Abstract

We previously reported that mild deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt hypertension develops in the absence of generalized sympathoexcitation. However, sympathetic nervous system activity (SNA) is regionally heterogeneous, so we began to investigate the role of sympathetic nerves to specific regions. Our first study on that possibility revealed no contribution of renal nerves to hypertension development. The splanchnic sympathetic nerves are implicated in blood pressure (BP) regulation because splanchnic denervation effectively lowers BP in human hypertension. Here we tested the hypothesis that splanchnic SNA contributes to the development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension. Splanchnic denervation was achieved by celiac ganglionectomy (CGX) in one group of rats while another group underwent sham surgery (SHAM-GX). After DOCA treatment (50 mg/kg) in rats with both kidneys intact, CGX rats exhibited a significantly attenuated increase in BP compared with SHAM-GX rats (15.6 ± 2.2 vs. 25.6 ± 2.2 mmHg, day 28 after DOCA treatment). In other rats, whole body norepinephrine (NE) spillover, measured to determine if CGX attenuated hypertension development by reducing global SNA, was not found to be different between SHAM-GX and CGX rats. In a third group, nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover was measured as an index of splanchnic SNA, but this was not different between SHAM (non-DOCA-treated) and DOCA rats during hypertension development. In a final group, CGX effectively abolished nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover. These data suggest that an intact splanchnic innervation is necessary for mild DOCA-salt hypertension development but not increased splanchnic SNA or NE release. Increased splanchnic vascular reactivity to NE during DOCA-salt treatment is one possible explanation.

Keywords: regional sympathetic activity, celiac ganglionectomy, nonhepatic splanchnic norepinephrine spillover, whole body norepinephrine spillover, deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt

increased sympathetic outflow to peripheral organs is linked to hypertension development (18). Mineralocorticoids have recently been shown to play a larger role in human hypertension than previously appreciated (21), and new evidence suggests that one mechanism is increased sympathetic nervous system activity (SNA) (36). The most commonly studied experimental model of mineralocorticoid hypertension is created by treating uninephrectomized rats with deoxycorticosterone acetate and salt (DOCA-salt rats). There is evidence both for (4, 10, 20) and against (49) increased SNA as a cause of hypertension in DOCA-salt rats. A complication of this model is that the animals become severely hypertensive and develop marked end organ damage over just several weeks' time. In a previous study, we sought to determine the contribution of SNA to mineralocorticoid hypertension in rats using a modified DOCA-salt model (30). Animals were not subjected to uninephrectomy and were given a lower dose of DOCA. Hypertension development was more gradual, and the final increase in arterial pressure (AP) was only 20–30 mmHg. We have termed this “mild” DOCA-salt hypertension. There were two main reasons for choosing this model over the traditional DOCA-salt hypertension model. First, the magnitude of increase in blood pressure (BP) was modest and more comparable to that observed in the majority of human hypertensive subjects. Second, a smaller and slower increase in BP would be less likely to cause the end organ damage and thus allow us to more readily identify mechanisms that primarily serve as factors causing hypertension rather than those that are consequences of high BP. Our initial findings were that generalized (or global) SNA, measured using whole body norepinephrine (NE) spillover, is not increased during the development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension (30). However, in light of evidence that regionally specific changes in SNA are sufficient to produce hypertension (18, 60), we investigated the influence of renal SNA in the model using renal denervation. We concluded that fully intact renal nerves are not essential for mild DOCA-salt hypertension development, since renal denervation failed to affect the development of hypertension (31).

Previous work from our laboratory has highlighted the importance of vascular capacitance in the pathophysiology of DOCA-salt hypertension (20). This function is largely invested in the venous side of the circulation, particularly in the veins draining the splanchnic organs (20, 57). About 25% of the total blood volume is contained in the highly compliant splanchnic vasculature (35, 50). Splanchnic organs receive most of their sympathetic input from the celiac ganglion plexus (CG), formed by the celiac and superior mesenteric ganglia (26, 54). In the late 1940s and early 1950s, surgical removal of celiac ganglion plexus (celiac ganglionectomy, CGX) performed in humans proved beneficial in attenuating essential hypertension (22, 23). Those findings emphasize the importance of splanchnic SNA in human hypertension. A recent study performed in the ANG II-salt model of experimental hypertension in rats also demonstrated that CGX significantly attenuates hypertension development (35). To investigate a possible role of the splanchnic SNA in the development and maintenance of hypertension in our mild DOCA-salt model, we performed a series of experiments involving CGX and regional and whole body NE spillover measurements. We hypothesized that splanchnic SNA is increased in this model and that CGX would attenuate hypertension development and/or maintenance.

METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats (225–275 g) were used in the experiments. All protocols were approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. After arrival, rats were acclimatized for 7 days under controlled temperature and humidity conditions with an alternate 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Rats were allowed free access to water and food.

Mild DOCA-Salt Hypertension

Under isoflurane anesthesia, a DOCA pellet (50 mg/kg) was implanted subcutaneously in one group of rats (DOCA) while the other group (SHAM) underwent sham implantation surgery with both kidneys intact. Both groups received water containing 1% NaCl and 0.2% KCl.

CGX and Radiotelemeter Implantation

Laparotomy was performed under isoflurane anesthesia by a ventral midline incision. After the abdomen was exposed, intestines were retracted to visualize the CG and soaked with warm saline gauze for the entire duration of surgery. The CG was then dissected and removed. Intestines were placed back in the abdominal cavity and lavaged with warm saline. Next, the body of a radiotelemeter was placed in the abdomen, and the attached catheter was tunneled subcutaneously to the groin. The tip of the catheter was then placed in the abdominal aorta through the femoral artery. SHAM-GX surgery was performed by visualizing the CG after laparotomy. After CGX and SHAM-GX, the incision was closed in layers.

Confirmation of Denervation

Rats were euthanized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) at the end of the experiment. The spleen and kidneys, and sections of small intestine and liver, were harvested from each animal, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for later analysis. Tissue NE content of the samples was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis with electrochemical detection. Data are reported as nanograms of NE per gram of tissue.

Catheterization

Femoral vessels.

Catheters were implanted in the abdominal aorta and vena cava under 2% isoflurane anesthesia as described previously (20, 34). Rats were allowed to recover for 7 days and had free access to water and food. Catheters were flushed and refilled every day with heparin-saline (100 U/ml). Antimicrobial prophylaxis was achieved by ticarcillin-clavulanate (200 mg/kg ip) and enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg ip) administered daily for the entire duration of the experiment. Postsurgical analgesia was achieved by carprofen (5 mg/kg sc). Meloxicam (1 mg/kg po) was administered daily for three additional days after surgery.

Portal vein.

For measuring nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover, an additional catheter was placed in the portal vein for sampling splanchnic venous drainage. During the same surgery as for femoral catheterization, a ventral midline incision was made to expose the abdominal cavity. Intestines were retracted to the side to visualize the portal vein. A small branch going into the portal vein was carefully dissected free of connective tissue. A silicone catheter with inner diameter 0.020 in. and outer diameter 0.037 in. (Dow Corning) was placed in the portal vein through this branch such that the tip of the catheter was close to the entry of the portal vein into the liver, without obstructing portal blood flow. The catheter was then tunneled subcutaneously into the back and exteriorized at the neck along with the femoral catheters to be tethered for chronic blood sampling. The abdominal incision was closed in layers.

Hemodynamic Measurements

Whole body and regional NE spillover studies.

Hemodynamic measurements were made using previously established methods in our laboratory (20, 34). Briefly, AP was measured by connecting the arterial catheter to a pressure transducer (TDX-300; Micro-Med) that senses changes in AP and relays signals to a digital pressure analyzer (BPA-400; Micro-Med) through a pressure transducer. Mean arterial pressure (MAP), systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, and heart rate (HR) were sampled at a rate of 1,000 Hz. The pressure analyzer was linked to a computer where the data were analyzed by data acquisition software (DMSI-400; Micro-Med). The pressure transducers were calibrated at the beginning of the experiment using a sphygmomanometer and balanced daily against a water column located at the level of the rat's heart. AP and HR were measured daily for 1 h and recorded as 1-min averages.

CGX.

In one study, AP and HR were measured using telemetry. A radiotelemeter (TA11PA-C40; Data Sciences International) transmitted signals to an external receiver (RPC-1; Data Sciences International) that then relayed signals to a computerized data acquisition program (Dataquest ART 3.1; DSI). Hemodynamic measurements were sampled at 500 Hz, 24 h a day, with a scheduled sampling interval of 10 s every 10 min for the entire duration of the experiment. Data are reported as 24-h averages.

Whole Body NE Spillover

Whole body NE clearance and spillover were measured by an established method described previously by King et al. (34). Briefly, tracer amounts of Levo-[ring-2,5,6-3H]NE (Perkin-Elmer) were infused intravenously at 0.13 μCi·min−1·kg−1 at the rate of 16 μl/min for 90 min to produce a steady-state plasma concentration of [3H]NE. One milliliter of blood was collected from the arterial catheter after the infusion, and the plasma was stored at −80°C after centrifugation. Plasma NE concentration was determined by batch alumina extraction followed by separation using high-performance reversed-phase liquid chromatography with coulometric detection (ESA Biosciences). Quantification was accomplished using a modified method originally reported by Holmes et al. (25). After chromatographic analysis, the NE fraction was collected and [3H]NE was quantified by liquid scintillation counting. Whole body NE clearance and spillover were calculated using the following formulas (32):

Nonhepatic Splanchnic NE Spillover

Regional NE spillover was measured by a previously described method (17). Similar to the whole body NE spillover technique, tracer amounts of Levo-[ring-2,5,6-3H]NE (Perkin-Elmer) were infused intravenously at 0.13 μCi·min−1·kg−1 at the rate of 16 μl/min for 90 min to produce a steady-state plasma concentration of [3H]NE. One milliliter of arterial and portal venous blood was drawn simultaneously from the respective catheters, and the plasma was stored at −80°C until further analysis. Plasma NE and [3H]NE concentrations were calculated as described above. Nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover rate can be derived by measuring radiolabeled and endogenous NE concentrations in the arterial and portal venous plasma, and the portal venous plasma flow. Because of technical difficulties, we were unable to measure portal blood flow in the same rats with portal vein catheters. For this reason, we assumed constant plasma flow in DOCA and SHAM rats. This assumption is supported by several studies showing that blood flow to splanchnic organs in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats is generally not different from that of SHAM animals (51, 58). The value of portal venous plasma flow was obtained from a previous study performed in our laboratory using flow probes chronically implanted around the portal vein in conscious rats (n = 4) weighing 350–375 g at the time of flow measurement (10.1 ± 0.8 ml/min, unpublished observations). Nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover was calculated using the following formulas:

NEA is arterial plasma NE concentration, NEV is portal venous plasma NE concentration, PF is plasma flow in the portal vein, FX is the fractional extraction of NE during its passage through the splanchnic bed, [3H]NEA is arterial [3H]NE concentration, and [3H]NEv is portal venous [3H]NE concentration.

Experimental Protocols

CGX and DOCA-salt hypertension.

AP and HR recordings were started after a 7-day postsurgical recovery period. After 5 days of control recordings, rats were allowed free access to water containing 1% NaCl and 0.2% KCl for the entire duration of the experiment. After a 7-day period of salt treatment, a DOCA pellet (50 mg/kg sc) was implanted in both CGX and SHAM-GX groups, and BP was recorded for four more weeks. Twenty four-hour saline intake was also measured for 2 days at the end of the experiment before the rats were euthanized for harvesting splanchnic organs to measure tissue NE content.

Effect of CGX on whole body NE spillover.

To study the effect of CGX on whole body NE spillover, some rats underwent CGX while the others had SHAM-GX surgery. These groups were treated essentially the same as rats in the previous protocol except that they had externalized catheters instead of a radiotelemeter. After a 7-day recovery period, catheters were implanted to measure whole body NE spillover as described above. Five days after catheter implantation, control hemodynamic measurements were made for 3 days followed by a subcutaneous DOCA pellet implant in both groups. AP and HR were measured around 10:00 A.M. every day for 1 h for another 14 days. Whole body NE spillover was measured on control day 2 and days 7 and 14 following DOCA treatment.

Nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover.

Catheters were implanted in the femoral artery and vein and the portal vein for BP measurement, chronic infusion, and sampling purposes. After a 7-day recovery period, control hemodynamic measurements were made for 3 days. A DOCA pellet was then implanted subcutaneously to induce hypertension development. AP and HR were measured for another three weeks. Nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover was measured on control day 2 and days 7, 14, and 21 following DOCA treatment.

Effect of CGX on nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover.

CGX surgery was performed on a group of rats, and catheters were implanted to measure nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover. Rats were allowed to recover for 10 days. Hemodynamic measurements were made for 3 days following recovery. Nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover was then measured in all rats.

Statistical Analyses

Within-group hemodynamic differences were assessed by repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple-comparisons test. Between-group hemodynamic differences were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test. Plasma NE concentration, NE clearance, and NE spillover were analyzed by paired t-test. The effect of splanchnic denervation on nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover was calculated using one-tailed t-test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Effect of CGX on DOCA-Salt Hypertension

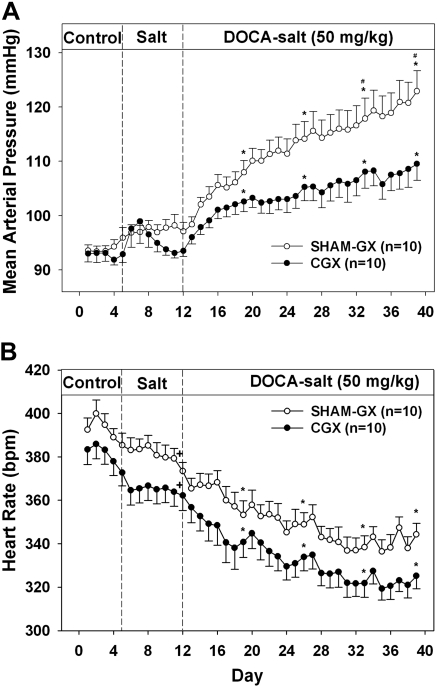

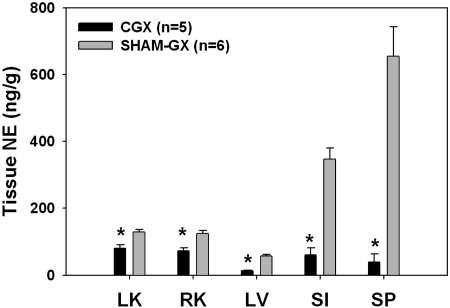

MAP and HR during the development of DOCA-salt hypertension in CGX and SHAM-GX rats are shown in Fig. 1. There was no difference in MAP between CGX and SHAM-GX rats during the control period. Increased salt intake alone did not change MAP significantly in either CGX or SHAM-GX groups. Upon DOCA administration, an increase in MAP was seen in both groups of rats, but this increase was attenuated significantly in CGX compared with the SHAM-GX group [15.6 ± 2.2 vs. 25.6 ± 2.2 mmHg at day 40 of the protocol (28 days after starting DOCA treatment)]. HR was significantly lower in both CGX and SHAM-GX groups during high salt intake and during DOCA treatment compared with their respective control period values, but the change in HR between the two groups was not significantly different at any time during the experiment. NE contents of splanchnic organs measured at the end of the experiment are shown in Fig. 2. NE content in the CGX group compared with the SHAM-GX group was less by 30–40% in the kidneys, 81% in liver, 67% in small intestine, and by 94% in the spleen. Consumption of saline drinking fluid, measured at the end of the experiment, was not different between the two groups (SHAM-GX 140.4 ± 22.8 and CGX 140.0 ± 29.1 ml/day).

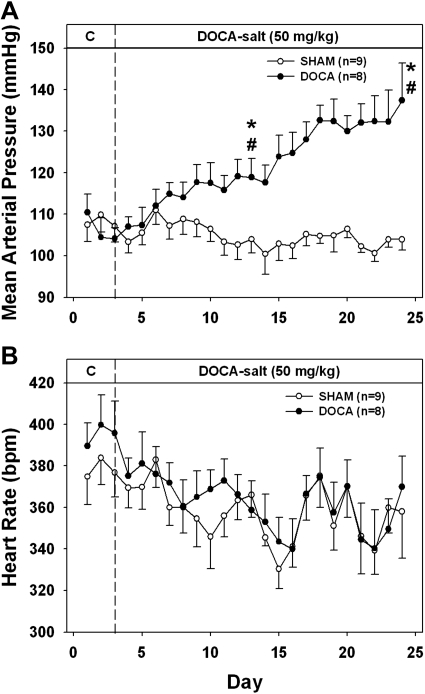

Fig. 1.

Mean arterial pressure (A) and heart rate (B) during the control, high-salt, and deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) treatment periods in SHAM-GX (sham operated) and celiac ganglionectomy (CGX) groups. bpm, Beats/min. *Significant difference from day 3 (control period) values. #Difference between the two groups.

Fig. 2.

Tissue norepinephrine (NE) content in the splanchnic organs after 4 wk of DOCA administration. LK, left kidney; RK, right kidney; LV, liver; SI, small intestine; SP, spleen. *Significant difference between the two groups.

Effect of CGX on Whole Body NE Spillover in DOCA-Salt Hypertension

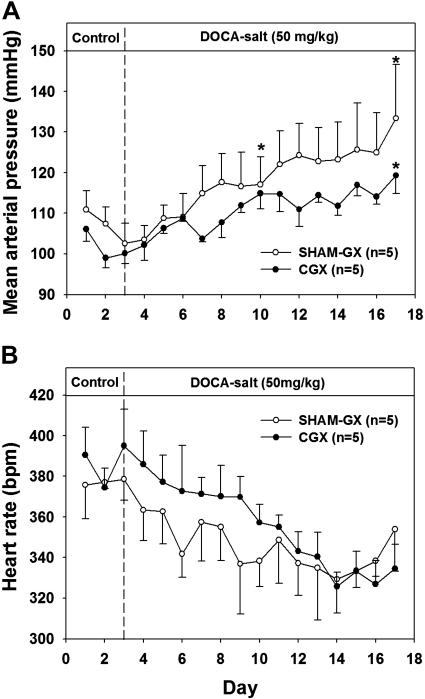

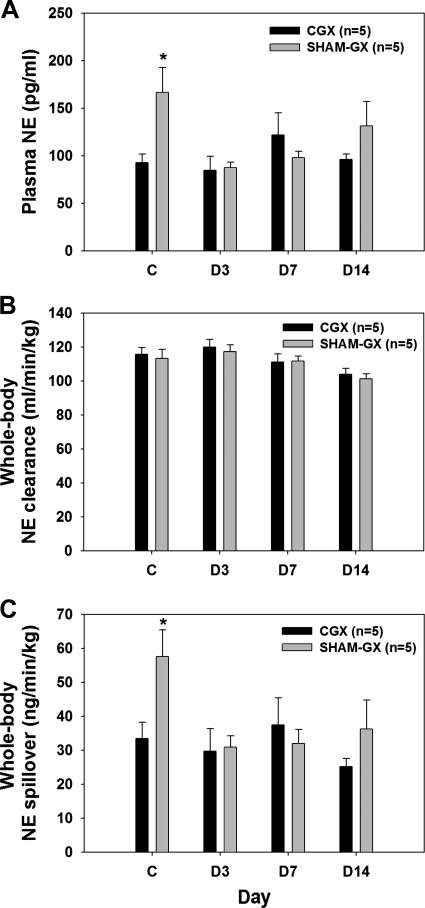

Figure 3 shows MAP and HR during the development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension in CGX and SHAM-GX animals. During the control period, MAP was slightly lower in CGX than SHAM-GX rats, but the difference was not significant. After DOCA administration, both groups became hypertensive, but the increase in MAP was attenuated in the CGX group (Fig. 3A). However, the final absolute MAP was not statistically different between the two groups. No significant difference was observed in HR between the two groups (Fig. 3B). During the control period, whole body plasma NE (Fig. 4A) and whole body NE spillover (Fig. 4C) were significantly higher in SHAM-GX rats compared with CGX animals but otherwise were similar in both groups on days 3, 7, and 14 of DOCA treatment. NE clearance was not different in the two groups on control day 2 or on days 3, 7, and 14 of DOCA treatment (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3.

Mean arterial pressure (A) and heart rate (B) during the control and DOCA treatment periods in SHAM-GX and CGX groups. *Significant difference from day 3 (control period) values.

Fig. 4.

Plasma NE (A), whole body NE clearance (B), and NE spillover (C) in SHAM-GX and CGX on control day 2 (C) and days (D) 3, 7, and 14 after DOCA treatment. *Significant difference between the groups during the control period.

Nonhepatic Splanchnic NE Spillover

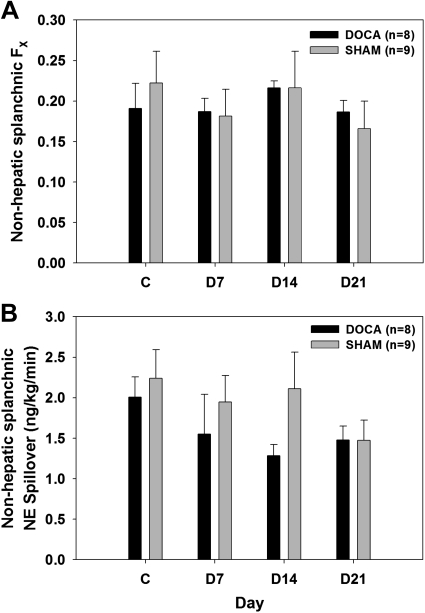

MAP was similar in DOCA and SHAM rats during the control period. DOCA rats became significantly hypertensive during DOCA treatment while the SHAM rats remained normotensive throughout the experimental period (Fig. 5A). There were no differences in HR between the two groups at any time during the experimental period (Fig. 5B). Arterial and portal venous plasma NE concentrations were not different at any time in DOCA vs. SHAM rats (Fig. 6). Fractional extraction of NE by the nonhepatic splanchnic organs was also similar in both groups (Fig. 7A). Hence, estimated nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover was not different at any time in DOCA vs. SHAM rats (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 5.

Mean arterial pressure (A) and heart rate (B) during the control and DOCA treatment periods in DOCA and SHAM rats. *Significant difference from day 3 (control period) values. #Difference between the two groups.

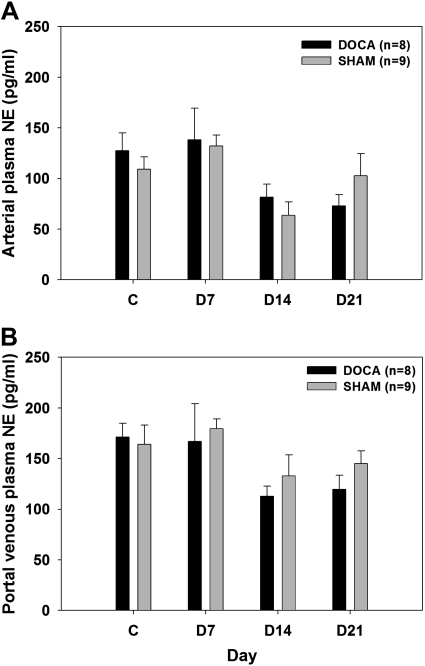

Fig. 6.

Arterial (A) and portal venous (B) plasma NE concentration in DOCA and SHAM rats on control day 2 and days 7, 14, and 21 after DOCA treatment.

Fig. 7.

Fractional extraction of NE (FX, A) and nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover (B) in DOCA and SHAM rats on control day 2 and days 7, 14, and 21 after DOCA treatment.

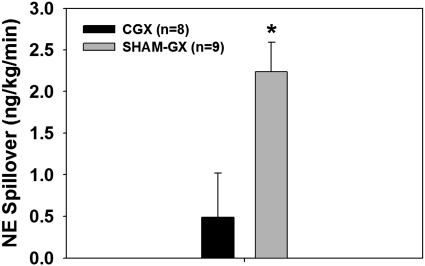

Effect of CGX on Nonhepatic Splanchnic NE Spillover

After CGX, MAP was 110.1 ± 1.7 mmHg. This value was similar to the MAP measured in the SHAM group (109.9 ± 4.2 mmHg) from the previous study. Nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover after CGX was 0.5 ± 0.53 ng·min−1·kg−1 (Fig. 8), a value not significantly different from zero (one-tailed “t” test). CGX also significantly attenuated NE spillover in the splanchnic region compared with values measured in SHAM rats during the control period of the previous study (2.24 ± 0.35 ng·min−1·kg−1; Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover in CGX and SHAM-GX rats. *Value is not significantly different from 0.

DISCUSSION

The main new findings of this study on the role of regional SNA in the development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension are: 1) splanchnic sympathetic denervation by CGX attenuates hypertension development, 2) whole body NE spillover does not reflect changes in splanchnic NE spillover and cannot be used to assess splanchnic SNA, and 3) elevated splanchnic SNA assessed by nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover is not required for the development of hypertension.

Effect of CGX on Splanchnic Sympathetic Innervation

A decrease in splanchnic tissue NE content even 7 wk after CGX provided confirmation that denervation was achieved successfully (Fig. 2). NE content in the splanchnic organs was significantly reduced, with splenic content affected the most (by 94%). This is consistent with previous findings showing an ∼85% reduction in splenic NE content (3, 37) after CGX or selective denervation of the spleen. Previous reports indicate that sympathetic postganglionic nerves show regeneration after chemical or surgical sympathectomy (24, 37). This regeneration of postganglionic neurons can reestablish neuroeffector transmission at the nerve terminal. However, regeneration does not appear to be substantial because NE content of splanchnic organs was still very low at the end of study, and BP was attenuated throughout the experimental period in CGX rats. There was a 30–40% reduction in NE content in the kidneys. This is not surprising because 20–25% of the postganglionic neurons supplying the kidneys originate in the celiac ganglion while the majority (∼80%) come from the paravertebral sympathetic chain (7, 19, 52). However, as demonstrated previously (31), fully intact renal nerves are not essential for hypertension development in this model. Thus, any effects of CGX on AP in our model are likely the result of sympathetic denervation of nonrenal splanchnic organs.

Effect of CGX on Hypertension Development

The rise in BP after DOCA administration was attenuated significantly in CGX rats compared with that of SHAM-GX rats. This suggests that an intact splanchnic sympathetic innervation is necessary for the full development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension, but additional studies were necessary to elucidate the mechanism of this effect.

Effect of CGX on Whole Body NE Spillover

The finding that splanchnic sympathectomy with CGX impairs hypertension development was surprising because, in earlier studies, we found no evidence for increased whole body SNA during the development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension. However, splanchnic SNA may not be reflected in whole body assessments of sympathetic activity. This might seem unlikely since one study reported that a large fraction (∼37%) of total sympathetic outflow is directed toward splanchnic organs (2). However, NE released in the blood from the splanchnic bed must pass through the liver before reaching the systemic circulation, and the vast majority (∼86%) is extracted there. Thus, nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover is obscured when using standard methods of measuring whole body NE spillover (2). To investigate whether splanchnic denervation attenuates hypertension development by decreasing generalized sympathetic activity, we measured plasma NE levels and whole body NE spillover in CGX animals during the development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension.

During the control period, plasma NE and whole body NE spillover were in fact significantly lower in CGX vs. SHAM-GX rats (Fig. 4, A and C). On the surface, this finding appears to support the conclusion that CGX causes a measurable decrease in global SNA assessed from whole body NE spillover or plasma NE levels. However, both measures were comparable in CGX and SHAM-GX rats throughout the remainder of the study. Furthermore, plasma NE and whole body NE spillover in the SHAM-GX rats during the control period in this study were markedly higher than we measured previously (30, 31). We concluded that the higher values of plasma NE and whole body NE spillover in SHAM-GX rats during the control period were most likely aberrant because of specific conditions during the blood sampling at that time. One likely possibility is that fluctuations in plasma catecholamines can occur by noise-induced stress in otherwise undisturbed rats (9). Most important for our main hypothesis was the finding of no changes in plasma NE or whole body NE spillover in CGX rats on days 3, 7, and 14 after DOCA treatment. Overall, we conclude that the effects of CGX on splanchnic SNA are not revealed by measurements of plasma NE levels or whole body NE spillover and that CGX does not attenuate hypertension development by decreasing generalized sympathetic activity.

Nonhepatic Splanchnic NE Spillover

To address the possibility that splanchnic SNA is elevated in mild DOCA-salt hypertension development without being reflected in plasma NE levels or whole body NE spillover measurements, we used the radioisotope dilution technique to estimate the rate of NE release from nonhepatic splanchnic organs (i.e., nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover) as an index of splanchnic SNA. We also studied the effect of splanchnic denervation (via CGX) on nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover. Sampling of portal venous blood is ideal and provides a direct estimate of the amount of NE released by nonhepatic splanchnic organs before it enters the liver. Nonhepatic splanchnic NE measurements have been reported in anesthetized human patients and in some anesthetized and conscious experimental animals (1, 2, 8, 27). This is the first study to report nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover in conscious, undisturbed rats.

Effect of CGX on Nonhepatic Splanchnic NE Spillover

To test whether CGX attenuates splanchnic NE spillover, and to help validate the nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover technique, we compared nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover in a group of CGX and SHAM rats. We expected that CGX, by interrupting the majority of sympathetic outflow to splanchnic organs, would largely eliminate calculated spillover of NE in the splanchnic venous drainage. The value of nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover after CGX was significantly lower (∼78% reduction) than that observed in rats that did not undergo CGX (Fig. 8). Furthermore, our finding that calculated nonhepatic NE spillover was not significantly different from zero in CGX rats (Fig. 8) confirms that the technique is measuring neuronal release of NE and that most nonhepatic splanchnic innervation originates in the CG.

Nonhepatic Splanchnic NE Spillover in DOCA-Salt Hypertension

Consistent with our previous whole body NE spillover data (30, 31), arterial plasma NE concentration (another index of whole body sympathetic activity) was similar in DOCA and SHAM groups throughout the experimental period (Fig. 6A). This again confirms our previous finding that global sympathetic activity is unchanged during hypertension development.

It has been reported that portal venous plasma NE concentrations are twofold or higher than arterial plasma NE concentrations, indicating that splanchnic organs release substantial amounts of NE in the portal vein (1, 2). In the current study, although not consistently statistically significant, there was a tendency for portal venous plasma NE concentrations to be higher than arterial plasma NE concentration. This agrees with previous findings and supports the idea that splanchnic organs are exposed to relatively high SNA under normal circumstances. Nevertheless, the key finding in this part of our study was that nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover was not different in the SHAM and DOCA groups at any time during the study. We conclude that splanchnic SNA is not increased during the development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension.

Fractional extraction is the fraction of NE extracted from plasma during passage through nonhepatic splanchnic organs. Fractional extraction is largely dependent on regional blood flow. An increase in blood flow reduces fractional extraction and vice versa (17). Here we found no difference in fractional extraction between the two groups at any time during the experiment. This suggests that mild DOCA-salt hypertension is not associated with altered NE extraction in the splanchnic organs. There is evidence both for and against alterations in NE removal from the neuroeffector junction in the mesenteric bed of rats with traditional DOCA-salt hypertension (39, 40).

Possible CGX Effects on Splanchnic Vascular Regulation

What accounts for the ability of selective splanchnic denervation via CGX to attenuate hypertension development? Several mechanisms could be responsible, but the most obvious is loss of sympathetically mediated changes in vascular tone. It has been demonstrated that increased vascular resistance in mineralocorticoid hypertension is particularly marked in the splanchnic organs (42, 59). Furthermore, sympathetic regulation of arterial resistance vessels in the splanchnic organs is increased in rats with traditional DOCA-salt hypertension (51). How might sympathetically mediated increased splanchnic vascular resistance occur in light of our evidence that splanchnic SNA is not increased? One possibility is suggested by the finding that mesenteric arterial constrictor responsiveness to NE is increased during the development of traditional DOCA-salt hypertension (55). Enhanced sympathetic neurotransmission to mesenteric arteries also has been found in established DOCA-salt hypertension (48). In the presence of enhanced responsiveness to NE in DOCA-treated animals, even normal levels of splanchnic SNA could produce an increase in splanchnic arterial vasoconstriction.

It has also been demonstrated that rats with established traditional DOCA-salt hypertension have an increase in venous tone mediated in part by the sympathetic nervous system (20, 57). This appears to be caused mainly by increased reactivity of mesenteric veins to released NE (57). Therefore, it is possible that sympathetically mediated venous tone also is increased in mild DOCA-salt hypertension even in the absence of higher absolute levels of splanchnic SNA. Increased venous tone would contribute to hypertension development by causing decreased venous capacitance and translocation of blood from the venous to the arterial side of the circulation.

Several investigators have reported increased release of NE from sympathetic nerve terminals in the mesenteric circulation of traditional DOCA-salt hypertensive rats (11, 48, 56). However, increased NE release should have been detectable with the spillover method but was not found in our studies. Another possibility derives from the fact that there can be a mismatch between NE synthesis and release, sympathetic firing rate and NE release, and rates of NE release and overflow (6, 15, 29, 41). This could result in normal spillover rates in the presence of increased SNA. Therefore, it is possible that nonhepatic splanchnic spillover is unchanged even when sympathetic outflow to the splanchnic bed is increased. Direct recording of splanchnic SNA would be necessary to address this possibility.

Finally, it is possible that NE might not be the primary neurotransmitter involved in sympathetic neurotransmission in the mesenteric arteries of mild DOCA-salt hypertension. Therefore, assays measuring only NE spillover in the plasma would provide insufficient information about important aspects of splanchnic sympathetic activity in the development of hypertension. It has been reported that purinergic transmission is altered in DOCA-salt hypertension (13, 14, 48). Also, there is evidence suggesting the importance of neuropeptide Y (NPY) in neurotransmission in DOCA-salt hypertension (43). Measurement of portal venous NPY and/or purine levels could be used to investigate whether other neurotransmitters play a major role in sympathetic neurotransmission in hypertension development.

Nonvascular Targets of Splanchnic SNA

Splanchnic SNA could also contribute to the development of hypertension by mechanisms other than directly affecting splanchnic blood vessels. Even though retrograde tracer studies of the adrenal medulla have failed to demonstrate any labeling of sympathetic efferent cells within the CG (33), it is possible that some adrenal denervation might have occurred during CGX surgery. Therefore, CGX may have attenuated the release of epinephrine from adrenal gland and caused a reduction in BP. Surgical removal of the adrenal gland during established DOCA-salt hypertension decreased BP (12), and rats that were adrenalectomized and subsequently DOCA-salt treated did not develop hypertension (44). Unpublished data from our laboratory found no changes in circulating NE or epinephrine after CGX in rats, but we cannot rule out the possibility that CGX affected BP by altering adrenal release of catecholamines.

It is also possible that CGX affects water and salt absorption, leading to a decrease in blood volume and BP. We did not measure blood volume in CGX rats, but other studies from our laboratory have not found a consistent effect of CGX on blood volume (35). Salt and water intake measured at the end of the study were found to be similar in both groups. This is consistent with a previous finding showing that extrinsic denervation of small intestine does not alter water and electrolyte absorption (16). This is important because reduced salt intake will attenuate DOCA-salt hypertension development (45, 53), and at least one previous study showed that renal denervation (28) slowed DOCA-salt hypertension development exclusively by decreasing salt and water intake.

Effects of CGX on Visceral Afferents

CGX could alter BP by disrupting visceral sensory afferents. Activation of abdominal visceral afferents has been demonstrated to cause profound cardiovascular responses that include increases in BP, HR, and cardiac contractility (5, 38, 47). Activation of visceral afferents not only increased BP but also caused regional hemodynamic changes in the splanchnic vasculature and a differential increase in the sympathetic outflow to the splanchnic viscera, but not to the heart and somatic tissues (46). Thus, it is possible that BP-lowering effects of CGX in hypertension development could be mediated by disruption of visceral sensory afferent nerves.

In summary, we demonstrated that selective splanchnic sympathectomy using CGX attenuates development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension and conclude that splanchnic SNA contributes to hypertension development. However, hypertension occurred in the absence of increases in splanchnic SNA as measured using nonhepatic splanchnic NE spillover. We conclude that a possible mechanism linking splanchnic SNA and hypertension is increased splanchnic vascular reactivity to NE, leading to increased vascular resistance and capacitance.

GRANTS

These studies were supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant PO1-HL070687. S. S. Kandlikar was supported by an American Heart Association Midwest Affiliate predoctoral fellowship.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert Burnett, Dr. Martin Novotny, and Christopher Riedinger for assistance with the catecholamine assays and Hannah Garver for technical assistance with animal studies.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aneman A, Eisenhofer G, Fandriks L, Friberg P. Hepatomesenteric release and removal of norepinephrine in swine. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 268: R924–R930, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aneman A, Eisenhofer G, Olbe L, Dalenback J, Nitescu P, Fandriks L, Friberg P. Sympathetic discharge to mesenteric organs and the liver. Evidence for substantial mesenteric organ norepinephrine spillover. J Clin Invest 97: 1640–1646, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellinger DL, Felten SY, Lorton D, Felten DL. Origin of noradrenergic innervation of the spleen in rats. Brain Behav Immun 3: 291–311, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bouvier M, de Champlain J. Increased apparent norepinephrine release rate in anesthetized DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Hypertens A 7: 1629–1645, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cervero F. Sensory innervation of the viscera: peripheral basis of visceral pain. Physiol Rev 74: 95–138, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang PC, van der Krogt JA, Vermeij P, van Brummelen P. Norepinephrine removal and release in the forearm of healthy subjects. Hypertension 8: 801–809, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chevendra V, Weaver LC. Distribution of splenic, mesenteric and renal neurons in sympathetic ganglia in rats. J Auton Nerv Syst 33: 47–53, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coker RH, Krishna MG, Lacy DB, Allen EJ, Wasserman DH. Sympathetic drive to liver and nonhepatic splanchnic tissue during heavy exercise. J Appl Physiol 82: 1244–1249, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Boer SF, Slangen JL, van der Gugten J. Adaptation of plasma catecholamine and corticosterone responses to short-term repeated noise stress in rats. Physiol Behav 44: 273–280, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Champlain J, Bouvier M, Drolet G. Abnormal regulation of the sympathoadrenal system in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 65: 1605–1614, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Champlain J, Eid H, Drolet G, Bouvier M, Foucart S. Peripheral neurogenic mechanisms in deoxycorticosterone acetate–salt hypertension in the rat. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 67: 1140–1145, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Champlain J, Van Ameringen MR. Regulation of blood pressure by sympathetic nerve fibers and adrenal medulla in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Circ Res 31: 617–628, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Demel SL, Dong H, Swain GM, Wang X, Kreulen DL, Galligan JJ. Antioxidant treatment restores prejunctional regulation of purinergic transmission in mesenteric arteries of deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. Neuroscience 168: 335–345, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Demel SL, Galligan JJ. Impaired purinergic neurotransmission to mesenteric arteries in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 52: 322–329, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dubocovich ML, Langer SZ. Influence of the frequency of nerve stimulation on the metabolism of 3H-norepinephrine released from the perfused cat spleen: differences observed during and after the period of stimulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 198: 83–101, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duininck TM, Libsch KD, Zyromski NJ, Ueno T, Sarr MG. Small bowel extrinsic denervation does not alter water and electrolyte absorption from the colon in the fasting or early postprandial state. J Gastrointest Surg 7: 347–353, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eisenhofer G. Sympathetic nerve function–assessment by radioisotope dilution analysis. Clin Auton Res 15: 264–283, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Esler M. The sympathetic system and hypertension. Am J Hypertens 13: 99S–105S, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferguson M, Ryan GB, Bell C. Localization of sympathetic and sensory neurons innervating the rat kidney. J Auton Nerv Syst 16: 279–288, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fink GD, Johnson RJ, Galligan JJ. Mechanisms of increased venous smooth muscle tone in desoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Hypertension 35: 464–469, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Funder JW. Aldosterone and mineralocorticoid receptors in the cardiovascular system. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 52: 393–400, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grimson KS, Orgain ES, Anderson B, Broome RA, Longino FH. Results of treatment of patients with hypertension by total thoracic and partial to total lumbar sympathectomy, splanchnicectomy and celiac ganglionectomy. Ann Surg 129: 850–871, 1949 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grimson KS, Orgain ES, Anderson B, D'Angelo GJ. Total thoracic and partial to total lumbar sympathectomy, splanchnicectomy and celiac ganglionectomy for hypertension. Ann Surg 138: 532–547, 1953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hill CE, Hirst GD, Ngu MC, van Helden DF. Sympathetic postganglionic reinnervation of mesenteric arteries and enteric neurones of the ileum of the rat. J Auton Nerv Syst 14: 317–334, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holmes C, Eisenhofer G, Goldstein DS. Improved assay for plasma dihydroxyphenylacetic acid and other catechols using high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl 653: 131–138, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hsieh NK, Liu JC, Chen HI. Localization of sympathetic postganglionic neurons innervating mesenteric artery and vein in rats. J Auton Nerv Syst 80: 1–7, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ipp E, Butler J, Vargas H. Catecholamine concentrations in the hepatic portal system: effect of surgical stress upon portal levels. Diabetes Res 16: 177–180, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jacob F, Clark LA, Guzman PA, Osborn JW. Role of renal nerves in development of hypertension in DOCA-salt model in rats: a telemetric approach. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1519–H1529, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jie K, van Brummelen P, Vermey P, Timmermans PB, van Zwieten PA. Modulation of noradrenaline release by peripheral presynaptic alpha 2-adrenoceptors in humans. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 9: 407–413, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kandlikar S, King AJ, Novotny M, Fink G. Sympathetic activation in the development of DOCA-salt hypertension (Abstract). FASEB J 22: 738.713, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kandlikar SS, Fink GD. Mild DOCA-salt hypertension: sympathetic system and the role of renal nerves. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H1781–H1787, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Keeton TK, Biediger AM. The measurement of norepinephrine clearance and spillover rate into plasma in conscious spontaneously hypertensive rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 338: 350–360, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kesse WK, Parker TL, Coupland RE. The innervation of the adrenal gland. I. The source of pre- and postganglionic nerve fibres to the rat adrenal gland. J Anat 157: 33–41, 1988 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. King AJ, Novotny M, Swain GM, Fink GD. Whole body norepinephrine kinetics in ANG II-salt hypertension in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1262–R1267, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. King AJ, Osborn JW, Fink GD. Splanchnic circulation is a critical neural target in angiotensin II salt hypertension in rats. Hypertension 50: 547–556, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kontak AC, Wang Z, Arbique D, Adams-Huet B, Auchus RJ, Nesbitt SD, Victor RG, Vongpatanasin W. Reversible sympathetic overactivity in hypertensive patients with primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 4756–4761, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li M, Galligan J, Wang D, Fink G. The effects of celiac ganglionectomy on sympathetic innervation to the splanchnic organs in the rat. Auton Neurosci 154: 66–73, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Longhurst JC, Ibarra J. Sympathoadrenal mechanisms in hemodynamic responses to gastric distension in cats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 243: H748–H753, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Longhurst PA, Rice PJ, Taylor DA, Fleming WW. Sensitivity of caudal arteries and the mesenteric vascular bed to norepinephrine in DOCA-salt hypertension. Hypertension 12: 133–142, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Luo M, Hess MC, Fink GD, Olson LK, Rogers J, Kreulen DL, Dai X, Galligan JJ. Differential alterations in sympathetic neurotransmission in mesenteric arteries and veins in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Auton Neurosci 104: 47–57, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Majewski H, Hedler L, Starke K. The noradrenaline rate in the anaesthetized rabbit: facilitation by adrenaline. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 321: 20–27, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. May CN. Differential regional haemodynamic changes during mineralocorticoid hypertension. J Hypertens 24: 1137–1146, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moreau P, de Champlain J, Yamaguchi N. Alterations in circulating levels and cardiovascular tissue content of neuropeptide Y-like immunoreactivity during the development of deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension in the rat. J Hypertens 10: 773–780, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moreau P, Drolet G, Yamaguchi N, de Champlain J. Role of presynaptic beta 2-adrenergic facilitation in the development and maintenance of DOCA-salt hypertension. Am J Hypertens 6: 1016–1024, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O'Donaughy TL, Brooks VL. Deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt rats: hypertension and sympathoexcitation driven by increased NaCl levels. Hypertension 47: 680–685, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pan HL, Deal DD, Xu Z, Chen SR. Differential responses of regional sympathetic activity and blood flow to visceral afferent stimulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280: R1781–R1789, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pan HL, Zeisse ZB, Longhurst JC. Role of summation of afferent input in cardiovascular reflexes from splanchnic nerve stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 270: H849–H856, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Park J, Galligan JJ, Fink GD, Swain GM. Alterations in sympathetic neuroeffector transmission to mesenteric arteries but not veins in DOCA-salt hypertension. Auton Neurosci 152: 11–20, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Provoost AP, De Jong W. Differential development of renal, DOCA-salt, and spontaneous hypertension in the rat after neonatal sympathectomy. Clin Exp Hypertens 1: 177–189, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rowell LB. Importance of scintigraphic measurements of human splanchnic blood volume. J Nucl Med 31: 160–162, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shimamoto H, Iriuchijima J. Hemodynamic characteristics of conscious deoxycorticosterone acetate hypertensive rats. Jpn J Physiol 37: 243–254, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sripairojthikoon W, Wyss JM. Cells of origin of the sympathetic renal innervation in rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 252: F957–F963, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Theriot JA, Passmore JC, Jimenez AE, Fleming JT. Dietary chloride does not correlate with urinary thromboxane in deoxycorticosterone acetate-treated rats. J Lab Clin Med 135: 493–497, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Trudrung P, Furness JB, Pompolo S, Messenger JP. Locations and chemistries of sympathetic nerve cells that project to the gastrointestinal tract and spleen. Arch Histol Cytol 57: 139–150, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tsuda K, Kuchii M, Nishio I, Masuyama Y. Neurotransmitter release, vascular responsiveness and their suppression by Ca-antagonist in perfused mesenteric vasculature of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Hypertens A 8: 259–275, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y. Inhibition of norepinephrine release by presynaptic alpha 2-adrenoceptors in mesenteric vasculature preparations from chronic DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Jpn Heart J 30: 231–239, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xu H, Fink GD, Galligan JJ. Increased sympathetic venoconstriction and reactivity to norepinephrine in mesenteric veins in anesthetized DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H160–H168, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yamamoto J, Yamane Y, Umeda Y, Yoshioka T, Nakai M, Ikeda M. Cardiovascular hemodynamics and vasopressin blockade in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 6: 397–407, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yates MS, Hiley CR. Distribution of cardiac output in different models of hypertension in the conscious rat. Pflugers Arch 379: 219–222, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yoshimoto M, Miki K, Fink GD, King A, Osborn JW. Chronic angiotensin II infusion causes differential responses in regional sympathetic nerve activity in rats. Hypertension 55: 644–651, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]