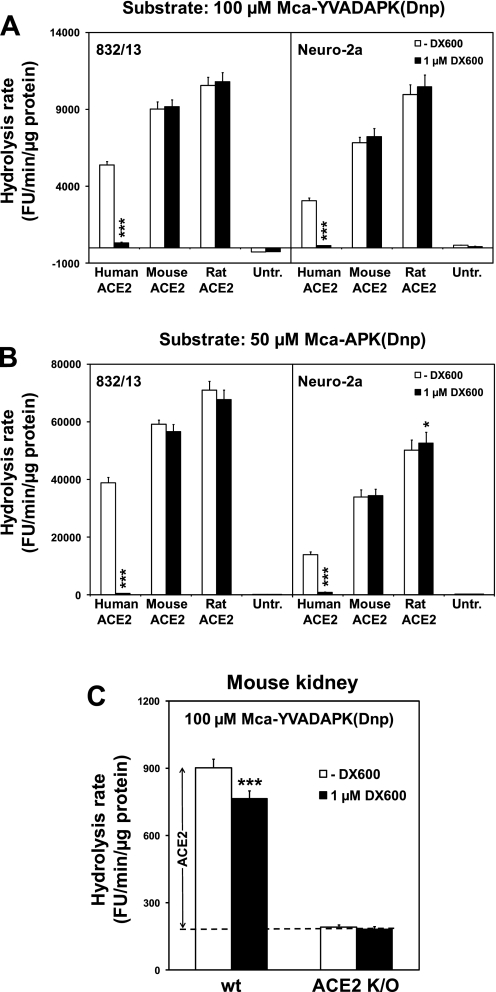

Human, rat, and mouse ACE2 were expressed in 832/13 and Neuro-2a cells by transient transfection with ACE2 expression plasmids. In 832/13 cells, the plasmids induce expression of ACE2 protein with apparent molecular weights between 100 and 120 kDa (Fig. 1). At conditions previously used for detecting activity from a transgene encoding human ACE2 [100 μM of the quenched fluorescent substrate Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp) at pH 7.5], human ACE2 activity is strongly (>93%) inhibited by 1 μM DX600 in both pancreatic and neuronal cells, while rat and mouse ACE2 activities are not significantly inhibited (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained when the substrate was 50 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) (Fig. 2B). The apparent significant upregulation of rat ACE2 by 1 μM DX600 in Neuro-2a cells is likely a statistical type I error. Note that at the dilution required to accurately measure the overexpressed ACE2 activities (0.5 μg protein per reaction for Fig. 2, A and B), there is negligible endogenous ACE2 activity.

Fig. 1.

Expression of human, mouse, and rat ACE2. Western blotting for detection of ACE2 and the loading control γ-tubulin was performed for 832/13 cells transfected with the ACE2 expression plasmids or for untransfected cells. Each lane was loaded with lysate containing 4 μg of protein. The blot shows results from one of two independent transfection experiments giving similar results.

Fig. 2.

Murine ACE2 differs from human ACE2 in being inefficiently inhibited by 1 μM DX600. A and B: 832/13 and Neuro-2a cells were transfected with expression plasmids for human, mouse, and rat ACE2. Untransfected cells (Untr.) were controls. Four independent transfection experiments were conducted for each cell line. Hydrolysis rates of 100 μM Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp) (A) and 50 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) (B) were measured at pH 7.5 in the absence or presence of 1 μM DX600. C: hydrolysis rates of 100 μM Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp) at pH 7.5 for kidney extracts from wild-type (wt) and ACE2 knockout (K/O) mice were measured in the absence and presence of 1 μM DX600. The stippled line indicates the average hydrolytic activity of knockout mouse extracts in the presence and absence of DX600, which is a parameter for hydrolysis of Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp) by non-ACE2 enzymes. This parameter is used to calculate the estimated true ACE2 activity in wild-type mice. *Significant difference, P < 0.05. ***Significant difference, P < 0.001.

It has been reported that another commonly used ACE2 inhibitor, MLN-4760, does not quench ACE2 activity measured with Mca-APK(Dnp) in mouse tissues (29). We speculated that amino acid differences between human and rodent ACE2 molecules around the active sites might lead to differences in sensitivity to ACE2 inhibitors. Of the amino acid residues of human ACE2 that interact with MLN-4760 (27), there are two residues that differ between the species: residue 149 is asparagine in human, but aspartic acid, in the mouse and rat; and residue 368 is aspartic acid in human, but asparagine in mouse and rat. We assessed the sensitivity of mouse ACE2 with D149N and N368D mutations to inhibition by 1 μM DX600. These mutations did not increase the sensitivity to inhibition (data not shown), indicating that other amino acid residue differences between human and rodent ACE2 cause the species-dependent DX600 sensitivity.

We evaluated the use of 1 μM DX600 to detect endogenous ACE2 in mouse kidneys, when ACE2 is measured with 100 μM Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp) at pH 7.5 (Fig. 2C). The hydrolysis rate of Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp) of kidney extracts from ACE2 knockout mice represents the non-ACE2 enzymes capable of cleaving the fluorogenic substrate. As DX600 has no significant effect on the non-ACE2 enzymes, the best estimate of their activity level is the average of the hydrolysis rates for the knockout mice in the absence and presence of DX600. Assuming that the same amount of non-ACE2 enzymes exists in wild-type mice as in knockout mice, we estimate the true ACE2 hydrolysis rate in the wild-type mice as the rate in the absence of DX600 minus the average of the hydrolysis rates for the knockout mice. For the wild-type kidney, 1 μM DX600 significantly decreased the hydrolysis rate of the substrate, but only 19% of the estimated true ACE2 activity was detected (Fig. 2C).

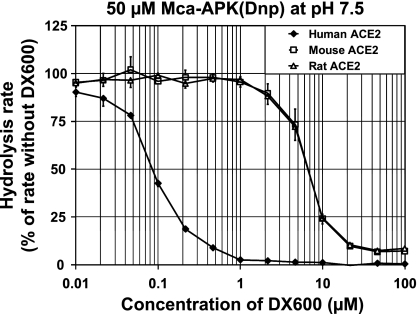

With Mca-APK(Dnp) as ACE2 substrate, we generated dose-response curves (Fig. 3). Under these conditions, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for human ACE2 is ∼0.09 μM DX600, while the IC50 for rat and mouse ACE2 is ∼7 μM DX600.

Fig. 3.

Species-specific sensitivity to DX600. Dose-response curves were generated for the hydrolysis rate of 50 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) at pH 7.5 as a function of the concentration of DX600. Extracts from cells transfected with expression plasmids for human, mouse, and rat ACE2 were used. The data represent the mean ± SE for extracts from two transfection experiments with 832/13 cells and two transfection experiments with Neuro-2a cells.

An optimized method for detecting rodent ACE2 with DX600.

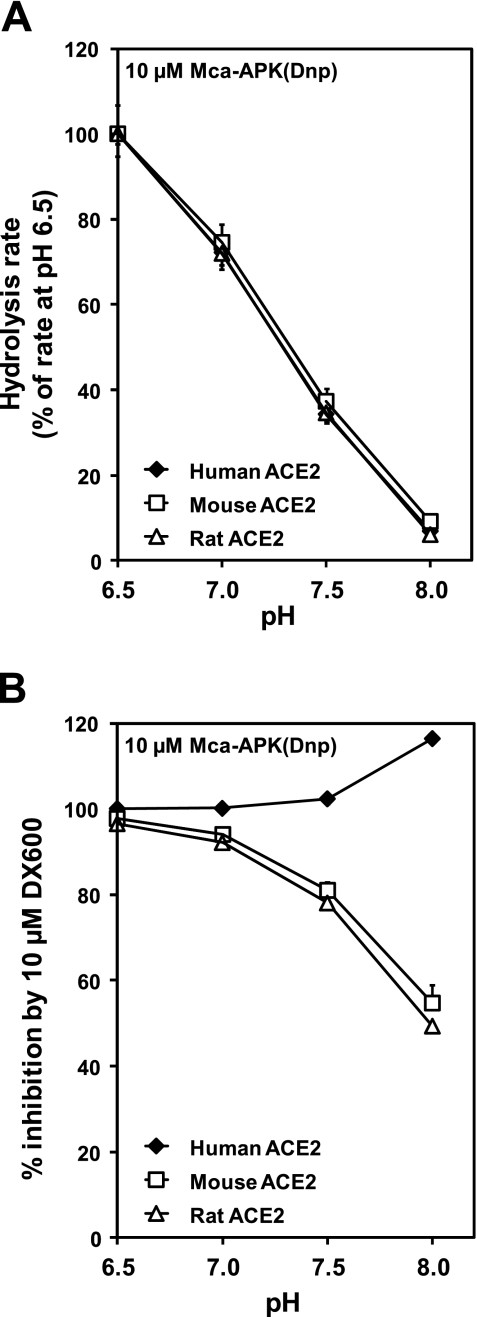

While rodent ACE2 expressed in 832/13 or Neuro-2a cell lines was insignificantly inhibited by 1 μM DX600 at the employed experimental conditions, another group has reported near-complete inhibition of mouse lung ACE2 with 1 μM DX600 at slightly different experimental conditions, including a lower pH (6.5) and a lower concentration (10 μM) of Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp) (19). In our hands, these conditions allowed some inhibition of mouse ACE2 expressed in 832/13 cells by DX600 (<75%, data not shown), but not to the degree as in Ref. 19. However, 10 μM DX600 run in an assay with 10 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) at pH 6.5 inhibited mouse and rat ACE2 by 98% and 97%, respectively (Fig. 4). The change in pH from 7.5 to 6.5 is important, as it causes both a higher hydrolysis rate of Mca-APK(Dnp) (Fig. 4A), as well as a higher degree of inhibition of rodent ACE2 by DX600 (Fig. 4B). Human ACE2 has the same pH activity profile as rodent ACE2 but is completely inhibited by DX600 in the whole pH range from 6.5 to 8.0 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

pH dependency of ACE2 activity assays. Extracts from four transfections of 832/13 cells with expression plasmids for human, mouse, and rat ACE2 were assayed. A: hydrolysis rates of 10 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) were measured at different pH values in the absence of DX600. For ACE2 from each species, the hydrolysis rate at pH 6.5 was set to 100%. B: inhibition of the hydrolysis of 10 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) by 10 μM DX600 was measured at different pH values.

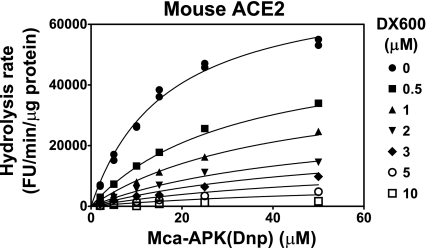

To compare binding of DX600 to human, rat, and mouse ACE2 in activity assays with Mca-APK(Dnp) at pH 6.5, we estimated the Michealis constant Km and the dissociation constant Ki as illustrated in Fig. 5. ACE2 from the three species have Km values for the fluorogenic substrate that are of the same magnitude (22.0 ± 0.3 μM, 17.4 ± 0.4 μM, and 17.8 ± 0.4 μM for human, mouse, and rat ACE2, respectively). However, the Ki for human ACE2 is lower (0.040 ± 0.005 μM) than for mouse and rat ACE2 (0.36 ± 0.03 μM and 0.49 ± 0.06 μM, respectively). Under these conditions, the IC50 for human ACE2 with 50 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) is ∼0.08 μM, while the IC50 for rodent ACE2 is ∼1.3 μM. At 10 μM Mca-APK(Dnp), the IC50 for rodent ACE2 is further reduced to around 0.7 μM. We conclude that DX600 has higher affinity for human than for rodent ACE2.

Fig. 5.

Determination of kinetic parameters. One of four independent data sets used for determining the Michealis constant Km and the dissociation constant Ki between DX600 and mouse ACE2 is shown. The hydrolytic activity of a cell extract of 832/13 cells transfected with the mouse ACE2 expression plasmid was measured at different concentrations of DX600 and Mca-APK(Dnp). Kinetic parameters, including Km and Ki, were fitted to a model of mixed-type enzyme inhibition by nonlinear regression. The curves are generated with the best-fit values of the kinetic parameters, including Km = 16.6 μM and Ki = 0.31 μM for this data set.

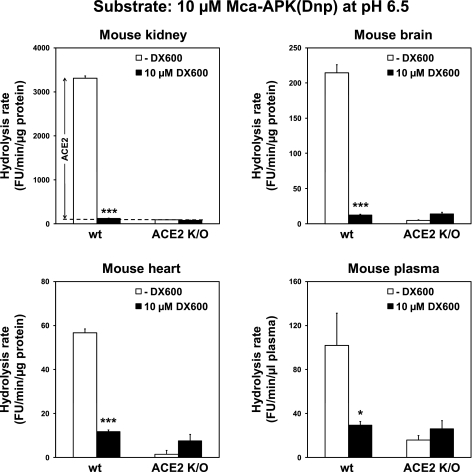

We finally assessed whether the optimized assay conditions with 10 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) and 10 μM DX600 at pH 6.5 were applicable for detecting endogenous ACE2 in mouse tissues. We analyzed kidney, brain, heart, and plasma from wild-type and ACE2 knockout mice. For the kidney, 99% of the estimated true ACE2 activity was detected by the optimized method (Fig. 6). The estimated ratio between ACE2 and non-ACE2 enzymes hydrolyzing the fluorogenic substrate is also better in the optimized method (37-fold vs. 3.7-fold for results shown in Fig. 2C). The optimized method likewise detects ACE2 in mouse brain, heart, and plasma with strong inhibition (98%, 86%, and 90% of the estimated true ACE2 activities, respectively) by 10 μM DX600 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

An optimized method allows robust detection of endogenous ACE2 in mouse tissues. Hydrolysis rates of 10 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) at pH 6.5 for wild-type (wt) and ACE2 knockout (K/O) mouse kidney, brain, heart, and plasma were measured in the absence and presence of 10 μM DX600. The stippled line indicates the average hydrolytic activity of knockout mice kidneys in the presence and absence of DX600, which is a parameter for hydrolysis of Mca-APK(Dnp) by non-ACE2 enzymes. This parameter is used to calculate the estimated true ACE2 activity in wild-type mouse kidneys. *Significant difference, P < 0.05. ***Significant difference, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that mouse and rat ACE2 are less sensitive to inhibition by DX600 than human ACE2. Amino acid residues 149 and 368 at the active site of ACE2 did not explain the species-specific effects. These amino acid differences between human and rodent ACE2 also seem to have only minor effects on Km values toward the fluorogenic substrate Mca-APK(Dnp). Rather, the diminished DX600 sensitivity of rodent ACE2 is likely due to some of the other 87 amino acid residues that are shared in rat and mouse ACE2 but different in human ACE2. This is consistent with DX600 being a mixed-type enzyme inhibitor (16), as such an inhibitor can bind to and inhibit both the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex.

In an assay for measuring human ACE2 expressed in mouse tissues, ACE2 activity was previously determined in our laboratory as the difference in hydrolysis rate of Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp) in the absence and presence of 1 μM DX600 (1, 10). As there is only minimal inhibition of mouse ACE2 under these conditions (Fig. 2), the endogenous mouse ACE2 activity will have been underestimated relative to the activity from the human ACE2 transgene, and the ratio of human ACE2 to endogenous murine ACE2 would consequently have been overestimated.

In contrast to our work, other groups have reported near-complete inhibition of mouse and rat ACE2 activity at DX600 concentrations of 1 μM or lower (12, 19). However, despite our attempts, we have not been able to reproduce these data and effectively inhibit rodent ACE2 with 1 μM DX600, suggesting that additional divergences in experimental conditions may contribute to these differences. Mouse and rat ACE2 activities have been assessed by other researchers in assays with 100 μM of DX600 (17, 18). Although no data were provided showing the degree of inhibition of rodent ACE2, we observed that 100 μM DX600 inhibits at least 90% of the activity of rodent ACE2 expressed in cell lines (Fig. 3 and data not shown). Because of the high cost of DX600, we attempted to establish a protocol with 10 μM DX600 applicable for measuring rodent ACE2. An optimized method with 10 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) at pH 6.5 robustly allows measurement of rodent ACE2 expressed in 832/13 cells, as well as of ACE2 in mouse tissues (Figs. 4 and 6). The change in pH from 7.5 to 6.5 is crucial for ensuring effective inhibition by DX600 (Fig. 4B). It further increases the hydrolysis rate of the substrate (Fig. 4A), as was previously observed for a soluble form of human ACE2 (28). A mouse renal ACE2 activity assay based on inhibition with MLN-4760 was likewise highly dependent on the pH (20). Lowering the concentration of the ACE2 substrate Mca-APK(Dnp) from 50 μM to 10 μM also contributes to increased DX600 sensitivity, as evidenced by a reduction of IC50. Yet, determinations of Ki and IC50 values show that even at pH 6.5, human ACE2 is more sensitive to inhibition by DX600 than rodent ACE2.

DX600 is a 26-amino acid peptide (16). The manufacturer notes in a specification sheet that DX600 contains two free cysteine residues and tends to polymerize. Polymerization and oxidation of DX600 might conceivably affect binding to and inhibition of ACE2. Therefore, the manufacturer recommends dissolving DX600 just before use. Accordingly, we only used DX600 that was hydrated the same day that ACE2 assays were conducted. ACE2 does not hydrolyze DX600 (16), but it may be susceptible to cleavage by other proteases or peptidases. Some hydrolysis of DX600 may, therefore, occur at the ACE2 activity assay conditions, but with an initial concentration of 10 μM DX600, there must obviously have been a sufficient amount of DX600 present to inactivate rodent ACE2 in the cell and tissue extracts employed in our study.

DX600 has been used to treat rodents in vivo (13, 19). Inhibition of ACE2 activity in vivo will be determined by the local concentration of DX600 in the tissues relative to the in vivo binding affinity between DX600 and native ACE2. Angiotensin substrates for ACE2 in vivo seem to be hydrolyzed at much lower concentrations than the Km values for ANG I and ANG II, which, in vitro, have been determined to be ≥2 μM (16, 25, 28). For example, rat plasma and renal interstitial fluid contain less than 10 nM ANG I and ANG II (21). Under such conditions, the IC50 in vivo would be approximately equal to the Ki (2). To our knowledge, no study of the tissue concentration of DX600 or the affinity between DX600 and ACE2 in vivo following DX600 treatment has been reported. A direct measurement of ACE2 activity in a thrombus after DX600 administration has been carried out, but the decrease in ACE2 activity was not statistically significant (13). Thus, while the physiological effects of DX600 may be due to inhibition of ACE2, it is also possible that DX600 has off-target effects on the animals.

In summary, mouse and rat ACE2 activity can reliably be determined as the difference in hydrolysis rate of 10 μM Mca-APK(Dnp) at pH 6.5 in the absence and presence of 10 μM DX600.

Perspectives and Significance

ACE2 has been recognized as a critical component of the renin-angiotensin system, capable of modulating the deleterious effects of the ACE/ANG II/AT1 receptor axis (3, 31). Measurement of ACE2 activity is the more reliable index to assess the compensatory role of this enzyme in health and disease. Therefore, an accurate estimate of ACE2 activity and knowledge of species differences are necessary. Our work provides a reliable way of measuring rodent ACE2 activity using the commercially available inhibitor DX600. It further stresses the importance of validating the effect of DX600 on ACE2 from each particular species at the experimental conditions employed.

GRANTS

The work was supported by the grants National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK084466 and NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute HL093178 to E. Lazartigues.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Christopher B. Newgard, Duke University Medical Center for the 832/13 cell line, Dr. Curt D. Sigmund, University of Iowa for the expression plasmid for human ACE2, and Susan Gurley and Tom Coffman, Duke University and Durham VA Medical Centers for the ACE2 knockout mice.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bindom SM, Hans CP, Xia H, Boulares H, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme type 2 (ACE2) gene therapy improves glycemic control in diabetic mice. Diabetes 59: 2540–2548, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blat Y. Non-competitive inhibition by active site binders. Chem Biol Drug Des 75: 535–540, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chhabra K, Pedersen KB, Lazartigues E. Renin-angiotensin system and diabetes. In: Beta Cells: Functions, Pathology and Research, edited by Gallagher SE. Hauppauge, NY: NOVA Publishers, 2011, p. 151–163 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dales NA, Gould AE, Brown JA, Calderwood EF, Guan B, Minor CA, Gavin JM, Hales P, Kaushik VK, Stewart M, Tummino PJ, Vickers CS, Ocain TD, Patane MA. Substrate-based design of the first class of angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc 124: 11852–11853, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diez-Freire C, Vazquez J, Correa de Adjounian MF, Ferrari MFR, Yuan L, Silver X, Torres R, Raizada MK. ACE2 gene transfer attenuates hypertension-linked pathophysiological changes in the SHR. Physiol Genomics 27: 12–19, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N, Donovan M, Woolf B, Robison K, Jeyaseelan R, Breitbart RE, Acton S. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1–9. Circ Res 87: e1–e9, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doobay MF, Talman LS, Obr TD, Tian X, Davisson RL, Lazartigues E. Differential expression of neuronal ACE2 in transgenic mice with overexpression of the brain renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R373–R381, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Douglas GC, O'Bryan MK, Hedger MP, Lee DKL, Yarski MA, Smith AI, Lew RA. The novel angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) homolog, ACE2, is selectively expressed by adult Leydig cells of the testis. Endocrinology 145: 4703–4711, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Enari M, Talanian RV, Wrong WW, Nagata S. Sequential activation of ICE-like and CPP32-like proteases during Fas-mediated apoptosis. Nature 380: 723–726, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feng Y, Xia H, Cai Y, Halabi CM, Becker LK, Santos RAS, Speth RC, Sigmund CD, Lazartigues E. Brain-selective overexpression of human angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 attenuates neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res 106: 373–382, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feng Y, Yue X, Xia H, Bindom SM, Hickman PJ, Filipeanu CM, Wu G, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 overexpression in the subfornical organ prevents the angiotensin II-mediated pressor and drinking responses and is associated with angiotensin II type 1 receptor downregulation. Circ Res 102: 729–736, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fernandes T, Hashimoto NY, Oliveira EM. Characterization of angiotensin-converting enzymes 1 and 2 in the soleus and plantaris muscles of rats. Braz J Med Biol Res 43: 837–842, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fraga-Silva RA, Sorg BS, Wankhede M, deDeugd C, Jun JY, Baker MB, Li Y, Castellano RK, Katovich MJ, Raizada MK, Ferreira AJ. ACE2 activation promotes antithrombotic activity. Mol Med 16: 210–215, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gurley SB, Allred A, Le TH, Griffiths R, Mao L, Philip N, Haystead TA, Donoghue M, Breitbart RE, Acton SL, Rockman HA, Coffman TM. Altered blood pressure responses and normal cardiac phenotype in ACE2-null mice. J Clin Invest 116: 2218–2225, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, Newgard CB. Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 49: 424–430, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang L, Sexton DJ, Skogerson K, Devlin M, Smith R, Sanyal I, Parry T, Kent R, Enright J, Wu Ql Conley G, DeOliveira D, Morganelli L, Ducar M, Wescott CR, Ladner RC. Novel peptide inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J Biol Chem 278: 15532–15540, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huentelman MJ, Grobe JL, Vazquez J, Stewart JM, Mecca AP, Katovich MJ, Ferrario CM, Raizada MK. Protection from angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis by systemic lentiviral delivery of ACE2 in rats. Exp Physiol 90: 783–790, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huentelman MJ, Zubcevic J, Katovich MJ, Raizada MK. Cloning and characterization of a secreted form of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Regul Pept 122: 61–67, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li X, Molina-Molina M, Abdul-Hafez A, Uhal V, Xaubet A, Uhal BD. Angiotensin converting enzyme-2 is protective but downregulated in human and experimental lung fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L178–L185, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu J, Ji H, Zheng W, Wu X, Zhu JJ, Arnold AP, Sandberg K. Sex differences in renal angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) activity are 17β-oestradiol-dependent and sex chromosome-independent. Biol Sex Differ 1: 6, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nishiyama A, Seth DM, Navar LG. Renal interstitial fluid angiotensin I and angiotensin II concentrations during local angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2207–2212, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pedersen KB, Buckley RS, Scioneaux R. Glucose induces expression of rat pyruvate carboxylase through a carbohydrate response element in the distal gene promoter. Biochem J 426: 159–170, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pedersen KB, Zhang P, Doumen C, Charbonnet M, Lu D, Newgard CB, Haycock JW, Lange AJ, Scott DK. The promoter for the gene encoding the catalytic subunit of rat glucose-6-phosphatase contains two distinct glucose-responsive regions. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E788–E801, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Prieto MC, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Botros FT, Martin VL, Pagan J, Satou R, Lara LS, Feng Y, Fernandes FB, Kobori H, Casarini DE, Navar LG. Reciprocal changes in renal ACE/ANG II and ACE2/ANG 1–7 are associated with enhanced collecting duct renin in Goldblatt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F749–F755, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rice GI, Thomas DA, Grant PJ, Turner AJ, Hooper NM. Evaluation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), its homologue ACE2 and neprilysin in angiotensin peptide metabolism. Biochem J 383: 45–51, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, Karran E, Christie G, Turner AJ. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem 275: 33238–33243, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Towler P, Staker B, Prasad SG, Menon S, Tang J, Parsons T, Ryan D, Fisher M, Williams D, Dales NA, Patane MA, Pantoliano MW. ACE2 X-ray structures reveal a large hinge-bending motion important for inhibitor binding and catalysis. J Biol Chem 279: 17996–18007, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vickers C, Hales P, Kaushik V, Dick L, Gavin J, Tang J, Godbout K, Parsons T, Baronas E, Hsieh F, Acton S, Patane M, Nichols A, Tummino P. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem 277: 14838–14843, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wysocki J, Ye M, Soler MJ, Gurley SB, Xiao HD, Bernstein KE, Coffman TM, Chen S, Batlle D. ACE and ACE2 activity in diabetic mice. Diabetes 55: 2132–2139, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xia H, Feng Y, Obr TD, Hickman PJ, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor-mediated reduction of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity in the brain impairs baroreflex function in hypertensive mice. Hypertension 53: 210–216, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xu P, Sriramula S, Lazartigues E. ACE2/ANG-(1–7)/Mas pathway in the brain: the axis of good. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R804–R817, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang R, Smolders I, Dupont AG. Blood pressure and renal hemodynamic effects of angiotensin fragments. Hypertens Res 34: 674–683, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]